Today the WGNSS Botany Group ventured into Illinois for its Monday field trip to explore the limestone bluffs and hilltop prairies of Salt Lick Point Land & Water Reserve. This being the first day of autumn, goldenrods and other fall-blooming plants in the great family Asteraceae were expected to dominate the flora, which indeed was the case. Along the steep, rocky trail leading up to the prairies, Solidago buckleyi (Buckley’s goldenrod) and S. ulmifolia (elmleaf goldenrod) bloomed together in the dry-mesic deciduous forest. The former is a near-Missouri specialty, extending just barely into nearby portions of four adjacent states, and can be distinguished by its relatively larger flowers on columnar inflorescences with recurved involucral bracts and its relatively broad leaves with distinct teeth.

As we walked the trail, I heard several cicadas singing, starting with Megatibicen pronotalis pronotalis (Walker’s annual cicada) near the bottom and Neotibicen robinsonianus (Robinson’s annual cicada) as we ascended, the latter eventually joined also N. lyricens (lyric cicada). Carcasses of the latter two were also seen along the trail (confirming my IDs based on their songs), and as we reached the second of three significant hilltop prairie remnants Kathy found a live male M. pronotalis in the low vegetation. It’s noisy, rattling alarm screeching as I held it attracted a crowd of gawkers within the group and a flurry of photographs before I secured the specimen in a pill bottle and recorded the location. Like most cicadas, only the males are capable of making sound, which they do by rapidly expanding and contracting hard membranes called tymbals that reside under distinctive plates found on the venter at the base of the abdomen.

Goldenrods were blooming profusely in the prairie, attracting numerous insects including Lycomorpha pholus (black-and-yellow lichen moths)—a mimic of netwinged beetles in the genus Lycus.

As the trail continued along the blufftops, we found a true bluff specialty—Solidago drummondii (bluff or Drummond’s goldenrod). Like S. buckleyi, this species also is very nearly a Missouri endemic and is found exclusively on or very near limestone/dolomite bluffs. It’s habitat and very wide, toothed leaves on short petioles easily distinguish this species from other goldenrods.

In the interface between the dry-mesic deciduous forest and another hilltop prairie, we saw a nice patch of Agalinis tenuifolia (slender false foxglove), distinguished by its thin, branching stems, opposite, linear leaves with long, thin pedicels, and small flowers with upper lip arching over and enclosing the stamens.

As I photographed the plant, I heard others in the group on the prairie saying “We need an entomologist,” and as I approached the group I found them surrounding a Brickellia eupatorioides (false boneset) hosting two individuals of the large, black planthopper, Poblicia fulginosa. Although normally very wary, both individuals cooperated nicely for photos, and I succeeded in capturing a photo showing the bright red markings on their abdomen in obvious contrast to the otherwise dark, somber coloration of the insect. In fact, the dorsal portion of the abdomen is entirely bright red, presumably serving a “flash coloration” function similar to the brightly colored abdomen of jewel beetles or hind wings of underwing moths to confuse potential predators by its high visibility in flight and sudden disappearance when the insect lands and folds its wings over the abdomen.

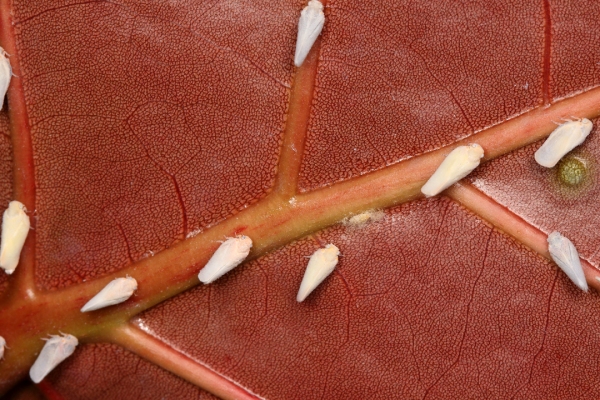

As we continued past the hilltop prairie, several individuals of Sideroxylon lanuginosum (gum bumelia or woolly buckthorn) were found along the dry ridgetop trail. Whenever I see S. lanuginosum, I look for signs of Plinthocoelium suaveolens (bumelia borer)—arguably North America’s most beautiful longhorned beetle. No signs were seen at the first tree, but at the second the telltale frass (digested sawdust ejected by the larvae that bore through the main roots of living trees) was easily spotted at the base of the trunk. This beetle is distributed across the southeastern and south-central U.S. wherever it’s host can be found, occurring reliably as far north as the dolomite glades south of St. Louis; however, I am unaware of any records of this beetle from Illinois.

After a long, steep, rocky descent back down, we found many more S. drummondii perched poetically on the vertical limestone bluff face at the bottom.

The walk back to the parking lot gave us the opportunity to study several additional fall-blooming asters including Solidago altissimum (tall goldenrod), S. gigantea (giant goldenrod), Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke), and Smallanthia uvedalia (bearsfoot). While H. tuberosus is easily recognized by gestalt, John Oliver pointed out the main identifying characters that distinguish the species from the mutitude of other sunflowers such as leaves becoming alternate at the upper reaches of the stem, the rough, scabrous stem, and the basal “wings” on the distal portion of the leaf petioles, particularly the lower leaves.

Smallanthia uvedalia, on the other hand, is much less common but immediately recognizable by its unique flower heads with few, well-spaced ray florets and large, maple-like leaves.

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2021