Posts Tagged ‘Poison Ivy Berries’

Things I’ve Seen

Posted in Nature, Things I've Seen, tagged Canon EOS Rebel T6, Coneflower Seedhead, Crab Apples, Gray Squirrel, Half Moon Pond, Hancock New Hampshire, Horse Nettle Fruit, Ice Storm, Icy Branches, Keene, Monkshood Seed Pods, Native Plants, Nature, New Hampshire, NH, Olympus Stylus TG-870, Poison Ivy, Poison Ivy Berries, pond ice, Puddle Ice, Rose of Sharon Seed Pod, Snow Ripples, Stress Cracks in Ice, Swanzey New Hampshire, Winter Hiking, Winter Plants, Winter Woods on January 11, 2020| 21 Comments »

Things I’ve Seen

Posted in Nature, Things I've Seen, tagged Beaver Dam, Blue Crust Fungus, Canon EOS Rebel T6, Cinnamon Fairy Stool Mushroom, False Solomon's Seal Fruit, Fly Agaric Mushroom, Golden Pholiota Mushroom, Hen of the Woods, Jack in the Pulpit Berries, Keene, Kousa Dogwood Fruit, Mountain Ash Fruit, Mushrooms, Native Plants, Nature, New Hampshire, NH, Olympus Stylus TG-870, Painted Lady Butterfly, Poison Ivy Berries, Sleeping Bee, Spreading Yellow Tooth Slime Mold, Stinkhorn Mushroom, Swanzey New Hampshire, Virginia Carpenter Bee, Wild Mushrooms, Wooly Bear Caterpillar, Yew Berry on October 16, 2019| 30 Comments »

We’re still very dry here and I haven’t seen hardly any of the mushrooms I’d expect to see but here was a dead birch tree full of golden pholiota mushrooms (Pholiota limonella) just like it was last year. I thought that’s what they were until I smelled them but these examples had no citrus scent, so I’d say they must be Pholiota aurivella which, except for its smaller spores and the lack of a lemon scent, appears identical.

The frustrating thing about mushroom identification is how for most of them you can never be sure without a microscope, and that’s why I never eat them. There are some that don’t have many lookalikes and though I’m usually fairly confident of a good identification for them I still don’t eat them. It’s just too risky.

One of my favorite fungal finds is called the tiger’s eye mushroom (Coltricia perennis.) One reason it’s unusual is because it’s one of the only polypores with a central stem. Most polypores are bracket or shelf fungi. The concentric rings of color are also unusual and sometimes make it look like a turkey tail fungus with a stem. The cap is very thin and flat like a table, and another name for it is the fairy stool. They are very tough and leathery and can persist for quite a long time.

I found it this hen of the woods fungus (Grifola frondosa,) growing at the base of an old oak tree. This edible polypore often grows in the same spot year after year and that makes it quite easy to find. They are said to look like the back of a brown hen’s ruffled feathers, and that’s how they come by their common name. Though they’re said to be brown I see green.

I saw a young fly agaric (Amanita muscaria v. formosa) in a lawn recently. I love the metallic yellow color of these mushrooms when they’re young. They’re common where pine trees grow and this one was under a pine. The name fly agaric comes from the practice of putting pieces of the mushroom in a dish of milk. The story says that when flies drank the milk they died, but it’s something I’ve never tried. Fly agaric is said to have the ability to “turn off” fear in humans and is considered toxic. Vikings are said to have used it for that very reason.

I don’t see many stinkhorn fungi but I hit the stinkhorn jackpot this year; there must have been 20 or more of them growing out of some well rotted wood chips. I think they’re the common stinkhorn (Phallus impudicus) and I have to say that for the first time I smelled odor like rotting meat coming from them because these example were passing on.

Here was a fresher example. The green conical cap is also said to be slimy but it didn’t look it. This mushroom uses its carrion like odor to attracts insects, which are said to disperse its sticky spores. I saw quite a few small gnat like insects around the dying ones.

At this time of year I always roll logs over hoping to find the beautiful but rare cobalt crust fungus (Terana caerulea,) but usually I find this lighter shade of blue instead. I think it is Byssocorticium atrovirens. Apparently its common name is simply blue crust fungus. Crust fungi are called resupinate fungi and have flat, crust like fruiting bodies which usually appear on the undersides of fallen branches and logs. Resupinate means upside down, and that’s what many crust fungi appear to be. Their spore bearing surface can be wrinkled, smooth, warty, toothed, or porous and though they appear on the undersides of logs the main body of the fungus is in the wood, slowly decomposing it. They seem to be the least understood of all the fungi.

Some slime molds can be very small and others quite large. This one in its plasmodium stage was wasn’t very big at all, probably due to the dryness. When slime molds are in this state they are usually moving-very slowly. Slime molds are very sensitive to drying out so they usually move at night, but they can be found on cloudy, humid days as well. I think this one might be spreading yellow tooth slime (Phanerochaete chrysorhiza.) Slime molds, even though sometimes covering a large area, are actually made up of hundreds or thousands of single entities. These entities move through the forest looking for food or a suitable place to fruit and eventually come together in a mass.

Jack in the pulpit berries (Arisaema triphyllum) are ripe and red, waiting for a deer to come along and eat them. Deer must love them because they usually disappear almost as soon as they turn red. All parts of the Jack in the pulpit plant contain calcium oxalate crystals that cause painful irritation of the mouth and throat if eaten, but Native Americans knew how to cook the fleshy roots to remove any danger. They used them as a vegetable, and that’s why another name for the plant is “Indian turnip.”

False Solomon’s seal (Smilacina racemosa) berries are fully ripe and are now bright red instead of speckled. Native American’s used all parts of this plant including its roots, which contain lye and must be boiled and rinsed several times before they can be used. Birds, mice, grouse, and other forest critters eat the ripe berries that grow at the end of the drooping stem. They are said to taste like molasses and another common name for the plant is treacle berry.

American mountain ash (Sorbus americana) is a native tree but you’re more likely to find them growing naturally north of this part of the state. I do see them in the wild, but rarely. Their red orange fruit in fall and white flowers in spring have made them a gardener’s favorite and that’s where you’ll see most of them here though they prefer cool, humid air like that found in the 3000 foot elevation range. The berries are said to be low in fat and very acidic, so birds leave them for last. For some reason early settlers thought the tree would keep witches away so they called it witch wood. Native Americans used both the bark and berries medicinally. The Ojibwe tribe made both bows and arrows from its wood, which is unusual. Usually they used wood from different species, or wood from both shrubs and trees.

Kousa dogwood fruit looks a little different but it’s the edible part of a Kousa Dogwood (Cornus kousa.) This dogwood is on the small side and is native to Asia. I don’t see it too often. It is also called Japanese or Korean Dogwood. Kousa Dogwood fruit is made up of 20-40 fleshy carpels. In botany one definition of a carpel is a dry fruit that splits open, into seed-bearing sections. Kousa dogwood fruits are said by some to taste like papaya.

In my own experience I find it best to leave plants with white berries alone because they are usually poisonous, and no native plant illustrates this better than poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans.) Though many birds can eat its berries without suffering, when most humans so much as brush against the plant they can itch for weeks afterward, and those who are particularly sensitive could end up in the hospital. I had a friend who had to be hospitalized when his eyes became swollen shut because of it. Eating any part of the plant or even breathing the smoke when it is burned can be very dangerous.

All parts of the yew tree (Taxus) are poisonous except (it is said) the red flesh of the berry, which is actually a modified seed cone. The seed within the seed cone is the most toxic part of the plant and eating as few as 3 of them can cause death in just a few hours. In February of 2014 a man named Ben Hines died in Brockdish, Norfolk, England after ingesting parts of yew trees. Nobody has ever been able to figure out why he did such a thing but the incident illustrated how extremely toxic yews are.

Beavers are trying to make a pond in a river and they had dammed it up from bank to bank. It wasn’t the biggest beaver dam I’ve seen but it was quite big. The largest beaver dam ever found is in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park and spans about 2,800 feet. It has taken several generations of beavers since 1970 to build and it can be seen from space. Imagine how much water it is holding back!

Eastern or Virginia carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica) are huge; at least as big as half my thumb. They also look very different than the bumblebees that I’m used to. These bees nest in wood and eat pollen and nectar. They don’t eat wood but they will excavate tunnels through rotten wood. The adults nest through winter and emerge in spring. Though it is said to be common in the eastern part of the country I I see very few. I’ve read that they can be up to an inch long and this one was all of that. Females can sting but they do so only when bothered. Males don’t have a stinger.

Folklore says that the wider the orangey brown band on a wooly bear caterpillar is, the milder the winter will be. If we’re to believe it then this winter will not be very mild because this wooly bear has more black than brown on it. In any event this caterpillar won’t care, because it produces its own antifreeze and can freeze solid in winter. Once the temperatures rise into the 40s F in spring it thaws out and begins feeding on dandelion and other early spring greens. Eventually it will spin a cocoon and emerge as a beautiful tiger moth. From that point on it has only two weeks to live.

The upper surface of a painted lady’s wings look very different than the stained glass look of the undersides but unfortunately I can’t show that to you because the photos didn’t come out. This painted lady was kind enough to land just in front of me on a zinnia. It’s the only one I’ve seen this year.

There is little that is more appropriate than a bee sleeping on a flower, in my opinion. Here in southwestern New Hampshire we don’t see many wildflowers in October, but every now and then you can find a stray something or other still hanging on. The bumblebee I saw on this aster early one morning was moving but very slowly, and looked more like it was hanging on to the flower head rather than harvesting pollen. Bumblebees I’ve heard, sleep on flowers, so maybe it was just napping. I suppose if it has to die in winter like bumblebees do, a flower is the perfect place to do that as well. Only queen bumblebees hibernate through winter; the rest of the colony dies. In spring the queen will make a new nest and actually sit on the eggs she lays to keep them warm, just like birds do.

It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see. ~Henry David Thoreau

Thanks for coming by.

Things I’ve Seen

Posted in Nature, Things I've Seen, tagged Alder Tongue Gall, Ashuelot River, bumblebee, Canon SX40 HS, Clouded Sulfur Butterfly, Comb Tooth Fungus, Cranberry, Elderberries, Great Blue Heron, Gypsy Moth Egg Case, Keene, Little Bluestem Grass, Long Horned Grasshopper, Mallards, Monarch Butterfly, Native Plants, Nature, New Hampshire, NH, Olympus Stylus TG-870, Painted Lady Butterfly, Painted Turtle, Poison Ivy Berries, Russel's Bolete, Scaly Pholiota Mushroom, Summer Wildflowers, Wooly Bear Caterpillar, Yellow Fuzz Cone Slime Mold, Yellow Tipped Coral Fungus on November 1, 2017| 30 Comments »

I’m not seeing many now, possibly because the nights are getting cooler, but I was seeing at least one monarch butterfly each day for quite a while. That might not seem like many but I haven’t seen any over the last couple of years so seeing them every day was a very noticeable and welcome change.

For the newcomers to this blog; these “things I’ve seen posts” contain photos of things I’ve seen which, for one reason or another, didn’t fit into other posts. They are usually recent photos but sometimes they might have been taken a few weeks ago, like the butterflies in this post. In any event they, like any other post seen here, are simply a record of what nature has been up to in this part of the world.

After a rest the knapweeds started blooming again and clouded sulfur butterflies (I think) were all over them. I’ve seen a lot of them this year. They always seem to come later in summer and into fall and I still see them on warm days.

This clouded sulfur had a white friend that I haven’t been able to identify. I think this is only the second time I’ve had 2 butterflies pose for the same photo.

I saw lots of painted ladies on zinnias this year; enough so I think I might plant some next year. I like the beautiful stained glass look of the undersides of its wings.

The upper surface of a painted lady’s wings look very different. This one was kind enough to land just in front of me in the gravel of a trail that I was following.

A great blue heron stood motionless on a rock in a pond, presumably stunned by the beauty that surrounded it. It was one of those that likes to pretend it’s a statue, so I didn’t wait around for what would probably be the very slow unfolding of the next part of the story.

Three painted turtles all wanted the same spot at the top of a log in the river. They seem to like this log, because every time I walk by it there are turtles on it.

Three ducks dozed and didn’t seem to care who was where on their log in the river.

Ducks and turtles weren’t the only things on logs. Scaly pholiota mushrooms (Pholiota squarrosa) covered a large part of this one. This mushroom is common and looks like the edible honey mushroom at times, but it is not edible and is considered poisonous. They are said to smell like lemon, garlic, radish, onion or skunk, but I keep forgetting to smell them. They are said to taste like radishes by those unfortunate few who have tasted them.

There are so many coral mushrooms that look alike they can be hard to identify, but I think this one might have been yellow tipped coral (Ramaria formosa.) Though you can’t see them in this photo its stems are quite thick and stout and always remind me of broccoli. Some of these corals get quite big and they often form colonies. This one was about as big as a cantaloupe and grew in a colony of about 8-10 examples, growing in a large circle.

Comb tooth fungus (Hericium ramosum) grows on well-rotted logs of deciduous trees like maple, beech, birch and oak. It is on the large side; this example was about as big as a baseball, and its pretty toothed branches spill downward like a fungal waterfall. It is said to be the most common and widespread species of Hericium in North America, but I think this example is probably only the third one I’ve seen in over 50 years of looking at mushrooms.

Something I see quite a lot of in late summer is the bolete called Russell’s bolete (Boletellus russellii.) Though the top of the cap isn’t seen in this shot it was scaly and cracked, and that helps tell it from look alikes like the shaggy stalked bolete (Boletellus betula) and Frost’s bolete (Boletus frostii.) All three have webbed stalks like that seen above, but their caps are very different.

Sometimes you can be seeing a fungus and not even realize it. Or in this case, the results of a fungus. The fungus called Taphrina alni attacks female cone-like alder (Alnus incana) catkins (Strobiles) and chemically deforms part of the ovarian tissues, causing long tongue like galls known as languets to form. These galls will persist until the strobiles fall from the plant; even heavy rain and strong winds won’t remove them. Though I haven’t been able to find information on its reproduction I’m guessing that the fungal spores are produces on these long growths so the wind can easily take them to other plants.

Elderberries (Sambucus canadensis) are having a great year. I don’t think I’ve ever seen as many berries (drupes) as we have this year. The berries are edible but other parts of the plant contain calcium oxalate and are toxic. Native Americans dried them for winter use and soaked the berry stems in water to make a black dye that they used on their baskets.

Native cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) are also having a good year. The Pilgrims named this fruit “crane berry” because they thought the flowers looked like Sandhill cranes. Native Americans used the berries as both food and medicine, and even made a dye from them. They taught the early settlers how to use the berries and I’m guessing that they probably saved more than a few lives doing so. Cranberries are said to be one of only three fruits native to North America; the other two being blueberries and Concord grapes, but I say what about the elderberries we just saw and what about crab apples? There are also many others, so I think whoever said that must not have thought it through.

In my own experience I find it best to leave plants with white berries alone because they are usually poisonous, and no native plant illustrates this better than poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans.) Though many birds can eat its berries without suffering, when most humans so much as brush against the plant they can itch for weeks afterward, and those who are particularly sensitive could end up in the hospital. I had a friend who had to be hospitalized when his eyes became swollen shut because of it. Eating any part of the plant or even breathing the smoke when it is burned can be very dangerous.

Native bluestem grass (Schizachyrium scoparium) catches the light and glows in luminous ribbons along the roadsides. This is a common grass that grows in every U.S. state except Nevada and Washington, but is so uncommonly beautiful that it is grown in gardens. After a frost it takes on a reddish purple hue, making it even more beautiful.

It is the way its seed heads reflect the light that makes little bluestem grass glow like it does.

I think the above photo is of the yellow fuzz cone slime mold (Hemitrichia clavata.) The most unusual thing about this slime mold is how it appears when the weather turns colder in the fall. Most other slime molds I see grow during warm, wet, humid summers but I’ve seen this one even in winter. Though it looks like it was growing on grass I think there must have been an unseen root or stump just under the soil surface, because this one likes rotten wood. It starts life as tiny yellow to orange spheres (sporangia) that finally open into little cups full of yellowish hair like threads on which the spores are produced.

I was looking at lichens one day when I came upon this grasshopper. The lichens were on a fence rail and so was the grasshopper, laying eggs in a crack in the rail. This is the second time I’ve seen a grasshopper laying eggs in a crack in wood so I had to look it up and see what it was all about. It turns out that only long horned grasshoppers lay eggs in wood. Short horned grasshoppers dig a hole and lay them in soil. They lay between 15 and 150 eggs, each one no bigger than a grain of rice. The nymphs will hatch in spring and live for less than a year.

The gypsy moth egg cases I’ve seen have been smooth and hard, but this example was soft and fuzzy so I had to look online at gypsy moth egg case examples. From what I’ve seen online this looks like one. European gypsy moths were first brought to the U.S. in 1869 from Europe to start a silkworm business but they escaped and have been in the wild ever since. In the 1970s and 80s gypsy moth outbreaks caused many millions of dollars of damage across the northeast by defoliating and killing huge swaths of forest. I remember seeing, in just about every yard, black stripes of tar painted around tree trunks or silvery strips of aluminum foil wrapped around trunks. The theory was that when the caterpillars crawled up the trunk of a tree to feed they would either get stuck in the tar or slip on the aluminum foil and fall back to the ground. Today, decades later, you can still see the black stripes of tar around some trees. Another gypsy moth population explosion happened in Massachusetts last year and that’s why foresters say that gypsy moth egg cases should be destroyed whenever they’re found. I didn’t destroy this one because at the time I wasn’t positive that it was a gypsy moth egg case. If you look closely at the top of it you can see the tiny spherical, silvery eggs. I think a bird had been at it.

Folklore says that the wider the orangey brown band on a wooly bear caterpillar is, the milder the winter will be. If we’re to believe it then this winter will be very mild indeed, because this wooly bear has more brown on it than I’ve ever seen. In any event this caterpillar won’t care, because it produces its own antifreeze and can freeze solid in winter. Once the temperatures rise into the 40s F in spring it thaws out and begins feeding on dandelion and other early spring greens. Eventually it will spin a cocoon and emerge as a beautiful tiger moth. From that point on it has only two weeks to live.

This bumblebee hugged a goldenrod flower head tightly one chilly afternoon. I thought it had died there but as I watched it moved its front leg very slowly. Bumblebees sleep and even die on flowers and they are often seen at this time of year doing just what this one was doing. I suppose if they have to die in winter like they do, a flower is the perfect place to do so. Only queen bumblebees hibernate through winter; the rest of the colony dies. In spring the queen will make a new nest and actually sit on the eggs she lays to keep them warm, just like birds do.

I’ll end this post the way I started it, with a monarch butterfly. I do hope they’re making a comeback but there is still plenty we can do to help make that happen. Planting zinnias might be a good place to start. At least, even if the monarchs didn’t come, we’d still have some beautiful flowers to admire all summer.

I meant to do my work today, but a brown bird sang in the apple tree, and a butterfly flitted across the field, and all the leaves were calling. ~Richard le Gallienn

Thanks for coming by.

A Rail Trail Hike

Posted in General gardening, tagged Amber Jelly Fungus, Ashuelot River, Boston and Maine Railroad, Cheshire Railroad, Frost Crystals, Keene, Little Bluestem Grass, Lowbush Blueberry, Maple Dust Lichen, Milk White Toothed Polypore, Native Plants, New Hampshire, NH, Oak Marble Gall, Panasonic Lumix DMC-527, Poison Ivy Berries, Swanzey New Hampshire, Sweet Fern, Tell Tales, White Pine, Winter Hiking, Winter Plants, Winter Woods on February 10, 2016| 43 Comments »

The plan was to get out early last Saturday and hike a rail trail since I skipped it last week in favor of a pond, but nature had other plans. We got about 5 inches of snow on Friday and the temperature at 7:00 am on Saturday was barely 17 degrees F. I thought I’d wait for the sun to warm it up a bit and took photos of frost crystals while I waited. They were very feathery.

Eventually I did get out there and found a beautiful warm and sunny day. Warm was 35 degrees but since last February saw below zero temperatures nearly all month long 35 degrees seemed like a gift.

I saw that a bike with balloon tires had gone through the snow. I’ve heard that the tires on them are underinflated, and that these bikes can go just about anywhere. It seems as if it has taken a good part of my lifetime for bikes to get back to where they were when I was a boy. I can remember them with fat balloon tires that always seemed to be underinflated back then, but we just rode them on the streets.

There is a pasture for horses that runs for a short way along one side of the trail and on the far side of it what I think was little bluestem grass (Schizachyrium scoparium) glowed beautifully in the sunshine. I love the golden color that some grasses have when they’re “dead.”

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) can grow as a shrub or a vine. In this case it grew as a vine on a tree trunk and its white berries gave away its identity, even in winter. I’m glad I saw the berries before I touched the tree trunk. You can catch a good case of poison ivy rash even when the plants have no leaves on them and as general rule I try not to touch plants with white berries. Poison ivy hasn’t ever bothered me much but there is always a first time. Some people get it so badly they have to be hospitalized. Over 60 species of birds are known to eat poison ivy berries, so the toxic part of the plant must have no effect on them.

A gall wasp made a perfectly round escape hole in its near perfectly spherical oak gall. It is said that oaks carry more galls than any other tree. This example is a marble gall.

White pines (Pinus strobus) have shown me that I can use their sap as a kind of thermometer in the winter because the colder it gets, the bluer it becomes. This example was sort of a medium blue which kind of parallels our almost cold winter. I’ll have to look at some if the temperature plunges next weekend as forecast.

Snowmobile clubs have built wooden guardrails along the sides of all of the train trestles in the area to make sure that nobody goes over the side and into the river. That wouldn’t be good, especially if there was ice on the river. Snowmobile clubs work very hard to maintain these trails and all of us who use them owe them a great debt of gratitude, because without their hard work the trails would most likely be overgrown and impassable. I know part of one trail that hasn’t seen any maintenance and it’s like a jungle, so I hope you’ll consider making a small donation to your local club as a thank you.

Years ago before air brakes came along, brakemen had to climb to the top of moving boxcars to manually set each car’s brakes. The job of brakeman was considered one of the most dangerous in the railroad industry because many died from being knocked from the train when it entered a trestle or tunnel. This led to the invention seen in the above photo, called a “tell-tale.” Soft wires about the diameter of a pencil hung from a cross brace, so when the brakeman on top of the train was hit by the wires he knew that he had only seconds to duck down to avoid running into the top of a tunnel, trestle, or other obstruction. Getting hit by the wires at even 10 miles per hour must have hurt some, but I’m sure it was better than the alternative.

I’ve spent over 50 years wondering what these wires were called and was able to find out just recently. I also discovered that though tell-tales were once seen on each side of every trestle and tunnel, today they are rarely seen. The above photo shows the only example I know of and I chose to walk this particular section of rail trail because of it.

There is a nice view of the Ashuelot River from the trestle. It’s very placid here but its banks seem wild and untamed, and it’s easy to imagine that this is what it looked like before colonists came here.

Though there is surface rust on the ironwork of the trestle they were built to last and I wouldn’t be surprised if it looks the same as it does now after standing for another 150 years. You can see in this photo that the rust is just a very thin coating on the heads of the rivets.

Stone walls marked the property line between landowner and railroad. I’ve tried to find out how wide railroad rights of way are but it seems to vary considerably. I’ve read that the average setback on each side is 25 feet from the center of the nearest rail. Add 10 feet or so for engine width and you have a 60 foot wide rail trail right of way, which seems about right in this region of the country.

On my way back I was passed by a lady on snowshoes who asked me what I was taking photos of. “Anything and everything,” I told her, but I really wasn’t planning on taking her photo until I realized that she might give the place a sense of scale. This photo shows how, though the right of way might be 60 feet wide the sides aren’t often flat, so this might leave an actual trail width of only 20 feet.

Railroad tracks have always been a great place to go berry picking. Raspberries, blackberries and blueberries can all be found in great abundance along most trails. In this section lowbush blueberry bushes (Vaccinium angustifolium) looked spidery against the snow.

On this trip something I had been wondering about for a few years was finally put to rest, and that was the question do maple dust lichens (Lecanora thysanophora) only grow on maple trees? The one pictured was growing on a beech tree, so the answer is no. So why are they called maple dust lichens? That question I don’t have an answer for.

I saw the biggest amber jelly (Exidia recisa) fungus I’ve ever seen out here. It was as big as a toddler’s ear and felt just like an ear lobe. As usual it reminded me of cranberry jelly, which isn’t amber colored at all.

I saw the sun lighting up the orange brown leaves of this sweet fern from quite a distance away. Sweet fern is a small shrub with incredibly aromatic leaves which release their fragrance on warm summer days. They can be smelled from quite a distance and are part of the summer experience for me. Though they aren’t ferns their leaves look similar to fern leaves. They are actually a member of the bayberry family and the leaves make a good tasting tea. Native Americans made a kind of spring tonic from them and also used them as an insect repellant. On this day I just admired their beauty, glowing there in the sun.

A fallen branch poked up out of the snow as if it had been waiting for me to come along. It showed off what looked from a distance like little orange flowers, but I knew that couldn’t be.

They weren’t flowers but they might as well have been because they were just as beautiful. I’m not sure but I think they were older examples of milk white toothed polypores, which are known to brown with age. These hadn’t reached the brown stage but they were very orange and very interesting.

Each living thing gives its life to the beauty of all life, and that gift is its prayer. ~Douglas Wood

Thanks for coming by.

A Walk Along the Ashuelot River

Posted in Nature, Scenery / Landscapes, Things I've Seen, tagged Ashuelot River, Bitter Wart Lichen, Black Eyed Susan, Canon SX40 HS, Common Witch Hazel, Deer Tongue Grass, Early Spring Plants, Gord Glaze Moss, Keene, Native Plants, Nature, New Hampshire, NH, Panasonic Lumix DMC-527, Poison Ivy Berries, Spring, Staghorn Sumac, Swanzey, White Pine on March 26, 2014| 46 Comments »

Canada geese are flying in pairs up and down the Ashuelot River again and the ice that covered it for a while in this spot has melted. The deep snow that has kept me off its banks has melted enough so it is once again possible to explore, and it’s a great feeling because I’ve missed being there. The going can still be difficult though. Just after I snapped the above photo we saw snow squalls, so these shots had to be taken over 2 or 3 days.

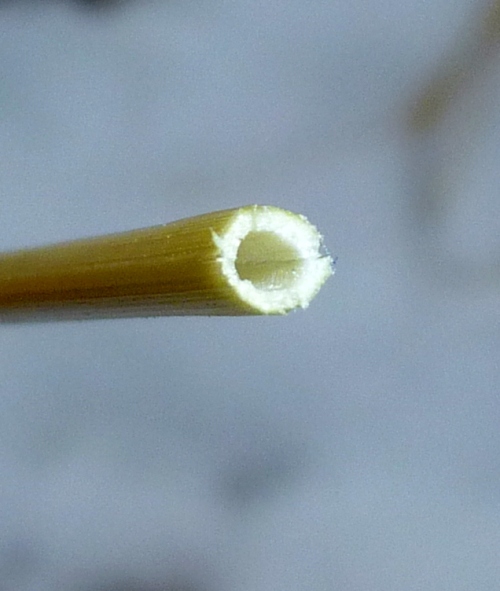

One of the first things I saw was a broken grass stem, so I thought I’d see how close I could get with my camera.

Black eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta) still have plenty of seeds on them. With a winter like the one we’ve just had I would expect every food source to be stripped clean but there are still large amounts of natural bird feed out there. I’m not sure what to make of it. Maybe it happens every year and I’ve just never noticed.

Something I haven’t seen here before was a large clump of cord glaze moss (Entodon seductrix). This moss is a sun lover and it was growing on a stone in full sun. It is also called glossy moss because of the way it shines. Its leaves become translucent when wet and a little shinier when dry, but unlike many other mosses its appearance doesn’t change much between its wet and dry states.

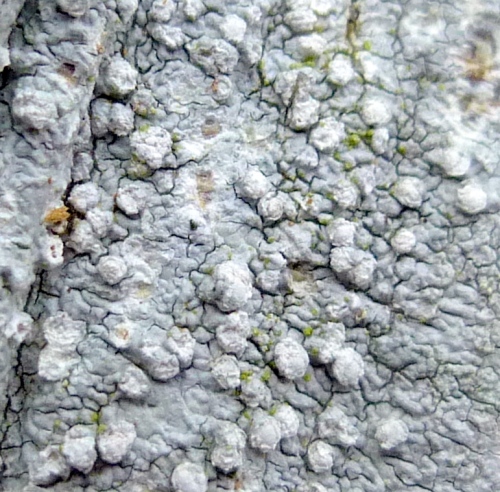

Bitter wart lichen (Pertusaria amara) is a rarity here. The only one I know of grows on the limb of an old dead American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) tree that still stands near the river. When I went to visit this lichen I noticed with dismay that all of the bark is falling from the dead limb that it grows on, so this might be that last shot I get of this particular example.

This close up shot of the bitter wart lichen shows the darker gray, deeply fissured body (thallus) and whitish fruiting bodies (apothecia) that erupt from it. The apothecia look like warts and are how this lichen gets its common name. From what I’ve read about this lichen the apothecia are rarely fertile, and that might explain why I’ve only seen just this one. The “bitter” part of the common name comes from its bitter taste. Not that I’ve tasted it-I just take the lichenologist’s word for it.

There is a lot of dead deer tongue grass (Dichanthelium clandestinum) showing in places, all beaten down by the heavy snow load. This grass is tough and it amazes me how this can all just disappear into the soil in just a few short months. This grass gets its common name from the way its leaves resemble a deer’s tongue.

White pines (Pinus strobus) are showing signs of sticky new growth. In his writings Henry David Thoreau mentioned the white pine more than any other tree, and once wrote of being able to see distant hills after climbing to the top of one. The tallest one on record was about 180′ tall.

Staghorn sumacs (Rhus typhina) grow along the edges of the woods that line the river and their buds are swelling. Up close the hairy, first year branches of this tree look more animal than plant. Another name for staghorn sumac is velvet tree, and that’s exactly what it feels like.

Along this stretch of river is where the inner bark on dead staghorn sumacs is a bright, reddish orange color. I’ve looked at dead sumacs in other locations and have never seen any others with bark this color. I’ve read descriptions that say the inner bark is “light green and sweet to chew on,” but no reference to its changing color when it dries, so it is a mystery to me. If you’re reading this and know something about sumac bark I’d love to hear from you.

Native witch hazels (Hamamelis virginiana) also line the banks of the Ashuelot in this area. This is a shot of the recently opened seed pods, which explode with force and can throw the seeds as far as 30 feet. I’ve read that you can hear them pop when they open and even though I keep trying to be there at the right time to see and hear it happening, I never am.

There are no man made trails here but there is a very narrow game trail which in places is crowded by poison ivy plants (Toxicodendron radicans) on both sides, so I always wear long pants when I come here. Even with longs pants one early spring I knelt to take a photo of a wildflower and must have landed right on some poison ivy because my knees itched for two weeks afterward. I’m lucky that the rash stays right on the body part that contacted the plant and doesn’t spread like it does on most people. In the above photo are the plant’s berries looking a little winter beaten, but which will also give you a rash if you touch them. This is a good plant to get to know intimately if you plan on spending much time in the woods because every part of it, in winter or summer, will make you itch like you’ve never itched before.

The river seems so happy now that the dam that stood here for more than 250 years is gone. Trout and other fish have returned. Eagles once again fish it, ducks and geese swim in it, and all manner of animals visit its shores.

I can remember when the Ashuelot ran a different color each day because of the dyes that the woolen mills discharged directly into it. I’ve seen it run orange, purple, and everything in between. It was very polluted at one time but thankfully it was cleaned up and today tells a story of not only how we nearly destroyed it, but also how we saved it. Knowing what I do of its history, it’s hard not to be happy when I walk its banks.

The mark of a successful man is one that has spent an entire day on the bank of a river without feeling guilty about it. ~Chinese philosopher

Thanks for stopping in.

Things I’ve Seen

Posted in Nature, Things I've Seen, tagged Bears Head Fungus, bumblebee, Eastern Chipmunk, Forked Blue Curl Seeds, Keene, Laurel Sphinx Caterpillar, Native Cranberry, Native Plants, Nature, New Hampshire, New York Fern Sori, NH, Pigskin Puffball, Poison Ivy Berries, Poison Ivy Fall Color, Purple Stemmed Aster, Turkey Tail Fungus on October 23, 2013| 37 Comments »

Here are a few more of those things I’ve seen on the trail that didn’t make it into other posts.

This chipmunk saw me but just sat on his rock, not making a sound. After I got home and saw the photo I wondered if maybe he was too chubby to be able to run away.

It’s been a good year for all kinds of fruits and nuts, including acorns. Maybe that’s why the chipmunk is so chubby.

This caterpillar was happily eating all the leaves from my lilac. The helpful folks over at bugguide.net tell me that it is a laurel sphinx caterpillar (Sphinx kalmiae). It was as big as my index finger and had a wild looking horn. In this stage the caterpillar is nearly ready to stop feeding and start looking for soil to pupate in. The laurel sphinx moth is gray brown with brownish yellow wings-not nearly as colorful as the caterpillar.

I’m seeing many more turkey tail fungi (Trametes versicolor) this year than I did last. They are very colorful this year. Polysaccharide-K, a compound found in these fungi, has shown to be beneficial in the treatment of gastric, esophageal, colorectal, breast and lung cancers.

Lion’s mane, bear’s head, monkey head, icicle mushroom-call it what you will, Hericium americanum is a toothed fungus that is always fun to find in the woods. This mushroom is edible but unless you can be 100% sure of your identification you should never eat a wild mushroom. Bruce Ruck, director of drug information and professional education for New Jersey Poison Control at Rutgers, says it better than I: “Eating even a few bites of certain mushrooms can cause severe illness. Unless you are a mycologist, it is difficult to tell the difference between a toxic and non-toxic mushroom”

Speaking of toxic mushrooms, here’s one now. This is the toxic pigskin puffball (Scleroderma citrinum), which isn’t really a puffball at all but an earth ball. Earth balls are always hard to the touch and never “squishy” like puffballs. If you eat them they won’t kill you, but they can make you quite sick. In the book A Northwoods Companion author John Bates says that “a single large puffball contains so many spores that if every spore germinated to an adult for two generations, the resultant mass would be 800 times the volume of the earth.” But what is considered large? The largest puffball ever found was nearly 5 feet across.

Forked bluecurl seeds (Trichostema dichotomum) are so small that the only way I can see them is in a photo. This plant has beautiful blue flowers with long, curving, blue stamens. It is an annual, so it has to grow new from seed each year. Two or three seeds nestle in a basket shaped, open pod and sometimes I take a few seed pods home, hoping that I can get the plant to grow in my yard. So far I have had limited success, even though I’ve provided the same growing conditions.

Many of the woodland ferns have lost their chlorophyll and have gone pale now. I recently turned one of these pale fronds over and found all these tiny sori. These are clusters of even tinier sporangia which are the spore masses where the fern’s spores are produced. I think this one might be a New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), but to be honest I didn’t pay close enough attention to its identifying characteristics to be certain.

Even poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) has to get in on the fall show. Poison ivy can grow in the form of a shrub or a vine and in this case it had twined its way up a birch tree. Beautiful to look at but you don’t want to touch it. The oils in the plant form a complex with skin proteins and interrupt the chemical signals that the skin sends to the rest of the body. The area of exposed skin is then viewed as foreign and the body attacks it, which results in a very itchy rash that can becomes sore and bleed. And if that isn’t bad enough it is also systemic, meaning you can touch the plant with your hand and end up with a rash on your leg or any other part of your body. Some internal cases of poison ivy- that can come from eating the leaves –have been fatal.

I found another poison ivy on another tree that had lost all its leaves and had just its berries showing. Over sixty species of birds have been documented as eating these berries. Apparently birds are immune to its toxic effects.

The native cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) have ripened, but you’ll sure get your feet wet harvesting them. I find them growing in a bog in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire. The pilgrims named this fruit “crane berry” because they thought the flowers looked like sandhill cranes. They were taught how to use the berries by Native Americans, who used them as a food, as a medicine, and as a dye.

One cool day I found this bumblebee curled into a ball in an aster blossom and I thought it had died there but, as I watched I could see it moving very slowly. I’ve read that bumblebee queens hibernate in winter, but I can’t find out what happens to the rest of the hive.

In all things of nature there is something of the marvelous. ~Aristotle

Thanks for coming by.