Review Article |

|

Corresponding author: Ronald H. Petersen ( repete@utk.edu ) Academic editor: Thorsten Lumbsch

© 2022 Ronald H. Petersen, Henning Knudsen.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication.

Citation:

Petersen RH, Knudsen H (2022) Jakob Emanuel Lange: The man and his mushrooms. MycoKeys 89: 1-86. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.89.79064

|

Abstract

Jakob Emanuel Lange (1864–1941), Danish mushroom taxonomist and illustrator, was an agricultural educator and economic philosopher. A follower and translator of the American Henry George, Lange was Headmaster of a “Small-holders High-School,” which served as a model for American folk-schools. Lange visited North America on three occasions. The first, in 1927, relied on his professional expertise; the second, in 1931, was purely mycological; and the third, 1939, was a combination of the two. All of this was lived against two World Wars and the Great Depression. This paper summarises the circumstances of Lange’s life against a background of the American mycologists of the day, the ominous events over his adult lifetime and his magnum opus, “Flora Agaricina Danica”, of five volumes illustrating ca. 1200 species on 200 coloured plates.

Keywords

Biography, mycologist

Chapter 1. Introduction

The year was 1927. Henry Ford was wrapping up production of the “Tin Lizzy,” with 15 million on the road. With US population nudging 115 million, that was roughly one car for every 14 men, women and children, to say nothing of other companies and brands. The model T had leaf springs but no shock-absorbers and with few paved roads, automobile travel, like history, was a bumpy ride.

The United States was flexing its muscles. The era of Robber Barons had led to economic and financial strength. Names like John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Ford, Andrew Mellon and Andrew Carnegie resonate to the present day. Teddy Roosevelt had not only changed the view of the country regarding its “infinite” land holdings, but had taken on the monopolies and their lack of regulation. Railroads connected the coasts and carried the raw materials and finished products of the “Second Industrial Revolution.” The backbone of major industry, mining and manufacturing - factories, steel, logging and coal mining – was matched by budding technology, such as typewriters, cash registers and adding machines transforming how people worked. Ford had introduced the “assembly line”. The economic explosion included not only industrial growth and urban expansion, but also growth in agricultural technology, such as mechanical reapers. In a tiny corner of this juggernaut was the transfer of agricultural research in plant pathology into the hands of farmers (

In a time of great expansion and fewer regulations surrounding wealth and business practices, circumstances were ripe for the rise of a class of extremely wealthy individuals who composed a very thin veneer of society. They wielded the power and means to create opportunities and jobs for the working class, but often with little regard for “workers’ rights” issues, such as discrimination, exploitation, workplace conditions and low wages marked the era. Interclass battle lines were being drawn.

In spite of this disparity and inequality, at least the United States did not have to deal with royalty. This was not so in Europe. For centuries, Europe’s social structure had revolved around the royals, the clergy and favoured mercantiles. The peasants remained poor and at the service of their local authority. Only the scent of the Enlightenment sought to provide some relief to the underclasses. Such movements, of course, were not supported by the ruling class and, while the cast of characters differed from that in America, the basic parameters of the social structure were similar. For Europe, the tableau played out in the 19th century, for the United States, the 20th.

In the far-off Denmark of 1927, a modest farmer/teacher/politician named Jakob Emanuel Lange (2 April 1864–27 December 1941; Fig.

Born in 1864, Jakob Lange was a child of war. His father, M.T. Lange, was a vicar living in disputed territory between Germany and Denmark. His strong alter-interest was botany and, in 1858, he penned the first local flora, “The Flora of the Southern Funen Archipelago” (

As a footnote to the turmoil in Europe during the mid-19th century, in 1849, a new Danish constitution tempered the absolute rule of the Danish monarchs. In 1850, after a 2-year revolution, the southern provinces of Schleswig (a Danish duchy) and Holstein (a German duchy) seceded from Denmark and allied themselves with their German-speaking neighbour to the south, Prussia. A decade of turmoil ground on, pitting neighbours against neighbours, a conflict which would harden both Danish and German nationalism, profoundly instrumental in the Rev. Lange’s attitudes about life and education. In 1862, M.T. Lange became vicar in Angel [bordering Germany], but, because he did not want to work for the German cause, he was sacked by the Germans in 1864 and had to flee to Flensborg [further north, in Denmark] and there, during the escape from Germany, Jakob Emanuel Lange was born (

As a young man, Jakob Lange became interested in botany, working as a gardener in high-profiled gardens and going to England (Kew) and Paris (Jardins des Plantes) for two years (1885–1887). Upon his return, he accepted a job as teacher at “Dalum Landbrugsskole” as a master gardener, although without formal education. The job was for four months, but he stayed 30 years. “It soon turned out that Lange had extraordinary abilities as a teacher; he could talk, he had no problems in visualising subjects and teaching was fun for him. His route in life was now on track and it was teaching/education in which he worked through the largest part of his life” (

“During his time in England, Lange heard about Henry George[1] (Fig.

“Already in his youth, through his father, [Jakob] Lange had received impressions about the popular and progressive thoughts about schools, a movement which grew in the middle of the 1800s. His father eagerly supported the small ... free schools which had been founded on Funen [a small island on Denmark’s east coast; also known as Fyn] in the 1860s and 70s, and through this, [Jakob] Lange early became aware of “small-holders’” social conditions. His attitude toward the popular context was further supported by being together with his father-in-law, free-school teacher Knud Larsen. In this way, he soon came in contact with the Danish small-holders movement and this led to his appointment as principal of “Fyns Husmandsskole”. In his leadership of this school, he enjoyed invaluable support from his wife, Mrs. Leila [Larsen] Lange (1884–

As adjunct to his participation (and subsequent teaching position) at the Dalum school, Jakob Lange also became prominent in social and political movements, over time becoming a leader of the Danish Social Liberal Party [now Det Radikale Venstre]. In 1914, he was asked to assume the superintendence of the “Husmandsskole” (“Small-holders’ school”) in Odense near Dalum on the Island of Fyn (aka Funen). He refused, professing that he was comfortable at the Agricultural Folk High-school, but the invitation was renewed in 1917. “The Great War” was at its height, Denmark was neutral and this time he accepted.

Jakob Lange was multidimensional (

Jakob’s first invitation to visit the United States had come in 1914. The fateful assassination in June of a second echelon royal lanced the abscess of ill-will in Europe and before the summer’s end, war was spreading. For America, “The Great War” (World War I), as it expanded across Europe, seemed distant. As

However, what was “the Danish situation” about which he was to speak to the American teachers organisation? Surely not Danish In the mid-1800s sketched above, there was little movement towards equality of society by the peasantry. It was only from 1788 that farmers were freed of their attachment to the nobility, i.e. they could now live wherever they wanted. Against this grain, Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783–1872; Fig.

Although founded before Lange’s leadership, the Odense Folk High-school (Figs

Widowed in 1919, Olive Dame Campbell (1882–1954) had carried on the work of her husband, John Charles Campbell[3] (Fig.

Lange’s sincerity of feelings was shared by Mrs.

Democratic (with small “d”) principles permeated the Odense school. “Mr. Lange told us that a committee of seven met yearly, when necessary and could dismiss the principal on six-month’s notice. Five of the committee members were from Fyn, two being selected by former students. The chairmen of the organisations of Sjaelland and Jylland are ex officio members of the committee, but did not take an active part in the management. Mr. and Mrs. Lange got the same salary and board regardless of whether the school was prosperous or not, an arrangement which left them much freer than as if they had the burden of private ownership. They were not likely to be dismissed or interfered with unless they should become violent reactionaries in politics or radical opponents of religion, in which case ‘we would ourselves undoubtedly wish to leave’. … A combined cultural and practical program calls for a skilled and expensive staff”.

[Experts from the Agricultural College taught at the Folk High-School in the winter, when they had spare time from regular duties during the growing seasons.] “The Forstander (Superintendent) can engage whom he pleases. … The school also owns a large farm, run solely for school support although on demonstration lines. It is in the charge of one of the old students, a trained farmer. Each year, five new graduates are given the much-prized opportunity of working there for the practical training. They are permitted to remain only one year, with the exception of the cattleman who stays longer.

[The school] “stood firmly on the two essentials, family life and the relationships of equals. … The relationship of equals was certainly well-maintained at Odense”.

The durability of the Grundtvigian folk school is testified by Danebod, a small neighbourhood in Tyler, Minnesota. This tiny Danish enclave was settled in 1885 and, almost immediately, a three-storey brick building for the school was built. For more, see bibliography under

Danebod Folkschool building. Source: Danebod.com.

In 1924, the Social Democrats became the largest party in Denmark and took the reins of government. The large Left Party (i.e. the liberals) suffered internal strife resulting in a division between the larger group, which adopted a moderate liberal attitude and a small group whose direction inclined to a more radical liberalism. In both parties, the rural population was the fulcrum, but farmers and small-holders were found in both (

So to the question of “the Danish situation” over which Lange was to expostulate in the United States in 1915 (the invitation of 1914): it could have been political parties in Danish politics, the Grundtvigian folk-school movement, agricultural education in Denmark or Danish professed neutrality in the growing war in Europe, in all of which Lange had more than passing expertise.

Chapter 2. 1927

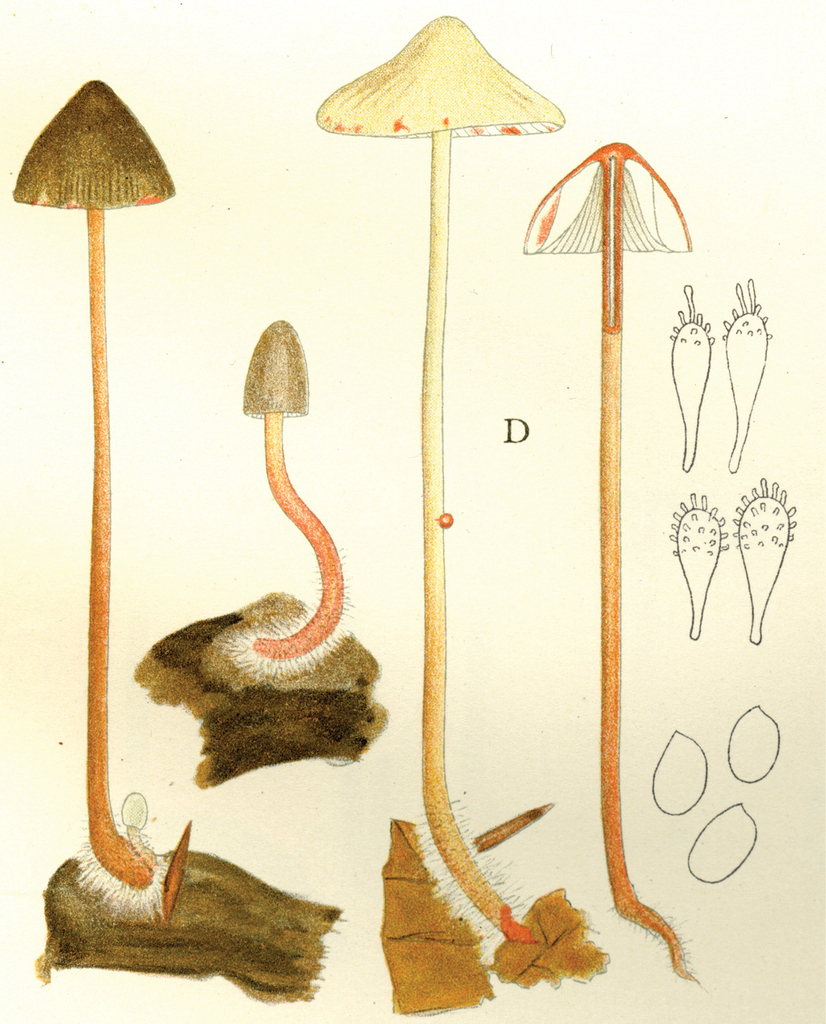

In 1914, the same year as the first invitation to visit the United States, Lange began a series of published studies on the mushrooms of Denmark – with text in “understandable” English! – sometimes accompanied by montages of his own watercolours of the species involved (Fig.

Two principles undergirded the “Studies” project. First, a thorough study of the agarics of Denmark had not yet been accomplished and no one was more familiar with them than Lange. Accordingly, the series furnished keys and descriptions and, where necessary, illustrations, including occasional coloured plates. Second, with the polyglot of language across Europe and Danish certainly minor amongst them and with the larger mycological community of Great Britain and the United States sharing a single language, English was preferable.

Lange was already obsessed by the notion of “agaric richness.” Starting with the first in the series, Lange’s own tally of Danish species numbers was compared to counts of Fries’ species of the same genus.

Lange[4] (1931): “It was an extremely interesting travel, very different from the American travels other [Danish] high-school men had taken in preceding years. For them, the main purpose was to visit the Danish small villages and religious circles, especially in ‘the Middle West,’ the States to all sides with Chicago as the centre. My travel on the contrary went through the old States, the East coast, from Maine to North Carolina and only at one point to the west, passing Niagara to Lansing in Michigan. And we did not see many Danish. On the contrary, we received a much varied and quite in-depth impression of the Americans, far more comprehensive than the Danish high-school people normally got, even after many years in the US.

“The ’Aquitania’ was one of the largest swimming monsters of the time, with seven decks. But a sailing trip across ’The Pond’ was anyway not very exciting: remarkably few ships are met with on the route. Days may go by without seeing any. And then when you finally reach the harbour in New York: passing the Statue of Liberty, the light of which, according to malicious tongues, is only shining outwards, not over America, the symbol of which she should be.” This observation on societal inequality, among other experiences, was a reaction to the United States’ Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, known as “The Immigration Act”. It restricted immigration to 2% of the number of nation-immigrants from each country, measured by the census of 1890. Asians were prohibited totally.

“After Medical Control [on Ellis Island, the reception centre for immigrants for decades] and other modern plagues, we finally came to the city and saw the ’skyscrapers’ of Manhattan in front of us. The strange thing about these is that it was a BEAUTIFUL view. The reason is probably their sky-striving character (the one they share with the old Cathedrals, with which they have a certain resemblance in my memory). It is almost as if all the Cathedrals of the World have decided to meet here. And add to this their functionalistic appearance, a feeling of ’problem solved’- mathematically correctly. In this way, it is possible, under narrow area conditions on stony ground, to build a business town for a million population. But it was strange, when you walk around in the narrow streets, which felt like the bottom of huge canyons, to see amongst them an old church, with a tower which was impressive for its time but now looked like a small, sleepy candle-snuffer, hardly reaching 1/3 towards the top of the skyscrapers from its small green churchyard in the centre of a large city’s stone desert”.

“The congress in Lansing, the capital of Michigan, took place in beautiful surroundings, at this state’s agricultural high-school [later renamed as Michigan State University]. Everywhere in America, universities – and even smaller schools – are surrounded by large parks with very old trees of beech, elm and maple and the buildings are usually large, wonderful and dominating.

“One of my best days was when I spoke to a thousand-fold audience of farmers from the area. It was almost like being home at the agricultural school to a camp – only that here there were loudspeakers and other devices at that time unknown in Denmark and a huge orchestra of about 50 musicians. ... We also had curious experiences, like at a ’Rotary’ lunch, which was very American and took place in a large hotel in Lansing. My wife and I were, of course, placed at the head table with the other guests of honour: to the left the beauty queen of Michigan (with her mother and fiancé), to the right ‘the world champion mouth-organ player!’ I had the triumph that I, although handicapped in the competition, could spell-bind the busy businessmen, who here had a short schedule, by my story about the Danish cooperative movement– for even more than 20 min, which was said to be a “record”.

“At the meeting/camp in Williamstown [Williams College, Massachusetts], the old conservative university in Massachusetts (where female students were not allowed), the atmosphere was somewhat different, more upper class. It was very international. A dominant role was taken by the young H. A. Wallace[5] – now [written in 1938] known everywhere as Roosevelt’s secretary of agriculture and legislative active administrator. The British foreign-press chief talked (about England’s economical policy in China); a former German Reich’s finance minister shed light on Germany’s economic policy after the war [World War I, reparations] etc. And here I was to talk about something so small in a world context as Danish farmers. Was it likely to be of any interest? – It was a hall the size of the Copenhagen cathedral, but luckily there was a loudspeaker – and [the talk] was OK; at least the Italian Count Sforza hurried up to my wife after the lecture and kissed her hand as a thank you: what else can you ask for? By the way, they had changed the title of my lecture. I had called it ‘Progressive Peasantry’ (farmers in an era of progress); but it was changed to ’Agricultural Progress’. Why, I asked? And received the answer that ’peasant population’ and ’progress’ were mutually exclusive - two items which could not be thought of as being related. That gave me a lot to think about.

“I shall not count the different agricultural high-schools and universities we visited during the tour. When we had the laborious tour behind us, we could with a good conscience go to Mrs. Campbell in ’the mountains’.

“While most of the villages in the southern states are ’Black,’ there is a population in the Allegheny Mts. valleys which is, for America, an unusually clean and pure English-Scottish race. These mountain people constitute a ’tribe’ of their own. They are descendants from an early immigration to the North Carolina lowlands, but were later forced by mass immigration from Europe into the valleys in the mountains, where they settled, whereas the other immigrants continued across the [mountains] and into Mississippi. Now they constitute a peculiar farmer-people, extremely old-fashioned, speaking practically what you would call an old-English dialect, living from pieces of old poems, homemade, traditional art-work etc., but now [find themselves] in [a general] explosion and dissolution, along with the arrival of modern central schools: highways form a net of modern culture into the valleys of the theretofore almost roadless valleys’ quiet life.

“It was among these farmers and small farmers that Mrs. Campbell saw that the high-school had a mission, as already mentioned. Now she had come so far that her own agricultural farm was not alone in exemplary order, but she had founded a co-operative dairy, organized co-operative buying etc. and also in a modest way started the school. And now finally the first real house, the assembly hall made of timber-logs was finished and it was for this celebration we were invited. A lovely room, with mat brown waterboards on the walls and homemade chairs instead of benches, one from each home in the village.

“It was curious to see the population coming from near and far in their delicate [horse-drawn] chariots with picnic-baskets, babies etc, almost as you may imagine the [Danish] ’sky-mountains parties’ (the highest point in DK is 189 m) in the old days of Blicher [a Danish poet depicting country life]. The speaker following me was President Hutchins from the Peoples’ University of Berea[6] in neighbouring Kentucky (

“From North Carolina, we headed for New York. Before we sailed home, we had the opportunity to participate in a Henry George gathering. It was interesting to meet men, whose names were well known to me from the information and agitation work of George’s ideas through many years. The person I had the most living impression of was Hamlin Garland, whose collections of short stories (“Main Travelled Roads” from the 1890s) was the first who gave a ’living picture’, based on a realistic social background, of the American country population’s life and thinking. The most direct connection I had, however, was by meeting Mrs. Anne George de Mille, the youngest daughter of Henry George, who is fully occupied with the continuation of her great father’s ideas among the people of our day. At the congress we, by the way, had the impression that this was needed. The audience was mostly old people, but fortunately Mrs. de Mille and other younger people’s efforts now seem to be fruitful among the younger people.

“The most important of the veterans from Henry George’s own time, Louis F. Post[7] and his wife Alice Thatcher Post were not present at the [Lansing] congress, but we got a very living impression of them in their home in Washington [DC]. They are now very old but fully engaged by all the important questions of our time. I made them happy by bringing my thanks for their weekly journal ’The Public’ which through many years meant a lot to me by its progressive and bold talk”.

Almost as an after-thought, Lange mentioned a couple of mycological oddities he saw in the wilds of far-western North Carolina. The first (

“One of the most peculiar cases of parallelism is the existence in America of a phosphorescent form of Panus stipticus. While there is no record, as far as I know, of any phosphorescence in the European form, the American one is renowned for its bright noctilucency [sic]. I myself encountered this phosphorescent form in North Carolina (Cherokee Co.) in 1927. When seen by daylight the specimens were exactly like those so commonly collected in Denmark. Whether the phosphorescence is a real specific difference or can be accounted for by atmospheric conditions (or bacteria) remains to be decided by further investigations”. The local folks were familiar with luminescence, which was known as “foxfire.” Had Lange been present later in the year, he might have seen the “Jack O’lantern” mushroom, Omphalotus illudens, much more impressive than foxfire.

Surrounded by well-wishers as they were on their trip, the Lange’s had little opportunity to experience the exhilaration of city culture, which was in the midst of “The Roaring 20s”. The nation’s economy was growing almost too quickly, leaving the common worker behind. Not only was Prohibition, instituted in 1920, in full swing, but so were its violations. “Speakeasies” were ubiquitous. The Harlem Renaissance included the Savoy and Cotton Club; Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Ethel Waters performed there. The Lindy Hop and The Charleston were popular dances. The “Ziegfeld Follies” dazzled Broadway. The nation was still agog over Charles (“Lucky Lindy”) Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic aeroplane flight in May. American extravagant exceptualism was on display.

With their District of Columbia stop behind them, the Langes sailed for Europe in late autumn, 1927, perhaps to reach Odense in time to celebrate Morten’s birthday. Jakob seemed pleased with their tour, having delivered the message of the Danish cooperative movement and sharing experiences and philosophies with many people of similar views. The movement in the United States was represented by numerous eastern institutions, from colleges to folk schools to dreams in the minds of progressive individuals.

Chapter 3. 1931

As aethereal as the United States economy and society were during Jakob’s first visit in 1927, just so low was the country during his second, in 1931. In October, 1929, the Wall Street bubble burst, the Stock Market swooned and by 1931, there were bread lines across the country. Herbert Hoover (1874–1964) was President, but there were rumbles of disappointment. Prohibition was still the law of the land, but violations were even more prolific than during Jakob’s first US visit. “Shanty Towns” and “Hoovervilles” of displaced workers existed in the squalid shadows of all US cities. Although some of the elite families had lost everything, many others had not and societal stratification was more severe than ever. It was the juvenile stage of “The Great Depression.”

As marginal as mycology had been for Jakob’s prior visit, so his political and cultural ideas were in 1931.

The Mycological Society of America did not exist in 1931 (

“I sent my plan to the leading universities and to my private correspondents in the US and had, in this way, in 1931, planned such small mycological meetings in different areas, at Universities in the states of New York (Cornell), Michigan (Ann Arbor), Canada (Winnipeg), Oregon (Corvallis), at the Department of Agriculture in Washington [DC], in the forest- and lake-camp in the Adirondack Mountains and finally the mycological society in New York. So, it was a rather comprehensive plan, but the Americans were very interested and took good care of the arrangements. The largest approval was at Cornell where mycologists from about ten states (about 50 all told) were summoned and where a large apparatus with microscopes etc. was present and excursions arranged. The whole business had for me the important result that it was living proof of the value of such illustrated works and thus shaped the background for my thoughts of publishing my large mushroom-picture-work [Flora Agaricina Danica], which was realized starting in 1934 (

“The Carlsberg-Foundation and the Rask-Ørsted-Foundation supported my plans and this along with the lecture payments made an economic balance possible, even if we were three, since both Leila and our 12-year-old son, Morten, joined the trip”.

In his English language report (

Lange’s purpose was not only to experience American mushrooms and to share opinions with American experts, but to exercise his concepts of ecology, distribution and taxonomy of both the mycota and flora. He was well-versed in the northern European groups. In his English report of the 1931 trip (

However, did these designations also apply to the mycoflora?

“On the other hand, it is also a well-established fact that the flora of any continent, besides these cosmopolites, comprises an element of endemics: species and even genera, which are exclusively American or European. In the phanerogamic plant world, the overwhelming majority of the species are decided endemics. But what about the mycoflora? Is the main body of the American fungus-flora decidedly ‘American’ or does it consist for a large part of cosmopolitan species which are familiar to the European mycologists of old and, therefore, in common parlance are called ‘European’ species? And finally, are the specifically American species mainly parallels or are we more likely to meet with species which represent other types, widely separated from those met with in the Old World? In other words, is the American fungus-flora chiefly characterized by congruency, parallelism or incongruity?”

An anecdote was inserted: “But stronger and more lasting than any other impression is the evidence of the wonderful cosmopolitanism of the Agarics. When you have once found, in a Danish Sphagnum-bog, a few specimens of the ‘new’ species Stropharia psathyroides Lange, it gives you a shock to meet with the very same plant in a bog in Oregon, near the Pacific Coast and only an hour later to come upon Lepiota cygnea Lange, of which the only known specimens were theretofore those gathered in 1925, a few miles from my Danish home”.

Lange furnished examples of agarics he considered to belong to these categories and, in “Flora Agaricina Danica” (FAD), repeated some of his conclusions (

In America, word spread of Lange’s proposed appearance. Harry Morton

“From August 28 to September 2 inclusive, Doctor Lange will be at Ithaca, N.Y. The region about Ithaca is especially interesting to him because Atkinson published over a period of years on locally collected materials. Fungus forays will be made daily to nearby points of interest in the effort to see a large number of species.

“In order that the conceptions of species as held by Peck, Atkinson, Kauffman and other older American workers in the group may be clearly understood, it is imperative that Doctor Lange be enabled to exchange ideas in the field with their students. To this end, American mycologists, especially those interested in mushrooms, are urged to come to Ithaca and cooperate in making these forays a success. Students with only a minor interest in the Agaricaceae will also be welcomed and the foray will be arranged in such a manner that collecting in other groups will be fruitful. Incidentally, the Atkinson herbarium has been put in good order in recent years and is now available for consultation in the new Plant Science Building at Cornell University.

“Those who plan to attend the Ithaca forays are asked to notify the undersigned at as early a date as possible. Arrangements will be made for lodging, meals and transportation at a reasonable rate. Information concerning these items or other features of the plans for the forays will be gladly given”.

On his previous trip in 1927, Lange had emoted on the New York City skyscrapers, but now in 1931, he must have marvelled over the new Art Deco-decorated Chrysler Building, opened almost simultaneously with the Stock Market crash in 1929 and then soon eclipsed by the Empire State Building some blocks south, opened in 1930. For many later years, they would dominate the city’s architecture for travellers arriving by luxury liners or later by aeroplane.

Before relating Lange’s “study-tour,” it is necessary to acknowledge the clues left in the collections made during his visit which remain in herbaria.

Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts (dates unknown). Lange did not detail a stop at Harvard, but his comments on some of the original mushroom illustrations by Bridgham and Krieger, commissioned by William G. Farlow, attest to his presence. Donald Pfister (1975 & pers. comm.) observed that Lange had access to more than 600 such paintings, from which only 103 plates were composed (

Vermont (18, 19 August). Although several destinations of Lange’s itinerary were anticipated, some were more explicit. An example of the latter was his visit to Vermont. That such a foray actually existed is confirmed by

The family home of Carroll William Dodge (1895–1988: see above) was in Pawlet, southern Vermont. He had studied at Middlebury College and, there, had come under the influence of Edward Angus Burt, who soon moved to St. Louis as Professor at Washington University and mycologist at the Missouri Botanical Garden (

It was the first foray for Lange in the United States and he had not yet established a routine. He took time to make eight water-colour sketches and recorded more than 40 names in his notebook.

Seventh Lake, The Adirondacks, New York (20–25 August). The first widely announced stop on Lange’s itinerary was a select foray in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. Fred Carleton Stewart (1868–1946), plant pathologist at Cornell, had a summer “camp” on a lake-shore in the Adirondack Mountains (Fitzpatrick, 1947;

Years later, in his memory of the affair,

“Lange also brought with him his wife [Leila] and his son, Morten, then about 8 years old [actually 12] and, at that time, he [Morten] knew many of the agaric genera at sight. (Dr. Morten Lange has for some years now been mycologist in The University of Copenhagen [written in 1975]).

“… He (Jakob) was of rather exceptional physique, perhaps 6 ft., 4 in. height, 190 lbs., lean, good humored, a delightful personality, he spoke and wrote excellent English and, as a conversationalist, one of the best. His devotion to the people led him, while here at the foray, to visit the Penland (N.C.) Folk School”. While certainly possible, Lange surely visited the John C. Campbell Folk-school, also in North Carolina.

Cornell University, Ithaca, New York (25–28 August). Although MycoPortal data show a month-long hiatus between the Adirondack foray (26.8.31) collections and those from Corvallis, Oregon (27.9.31), Lange’s notebooks and paintings make the Cornell dates more precise. Fitzpatrick’s announcement of the Cornell event set the dates as 28 August through to 2 Sept. In his post-tour report (

Hesler’s interest in the Adirondack and Cornell forays remains somewhat murky. Before and after his arrival at the University of Tennessee in 1919, he was a phytopathologist, distinctly in the mould of his Cornell PhD under H. H. Whetzel (

Ontario (?Ottawa; dates unknown): The discrepancy between Lange’s notebook dates for Ithaca and those in Fitzpatrick’s announcement may have provided enough time for a side trip mentioned only in passing in Lange’s notebooks. Lange’s described itinerary does not report any time in eastern Canada, but MycoPortal lists a single collection by Lange from Ontario, Canada, Thelephora terrestris, on 16 September 1931 – nearly two weeks after explicit Cornell and well before implicit Vancouver – with no co-collector, but improbably housed at the University of Wisconsin, perhaps a link to a co-collector.

By searching for such a link, though, it might be coincidental that, in Toronto, Herbert Spencer Jackson (1883–1951) had taken charge of the fungus herbarium at the University of Toronto in 1929. He had degrees from Cornell, Harvard and the University of Wisconsin (PhD in 1929) and was a vigorous mycological researcher (

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan: Again, this visit was noted only marginally, but Lange noted the water-colour illustrations in the collection of Dr Howard Atwood Kelly (1858–1943), executed by Lewis Charles Christopher Krieger (1873–1940;

Edwin Butterworth Mains (1890–1968;

Bessie Bernice Kanouse (1889–1969) was also a Michigander through and through. Her B.A. was from the University of Michigan, as was her PhD in biology in 1926. She was appointed Curator of the University of Michigan Herbarium and assistant to the Director, Calvin H. Kauffman. She accompanied Kauffman on at least two collecting trips, but her own interest was in “water moulds,” on which she published (

Notably, Kauffman’s student, Alexander Hanchett Smith (1904–1986) had been obliged to change professors upon Kauffman’s illness and now was being supervised by Mains. Smith’s M.A. was gained in 1929 and his PhD dissertation, “Investigations of two-spored forms in the genus Mycena” earned his PhD in 1933. Conversation with Lange could have been lively. As Atkinson and Kauffman before him had used photography (

Just a few buildings away, Dow Vauter Baxter (1898–1965;

A half-day’s ride from Ann Arbor was East Lansing, the home of Michigan State University. In 1931, Ernst Athearn Bessey (1877–1957) was serving there as Dean of the Graduate School, building its programme in plant pathology, amongst many others. Whether he might have met Lange is unknown to us, but it would surely have been possible. In addition to his Deanship, Bessey was developing his book, “A Textbook of Mycology” (

Minnesota (perhaps also Wisconsin): Although both States were merely proposed, but not further mentioned in Lange’s notebooks, these States had a wealth of Scandinavian settlers and universities with strong phytopathology research faculties.

Lange’s reference to a stop in Minnesota is opaque. One possibility might have been in Minneapolis, where Clyde Martin Christensen (1905–1993) was a graduate student at the University of Minnesota.

The Minnesota Mycological Society was founded in 1899, as the second oldest such organisation in the country (Boston was first, four years previous). For some years, its founder, Dr Mary Whetstone,(8) was corresponding secretary (

Although still marginally known for “pure” mycology in 1931, the University of Minnesota was a juggernaut in plant pathology, especially cereal diseases. By 1931, Elvin Charles Stakman (1885–1979) headed the Plant Pathology Department of the Division of Vegetable Pathology and Botany at the University (

Winnipeg, Manitoba; Longpine Lake, Ingolf, Ontario, Canada (14–18 Sep): Unlike the forests encountered on both coasts, south-central Canada is located at the northern rim of The Great Plains. Although less rich in large mushrooms, careful inspection of scattered large groves of aspen and/or conifers could produce results.

Guy Richard Bisby (1889–1958) was a professor at the Manitoba Agricultural College (later University of Manitoba) in Winnipeg. A South Dakotan by birth, Bisby earned his B.A. from South Dakota State College, his Master’s degree from Columbia University (NY) and PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1918 (

The cabin was actually Longpine Lake, near Ingolf, a short distance over the provincial line in Ontario. There, they lived in a cabin as noted by Bisby. His human side was revealed in a small note by Morten (

Some details of those days can be found in MycoPortal and a search for appropriate collections in the National Herbarium of Canada at Ottawa (DAOM). Arrival in Winnipeg 14 Sep (a Monday), was spent in the town, with some time devoted to a stroll on the campus of Manitoba Agricultural College (with seven collections). It is assumed that the 15th was spent in transportation to the hamlet of Ingolf, about 145 km away; Longpine Lake was nearby. Upon arrival, only three collections were made, but on the 16th, at least 32 samples were collected and, on the 17th, 41. On the 18th, only 12 specimens were collected, but on that day, it may have been necessary to pack and head for Winnipeg.

A couple conclusions may be drawn from these data. First, Guy Bisby was a very organised host. He must have organised a drier and some way to bring at least 96 collections back to Winnipeg. Moreover, these collections were labelled appropriately and sent to Ottawa for deposit in DAOM. Second, in 96 collections, there was not a single duplicated name. Third, aside from four non-agaric fungi, all other collections bear names of mushrooms. Fourth, a rough review of collection labels shows a typical roster of autumn mushrooms, at least further east in North America, dominated by Cortinarius, Lactarius and Russula. Sixth, while all collections bear both Lange’s and Bisby’s names as collectors, there is no notation on the name of the identifier. It is, therefore, impossible to know if the fungi were recognised as “typically European” by Lange or by Bisby as “American” with European authors’ names.

A fellow faculty member of Bisby in Winnipeg was Arthur Henry Reginald Buller (1874–1944;

Although John Dearness (1852–1954) was retired in 1922, he remained active, amongst other contributions, as co-author of “The Fungi of Manitoba” (

Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada (including 21 Sep): Included merely as a mention in Lange’s itinerary, collection numbers 178–183 and 191–195 were recorded. These numbers overlap those from Long Pine Lake, Manitoba. There was time for a “portrait” of Banff (Fig.

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (approx. 23 Sept): In an easily overlooked paper in Mycologia on Vancouver agarics, Jean

Seattle, Washington (dates unknown): The data confirming a stop in Seattle are sparse; only collection numbers 202–222. To be sure, to have missed this venue would have been unfortunate, for it offered potentially excellent collecting grounds.

One of the earliest papers on west coast fungi was

John William Hotson (1870–1957), a Canadian, came to the University of Washington, Seattle, in 1911, like Murrill and soon was teaching several courses, including botany, forest pathology, general mycology and elementary agriculture. His Harvard PhD was granted in 1913. Early in his Washington career, he came into contact with Sanford M. Zeller who later took an appointment in Corvallis, Oregon, as a plant pathologist (Ammirati, pers. comm.) and with whom Lange collected during his 1931 trip.

Hotson organised the first fungus herbarium at Washington and many of his specimens are cited in treatments of Agaricus, Amanita and other genera of agarics.

Daniel Elliot Stuntz (1909–1983;

Perhaps Lange’s visit may have spurred Hotson to put his mycological experience into words (

They also echoed Lange’s sentiments this way: “The genus [Agaricus] is well represented in the Pacific Northwest, but, when one wishes to identify collections made in this region, he faces an obstacle in the lack of available information concerning the local flora and also in the fact that some of the species occurring here are more closely allied to European forms than to those found in the eastern United States. To further complicate matters, the student will often find a lack of agreement among mycologists concerning the interpretation of a particular species and is apt finally to be more confused than helped by the literature he consults. This condition has been found as prevalent in Europe as in America” (

Corvallis, Oregon (approx. 27 Sept): Sanford Myron Zeller (1885–1948) was the mycologist at the Oregon Agricultural Experimental Station (associated with Oregon State University) in Corvallis. His PhD was from Washington University in St. Louis, where Edward Angus Burt was the mycologist. At the time of Lange’s visit, Zeller’s research emphasis was on parasitic fungi, less so on gastroid fungi (

At the University, Helen Margaret Gilkey (1886–1972) was Professor of Botany and Curator of the Herbarium. Her Master’s degree thesis entitled “Oregon Mushrooms,” had led to doctoral work at the University of California and her PhD dissertation, with William Albert Setchell as major professor, was “A revision of the Tuberales (truffle fungi) of California” (Leonard 2021). With this background, she was already a likely contact for Lange, but her talent as an artist-illustrator might well have matched Lange’s insistence on accurate depictions. Lange, however, saw little value in dried herbarium specimens and coloured portraits of Tuberales were less than helpful. They might have differed over this subject.

Berkeley, San Francisco Bay Area, California (visit problematic): Surely, a most conjectural stop for Lange and family was the California Bay Area; San Francisco and especially the University of California, Berkeley. Lange may have seen Edwin Bingham Copeland’s (1873–1963;

A person with a much longer career in Berkeley was William Albert Setchell (1864–1943;

Elizabeth Eaton Morse (1864–1955;

Elmer Drew Merrill (1876–1956;

It must be written again, however, that we have no evidence that Lange stopped in the Bay Area, so his possible interaction with any of the triumvirate of botanical friends is purely conjectural.

Los Angeles, California (dates unknown): Los Angeles appears only as a single-word mention in Lange’s proposed itinerary. The nearest predictable mushroom-hunting grounds were in the mountains away from the coast, but even more improbably, mycologists were also less prolific.

One person with mycological experience and resident in the Los Angeles area was Effie Almira Southworth Spalding (1860–1947;

Born in New England, she attended Allegheny College for a year, but transferred to the University of Michigan, where she was awarded a B.A. in 1885. She immediately became an instructor at Bryn Mawr College, near Philadelphia, on a two-year contract. In 1887, she was hired by the USDA as the third person in the Section of Mycology, along with Erwin F. Smith and Beverly T. Galloway and moved to Washington, DC (

That she was on faculty and could have met Lange in 1931, is beyond dispute, but whether they, in fact, met, is highly questionable. She would have been 71 years old and a foray or two would have been improbable. What was much more expected, however, was that Los Angeles served as the Langes’ terminus along the west coast and their departure point for return to the east.

In 1922, Bonnie C. Templeton (1906–2002) moved from Nebraska to Los Angeles. According to Wikipedia (

Although preceding Southworth by several years, Alfred James McClatchie (1861–1906), a Professor at Throp Institute of Technology (now known as California Institute of Technology, “Caltech”), was an active botanist, including fungi and published two papers which included fungi of Pasadena vicinity (

Also worthy of mention, Charles Fuller Baker (1872–1927;

“Southern states” (Arizona, Kentucky, Tennessee; dates unknown): From MycoPortal, we know that the Langes were in the neighbourhood of Corvallis, Oregon, on 27 Sep. At that moment, however, the monitor goes black and the next time we have a firm date is 24 October, in Washington, DC. Assuming their mode of transportation as rail and Jakob’s reference to “the southern states,” we can conjecture that they took the Southern Pacific route through southern Arizona (Morten found the Grand Canyon “shocking”), New Mexico and Texas. Reference to the specific States appears only in Lange’s proposed itinerary, with no collection numbers recorded or sketches executed.

William Henry Long (1867–1947;

His professional career was at the USDA where he soon was transferred to the Office of Forest Pathology in the Bureau of Plant Industry in Washington, DC. There he found himself in a stellar group of mycologists/forest pathologists. Soon, he was appointed to head up this work in the south-western States, headquartered in Albuquerque, New Mexico. There, he stayed until retirement in 1937. Although his research emphasised tree rusts, he was interested in the gastromycetes and it was probably this that would have caught the eye of Lange. If the two met, possible field work for Lange would have been at relatively high elevation where the pine forests dominated.

From the dry southwest, the Langes would have proceeded through Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia into North Carolina. Hesler’s comment (written in 1975) that Lange visited Penland School in western North Carolina before returning to Denmark, raises the probability that the Langes re-visited the John C. Campbell Folk-school in Brasstown, NC, only some 100 km away from Penland. Unlike the Campbell school, founded along the same Grundtvigian principles as the Danish schools, Penland was, from its beginning in the 1920s, a school of crafts, chiefly weaving, selling the products to supplement the meagre wages of the local population (Craft Revival 2021).

Washington, D.C. (dates surrounding 24 Oct): The Langes (minus Morten) had already seen Washington during their 1927 trip (see above). Their 1931 visit was for very different reasons and now they found a goldmine of mycological activity. The discipline was represented at the US Department of Agriculture, located downtown. The Department had been established in 1862, during the Civil War and within days of the Morrill Act enabling Land-grant Colleges (

MycoPortal reports only three collections, from Glen Echo, a suburb and only collection numbers 252–255 were recorded in Lange’s notebooks.

By 1931, Cornelius Lott Shear (1865–1956;

Vera K. Charles (1877–1954;

Edith Katherine Cash (1890–1992) professed that her only mycological training was a night course at the USDA Graduate School. Nonetheless, her 1912 A.B. from George Washington University in history and languages got her a job at the USDA as a botanical translator in 1913. Over the following half-century, she progressed through the ranks from junior pathologist (1924) to mycologist (1956). Her “day job” in pathology was augmented by a collaboration with Vera Charles on a USDA Bulletin on common mushrooms. She was a vital part of the triumvirate of women mycologists at the USDA; Charles, Patterson and Cash.

According to

Another USDA mycologist was William Webster Diehl (1891–1978;

Anna Eliza Jenkins (1886–1972) was a New Yorker. Born in Walton, in 1907, she enrolled at Cornell University, where she obtained a B.S. in 1911 and an M.S. in 1912. She was hired by the USDA in 1912, without a Ph.D. and she became an Assistant Scientist in the Bureau of Plant Industry. After some additional studies in Washington DC, she received her Ph.D. from Cornell in 1927. Her professional duties dealt with diseases of imported plant material, but soon she began a series of studies of particular causal organisms. She progressed through the ranks to Mycologist in 1945 (through 1952). Her distinguished career surrounded Lange’s visit of 1931 and she was one of the several working mycologists in Washington at the time of his visit (

Another of the mycologists hired by the USDA just after the turn of the 20th century was John Albert Stevenson (1890–1979). Born in South Dakota, his early years passed in a fishing village on the shore of Lake Superior in Wisconsin (

Stevenson’s career, like that of several other young mycologists, began with some years in the Caribbean, especially Puerto Rico (

Stevenson was a collector. Professionally, his collections were of botanical specimens and professional books. As a second penchant, he was a philatelist. The latter two collections were more than significant.

Stevenson’s major contributions were archival (

Brasstown, North Carolina (21 Oct): This stop appears only on the Lange’s itinerary, but must have been sentimental, as it surely was centred in the John C. Campbell Folk-school and perhaps a reunion with Olive Dame Campbell.

New York City (surrounding 26 Oct): Contrary to its inauspicious announcement in Mycologia, Lange was sent off from his American visit at an august occasion (

Equally low key, Morten (

With their American odyssey over, what were the repercussions?

Chapter 4. Intermission

Even as the Langes toured North America in 1931, a drought had descended over an enormous territory from Colorado to Nebraska, a condition observed by

As the Langes pulled away from the American dock in fall, 1931, political jockeying was already underway for the 1932 presidential election. The Great Depression engulfed the country, and whether at fault or not, Herbert Clark Hoover (1874–1964), the President, was perceived as a non-action leader. His Republican political party shared a philosophy of a small government role, while Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945), the eventual Democratic candidate, promised a larger role of government in bringing the Depression under control and delivering aid to the people. A year later, Roosevelt won the November 1932 election (both popular and Electoral College) by a landslide, but by law, the election winner in November only took office in March of the following year, in this case, 1933. The American people had to wait for Roosevelt to act. Jakob Lange, after all, was a seasoned politician and surely was interested in the American political process. During the trip, conversations with Americans must have been animated. In Denmark, Lange’s party would side with a large and liberal role for national government and he would have appreciated the Roosevelt programme more completely than that of Hoover.

Upon arrival home, there was little time to digest the kaleidoscope of the trip. By the time the Langes left for their trip, eight instalments of the “Studies” series had appeared and already plans were afoot to publish all his water-coloured mushroom “portraits” together in a more substantial form.

Morten (

Jakob’s duties as headmaster of the Folk-school competed with mycological activity. “Specimens were collected on a morning’s walk through the wood or at one or two Sunday excursions. Each year gave some new paintings” (

It took Jakob three years to gather his thoughts into written form for English-speaking colleagues (

It is not easy to extract the core of

For Americans, it must have been a challenge to comprehend Lange’s ideas of parallelism. Whether the difference between an American mushroom and its European counterpart was 1% or 4%, distinction was distinction and at what percentage of distinction (and of what characters) did such mushrooms qualify as simply infraspecific variations: forms, varieties or subspecies? At each stop on his tour, Lange was more than willing to exhibit his illustrations, but to appreciate them, the viewer was obliged to make close observation, even to the point of using a hand-lens.

“But what about parallelism in the world of fungi? It goes without saying that the more numerous the truly Americo-European species are, the less will be the chance of meeting with parallels. Still their number seems to be not at all insignificant.

“Altogether the number of true parallels substituting European forms in the Western Hemisphere and not found on the European side of the Atlantic, seems to be rather limited. Evidence is as yet far too incomplete to draw any final conclusions with regard to the problem of parallelism. But to my mind, the facts point in a certain direction: Everywhere in the vegetable and animal kingdom new ‘small species’ or varieties seem to arise by ‘mutation’’ (sudden leaps or sidesteps from the straight path of heredity). If such new forms be equally well - or better - adapted to the natural conditions in the country where they arise, they may establish themselves there or even become the exclusive possessors of the territory hitherto occupied by the parent species. If such new forms have limited means of dispersal, they will become local species. If adapted for wide dispersal, they may gradually spread over unlimited areas.

“… in addition to the direct effect of the climatic conditions, the fungus-flora evidently is influenced by the phanerogamic vegetation, more especially by the presence or absence of certain trees [with] which the particular species is attached. This may account for a good deal of the incongruity of the floras of Europe and America and those of the eastern and western United States”.

Description of mycorrhizae had begun in the late 19th century and by 1934, the idea was well-developed, although species-to-species associations and detailed mycorrhizal anatomical studies were still 20 years ahead. Why Lange did not use the term remains obscure.

“But stronger and more lasting than any other impression is the evidence of the wonderful cosmopolitanism of the Agarics” (

Even as the Langes made their way across North America, there was an “Announcement of formation of the Mycological Society of America at the New Orleans (1931) meeting. Its first meeting will be December 28–30 (1932) in Atlantic City” (

After a career of teaching, Jakob retired from active administration of the Odense “Husmandsskole” in 1934 (Fig.

Across Europe, the 1930s had started with a conquered Germany and widespread physical and material ruin. Soon, however, disquieting words and sentiments sent signals of a new Germany (and later, Italy) echoing years of a philosophy dubbed “Lebensraum” (“living space”), introduced in the 19th century, but now championed by a rising personality, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945). The idea had two roots: the Aryan people were special (“Übermenschen”) while neighbouring people were lesser (“Untermenschen”); as the Aryan people needed additional soil through which to support themselves (Fig.

By the mid-1930s, Hitler had taken control of German government and re-armament was underway, officially “swept under the rug” by the conquering powers, themselves tired of war. Austria was gathered under the German Reich as fellow Aryans and “Lebensraum” was dusted off, openly threatening Poland and Czechoslovakia. Viewing the gathering clouds, Scandinavia, again, strived to stay, officially at least, neutral.

Meanwhile, Franklin D. Roosevelt took office as president on 4 March 1933 and immediately began implementing programmes to alleviate the economic crisis of “The Great Depression.” In June, he passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which gave workers the right to organise into collective representative organisations - in short, unions. Its most significant passage was:

“Employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and shall be free from the interference, restraint or coercion of employers”. Although the NIRA was ultimately deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935, it was immediately

replaced by the Wagner Act legislation (the National Labor Relations Act) with the same intent and workers were encouraged to join and strengthen unions and other such organisations. Expressly excluded from the union movement were agricultural workers – but the law’s overall motive was close to the heart of Jakob Lange.

The “mid-term elections” (held in the midst of the presidential term of office) of 1934 might have reflected the “radical upheaval sweeping the country,” as the Roosevelt administration won the greatest majority either party ever held in the Senate and in the House of Representatives, 322 Democrats to 103 Republicans. Coincidentally, the strength and independence of the Executive Branch was expanded as never before.

The year 1935 brought the 10th in

An unexpected reader was John

According to Morten (

The appearance of FAD was the result of clear-eyed business collaboration, not only the realisation of a mycological dream. Years previously, Lange had already had a mycological disagreement with Ferdinandsen and Winge (1924–1925), two of the chief collaborators on FAD. It concerned proposal by the latter two of a new species of Russula (R. solaris), which Lange considered only R. raoultii, already described by Quélet and already known from the Danish mycoflora. Later (Studies XII: 103, 1938a), however, Lange acknowledged the new species. The three remined friends and colleagues throughout.

Such an auspicious start was bound to be recognised by the mycological community, both European and American. In the German journal, “Annales Mycologici” (1935 [1936], 34(2): 265) both number 10 of the “Studies” series and Volume I of FAD were simply acknowledged under “neue literatur”.

In Paris, Roger

“He seeks – within the genera – to group the taxa in a logical way by using simple and clear distinctions. Mr. Lange is a master of this game and it is perhaps especially this charm from his publications which is retained and reappears in an agreeable way. ... Lange always insists on the precision of the descriptions by adding twigs, dung and other precise biological characters [to the illustrations], rarely recognized by other authors.

“All those who regretted that these essays were applied to a small number of genera will be fully satisfied when they learn that this Flora will be the generalization of the author’s previous observations, to which are added excellent watercolours in the sense that they are those that mycologists may desire; without too deliberately artistic effects, but scientifically complete and rigorous”.

As Volume 1 dealt with Amanita and Lepiota, Heim discussed these genera and their infrageneric taxonomy, noting differences between Lange’s arrangement and that of contemporary French authors.

“We sincerely hope that the real difficulties in these times [the Great Depression and the build-up to WW II] will not delay the publication of such a precise work, which simultaneously brings honour to the knowledgeable author and to two Danish groups which have taken on this enterprise”.

Virtually simultaneous with Lange’s first instalment of FAD came a mushroom book from the United States, illustrations from which rivalled those by Lange. Louis C.C. Krieger had worked with W.G. Farlow (

The year 1935 also saw a paper on American Mycena taxa by Alexander H. Smith. Smith had started his graduate work under Calvin H. Kauffman at the University of Michigan, but had to switch to E.B. Mains when Kauffman was incapacitated. Under Mains’ influence, Smith obtained his PhD in 1933, with a dissertation on two-spored forms of Mycena in North America. He had ample reference to

Now, some twenty years after Lange’s study, Smith wrote: “No comprehensive treatment of the genus Mycena giving proper emphasis to both microscopic and macroscopic characteristics has been published for the North American species. Atkinson had such a study in mind and, at the time of his death, he accumulated considerable information toward that end. Unfortunately, however, it was never published. Kauffman was engaged in a similar study in 1929, but withheld it from publication because he felt that it was incomplete. As a result, Kauffman’s treatment of the genus in ‘The Agaricaceae of Michigan’ and that of

“Very little authentic European material has been available for comparison and it has been necessary to rely on published descriptions and figures”.

An important “déviation obligatoire” is necessary. In 1922, a small paper appeared in a new journal from Germany, “Zeitschrift fur Pilzkunde” and was authored by a young Rolf Singer (1906–1994;

In February, 1936, Hitler convinced the Chancellor of Austria to allow Germany to control the Austrian economy, citing the unity of Aryan peoples. The next month, German troops marched into the Rhineland; numerous Germans saw difficult times ahead and felt obliged to emigrate from their fatherland.

January 1937 saw the 11th instalment of the “Studies” series (

“… The first volume [of FAD] appeared in 1935 and 1936. Although the author [Lange] has confined himself to the Agaricaceae of Denmark, his work is indispensable to critical students of the family in the United States and Canada. Many of the curious and unusual species which Dr. Lange has discovered are widely distributed and are to be found both in eastern North America and along the Pacific Coast. The work is outstanding because all the species recognized in the Danish flora are described and illustrated. An unusually high degree of accuracy has been obtained in depicting and reproducing the natural colours and fine details in each species. There are keys to all the species and brief descriptions which emphasize the characters the author considers important”.

Smith summarised the taxonomic outline of the two volumes. He then pointed out a few nomenclatural shortcomings. “Such errors as these are practically inevitable in a group where little authentic material exists and the literature is widely scattered. They do not detract materially from the value of the work as a whole. There is little doubt that Lange’s Agaricina Danica [sic] will always remain one of the outstanding contributions in Agaricology.”

A few months after the appearance of Smith’s review, he and Marcel Josserand (

The authors wrote: “…Lange in his comments on agarics in North America discussed briefly the existence of “parallel species” in North America and in Europe. He also re-emphasised the view, which many American mycologists have long held, that, in reality, the North American fungous flora and that of Europe are characterized by the presence of a larger number of species in common than the published floras indicate. The task of accurately determining the true synonyms and the recognition of ‘parallel species’ is a very delicate one and involves a careful study of the variations of each species not only in each country, but in various regions of the same country as well as in the same locality over a period of several seasons. The co-existence of a striking character in a European and an American species does not suffice to justify the identification of the one with the other. In order to pronounce them synonyms, it is necessary to have a perfect superposition of the two series of characters. If there is the slightest doubt, it appears to be wiser not to place them in synonymy for we believe that it is incomparably less serious and less confusing to permit the existence of two names for the same plant than to designate a mixture of two species with a single name”.

It is not surprising that Josserand & Smith should single out Mycena in their criticisms. In 1935, Smith was two years out of graduate school at University of Michigan, with his dissertation on two-spored forms in the genus in North America. Lange’s English report on his 1931 trip had appeared only in 1934 and the paper with Josserand was Smith’s first chance to comment on Lange’s remarks on biogeography of Mycena.

Time has blurred precisely how much

Lange may have stopped in Seattle or not, but his influence was felt nonetheless.

Lange’s visit with S. M. Zeller in Corvallis, listed in his itinerary and vouchered by specimens included in MycoPortal, was reflected by

A year after Volume II of FAD (

Chapter 5. 1939

Jakob’s (1938b) recollections of his American travels were written a year before his final trip to America. Fortunately, Morten’s account of the 1939 trip, although brief, is precise and accurate.

From the American side, the year opened with some equivocations on that year’s foray time and location (

From Morten

The years leading to

As early as 1922, Italy had devolved from monarchy to fascism. Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) saw his paramilitary descend on Rome and was rewarded with the prime minister’s appointment. On 3 January 1925, he asserted his right to be supreme ruler and declared himself dictator of Italy.

A decade later, following Italy’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia, Germany was the second country to recognise Italy’s legitimacy there. Over subsequent years, Germany’s industrial might and population propelled Hitler to eclipse Mussolini. Both Hitler and Mussolini sided with Francisco Franco (1892–1975) in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), with Mussolini providing 50,000 troops. In 1937, Italy left the League of Nations in solidarity with Germany. Parenthetically, 1935 saw Rolf Singer and his wife forced to flee Spain for Paris.

Perhaps a useful means of communicating the events of the period is through a chronology as follows:

12 March 1938: The Anschluss, the annexation of Austria into Greater Germany, began as a large contingent of German troops entered Austria. The Anschluss ostensibly reunited ethnically similar Aryan cultures and many Austrians welcomed the German soldiers.

March 1938: Volume III of FAD appeared in the midst of threatening times (

30 September 1938: In Munich, Germany, representatives of the victorious countries of World War I ceded to Germany the Czech Sudetenland – the Czechoslovakian borders on its west, south and north. The territory included the major defences of Czechoslovakia against Germany and Poland, so the Czechs were rendered defenceless. Soon, the remaining Czech territories and the Hungarian border land were also awarded to Germany. The British Prime Minister, Arthur Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940), upon arrival home after the Munich Conference, declared its agreements as “Peace for our time”.

In the context of the post-war (WW I) economic depression of the 1930s, the German National Socialist Party (“Nazi”) gained popularity in part by presenting Jews as the source of a variety of political, social, economic and ethical problems permeating German society. The Nazis used racist and also medieval social, economic and religious imagery to this end. Inspired by theories of racial struggle, Hitler preached the intent of the Jews to survive and expand at the expense of Germans. The Nazis, as the governing party, ordered anti-Jewish boycotts, staged book burnings and enacted anti-Jewish legislation. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws defined Jews by race and mandated the total separation of “Aryans” and “non-Aryans”. These measures aimed at both legal and social segregation of Jews from Germans and Austrians. On the night of 9 November 1938, Nazis and their sympathisers destroyed synagogues and shop windows of Jewish-owned stores throughout Germany and Austria in what became known as “Kristallnacht”.

Simultaneously, people of German ancestry living abroad were encouraged to form citizens groups both to extol “Germanic virtues” around the world, but also to lobby for causes helpful to Nazi Party goals (

October 1938: The 12th and final instalment of

March 1939: German army occupied Prague, Czechoslovakia, in clear violation of the Munich Agreement.

31 March 1939: In the face of the perceived German threat, Britain and Poland announced a mutual assistance pact in case of military threat, but the treaty was not signed until August. From the British Prime Minister: “... [I]n the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence and which the Polish Government accordingly considered it vital to resist with their national forces, His Majesty’s Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Polish Government all support in their power. They have given the Polish Government an assurance to this effect. I may add that the French Government have authorised me to make it plain that they stand in the same position in this matter as do His Majesty’s Government”. On 13 April, the assurance was extended to Greece and Romania. Formal signing was accomplished on 25 August.

May 1939: Germany demanded a non-aggression pact with the Scandinavian countries. Sweden and Norway rejected the idea, but Denmark accepted, which created a major physical obstacle for the Britain/Poland alliance.

Early May 1939, Volume IV of FAD appeared in Denmark (

22 May 1939: Italy and Germany signed the “Pact of Steel” officially creating the Axis powers. (Japan would join in September of 1940 with the signing of the “Tripartite Pact”).

12 August1939: The Langes, father and son, pushed off from England for New York “on a fast boat,” arriving on 18 August and immediately boarded a train headed south towards Tennessee and a “mycological congress.” Morten was impressed that they disembarked at 6:30 pm Daylight Savings time and boarded the train at 6:30 pm Standard time. Daylight Savings Time had been instituted during World War I, but afterwards had been scrapped. Roosevelt attempted to resurrect it, but it was rejected again, except for a very few States and large cities, one of which was New York. The railroads ran on Standard Time and this would persist all the way to Tennessee.

It must have been no sooner than 19 August that the Langes reached Gatlinburg, Tennessee and the 1939 foray of the Mycological Society of America. The foray was scheduled for 17 – 20 August, so the Langes had no more than a few hours with the large contingent of mycologists – just long enough to be caught in a group photo (Fig.

Mycological Society of America Foray, 1939, Gatlinburg, TN 1 Helen Smith 2 David Linder 3 L.R. Hesler 4 Robert Hagelstein 5 Arthur Stupka, Smokey Mountains National Park biologist 6 Alexander H. Smith 7 L.O. Overholts 8 Morten Lange 9 John Dearness 10 C.L. Shear 11 J.E. Lange. Source: L.R. Hesler.

It is quite possible that a small group of mycologists remained in Gatlinburg for extra collecting and conversation. A second photo might suggest that amongst them were C.L. Shear, John Dearness and Robert Hagelstein (Fig.

23 August 1939: Meanwhile, secretly, the USSR was negotiating with both Britain and Germany. The deal with Germany promised a Soviet “Sphere of Influence” including eastern Europe, the Baltic States and Finland. Joseph Stalin was attracted to this much better deal from Hitler and the USSR signed the (Vyacheslav) Molotov-(Joachim von) Ribbentrop Pact.

Morten (

25 August (probably): Morten wrote (

In 1931, the Lange family had visited Washington, where they spent time in the field with USDA workers. Most of those folks were still in their jobs and reunions were probably pleasant. At least Cornelius Shear and Vera Charles had been at the Gatlinburg foray, lending additional familiarity.

Morten described the lectures as agricultural, not mycological and used the plural, but nothing specific is known about them. One person already known to Jakob was Henry Agard Wallace (1888–1965), then Secretary of Agriculture under Roosevelt and slated to be Roosevelt’s Vice President after the 1940 election.

Sounding much as though it could have come from Grundtvig’s pen, “The Farmers’ High School” was established in Pennsylvania in 1855, seven years before the land-grant act was passed. The implication, of course, was that agriculture already played a significant role in the mission of the school, reflecting the rural agrarian demographics. The first graduating class of 13 males in 1861 was the first such class at an American agriculture institution. Just as the Grundtvigian schools in Denmark, agricultural programmes at “Penn. State” included numerous short courses so students could receive education and immediately apply their new knowledge to their livelihood.

In terms of mycology, at least three faculty members were on board in 1939. Frank Dunn Kern (1883–1973), expert in rust fungi, was not only Head of the Department of Botany, but also Dean of the Graduate School. George Lorenzo Ingram Zundel (1885–1950) was plant pathology’s extension representative to the farming public. Lee Oras Overholts (1890–1946) had already published several papers on polypores and had served as President of the Mycological Society of America in 1938. He had just attended the Gatlinburg foray the previous month. James Whaples Sinden (1902–1994) was becoming well-known for his development of “grain Spawn” in the mushroom industry.

In the 19th century, caves in and around Chester County, Pennsylvania, had become home for a thriving mushroom growing industry, businesses often owned and run by immigrant families. With the advent of mechanical aids, especially in ventilation, the industry went above ground and, after World War II, the area produced the lion’s share of mushrooms in the United States. Pennsylvania State University evolved an advisory role to the mushroom farmers’ association, later adding a research laboratory and short courses of its own to serve as extension, under the leadership of Leon R. Kneebone (1920–2020;

1 September 1939:

On that very day, Hitler, convinced that Britain would not intervene and assured that USSR would not interfere, sent troops into Poland in the face of the Munich Conference agreement and the mutual assurance pact between Poland and Britain. Within days, the USSR entered Poland from the east and the country essentially disappeared.

Great Britain immediately declared war against Germany. This was not a singular event, for British agreements with its dominions – Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and other colonies such as India and African possessions – brought them also into the War, both in Europe and across the Pacific.

September 1939: Denmark’s reaction to these tumultuous events was to declare neutrality, as it had been for World War I. Danish government and society continued to function more or less normally, but always “looking over their shoulders” as their southern neighbours killed one another. The southern areas of Schleswig and Holstein were again in play. The Germans, contrary to their other incursions, considered the Danes a kind of Aryan and therefore qualified for less harsh treatment.

A stop in New York City would not have been complete without a visit to Columbia University to see John Sidney Karling (1887–1994;

The evident reason for the change in transatlantic schedule were widely circulating reports of German “U-boats” (submarines) plaguing shipping on Atlantic seaways. On the advice of American hosts and colleagues, bookings were changed to the “Gripsholm,” a vessel of the Swedish-American Line, which sailed under the flag of neutral Sweden. Morten (

20 September 1939: The Lange men arrived home. With this, the 1939 North American visit ended, but the tension and stress of the return voyage was only enhanced by the turmoil on all sides of Denmark. Nevertheless, it must have been welcome to return to retirement at the Odense “Husmandsskole”.

Chapter 6. Epilogue

17 December 1939: As the year wound down, in Berlin, the decision was made to occupy Denmark. Within days, German troops occupied Copenhagen, violating Denmark’s neutrality. The Germans had already planned to use northernmost Denmark as a jumping off spot in an invasion of Norway.

Morning, 9 April 1940: Germany declared Denmark a protectorate as it began the invasion of Norway. Norwegian resistance was valiant, but failed and Norway capitulated on 10 June. With Denmark and Norway in its pocket, Germany controlled commerce over the Baltic Sea.

9 April 1940: The Danish envoy to the US signed an agreement under which the US would defend Greenland, a Danish protectorate. The agreement also provided the US an opportunity to erect military bases on the Island. This arrangement moved the US closer to the war without being directly involved.

12 April 1940: With Danish permission, Britain peacefully invaded the Faroe Islands, another Danish protectorate and fortified them.

10 May 1940: The United Kingdom invaded Iceland as a pre-emptive strike, eventually turning it over to the USA in July 1941. Occupation of the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland were all attempts to preserve the northern transatlantic waterway.

Germany’s occupation of Denmark and invasion of Norway convinced Mussolini that Hitler would win the war. In continental Europe, neutral Holland (15 May 1940) and Belgium (28 May 1940) also fell to the Germans.

26 May – 4 June 1940: The German army advanced over its western front, trapping large numbers of British and French troops against the British Channel, necessitating their evacuation from Dunkirk.

June 1940: The French military collapsed and occupation began over much of the country.

In mid-September, 1940, Volume V of FAD appeared (Figs

22 June 1941: Under “Operation Barbarossa,” Germany started its invasion of the USSR, ripping asunder the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

It was surely Germany’s most grievous over-extension and the beginning of the end for Axis powers (Germany and Italy).

On the very same day, German occupation authorities in Denmark demanded that Danish communists be arrested. The Danish government complied and, in the following days, the Danish police arrested over 300 communists. Many of these, including the three communist members of the Danish Parliament, were imprisoned, in violation of the Danish constitution. On 22 August, the Danish Parliament (without its communist members) passed the “Communist Law”, outlawing the Communist Party and communist activities, in another violation of the Danish constitution. In 1943, about half of the detainees were transferred to Stutthof (