-

ID Tips for Lichen Newcomers

How do you start figuring out lichens if you’re a novice, especially if you have no keys? With 85% of my books, including lichen ID materials, still in storage (long story), I’m thrown on the resources of the internet. Here are a few suggestions for exploring lichen basics (off-site links open in a new window):

There is an online lichen key from the UK for 60 British lichens on twigs (from the Natural History Museum at South Kensington); they also have a glossary of terms. To get started, choose whether the lichen is fruticose, foliose, or crustose. (See descriptions at our Shapes and Sizes page if you’re not sure.) You eventually get to a color photo of the lichen. If you get one or more results, don’t assume the species is right, but it might at least point you to a genus to check out. (I got a lot of “no results” on my searches, but I was just making up characters.)You might try checking photos at Ways of Enlichenment, which does a good job of showing many species in each genus.

Steve Sharnoff offers some lichen basics at his website. He also has lots of photos available that may also be helpful, but this site is focused on North America. Some species, however, are widespread, and many genera are.

If you narrow it down to a few species, you can check whether they occur in your area at this database maintained by the Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria (CNALH). Their records include specimens from all over the world. If you go to their dynamic map and click on your area (and specify a radius to search), they will generate a checklist that you can also use as an interactive key. Very nice!!

Only the lichen portal at CNALH will give you a detailed description of important characters, but at least the others provide visual references.

Note: Also posted this on iNaturalist as a journal entry.

-

The Latest Lichen News

Yes, we’re back, and there’s news in the world of lichens. Please forgive the long “dormancy,” of which more is explained below. But right now, things are popping in the world of lichens, and we thought we’d better attempt to update ourselves just a tad.

The Overlooked Organisms That Keep Challenging Our Assumptions About Life, at The Atlantic. As they say, “Gorgeous and weird, lichens have pushed the boundaries of our understanding of nature—and our way of studying it.” (by Ed Yong Jan 17, 2019)

[Or maybe not so “latest” after all. Here’s an earlier article about the researcher who put this idea together, Toby Spribille, also by Ed Yong, in the Atlantic in 2016.]

We’ve talked before about the fact that some lichens contain multitudes—specifically, representatives of not just two but THREE kingdoms within their symbiosis. Now, researchers are demonstrating that the situation for some lichens may be even more complex.

Hooray for lichens—the organisms that continually surprise us!

Lichen-forming fungi [all*] belong to a group called the ascomycetes. But in 2016, Spribille and his colleague Veera Tuovinen, of Uppsala University, found that the largest and most species-rich group of lichens harbored a second fungus, from a very different group called Cyphobasidium. (For simplicity, I’ll call the two fungi ascos and cyphos).

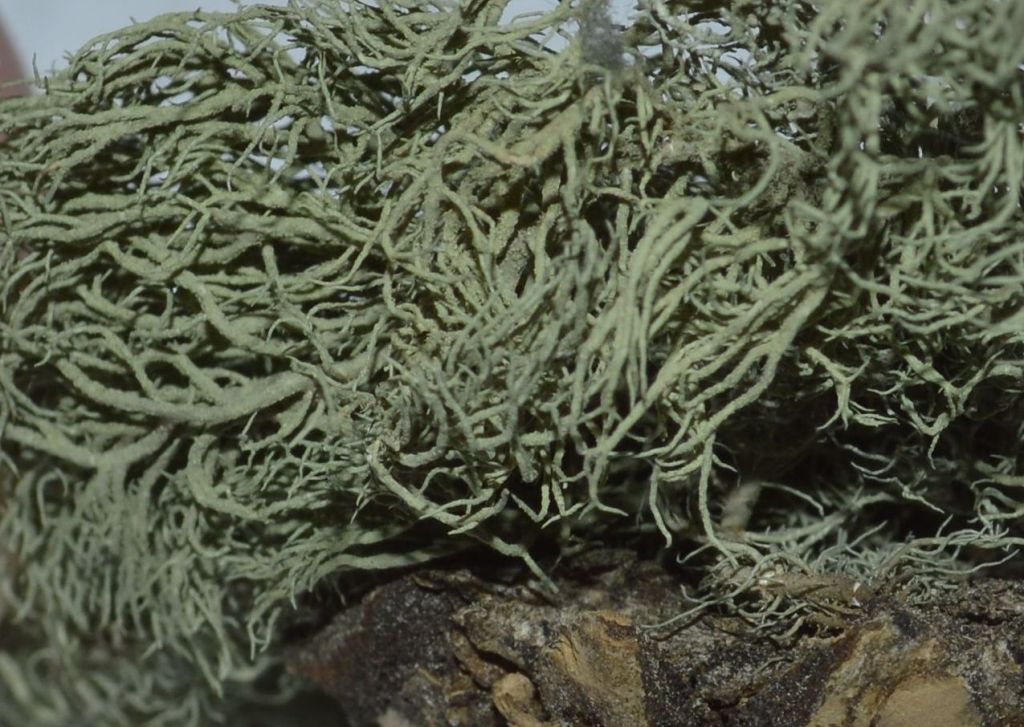

Look on the bark of conifers in the Pacific Northwest, and you will quickly spot wolf lichens—tennis-ball green and highly branched, like some discarded alien nervous system. When Tuovinen looked at these under a microscope, she found a group of fungal cells that were neither ascos nor cyphos. The lichens’ DNA told a similar story: There were fungal genes that didn’t belong to either of the two expected groups. Wolf lichens, it turns out, contain yet another fungus, known as Tremella. —Ed Yong

Bright green wolf lichen (Letharia vulpina) outshines pale Usnea (beard lichens) in this photo from C. Tom Hash (https://www.inaturalist.org/users/7893, used by permission).

* There are, as I understand it, a few lichen-forming Basidiomycetes as well. But for practical purposes… ascomycetes.

Tremella is commonly known to us ordinary mortals as “witches’ butter” and is a parasitic jelly fungus that seems to be fairly distinctive. I posted this photo on iNaturalist, however, and haven’t had anyone confirm its identity to date.Tremella fungi had been reported from wolf lichens previously, but were thought to be “secondary” to the main symbiotic relationship. The “news” here is that these extra fungi may, in fact, be quite central to the concept we call lichens. At least in the genus Letharia. We’ll be staying tuned to new developments!

Yes, I’ve recently been getting active on iNaturalist (@slwhiteco), and am especially intrigued by checking out the lichens there. Unfortunately for me, lichen taxonomy has changed significantly since I studied them back in the Darkish Ages. Apparently the advent of DNA analysis has stimulated, or required, major revisions in groups, and I’m still trying to untangle the implications. Perhaps we’ll explore a few of them in a future post.

My other complicating factor is that I’m no longer in Colorado. The move, and preparations for it, were a significant distraction from this website, but we’ll hope to bring you more lichen material in the future. Sadly, other than several Cladonia and some corticolous species, I’ve not found good lichen-hunting in this part of upstate New York yet.

-

California gets a State Lichen!

This month, California became the first state to designate an official State Lichen. Based on the efforts of the California Lichen Society, the state legislature approved the lichen last summer and the law was signed by Governor Jerry Brown in July, but didn’t take effect until January 1, 2016.

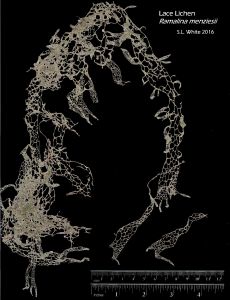

Meet Ramalina menziesii,

the Lace Lichen

Although one of several lichens that drape themselves in trees in long graceful strands, the Lace Lichen is distinctive and instantly recognizable. Unfortunately for the rest of us, this beautiful lichen occurs only along the west coast of North America. However, this makes it a perfect candidate for California’s state lichen: it is common along the coast and as much as 130 miles inland. No other lichen has the lacey or netted branches, although some species of Usnea or Alectoria appear similar from a distance.

Although one of several lichens that drape themselves in trees in long graceful strands, the Lace Lichen is distinctive and instantly recognizable. Unfortunately for the rest of us, this beautiful lichen occurs only along the west coast of North America. However, this makes it a perfect candidate for California’s state lichen: it is common along the coast and as much as 130 miles inland. No other lichen has the lacey or netted branches, although some species of Usnea or Alectoria appear similar from a distance.Learn more about Lace Lichen and its designation at the California Lichen Society webpage. But remember, it’s a lichen, not to be confused with “Spanish moss” (which is not a moss either)!

-

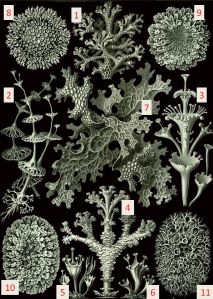

Lichens by Haeckel 1904

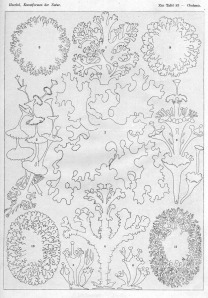

Via Wikipedia, this great illustration of “Lichenes,” drawn by Ernst Haeckel to emphasize his ideas of symmetry in his Artforms of Nature, published in 1904. Click to enlarge.

Lichenes illustration by Ernst Haeckel, labeled to match the key below. Via Wikipedia, public domain.

Haeckel’s stylized drawings convey these lichens in their most basic forms, with much of their random meandering growth reduced to precision, as evidenced in the strict circles of #8 and #9, the ovals of #10 and #11. Despite the fact that, in the field, these are apt to appear far less uniform in shape, Haeckel has captured the “personality,” if you will, of each species, making them reasonably recognizable.

Just for fun, in the key below, we’ve linked some of the species names to a current photo from other websites for comparison. Links open in a new window; use your browser’s back button to return here.

Here’s the key to these drawings, by number, with some synonymy of a more recent day added, apparently by the annotator for Wikipedia.

Here’s the key to these drawings, by number, with some synonymy of a more recent day added, apparently by the annotator for Wikipedia.

1. Cladonia retipora (Floerke) = Cladia retipora (Labill.) Nyl. (an Australian species, but here’s a photo from Pinterest)

2. Cladonia perfoliata (Hooker) = Cladonia perfoliata

3. Cladonia verticillata (Achard) = Cladonia cervicornis ssp. verticillata (Hoffm.) Ahti

4. Cladonia squamosa (Hoffmann) = Cladonia squamosa (Scop.) Hoffm.

5. Cladonia fimbriata (Fries) = Cladonia fimbriata (L.) Fr.

6. Cladonia cornucopiae (Fries) = Cladoniaceae sp.?

7. Sticta pulmonaria (Achard) = Lobaria pulmonaria (L.) Hoffm.

8. Parmelia stellaris (Fries) (non (L.) Ach.: preoccupied) = Physcia stellaris or Physcia aipolia (Ehrh. ex Humb.) Fürnr.

9. Parmelia olivacea (Achard) = Melanohalea olivacea (L.) Essl.

10. Parmelia caperata (Achard) = Flavoparmelia caperata (L.) Hale

11. Hagenia crinalis (Schleicher) = Anaptychia crinalis (Schleich.) VězdaIf you appreciate the elegance of nature, as Haeckel clearly did, you should look at this entire book. Browsing through the illustrations was like an instant review of invertebrate zoology and paleontology courses from college. Many of his drawings feature protozoans, medusoids, and other familiar lifeforms in those textbooks (if not in life); these would have enhanced some of those courses! Explore more at:

Kunstformen der Natur, Haeckel, Ernst, 1834-1919, Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig. Contributed to Biodiversity Heritage Library by University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

-

Stereocaulon, Easy to Spot

This genus is readily recognizable, but a challenge to identify to species without a microscope or chemical tests. Stereocaulon is very unusual in structure, even for a lichen. It is generally considered a fruticose lichen, but “it’s complicated.” They have been given the common name “foam lichens,” which certainly seems fitting.

These fluffy, feathery fruticose-looking lichens actually consist of a crustose primary thallus that develops a secondary thallus of branched stalks, sometimes called pseudopodetia. In most species, the crustose part of the thallus disappears, leaving no clue that this critter is anything but fruticose.

To identify species, you also need to master a specialized vocabulary. Growing on the branches of Stereocaulon are granules or squamules called phyllocladia. The phyllocladia, whether flat or coral-shaped, contain Trebouxia, a green alga commonly found as a lichen photobiont. Nestled among them we may often find structures called cephalodia (you may recall we saw these in Peltigera as well). The cephalodia contain cyanobacteria, often Nostoc.

In this closer view, no apothecia are seen. I wouldn’t call this “mat-forming, without main stems,” so that kinda rules out S. rivulorum. Options (in LoNA key) for phyllocladia are “granular to squamulose, rarely coralloid” versus “warty, sometimes lobed.” What do you think? If I had to make a wild guess, I’d say Stereocaulon glareosum, which has been reported from the area.I’d also say we need a dissecting microscope. This is why we like to talk about genera more than species! (And why we’ll maybe tackle an easier species next time!)

According to my search of collections at Lichen Portal (CNALH), in Colorado we have 15 taxa in 11 species of Stereocaulon, with some specimens not identified to species. Most of these collections are at elevations above 2400 m (8,000 ft). Our species are:

- Stereocaulon albicans

- Stereocaulon alpinum

- Stereocaulon dactylophyllum

- Stereocaulon glareosum (retains primary thallus; cephalodia brown)

- Stereocaulon glareosum var. brachyphylloides

- Stereocaulon incrustatum

- Stereocaulon microscopicum

- Stereocaulon myriocarpum

- Stereocaulon myriocarpum var. orizabae

- Stereocaulon paschale

- Stereocaulon paschale var. alpinum

- Stereocaulon rivulorum (arctic-alpine, no apothecia)

- Stereocaulon subalbicans

- Stereocaulon tomentosum (thallus erect, not matted; tomentose; apothecia common, brown and terminal; cephalodia blue-black)

- Stereocaulon tomentosum var. compactum

Of the 11 species (357 specimens identified to species), most commonly collected here are S. tomentosum (129), S. glareosum (85), S. rivulorum (69), and S. alpinum (45). Chances are this specimen is one of these four. If just going by these photos, I’d love to say it’s S. rivulorum!

Stereocaulon alpinum photo at Sharnoff Photos

Stereocaulon rivulorum photo at Sharnoff Photos

Stereocaulon tomentosum photo at Sharnoff PhotosData summarized from:

Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria (CNALH). 2014. http//:lichenportal.org/portal/index.php. Accessed on December 27. -

Lichens and Rocks

Lichens that grow on rocks are called saxicolous, and a great many species fall into this category. These are the bright splashes we see when out hiking or just enjoying the scenery. But did you know that some of them have distinct preferences in the types of rocks they grow on? Their occurrence is not haphazard; they need to find the correct substrate, and knowing the preference for a particular species can help you locate it!

Lichens that grow on rocks are called saxicolous, and a great many species fall into this category. These are the bright splashes we see when out hiking or just enjoying the scenery. But did you know that some of them have distinct preferences in the types of rocks they grow on? Their occurrence is not haphazard; they need to find the correct substrate, and knowing the preference for a particular species can help you locate it!Substrate Specificity

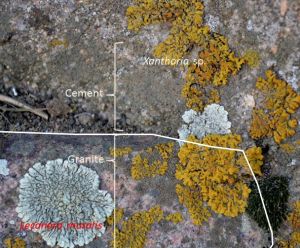

The preference of lichens for a particular rock type can be based on chemistry: is the rock basic or acidic? Limestones, which are relatively sparse in our area, often support lichens that may not be seen elsewhere. Other species will be found on sandstones or the granitic or metamorphic rocks of our mountain areas. The cement of sandstones can be either calcareous (basic) or siliceous (acidic), which determines which lichens it will support.

For example, Xanthoparmelia species will generally be found on siliceous rock types, and thus are common in the granitic or metamorphic substrates so abundant in the Rocky Mountains and other places where igneous or metamorphic rocks dominate.

Bright orange Xanthoria elegans responds to environments high in nitrogen, and can often be seen in broad swaths below bird or rodent perches.

Bright orange Xanthoria (probably X. elegans) grows in channels where nutrients are washed down from animal perches. Fountain Sandstone, S.L. White.

Lecanora muralis, a cosmopolitan species across the U.S., occurs on various rock types, also likes nitrogen, and often colonizes cement and mortar because of their high calcareous content. Because it appears on manmade surfaces, it has been called “stonewall” lichen (in fact, muralis is Latin for “of the wall.”) On the stone wall in my backyard, however, it appears equally happy on the granite cobbles as on the adjacent cement.Lichens and Weathering

Lichens also help break down rock, as we learned when we were young. Their chemical and physical interaction with the substrate on which they grow can be significant. Crustose lichens, in particular, closely interact with their substrate and are so abundant they play a significant role in weathering processes.

On this boulder of Fountain Sandstone, lichens are assisting in the weathering of the rock by exfoliation, or spalling. Photo by S.L. White.

Direct penetration of rhizines, in the case of foliose lichens, or medullary hyphae in crustose lichens may physically fracture rock surfaces. Once imbedded within a rock, expansion and contraction of lichen thalli with changes in temperature and hydration status will contribute to the pressures that result in surface disintegration of rocks. —Nash et al., page 153

-

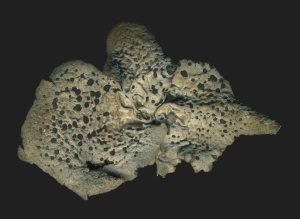

Umbilicaria, or Rock Tripe

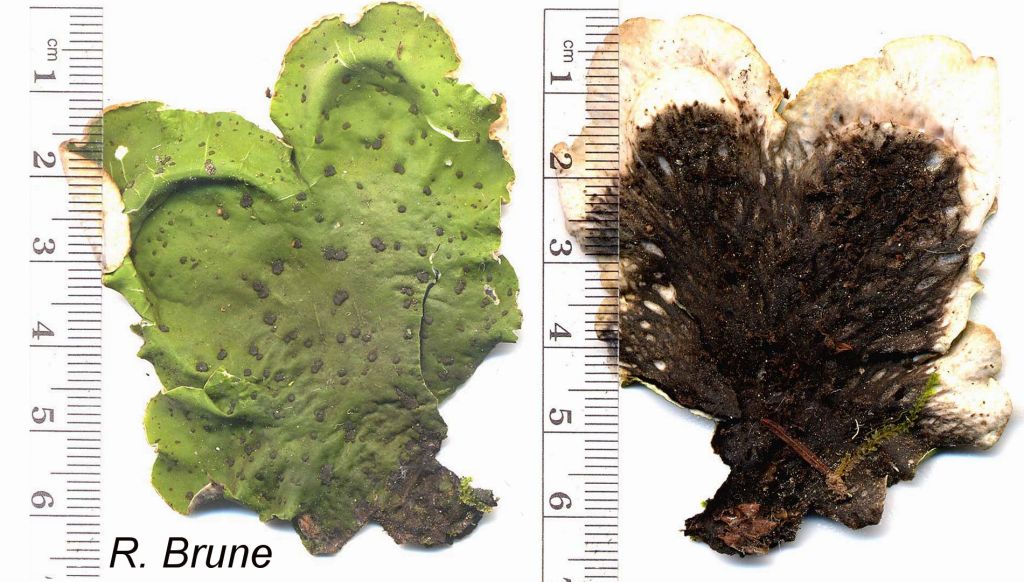

Umbilicaria americana, FROSTED ROCK TRIPE

Umbilicaria americana, FROSTED ROCK TRIPE

This species and its relatives are known as “rock tripe” and said to be edible, though perhaps only in dire situations. For example, the related species Umbilicaria mammulata reportedly fed George Washington and his starving troops during the harsh winter of 1777 at Valley Forge. A distinctive and abundant lichen on moist, vertical cliff faces in the Front Range, it lacks apothecia and has a sooty black underside covered with rhizines, creating a velvety appearance. Thalli are leathery (and green!) when wet, and are “umbilicate” (attached only at one central point); they can be 15 cm across. Largest and most notable of our umbilicate species, this often grows in huge colonies.Fun fact: Some species of Umbilicaria have intriguing black “gyrose” apothecia with concentric fissures. This species, however, is rarely seen with apothecia.

Thalli are leathery (and green!) when wet, and are “umbilicate” (attached only at one central point); they can be 15 cm across. Largest and most notable of our umbilicate species, this often grows in huge colonies.Fun fact: Some species of Umbilicaria have intriguing black “gyrose” apothecia with concentric fissures. This species, however, is rarely seen with apothecia.

Another large species of Umbilicaria, this brownish one with abundant black apothecia and a more wrinkled upper cortex. Perhaps U. hyperborea.

Don’t be fooled: Umbilicaria vellea is similar, but usually smaller and generally found at higher elevations or latitudes. Details of the rhizines distinguish the two.

-

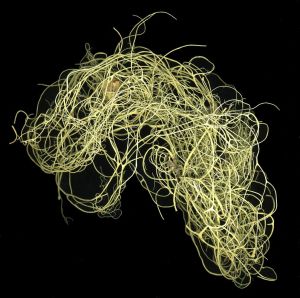

Old Man’s Beard, the Genus Usnea

Some fruticose lichens form long webs, dangling from tree branches, that acquire common names like “tree hair” or “old man’s beard,” especially in places like the Pacific Northwest, where high humidity and tall trees support their robust expression. From a distance, these resemble the “Spanish moss” of southern states (which is neither moss nor lichen).

Long pendulous thallus of Usnea cavernosa, found on conifers in Rocky Mountain National Park, the San Juan Mountains, and other high elevations in Colorado. Not common here; this scan is of a specimen from Idaho.

More common in our Colorado forests are species of Usnea that display themselves less dramatically. Most are no more than a few inches tall (or long) and are frequently seen on bark of conifers like Douglas-fir and Colorado or Engelmann spruce. (Oddly, however, not on ponderosa pine.)

Common species of Usnea, such as U. hirta and U. subfloridana, occur on conifer bark and are small and shrubby. At higher elevations with adequate moisture, larger species like U. cavernosa (at top) may be seen.

A closer view of this same specimen is below; click to enlarge further.

A close-up of the same lichen shows the tangled branches characteristic of the Usnea thallus. Each branch has a tough central cord, which distinguishes this genus from other light-green arboreal genera, like Evernia and Ramalina.

Detailed description of Usnea cavernosa

More Usnea photos (at Ways of Enlichenment)

List of Usnea species and photos (at Sharnoff Lichens) -

Peltigera leucophlebia

Or is it Peltigera aphthosa? Only by peeking underneath can you be sure! This post was published as a lichen profile in the Winter 2013 issue of Aquilegia, newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society (Vol 37, No. 6). Back issues are available online at the CoNPS website..

Peltigera leucophlebia, Peltigera aphthosa

Broad, ruffled lobes would place the abundant “pelt” lichens among the most noticeable of our montane lichens, were it not for their usual cryptic brown and gray coloring. Fortunately three of our 15 species stand out, at least when wet, thanks to the chlorophytes that are their primary photobionts. Peltigera aphthosa and Peltigera leucophlebia (clear veins) are large lichens with bright green coloring that helps us spot them when the forest floor is moist. The 2-4 cm wide lobes radiate to form a thallus 30 cm or more across.

To distinguish these two species, you’ll probably have to take a peek at the underside. P. leucophlebia, as its name implies, has distinct veins that change from light colored near the margin to black toward the center. Carefully loosen the lichen from the soil or mosses to check for this. In P. aphthosa, the veins tend to be broad and undefined. The uplifted lobes bearing brownish apothecia have, in P. aphthosa, green cortex on the underside of these reproductive structures, but in P. leucophlebia, the cortex is absent or present only as green specks on the white background.

Fun fact: Round dark structures on the upper surface, called cephalodia, contain cyanobacteria, giving these lichens claim to a three-kingdom symbiosis.

Don’t be fooled: Species of Sticta look like Peltigera and are in the same family, but the underside is black with white spots instead of the characteristic veins. Our third green Peltigera, P. venosa, is smaller (less than 2 cm diameter) and each fan-shaped thallus consists of a single lobe, usually with black marginal apothecia.

-

Exploring our lichen world

Several of us took a field trip yesterday to look at lichens and specifically to find lichens that were especially interesting and unusual. We succeeded completely! In our group was a new member of the Native Plant Society who had an interest in learning more about and photographing lichens, mosses, and other often overlooked small beings that we find in nature. His interest and talent have me spending time with the books again, refreshing all the things I used to know and picking up a few new ones in the process. He’s also promised to share his photos on this website soon.

Right before a sad mishap with my brand new camera, I caught this picture:

This lovely Peltigera aphthosa (or maybe P. leucophlebia) was not the most exciting lichen we saw all day, but it was the best, and pretty much the only, photo I captured. Being out looking at lichens means hope for an updated website here, but having a new photographer on board brings the certainty of MUCH better pictures! Stay tuned…

Colorado Lichens and Friends

speaking of lichens mostly, sometimes mosses and other cryptogams