Abstract

The problem with relative neglect of mycology in science is currently leading to insufficient knowledge in order to support the needs for fungal expertise in areas of forensic investigation: determining the minimum interval since death, locating clandestine burial sites such as mass graves, connecting victim and suspect, establishing locations, helping determine cause of death or discovering whether a body was moved. There are number of forensically related disciplines of science which combined together with the knowledge of mycology can be beneficial for the contemporary criminal justice system. This essay is focused on four, forensically important, domains of science: pedology, palynology, taphonomy and toxicology. Beginning with the examination of mycology in the realms of taphonomy, this study moves on to analyse mycology in combination with pedology and palynology. In the later part of this work the use of mycology in relation to toxicology is discussed, especially how indoor air quality and sick-building syndrome can play a significant role in forensic investigation if developed further. This study is concluded with the identification of current research and development opportunities in forensic mycology, problems related with funding, formalising forensic mycology as recognised discipline of science and scientific quality of existing research.

Introduction

“To be conscious that you are ignorant of the facts is a great step to knowledge.”

– Benjamin Disraeli, 1804-1881

This research will discuss the potential role of mycology with respect to forensic investigation; the discipline of science that was ignored or rather overlooked for a long period of time, before its appliance to forensic work was finally recognised.

As Richard Jantz (in Page, 2011, page 1), the director of so called ‘Body Farm’ at the University of Tennessee’s famed Forensic Anthropology Centre said, “No one here is doing anything (with forensic mycology) and we do not know anyone who is (…)” Although Jantz does not reject the forensic potential of mycology; “We would welcome the research,” he said (in Page, 2011, page 1).

This work is focused on four, forensically important, domains of science, pedology, palynology, taphonomy and toxicology which combined with knowledge annexed from mycology can prove to be of forensic value. This study will attempt to establish the connection between mycology and forensic science based on interactions among these two disciplines, with the use of vast literature review, followed by a critique analysis of gathered sources which are supported by a number of mycology-related forensic cases.

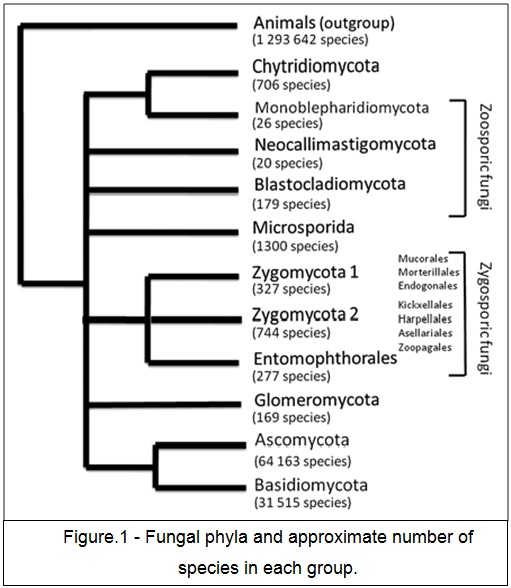

Mycology is the area of science involved in the study of fungi, which encompasses mushrooms, moulds, blights, plant and human pathogens, mildews, yeast, lichens and rusts. The application of mycology studies in order to produce evidence in terms of criminal investigation and their further evaluation in the court of law was in recent times only limited to cases of poisoning (Hawksworth and Wiltshire, 2011). However in the past few years following the development of research strategies in forensic mycology new applications were discovered and documented. Similarly to animals, fungi are unable to produce their own nutrients; therefore they have to obtain them, from living or dead organisms, or other organic materials. The UK Fungal Records Database holds approximately 14000 records of fungal species, where each year around 40 to 50 new species are discovered (British Mycological Society, 2009). There are roughly 10 times more fungi species in the UK than plants (approx. 1200 species according to British Plant Gall Society Checklist in British National History Museum) which might prove to be of a high forensic value considering how extensive the fungi family is in contrast to other British flora(Fitter and Peat, 1994). Over 700000 species of fungi are known world-wide (Schmit and Mueller, 2007). According to Hawksworth and Wiltshire (2011) around 800 new species of fungi are being discovered and classified every year, world-wide. Using these numbers, it can be estimated that approximately 1.5 million species of fungi can exist world-wide (see Fig.1, Kirk et al., 2008). Differences in fungi species estimation, over the period of 4 years, based on calculations provided by the teams of researchers; Schmit, Mueller and Hawksworth, Wiltshire vary over 47%. That can either indicate the inaccuracy in data gathering or rather the unpredictability in fungi expansion and multiplication of species. Blackwell (2011) indicates that the large increase in species numbers in recent years may be inflated because asexual and sexual forms of fungi were counted separately and molecular techniques that distinguish close taxa (unit in the biological system of classification of organisms) have been used.

Page (2011) concludes that forensic mycology, although a still scarcely developed discipline can be of great value to forensic science. In addition to its importance in cases of poisonings, other examples of use include: determining the minimum interval since death, locating clandestine burial sites such as mass graves, connecting victim and suspect, establishing locations, helping determine cause of death or discovering whether a body was moved.

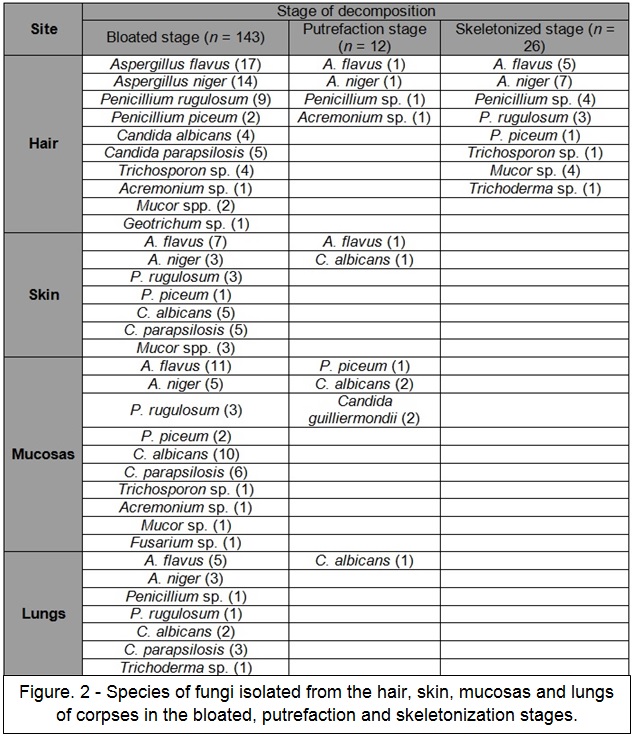

Alongside the research in forensic entomology (discipline based on the research of flies and other insects that colonize on the dead organic matter) a number of fungi species have also been discovered. Fungi have already been detected on a mummified remains and skeletal debris, but unlike a skeleton or fossil, a mummy retains some of the body’s soft tissue (skin, organs and muscles) it possessed when still alive (see Fig.2, Sidrim et al., 2009). Despite these discoveries more forensic cases and research is required to establish fungi as a useful forensic tool (Masahito et al., 2006). Forensic pathologists have found fungi mostly on decomposing human matter, therefore it is believed that discovered fungi could be developed into an effective forensic tool for establishing the post-mortem interval in cadavers that have decomposed over a long period of time, although in some cases fungi were reported to be found even 10 days after death (Page, 2011).

A burial environment is a complex and dynamic system that involves collaboration between chemical, physical, and biological changes (Sidrim et al., 2009). The fruiting structures (aka. sporocarps; multicellular structure on which spore structures are grown) of some fungi, the ammonia and the post putrefaction fungi, have been discovered on a number of occasions in connection with decomposed mammalian cadavers in disparate regions of the world (Carter and Tibbett, 2003). Studying the ecology and physiology of these fungi has potential as a forensic tool.

In the last 50 years, fungi have become important pathogens. Before the mid-60’s, reports of fungal infections were narrowed down to occasional autopsy series or brief notations in academic research, while currently the number of fungal species reported as being opportunistic agents of human disease is increasing by about 10 to 15 per year (Cimerman et al., 1999). Fungal infections on living and dead tissue can possibly give away much more useful information for forensic investigators when combined with medical records of victims or suspects. Symptoms of toxic mould exposure or mycotoxicosis are multiple and can be life threatening. Mould toxicity is not easily detected although when found, it can lead to identifying the primary place of intoxication and detect movement of the body (from/to an inside/outside of premises) after death.

In order to obtain fungal species while conducting outdoor searches, mycologists depend on their optic vision, magnifying glass, and primarily on their knowledge of which habitats might prove fruitful. There are certain situations where investigating officers can utilize mycology in order to gather evidence. For example, to create the palynological profile of a crime scene, especially in an outdoor environment, when PMI (post mortem interval) or body deposition is uncertain, and fungal colonies are evident on human remains, clothing, or associated items (indoors or outdoors) (Page, 2011). Mycology can be a significant aid when the use of entomology is not applicable. Despite the presence of entomological evidence, utilization of knowledge about fungi can be used to establish a separate line of inquiry. Mycology can also be used in situations when a seizure of trace evidence produced data of fungal spores or when suspects are found to be in possession of mushrooms associated with neurotropic (affecting nerve cells) behaviour or when fungi have been detected in gut contents, food or drink.

The ‘orphan’ nature of mycology can be problematic as fungi lack close relatives, they are misunderstood and often excluded from ‘family events’, many are unnamed, furthermore they are often simply overlooked or ignored (Hawksworth, 1997). The neglect is so grave that mycology does not even feature as a separate subject in the categories of science recognized by UNESCO; these only mention fungi as mushrooms under ‘botany’ and as yeast under ‘microbiology’ (Rai and Bridge, 2009). According to Hawksworth (1997) the most important consequence of relative neglect of mycology in science, is that there is insufficient expertise to support the needs for fungal research in areas of direct human concern: human health, food security, food safety, plant diseases, forensics, bioterrorism and biodeterioration. Rai and Bridge (2009) summarise it simply, by saying that the quality of investigations in pure and applied sciences that depend on aspects of mycology is suboptimal. The ‘orphan’ nature of mycology has been presented previously (Hawksworth,1997). Fungi lack close relatives, they are misunderstood and often excluded from ‘family’ events, many are unnamed, they are often overlooked orignored, have few carers and are inadequately provided for. The neglect is sograve that mycology does not even feature as a separate subject in thecategories of science recognized by UNESCO; these only mention fungi asmushrooms under ‘botany’ and as yeasts under ‘microbiology’. In order to establish mycology as a widely accepted forensic tool, systematic experimental testing of specific fungi under specific conditions has to be conducted to achieve predictable outcomes (Page, 2011). However it seems to appear that no one is conducting enough relevant research, so far. “The principal reason for the absence of mycological protocols is a lack of awareness amongst crime scene investigators that fungi have the potential to make significant investigative contributions,” said David Hawksworth (in Page, 2011, page 2), of the Department of Biology at the Natural History Museum, London. One of the few scientific institutions that carries out research, relevant to forensic mycology is the Department of Biological Science of Birkbeck College, University of London (Research and Development in Forensic Science: a Review, 2011). Efforts are focused on analysis of fungal species diversity and succession in the estimation of PMI using animal analogues (pig), using material associated with murder victims (blood spatter, food, etc.) and deposition times of fungal spores (which may relate to post mortem interval) through direct field observation both indoor and outdoor. Taphonomic factors affecting fungal spores in palynological profiles are also taken under consideration as well as use of mycotoxins in forensic toxicology. In order to obtain as much important forensic data as possible through the use of mycology, it is important to combine that particular field of science with other already well established ‘cousins’ of forensic science; pedology palynology, taphonomy and toxicology.

Mycology and taphonomy

Taphonomy is the study of the processes that affect the decomposition, dispersal, erosion, burial, and re-exposure of organisms after, at, and even before death (Nawrocki, 2006).

The use of mycology by forensic investigators can reveal a lot of useful information, if fungi could be proven to grow predictably in a given environment as insects are. Mycology could also be used to determine the post-mortem interval (Page, 2011).

According to Janaway (1996) fungi which are commonly discovered colonising dead organic matter, are the species unable to grow on a living tissue. Notably, there is insufficient data on the particular role these fungal species play in the decomposition of cadavers (Carter et al.,2007).

Remains buried underneath the soil have been repeatedly declared as displaying symptoms of decomposition related to moist environment, accompanied by skin slippage and the steady sprouting of fungus (Galloway, 1997). Janaway et al. (2008, page 314) concluded that fungi growing in soil can be colonizing the surface of the body “after the major phase of decomposition”, and observed that “moulds begin to appear on the surface of the body” as soon as a week after the death occurred. Decomposition of the body with fungal and mould infestation can be explained. The outer surface of the living tissue is composed of dead debris. This dead outer layer is essential in ascertaining the correct functioning of the human body. When as a result of regular process, new tissues are formed underneath, the outer stratum corneum (the outermost layer of the epidermis, consisting of dead cells [corneocytes] that lack nuclei and organelles) is shed as dander (material shed from the body of various animals, similar to dandruff) (Pinheiro, 2006). Therefore when the outer layer of the skin is shed, small spores of moulds and fungi that have been colonising that surface are also disposed of. After the dead surface of the skin does not produce any new tissue, moulds and fungi start to develop on the outer regions of the cadavers, frequently developing evident ‘coating’ of fungi on the dead corpse (Amendt et al., 2010).

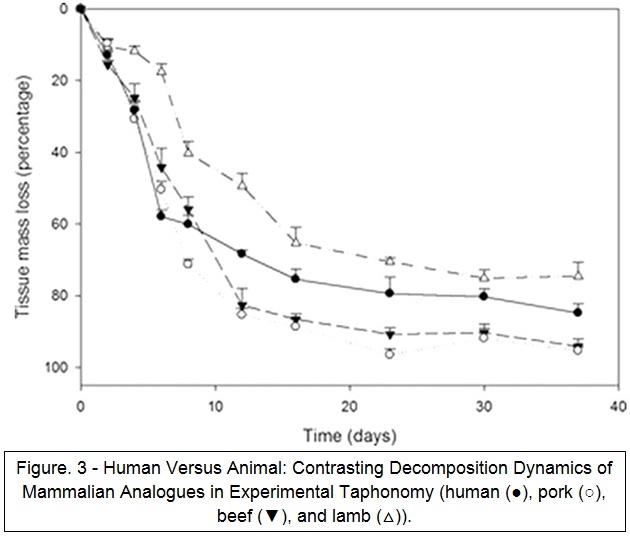

Fungal growth is often observed during decomposition (Sagara et al., 2008). In relevant research, fungal growth has been observed and identified to varying taxonomic levels (Stokes et al., 2013). For porcine tissues, ascomycetes and zygomycetes have been reported (Forbes et al., 2005). In human cadavers, some research has observed fungi (Cabirol et al., 1998) with growth of Eurotium repens, E. rubrum, E. chevalieri, and Gliocladium discovered in one case (Ishii et al., 2006). In this study by Stokes et al. (2013) microcosms containing human SMT (skeletal muscle tissues) showed abundant fungal growth within 3 days of inhumation (see Fig.3). It was not established if that was a result of peri- (at or near the time of death) or antemortem (preceding death) infection in the human subject or a real difference in effect on the soil microbial ecology.

In one of the cases for Hertfordshire Constabulary small colonies of non-sporing Mucor hiemalis were used to roughly establish PMI. The size of the colony and the early stage of fungi growth suggested 1 to 2 days, and the intact state of the mycelium (pl. mycelia) (the vegetative part of a fungi, including a mass of branches) demonstrated that it had sprouted in situ after the cadaver was dragged across the creek (Wiltshire, 2008). A report from the case in Hertfordshire discussed certain species of fungi, such as Mucor, being unable to grow on recently dead matter as on average that takes place at least one week after death. Hawksworth (2008) suggests that this reinforces the theory as to the victim being murdered and kept in another remote location, while being dumped on the deposition site only for a brief period of time.

Fungi are heterotrophic (they are unable to produce their own) for carbon compounds and number of specific nutrients (Carter and Tibbett, 2003), which means they must acquire them as a consequence of saprophytic and parasitic bonds with their hosts which link them to numerous decomposition mechanisms. Cadaver decomposition can be directly connected with two main groups of fungi: ammonia fungi and post-putrefactive fungi. Ammonia fungi can be identified as two separate categories; early and late stage fungi. Division into two groups is based on previous examination of fungi successions during decomposition of dead organic matter, which is accompanied by realising of nitrogenous compounds by cadavers. Early stage fungi are represented by: ascomycetes (aka. cup fungi, an edible group of fungi), deuteromycetes (fungi that reproduce only by an asexual process) and saprophytic (that grows on dead or decaying organic matter) basidiomycetes (fungi that reproduce sexually via the formation of specialized club-shaped ends), whereas late stage fungi group consist of ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes (Carter and Tibbett, 2003). When looking at current forensic investigations, noticeable amounts of mycelia are detected, therefore further examination of human corpses in relation to produced fungi can become forensically significant if the connection between them and dead matter can be found predictable and reproducible (Vass, 2002).

One of the first teams of researchers acknowledging the possible importance of fungal development of human cadavers in correlation with estimating PMI were van de Voorde and van Dijck (1982). The duo managed to isolate fungal sprouts from an eyelid and lower lateral region of the abdomen of a female murder victim in Belgium. In their work Hawksworth and Wiltshire (2010) further explained how fungal isolates were incubated at the temperature corresponding to the one in which the body was discovered (12°C constant regulated using a thermostat) and measurements of the fungal spores were taken each day. The rough assessment of the time of death, based on taken measurements, was believed to be 18 days prior the discovering of the corpse, which was later confirmed by the suspect. That gave the idea for further research on fungi being useful in estimating PMI, based on temperature readings and state of development of fungal colony.

In another interesting example, the corpse of a male was discovered near the underground line in Ruislip, North West London. Primary examination concluded life ended no more than 48 hours prior to discovery. No entomological or animal activity was noticed. However, investigators discovered substantial fungal mats underneath the victim’s jaw, indicating that the corpse was lying in situ for between 3 to 5 weeks, (Hawksworth and Wiltshire, 2010) which was extremely accurate considering the actual period of time established later in the investigation was 4 weeks. Factors that contributed to such inaccurate estimation at the beginning of examinations were; extremely cold weather (which excluded entomological growth) and secluded, confined, area preventing animal activity.

In 2006 another attempt to use fungi as a marker for PMI in a criminal case was undertaken. The research was concentrated on the two types of fungi (Penicillium and Aspergillus) discovered on corpse (believed to be of 71-year-old man) lying in a well in Japan approximately 6m under the ground level of his garden. Species of previously mentioned fungi have ability to colonize matter after 3 to 7 days from landing on the surface of the object. The condition of the outer surface of the cadaver and developed stage of decomposition of internal organs gave Japanese police intelligence that allowed estimating PMI around 12 days prior the body was found. Although the fungal evidence indicated that the man had been dead for about 10 days, using the known growth cycles of the fungi that were detected on the carcass (Masahito et al., 2006).

Apart from being helpful in estimating the post-mortem interval, fungi can be also used to determine the cause of death. Fungi are not usually used as murder weapon. Generally they are only encountered when people consume them by mistake. There are two main groups of poison mushrooms, amanita and ergot groups. Symptoms of the most fungus poisons from amanita group include sudden onset of nausea and vomiting, colicky abdominal pain and profuse watery diarrhoea (Harmful substances, 2011). There is a reprieve false recovery when these symptoms resolve, only to be followed a day or two later by signs of fulminant liver failure (jaundice which is a yellowish pigmentation of the skin, leading to delirium, seizures and coma). Renal failure and coagulopathy (a condition in which the blood’s ability to clot is impaired) are complicating factors leading to death after 6 or more days. Important for pathology are biomarkers of hepatocellular necrosis (types: AST/ALT, ALP, and LDH) which rise rapidly from about 36 hours after ingestion. These liver function tests serve as clinical biochemistry laboratory blood assays, constructed in order to provide data about the condition of a patient’s liver. The liver typically shows fatty degeneration with central zone necrosis and centrilobular (pertaining to the central portion of small division of the liver) haemorrhage (Harmful substances, 2011).The ergot group poisons are best represented by hallucinogenic alkaloids, such as psilocybin, where overdose can lead to death.

A new private initiative combining science with socio-art came to life in 2011. The Infinity Mushroom project aims to cultivate specific strains of fungi in order to ‘train’ them to decompose human cadavers and, in addition, eliminate industrial toxins in bodies. The idea for cultivation of the Infinity Mushrooms derived from entomologist Timothy Myles (2003) who was first to use the term decompiculture (growing or culturing of decomposer organisms by humans). Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) and oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), mycological tissue cultures, were used in order to further develop that technique. These fungi are known to grow and develop on decaying wood and related forest material, furthermore they can be targeted to sprout on any organic material and decompose it. Jae Rhim Lee (2011), who graduated from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is currently trying to develop fungi that would be able to decompose specific body tissues and body excretions, such as skin, hair, blood, fat, tears, urine, faeces, etc. In order to do that selected fungi have to be able to absorb nutrients from human organs and tissues. The Infinity Mushroom project consists not only of specially cultivated fungi but also of an organic cotton suit with crocheted netting on top, in a pattern resembling the growth of mushroom mycelium, and the netting covered in gelatine on which the ‘Infinity Mushroom’ spores will initially grow (Lee, 2011).

Mycology, pedology and palynology

Pedology is a category of soil science concentrated on the formation, morphology, and classification of soils as bodies within the natural landscape (Jackson, 1997).

Palynology can be described as a study of dust particles. The circumstances and recognition of those particles, organic and inorganic, can provide a palynologist with a better understanding to the environment, and energetic settings that created them (Sarjeant, 2002).

Since distinctive numbers of diverse fungi can be obtained from each single soil sample it allows mycology to be used in order to establish the location of the burial site based on characteristics of soil samples.

Similar to techniques used in forensic entomology, mycological evidence can be exploited to estimate how long a body has been in a specific outdoor location long after decomposition has set in. If a body is dumped on top of living fungi, the loss of light and pressure of the body will cause the covered fungi to change their colour, therefore estimates of when a body was disposed of is sometimes possible, based on the stage of development of the fungi and the degree of its discolouration (Bell, 2009). Similar behaviour can be noticed when fungi colonize skeletal remains. Expertise on fungi succession can also be used in order to determine clandestine burial locations. During the ground disruption caused by grave digging and soil shuffle, existing fungi can be damaged or moved. These disrupted fungi will be scattered around the fresh grave, forming a pattern that will be distinct from other surrounding fungi. The disrupted fungi pattern can be preserved in the same form for years which makes it easy to spot the grave to the trained eye.

The use of mycology by forensic investigators can reveal a lot of useful information about movement of the body after or before death. Specific species of fungi are particular of disturbed soil and will not grow sporophores (an organ in fungi that produces or carries spores) till 1 to 2 years after the ground has been disturbed (Hawksworth and Wiltshire, 2011). Certain fungi species possessing this characteristics makes them simple to identify, especially Shaggy ink cap (Coprinus comatus) fungi and certain species of Morels (primarily Morchella species). Broken or dislocated logs and branches can help in discovery of dead bodies due to the fungal indications caused by some sort of impact on their surface. Mushrooms are generally geotropic (growing downwards), including vertical stalks (stipes) and horizontal caps (pilei). When their structure is disturbed, stalks of fungi tend to curve while growing back, trying to recover their previous vertical position or in some examples their caps bend horizontally (Moore et al., 1996).

A case reported by the South Wales Police, presented how these unique characteristics of fungi can be used to negate the allegations of the witness, who discovered a body deposition site, where he stated he had not touched the cadaver nor moved any objects, while at the scene. Wooden logs put on top of the grave’s soil by the perpetrators became the foundation to many sporophores (a spore-bearing structure) of a Marasmius (small, brown mushrooms) species. The positioning of the stalks and caps revealed that a number of the wooden logs had been re-oriented before the witness report, therefore, based on these information his testimony was discredited (Wiltshire, 2004). Occasionally time is a critical factor in this kind of inquiries. Simple, quick and inexpensive experiments can be possible to perform in order to measure the length of time necessary for rebuilding destroyed structures of the fungus.Lichens in most cases colonise sides of branches that have a good source of sunlight, therefore if they are discovered underneath e.g. wooden log it is possible to draw a conclusion as for the branch to be disturbed. Furthermore, certain species of lichens change their colour before decomposition if they have been dislocated or covered from the source of sunlight. This characteristic behaviour can be observed in shrubby and foliose species containing β-orcinol depsidones (class of chemical compounds that are esters) like norstictic or salazinic acids (e.g. Parmelia and Usnea species) causing them to change their colour to pink or red if dislocated to dark or mist locations where they slowly wither (Lamb, 1964). CSI’s and other officers examining fungal material should be aware of these characteristics as they might have evidential value and be helpful in pinpointing disturbed twigs and other botanical material. Furthermore knowledge of the fungi behaviour can assist in analysing suspect’s approach paths at the crime scene, as well as aid in discovering burial sites.

Another case reported by Wiltshire (2009) illustrates a possibility of providing data, using mycological material, on the PMI of a body part (which was wrapped in plastic by the perpetrator) that had lain in situ. A colony of lichens of Xanthoria parietina was found underneath the wrapped body part and nearby disturbed twig. Xanthoria parietina is a species of lichen which under the exposure to sunlight can be of a yellow or orange colour. It can be identified by its characteristic orange sporophores. On the other hand when exposed to dark and wet conditions, the lichen assumes grey to green colourisation (Lindblom, 1997). Knowing the life cycle of the lichen and its characteristic behaviour, investigators were able to estimate the time when the body part was placed on the site.

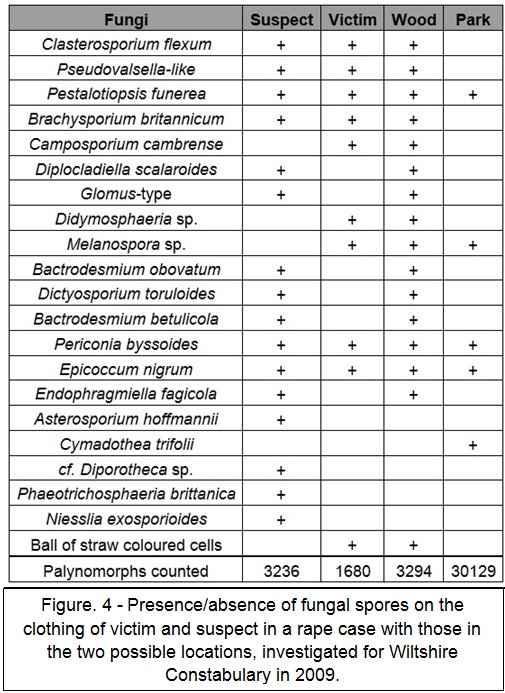

Under current research levels, with the help of data obtained from pollen material it can be noticed that fungal spores can improve level of match accuracy between evidence gathered from victims and suspects. Often rare fungi spores discovered in palynological evidence can augment the importance of mycological exhibits. Mycology as a factor enhancing deductive skills of investigators can be validated by a case of rape examined in 2009 by Wiltshire Constabulary. The female victim testified that she was sexually assaulted and then raped in the area next to the park trees, but the suspect denied allegations saying he had a consensual sex on the grass with the victim, approximately 200 m from a location described by the woman (Hawksworth, 2009). A fungi profile of the area was created (see Fig.4).

19 characteristics of dead leaves and twigs, descended from plants from the park, were discovered on the clothing and shoes of male suspect and female victim. Out of 19 characteristics, 16 of them, when compared to control samples, matched the area where the victim claimed to be raped.All palynological evidence were gathered, along with the fungal samples, to reveal that, despite a small distance and (at the first sight, similar) environment, the two disputed areas can be easily distinguished between each other. That lead to establishing that the female’s testimony was true. Unfortunately to call findings convincing in court a palynomorph count (pollen, plant and fungal spores) has to be significantly big (in this case over 38000) to be considered sufficient (Hawksworth, 2009). The outcome of the investigation was satisfactory as suspected rapist claimed guilty after he faced the palynological evidence.

Another factor that can aid in forensic investigation is the seasonal character of mushrooms. Some of them are restricted to certain time of the year and surrounding environment, e.g. Sarcoscypha species or Golden needle mushroom(Flammulina velutipes) (Roody, 2003). The first one appears in the early spring on fallen twigs while the second one sprouts after the first frosts of winter. That kind of mushrooms with characteristic spores can prove to produce evidence if damaged or moved by a suspect. Furthermore, Hawksworth and Wiltshire (in Page, 2011), discovered that sampling vegetation, soils, and microscopic exhibits of plant and animal origin can produce data on fungal species that are extremely rare. Once during a search, the team discovered characteristic spores of Caryospora callicarpa, even though for the last 150 years none of its specimen has been encountered in the UK. After consultation with Hawkworth’s, Wiltshire expressed opinion that a distinctive number of soils, other deposits, and vegetation can be characterised. “We’ve been able to match crime scenes to items retrieved from suspects, such that contact of the item with the place has been convincingly demonstrated many times,” Wiltshire said (in Page, 2011, page 3). Discovering a rare species of fungi at a crime scene can improve the quality of palynological data. Once gathered fungal data is combined together with pollen and plant material the evidence can become very conclusive. Due to fungi being species requiring specific habitual and nutritional conditions, collected fungi can signify particular environments. In case from 2008, Lincolnshire, a couple of animal rights demonstrators were held in custody based on intelligence stating that they might have been connected to an attempted break-in on the grounds belonging to the laboratory-farm which specialised in breeding rabbits for scientific purposes (Hawksworth, 2009).

Suspects’ footwear was seized in order to obtain a palynological data which would be later compared with control samples seized at the scene of the break-in. A number of exotic plant pollen and fungi were discovered. It was established that found material originated from imported food used to feed rabbits. Altogether samples from the footwear and control samples produced 21 fungal taxa, identifiable to genus and species (Wiltshire, 2009). 19 out of 21 fungal taxa could be directly connected to the arrested animal rights activists, furthermore 3 out of 19 fungal taxa could be matched to FRDBI (The Fungal Records Database of Britain and Ireland); which gave solid foundations to label them as rare. According to Wiltshire (2009) a mixed collection can provide a unique palynological profile that could show connection between the rabbit farm and activists, therefore being able to obtain so many specific markers, and regarding some fungal taxa being matched to FRDBI, the probability of the exact same collection appearing in any other local environment is highly unlikely.

Fungi found in soil are truly varied; 50 to 100 distinct species can be collected from a random sample of soil (Bills et al, 2004). Furthermore approximately 3 km of fungal hyphae (collective of vegetative parts of fungi) can be extracted from 1g of dry soil sample (Bardgett, 2005). Even if samples are collected from the same small area fungal profiles can vary greatly, as seen in research by Ascher et al. (2009) where samples from underneath the same species of trees growing no further than 20 m apart from each other turned out to produce hugely different taxa.

Another case reported by Hawksworth (2008) for Hertfordshire Constabulary, was a discovery of horribly disfigured body of a murder victim, positioned face down next to a narrow creek. There was no blood discovered at the scene indicating that the crime took place in another location. Visible colonies of Mucor hiemalis (a non-sporing fungi) were found on the ventral surface of the victim’s body and further analysis revealed that mud, in which the body was covered, must have originated from the creek which indicates that the victim was previously submerged in or carried through it (Hawksworth, 2008).

A different case described by Hawksworth (2008) was a drug-related shooting, where one of the suspects killed his associate. The gunman was suspected to have stood on the ground covered in leaf and twig material, while being hidden behind an oak tree, waiting to assassinate his partner. Suspects’ footwear was seized in order to obtain a palynological data which revealed oak trunk, cypress branches followed by leaf and twig material. A control sample collected at the scene and from the victim corresponded to a previously seized palynological profile. Discovered spores of Pestalotiopsis funerea (known as plant pathogen)and Endophragmiella (a pale orange fungi, found on rotten stems)species were part of that profile. The same spores were later collected from an inside of the vehicle which was used by both, suspect and his dead associate. Even though the palynological data provided damaging evidence itself, identification of specific species of fungi brought additional data for the court to deliberate on.

In the last case scenario, reported for Tayside Police in 2009 (Hawksworth, 2009), a victim of a brutal assault was stabbed numerous times and died as a cause of received injuries. A murder took place in a small flat which prevented entomological activity. Investigators discovered colonies of fungi growing on the flat’s furniture and sofa, the areas covered in blood. After removing the dead body humidity meters were set up on the crime scene. Data was recorded showing 30 to 34 per cent humidity. In this particular case, application of simple experimental methods can be noticed. Fungal colonies were measured in situ and later replicated in the lab. Control samples of furniture were taken and left to dry for further examination. No subsequent growth occurred within 5 days (Hawksworth, 2009). Observed aftermath in freeze of fungal growth was very conclusive as mould fungi sprout in conditions above 95% of humidity (Bonner and Fergus, 1960), therefore their growth at the crime scene depended on the moist from the blood deposition. Both samples from the crime scene and control samples of the fungal colonies indicated that the murder took place approximately 5 days before the cadaver was found, which was later confirmed to be true by the suspect.

Wiltshire (2009) noticed that in recent years more actions have been taken to prove forensic, and more importantly, scientific importance of palynology by developing test trials which included statistical techniques in combination with mathematical modelling. Other factors such as aerobiological (airborne biological materials) information and pollen calendars are not considered as valuable source of evidence in forensic context as they are not considered by court. As for today, in context of forensic science, it is highly unlikely to produce useful databases of the mycological characteristics of different environments; predictive models will always be crude and unlikely to be of practical value (Wiltshire, 2009). Conversely, the experienced ecologists/palynologists like Wiltshire and Hawksworth have been able to determine places, establish connections linking objects and places, roughly calculate time when a body was deposited, and discriminate between relevant and irrelevant locations. Despite current inability to produce indisputable mycological evidence in court, so far there has been no substitute for examination of mycological data in criminal investigation.

Further research of manmade decomposition fungi can prove fruitful and support forensic mycologists with additional data. Scientific bodies might consider collaboration (to ensure high scientific standards) with, for example, ‘The Infinity Mushroom’ project (mentioned previously). Such ‘art-science’ mixture, already attracted few people ready to donate their bodies in order to conduct more research (Lee, 2011), therefore opportunity to test PMI based on fungi using human cadavers rather than pigs (as in case of the Department of Biological Science of Birkbeck Collage, University of London), arise.

Mycology and toxicology

The main emphasis, in relation to toxicology combined with mycological evidence, is placed on mycoses (fungal infections) and mycotoxines. These fungal agents may be of high forensic value in terms of detecting environmental backgrounds of suspects/victims, matching between scenes/tools/objects as well as establishing contributory factors prior to death. Ramirez et al. (2012) indicates that some microbes can travel from the mucosal surface to diverse body tissues and fluids and, in theory, lead to microbiological degradation of drugs and poisons affecting their concentrations or metabolic profiles in the body.

According to Kwon-Chung and Bennett (1992) the fungi responsible for causing mycoses can be separated into two categories: primary pathogens and opportunistic pathogens. Opportunistic pathogens in contrary to primary pathogens, which under normal circumstances infect healthy humans with fully functioning immune system, affect people with compromised immune system. The process of pathogenesis of both primary and opportunistic fungi is complex, resulting in some diseases remaining centralised, while some evolve into systemic infection, e.g. numerous mycoses can enter the host body through the pulmonary tract, but also as a result of direct inoculation through the contact with a skin (Bennett and Klich, 2003). According to McNeil et al. (1996) one way, in which mycoses are frequently acquired, is direct inhalation of fungi/moulds spores from a surrounding environment or atypical expansion of a commensal species that usually colonise the surface of human skin or the gastrointestinal tract. People are at risk of fungal infections when taking broad spectrum antibiotics for a long period of time as the antibiotics kill not only harmful bacteria, but beneficial bacteria as well (McDonough, 2011). From a forensic point of view if traces of fungi colonising tissue of a cadaver are detected, they can provide background information about victim’s previous medical conditions depending on what body part is affected as well as supply intelligence as to the type of the environment where victim is found. In contrast to mycoses, mycotoxicoses are examples of “poisoning by natural means”, therefore are similar to the pathologies originated by contact with pesticides or heavy metal residues (Bennett and Klich, 2003, page 497). Bennett (1987) concludes that mycotoxins are products of natural origin that consist of small molecules. Mycotoxins are by-products of fungal metabolites and the same groups can prove to be toxic to plants, invertebrates and other microorganisms at the same time.

The word mycotoxin was used for the first time in 1962 after the sudden, substantial poultry death on the outskirts of London, where it was estimated 100000 turkey fowl died (Blout, 1961). After the turkey ‘X’ endemic was finally connected with contaminated groundnut turkey food which contained Aspergillus flavus aflatoxins, researchers and scientists world-wide realised the possible deadlines of mould metabolites.

Forgacs and Carll (1962) extended the mycotoxin ‘family’ by including earlier known fungal toxins, such as: ergot alkaloids, compounds originally described as antibiotics, with newly discovered secondary metabolites, like ochratoxin A (e.g. patulin).

The period between the beginning of 60’s and the middle of 70’s has been described as the ‘gold rush’ for mycotoxins, purely due to the fact that numerous scientists aligned with generously financed research in order to discover new toxigenic agents (Maggon et al., 1977). As a result, around 300 up to 400 different compounds were classified as mycotoxins (Cole and Cox, 1981).

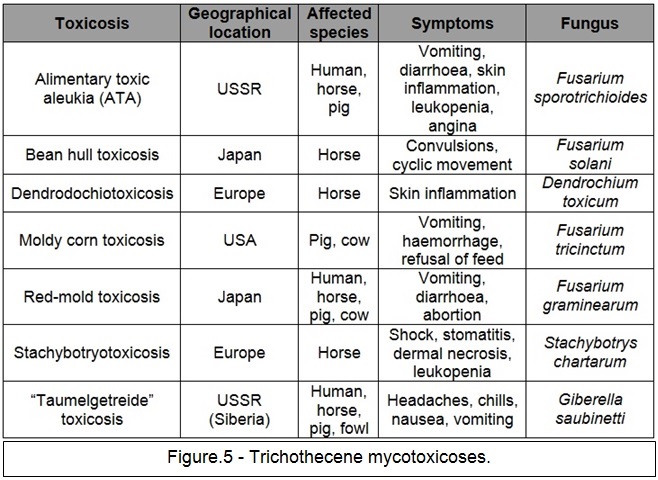

Despite the fact that toxins produced by fungi, as their metabolites, can account for possible terminal conditions in humans, they are not always categorized as mycotoxins; moulds are what constitute mycotoxins. Mushrooms and macroscopic fungi are discussed in terms of mushroom poisoning. Bennett and Klich (2003) emphasise that the difference between a mycotoxin and a mushroom poison is not solely based on how big the fungus that generates the poison is, but also on people’s intent. Moss (1996) points out, that only a small number of murders are committed using mycological toxins, with the exception of biological warfare, where mycotoxins like T-2 are currently in use (Wannemacher and Wiener, 1997). Poisons derived from mushrooms are commonly ingested by inexperienced mushroom pickers who have eaten what was wrongly assumed to be a delectable species. T-2 mycotoxin has been classified as produced by trichothecene (see Fig.5) which is a natural mould occurring as a by-product of Fusarium spp fungus. T-2 is considered to be highly toxic to humans as well as animals. The medical complications caused by T-2 are; alimentary toxic aleukia (an absence or extreme reduction in the number of white blood cells) and numerous other symptoms connected to organs, skin, airways and gastrointestinal track (Boonen, 2012).

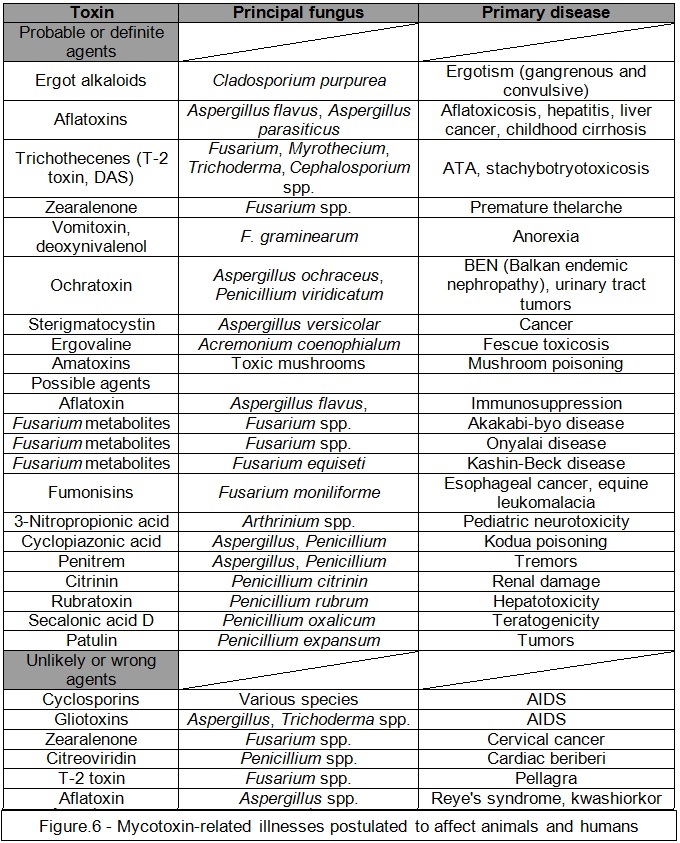

Currently recognition of an impact that mycotoxins have not only on animal but also on human health is highly admitted (see Fig.6, Kuhn and Ghannoum, 2003). Mycotoxins exhibit a wide array of biological effects and individual mycotoxins can be mutagenic, carcinogenic, embryotoxic, teratogenic (causing deformation of an embryo or fetus) or oestrogenic (Smith et al., 1995).

Bennett and Klich (2003) points out that the potential of fungi growth at the same temperature as of human body (37°C) is an essential factor for mycotic infection, although preferred temperature for majority of mycotoxins vary between 20 to 30°C, therefore a post-mortem infection can be excluded.

There is limited information about the effects that mycotoxin intake have on human subjects. Being able to establish a connection between mycotoxin exposure and human disease is further complicated by doubts linked to human epidemiological studies (Smith et al., 1995). There are different symptoms of the exposure to mycotoxins; depending on what kind of mycotoxin is discussed. Key factors establishing what kind of mycotoxin is dealt with are: concentration and duration of exposure, basic factors like gender and the age of infected person. There are also secondary factors such as diet, previous medical history and genetics. Bennett and Klich (2003) argue that, on contrary, mycotoxicoses can increase the likeness of microbial infections and interact synergistically with other toxins. According to Smith (1995) the total amount of consumed mycotoxins in most EEC (European Economic Community) countries is believed to be relatively small, although exact numbers of individuals affected by mycoses and mycotoxins is currently unavailable. In developed countries, mycotoxins are generally found in humans whose immune systems have been weakened by extensive medical treatment in the past (Bennett and Klich, 2003). A common characteristic possessed by both, mycoses and mycotoxicoses is that they cannot be transferred from one individual to another. This can be used in forensic investigation in order to establish from what part of the world a certain person came from. According to Barrett (2000), mycotoxin infection is possible to appear in parts of the world where poor methods of food handling and storage are common, where malnutrition is a problem, and where few regulations exist to protect infected individuals. Nevertheless, even in developed parts of the world, certain subgroups can be exposed to mycotoxin infection. Surai et al. (2010) points out that in the USA, Hispanic minority is considered to consume higher amounts of corn-related products, which are prone to mycotoxins infections, in contrast to the whole USA population. Also it has been discovered that people living in cities are more prone to occupy a household with high levels of fungi and moulds (Barrett, 2000).

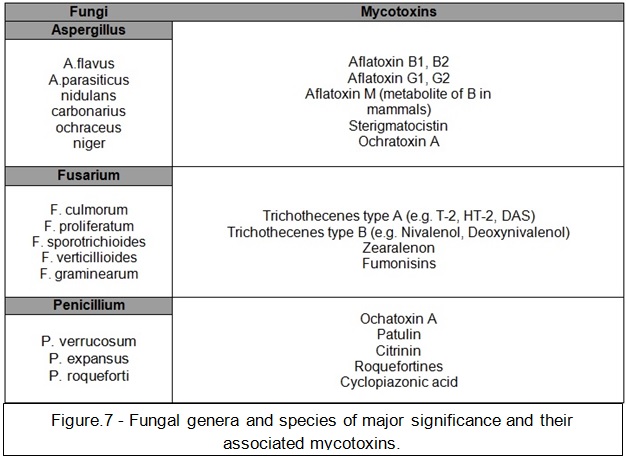

Mycotoxins are not easy to neither classify nor define, considering their various chemical structures, biosynthetic basis, biological impact, and the fact that mycotoxins are created by numerous varieties of fungal species. The way they are classified indicates the scientific background of the person undertaking categorization (Bennett and Klich, 2003). Clinicians commonly classify them by the organs they attack, therefore mycotoxins, in this example are arranged as hepatotoxins (destructive to the liver), nephrotoxins (toxic to the kidney), neurotoxins and immunotoxins (Smith et al., 1995). Cytologists prefer to group them as the following; teratogens (causing abnormalities in physiological development), mutagens, carcinogens, and allergens; while organic chemists categorise mycotoxins by their specific chemical structures: lactones (a cyclic ester) and coumarins (a fragrant organic chemical compound extracted from the tonka bean). Biochemists tend to group them following their biosynthetic traits; that includes polyketides (secondary metabolites), amino acid-derived, etc. At last, physicians categorize them by caused illness (e.g., erysipelas aka St. Anthony’s fire or similar, stachybotryotoxicosis) (Bennett and Klich, 2003) (see Fig.7).

Hsieh (1988) points out that in order to prove that an infection was caused by mycotoxicosis it is essential to find out a dosage to reaction correlation between mycotoxin and the infection, especially among big population where this relationship involves epidemiological research and observation. While conducting environmental observation, food, air and other relevant samples are measured for mycotoxin levels. In case of biological observation, researchers are looking at any residues, metabolites or adducts of mycotoxins present in fluids, tissues or excretions (Hsieh, 1988).

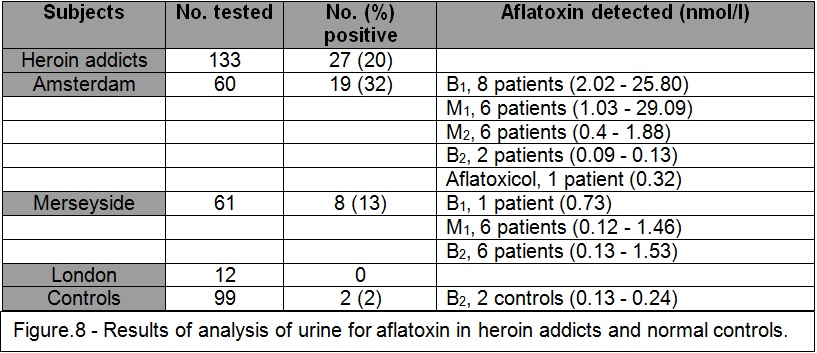

Hendrickse’s (1997) research in Africa in the 80’s suggests that an aflatoxin can take part in pathogenesis of the Kwashirkor disease. Kwashirkor is an invasive type of childhood protein malnourishmentidentified by anorexia nervosa, ulcerating dermatoses (skin disorder associated with bacterial growth), oedema and an expanded liver (Krebs, 2009). Aflatoxin (a naturally occurring mycotoxin) occurs at least in 40% of samples obtained from a breast milk of African women. Usually small concentrations of non-toxic by-products of AFB1 (Aflatoxin B1) are found. In some cases discovering a relatively high concentration of toxic AFB1 can lead to explanation of kwashiorkor disease appearing in babies that were breast-fed. Intoxication by aflatoxin develops in less than 30% of pregnant African women, usually transferred in cord blood (Hendrickse, 1997). Furthermore, aflatoxin-induced immunosuppression can account for the extremely destructive course of HIV infections in Africa. Some of the symptoms of African HIV can be analogous with cases of European heroin addicts, where ‘street’ heroin, also contains aflatoxin. Hendrickse’s (1989) research presents that in countries like United Kingdom and Netherlands, around 20% of urine samples taken from heroin addicts, contained aflatoxin (see Fig.8). Research on aflatoxin contamination can help forensic toxicology with establishing links between different batches of drugs or while performing blood tests in order to differentiate between strains of HIV.

A great deal of research is conducted to prove that it is possible of mycotoxins to be involved in infections causing so called ‘sick-building syndrome’.

I. Indoor Air Quality and Sick-Building Syndrome

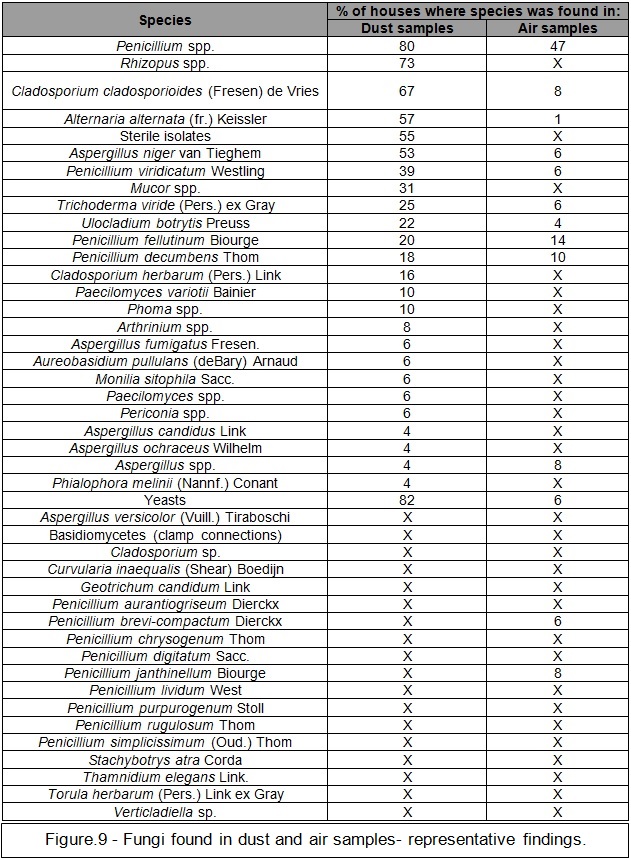

Moulds can gain access inside a household by construction openings prone to air-circulation like ventilation, doors, heating appliances, windows or air conditioning systems (Miller, 1992). Spores (see Fig.9, Miller, 1988) discovered to circulate in the air can accumulate on furnishes, items of clothing, occupants and animals (which can be a secondary factor of outdoor to indoor, mould transfer). Moulds characteristic to indoor environment are: Alternaria, Cladosporium, Aspergillus and Penicillium (Committee on Environmental Health, 1998). Moulds reproduce in environments that include moist, in forms of rooftop leaks, walls, plant pots, or pet urine (Solomon, 1974). Most building materials can provide nutrient sources for fungal development. Cellulose substrates, such as paper products, cardboard, ceiling tiles, wood products, etc. are specifically preferred by certain moulds (Gravesen et al., 1994). Moulds also may colonize near standing water (Kapyla, 1985).

The early research devoted to mycotoxins and their impact on indoor air quality has been conducted by Cole and Hendry (1993) who discussed spores in air-dust that can cause an ochratoxin infection. For example high concentrations of ochratoxin A were discovered in air-dust from Norwegian cowsheds (Skaug and Stormer, 2000) and also have been collected from the inside of a households located in the USA (Richard et al., 1999). In separate research, all of the vertebrates in the infected households including occupants, pets, etc. manifested polyuria (excessive production or passage of urine), a common indication of ochratoxicosis infection in animals; the human occupants were confirmed to suffer from oedema, apathy and a rash on their skin (Richard et al., 1999). There are more symptoms according to O’Reilly et al. (1998), including migraines, nonspecific hypersensitive reactions followed by a peculiar odour and taste sensibility. Furthermore, sterigmatocystin moulds have been discovered in wallpaper previously damaged by water (Nielsen et al., 1999) and on damp carpeting (Engelhart et al., 2002). According to Sorenson et al. (1987) trichothecenes moulds can be expected in aerosolised conidia (asexual spores of a fungus). Inhalation of mould contaminated air can be, potentially, hazardous to health. In the research conducted by Smoragiewicz et al. (1993) T-2 mycotoxin, roridine A, T-2 tetraol and diacetoxyscirpenol were discovered in the dust particles from the inside of a ventilation systems in an office building. Some indoor moulds have the potential to produce extremely potent mycotoxins, also their presence might indicate a long-standing water problem (Burge, 1987).

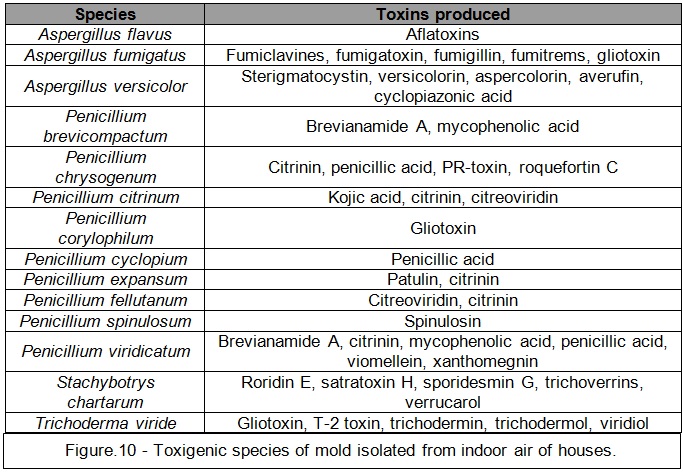

Moulds can exist in a household without realising any toxins. Therefore, proving the mould infection is not consisting of proving the mycotoxin infection. Additionally, despite discovering a mycotoxin (see Fig.10, Flannigan et al., 1991), it is still challenging to prove that they are causing certain animal or human, health complications (Bennett and Klich, 2003).

According to Peltola et al. (2001) mycotoxins can be confirmed as agents responsible for the health symptoms, but the extent of characteristics, consisting of toxic mould exposure, surpass what can be easily identified in terms of typical components of toxin infection. Jarvis et al. (2002) states that more research has to be conducted in order to form an opinion as to the impact on the health caused by inhalation of air in mould-contaminated environments.

The progress in research on mouldy indoor surroundings raised more awareness among scientific community, concerning adverse health issues caused by the release of mycotoxins (Dales et al., 1991).

A high number of residents living in air-suppressed newly build households express deterioration of their well-being that is relieved when they leave the building. The condition has come to be known as a sick-building syndrome (Bennett and Klich, 2003). By widely accepted definition, the sick-building syndrome can be explained as a number of none specific etiological factors, that even when identified, cannot be conclusive. Among those factors the Environmental Protection Agency (1991) lists; insufficient ventilation, cleaning chemicals, and various forms of microbial pollution. Godish (1995) suggests that by identifying etiological agents (like in case of Legionnaires’ disease or hypersensitivity pneumonitis [inflammation within the lung due to dust exposure]), the most suitable term should be named as a ‘building-related disease’. Nevertheless, in popular opinion, sick-building syndrome is often related to the occurrence of toxic moulds, in particular Stachybotrys (Bennett and Klich, 2003).

Concerns about Stachybotrys toxins was initially raised on a large scale after the publication by the Centers for Disease Control (1994) describing eight separate incidents of idiopathic pulmonary haemorrhage (which is a rare lung disease of unknown cause) between newborns in Cleveland, USA. Stachybotrys chartarum was suspected to contribute to the infection. The mould was discovered more often in the households of infected newborns rather than in control households (Dearborn et al., 1999). A case-control research established water damage (general moist and dump environment) and smoking as risk factors for contracting the infant pulmonary haemorrhage (Montana et al., 1997). Further studies resulted in publication of the second report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997) which was more doubtful and concluded that a link between mould and infections cannot be proven at that point (Fung et al., 1998). Despite that, the Committee on Environmental Health of the American Academy of Pediatrics (1998) issued the journal publication describing the toxicity of indoor moulds, cautioning medical practitioners on the likelihood of idiopathic pulmonary haemorrhage being connected to mouldy environments. Cultures of the fungus gathered after the Cleveland case generated numerous, highly toxic macrocylic trichothecenes (Jarvis et al., 1998). Smoragiewicz et al. (1993) decided to analyse cultures of trichothecene mycotoxin using samples obtained from the air condition appliances placed in office spaces. That form of data gathering was considered by the team as the quickest and requiring small founding. Samples were collected from three separate areas in vicinity of Montreal, Canada, which have a previous history of mould contamination. In order to proceed with samples analysis, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was implemented. The team discovered four trichothecenes; diacetoxyscirpenol, roridine A, T-2 toxin and T-2 tetraol roridine. To confirm the finding, high-performance liquid chromatography was used. Smoragiewicz et al. (1993) concluded that the analysis of dust sample can be a preferred technique for identifying the presence of mycotoxins.

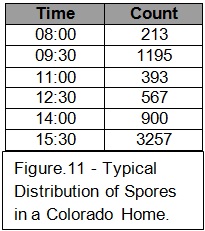

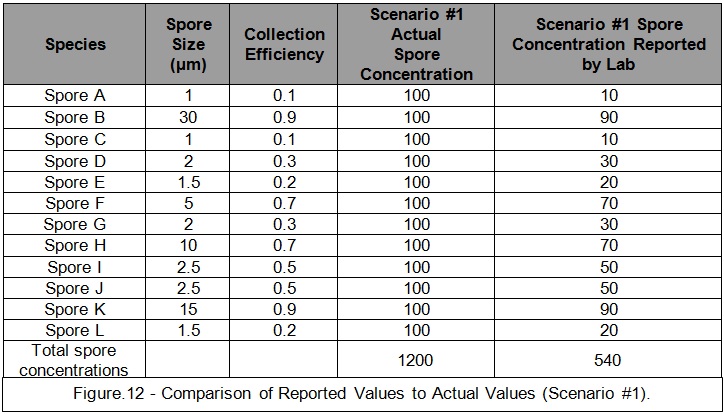

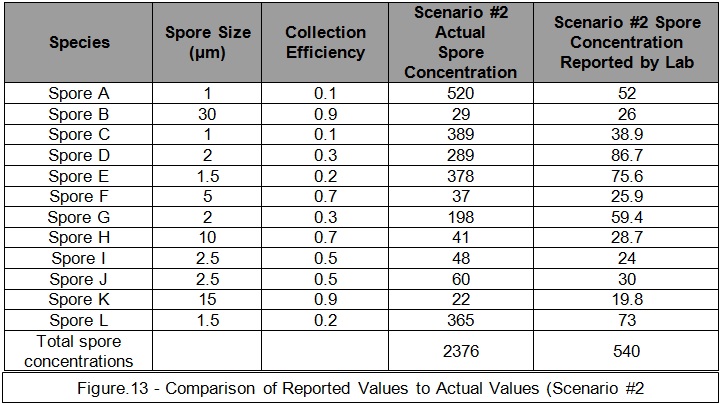

Collected airborne dust samples can prove to be highly unpredictable. Spore counts of airborne fungal entities exhibit a lognormal distribution (a statistical distribution of random variables with normally distributed logarithm) throughout the day (Macher, 1995). Connell (2009) states that variation between one or two samples can be huge and skewed in one direction (see Fig.11). To illustrate this point he used the following scenario; (see Fig.12 and Fig.13) the air in the home contains the spores from 12 different kinds of fungi. Each genus and species produces spores in a narrowly defined size range, so the spores from each species are a different size. But spore concentrations don’t neatly appear in equal proportions; rather, they are present in unpredictable proportions (called a profile).

One study from 2011 (Robertson and Branys) revealed that only 75% of the accredited laboratories could consistently identify Cladosporium, the most common mould in the environment. Furthermore, Aspergillus/Penicillium-like spores, the most common mould category related to water intrusion, were identified by only 50% of the accredited laboratories.

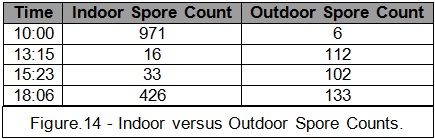

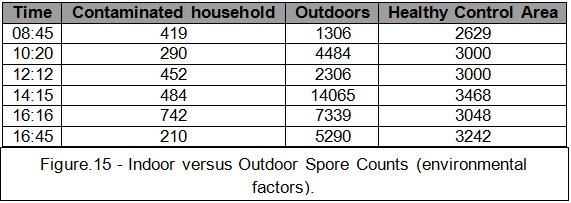

Sample size of a spore collection gathered from the same location (inside or outside), can drastically vary in space of time (see Fig.14, Connell, 2009). Regarding indoor versus outdoor comparison, another factors, like building condition or regional microclimate changes can greatly alter the variations in concentrations of spores between the indoor environment and outdoor environment (see Fig.15, Connell, 2009).

Research conducted by the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) led to creating the Environmental Relative Moldiness Index (ERMI). Using data from ERMI it was possible to establish 36 indoor mould species, which were separated into two groups of fungal species (Group 1 and Group 2). The Group 2 moulds are these, commonly found in most households in low concentrations and are not considered hazardous to health. The Group 1 moulds consist of uncommon species that can cause illnesses in human subjects. Currently 99% of all mould samples are collected from the air (Sobek, 2007).

Although currently there are no procedures for discovering Stachybotrys mycotoxins in human subjects, PCR (Polymerase chain reaction) a DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) analysis technique for establishing the existence of Stachybotrys chartarum was developed (Vesper et al., 2000). Stachybotrys chartarum has been demonstrated to give rise to the hemolysin stachylysin (associated with pulmonary haemorrhage) as its by-product (Vesper et al., 2001). A case-control research analysed 10 newborns that contracted pulmonary haemorrhage against 30 other babies in similar age, which represented a control group, both based in Cleveland (Montaña et al., 1997). Study confirmed that the newborns with pulmonary haemorrhage were those who occupied mould contaminated households (95% confidence interval = 2.6 to infinity) (Committee on Environmental Health, 1998). In contrast to the control group, concentration of Stachybotrys atra fungi was much higher in household of infected infants. Kozak and Gallup (1985) states that Stachybotrys in order to develop in indoor environment requires materials containing cellulose and Hintikka (1977) managed to show that in animals, who were exposed to inhalation of Stachybotrys atra, a severe interstitial inflammation accompanied by haemorrhagic exudates (fluid that filters from the circulatory system) was recorded. Currently fungi (along with number of toxic species) can be found surrounded by damp and moist conditions in many indoor households, although detection of mycotoxins under the same conditions is relatively low. According to Jarvis et al. (1986) it is due to the fact that mycotoxins are not volatile, therefore respiratory infection is believed to be caused by direct inhalation of toxic moulds from the indoor dust. Bennett and Klich (2003) draw the conclusion that due to inexistence of applicable investigative techniques and a scarce number of proven scientific procedures, mycotoxins will persist as diagnostically daunting diseases.

Conclusion

In society today, research opportunities are connected with the theoretical and empirical assessment of the importance of fungal spores. Study of forensic mycology supports further development of fungi as trace evidence, in order to prove a connection between objects, people, and places, and also in the search and location of clandestine burials and body depositions. Much has also been done experimentally on the nature of transfer from palyniferous (producing palynological material) surfaces to objects, fabrics etc., but these concepts are highly theoretical and loosely based on case work (Review of Research and Development in Forensic Science: University Responses, 2011). Future research depends on the further evaluation of case work. As every case requires an individual approach, it is hard to establish the environmental factors leading to transfer of fungi by offenders from specific surfaces. The ability to diagnose and verify mycotoxins is, by far, the most advanced branch of forensic mycology, providing helpful data in subjects of forensic toxicology and forensic medicine.

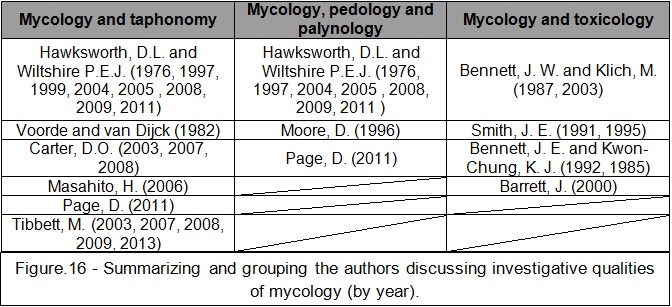

As with any other forensically related disciplines, forensic mycology has to reach for knowledge from different branches of science. While assessing materials for this dissertation a number of names stood out among available research (see Fig.16). It can be noticed that only a small clique of authors directly connects use of mycology with forensic science and its possible investigative qualities. In order to obtain materials to support research in forensic mycology, discovered publications had to be backed up by a number of non-forensically related materials, which can hinder the accuracy of the data. Therefore all of the mentioned authors seem to agree that more research needs to be done, before discussing forensic mycology in definite terms.

Another factor in current forensic mycology is an assessment of minimum times of death by the spread of fungal colonies, grown on the skin and bones of cadavers, as well as clothing and other materials related to them. Preliminary experiments using pig, cow and sheep tissue were carried out. Results which proved to be accurate with the previously verified facts that have been acquired in many criminal cases by Wiltshire and Hawksworth (2010); there is a possibility of devising these standard protocols and experimental methodologies to be used by investigating officers and their experts in post-mortem examinations (Review of Research and Development in Forensic Science: University Responses, 2011).

A further limitation with the current research is caused by the majority of data being obtained just for surface decomposition study (Schoenly et al., 2007), and limited information are available for buried cadavers study (Turner and Wiltshire, 1999) or cadaver analogues (Haslam and Tibbett, 2009). This is often related to the exclusive investigation of entomology associated with cadaver decomposition which typically requires surface exposure (Stokes et al., 2013). It can be concluded that, currently, burial environments are under investigated in relation to forensic taphonomy.

Also through the analysis of plant and fungal fragments in various parts of the pig’s gut it was possible to establish time and cause of death. There is particularly insufficient data, even in medical research, on the times different plant and fungal fragments are retained in various parts of the gut during passage through it; sufficient data could be acquired through better collaboration with pathologists performing autopsies. Although obtaining permissions for such examinations can prove to be difficult. Furthermore there are no guides illustrating, microscopically, fungal materials at different stages of digestion which would be extremely helpful as experiments may be developed and performed in order to document the microscopic characteristics of harmful fungi (including those that are prohibited drugs, such as psilocybin) at different stages of digestion as an aid to their recognition in post-mortem samples (Review of Research and Development in Forensic Science: University Responses, 2011).

The other issue preventing development of forensic mycology methodologies and collection of data is the fact that there are no formal international organizations or professional bodies concerned primarily with that particular area of mycology, although there are single specialists dealing with other aspects of palynology and mycology (in UK mainly, collaboration between Wiltshire and Hawksworth).

There are significant advantages of forensic mycology; unfortunately a debate on its future development requires active participation of scientific world. Currently there is not enough of sufficiently ground-breaking mycological research in a theoretical sense to be further (financially) supported by the UK Research Councils.

In a number of particular cases the police force may fund a small research project to assist in its resolution, but nothing involving high expenses due to recent budget cuts.

The major obstacle for the advance of forensic mycology is an absence of a body with funds allocated for research in forensic science that can finance projects either short- or long- term.

Paper on Review of Research and Development in Forensic Science: University Responses (2011) also highlights concerns as to the poor quality and irrelevance of much research carried out in UK universities and institutions which is labelled as “forensic”. Most research designed as student projects have limited spectrum of analysis (if not theoretical then definitely empirical). Another factor emphasizing poor state of university level research (when it comes to forensics and mycology) is that the commissioned research is not properly supervised or planned by staff that have actual court-room forensic experience. This is especially alarming as this indicates that public resources have been frequently allocated to be spend on research of arguable scientific importance when more relevant investigations could have been developed. Unfortunately, numerous poor quality research does eventually get published in peer-reviewed journals therefore giving them some credit of scientific value. However, studies publicised in a peer-reviewed journals should never be taken as proof of scientific rigour per se as the whole structure relies on the expertise of the peer reviewers. As aforementioned there is currently an insufficient number of professionals the domain of forensic mycology. Most of the present studies in the area of mycology are not concentrated on well-defined forensic issues as they are mainly theoretical concerns. Testing them in practice is more than universities or any police station can afford to do so. Review of Research and Development in Forensic Science: University Responses (2011) inevitably draws a conclusion that such studies could never be acceptable because of the inherent variable nature of the environment, the mechanics of transfer, the highly unpredictable nature of offenders and due to the highly erratic nature of environmental trace evidence and its taphonomy.

Even though forensic mycology (combined with palynology, pedology and taphonomy) might not currently provide a sufficient expertise that would be accepted in the court of law, there is still a good chance for further development of mycology in the realms of forensic toxicology.

The future of that sub-discipline of forensic science mainly depends, not on the quality of the currently provided research (which is sufficient), but on the involvement of governmental bodies and members of private sector in order to found any forthcoming developments.

This work has managed to assess the current level of knowledge relating to forensic mycology as promising but somewhat speculative in terms of research quality. So far forensic mycology is being based on the experience of small number of practitioners, yet while maintaining an existent trend in numbers of related publications growing in space of last 50 years and police forces starting to appreciate and ask for mycologists in order to help with forensic assessments, the world of science can witness the expand of forensic mycology.