Herbarium History

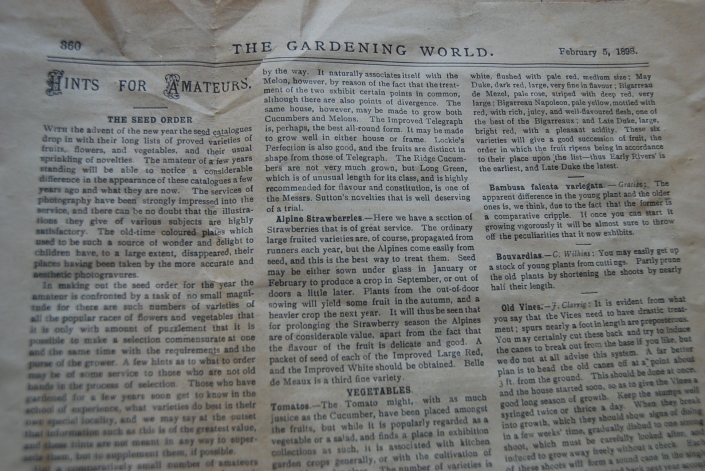

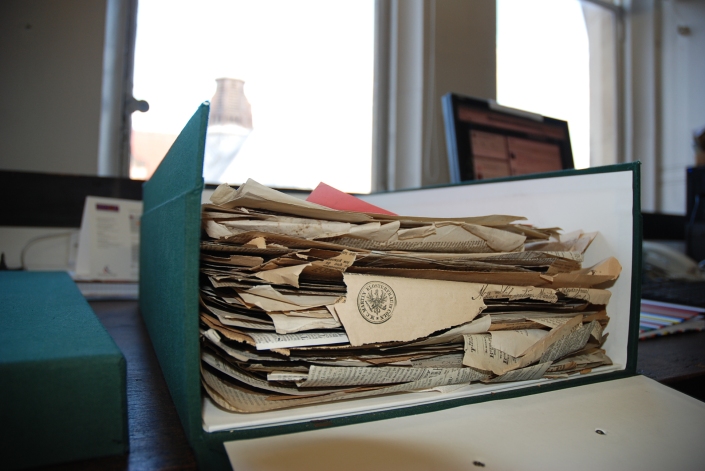

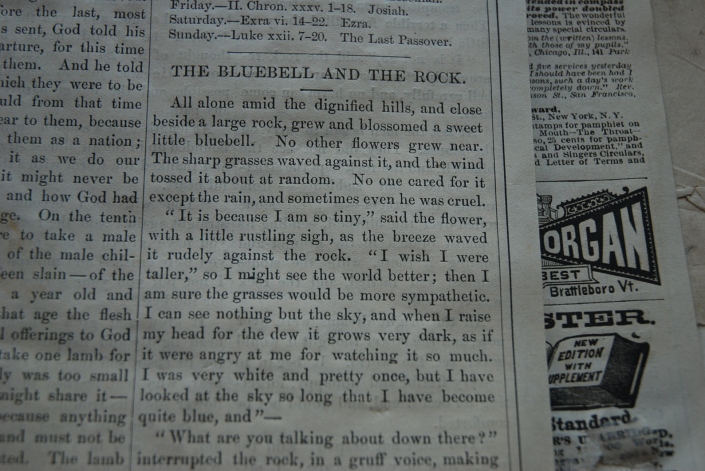

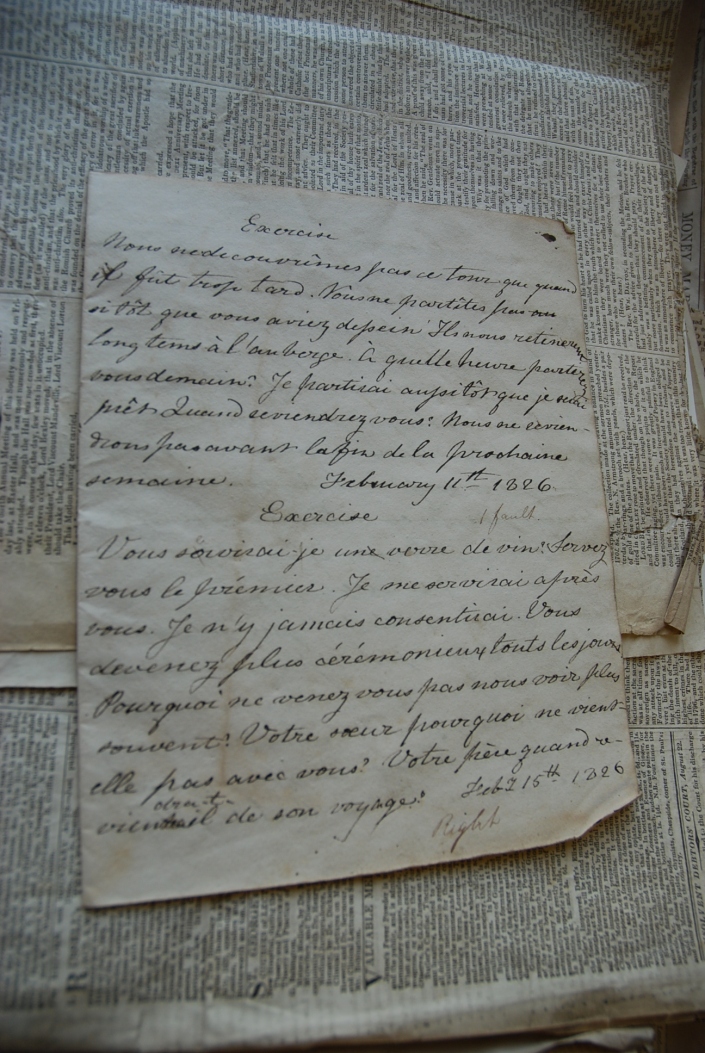

Nineteenth Century Re-Use of Newspaper

Paper was precious and expensive in the mid 19th century, when many of our herbarium specimens were collected and pressed. Some collectors re-used newspaper or letters as mounting paper for their pressed flowers.

We always keep a sheet of vintage newspaper once the plant specimen has been remounted onto new acid-free paper. Above are some of the delightful examples of adverts, stories, and articles we have discovered while working on the collection here at the Manchester Museum.

There are many more, for a future blog post.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester, News.

Internship at the Herbarium.

Hello, my name is Nicole and over the past couple of months I’ve been an intern at the Manchester Museum Herbarium. In September I’ll be going into my second year of my Neuroscience degree at the University of Manchester and I had decided to keep my summer busy and productive by gaining some valuable work experience. I can’t think of a Life Science which differs so much to Neuroscience than that of Botany, but I feel it is important to be open-minded in education and plant science is not a subject I neither have nor will encounter much due to the nature of my course.

I have been working here in the Herbarium for about 6 weeks now, thus nearing the end of my internship. I’ll be sad to leave, for it has been a fun and interesting experience working here and I have met some lovely people. It has been fascinating to see how the museum operates behind closed doors – something I would not have known without the internship.

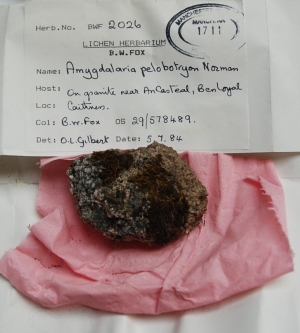

I’ve been helping both Rachel and Lindsey with photographing objects/specimens, cleaning and repairing specimen boxes, and putting specimens away. Primarily, I have been sorting through and documenting the British Lichen and Foreign Lichen collections onto the museum database. I have been recording the location of where each lichen specimen (if stated) has been found; usually converting town/county name to vice county number with the British lichens, and to country code for the foreign lichens. My geographical knowledge has improved considerably.

Lichens are organisms formed through a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and a phototroph (an organism able to make its own food from sunlight) such as algae or cyanobacteria. Symbiosis is a mutual give-and-recieve relationship between two or more biological species. The fungus provides protection and shelter to the phototroph, which repays the favour by feeding nutrients to the fungus. I was surprised at how variable the lichens are in shape and size – from flat ‘plate-like’ discs to long fibrous hairs. Lichens are valuable to the environment as they help prevent desiccation, and are good indicators of air pollution.

This entry was posted in Biodiversity, Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, Students, Trees, Uncategorized.

Perfumes from Ancient Egypt

Choosing specimens to photograph: ingredients of fragrances thought to be used by the Ancient Egyptians.

From left to right: Galbanum, cinnamon, myrrh. Front: cardamom

Photographs of these may be chosen as part of our new Ancient Worlds Gallery, opening in October 2012.

Galbanum and myrrh are both types of gum resin, which comes from small trees growing in North Africa. Both are strongly aromatic and often used in insense. Cinnamon is from the inner bark of the Cinnamomum tree.

The jars are from our Materia Medica collection. There are previous blog posts about the Materia Medica Museum at the University of Manchester, and this one has more about myrrh.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists.

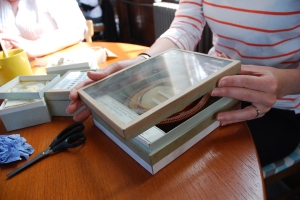

Box mending

These pale blue card boxes are probably around 150 years old – a similar age to the specimens housed inside. They are great for storage, because you can see what’s inside through the glass lid, and the specimen is protected and not squashed. Boxed specimens like these have been used in exhibitions in the past, and some are currently on our Museum Handling Tables.

However, there is a problem. The box lids are coming apart. The glue that holds the card rim around the glass to form the lid is just not sticking any more. So the glass is loose, and sometimes the card rim is torn, or even worse, completely missing!

And so, I have embarked on a programme of Box Mending, with the help of the other Curatorial Assistants in the Manchester Museum. We have several materials to help us: scissors, gummed paper tape (archival quality, of course), and most effective of all, water.

We cut the tape to the right size, moisten it, and stick it on in strips. This works well at the corners where the card is torn.

Even better, though, is moistening the 150 year old glue to reactivate it. Once held in place and allowed to dry, the ancient glue works just like new! A quick polish of the glass and the boxes are restored and functional once more.

Very satisfying!

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester.

World Museum Liverpool

It is often inspiring to visit other herbaria. To get a feel of another collection of pressed plant specimens, to discuss which acid free paper or archival quality glue should be used, to explore how others deal with unincorporated material or oversized specimens.

And so a group of us from Manchester visited the botany team at the herbarium at World Museum Liverpool.

We have been working on our spirit specimens in Manchester recently so were very interested in Liverpool’s spirit store and new jars.

We have been working on our spirit specimens in Manchester recently so were very interested in Liverpool’s spirit store and new jars.

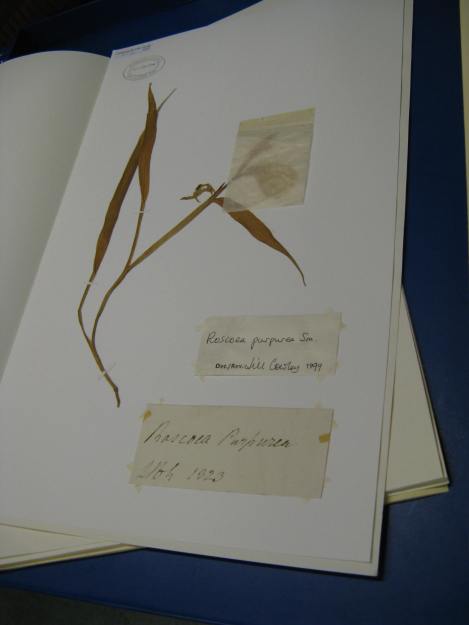

Liverpool Herbarium is incredibly rich in historical specimens. This is one collected by William Roscoe, a successful Liverpool lawyer and politician whose interests included history, poetry, botany, languages and art. He was the founder of the Liverpool Botanic Garden.

This specimen is of a plant named after Roscoe: Roscoea purpurea. Grown in the Liverpool Botanic Gardens, this specimen was taken in 1823 and is in the ginger family. It is native to the Himalayas.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester.

Historic Manchester (2)

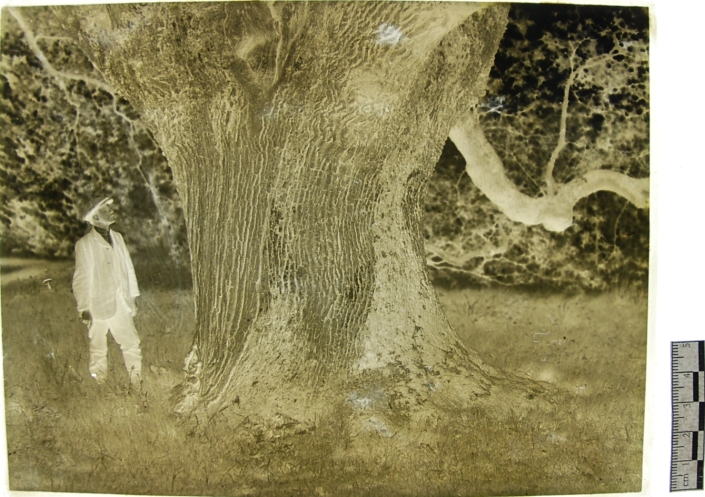

This is Abraham Flatters and his image is on a lantern slide which was used in a magic lantern as an early form of image projection. Abraham Flatters was an expert at making these and he went into business with Charles Garnett to form the successful company Flatters and Garnett.

They supplied both lantern slides and microscope slides on many aspects of Natural History to universities. Those which were bought by the science departments of the University of Manchester (then Owens College) are now in the Manchester Museum collections. We also have many of these very nice display boxes which demonstrate showing various features of british trees.

There is a very good history of this Manchester firm produced by the Museum of Science and Industry which can be read here. If you’re interested in the history of Manchester then there are more activities taking place in the city for the Manchester Histories Festival which comes to a close this weekend. Don’t miss the big Celebration Day at the Town Hall where we will be giving a selection of museum objects some time in the spotlight.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester and tagged Flatters and Garnett, lantern slides, microscope slides.

Corridors and herbarium sheets

Here are a couple shots behind the scenes today. Above, a pile of herbarium sheets to be filed away. These ones are Rubus specimens (brambles or blackberries) – there are hundreds of species around the world.

This is the East Corridor. The herbarium sheets are stored in the green boxes (they had to be green, for botany) and are sorted into geographical areas. This section of the corridor holds European specimens. The bench along the centre should be empty, for working space, but we had to empty out three large store rooms when dry rot was found in the floorboards, so our benches are currently storage areas. Not for too much longer, I hope.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester and tagged Herbarium, Leo Grindon, Manchester Museum, specimens.

Snowdrops: pearls of the opening year

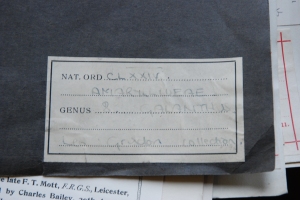

Putting away some specimens in the herbarium last week I noticed a folder labelled Nat. Ord. CLXXIV Amaryllaceae GENUS 8. Galanthus.

Snowdrops!

Unfortunately pressed flowers rarely keep their natural colours, and snowdrops are no exception – even though their petals are white. The flowers turn brown and the leaves darken too.

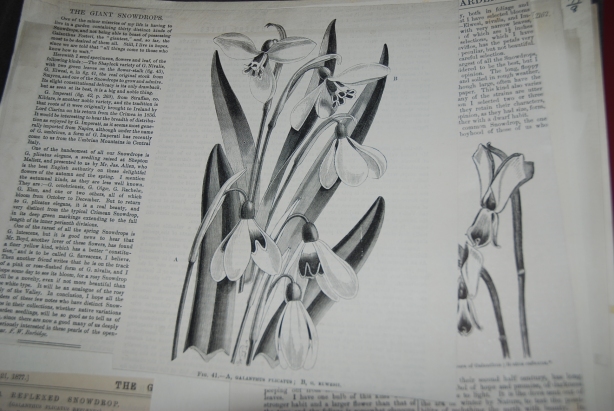

Our cultivated collection also includes illustrations. Below is a colour illustraion of ‘Eight kinds of Snowdrops’ from The Garden, dated 23 January 1885:

A short article in The Garden (no date, probably around 1886) by F. W. Burbidge begins, ‘THE GIANT SNOWDROPS. One of the minor miseries of my life is having to live in a garden containing thirty distinct kinds of Snowdrops, and not being able to boast of possessing Galanthus fosteri, the “giantest”, and so far, the most to be desired of them all. Still, I live in hopes, since we are told that, “all things come to those who know how to wait”.’

Burbidge goes on to describe the species and varieties of snowdrop giants in his garden. He concludes, ‘I hope all the readers of these notes who have distinct Snowdrops in their collections … will be so good as to tell us of them, since there are now a good many of us deeply and seriously interested in these pearls of the opening year’.

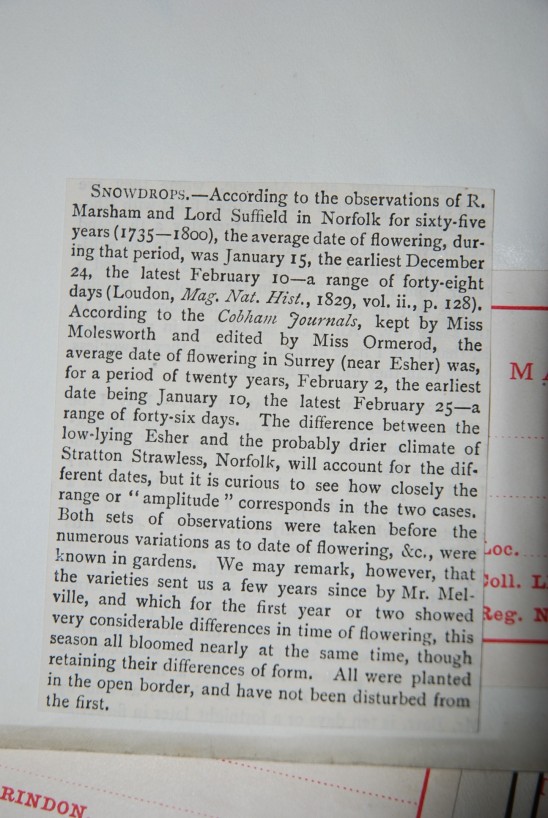

Another delightful little piece about the average flowering dates of snowdrops (probably dated around 1880 to 1890):

This entry was posted in Botanists, Herbarium History and tagged botany, burbidge, cultivated, galanthus, giant, grindon, Herbarium, illustration, Manchester Museum, pressed, snowdrop, The University of Manchester, Victorian.

Little creepers in the mud

Difficulties arise in identifying groups of plants for various reasons: some groups are just too large! There are a lot of umbellifers (the parsley family), not very similar to each other but it is hard to remember them all. Other groups consist of many closely related, and very similar, species whose identification requires very close examination (for example, the Lady’s Mantles (Alchemilla), or the Eyebrights (Euphrasia)). Others groups are difficult for other reasons and many may justifiably throw their hands in the air, or at least shrug their shoulders! Consider small creeping plants with smooth eaves in opposite pairs that grow in damp or watery areas, especially in mud, many of which root along their stems.* These are too inconspicuous for many to bother with, but come from a wide range of unrelated families. Not only do these look superficially similar, but some vary quite considerably accordingly to where they grow – they are `polymorphic’ – varying with the depth and speed of flow of the water and the substrate (mud, sand or rocks) and often looking very different in different environments. Worse than this, some rarely flower, so that no flowers or fruits are available and we have only stems and leaves for identification purposes.

So why bother with such difficult and inconspicuous groups? Well, that is what botanists do! And, as usual, the more closely we look, the more interest there is, and from such observations occasionally great discoveries are made. So with one such sample (above), gathered from a burn in Olav’s Wood in Orkney, I visited the University of Manchester Herbarium – a magnificent and historical collection, with approximately one million specimens many dating back to the mid 19th century. This is valuable not only as all good herbaria are – an important resource for plant sciences – but also because many of the specimens are from sites in the UK (and elsewhere) now lost, and moreover ancient specimens open up the possibility that we can examine how plants may have changed, even over 100-150 years. The difficulties of identification are shown in the herbarium specimens. Some of the Water starworts (Callitriche) have three labels attached over the decades with different names (partly because species boundaries have become clearer) and few have any flowers or fruit. Stace [New Flora of the British Isles, Clive Stace. C.U.P. 19191] says of the Water starworts “leaf-shape is notoriously variable and misleading” and “difficult to identify certainly without a strong lens or microscope”. I’ll only be satisfied if I can get my specimens to flower and fruit, but don’t wait around!

David Rydeheard

* Amongst such plants are the Blinks (Montia), Water starworts (Callitriche), Waterworts (Elatine), Bog stitchwort (Stellaria uliginosa), Water purslane (Lythrum portula), Pigmyweeds (aquatic Crassula species), New Zealand Willowherb (Epilobium brunnescens) and Bog pimpernel (Anagallis tenella). A useful article on these plants can be found in the BSBI (Botanical Society of the British Isles) News No. 106, September 2007: Maddening Mimics: a belated reply.

This entry was posted in Botanists, Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists.

Petty spurge: cancer treatment?

BBC news: garden weed could treat skin cancer.

Top image: Euphorbia peplus, petty spurge. A pressed plant specimen from the herbarium at the Manchester Museum. Collected by F C King in 1883 from waste land near Ribchester, Lancashire. Charles Bailey, a Manchester cotton merchant, then aqcuired it from King (donation? Exchange? Or purchase? – we don’t know) and left it and 330,000 others to the museum on his death in 1925.

Bottom image: illustration of Euphorbia peplus (common name: petty spurge) from the Manchester Museum’s cultivated collection. This and hundreds of other illustrations, plant cuttings and newspaper clippings were donated to the museum by Leo Grindon’s wife after he died, in 1911.

This entry was posted in Botanists, Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, News.