I’d heard rumors about more rail trail improvements going on here and there, so I thought I’d go and see how they were coming along. This trail, for local people who’d like to follow it, runs between the Ashuelot River and Eaton Road in Swanzey. I had also heard that there were also some serious washouts along this trail during the heavy rains and flooding last summer, and I hoped that part of the rumor wasn’t true.

The first improvement I noticed was that the drainage channels had been cleaned out. This was good and bad, because though the water would flow better, the cleaning out had widened the ditch I had to cross over. I stood at the top of the hill you see on the right, wondering what the best way was for me to get to the other side. I thought about running and jumping but then I decided to just walk down the hill and step over the ditch. Unfortunately when I lifted my right foot to step over it my left foot slipped in the mud and I landed with a splash and both feet in the water.

As I stepped up out of the ditch I noticed this boulder in a hazelnut thicket. I thought it was odd that I had never seen it before since I come here to get photos of hazelnut flowers in spring. Even more puzzling was the round spot on it. I couldn’t tell if it had been painted on or if it was natural. Back in my rock and mineral hunting days I split open a honeydew melon size rock that had a large, perfectly round spot in its center that looked just like this, caused by iron deposits I believe. I saved that rock and still have it but this one was too big to carry.

Christmas ferns are flattening themselves against the earth for warmth as they do every year. They’ll stay green under the snow all winter and were named “Christmas” ferns by early settlers who brought them inside in winter. The long, cold, dark winters and several feet of snow must have been hard for them to bear. I would imagine that any green growing thing would have lifted their spirits.

Raspberry leaves lit up this day. Because of the blueish stems I believe this is a black raspberry.

Neat rows of small holes told me a sapsucker had visited this maple tree. Sapsuckers are in the woodpecker family. When sap is running many other birds, bats, insects, and animals sip the sap that runs from these holes, so they are an important part of the workings of the forest. This tree has problems with rot and looked to be ready to fall over, so I doubt much sap will weep from those holes. I usually see sapsucker holes on wild fruit trees. These may be the first I’ve seen on a maple.

The washouts proved to be reality rather than rumor, and this was a big one. What happened was, for the first time in 150 years the stone box culvert under the trail couldn’t handle all the water trying to flow through it at once and the force of the water washed soil away.

For those who have never seen one, this is a photo of a box culvert taken a few years ago. The railroad would put down a thick granite slab for a floor, then add two side walls and a roof, and then pile massive amounts of gravel and packed earth on top of the culvert to make a level bed. Length depended on the width of the railbed. They’re built to last; beyond sturdy, and I’ve never seen one fail. But the railroad engineers didn’t have a crystal ball and they had no way of knowing what type of storms there would be in a century and a half into the future. Today we don’t have to see very far into the future to know that we’re going to have to re-think a lot of our infrastructure. Culverts of any kind should be a priority because there is a lot more water trying to flow through them now and they can’t handle it.

If you see a stream that seems to come out of nowhere when you’re on a rail trail you can be sure there is a box culvert right under where you’re standing. The stream seen here is maybe 30 feet below the rail bed so you can imagine how much soil had to be brought in to raise and level it. Box culverts were built on site by stone masons using granite taken from nearby ledges or boulders and they were built according to how big the stream was. The one in the previous photo, which is the one this stream runs through, is about 2 feet square.

And there are a lot of box culverts along this section of trail.

Here was a huge washout that didn’t affect the trail because it was on the far side of a deep ravine. It was interesting because I could see how sandy soil had been deposited on top of a bed of gray clay. Clay deposits on the banks or beds of rivers are called alluvial deposits. Since the only way that clay could have gotten there was to be deposited by the river, it shows that the river channel was once quite far from where it is now. Time and pressure will eventually turn the clay into shale.

I’ve heard all kinds of opinions on how long it takes to build up an inch of topsoil (100-1000 Yrs.) and in the end I doubt anyone really knows for sure because the rate depends on many different factors. But for the sake of argument I’ll say 500 years. From where I stood it looked like there was about 4 feet of topsoil over the clay bed, so 48 inches X 500 years = 24,000 years since that clay last saw the light of day. Of course that is provided the area wasn’t disturbed by man. If someone trucked all that soil in at some point that changes the whole scenario but it’s safe to say it has been there a long time. Closer to where I lived along the Ashuelot there was an exposed clay deposit in the river bank. I used to dig the clay and make all kinds of things with it but of course I had no way to fire it so it all just crumbled away.

I saw the first good example of a maple dust lichen this year. Some lichens wait until cold weather to really show themselves but I don’t know if this is one of those. This lichen’s appeal is in its simplicity; just a pale greenish body with a white fringe around it; simple beauty. The white fringe is called the prothallus and seeing it is a great way to identify this lichen. Though named the maple dust lichen it grows on several species of tree.

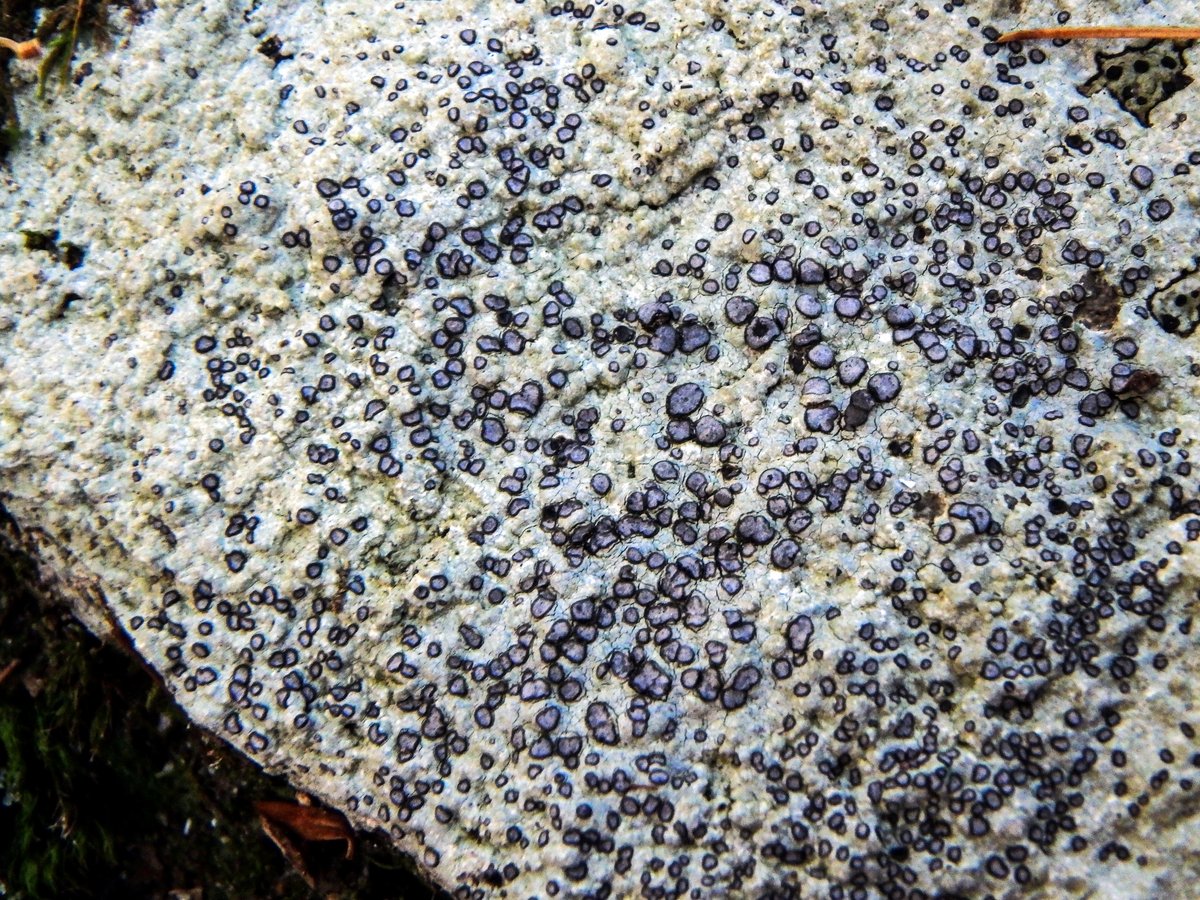

Script lichens are visible year round as white spots on trees but only when it gets cold enough do their squiggly apothecia appear. They’re usually black against the body but these were on the gray side because I think they had just appeared. I’ve wondered for years why some lichens, ferns, mosses and even some fungi wait until winter to release their spores. There has to be some benefit in it but I’ve never been able to even guess what it is. Figuring that out would be a nice feather in a biology students cap, I would think.

I tend to notice delicate fern moss more than others at this time of year because they always look bright orange. That’s due to color blindness, so I always have to ask my color finding software what color it really is. In this case it says yellow-green. From a distance I thought it was tree skirt moss, but it fooled me in that way too.

It’s easy to see how the shagbark hickory tree got its name. There are quite a few of them growing along this trail. These two were quite young; too young to drop nuts, I would guess.

And here was another trail washout, bigger than the first. I’m not sure who is responsible for repairing things like this but they have quite a job ahead of them.

It’s a long, long way down to the river from up here and that’s quite a pile of rubble and trees that washed away in the flooding when all the rain tried to get to the river. Every brook, stream and trickle eventually finds its way to the Ashuelot River in this part of the state, and the Ashuelot eventually empties into the Connecticut River which in turn empties into the Atlantic Ocean, so we’re sending a lot of soil to the sea.

Ocher Bracket Fungi grew on a log. Though these bracket fungi resemble turkey tails in shape and habit they don’t show the same color variations. The versicolor part of the scientific name of turkey tails means many colors, and these brackets had only various shades of a single color, which was a kind of yellowish brown.

As I always do when I follow this trail, I saw lots of partridge berries and I surprised myself by being able to get a shot of this pea size berry’s two dimples with my cell phone. The dimples are left by the plant’s two flowers, which share a single ovary. I find this little ground hugger’s leaves very pleasing; they always look like hammered metal.

The ovary found at the base of the flowers, as can be seen here. When the ovary becomes a berry, that berry grows around the base of the flowers, which leave dimples in it. This is an unusual arrangement; the only other plant I know of that does this is the fly honeysuckle, which is one of the first shrubs to bloom in spring.

This sign wasn’t a big surprise.

I had heard that some of the rail trail trestles were being re-decked and that’s what was going on here. This work is all done by volunteers, many from snowmobile clubs, so they deserve our thanks. (And our donations if we can afford them.)

It looks like they’re using 4X4 lumber to re-deck this trestle, so that should last a few years. It looked like they were about half done with the decking, but then they’ll also have to replace the guard rails along the sides, which keep people from falling into the river. Since they can probably only work at this on weekends now that it gets dark so early, I think it will be a while before I cross this trestle again. If I kept following this trail in this direction for a few more miles I’d walk right behind the house I grew up in in Keene.

Here were the old guardrails.

I wanted to get a shot of the river from the trestle but that wasn’t going to happen on this day so I had to settle for this shot. The way the river rises and falls so quickly these days makes it hard to know exactly what “normal” is anymore. Raging or placid, I can always count on is its beauty.

The mark of a successful man is one that has spent an entire day on the bank of a river without feeling guilty about it. ~Chinese philosopher

Thanks for stopping in.