A Gallery of images of the Fungi of China collection

Our art/science exhibit was displayed in Cornell’s Mann Library during the Summer of 2005. That’s about when we initiated the project of repatriating parts of this historically important collection. Images by Kent Loeffler, emeritus photographer, Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology. Text by Kathie T. Hodge, Director, Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium. © Cornell University.

Learn more: CUP and the Fungi of China and Cornell Chronicle article Cornell returns collection of rare fungi to China.

Exobasidium sawadae

This species of Exobasidium mummifies the berries of cinnamon shrubs to produce spores. Other Exobasidium species are berry mimics: they can cause blue-green leaf galls, called “fool’s huckleberries,” that are perfectly edible.

Puccinia agropyri

Rust fungi like this one have more complex life cycles than most other kinds of organisms. Many rusts infect two different hosts—wheat and barberry, for example—and have up to five kinds of fruiting bodies.

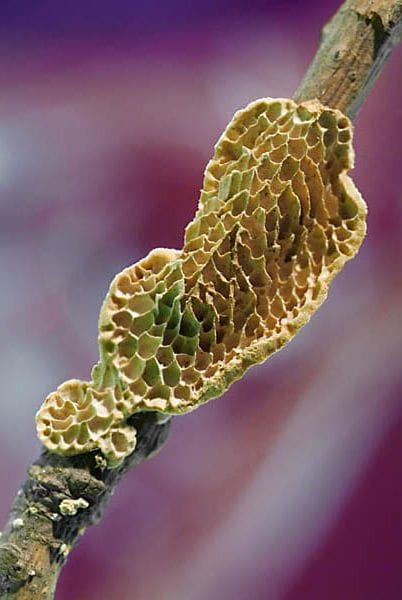

Coriolopsis phaea

Cornell scientists have been studying fungi for five generations. As in S.C. Teng’s time, scholars come from all over the world to study mycology here. Cornell has trained more mycologists than any other institution in North America.

Shiraia bambusicola

Even disease-causing fungi play an important role in ecosystems by killing some plants and sparing others. Imagine a forest in which every seedling lived to mature into a full-sized tree. There would be no room for tree-huggers to spread their arms.

Lenzites albida var. serpens

Herbaria, such as the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium, are biological libraries. Instead of books, they collect plant and fungus specimens such as this small bracket fungus. Unlike book libraries, every holding in an herbarium is unique and seldom is duplicated at any other institution.

Trametes cinnabarina

Mycophobia, the fear of fungi, has deep roots in Western culture. Despite their unpopular reputations, fungi can be appreciated for their strange beauty and for their essential roles in the environment we share with them.

Coccostroma arundinariae

Japanese mycologist Kanesuke Hara first named this fungus for its host, a bamboo in the genus Arundinaria. Later, S.C. Teng assigned this species to the fungal genus Coccostromopsis—and still later, to Coccostroma—reflecting a better understanding of the relationships among fungi.

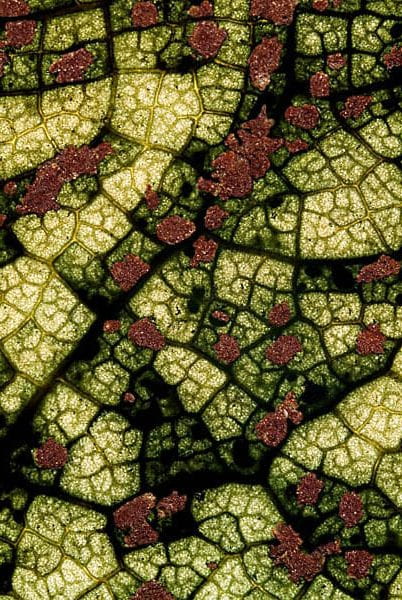

Puccinia angelicaeedulis

On this leaf, the stained-glass effect is produced by the light and dark green interveinal areas interspersed with the tiny, red fruiting bodies of a rust fungus. Spores from the fruiting bodies will be carried by the wind to infect new hosts.

Aecidium osmanthi

These blemishes on a fern may seem insignificant in the larger scheme of things. But other plant-pathogenic fungi have influenced human survival since agriculture was invented.

Phellinus pini

This bracket fungus supports a sunbathing passenger—a lichen taking advantage of a platform for photosynthesis. Sometimes mistaken for true plants, lichens actually are symbiotic partnerships between fungi and algae and grow in places where neither partner could survive alone.

Cucurbitaria pithyophila

More than 250,000 species of fungi have been described. Yet, mycologists think this represents less than 10 percent of the species that exist on Earth. Fungal biodiversity is one of the great frontiers of scientific exploration.

Hymenochaete mougeotii

Many of the undiscovered fungi are probably overlooked because they are so small or because they don’t cause “trouble” for humans. Others wait to be discovered in places where mycologists rarely visit.

Pulcherricium caeruleum

Fungi come in virtually every color of the rainbow (for example, this blue velvet fungus), but we know little about the role of coloration in fungal life histories. Nevertheless, fungal pigments have been important for mankind. For example, Harris tweed is dyed with natural pigments derived from lichens.

Lentinus tigrinus

These fungi grow on rotting logs and have incredibly tough fruiting bodies. Fungi are the most important decomposers of fallen trees, having a special aptitude for digesting cellulose and lignin.

Cordyceps myrmecophila

Although fungi cause few important diseases in humans, more than a thousand species specialize in killing and eating insects. This ant died after being invaded by a fungal spore, which went on to produce a macabre, thread-like fruiting body.

Tylopilus balouii

Eastern North America and eastern China share a curious floristic bond. This wizened specimen—an edible mushroom commonly called Ballou’s bolete—was collected in China, but the species was first described from Long Island, New York.

Ganoderma lucidum

Many fungi are used medicinally in China. This fungus, also known as Ling-Zhi, the fungus of immortality, is said to confer wisdom, health, sexual prowess, and happiness. Modern studies have borne out some of its healing effects.

Ustilago hordei

Even before the dawn of agriculture, humans have had to compete with fungi for food. Here, the nutritious kernels of barley have been completely replaced by the powdery black spores of U. hordei.

Trametes hirsuta

At Cornell, fungi are collected at a unit of the Department of Plant Pathology. More than 80 percent of plant diseases are caused by fungi. The remainder are blamed on bacteria, viruses, nematodes, spirochaetes, and phytoplasmas. This bracket fungus probably contributed to the demise of a tree.

Polyporus elegans

Fungal fruiting bodies are just the tip of the iceberg. They arise from an extensive but unseen network of mycelium, the cells of which are finer than spider’s web. The mycelium of this fungus grew within the sapwood of a tree.