Day 25 – Donatello, The Resurrection, c. 1460-65, San Lorenzo, Florence.

Happy Easter! And to celebrate: my favourite image of ‘The Resurrection’. Why this one, of all the possible examples? Quite simply, because it’s not easy: this is a hard won victory. And because it breaks all the rules.

Most versions of the Resurrection make it look effortless. Jesus springs forth without a care in the world, just like all good comic book escapes: ‘in one bound he was free’. Here again is Andrea Bonaiuti’s version, which I ended with yesterday (#POTD 24).

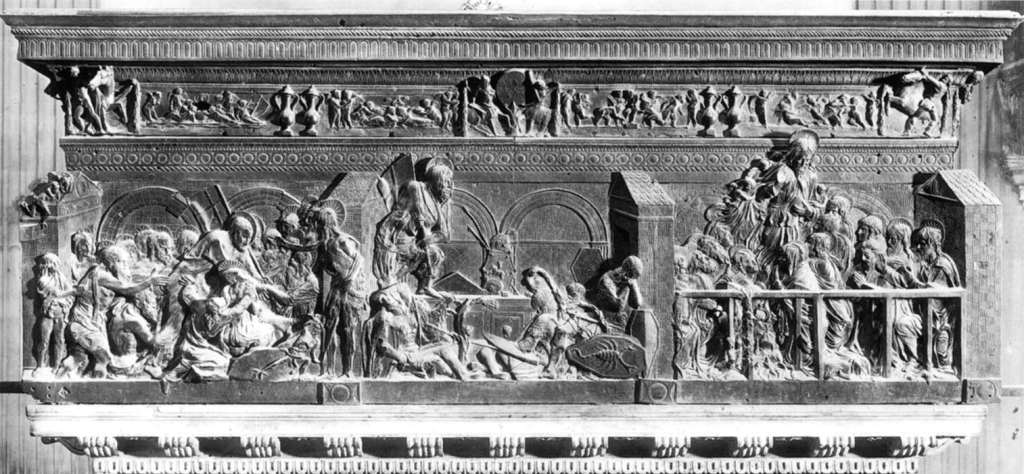

Two angels sit serenely on either side of the empty tomb, the soldiers sleep just as serenely on the floor, while the lid of the tomb looks as if it has toppled off, and is now lying where it fell, just behind the sarcophagus. Jesus floats effortlessly in the sky, the Flag of Christ Triumphant over his shoulder: it’s a red cross on a white background. No, he wasn’t English – but I’ll tell you about that another day. In other examples, the Resurrection is more explosive, with fragments of tomb flying in all directions. In yet more, Jesus appears above the still-closed tomb, apparently without even lifting the lid or disturbing its structure. Donatello sees it differently. This is hard work. He drags himself out, one foot on the edge of the tomb, grasping the standard with both hands as if he is going to use it to push himself up in that one final effort to escape the horrors of hell. He is still almost entirely wrapped in his shroud. Look back again at the Bonaiuti: as so often the shroud has been nonchalantly thrown round his shoulders as an improvised toga. For Donatello it clings to his limbs, wraps tight around his face, and slips off the shoulder with no hint of sensuality and every sign of inconvenience. And his face – this is the face of exhaustion – the face of someone at the end of their abilities. The suffering he asked his Father to free him from in the Garden of Gethsemane less than three days before is not yet over. One last push. Meanwhile, the soldiers sprawl on the ground, uncomfortable and unaware.

Like the pictures I’ve shown you over the past couple of days, it is part of a larger whole. It is just one image on a pulpit which was erected for the first time in 1515, some fifty years after Donatello died. Even then it didn’t take the form in which we see it today. There are actually two pulpits in San Lorenzo, both of which were constructed out of incomplete elements left behind at Donatello’s death in 1466. They were finished by his assistant, Bertoldo di Giovanni. If we’re honest, we don’t know what these reliefs were intended for. They are probably connected to Donatello’s great patron, Cosimo de’ Medici – not the Grand Duke of Tuscany I mentioned yesterday, but the man who cemented the power of the dynasty in the 15th Century. He was awarded the title of ‘Pater Patriae’ – Father of the Fatherland. This is the old Cosimo – Cosimo il Vecchio. He and Donatello grew old together, and, some say, they became friends. Cosimo is supposed to have commissioned work from Donatello to keep him busy in his old age, although he himself died two years before the sculptor. Cosimo was involved in a complete re-building of the local church, San Lorenzo, and was buried directly in front of the high altar. The theme of death and resurrection seen in the pulpits would be ideal for a tomb, and one suggestion is that these bronze reliefs were commissioned for Cosimo’s own funerary monument. Another suggestion is that there was a plan for the church which involved two pulpits from the outset. However, even though the pulpits have been given the same form, the shape and format of the imagery is different on each, and gaps have been made up with later work: they were not meant to be part of structures quite like this.

This scarcely matters for the consideration of this picture though. As you can see from the figure standing on the left, it is the continuation of a story – as it happens, the same story that we saw yesterday, ‘The Harrowing of Hell’ (#POTD 24). You might even recognise this figure, with his camel skin and his long, messy hair and beard: St John the Baptist.

He is reaching out to Jesus, who is struggling through the souls in hell. Working his way across the space, flag already over his shoulder, Jesus will get there. He grasps the hands of one of the souls, while others reach out to him. There is none of the orderly waiting we saw yesterday: it really is hell in here, with people reaching, grasping, striving, each with their own particular need. And Jesus keeps wading through the dead. John the Baptist reaches out to give him a helping hand, to pull him on, towards the gate on the far side of hell, opposite the one through which he entered. Donatello uses four buttresses to structure the narratives on this panel, which now makes up one side of the pulpit. There is one at either end, and two in the middle, dividing the surface into three: John the Baptist stands in front of the second from the left. These buttresses are shown in a rough perspective, as if our attention were focussed on the centre, on the Resurrection.

Going from left to right the first three buttresses all have apertures in them, presumably doors. Jesus drags his way through hell, where he will step through the door behind John the Baptist. It is from this door that he hauls himself up, out of hell and onto the sarcophagus. Or rather, he will – he hasn’t done it yet. The perspective of the buttresses is centred, and implies that the focus of the relief is in the middle of the sarcophagus, where the two arches meet. This point is marked by a trophy, made up of a shield, two spears and two helmets, the sort of trophy used, typically, in monuments celebrating a victory. Jesus hasn’t got there yet. He won’t truly triumph over death until he makes it up onto the tomb, and stands, full height, in the centre of this relief. He’s nearly there.

That’s what I love about this version: it’s so original. So unexpected. Not only that: it goes against every single idea we have about this era. The Renaissance, or at least the Early Renaissance, developed a sense of order, clarity, and balance, making images that look more like the world we live in and experience, with accurate anatomy, naturalistic scale and a measured perspective. In relief carving – or modelling like this – this was achieved by giving the foreground figures higher relief than those further back, the relief gradually getting flatter as things get further away, with some details in the background being effectively drawn in. In all cases, the space depicted is imaginary, not real. But not here! We can see this clearly in the next story that Donatello has included: the Ascension. This bit of the narrative won’t happen for another 40 days – but nevertheless, here it is.

Jesus is in a tightly crowded space, surrounded by thirteen other people. The Virgin Mary, with her head covered, is just to the right of him, and to the left of her is probably John the Evangelist: young, and beardless, with flowing hair. And the other 11? Well, the remaining Apostles, although by this stage Judas was dead. The new 12th Apostle was St Matthias, and he must be here, even though, according to the Bible, he wasn’t appointed until just after the Ascension. The figures are corralled in by a fence, which stands free of the rest of the sculpture – you can see its shadow cast on the figures behind. This isn’t imaginary space Donatello has created, this is real space, and there are far too many people crowded into it: no order, no rationale, but, instead, expression. Indeed, you wouldn’t really get anything else quite as ‘expressionistic’ as Donatello’s late style until the early 20th Century. Not only are the figures crowded too closely together, but it is also hard to see their relationship to the floor of the room. Donatello is manipulating the space, and manipulating the movement of the people in it. As they gather around Jesus, they emphasize his upward movement, while also making way so that we can see more of him, from his knees to his halo. Tiny angels help him upwards – another unprecedented feature: in most versions he can do this on his own. As it happens, he cannot leave any other way: the buttress on the far right is the only one of the four with no way out. As we saw yesterday, the only way is up.

He is so much larger than the other figures. So much for proportion and perspective! In this case, size doesn’t tell us where he is, but how important he is. Donatello has returned to a medieval hierarchy of scale, where size is equivalent to status. And not only that, on his way to Heaven, Jesus is physically leaving the picture space, head and shoulders above the frieze marking the top of the wall, his head and halo standing free from the background, solid and sculptural. Look back at the Resurrection, though: this escape from the bounds of the picture frame started there.

As Jesus progresses from left to right, from the ‘Harrowing of Hell’, through ‘The Resurrection’ to ‘The Ascension’, he gets bigger, and higher, and the relief gets increasingly deep. In ‘The Resurrection’ his head is already above the arches, with his halo in front of the circles of the frieze. And by the time he gets to the Ascension, both head and halo are clear of the frieze altogether. Jesus has left the building. Or he will do, in forty days.

In the meantime, Happy Easter! We are still in the middle of it all. Maybe we are not yet quite in the middle, we’re still waiting, but we’re getting there. It’s not easy, the last step – and who knows when the last step will be? But we will get there, and before too long we will also be able to go out. That might even be within the next forty days.

4 thoughts on “Day 25 – The Resurrection”