Today’s media, whether it be traditional or social, is full of hot takes, sensationalism, and massive amounts of hyperbole. I often wonder how different things would be if we had internet and social media back in the 1800s, but then I snap out of it and realize that we probably haven’t changed all that much, things were just slower back then. Today, we can pass around and debunk Betty White’s death and reincarnation as an android in the span of 24 hours. In the 1800s it might have taken decades to prove she was alive and kicking, capturing the imagination of generations in the meantime. This is probably how urban legends and folklore gained traction, and the myths of the upas tree are a great example.

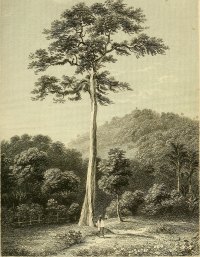

The upas tree, Antiaris toxicaria, grows throughout the world, particularly the tropical areas of Africa, Asia, and Australia. It is a massive, stately tree that can reach heights of 120 feet (40 meters) and in the 1800s known as a matter of fact to be “one of the most deadly vegetable products of creation (1, check out this book title).” While this very well could have been true at the time, the other legends of the deadly upas tree are harder to believe. It was said that the tree lived in plains devoid of all other vegetation and that no living creature could live within three leagues (ten miles) of it due to its noxious, poisonous vapors that left the ground littered with the skeletal remains of man and creature alike. This has all the makings of a Stephen King novel. I guess no one thought to ask “if you can’t get within miles of it, how do you know it even exists?”

The famed upas tree was so well known that it was a common metaphor for anything poisonous or toxic and used many times in political cartoons of the 1800s. It was definitely a part of society and understood by all. Even Erasmus Darwin, the famed philosopher poet and grandfather of Charles, got in on the action. He wrote of the famed tree in his poem The Loves of the Plants:

Fierce in dread silence on the blasted heath,

Fell upas alts, the Hydra-Tree of death.

All of these descriptions of the upas tree are too extreme to be believed, of course, and proven untrue in 1810 when French botanist Jean-Baptiste Leschenault explored the Indonesian island of Java. He quite literally found himself in a thick forest, face-to-face with an upas tree…and lived to tell the tale! Not convinced to merely gaze upon its poisonous splendor, he cut it down. He even accidentally smeared the latex, oozing from the cut wood, onto his hands, without any ill effects. He was absolutely certain, however, that if he had cuts on his hands, the sap surely would have ended his life. To prove the point he injected a drop of the Javan upas juice into a dog, which died within five minutes. It took 8 drops to kill a horse in the same amount of time. Why he felt the need to kill a dog and a horse is beyond me.

The legend of the upas tree isn’t all steeped in hyperbole, though. The milky latex from Antiaris toxicaria was used as an arrow poison for long periods of time. The liquid was collected from cut trees and dried, concentrating the poison, before being applied to the tips of arrows and darts. In Malaysia this method was used in hunting small game, such as monkeys and birds, and also larger animals, like deer and boar. It was the poison, spread on the tips and shafts of darts that killed their prey, not the darts themselves.

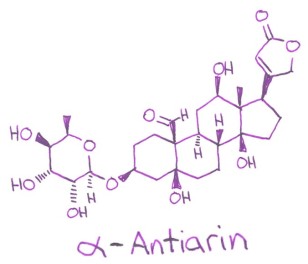

Today, two collections of Malaysian dart poisons originally obtained in 1883 and 1924 were analyzed (2). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was used to isolate and identify the components of the poisons. Analysis revealed the cardiac glycoside antiarin, along with several other related steroids, in each of the poison samples. The experiments also found strychnine in several of the samples, which is not so surprising given that arrow and dart poisons are typically a “witches brew” of plant and animal toxins.

Antiarin is a cardiac glycoside, much like digoxin, oleandrin, and cerberin, which we’ve encountered a few times on this blog. Like the others, it has a steroid backbone, specifically a cardenolide, conjugated with a sugar moiety (the “glycoside” part). Like the aforementioned glycosides, antiarin also has potential medical use as a treatment for heart failure. Its use as an arrow and dart poison, however, is much more interesting, as it has a reported LD50 (the concentration needed to kill 50% of the tested population) of 0.11 mg/kg in mammals, making it more lethal than the famous curare (0.5 mg/kg) (3). The key to dart poisons is that poisoned meat must be safe to eat, and that is certainly the case with antiarin. When cooked, the glycoside on antiarin hydrolyzes (pops off), rendering the poison inactive and the meat safe to consume.

Antiarin is a cardiac glycoside, much like digoxin, oleandrin, and cerberin, which we’ve encountered a few times on this blog. Like the others, it has a steroid backbone, specifically a cardenolide, conjugated with a sugar moiety (the “glycoside” part). Like the aforementioned glycosides, antiarin also has potential medical use as a treatment for heart failure. Its use as an arrow and dart poison, however, is much more interesting, as it has a reported LD50 (the concentration needed to kill 50% of the tested population) of 0.11 mg/kg in mammals, making it more lethal than the famous curare (0.5 mg/kg) (3). The key to dart poisons is that poisoned meat must be safe to eat, and that is certainly the case with antiarin. When cooked, the glycoside on antiarin hydrolyzes (pops off), rendering the poison inactive and the meat safe to consume.

We gain energy from the foods we consume, but we are in fact, electric. The flow of charged ions throughout our body causes our muscles to contract and our hearts to beat. It is a wondrous operation, but just like a movie villain ripping cables out of an electrical panel, sending sparks flying and lights shuttering, our electric machinery can go haywire, too. The sodium-potassium pump, located throughout the body, is a transport protein that, true to its name, pumps sodium out of the cell and potassium into it. The net effect is a voltage difference between the inside and outside of the cell, what we call a membrane potential. When the potential, or charge, rises and falls along the membrane, signals are sent, much akin to electricity flowing down a wire to illuminate a lightbulb or power a motor. This is how biceps contract, hearts beat, and neurons in the brain fire – the flow of charged ions into and out of the cell. A dichotomy between a simple concept and complex biomachinery.

Cardiac glycosides inhibit sodium-potassium pumps. In an overdose, antiarin is the movie villain. Sparks are flying and machinery is shutting down. Our heart rate slows and our muscles are weakened. Other effects come from alterations of our sympathetic nervous system – also controlled by electrical impulses – and include blurred vision and the winning trifecta of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Without supportive care, and an expensive antidote called Digibind, you’ll probably die.

So while the upas tree doesn’t kill wildlife within a 10-mile radius, and the trunks aren’t surrounded by the skeletal remains of its victims, the antiarin it contains is a potent toxin with a well-established history as a dart poison. The myths and legends of such things are interesting to read about today, and no doubt would have been readily debunked had social media existed back then, but I’m glad we have them as a reminder of how far we’ve come, if not for the entertainment value. Now, Alexander Hamilton on Twitter? I’d sign up for that!

References:

- Buel, James W. Sea and Land: an Illustrated History of the Wonderful and Curious Things of Nature Existing before and since the Deluge …: Being a Natural History of the Sea Illustrated by Stirring Adventures with Whales …: Also a Natural History of Land-Creatures Such as Lions …: to Which Is Appended a Description of the Cannibals and Wild Races of the World, Their Customs, Habits, Ferocity and Curious Ways. J.S. Robertson, 1887.

- Kopp, B., et al. “Analysis of Some Malaysian Dart Poisons.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 36 (1992): 57-62.

- Zhou, Jiaju, Guirong Xie, and Xinjian Yan. Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicines. Berlin: Springer, 2011.

* Featured image of The Deadly Upas Tree of Wall Street by Joseph Keppler, 1882 (CC 0) *

Thankyou so much for the marvellous explanation of the electric body, I never properly understood this before, finally I get it!

Thanks so much!

Interesting, and good to know about yet another cardiotoxic glycoside that’s out there. We work with a variety of these in our lab but this is one I hadn’t run across.

Actually there’s a major city in Malaysia – Ipoh – named after the upas tree. The standardised spelling in modern Malay is ipuh. We know it’s toxic but I thought it was hilarious when I found out about its wildly exaggerated reputation in western literature.

Link to the national Institute of Language and Literature’s dictionary search page: http://prpm.dbp.gov.my/cari1?keyword=ipuh

Another mention of ipuh trees in western literature is Pushkin’s The Upas Tree https://www.poemhunter.com/best-poems/alexander-sergeyevich-pushkin/the-upas-tree/

Out of topic, but apparently mushroom poisonings are on the rise in Australia thanks to a bumper crop this year.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/may/13/mushroom-foragers-warned-amid-jump-in-poisonings-in-australia

This reminds me of the Australian giant eucalyptus, aka the Widowmaker. Not poisonous, but does tend to survive droughts by spontaneously self-pruning heavy branches onto unsuspecting campers sleeping below. “Go big or go home” – that would be my motto if I was an Australian tree.

My god. Betty White is a robot now? Is this true? I gotta go tell reddit.

Pingback: Weeping—no, Eating?—Willow | doubtfulsea

Hello, do you know how long the poison is stable? Would a poison dart be the same poisoness after 40 years?

Best wishes