HR Giger Necronomicon is not as shocking anymore today. Satanistic inspirations, deformed bodies, the free union of eroticism and decay – if the pop-culture mainstream did not numb us to it, its sub-genres definitely have: from the metal subculture, through cyberpunk, ending at body horror. However, we likely would not have accepted ugliness as a means of expression to the same degree if not for the artists who had been crossing the boundaries for years – like the author of the famous album Necronomicon, the creator of the Xenomorph, and one of the most influential surrealists of the turn of the century.

Many artists mention their childhood as a source of inspiration, though few have reached as deep into their subconscious as Hans Ruedi Giger did. He was born on February 5, 1940 in the Swiss city of Chur. The painter stated that the experience which had had a powerful effect on him was the trauma of his own difficult birth. Regardless of whether this is psychologically possible, it cannot be dismissed that physicality (and even, in Giger’s perspective, mechanicality) of pregnancy and birth was a crucial theme in his work. H.R. Giger Necronomicon and all of his work are sometimes interpreted as therapeutic in a way – a means of dealing with both individual and collective fears; Giger’s first paintings were created during art therapy sessions, after all. The artist’s most widely known creation, the design of the Xenomorph from the movie Alien, is not unlike a lens, focusing a host of primal fears, such as those connected with parasites. Ridley Scott’s beast may have looked completely different if not for H.R. Giger’s earlier achievement – an album with a telling title, Necronomicon.

Lovecraft, Crowley, and Jesus

Dan O’Bannon, the co-creator of the script for Alien, met H.R. Giger while working on the movie adaptation of Dune directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky. The film never came out, but O’Bannon’s and Giger’s acquaintance continued. Impressed by H.R. Giger Necronomicon, O’Bannon suggested that Scott bring Giger to work on their sci-fi horror film. One of the reproductions in the 1977 album would go on to become the Xenomorph.

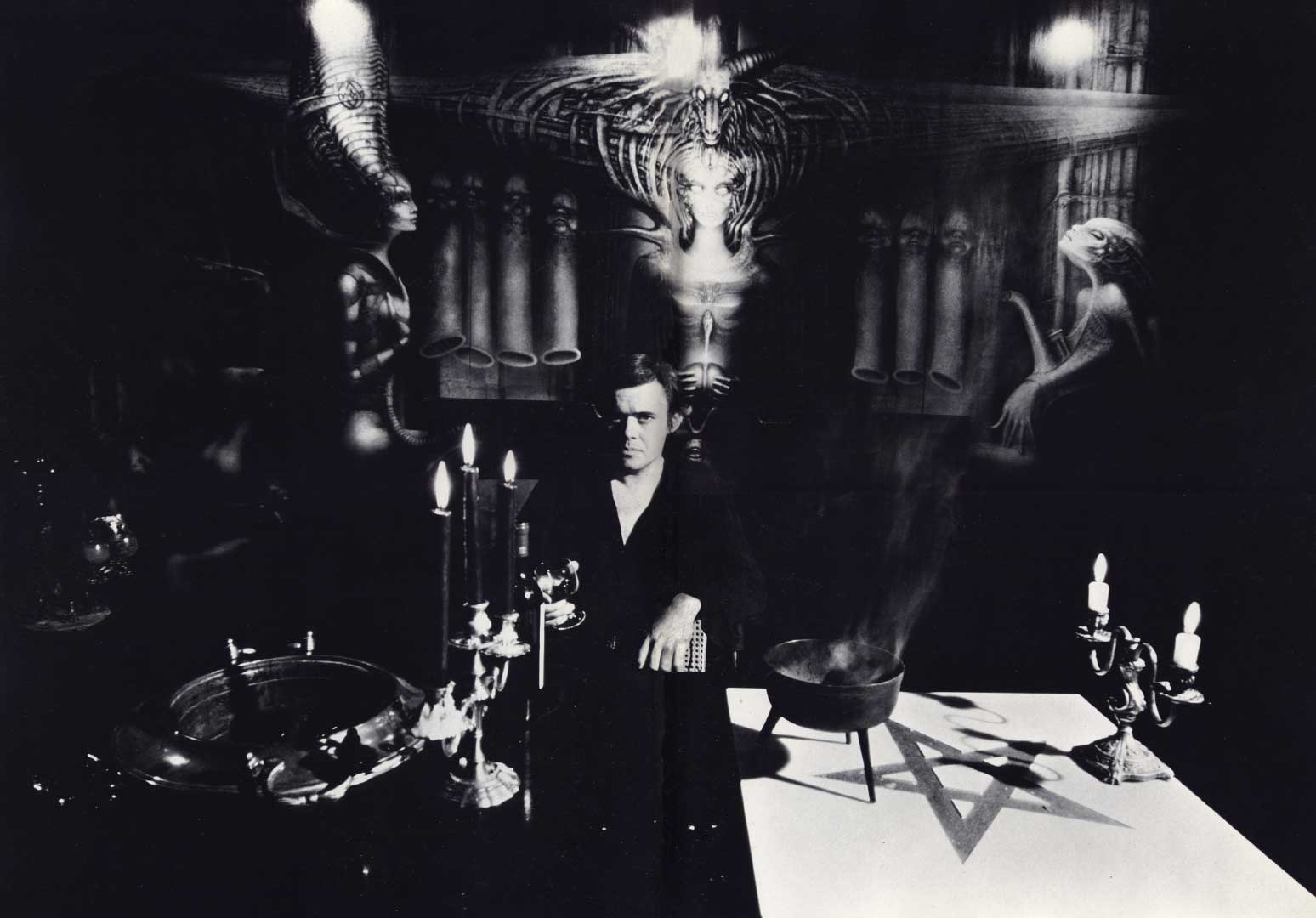

What is H.R. Giger Necronomicon? It could be called the opposite of a coffee table book: an elegant form and the focus on the visual contents seems to place H.R Giger’s book in that particular publishing niche, but the unnerving exploration of the deepest, darkest fantasies says otherwise. The album cover scares the viewer with the image of Baphomet, a goatlike demon who had allegedly been worshipped by the Templars. The title itself is significant, as it was not coined by H.R Giger himself. The name Necronomicon comes from H.P. Lovecraft’s writing in which an early-medieval grimoire of the same name can be found; it is a madness-inducing culture book full of forbidden knowledge – as an aside, Lovecraft had to explain that he had invented the tome on numerous occasions. Lovecraft was recommended to Giger by his friend, Sergius Golowin – a librarian, occultism aficionado, and Timothy Leary’s companion during his Swiss “exile”. These circumstances clearly show the intellectual and social atmosphere surrounding the creation of H.R. Giger’s himself.

Contrary to the title and the book cover, references to the occult do not dominate the contents of Necronomicon. There are more pictures of Baphomet and short mentions of Eliphas Lévi, Aleister Crowley, or tarot, though esotericism appears to exclusively serve as the background to the artistic obsession of corporeality – both sexual as well as suffering. In a later book, ARh+, H.R. Giger mentioned that the source of his interest in the macabre was Jesus’ bleeding head he had observed in catholic kindergarten. The complicated relationship of Christianity and corporeality is also the theme of the works in H.R. Giger Necronomicon – including Satan I, a painting depicting the titular Satan using the arms of the crucified Christ as a slingshot. Christian themes in H.R. Giger’s art point towards an interesting idea: everyone brought up in the Christian culture is used to depictions of a dying man, and one of the most important symbols of the western civilisation, the cross, is, in fact, a torture device.

Body as a Machine

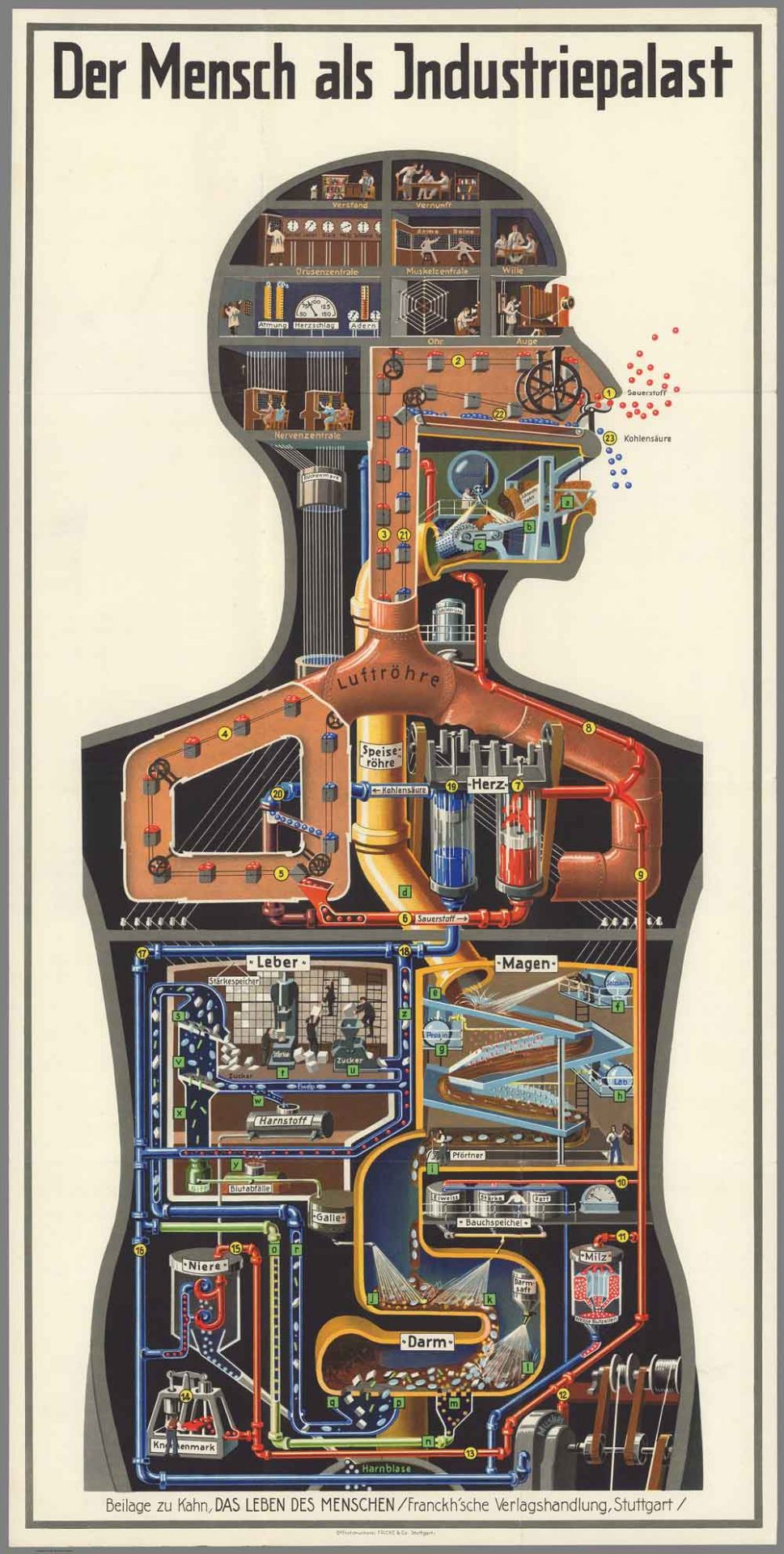

One of the key metaphors of the early modern period was the perception of the body as a machine. The birth of such an idea allowed the development of natural sciences and weakened the role of religion – the body was no longer a mystery, a temple, or something created in God’s image; rather, it had became a complex system governed by the laws of hydraulics, mechanics, and causality. The connection between the mechanical body and the fleeting, immaterial mind remained unclear – Descartes suspected that the pineal gland was responsible. The echoes of these centuries-old discussions are still loud in H.R. Giger’s works – his style is often described as “biomechanical”, and one of the albums of the Swiss author was titled Biomechanics.

The nightmarish fusion of human bodies with complex machinery – pipes, wires, pistons – is the main theme of the works in Necronomicon. We can only surmise what these paintings actually show. Are they humans undergoing macabre experiments on the orders of some totalitarian higher intelligence? Are they perverse spectacles of sadomasochistic pleasure? H.R. Giger’s work asks questions regarding the relationship of humanity and corporeality. If the human mind is separated from the body and connected to a machine, does it remain human? Is a mindless body human? How does the physical act of procreation result with creating new intelligence? H.R. Giger unsettles us so because he makes us realise that our humanity is fully dependant on possessing a faulty, frail, and in some aspects quite disgusting body. In a reality in which a “transfer of consciousness” remains a fantasy, and the existence of the soul an element of faith or an individual hope, “being human” basically means “being a body” – a conclusion which thousands of years of culture have not prepared us for.

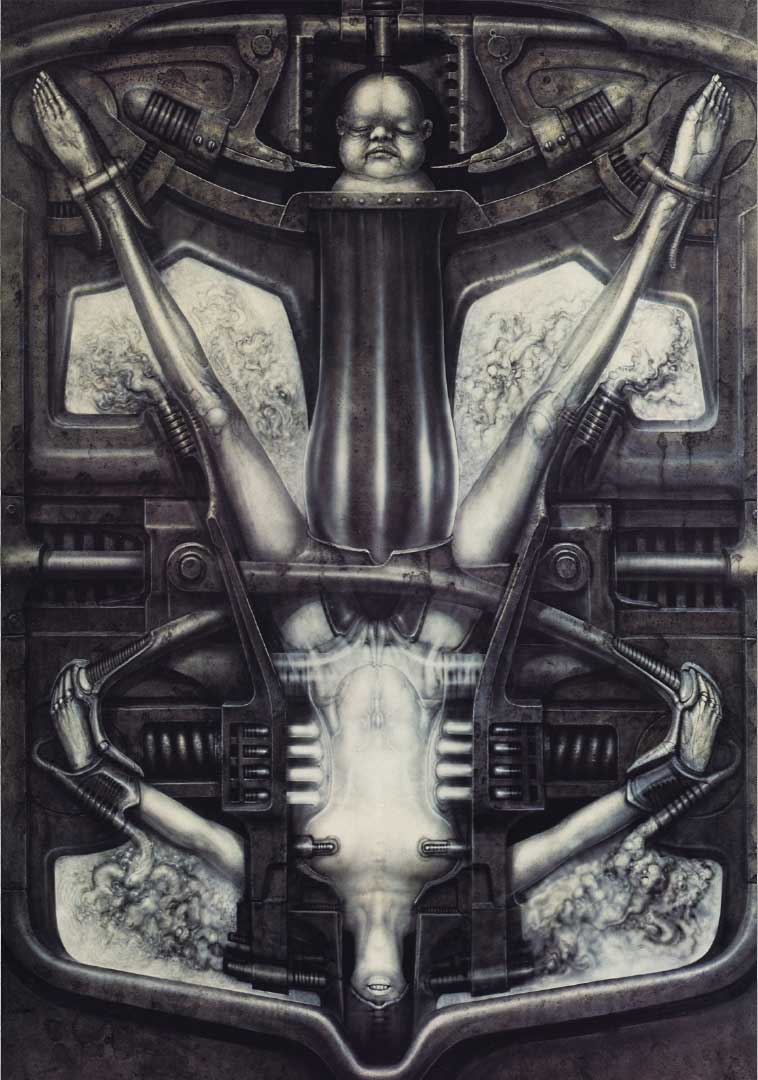

One aspect of corporeality which H.R. Giger found particularly interesting was reproduction – shown from his perspective as a mechanical replication or an act of violence, rather than “the miracle of birth”. In The Visionary World of H.R. Giger, psychologist Stanislav Grof notes that the artist develops a psychoanalytical view of the trauma related to leaving the “paradise” of a mother’s womb through the birth canal by adding a vision of further mechanical torture. The nightmarish, industrial installations are then a metaphor of an unknown, terrifying environment we enter during birth.

H.R. Giger Necronomicon – Alien Made of Fears

If H.R. Giger Necronomicon were to be remembered by only one piece of art, it would absolutely have to be Necronom IV. This particular image was the basis of the Xenomorph design – a monstrous extraterrestrial humanoid known from the Alien movie series. The creature depicted in Necronom IV is partly human and partly inhumane; partly biological, and partly mechanical. The key human element are its arms. On the other hand, the face is insect-like. The long, phallic head and a tail ending with a strange object – maybe a human skull, maybe the creature’s larva – grab the viewer’s attention. The rest of the creature’s anatomy is somewhat unclear – some of it is reminiscent of Cthulhu’s tentacles from Lovecraft’s mythology, while other fragments added to the body are mechanical.

Before Giger’s mysterious creature became the Xenomorph, it had to be redesigned. The head, although still elongated, no longer resembled a penis – after all, the unfriendly alien was meant to be a character in a widely available movie. Its face, on the other hand, became much more monstrous due to the accentuated teeth and a lack of visible eyes. The spike at the end of its tail is reminiscent of a robotic scorpion. The character is closer to a robot than a living creature, though the slime it exudes appears unbearably biological – and is used to immobilise victims, much like a spiders’ web. What makes the Xenomorph look so terrifying? It is a skilful combination of features of fear-inducing creatures (insects, spiders, scorpions) with a humanoid posture; it is a mix of elements we know perfectly well, but in a new configuration yet unknown to nature. The design remains as impressive today as it was in 1979 – it is no wonder that H.R. Giger and the team he collaborated with won an Oscar for visual effects.

The film also shows that the Xenomorph’s look is not as disgusting and terrifying as the way the species reproduces. The Xenomorph queen lays eggs, like an ant or a bee. Next, the so-called facehuggers hatch – these are eight-legged, tailed creatures which attack the faces of potential hosts (e.g. humans) to place an embryo in their throat. When the embryo becomes a larva, it bites its way out through the host’s chest – causing, of course, a painful death. The entire nightmarish, parasitic process combines perfectly with the theme of Hr Giger’s Necronomicon. In it, reproduction is also connected with violence – not only towards the creature being birthed, as mentioned before, but also the one which gives birth and is therefore a “host”.

H. R. Giger Necronomicon – ugliness as Aesthetic Value

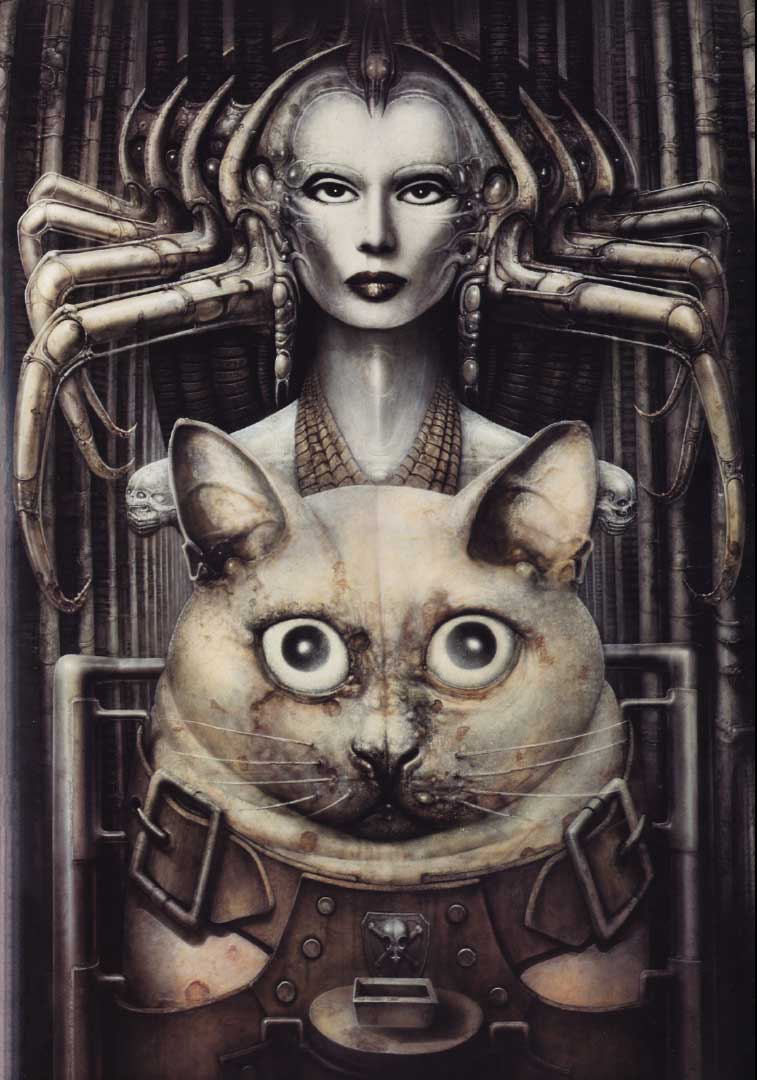

The Polish reflection on literature and art has cultivated the term turpism (from Latin “turpis” – “ugly”) which describes the exploration of the disgusting, revolting, and shocking. H.R. Giger could likely be named a turpist – his art celebrates something most of us would rather not think about. Are the works from Necronomicon exclusively monstrous, and is this their sole purpose? That would be a gross oversimplification. In his works, elements of architectonic education can be noted – monstrous interiors and churning half-mechanical bodies possess certain elements of a gothic cathedral: a kind of exaltation and majesty. In another example, Giger followed Louis Wain’s example by presenting portraits of giant-eyed Siamese cats belonging to his friend, which look quite friendly despite the ghoulish surroundings.

Some exceptions and side features of H.R. Giger’s achievements do not change the fact that his pictures are commonly thought of as attempts to artistically depict negative emotions and parts of life – fear, sense of separation, or doubts regarding human nature. He is not, of course, unique in that; Giger was one creator in a long line of artists exploring the dark and unnerving. The depictions of danse macabre in the late-medieval period, the gothic novel, the literary works of the modernists, even occult rock from the 60s and 70s – even these few examples clearly show that death, decay, violence, and the macabre have always been both repulsive and alluring. The goal of art – or at least not all kinds of art – is not to find easy and pleasant topics to give us comfort. It can also rarely give us any answers; instead, it gives us yet more questions and tries to express what is somewhere at the edge of our experience, beyond rational judgement or even the capabilities of language.

When viewed from the perspective of modern sensitivity, H.R. Giger Necronomicon and other work may appear unsubtle, overabundant, kitschy, maybe even edgy. We have to take into account, however, that the pop-culture which made us familiar with ugliness (and may have even bored us with it) owes its openness to anti-aesthetics in part to Giger. His works inspired not only Alien, but also, to a larger or lesser extent, metal music, Hellraiser, the video-game Doom, cyberpunk, or Matrix – and those are only the most obvious examples. H.R. Giger managed to capture a certain spirit of the twentieth century and crystallise particular (anti)aesthetic propositions.

The 12th century parish church in Paisley, Scotland, had undergone renovations in the 1990s, in which destroyed gargoyles were replaced by new sculptures. The witty sculptor based the design of one of them on the Xenomorph. Photo by Mark Harkin, source: www.flickr.com/photos/markyharky/10317206546.

See also our articles on: 80’s nostalgia, Dark academia aesthetic, and Cyberpunk aesthetic.