Writer Peter Milligan, illustrator Brendan McCarthy, colourist Carol Swain

It’s not often that a comic book story gets you in the chest, but Skin did me. When I was a small boy in the late 70s I lived in Kilburn, London and my best friend was a skinhead named Anthony. Even though he was only eight at the time I was impressed by how popular he was with the older girls and although I never became a skinhead myself I was often hanging out with him, which meant trespassing around dilapidated buildings, being chased by older boys with their dogs for being in the wrong place, fooling around with girls our age in abandoned cars, and listening to his brother’s ska records whilst looking out of the windows across the tower estates. So reading Skin brought back a lot of memories.

Skin was originally going to be serialised in 1990 in the British comic, Crisis, but their printers refused to handle it due to its content and, following legal advice, Crisis’s publishers, Fleetway, decided they couldn’t go ahead. It’s a shame because Peter Milligan’s and Brendan McCarthy’s uncompromising story about the effects that the drug Thalidomide have on a young skinhead called Martin is probably the best story that Crisis ever commissioned. A couple of years after Skin was dropped by Fleetway, and following a number of other publishers who had initially shown interest ultimately getting cold feet, Milligan and McCarthy finally succeeded in finding a publisher – the UK division of Tundra which was headed by ex-Deadline editor, Dave Elliott – and it was released as a graphic novel. The feared controversy never materialised.

Skin, Tundra — 5/5

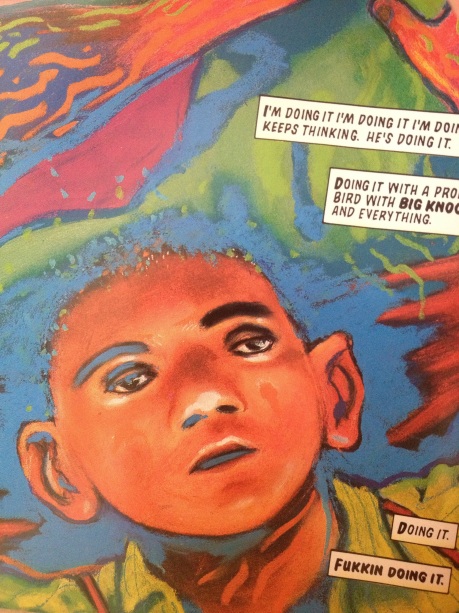

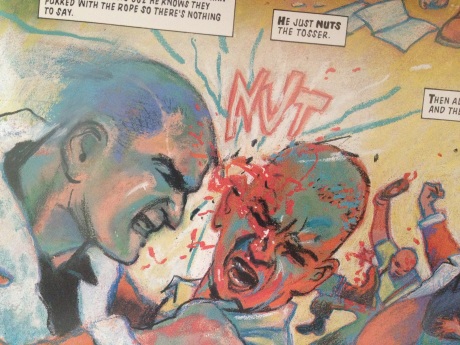

The story is about an adolescent skinhead born with short arms, a disfigurement caused by the Thalidomide that his mother had taken during pregnancy, and we see the anger and frustration that he feels as he tries to lose his virginity and generally get up to all the things that his mates effortlessly get up to. It’s narrated by a friend of his and the language is that of rebellion and disaffection – you get the most from the script by mentally reading it in his tone and accent – and both Milligan and McCarthy were skinheads when they were younger so the language and attitude sound authentic. McCarthy’s drawings are vibrantly coloured by artist Carol Swain and it’s difficult to tell where his art finishes and hers begins. Instead of using a rigid panel structure, the images are arranged like a memory or hallucination, with tangents to the main story appearing within larger compositions and colours from one scene bleeding into the next – it’s very effective and the colours have a trippy fluidity and an explosive violence all of their own. It’s obvious why so many people felt uncomfortable with Skin at the time – aside from the language, the violence meted out to Martin’s victims is extreme, but no more so than what was regularly seen in mainstream violent cinema. Perhaps the real reason that people found/find the story disturbing is because it’s so wholly honest and truthful – sometimes raw honesty is not the easiest thing to be confronted by when you can’t immediately empathise with a situation that at first glance seems totally different to your own. You could think of Skin as a brave work that dared to tackle an uncomfortable issue that affected a tiny minority of people, but personally I prefer to think of its depictions of alienation, peer pressure and life-fuckery at the hands of irresponsible corporations as universal themes that speak to everyone.

MS