Claude Monet’s Haystacks

by holditnow

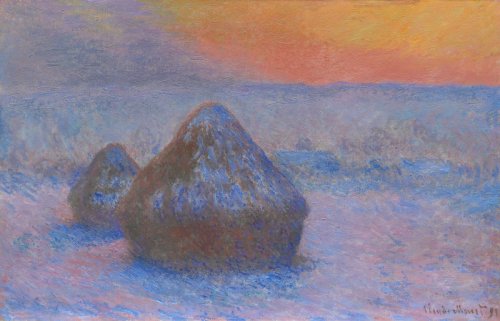

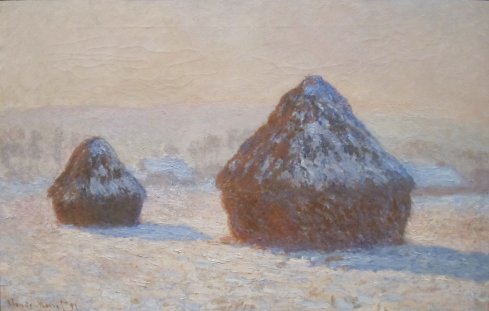

Between 1890 and 1891 Claude Monet (the father of Impressionism) painted roughly 30 paintings of Haystacks. They were the first of many series he would devote his life to. Not as beloved as his Waterlilies or showy as his Cathedral of Roen, the Haystacks signify a sea change in his approach to painting. The subject matter took a backseat to concept and technique. This was not lost on the critics of the day who immediately picked up on what Monet was pursuing. Monet wasn’t trying to capture the everyday banality of the rural French countryside, but rather the fleeting effects of light and time. This was and still is a radical idea.

Not everyone was as impressed with the idea as the critics: namely some of the farmers whose fields art history was being rewritten in. They would intentionally tear the stacks down to keep Monet out of their backyards. Luckily, enough of them didn’t care or in the case of the winter scenes were paid to leave them up. See, snow isn’t that great for your hay but Monet wanted to capture the effects. A few francs later and we now have some of the most dramatically orchestrated winter images in the history of painting.

In 1891 when they were originally exhibited, it was the first time an artist had shown a suite of paintings of the same subject matter that were intended to be shown together as a group. The subject was the same but the effects were diverse and varied. Colour was set free. Monet found the violet in the shadows created by the yellow sun, and notoriously swore off black stating ‘there was no black in nature’. Black eventually found it’s way back in, but near the end of the 19th century Monet wouldn’t even put it in his paint box when he left the studio to go capture the day’s light.

And capture the day’s light he did. Over the years my feelings towards the Haystacks have grown considerably. What I at first mistakenly perceived as too simplistic drawing, I now admire for their abstract qualities. In this day and age the Impressionists have been so universally accepted that it is easy to forget just how innovative, groundbreaking and polarizing they truly were and Monet’s Haystacks were on the forefront of that wave.

[…] via Claude Monet’s Haystacks — holditnow […]