Tales From the Terminals: Liverpool Street…. From Bedlam to Kindertransport (Part One)

Having covered the corridor of stations which lie along the Marylebone and Euston road, we now move down into the City and onto one of the capital’s busiest terminals- Liverpool Street Station.

Liverpool Street (the road rather than the station) in its present form dates back to 1829 and is named after Robert Jenkinson; aka Lord Liverpool, a long-serving Prime Minister who was in office between 1812 and 1827.

Lord Liverpool

Liverpool Street is not the first road to provide passage along the route.

The modern road was predated by a lane known as Old Bethlehem; a winding path which had existed for centuries; its name deriving from the fact that Bethlehem Hospital once stood on the ground now occupied by the station.

Bethlehem was no ordinary sanatorium… also known by its more infamous name, Bedlam it was London’s (and the world’s) first psychiatric hospital…

16th Century map (the ‘London Copperplate’) showing the location of Bedlam Hospital. The long, wide road to the right is the present day Bishopsgate; still a major route through the City (image from the Museum of London)

Bethlehem Hospital

The institution, which lay just outside the old city wall, first began caring for the mentally ill (or, as they were known back then, ‘distracted’) patients in 1377.

The term, ‘cared for’ however is grossly inaccurate.

Bethlehem Hospital was a hellish place, where patients were chained to their beds and considered to be no more than wild beasts.

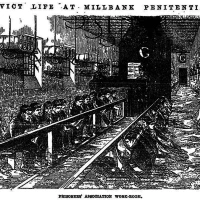

Contemporary sketch of life inside Bedlam…

When heavy irons weren’t enough to keep them under control, patients were whipped or plunged into cold water in fruitless attempts to stifle their madness.

It comes as no surprise therefore that the word ‘Bedlam’- an old corruption of the hospital’s name- has passed into the English language as a phrase denoting a place of utter chaos and despair.

In 1676, the hospital moved a few hundred yards to Moorfields (where Finsbury Circus now lies), just across the road from where Liverpool Street station is now situated.

Original map showing the location of the second Bedlam Hospital which was located where the present day Finsbury Circus now lies

Designed by Robert Hooke, who was Sir Christopher Wren’s right-hand man, the new building was a very grand affair indeed.

The second, grander Bedlam Hospital- the broad road in front is London Wall

The gates to the new asylum were presided over by two large sculptures; Madness and Melancholy.

Crafted by Caius Gabriel Cibber (who also created the impressive relief at the base of The Monument) the two statues are now held in the Bethlem Royal Hospital archives in Beckenham and can be seen in this following short clip from the BBC4 series, Romancing the Stone: The Golden Ages of British Sculpture:

It was within the new Bethlehem hospital that the notorious- and highly profitable-practice of inviting the public to come along and gawp at the patients first began.

Special galleries were incorporated into the building’s design for the purpose; small arenas where the patients were paraded like creatures in a menagerie.

An idea of what this process looked like can be garnered from William Hogarth’s innovative series of paintings, The Rake’s Progress.

Produced between 1732-33, Hogarth’s masterpiece consists of eight artworks which chronicle the decline and fall of Tom Rakewell, a young man who, after coming to London, is seduced by gambling, partying and prostitution.

Tom’s binge inevitably ruins him and, in the final picture, Hogarth portrays the Rake’s tragic demise as he succumbs to madness, his final days spent languishing in the pandemonium that is Bedlam whilst fan-fluttering ladies of high society look on…

The Rake’s Progress, William Hogarth (1730s)

If you wish to see original Rake’s Progress, it can be found within the wonderful Sir John Soames Museum at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

*

In 1815, Bethlehem Hospital moved out of the area for good, establishing a new home south of the Thames in Lambeth. During the move, patients were transferred to the new hospital in a fleet of specially chartered Hackney carriages.

Today, the Lambeth asylum is still in existence… although the building now serves a different purpose- it is home to the Imperial War Museum… where illness afflicting the mind has been swapped for the insanity of modern warfare…

The third Bedlam… now the Imperial War Museum

The Railways Move In

The first station to arrive in the Liverpool Street area was the now vanished Broad Street, which opened in 1865 and remained in service until 1986 (an earlier post all about this former station can be found here).

Liverpool Street Station followed a few years later, opening next door to Broad Street in 1874 as the London terminal for the Great Eastern Railway.

Before their grand station opened, the Great Eastern had operated a smaller terminus just outside the City boundaries called ‘Bishopsgate’, which opened in 1840 on the junction of Shoreditch High Street and Bethnal Green Road.

Bishopsgate Station; the prelude to the Liverpool Street terminal (photo: Subterranea Britannica)

The site remained in use as a freight depot until December 1964, when it burnt down. Today, the location is once again in use by the railways, with the London Overground’s recently opened Shoreditch High Street station occupying the former derelict land.

*

The architect behind Liverpool Street station was Edward Wilson; a Scotsman who was born in Edinburgh and was the Great Eastern’s chief engineer.

Liverpool Street in 1896 (photo: Wikipedia)

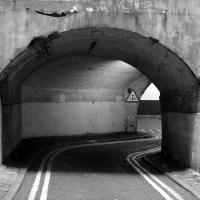

As regular users of Liverpool Street will know, the tracks actually lie below street level and one must descend stairs or escalators to reach their desired platform.

Liverpool Street’s two levels can be seen here- the balcony is at street height whilst the lower concourse, where trains arrive and depart, is below ground.

The reason for this is that the platforms were originally designed to provide a seamless link with the London Underground’s Metropolitan line.

At the time, The Great Eastern was a business partner of the new-fangled underground railway, so a smooth link-up with the subterranean system was considered to be financially beneficial.

Original emblems of former business partners, the Great Eastern and Metropolitan railways

In order to achieve this connection, the Great Eastern had to plough their tracks into Liverpool Street down a steep gradient, sending trains on their last leg steaming and groaning through a complex of dingy tunnels; a dismal approach to the metropolis which is still in use today.

The partnership between the two companies was eventually severed, and the novel set-up was condemned by Lord Salisbury- one of the Great Eastern’s chairmen- as being “one of the greatest mistakes ever committed in connection with a railway.”

The Great Eastern Hotel

In 1884, a grand hotel- The Great Eastern was added to the station which, for many years, was surprisingly the only hotel in the historic square mile.

The Great Eastern Hotel (now the ‘Andaz’)

The Great Eastern Hotel was designed by Charles E. Barry (Junior), son of Charles Barry (Senior) who was one of London’s greatest architects; the brains behind landmarks such as Trafalgar Square’s precient and the Houses of Parliament.

Charles Barry Junior was very much a chip off the old block, his design for the Great Eastern Hotel being very grand indeed.

Early 20th Century advert for the Great Eastern Hotel (image from the National Railway Museum)

When it opened, the hotel boasted a glass-domed roof and no fewer than two Masonic temples.

A siding from the station was extended to reach beneath the hotel, creating a service area from where trains could take away the hotel’s waste and haul in coal to keep the well-heeled guests nice and toasty.

The Great Eastern Hotel also boasted seawater baths, the sloshing liquid being brought in from the coast by goods trains.

Speaking of water, when The Great Eastern Hotel was being constructed, it was impossible to lay down sewerage pipes due to the tunnels of the London Underground’s Metropolitan line being in the way.

As a result, the hotel had to improvise… resulting in a vacuum-flush system being designed, which to this day sees waste being sent rushing upwards! Probably best not to think about it whilst resting on your hotel bed!..

Today, the hotel- which was refurbished between 1997-2000 at a cost of £65 million- has been renamed The Andaz and is still an extremely lavish destination boasting five restaurants.

If you can’t afford a night or two at this lavish destination, the hotel is often open for public viewing during the excellent Open House weekend.

*

Notable Passengers

It was at Liverpool Street Station, one morning during the summer of 1886, that Joseph Merrick- aka ‘The Elephant Man’ was mobbed by a ferociously nosy, rush-hour crowd.

Prior to this incident, Joseph had been in Belgium where his famous deformities were pedalled in a travelling ‘freak show’.

However, by the late 1880s, such exhibitions were in decline and, seeing Joseph as a financial burden, the Elephant Man’s manager abandoned his protégé, stealing Joseph’s life savings to boot.

Penniless, frightened and alone, Joseph eventually managed to secure passage on a ferry to Harwich and, once arriving in the port, he boarded a train to London’s Liverpool Street.

Once at the busy station, his shuffling gait, oversized cloak and canvas hood quickly drew attention and within moments, Joseph was swamped by baying spectators; a nightmarish echo of the days when Bedlam existed on the site.

The terrifying event was included in the 1980 film, The Elephant Man, starring John Hurt. The scene was filmed on location at Liverpool Street itself:

Following this incident, Joseph was rescued by two policemen and taken by Hackney carriage to the Royal London Hospital where he would spend the rest of his tragically short life.

I have devoted two earlier posts to Joseph Merrick’s life and his time in London elsewhere on this website- to read please follow the links to part one here and part two here.

*

Thanks to its close links with Harwich port, Liverpool Street was also responsible for introducing some of the 20th century’s most famous left-wing political figures to London- namely the communists, Maxim Gorky, Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky (who famously suffered a nasty death when he was murdered with an ice-pick)… and the terrifying future tyrant, Joseph Stalin.

(From left to right) Maxim Gorky, Leon Trotsky, Rosa Luxemburg and and a young Joseph Stalin who arrived together in London via Liverpool Street Station

It was in 1907 that this as yet unknown group of communists travelled to London in order to attend a political conference.

In a way, it was also a spiritual journey, as their communist ideology was born in London, formulated by Karl Marx who resided in the slums of Soho and sought refuge with his writing in the British Library.

At Liverpool Street, the red-bunch were met by a small group of journalists and supporters, along with another famous party-member… comrade Vladimir Lenin who was already in London.

Upon greeting his comrades, Lenin announced that he was pleased they could come along for the event, and that they could expect a “fine old scuffle.”

Vladimir Lenin, who welcomed his Russian comrades at Liverpool street in the early 20th century

The young Stalin… the future dictator who would go onto wreak so much death and misery upon his own people, did not have far to travel from Liverpool Street to his new digs… he spent his time in London at a doss house on Fieldgate Street in Whitechapel, just over half a mile from the station… but that of course, is another story altogether…