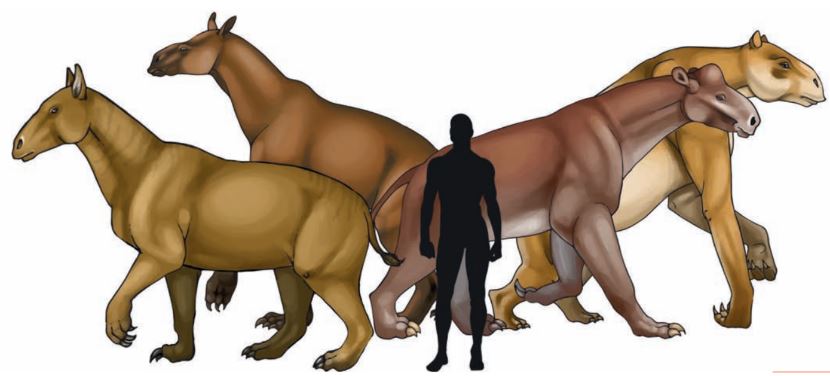

There are many odd and diverse looking extinct mammals out there, and one is the Chalicotherium. A relative of horses, rhinos, and tapirs, they resembled a strange mix of ground sloths, horses, and gorillas which walked on their knuckles. Despite the chalicotheres looking so strange they were incredibly successful – from 46.2 million years ago to just 781,000 years ago the chalicotheres could be found across North America, Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Chalicotherium was the first to be discovered, so the family were named after them.

Discovery and Fossils

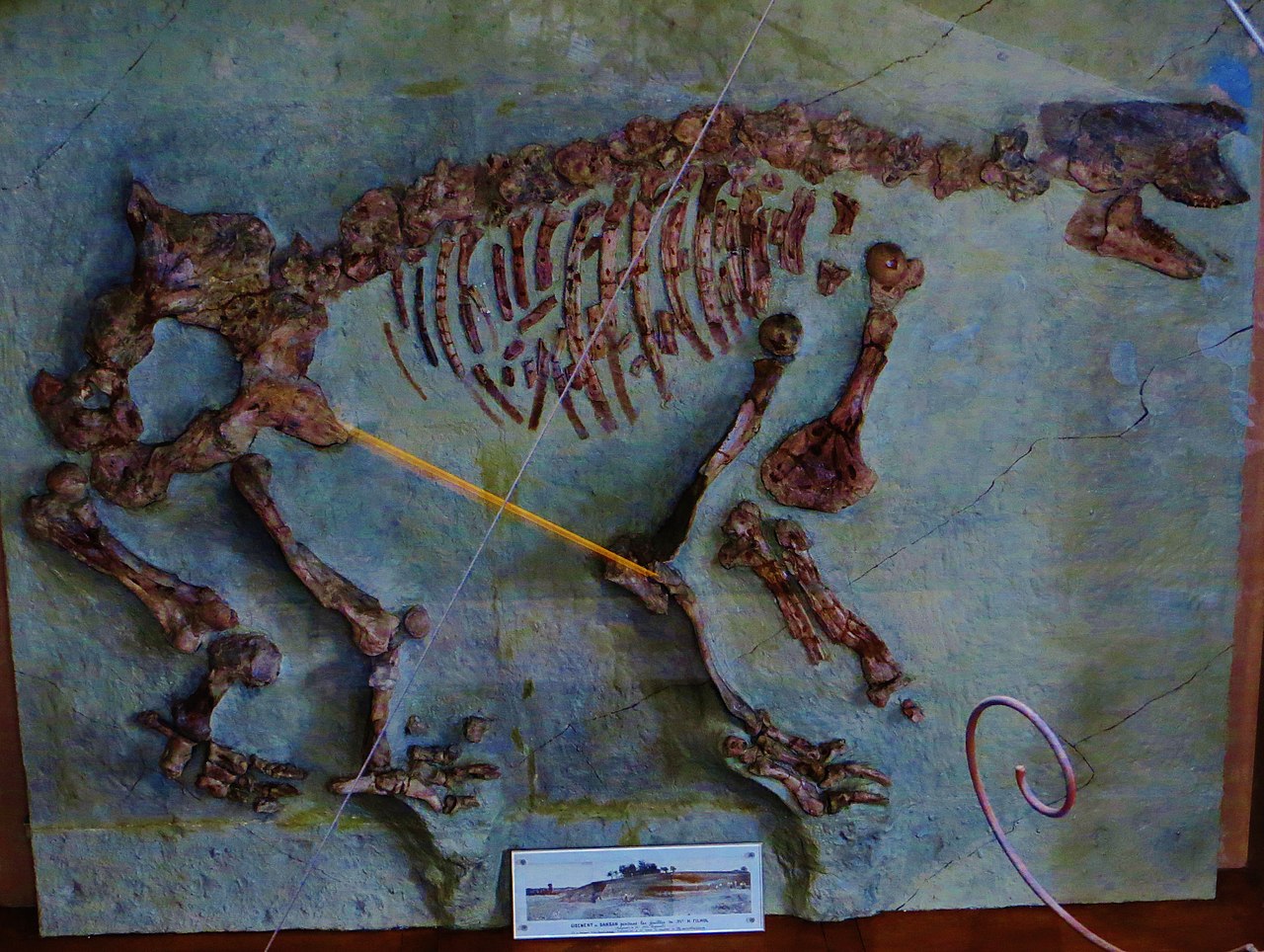

Chalicotherium was first discovered by German palaeontologist Johann Jacob Kaup in the Rhineland, Germany. At first, the teeth were the most iconic part of the animal found, so Kaup named the animal Chalicotherium or ‘Pebble beast’ as its teeth resembled pebbles. The type species was given the full name Chalicotherium goldfussi, but for a while it was only known by its teeth. Then in 1837 French palaeontologist Edouard Lartet in southwestern France discovered its limbs, however, he believed it belonged to a different animal which he named Macrotherium. Further discoveries found that Macrotherium was actually Chalicotherium. Over the course of the 1800s and 1900s Chalicotherium fossils were found across Europe, Asia, and Africa – many being found in China and Mongolia – accounting for eight species. Some, however, are classed as dubious and could be members of other species. There are many Chalicotherium remains coming from three separate continents, so we know this animal fairly well. In Slovakia, over 60 remains were found in one area, for example.

Biology

Chalicotherium and chalicotheres belong to an order called perissodactyls, or the odd-toed ungulates (hoofed mammals). Today this order is very diverse consisting of horses, tapirs, and rhinos, but it was once even more diverse. Other than the chalicotheres, there were the rhino-like giant brontotheres, and also the extinct members of modern families – like the Paraceratherium, the second-largest land mammal in history which was a rhino which rivalled dinosaurs in size. The chalicotheres first appeared in the Eocene epoch around 46 million years ago; during this period mammals became incredibly diverse. Some families and orders would vanish, others would develop into the ones we are familiar with today. Coming from the same ancestor as horses the chalicotheres evolved their unique design which resembled the structure of gorillas, giant pandas, and ground sloths. With a head resembling a horse, very long forearms, and squat rear legs they certainly resembled these animals. In the 1880s palaeontologist Henri de Filhol realised that sets of curved claws, initially believed to belong to a pangolin or anteater, were the front claws of Chalicotherium. This creature walked on its knuckles so its claws wouldn’t be damaged.

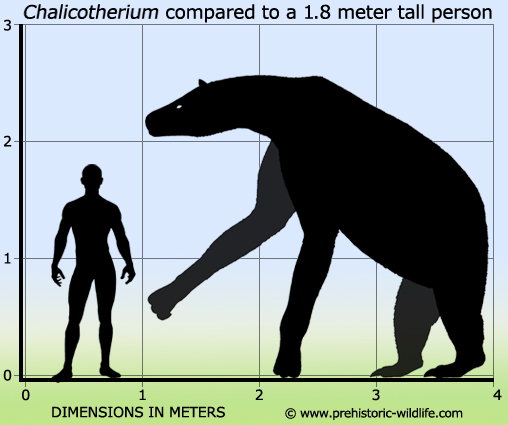

How did this animal live then? Chalicotheres like Chalicotherium were found in forests, and would be quadrupedal while on the move. Pointing their claws inward to limit damage they would walk on their knuckles. Their claws could be used for defense, but they were mostly used for feeding. Like a panda or gorilla, Chalicotherium would sit on its short rear legs, and use its long arms to reach tree branches. The claws would be used to better to grip branches and strip them of leaves. One theory once argued that their claws were used to dig up roots and tubers, however a lack of wear and strain on the claws rules this out. Chalicothere teeth are adapted to a vegetarian lifestyle. Young Chalicotherium had incisors and canines to snip through vegetation, but in adulthood they were shed leaving just the molars to grind up vegetation. Donald Prothero has suggested that they had a prehensile tongue like a giraffe in order to better grip vegetation. Walking with Beasts has suggested that their molars encouraged a diet consisting of shoots and young leaves, but more recent research has found that twigs would also be part of their diet. Although not as tall as giraffes, they were large. At 2.6 metres (8.5 ft) from the shoulder they were tall, and they were likely muscular animals. This did have a downside – they were slow.

When and Where

Chalicotherium was spread across three continents – Asia, Africa, and Europe – ranging from Slovakia to Mongolia to India. The Chalicotherium managed to become adaptable as a genus, hence the number of species across the world, as it lived in a shifting climate. Chalicotherium first appeared at the end of the Oligocene epoch, around 28 to 25 million years ago, when the dry climate began becoming cooler as continents moved closer to their present position. As a result, grass diversified and started replacing forests leading to a new form of habitat – the grassland. Herbivores had to quickly adapt and when the Oligocene gave way to the Miocene around 24 million years ago grasslands had established themselves. The formation of the Alps and Himalayas helped cool down the global climate creating optimal conditions for the development of grasslands. Chalicotherium had to adapt quickly, especially as grass was harder to digest, so it became suited to living within forests to avoid competition. Even then, they could take advantage of the few trees found in grasslands. The Chalicotherium vanished at the end of the Miocene when global temperatures continued to drop allowing the emergence of new grasslands which shrunk the available forests, somewhere between 11 and 5 million years ago. While it spelled the end of Chalicotherium, it did not spell the end of chalicotheres. New chalicotheres, like the African Ancylotherium, adapted to the grasslands until they vanished 781,000 years ago.

Life of a Chalicotherium

Chalicotherium would have lived in forests or along their edges – the Oligocene and Miocene in Afro-Eurasia were dominated by scrublands and emerging grasslands so they had to adapt to living on the edge of habitats. It is unknown how sociable Chalicotherium was – the 60 found in Slovakia were initially thought to be one large herd. However, it is now seen that it was more likely individuals, or small groups, falling into a deep crevice which killed them. Perissodactyls have a wide range of social groups ranging from solitary – like black rhinos – to forming seasonal giant herds – like zebra. Chalicotherium quite likely were either solitary or lived in small groups; this is fairly common with a variety of perissodactyls today. During mating season males would challenge each other, their claws being a potentially damaging weapon if one suitor did not back down. In regards to predators, an adult Chalicotherium did not have much to fear. Being incredibly large, muscular, and armed with strong claws, it meant that an adult was hard to take down. Although over a wide area Chalicotherium was a fairly rare animal – on a prehistoric safari you would not be guaranteed to spot one. There were potential predators – especially for young, old, sick, or injured chalicotheres. Cats and dogs were just arriving on the scene when Chalicotherium was around, and instead the top predators were large, cat-like, dog-like, (or cat and dog-like) carnivores. These included the Hyaenodon or the so-called ‘bear dogs’, by the end of the Miocene they would be replaced by cats and dogs.

The sources I have used are as follows:

- Tim Haines and Jasper James, The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life, (London: 2006)

- Donald Prothero, The Princeton Field Guide to Prehistoric Mammals, (Princeton: 2017)

- ‘Chalicotherium‘, Prehistoric-Wildlife.com, [Accessed 31/07/2020]

- Walking with Beasts, (2001), BBC, 29 November

- Liu Yan and Zhang Zhaoqun, ‘New Materials of Chalicotherium brevirostris (Perissodactyla, Chalicotheriidae) from the Tunggur Formation, Inner Mongolia’, Geobios, 45:4, (2012), 369-376

- Henry F. Osborn, ‘The Ancestry of Chalicotherium‘, Science, 19:484, (1892), 276

Thank you for reading. For future blog updates please see our Facebook or catch me on Twitter @LewisTwiby.