“Ripley steps out, WEARING TWO TONS OF HARDENED STEEL. THE POWER LOADER. Like medieval armour with the power of a bulldozer.

~ Aliens script, by James Cameron, September 1985.

In James Cameron’s Xenogenesis the two protagonists, a man and a woman, are hounded by a gigantic robot. The woman manages to flee, but the other is forced over a precipice and hangs perilously over a chasm. The robot leans in to finish him, but a far-off wall panel is forced open, revealing the woman – now encased in a robotic vehicle and ready to do battle for her partner’s life.

The scene was transplanted directly into the climax of Aliens, with the two nameless protagonists replaced by Ripley and Newt. There is no chasm; instead Newt cowers under the Sulaco’s flooring. The Alien Queen takes the place of the robot, the design of which Cameron would recycle for the Hunter-Killer Tank in Terminator. And the woman’s robotic vehicle is replaced by one of the film’s most iconic inventions: a mechanised exo-suit called the ‘powerloader’.

“When I was young,” Cameron told astralgia.com when discussing Xenogenesis’ mechanical ‘outfit’, “my friends and I did this little film with $20,000 from the rich, Mormon dentists out in Orange County … The story we wanted took place on a colony starship bound for another planet with the last remnants of humanity on board frozen. I came up with a device I called ‘the Spider’ that was used to crawl around the outside of the ship to make repairs. It was a four-legged walking machine that used a tele-presence-type amplification: you put your feet in things, you grabbed onto these controls, and however you moved and walked, it duplicated your actions.”

When Cameron wrote Aliens he retooled it from one of his unmade scripts, Mother, and also brought over Xenogenesis’ mechanised vehicle, changing it from a four-legged contraption to a two-legged exo-suit: “A year and a half [after Xenogenesis], The Empire Strikes Back came out with these big walking machines in it. I felt vaguely ripped off, or scooped would be more accurate. So I changed ‘the Spider’ to more of an upright, forklift exoskeleton concept.”

“I don’t remember exactly the origin of the idea. It’s based on a design that I created a few years ago for another story that never got made [Xenogenesis]. That predated the ‘Transformer’ robots, at least as a fad in this country. I think that the exo-skeleton concept has been used in a lot of literary SF.”

~ James Cameron, Lofficier interview, 1986.

Funnily enough, the AT-AT design from Empire was inspired by Syd Mead, who Cameron would later briefly task to design the powerloader. Former ILM employee Joe Johnson told btlnews.com in 2010 that “The snow walkers were from a brochure by Syd Mead for US Steel of these walking trucks going through the snow – we turned them into walking tanks.”

“I started designing it when they went to Pinewood. They constructed the test model with 2x2s and trash bags stuffed with newspapers to get the articulation down. The finished prop was so cumbersome, they had to have guys in black skin suits running it. It was not power operated, it was operated by manipulators out of shot.”

~ Syd Mead, Vulture.com. 2013.

Cameron decided to use the powerloader because he did not want Ripley to have the safe distance that a gun could give her when fighting the Queen. Instead she would have to physically tangle with her enemy in an atavistic display of motherly instinct. “I wanted to have the final confrontation with the Alien be a hand-to-hand fight,” Cameron said about the origin of the scene. “To be a very intense, personal thing, not done with guns, which are a remote way of killing. Also, guns carry a lot of other connotations as well. But to really go one on one with the creature was my goal. It made sense that Ripley could win if she could equalise the odds. So there had to be some way of amplifying her strength, in a way that was not a comic-bookish sort of concept, like taking a pill.”

“At a certain point, I was toying with the idea of having the Marines have battle suits,” he said, taking a page or two out of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers. “But then I thought, ‘oh, no, you’re going to see that coming a mile away’. Anyway, how would Ripley know how to operate a battle suit? They wouldn’t be teaching her. It was really critical to the story that she emerge under pressure as the person who really takes control. They discredit her at the beginning; the last thing they’d do is hand her a gun and teach her how to use a battle suit.”

Cameron discarded the idea of using a battlesuit (a weapon) and stuck with the concept of a mechanoid forklift (a tool). But he still wanted to assure the audience that Ripley could operate it. Depicting the powerloader as a rather rudimentary device (at least in the world of Alien) enabled Ripley to use it with relative ease.

“She had had to support herself as a dockworker at Gateway Station [so] it was logical to assume that she might know how to handle a basic piece of cargo handling equipment,” said Cameron. “You had to set it up. You had to see her volunteer to help unload the ship and impress them all that she could do it. Otherwise you’d never believe that she could duke it out with the Alien Queen.”

In Cameron’s original treatment the powerloader is revealed during the climax before it walks into the hanger to fight the Queen. The treatment describes a sequence of shots showing Ripley strap herself into the suit. We are then given a full shot of Ripley in the powerloader. Cameron omitted this in later scripts (but kept the cuts of her strapping in to something) to get the money shot we know from the film. The shots of her strapping in were kept in all of the subsequent drafts, but none of it was ever shot (though many fans believed that the footage had in fact been filmed – it’s usually recounted in those ‘I saw a different version on TV as a kid’ stories).

“I was particularly proud of being involved in the sequence involving the Alien Queen and the powerloader,” said Special Effects technician Joss Williams, “because right from the start of my involvement on the movie, we had pictures drawn by Jim -of which today you’d get computer generated images, but this was hand drawn by Jim- of the powerloader fighting the Alien Queen.” Turning Cameron’s painting into a reality would require not only full-scale models but miniatures as well.

Building the large powerloader was left to Special Effects Supervisor John Richardson. Richardson’s tenure on the film see-sawed from having near total control of his workshop, to suddenly working under Cameron’s peregrine-eyed supervision. The director would often check in and make amendments to the design, offering sketches to a bemused Richardson. “A lot of directors would have said, ‘I want it to look like a walking forklift,’ and let it go at that,” Richardson told Cinefex in 1986. “Jim would say, ‘I want it to look like a walking forklift and those little bolts up there have to be this shape.'”

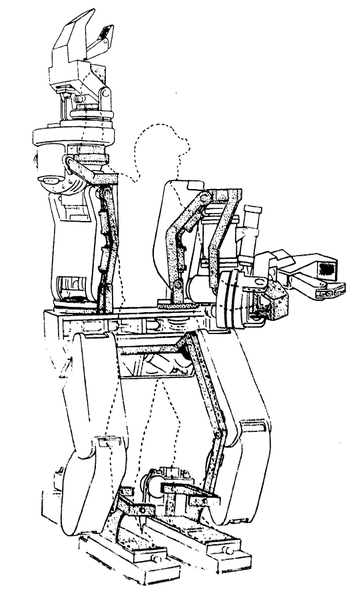

The Hardiman I prototype, the first attempt to build a practical powered exoskeleton, by General Electric between 1965 and 1971.

“Jim is a very hands-on director,” Richardson explained further. “We were trying to cut just as many corners as we could just to get it ready in time, but Jim would suddenly get locked in on the shape of the screw head in the back corner of the heel of the boot. And we were just screaming to get the thing ready.”

The two would quarrel over the details, but they unanimously agreed that the outcome was the better for it. Richardson recalled that “I seem to remember once or twice on a Friday night, a bottle of champagne would turn up in the workshop with a little note from Jim saying, ‘Building powerloaders is thirsty work. Have one on me.’ And it sort of smoothed everything out until the Monday … They were good times.”

The delays with the large powerloader meant that delays with the miniature were inevitable, since the miniature was based directly on the larger model. “They were working on the full size one right up until the time they started shooting it,” said miniature designer Phil Notaro, who helped build the Queen and powerloader miniatures with Doug Beswick, “so I actually couldn’t finish the puppet until I got over there [to Pinewood studios] and saw it. ‘Aha! That’s what it looks like!’ … It was pretty tense for a while there, though, because we were halfway into our schedule and we hadn’t even started the powerloader yet.”

The final battle between Ripley and the Alien Queen was among the last scenes to be shot for the film. The full scale powerloader, weighing around 600lbs and fabricated out of aluminium, fibreglass and PVC plastic, was controlled from within by a stuntman (John Lees) who was obscured inside the machine – just like the Alien Queen puppet, which contained two stuntmen. “I remember the English visual effects guys thinking we were crazy,” said Cameron, “the way we wanted to do it. And I said, ‘No, it’s the gag where the dad lets the daughter walk on his feet.’”

The back of the prop was given hidden counterweights disguised as machine components. The mechanics inside the hands were crafted to be light enough so the whole thing wouldn’t fall face first into the ground (Weaver related that this happened many times in rehearsal). The wrists were radio controlled. The ‘pincers’ were operated by cables. Also like the Queen puppet, the powerloader was held up by a rig (expertly hidden by Cameron’s framing) for its entrance into the hanger bay. For other scenes it was supported by a pole up the spine or by a counterweighted crane.

Sigourney Weaver, by all accounts, was very professional when it came to being strapped inside the contraption or placed on the sidelines all day. Cameron had predicted that the effects-heavy scenes would require many takes, re-calibration, and luck to get right. Weaver, he reckoned, would be naturally bored and tired during such a complex process, but the opposite was true. “She was just wonderful about the whole thing,” Cameron said. “She was a complete pro and very tolerant when it came to standing around the set for hours doing the predicted take after take.” Weaver herself felt that the sequence was worth it. “I loved that,” she said. “That’s, I think, one of the favourite moments that people have: that battle, ‘get away from her, you bitch!'”

But Weaver did have to contend with one uncomfortable element during the shooting: the effects team’s sense of humour – a balloon was inserted into the powerloader, just behind Weaver’s buttocks. Whenever the camera rolled, the crew would pump air into the balloon through a pipe. Weaver ran through several explanations for the bulge at her backside, with some involving the stuntman, John Lees, concealed behind her. “She thought he was getting a boner all the time,” laughed Richardson. “She was going, ‘John, John? What are you doing, John?’ She couldn’t move because she was strapped in, and (John) didn’t know because he was nowhere to be seen [inside the loader].”

“It was very funny,” said Weaver, “because it lasted quite a long time, a couple of hours. I was thinking, ‘Well, this is interesting.'”

The scenes featuring the miniature loader and Queen were filmed after principal photography had ended. The powerloader miniature was moved around a small scale set by rods placed through the floor and the model’s feet. The arms were cable operated. The model was fitted with a small doll in the form of Ripley. For the scene earlier in the film where Ripley demonstrates her prowess with the loader for Hicks and Apone, we can see another powerloader being operated in the background – this was a miniature plate filmed much later; the pilot is in fact the Ripley doll redressed as a Marine.

The miniature powerloader’s final scene, tumbling out of the airlock, was literally its final scene: the model allegedly plummeted through the star field backdrop and smashed to pieces on the concrete. “We did about eight takes on it,” said Notaro, “and each time it crashed into pieces. We’d then have to superglue it back together and do it again.” On the ninth shot the miniature broke beyond repair. “It exploded,” recalled miniatures technical supervisor Pat McClung.

Cameron had worried that the scene with the powerloader would not be taken seriously by the audience if it was anything short of stellar – if the images in his head could be conjured and guided by an expert (and careful) hand, then he figured they would accept it. It would all hinge on the execution. “There are always certain things on every film that you’re nervous about,” he said. “You like the challenge. The challenge is, can I make the audience believe this? Then you’re nervous about it the whole time, which is good. The more nervous you are, the more you’re going to set it up and make it work.”

“It always stuck in my mind,” said Joss Williams, “and it still does today – the sequence when we actually shot it onstage at Pinewood of the powerloader that we built and seeing the Alien Queen that Stan Winston had built, fighting. And it was just what Jim had drawn some eighteen months, maybe two years, previously.”

“When the film opened,” explained Cameron, “I went to the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. When the spaceship door came up, and there was Sigourney in the powerloader, the audience went apeshit! That’s what it’s all about. It really taught me to not be afraid of the challenges, to find them, to seek them out because that’s where the magic is.”

The powerloader sequence was such a nice way to off the Queen, but is also intelligently placed to book-end subtext from the first act. Ripley is affected badly by her experience on the Nostromo, and we begin to see her desire (commensurate with her character) to surmount that fear and not be prisoner to it – ‘you’re going there to wipe them out, not to study’ etc. By giving her a visceral, believable hand-to-hand fight with the Queen, she is very outwardly engaging it on its own level of savagery, in turn providing a primal release for her primal feelings regarding her experience. Tidy!

Good article as ever, V.

The catharsis with Ripley is very satisfying, and it helps that the Queen’s interest in the fight is more than her being simply monstrous – she’s a mother too, looking to wreak revenge on her children’s killer. It makes her a deadlier and more considerable opponent.

I think there’s also something in there about using an artifact of her disgrace as a means to ultimately prevail.

Absolutely. I suppose she can be strangely grateful that she was punished in the first place.

Another benefit of doing it this way is that it’s much more dramatic.

Nothing in the film or the source material indicates that the queen is any more well-armored than the drones. Consequently, a few 10mm rounds from a pulse rifle would blow her head or abdomen to pieces, and her head is a lot easier to hit than the average drone’s.

Incidentally: according to the Colonial Marines Technical Manual, the pulse rifle and smart gun fire 10x24mm rounds. That is: the slug is 10mm wide at the base, and length of the propellant charge is 24mm from the base of the slug to the base of the charge. This is similar to the 9x19mm Parabellum round used by many semiautomatic pistols today: 9mm wide at the base, 19mm from the base of the slug to the base of the shell casing. For reference, the standard-issue NATO round used by the M4, the M16, and the M249 SAW is the 5.56x45mm round — 5.56mm wide at the base, and 45mm from the base of the slug to the base of the shell casing. Meanwhile, the AK-47 fires a 7.62x39mm round — bigger around than the standard-issue NATO round but with a slightly shorter shell casing.

At first glance, this suggests that the pulse rifle and smart guns are essentially firing pistol rounds, which seems ludicrously underpowered to me, particularly given that wider projectiles tend to be more more difficult to stabilize without a longer barrel and more propellant, which is why the 5.56mm round is so small — it flies faster and achieves tighter shot groupings at long range than the 7.62mm round, though there is an extent to which it lacks the raw stopping power of the 7.62mm round — Delta operators in Mogadishu complained that using armor-piercing nylon-jacketed 5.56mm rounds was like trying to kill someone with an icepick. For this reason, the military still fields 7.62mm rifles such as the SCAR-H; likewise, the military considered using a compromise, the 6.8mm round.

That said, there are two additional considerations that would influence the efficacy of the 10x24mm round, both of which were mentioned by Gorman in the film:

1). 10x24mm rounds are explosive-tipped

2). 10x24mm rounds are caseless — that is, they do not have a shell casing containing the propellant. Instead, they use a hard, molded plastic explosive as propellant (triggered, in this case, by an electric pulse — hence, “pulse rifle”). Caseless rounds were conceived to save on weight and brass: brass is expensive, and lighter ammunition means a soldier can carry more ammo.

Naturally, an explosive-tipped round will not need to hit a target very hard to do damage, but the round still has to hit its target to do so. Which leads us to the issue of propellant.

According to the Technical Manual, the chemical composition of the caseless propellant of the 10x24mm round is Nitramine 50, which is a mythical plastic explosive that is efficient enough to achieve muzzle velocities of 840 meters-per-second, which is around that of a 5.56x45mm round fired from a 13 inch barrel.

According to Wikipedia, nitramine is in the same chemical family as nitramides such as RDX and HMX; RDX was one of the first plastic explosives and was used during WWII, and HMX is used as a solid rocket fuel.

Unfortunately, we are nowhere near caseless rounds of comparable efficiency. For one thing, caseless compounds tend to be fragile. For another, maintaining gas pressure in the chamber (to push the shell casing through the barrel) is difficult when the casing itself disintegrates when fired (potentially leaving a large hole through which gasses may escape). Lastly, the damn things have a tendency to overheat and cook off in a weapon that has undergone sustained usage. The closest we have is a hexogen/oxogen propellant produced by the Lightweight Smallarms Technology program (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LSAT_caseless_ammunition).

Still, it’s an interesting case of forward-looking on the part of James Cameron and the other folks who made the film.

I don’t know much about weaponry; I looked into some of it years ago but it’s bewildering to me. Weren’t 10mm auto rounds used in Heckler & Koch’s MP5/10 machine-gun? Apparently, due to high stopping power and performance, the round is still used by several special forces agencies. I heard that Heckler & Kock also designed caseless bullets that never managed to catch on. HK G11 caseless rounds ensure

Unfortunately for the Colonial Marines explosive rounds typically start from 20mm rounds, not 10mm, but I’m sure they have that licked in 2179 😀

9x19mm rounds have undeniable stopping power, which is why they’ve been in use for about 100 years in both and pistols and submachineguns, including the HK MP5 that you mentioned. The 9x19mm round has qualities that are particularly useful in urban environments, including high stopping power at close range and low overpenetration (meaning you can shoot someone and not have to worry about the bullet going through them). For this reason, they are often used by law enforcement agencies.

But these same qualities detract from their usefulness in a warzone.

Because they are relatively large, stubby objects, 9mm slugs don’t have the same aerodynamics of smaller slugs such as the 5.56mm or 7.62mm. For this reason (and also because the 9x19mm shell casing tends to contain less propellant), 9mm rounds tend to wobble more, fly slower, and slow down faster than the 5.56mm and 7.62mm rounds. This makes them less effective than rifle rounds beyond short-to-medium ranges.

The HK G11 was one contender in the US military’s Advanced Combat Rifle program (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Combat_Rifle), which intended to replace the M16. There were a couple of flechette rifles, too.

Incidentally: the Voere VEC-91 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voere_VEC-91) is a bolt-action caseless rifle that uses (wait for it) electrical impulses to trigger the caseless ammunition. This makes a certain kind of sense: if you can find an explosive compound that is sensitive to electricity but not heat, you can ignite the rounds without worrying about them cooking off (whilst taking one step closer to the pulse rifles of Aliens).

I would just assume the caseless propellant is more efficient than nitrocellulose bonded cordite when you’re interpreting the cartridge dimensions. The explosive in the 10mm case would have to be something pretty spectacular as well, to have such a small projectile with so little space for a warhead and/or with such poor sectional density pierce light armour.

It’s not the propellant of the 10x24mm round that bothers me, it’s the aerodynamics of the slug itself.

In general (sorry to repeat myself), bigger bullets wobble more, travel slower, and slow down faster; these problems can be mitigated somewhat with more propellant (or more powerful propellant) and a longer barrel (a longer barrel gives the slug more time to receive momentum from the expanding gas behind it, though there are certain limits on barrel length owing to things like friction and barrel components), it doesn’t change the fact that a 10mm round is gonna have more drag than a 5.56mm round — which would be a liability for an all-purpose weapon.

Smaller isn’t always better, of course — I return to the example of the Delta operators in Mogadishu complaining about the armor-piercing 5.56mm rounds they were using, which would leave such tiny entrance and exit wounds that victims would often get to their feet after being shot.

The trick is to find a firing solution that delivers accurate, high-velocity rounds that are large or powerful enough to put someone down.

A few advantages to caseless technology are that you don’t have to have any metallic casing. In a 9x19mm round, the cartridge is only about 2/3 of the way full of powder. THe rest is metal and empty space, in and around the cartridge. Caseless cartridges are prismic, rather than cylindrical, which means there is a better degree of spatial efficiency, since the propellant is essentially “cast” around the slug, rather than dumped into a tiny, machined tube behind the slug. THis dramatically reduces the physical size of ammunition, as well as its weight, and dramatically increases the firepower per volume unit of ammunition. The drawback to this being the fact that the weapon no longer has an ejectable heat-sink to draw so much of the heat produced during each shot, out the side.

The advances in metallurgy do away with our concern for overheating as well as the improved handling of higher chamber pressures. We just don’t have that yet IRL. 😀

An interesting point of reference: the famous and still useful .357 Magnum round introduced in 1934 is defined as a 9×33. The bullet is nominally 9.1mm in diameter. Ruger sells the .357 Magnum Blackhawk single-action revolver in a convertible model with a interchangeable 9mm Luger cylinder in the box. The .38 Special is in the same family, making the Blackhawk a very versatile piece. Shoot what you got.

Pingback: Cinetropolis » James Cameron And The Xenogenesis Of Aliens’ Powerloader

Pingback: The Risk Always Lives: Words to Live by On the Set of James Cameron’s ‘Aliens’ • Cinephilia & Beyond