Julian Opie – Artist Review

Julian Opie may not be a household name, yet most will recognise his cover art for Blur’s Best Of album. Opie updates and animates many classical Fine-Art genres. Andy Warhol’s “pop art” influence is all over Opie’s work, especially in his silk/screen aesthetic. The LED screens are much more engaging with the galloping horse, clearly inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s stop action photographs, having an hypnotic effect.

Opie is less known for his video works of living landscapes but there are plenty on display at this exhibition. With the addition of ambient insect noises they have the potential to be fully immersive but when there are four in the same room they manage to drown each other out.

Opie, with his LED moving frames makes reference to an age where photography was still a scientific tool. Think of Eadweard Muybridge and his First Motion Picture Horse of 1878, which showed the world how the horse actually propelled itself on the ground (a phenomenon that was too fast for the eye to see before this point). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrRUDS1xbNs.

There can be few artists who seem as fresh in their work as Julian Opie. The faceless figures are so vivid in their vinyl, the landscapes so clear in their block colour. But there is also a feeling of distance which has come into his work of late, a sense of growing detachment from the work itself, the inhumanity of technology he uses.

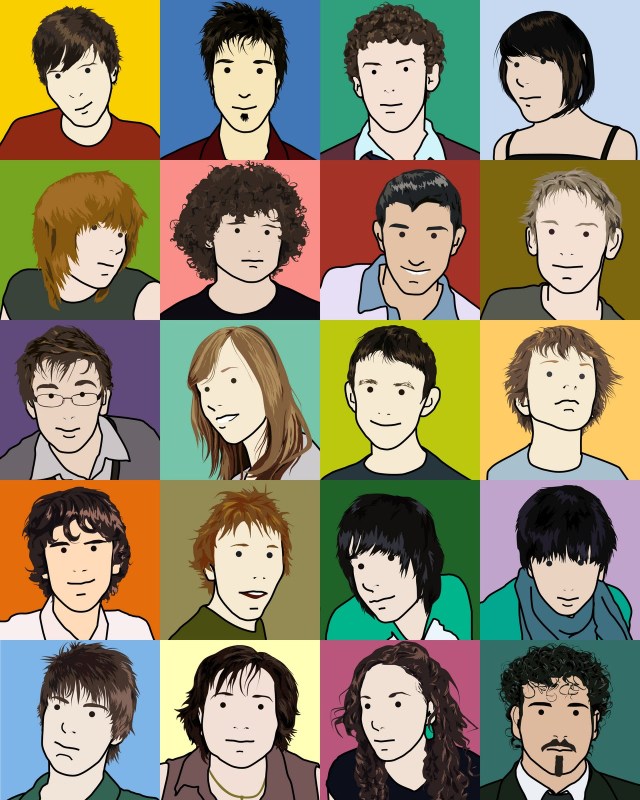

Maybe it is to read too much in the feeling, or lack of it, in his figuration. Opie, now in his mid 50s, is above all an artist of form, ever eager to pick up the latest technology and the new materials to recast the traditional genres of painting. He brings these new technologies to all of the work he does be it computer animations, mosaics, the inkjet on canvas and the scanned resin busts. So, too, are his long-standing themes: the walking people, the nudes of his wife, the portraits of society women and the heads of his assistants and his family.

With the full-length portraits he has turned from facial feature to fabric effect. In the manner of Ingres he portrays his sitters clad in fashionable frocks standing by pillars and classical urns. The faces are blank but the gowns are done with panache. In a way it is every society woman’s dream – to be presented in their finery but not with their wrinkles. One might wish for a little wit (although the works are not without a certain wry humour). Cindy Sherman would, and has, made something quite else of such neoclassical figures. But they are remarkably effective in their blend of classical majesty and modern self adornment.

The classical setting is maintained in the main room of the exhibition, which Opie has deliberately organized in the manner of a museum gallery, with rows of busts, a line of walking figures on the wall, a grouping of mosaics at the entrance and standing works in the middle. It is an impressive sight. The busts, cast in resin, have been made from digital scans of his subjects and then hand-painted, all with one side of the face shadowed, all staring into space like the funerary busts of the Roman world. The mosaic portraits – a fairly recent development in Opie’s art – are equally shadowed with the colour range and graduation limited by the medium (they have been made in Rome).

The standing works also owe much to Greece and Rome. The artist’s wife is depicted in enamel on glass, disrobed in the manner of the Greek Venuses. Outlined figures are inscribed on granite and marble looking like massive sarcophagus lids. With his emblematic walking figures, Opie has moved out of the studio into the city streets to photograph anonymous Londoners at work, reflecting the figures in vinyl on wooden stretcher. They are arranged in a line on the wall as a modern version of Egyptian and Assyrian friezes, only Opie’s figures stride in different directions, their faces blank as they go their hurried way. Just as in ancient friezes they are symbolic in their anonymity, yet in their colour and movement they are also very real.

The total effect of this figurative work is intentionally sculptural but also funereal. Opie is a master of the materials and imagery of billboard simplification. It gives his figures a brashness and an energy that belies pomposity. Yet, save in the openly erotic disrobed figures, his search for a statuesque style sets the viewer at a distance. The sitters are real enough and the walking figures drawn from contemporary life. Yet you feel that you are looking at people already of the past and depersonalised. They are captured and pared down, not lovingly delineated.

No such feelings arise with Opie’s landscapes and computer animations. It may be unfortunate that the show has come so soon after David Hockney made such a splash with his Yorkshire landscapes at the Royal Academy. Opie uses some of the same techniques of digital sketching and screen presentation. But his views of France, where he has a house, have a more elegiac feel than Hockney’s bursting ambition to take hold of landscapes and own them.

A series consisting of over 70 digital sketches, based on images taken every 20 steps on circular walks with his son, view the countryside in summer and in winter. The images click down to the sound of music specially commissioned from Paul Englishby, adding to the elegiac tone. It would be pretentious (well, it is a bit) if it wasn’t for the simplicity of the forms and the purity of their colour.

Taking his inspiration from Japanese landscape prints, of which he is something of a connoisseur, Opie has also moved from his first more imitative versions of Hiroshige to computer animations, in which images of trees and flowers are presented on a vertical screen, enlivened by insects and other effects randomly animated by a computer program. Opie, in his way of updating the classics, has played a major role in Fine-Arts transition into new media.