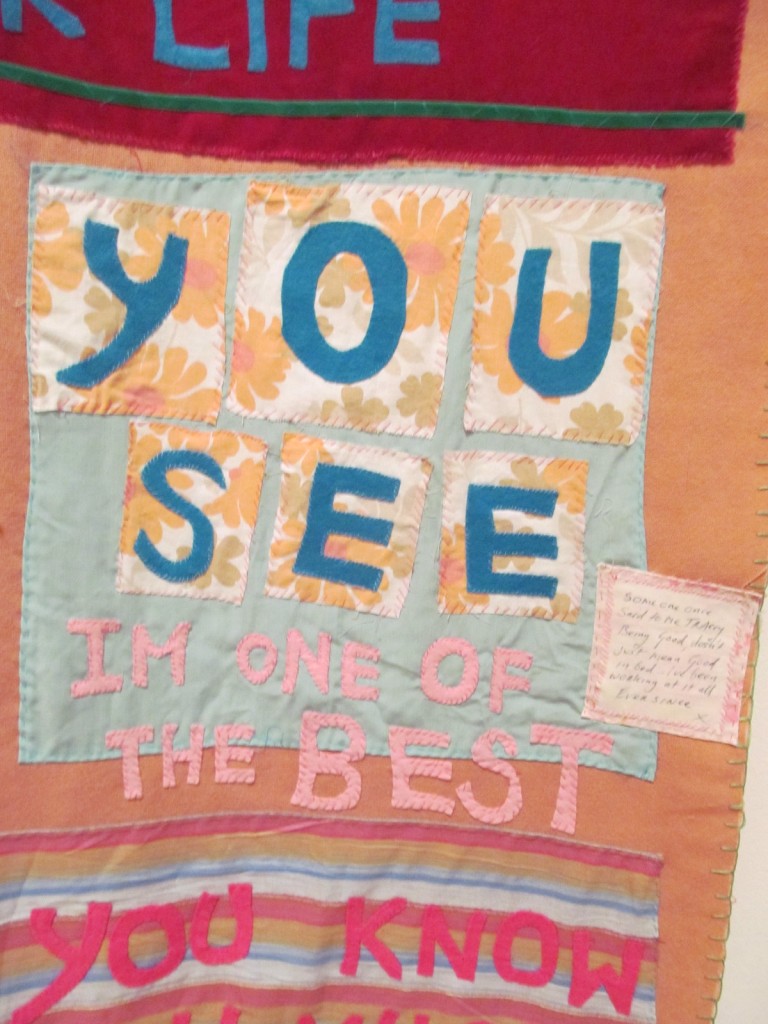

Text in artwork is, unfortunately, often divorced from its literary heritage. By treating text in artwork as if it belongs solely to the discipline of the visual, we can only build one dimensional critique of such artworks that, in fact, build on multiple loci of meaning. Chris Townsend remarks that the text in Tracey Emin’s Mad Tracey From Margate, Everyone’s Been There (1997) comes across as ‘effected by someone barely capable of coherent writing, and therefore, we assume, barely capable of cogent thought.’[i] However, if we take it in the context of her biography, and therefore her oeuvre, we should consider that her textual ‘mistakes’ are not so accidental, nor necessarily building a persona of someone struggling with cogency. The incorrectly formed ‘N’, the lost and hovering apostrophe of ‘weve’, and the misspelling of ‘weak world’ as ‘week world’, all suggest a rushing and racing mind that has no time for correct language. However, when we consider the medium of the work, the time and contemplation the artist must put into deliberately cutting out each letter and grammatical mark, the reading of an implied state of ‘barely cogent thought’ cannot hold. Instead, it seems to emphasise the handmade aspect of the work and, therefore, the intimacy of the words. These are not mistakes or misspellings, but self-assertions of the artist’s knowledge against an institutional definition of what is correct or incorrect language.

Emin herself says that ‘I try to put the word down, but if I don’t know it I don’t care.’[ii] Her misspellings are not on purpose, but that they are permitted. Rather than creating a sense of psychological instability, the language emphasises the elements of simultaneity in the text by presenting the collection of words as ‘unmediated utterance,’[iii] while also highlighting the reflexive autobiography of the artwork through its time consuming and deliberate medium. The words are not incorrect because they are not misspelled by accident. Emin challenges the linguistic system’s restraints by refusing to censor or ‘correct’ her writing so that her expression conforms to grammatical law, therefore she asserts and prioritises her own expression over a standard model of art or language. Emin produces ‘not a work of art for the sake of art, but for the sake of the progenitor.’[iv] Her work cannot be anonymised in the mainstream of modern art practice as it is so fundamentally and intimately linked to the artist. Emin shows us how the use of language can contribute artistically to the presentation of a breakdown of power structures. By supporting the ‘incorrect’ use of needlework with the ‘incorrect’ use of language, Emin complexly presents a narrative of dysfunctionality in childhood. However, without in-depth analysis of the literary heritage and form of the text, our understanding can still only be one dimensional.

Image Credit: Rob Corder

Image Credit: Rob Corder

Tracey Emin’s needlework writing follows Hélène Cixous’s behest to create new forms of writing to avoid ‘the imbecilic capitalist machinery’ of publishing.[v] By creating literature through needlework, Emin uses a traditionally feminine craft to disrupt traditional forms of literature and express herself through an uncensored voice. Brown explains that ‘Emin’s highly poeticised, textual confessionalism has enjoyed favour during a period when much poetry has withdrawn into what often seems a cautious shyness.’[vi] As a literary academic, I naturally disagree with Brown’s generalisation of poetry being withdrawn in a moment concurrent to Carol Ann Duffy, Kae Tempest, and Claudia Rankine. However, I do believe that Emin’s ‘textual confessionalism’ is enabled by the pre-existing form of Confessional poetry. Although hotly debated, the term Confessional poetry typically refers to poetry written in the mid-late twentieth century that adopts a personal voice, colloquial style, and pulls from biography for inspiration. Poets such as Ann Sexton, Robert Lowell, and Sylvia Plath ‘exposed the family as a crucible of trauma, a site of emotional warfare that shapes the self, and frequently delved into the psychic wounds of childhood to uncover the secrets of adult distress’. By yoking the poetic genre to a disruptive use of language and domestic craft, Emin’s applique work builds meaning that is both personal and political.

Rather than needing to create her own form because of poetry’s ineptitude, she actually creates an art object out of an already established poetic trend. Both the Confessional poets and Emin write of their lives in ‘the candid examination of what were at the time of writing virtually unmentionable kinds of private distress.’[vii] In fact, Emin began her artistic career by selling literature, writing commissioned letters about her private life to subscribers for £10.[viii] By consider her literary points of origin, we may be able to garner more meaning from her work. For example, if we look at Sylvia Plath’s work in comparison to Emin’s Hotel International (1997) we see some striking similarities. Hotel International is named after the hotel in Margate that her mother ran at the time and that she and her brother lived in. It mentions the KFC that acted as her childhood hang out, along with memories of trips with her father to Cyprus and Istanbul.[ix] The quilt becomes a collage of nostalgia and somewhat of a goodbye to her childhood. Displaying the words ‘Hotel International the perfect place to grow’ at the very bottom gives the recollections scattered throughout the piece a sort of mythic element. Her and her family were, in fact, squatting in the hotel for a while after it had shut down, and so it makes sense that she writes in her memoir that her childhood was often so tumultuous that ‘I had never known the truth, so I had never cared for the truth, rationality or reason. I lived in a world of dreams, good and bad.’[x] Hotel International weaves fragments of a complex childhood into a stable narrative that can be interpreted through a singular object, an approach to biography often seen in the Confessional poets’ use of extended metaphor.

Emin says that art language is often restrictive, ‘Everything’s covered with some kind of politeness, continually, and especially in art because art is often meant for a privileged class.’ Therefore, if we were to truly consider Emin’s language as low brow in contrast to the art context, we would be wholly missing the point. Townsend wrote that Emin was ‘barely capable of coherent writing’, however, I would argue that she asserts self-expression over the inaccessibility of Art English. Emin uses accessible language and familiar domestic material to overcome pretence while aligning her work with the tradition of Confessional poetry to ensure that the text comes across as meaningful rather than simply ‘incoherent’. By forming a critique of textual artwork that accounts for its position at an intersection of disciplines, we can find meaning where we would otherwise see inarticulate scrawl.

[i] The Art of Tracey Emin, ed. by Mandy Merck and Chris Townsend (New York, N.Y: Thames & Hudson, 2002), p. 84.

[ii] Merck and Townsend, p. 202.

[iii] Neal Brown, Tracey Emin, Modern Artists (London: Tate Publishing, 2006), p. 61.

[iv] Merck and Townsend, p. 60.

[v] Hélène Cixous, ‘“The Laugh of the Medusa”: New French Feminisms’, in Feminist Literary Theory: A Reader, ed. by Mary Eagleton, 2nd ed (Oxford,UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), pp. 320–22 (p. 323).

[vi] Brown, p. 61.

[vii] Chris Baldick, ‘Confessional Poetry’, The Oxford English Dictionary of Literary Terms (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[viii] Will Gompertz, What Are You Looking At? 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye (London: Penguin, 2016), p. 381.

[ix] Tracey Emin, Strangeland (London: Sceptre, 2005).

[x] Emin, p. 15.

[xi] Sylvia Plath and Frieda Hughes, Ariel: The Restored Edition; A Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement, Paperback ed (London: Faber and Faber, 2007), p. 74.

[xii] Dan Duray, ‘Emin-Ence Gris: Tracey Emin Comes to America’, Observer, 2013 <https://observer.com/2013/05/emin-ence-gris-tracey-emin-comes-to-america/> [accessed 31 August 2019].

[xiii] Stuart Morgan, ‘The Story of I’, Frieze, 1997, pp. 58–60 (p. 60).

[xiv] Alix Rule and David Levine, ‘International Art English’, Triple Canopy <https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/international_art_english> [accessed 12 September 2019].

Bibliography

Baldick, Chris, ‘Confessional Poetry’, The Oxford English Dictionary of Literary Terms (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015)

Brown, Neal, Tracey Emin, Modern Artists (London: Tate Publishing, 2006)

Cixous, Hélène, ‘“The Laugh of the Medusa”: New French Feminisms’, in Feminist Literary Theory: A Reader, ed. by Mary Eagleton, 2nd ed (Oxford,UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), pp. 320–22

Duray, Dan, ‘Emin-Ence Gris: Tracey Emin Comes to America’, Observer, 2013 <https://observer.com/2013/05/emin-ence-gris-tracey-emin-comes-to-america/> [accessed 31 August 2019]

Emin, Tracey, Strangeland (London: Sceptre, 2005)

Epstein, Andrew, The Cambridge Introduction to American Poetry Since 1945 (Cambridge ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2023)

Gompertz, Will, What Are You Looking At? 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye (London: Penguin, 2016)

Merck, Mandy, and Chris Townsend, eds., The Art of Tracey Emin (New York, N.Y: Thames & Hudson, 2002)

Morgan, Stuart, ‘The Story of I’, Frieze, 1997, pp. 58–60

Plath, Sylvia, and Frieda Hughes, Ariel: The Restored Edition; A Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement, Paperback ed (London: Faber and Faber, 2007)

Rule, Alix, and David Levine, ‘International Art English’, Triple Canopy <https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/international_art_english> [accessed 12 September 2019]

Words: Isaac Fravashi

Biography: Isaac Fravashi is a writer, artist, and researcher at the University of Southampton. He is working on a PhD exploring collage and gender in contemporary art and poetry. Isaac spends most of his time climbing, stroking his cat (Shira), and working on his thesis. He can be found in many places through the username @eyeszac