9. Eric Larson

Animation is a form of communication and therefore when you’re animating you’re making a statement: a statement the character, the story, the feelings and emotions the character is feeling, human characteristics and emotions, actions, personalities, archetypes, etc. If you want to have the audience get involved in the story, connect with the character, and feel the emotions needed to sympathize and relate to that character you must make a positive statement. To make a positive statement you have to know your character and their personality, have a devotion to your craft, know how to use your art to express the statement you want to make, apply feelings and emotions that are strong and real to a fantasy story, and most of all have sincerity. If you don’t have feelings and emotions for your character, how can it even be possible for the audience to? Few people have ever understood sincerity and making a positive statement better than Eric Larson, number 9 on our countdown and the subject of today’s post.

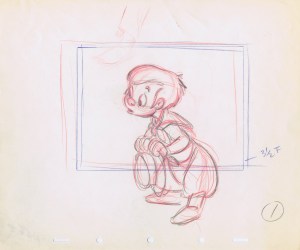

Eric Larson was a terrific animator who had the great ability of having sincerity about his work and making characters believable and have them feel real on the screen. He truly cared for his characters and had a gift for taking something that people are familiar with as well as an emotion and personality they’ve seen or experienced and utilizing those two things to make the audience fall in love with a character. “”Make a positive statement,” stressed Larson. “Don’t be ambiguous in what you’re saying. Make it strong and clear.” He was an expert at animating believable animals such as Figaro the cat in Pinocchio, the Pegasuses in Fantasia, Friend Owl in Bambi, Sasha the bird in Make Mine Music, Peg in Lady and the Tramp, and the vultures in the Jungle Book but his best work includes humans such as Cinderella and the boy and girl in the Once Upon a Wintertime sequence in Melody Time. “Eric really cared for characters as human beings,” remembered excellent character designer Dan Haskett. “I was doing a pencil test of a baby boy and he started pantomiming patting the little kid on the head and got lost in what he was doing because he was thinking about the character so completely.” “Eric was very, very gentle and he knew timing like nobody’s business,” said animator and dancer Betsy Baytos. In real life Eric was a very giving, gentle, and unselfish human being who always helped mentor others and for decades was largely responsible for keeping together the sometimes egocentric and hyper aggressive top animators at the studio. He had no ego and people always felt comfortable asking him for advice and guidance. Larson for the last 16 years of his career worked pretty much exclusively on running the training program at the Disney studio and was very successful at finding talent (honorees Mark Henn, Andreas Deja, Duncan Marjoribanks, Ruben Aquino, Dave Pruiksma, Tony deRosa, Will Finn, Ellen Woodbury, Dale Baer, John Pomeroy, and Kathy Zielinski all either went through Larson’s training program or were hired during his time as head of the training program.) However there was a drawback to his nature because many of the other directing animators as well as at times studio management pushed him around and as a result of his unselfishness and reserved personality he hasn’t always been appreciated as much as he should be.

Eric Larson was born on September 3, 1905 in Cleveland, Utah but moved to Salt Lake City around age 10. He was born into a Mormon family and would continue to be devout and active in the faith all through his life although he didn’t talk much about his beliefs at the studio. Larson grew up on a ranch and became fascinated by the animals that live there and their personalities. “I was born and raised on a ranch,” he remembered in an interview. “And I always wanted to be a rancher up to the time of my second year in college. It’s still a life I love, would still like to do.” Other things that particularly intrigued Eric were writing and drawing (the later he started doing around the age of 10.) Although he never took cartooning very seriously until he got to the Disney Studio at age 27 throughout high school at Latter Day Saints University he drew for the school yearbook and was the art director of it in his final year there. On the side Eric sold illustrations to Westerner Magazine. Soon he entered the University of Utah where he studied journalism and wrote for the university paper the Chronicle as well as studied drawing on his own private time and he drew cartoons for the university humor magazine. In spring 1927 a personal incident that he never mentioned to his colleagues at Disney (in respect to Eric’s wishes I’m not going to repeat the story here but you can read about it in John Canemaker’s book) took place that made the young man leave the university as well as Salt Lake City forever. “My whole attitude and whole hope after getting out of school was to just write and travel,” he remembered. Larson then moved on to work as a commercial artist in Los Angeles for 6 years. While working there through a window he saw a beautiful woman named Gertrude Jannes and immediately told the person sitting next to him that’s the girl he was going to marry. Eric and Gertrude quickly fell in love and the prophecy was fulfilled when the wed in 1933. Now married he wanted to find a job with higher dignity and pay so he decided to pursue a career writing in radio. Larson was sent to get advice from former radio writer Richard Creedon, who then was working in the story department at the Disney studio. Creedon liked his work but said that in the meantime he should get a job working at Disney. At first Eric was reluctant but after the writer told him “The animated film will challenge any creative ability you have or will develop,” he was intrigued and started as in inbetweener in 1933.

At first Eric Larson wasn’t too happy at Disney and almost quit early on in the first few days largely because of George Drake, a man with no talent who was in charge with the inbetween bullpen only because he was married to Ben Sharpesteen’s cousin. “Drake would sit down and make a correction for you but he couldn’t draw worth a damn,” the animator remembered. However Eric stayed with it and after 5 weeks as an inbetweener the great Ham Luske discovered his talents and through request made him his assistant. As I explained in my post ton him Luske was an intense analyzer who constantly studied life and action as well as applied this knowledge to his work. Finally Larson had found someone who could enlighten him to the great possibilities of animation and mentor him to make his talents shine. “Ham had to work like dickens to draw,” he explains. “Freddy Moore just wrote it off but Ham had to work his fool head off to make a drawing. Every action had to be honest and to have character and sincerity.” Ham’s thoughts on sincerity would influence Eric’s approach and thoughts on animation forever. Also he became the first assistant animator to be in charge of the cleanup of the main animator he was assisting. “I moved in with Ham and first word I got was now the assistants were going to be responsible for all the cleanup work,” Eric said in an interview. “I wasn’t too sure what a cleanup drawing should be! Ham was very patient and he helped.” After a year working as his mentor’s top assistant the animator started to animate his own scenes but even still he worked primarily for Luske. He started animating on shorts such as animating the chorus girls in Cock O’Walk, a Silly Symphony released in 1935(It also was the great Bill Tytla’s breakthrough film.) One of Larson’s first major assignments as a full-fledged animator was being assigned in the unit of animators that would animate the animals in Snow White. Ham supervised the unit (although he only actually animated Snow White herself) and the group included such promising young artists as James Algar, who would go on to direct the Sorcerer’s Apprentice segment in Fantasia as well as sequences in Bambi, and Milt Kahl, who would go on to become one of the greatest animators of all time. “When we started working in features we started to spend more time on personality because Walt knew we needed strong personalities for the features to work,” explained the animator. On many of the scenes especially the ones he animated with the animals walking around Snow White and the ones of them cleaning up in Whistle While You Work Eric animated all the animals on separate sheets of paper to concentrate on them separately. He also used thumbnail sketches for every 2 feet of animation to help feel the composition. In later years Eric grew very critical about the animation he did of the animals and resented the way they turned out. “You could hardly call them deer,” he unhappily stated. “They were stacks of wheat. When we got to Bambi, the idea was to be honest with them.” It was however the next feature film that would prove to be the film where Larson became a star. The film was Pinocchio and the character was Figaro the cat.

“Pinocchio today would be impossible to make,” Eric Larson told Steve Hulett. “They wouldn’t spend the amount of money that would be necessary. We just wouldn’t do it now. Where in the world would you ever get the underwater effects? Where in the world would you get the ocean effect, the water effect when Pinocchio and Gepetto were on the raft, escaping from the whale?” In many ways Figaro is his signature performance because it displays all of what he did best: giving animals believable human personalities, combining caricature and fantasy with believable movements and real feelings, using walks and poses to show character, brilliant timing, inspiration, action analysis, and last but not least sincerity. For the inspiration Eric used his nephew, who influenced the cat’s personality and antics. “A 4 year old kid is quick to feel hurt if he doesn’t get what he wants,” he explained. “He is probably going to put on a show for us, a tantrum. Take an animal, like Figaro, move him around as a kitten would move. You don’t take any liberties with that kind of acting but now you inject into him a personality of this young kid who is used to having everything he wanted. This is where we would cross from realism to fantasy, in my opinion.” Larson’s animation of Figaro is brilliant because like he explain he’s completely believable as a cat and has the movements of a cat but has expressions and feelings that are very human. The animator did a brilliant job at using pantomime and expression through the entire body to make the cat’s personality and emotions resonate well with the movement. Not only is the timing brilliant but there is a great combination of having Figaro realistic enough to be believable but caricatured enough to make him fit into the story and have the audience accept his human expressions. Last is there is a great honesty and sincerity in Eric’s animation of the cat. It is so apparent that he cared very much about his character and craft making the audience believe in him more. There are two Figaro scenes that are must-studies: the one where he gets out of bed and closes the window (pantomime and combining realism with caricature as well as timing at its best) and the one where he pouts about having to wait to eat his dinner (great use of clear poses and showing character.) Larson had now proven himself a top animator at the Disney studio and would continue to do great work but perhaps the intimacy between animator and character was never as present in his other work as it is in Figaro.

After Pinocchio was completed Eric Larson was moved on to be a directing animator on the Pastoral Symphony sequence in Fantasia alongside such household names as Ward Kimball, Fred Moore, Ollie Johnston, and Art Babbitt (his mentor Ham Luske directed the segment.) His Fantasia work would bring one of his biggest successes in his career but also would bring one of his strongest resentments and failures. On the high note it had his absolutely beautiful animation of the Peaguses flying. The flying horses move gracefully, are expertly timed to the music, and have the great essence of a horse moving as well as the balanced flying motion. On the flip side Eric’s animation of the centaurs in the segment (he primarily did them in the scene where they’re carrying the baskets while Fred Moore did a lot of them in the part where they fall in love with the centaurettes) was grotesque and clumsy in a way no other Larson scene is. This bothered him for decades and he was still honestly upset when talking to trainees about it in 1980. ‘They were lousy to animate because their design was completely wrong,” Eric sighed to his students. “We didn’t analyze the live action sufficiently to get a horse action in there. If you watch the front legs of these centaurs they have a certain human feeling and it shouldn’t have been that way. If I had just thought about it then it would be so much better.” Eric and Ollie Johnston moved onto Bambi in spring 1940 after completing their work on Fantasia joining Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl as the four supervising animators on the film. However although he wasn’t on the crew the animator did do friend Ben Sharpesteen a favor by without screen credit animating the animals cuddling together in the Baby Mine sequence of Dumbo, where he did all the animals except for Tytla’s Dumbo and Mrs. Jumbo. On Bambi Larson supervised a large crew of over 30 people including 10 animators such as Don Lusk (a great underrated Disney animator known for his specialty in animals and strong draftsmanship who did some stunning, magnificent animation on the Great Stag on the feature) and Retta Scott (the first female animator at Disney who animated the hunting dogs in the film.) “On Bambi he had the largest crew of any of the top men and there was always someone in his room with a problem, often nothing to do with the production,” wrote Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. “Eric was always patiently listening, occasionally counseling, but somehow he was still one of the best footage men in the studio. And to top it all, he was able to get footage out of most of his crew.” As for his actual animation on the film Bambi was casted by sequence but Eric primarily worked on doing most of the scenes with the outspoken and sometimes paranoid but always intellectual Friend Owl, which allowed him to work more broadly and he did a brilliant job at getting into the character as well as applying that personality to the action and performance, and the reserved but majestic Great Stag, a very difficult assignment and probably the subtlest character the animator did in his career. My favorite scene he animated on the film is the one where the owl is talking to adult Bambi, Thumper, and Flower about being Twitterpatted and is doing all the actions and poses displaying how that is like. It’s a good example of showing how emotion affects character: owl, who usually is pretty calm and well spoken in manner, is becoming crazy and all over the place because he’s feeling inside him his attitudes and opinions towards what he sees with people falling in love. On top of that the actions supporting the feeling and dialogue is spectacular.

During World War 2 Eric Larson stayed at the Disney studio and spent most of his time doing some very subtle and warm animation of the boy in the Flying Gauchico segment of the Three Caballeros but he’d continue to shine on the package features animated in the second half of the 1940s. On Make Mine Music he animated Sasha the bird in the Peter and the Wolf segment, which was a very warm, believable performance displaying great usage of timing to music and looseness in movement to show expression and feeling. “I had the musicians put down on the exposure sheets each and every note that involved Sasha,” explained Larson. That same year Song of the South was released, which in the animated segments showed some of the best character acting that he ever did for the studio. Although he animated all three characters Eric’s animation for Brer Bear has always been a favorite of mine because the performance he did is so true to the character and the personality Bill Peet had planned through the storyboards. He clearly communicates through his actions, gestures, and walks that the bear is indeed an idiot who doesn’t think to hard about anything, is dumb, and just wants to get it over with. To show this Larson made his walk very uncoordinated and showing tremendous weight while making his gestures and poses very unpolished and having the expressions show he isn’t thinking that hard. The next film, Make Mine Music, would also turn out to be a tremendous triumph for Eric where he animated some very sincere, subtle, and warm animation of a young boy and girl couple in love in the romantic Once Upon a Wintertime segment as well as the crazy bird in the Samba segment. In the Wintertime segment he did an excellent job at staying true to the beautiful, stylized Mary Blair designs and sketches while adding to them a three dimensional quality and roundness that makes them seem believable and real (hard to do with a Blair drawing!) I love the understanding of emotions and relationships he shows as well as the subtle expressions and gestures that are held back but communicate so effectively. The bird, on the other hand, is unique in that he is by far the broadest character Larson ever animated and has a wackiness and cartooniness that would be expected in a Ward Kimball or John Sibley scene but is completely unconventional for Eric. However on the next film the animator’s hard work and effort was completely ignored because he was given no screen credit for his work on Ichabod and Mr. Toda, where he animated a lot of great scenes in the Wind and the Willows section. Don Lusk was credited for all of his scenes after work resumed on the project (Larson started working on it immediately after Bambi but it was shelved due to budget cuts.) He was very hurt because he felt he did a lot of his best work on the film, including crediting the part where ratty says he misjudged Toad as the best dialogue he ever did. “I guess Toad was one of my favorites,” stated Eric in a television interview. “I think some of the most enjoyable actions I was ever able to get on the screen was Toad’s defense of himself in court. I felt that I did get a tone that is the peak of arrogance in that figure of action.

As disappointing as it must have been to go no credit for his work on Toad Eric Larson was indeed given credit for his work on the next assignment, which was a much more important one and arguably his best work. The film was Cinderella and Eric had the challenge of being the first animator on the film and having to bring the charming, sweet heroine to life for everyone to fall in love with. This was the first cohesive story Disney had done since Bambi and the success of this picture was vital to having a successful future for the studio. Cinderella was a challenge for several reasons. While in Snow White the love and affection the dwarfs and the animals as well as the jealousy of the queen were able to tell a lot of the story and take a lot of emotional weight Cindy had to take a large amount of the weight in the story because she had to connect so many plots to each other: the Stepmother, the conflict between Lucifer and the Mice, and the King, Duke, and Prince plot. She also had to be very sweet and have a homely feel but she had to have an intelligence and strength to be able to stand up for herself and make her dreams come true so she couldn’t be too passive but had to stay warm-hearted and believe in herself. The last main challenge was that Cinderella as a film, with the exception of the animals, was all shot in live action so the animators had to be able to use it as a resource to make the action realistic and believable but it had to be caricatured and creative to avoid making it too realistic and having it remain appealing. While Eric animated Cinderella first and animated the majority of the footage Marc Davis came on a little later and the two didn’t necessarily see eye to eye on the character (a little bit of a reflection and taste of the much more hostile and intense conflict between their mentors Ham Luske and Grim Natwick over Snow White.) While Larson wanted a girl who was very warm, soft-spoken, comforting, and sweet and saw her as a sixteen year old girl with a pug nose Davis saw her as a bit older, more sexually aware, witty, intelligent, less passive, and what the other called “a more exotic dam with a swan neck as only Marc Davis could draw.” In many ways unlike the earlier conflict the two men actually used their two interpretations of the character in a way that actually benefited the story and the result was the most interesting and possibly the most dynamic Disney heroine ever: Cindy is warm and sincere but also is intelligent and has emotional strength. However it was the heart and soul that mattered the most as well as the sincerity so ultimately you could saw Eric’s girl is ultimately the one that won the battle and the one girls all over the world of all ages have fallen in love with for decades. Although Marc’s Cinderella is more tied down fortunately the drawings were made to work together thanks to an unsung hero. “Ken O’Brien was able to make Marc’s gals look like my gals,” stated Larson. O’Brien is an underappreciated animator who was brilliant at subtle movements and especially at animating females (then he was still just a cleanup artist.) Personally Eric’s animation of Cinderella is very inspirational to me and I credit his work on the film as one of my prime motivators into deciding to pursue Disney animation as a career. I love how delicate and sincere she is! Larson did a great job at making her movements timed very evenly and using subtle delicate gestures and expressions to communicate her feelings and desires. One scene I particularly love is the one where she is waking up in the morning and talking about how wonderful a dream she had. This one really shows the sensitivity Eric had in full tact as well as a textbook example of warm, sincere animation in a character. He also animated Cinderella in the scene where she’s looking out the window and her dancing with the prince at the ball, to name a few. Larson also was the lead animator on the prince on the film (a character that has mistakenly been credited by many people as being animated by Milt Kahl although he didn’t even do a single scene of him or Cindy.) “The nice thing about Cinderella is that you know what she is thinking in every scene.” the animator simply stated to Andreas Deja.

While Alice in Wonderland was as much of a triumph for Eric Larson as Cinderella it still contains a lot of good work from him. His main focus on the film was animating the stubborn, rude Caterpillar, which proved to be a good challenge because it was very hard for him to look appealing. Eric had a hard time being cartoony and broad with the character the way the film was supposed to be, although several animators on the film with the major exception of Ward Kimball failed to be able to contribute to the goal of making Alice a cartoony feature (it wouldn’t be until Aladdin 41 years later that Disney proved they could do one.) also on the film the animator animated some of Alice, particularly in the scenes before she goes into Wonderland and she’s singing In a World of My Own. Larson’s Alice isn’t as tied down as Marc and Milt’s were but she is very subtle and has sincerity in her performance. Last on the film he animated the Queen of Hearts when we first see her where she is yelling and demanding to know who painted the roses red. I think Eric’s Queen is appealing and has solid acting but I think it wasn’t necessarily good casting and Frank Thomas certainly gave her a psychological precision and craftiness that was needed for the character that just wasn’t in the other gentleman. On Peter Pan the animator had a very challenging assignment: he had to animate the sequence where Peter and the kids fly into Neverland. This required Larson to have to use an expert knowledge and utilization of mechanics as well as focus more on technique than is usually done in his scenes. However, there still is a great spirit and feeling to the animation that only he could add. “We not only used multiplane, we had to work the hell out of that camera-per-fields and in-and-out exaggerations, going away from you and coming at you,” explained Eric. “Besides drawing that we put emphasis on it by using camera tilts. It was a very beautifully worked out thing mechanically. It really has a certain thrill to it.” Up next for the animator was a really juicy assignment that he thoroughly enjoyed and in my opinion is alongside Cinderella and Figaro as his best work. It was animating all of Peg, the sexy female dog who is a free spirit and has a strong affection for Tramp, in Lady and the Tramp. Only Ollie Johnston’s girl in Reason to Emotion is the only Disney character anywhere close to being as sexy as Peg. Larson did a brilliant job at using touches in the way she walks and moves to enrich that personality and the acting is top notch. In particular a huge inspiration to him on the character was Peggy Lee herself, who voiced the character. “The way she sang the song was a great inspiration,” he remembered. “Also the way she walked because she had a pretty nice movement and these are thing that you try to pick up from human beings and translate into animals.” True to what he explained I’ve got to admit I’m a real sucker for the walk he gave the dog: that alone is enough to tell the audience she’s seductive and is a free spirit due to the tone of the walk and the spacing between the steps. The design is something I love too. “It was interesting because here was Eric, who’s a Mormon, and he’s animating this sexy girl and having the best time,” chuckled Burny Mattinson.

Sadly however the next film he worked on proved to be a very negative experience for him and turned the direction of his career in a negative way that he was never able to overcome. The film was on Sleeping Beauty but this time he was in the director’s chair. Sleeping Beauty had begun story work in 1951 and voices were recorded soon after but in December 1953 Wilfred Jackson, who up to that point was directing the project, had a heart attack and had to step down. It is unsure why Eric was the one they picked but likely it’s because of his success supervising units of animators. However the production proved to be extremely difficult and things moved extremely slowly. “Eric got his first sequence to work on in Sleeping Beauty and had very little help,” remembers Burny Mattinson, who would later assist Larson for a dozen years. “Even his longtime assistant George Goepper was modeling things for Disneyland. So everything moved very, very slowly. Eric was also one of those very precise people so when he handed out sweatbox notes, he told you exactly how to correct the situation. The notes were very long and detailed. I think management looked at those notes and though, this guy’s making too much work for these people. It was wrong that he got a lot of blame for it.” Although he was good at paying attention to detail and was always very patient, he ultimately didn’t have the guts and leadership to put everything together and keep the production moving. Larson also wasn’t very good at being a hammer and didn’t do much to prevent tensions and problems on the production, such as Eyvind Earle’s over dominance of the film. He also got a lot of blame for the large budget of the film. Sadly in 1958 Eric was removed as director of Sleeping Beauty and Wolfgang Reitherman and Gerry Geromini finished the picture. After Sleeping Beauty the animator only got to be a directing animator one more time, which was on One Hundred and One Dalmatians were he animated a lot on the puppies. Larson’s most notable scene on the film is the one where all the Dalmatians are watching TV, which has some beautiful personality animation and great warmth. Unfortunately however things were getting a lot more cliché at Disney and with Wolfgang Reitherman as the director of the films it was quite easy for a unselfish, laid back animator like Eric Larson to go underappreciated and pushed around. As a result on Sword in the Stone he was demoted to character animation and only animated a few bits and pieces on the film. On Mary Poppins he animated the farm animals and did some very good stuff on them. The demotion was still held during Jungle Book but he did get more scenes that in Stone by quite a bit including Mowgli arguing with Bagheera and a lot of stuff on the vultures. His vultures show the animator’s extensive knowledge of animal anatomy and strength in the fundamental of timing in animation. On Aristocats he was continued to be phased out and did some animation of Scat Cat as well as a lot of the mouse. His last feature was Robin Hood, were he animated only a few scenes of Little John and was gradually phased out during the production. So in 1973 Eric put down the pencil and decided to spend all his time on his more important endeavor, his job as the head of the Disney training program.

While many animators and artists at Disney didn’t care too much about the future of Disney animation, were focused on battling with each other and extending their careers, and were at best passive to the issue that they hadn’t done a good job of training new artists and finding a continuous flow of talent to the studio. With the Disney films not in as high quality as they used to be and artists beginning to get old, retire, and in some cases even die Eric Larson, who was one of the few very concerned about passing on the legacy of Disney and the future of the studio, sacrificed his career so he could devote full time to training a new generation of artists. “Eric loved to teach because he loved young people,” fondly reflected Andreas Deja. “He was someone you’d want to have as a grandfather.” Eric’s training program was essential in setting the foundation for the second generation to shine and found such talents as Ted Kierscey (1970), Dale Baer (1971), John Pomeroy, Ron Clements, Andy Gaskill (1973), Glen Keane (1974), Ed Gombert, Randy Cartwright, Dan Hansen (1975), John Musker (1977), Brad Bird, Jerry Rees, Mike Giamo, Chris Buck, Mike Cedeno (1978), John Lasseter, Hendel Butoy (1979), Andreas Deja, Mark Henn, Barry Temple, Joe Ranft (1980), Kathy Zielinski, Dave Pruiksma (1981), Ruben Aquino(1982), Ellen Woodbury, and Duncan Marjoribanks(1985). However in that time frame he had some bad experiences. First of all his beloved wife Gertrude passed away in 1975, which made him very depressed. One infamous one is being removed as the director of The Small One. Larson had intended for this to be a film where the young guys could shine and learn as well as learn from him and such veterans as Mel Shaw, Vance Gerry, and Cliff Nordberg. However as Burny Mattinson explains, “So we came in on Friday, everything was happy. Monday, everything in our rooms was gone. Everything! Every storyboard, every drawing we had on it. The rooms were wiped out. We found out that management had over night decided to turn over the project to Don Bluth to direct. It was a horrible thing to do. It originated with Eric. It was for Eric’s use and then these guys just moved in. Eric stayed teaching but things were never the same.” Many people blame Bluth taking over the Small One as the event that broke the piece at the Disney studio and began all the politics and battles that would extend well after Don Bluth departed in 1979. Whosever side you were on the family, college campus feel to the studio was over and Eric, who wasn’t happy at all with the politics, had to constantly tell people to concentrate on the art. However 7 years later he again had hard feelings towards management when the takeover took place and he was forced off the Disney lot alongside the rest of the animation staff to a warehouse in Glendale. Larson wasn’t at all happy with the new management and after the move felt very depressed in his enclosed office with no windows contrasting his sunny, nice office he had worked in for 40 years. At the age of 80 he retired in 1986 although he went into a deep depression after and felt very homesick for Disney. On October 25, 1988 Eric Larson passed away at the age of 83. The prince in the Little Mermaid was named Eric in his memory.

Style wise Eric Larson’s greatest asset as an animator was without question his great sincerity that was to an extent that is almost never found in people. Although he wasn’t a flashy or phenomenal draftsman there is a warmth touch and great amount of personality and understanding of character in his work that is heart warming and beautiful. You love these characters because Eric was so submerged and focused on the character in a way almost no other animator has ever been. When you see his stuff up on the screen it feels very intuitive and the character is always very rich and complete. To understand his characters and figure out his animation Larson would not only act out the scenes but he would imagine the scene in his head. Everything he drew and animated he first saw in his head. After imagining the scene he would analyze and think very thoroughly about the character and their feelings and personality. In terms of design Eric’s stuff is very round and appealing looking with more curved, sparse lines than an animator such as Marc Davis or Milt Kahl. His designs were always in the Disney style but were more conventional and not very stylized. As I mentioned before Larson was particularly gifted at timing and worked his scenes out on diagrams and exposure sheets and timed it out expertly before actually animating it. Assisting him was rather easy because he animated relatively evenly. Eric’s scenes are on fours instead of twos, giving and organic, even feel to the movement and lacking the complicated, sometimes overdone technical animation of some other people. “There’s only two things that limit animation,” the animator explained. “One is the ability to imagine and the other is the ability to draw what you imagine. The basic thing that animation has to have is a change of shape. When you change the perspective of the shape, the charm of animation is how you time that after you’ve gotten all the character into pose drawings. That’s weight to be concerned with. We don’t take steps, we fall into them. You take what you know is real and honest and you exaggerate it, you caricature it for all it’s worth. Then you begin to get the humor, whether it’s an action, expression whatever. The interpretation the animator gives as an action will depend on the quality of the animator. If we can’t relate to the audience, we might as well give up. This is what Walt wanted.”

Without question the influence Eric Larson has had on Disney animation is immense and is still very influential today. As an animator his warm, believable work and intimacy between animator and character is something anyone should be inspired to do that’s in the field. Eric’s work has a very sincere quality and it is very true to what the heart of Disney animation is about. When he was animating he was a great inspiration in that he helped keep the animators together and was vital to mentoring younger guys as well as counseling and helping solve problems always in a patient, gentle way. Larson deserves a lot of credit for his excellent performances in the Disney films and it is sad to be that oftentimes his contributions are ignored. For example I’m shocked at how rarely it is mentioned that he was the main animator on Cinderella! His animation on her is some of the best stuff ever done with a Disney heroine but no one even acknowledges that he was the key to her. As for his inspiration as a mentor and impact on preserving the Disney legacy it is indescribable the impact and influence he has had on the second generation. You could even say quality Disney animation could very well have died if it weren’t for the passionate, talented artists Eric mentored and nurtured to their highest potential.

Eric Larson is one of my biggest inspirations and heroes not just in the realms of animation but also in life. His sincerity, love for his work, and sweet, gentle nature is something I want to emulate and strive to stay true to everyday of my life. In terms of animation his richness and indulgence into the character and expert use of timing is inspirational to me in a very strong way. Larson is for the lack of a better word an idol to me: I look up to him and want to emulate him both as an artist and as a man. I will always remember this great quote the animator said: “All an artist has is sincerity.” Perhaps no single quote has spoken to me in such a way as this one. It reminds me that we need to set down out egos and instead give animation our fully heart, passion, and take out the best in us to do the best possible work we can. Thank you Eric Larson for your contributions to the art of Disney animation and its legacy as well as for being a great hero and inspiration to me as well as so many other people!

![snapshot_dvd_00.45.59_[2011.04.30_14.43.05]](https://50mostinfluentialdisneyanimators.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/snapshot_dvd_00-45-59_2011-04-30_14-43-05.jpg?w=300&h=240)

October 21, 2011 at 2:37 am

Love this information. Can I use the picture of Eric Larson on my blog. I’m doing a post on him because he was born in Emery County, Utah. If not, I will erase it. I’m not sure about such things.

October 21, 2011 at 2:39 am

I also quoted you in my blog and put a link to your site. Please advise me if I’m in error.

October 21, 2011 at 3:09 am

Absolutely. Thanks, actually, for writing about Ericl May I see the post?

April 12, 2012 at 12:22 am

I’ve got a question about Eric–yes, we share the same first name & all that, but here’s what I’d like to know: Even though Wilfred Jackson had a heart attack & had to step down from directing, why did Walt ask Eric to help direct sequences in Sleeping Beauty if he hated directing? If I were Walt, I’d have kept him where he was, especially since he just did what you say was a “Very juicy assignment which he thoroughly enjoyed” in Lady and the Tramp! Well, at least he went back to animation in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, but why did Walt ask him to direct?

April 16, 2012 at 10:47 pm

Hello there! I found this article really, really interesting. Thank you so much for posting it. Eric Larson is actually my great-great uncle and I’m really interested in learning more about him. I was wondering if you could tell me which of John Canemaker’s books you mentioned and the other books where you got all this information. Thank you!

June 28, 2012 at 11:27 pm

Where can I find the animation drafts for the Disney films? I’d like to actually take a look at their work ’cause this is all very interesting! If you don’t mind!

June 29, 2012 at 1:42 am

Not all of them are available on line but here is a site that has a ton of them http://graysonpontianimation.com/2012/06/29/44-the-trialichabod-and-mr-toad/

July 25, 2012 at 6:04 am

Thank you for such an extensive work on Eric. He is my grandfather’s brother, and I was always very fond of him. Your article is definitely a new found treasure to add to my memories.

December 20, 2013 at 3:29 pm

Pedro Berruguete’s portrait of the duke perhaps best sums

up his character: Bedecked in shimmering armor and silk robes, the duke sits

reading serenely, his small son, Guidobaldo, at his knee.

Small things like that really make all the difference.

If you are a guy and your girlfriend has just

broken up with you, there is no doubt that you will be going through a pretty rough time right now.

December 24, 2013 at 1:41 am

I too am related to Eric Larson this article was amazing! Thank you for the wonderful well written information. I never got the pleasure of meeting Eric but he was a very important part of my life. His brother was one of the most important people in my life.

July 17, 2014 at 1:36 am

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your weblog.

Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself?

Anyway keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a

great blog like this one today.