Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

- Describe the different types of prescription drug coverage available to Medicare patients

- Explain the patient costs associated with Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage

- Demonstrate use of a patient’s Medicare Part D formulary to determine the appropriate type of coverage determination

- Identify prescriptions that Medicare Part D does not cover

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to:

- Describe the different types of prescription drug coverage available to Medicare patients

- Explain the patient costs associated with Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage

- Identify the types of coverage determinations available for Medicare Part D prescriptions

- Outline the timeframes involved in Medicare Part D coverage determination and appeal decisions

Release Date: March 15, 2024

Expiration Date: March 15, 2027

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $7

Pharmacy Technicians: $4

There is no funding for this CE.

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-24-015-H04-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-24-015-H04-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 24YC15-XTK93

Pharmacy Technician: 24YC15-KFV48

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-24-015-H04-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Lori R. Donnelly, PharmD

Consultant

BluePeak Advisors

Chardon, OH

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Dr. Donnelly is a consultant with Blue Peak Consultancy that assists those with government healthcare concerns. Any conflict of interest has been mitigated.

ABSTRACT

Millions of Americans are enrolled in Medicare Part D, with hundreds of specific Part D plans available across the country. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regulates Part D coverage. Part D plans must submit their plan costs and formularies, including formulary restrictions, to CMS for annual approval. Patient costs for Part D coverage vary based on the specific choice of plan and the benefit phase. All Part D plans must provide a process for requesting coverage of prescription medications that are not on the formulary or on the formulary with restrictions. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are valuable resources and can advise Part D patients and prescribers about prescription costs and the options available for non-covered medications.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

As of April 2023, more than 51 million Americans were enrolled in prescription drug coverage through Medicare, with the number of enrollees steadily increasing every year.1 Private insurance companies contracted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provide Medicare prescription drug coverage. Although specific plans’ details differ, CMS requires that all plans offer certain features.

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can assist patients in navigating these features to maximize their prescription benefits. This continuing education activity will review the types of Medicare prescription drug coverage, associated patient costs, formulary structure, and the options available when a patient’s Part D plan does not cover a medication.

MEDICARE AND PRESCRIPTION DRUG COVERAGE

CMS provides “Original Medicare” to most Americans aged 65 and older. Original Medicare includes2:

- Part A: Most Americans are eligible for Medicare Part A at no additional cost, as long as they or their spouses have paid sufficient Medicare taxes. Medicare Part A includes coverage for inpatient hospital stays, hospice, and skilled nursing facility care.

- Part B: Medicare Part B is optional and usually requires additional fees. Part B coverage includes outpatient and home health care, preventive services, and durable medical equipment.

CMS contracts with private insurance companies to provide prescription drug coverage. Individuals enrolled in Original Medicare may purchase a standalone Part D Prescription Drug plan (PDP) for outpatient prescription drug coverage.

Rather than using CMS coverage, individuals may purchase Medicare-approved private insurance called Medicare Advantage (MA), also known as Part C. With this arrangement, the MA Plan supersedes Medicare Part A and Part B for most coverage. MA plans often have lower patient costs and extra benefits compared to Original Medicare but may have fewer covered hospitals and physicians.2 Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MAPD) plans are MA plans that include prescription drug coverage and eliminate the need for a separate PDP.

SIDEBAR: Patient Costs Defined

Monthly Premium: a monthly payment that maintains enrollment in the plan; not impacted by deductible, copay, or coinsurance amounts

Annual Deductible: a yearly dollar amount the patient pays before insurance starts to contribute

Copayment (or Copay): a specific, pre-determined dollar amount the patient pays for each prescription, office visit, or other type of care after satisfying the deductible

Coinsurance: an alternative to a copay, the percentage of the total cost the patient pays for each prescription, office visit, or other type of care after satisfying the deductible

Medicare plans are associated with various costs to the enrollee (see SIDEBAR: Patient Costs Defined). Individuals with income higher than a predefined threshold pay a higher premium for their Part B coverage due to Medicare’s Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA). IRMAA does not change any of the other costs associated with Medicare coverage. CMS may also issue a late enrollment penalty (LEP) to people who do not sign up for Part D (from either a PDP or MAPD) as soon as they become eligible for Medicare. Once assigned, CMS adds the LEP to the patient’s monthly Part D premium for the remainder of their enrollment in Part D, regardless of which Part D plan they choose. Even people not actively taking prescription medications should consider choosing a Part D plan with a low monthly premium and/or no annual deductible to avoid incurring LEP.2

Individuals and couples with incomes and assets less than an annual threshold set by CMS may qualify for a Low Income Subsidy (LIS), also known as “extra help.” For people who qualify, the LIS reduces or eliminates the Part D monthly premium, deductible, and copay/coinsurance. CMS automatically enrolls most qualified patients into extra help, but a manual application process is also available. Pharmacy personnel should refer patients to 1-800-MEDICARE or https://www.medicare.gov/basics/costs/help/drug-costs to see if they qualify for LIS.3

Once a patient decides between Original Medicare or MAPD coverage, the next step is choosing a specific plan. CMS provides a comprehensive platform, called Medicare Plan Finder (MPF) for patients to shop and compare costs for PDP and MAPD plans. Patients can enter their medication list and see detailed cost information for each prescription. MPF also includes information about participating pharmacies and Star Ratings, a system CMS uses to measure each Part D plan’s performance in the areas of customer service, member experience, drug safety, and drug pricing accuracy. CMS rates plans on a scale of one to five stars, with five stars indicating the highest level of performance.4

The MPF tool is located at www.medicare.gov/plan-compare.

It is not necessary for pharmacy personnel to distinguish between MAPD and PDP coverage before processing prescription claims. The member’s prescription drug card provides the details needed to submit pharmacy claims to either type of Part D plan. If the member’s prescription drug card is not available, CMS provides a process known as an E1 transaction that returns Part D coverage information using basic demographic information. Pharmacists and technicians should consult their employer’s training materials for specific instructions on submitting an E1 transaction.5

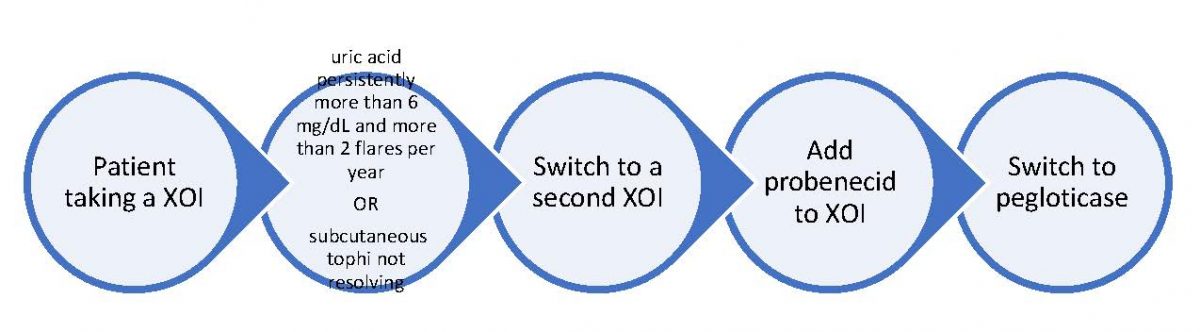

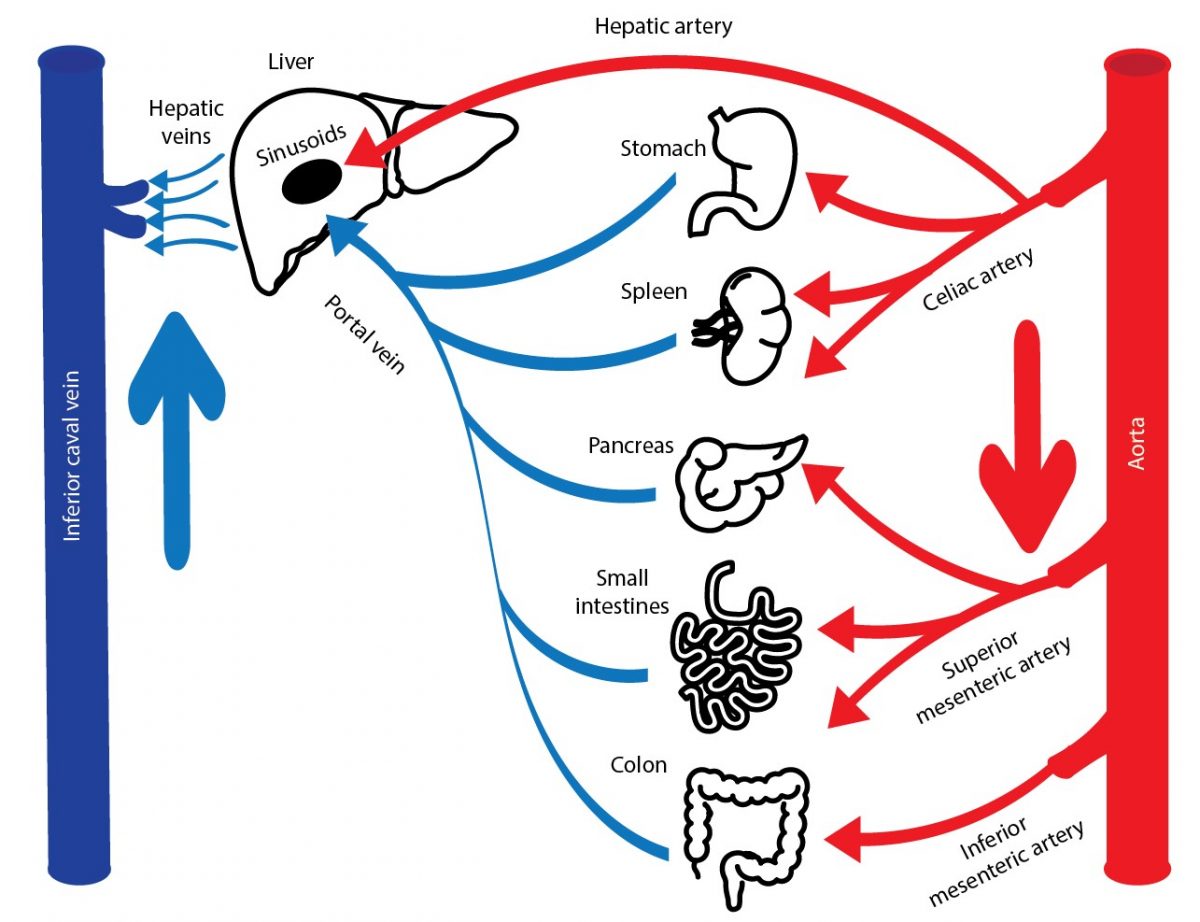

The Part D Coverage Cycle

The Part D coverage cycle runs January to December each year. Regardless of when an individual reaches each phase of coverage, summarized in Figure 1, they start over in the deductible phase each year on January 1st. Only “True Out-of-Pocket” (TrOOP) costs as defined by CMS go toward the thresholds to move patients through each of the four coverage phases. Patient costs excluded from TrOOP are6

- Medications not covered by the Part D plan

- Prescriptions obtained at non-participating (i.e., out-of-network [OON]) pharmacies, except those specifically allowed under the Part D plan’s rules

- Costs reimbursed by an organization other than the Part D plan

PAUSE AND PONDER: Some patients with lower prescription costs do not complete their annual deductible until November or December. They are surprised when their out-of-pocket costs increase again in January. How would you explain the increase?

Patients with higher prescription costs may also be subject to the coverage gap, commonly known as the “Donut Hole” (see SIDEBAR: Explaining the Donut Hole). The coverage gap occurs when a patient’s prescription drug costs exceed a defined threshold under Medicare Part D. In the coverage gap, a patient’s out-of-pocket cost for brand name prescriptions may increase. 7 Patients with very high prescription drug costs may reach the end of the coverage gap to enter catastrophic coverage, where they pay nothing out of pocket. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 removed patient costs from the catastrophic phase starting in 2024 and eliminated the coverage gap starting in 2025.8

SIDEBAR: Explaining the Donut Hole

Have you ever wondered why the Medicare Part D coverage gap is called the “Donut Hole?”

Imagine a giant donut, a circle with a hole in the middle, big enough to drive through. Half of the donut is plain, but the other half has frosting and sprinkles. In January, you start driving in a straight line through the plain half of the donut, toward the frosted half. Your drug costs determine your speed.

The plain half of the donut represents the annual deductible and initial coverage phases where you are subject to normal coverage amounts.

If high drug costs cause you to drive faster, you exit the plain half of the donut and enter the donut’s hole before the end of the year. You are now driving where there is no donut, and you must pay more than the normal amount for brand name drugs.

If your drug costs are high enough that you speed to the other side of the hole before the end of the year, then you enter the frosting and sprinkles half of the donut. Frosting and sprinkles represent the additional Part D contributions in the catastrophic phase and you pay nothing out of pocket.

Unfortunately, your car has only a 365-day warranty, so when January comes, you must start all over at the plain side of the donut.

An annual bidding process determines the specific costs for each Part D plan. Each year, CMS sets limits and thresholds for certain aspects of Part D coverage but allows flexibility within these parameters for both PDP and MAPD plans. Insurance companies submit bids that demonstrate how their plans comply with CMS’s annual limits and thresholds. The financial information that contributes to each plan’s annual bid is highly complex, and CMS can either accept or reject each bid.

As part of the annual bidding process, CMS defines standard prescription drug coverage. For a “basic” Part D plan, a bid must either match or be financially equivalent to the CMS definition of standard coverage. Table 1 provides the 2023 and 2024 standard benefit parameters, as defined by CMS.9

Table 1. Limits and Thresholds for 2023 and 2024 Medicare Part D Plans9

| 2023 | 2024 | |

| Annual Deductible Limit | $505 | $545 |

| Initial Coverage Limit (starts the coverage gap) | $4660 total drug costs | $5030 total drug costs |

| Out-of-Pocket Limit (ends the coverage gap and starts catastrophic phase) | $7400 patient cost | $8000 patient cost |

Insurance companies may also offer “enhanced” Part D plans with coverage that is more robust than the defined standard. Most plans with enhanced coverage have higher monthly premiums compared to basic plans but offer corresponding advantages such as reduced deductibles, lower copays/coinsurance, and lower costs in the coverage gap.

Individuals should choose their Part D plans carefully because they can only sign up or change Part D plans during certain periods2:

- During the 3-month initial enrollment period that starts 1 month before and ends 1 month after an individual’s 65th birthday; coverage starts the month after initial enrollment

- During the annual open enrollment period that runs from mid-October to early December each year; coverage starts on January 1 of the following year for people who enroll during annual open enrollment

- During the Medicare Advantage open enrollment period that runs from January through March each year; during this time, CMS only allows certain types of changes

- During special enrollment periods for qualifying events such as relocation or the loss of employer or Medicaid coverage. Natural disasters that disrupt the initial or annual enrollment period may also create special enrollment periods

Prescription Coverage Under Medicare Parts A and B

Original Medicare provides prescription drug coverage under very limited circumstances and CMS prohibits Part D from covering anything covered under Medicare Parts A or B.

Medicare Part A covers hospice care, including medications related to the hospice diagnosis. Hospice providers receive payment for these medications from CMS and are responsible for paying the pharmacy. Medicare Part D is prohibited from covering medications related to any hospice diagnosis.10

Medicare Part B provides the only coverage options for some items, such as diabetic testing supplies and certain vaccines. Coverage for other items may fall under Part B or Part D, depending on the specific circumstances. Table 2 compares Part B and Part D coverage for the most common examples.10

Table 2. Medicare Part B and Part D Coverage of Common Products

| Product(s) | Part B Coverage | Part D Coveragea |

| Nebulizer Solutions (such as albuterol sulfate and ipratropium bromide) | For patients residing at home. | For patients residing in a long-term care facility. |

| Influenza, Hepatitis B, Pneumonia, and Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccines | Yes | No |

| Immunosuppressants (such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil) | When used to prevent rejection of a Medicare-covered transplant. | When used for a medically accepted indication other than a Medicare-covered transplant. |

| Oral Anti-Cancer Drugs (such as cyclophosphamide and methotrexate) | When used to treat cancer. | When used to treat a medically accepted indication other than cancer. |

| Oral Anti-Emetic Drugs (such as ondansetron and promethazine) | When used to treat or prevent chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. | When used to treat or prevent medically accepted indications other than chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. |

| Insulin | When used in an insulin pump. | When not used in an insulin pump. |

| Diabetic Testing Supplies (such as test strips and lancets) | Yes | No |

| Insulin Injection Supplies (such as needles and alcohol swabs) | No | Yes |

| aCoverage may be subject to formulary restrictions. | ||

Part D plans are responsible for rejecting pharmacy claims for medications that may be covered under Part A or Part B. Pharmacy personnel should refer to claim reject messaging and redirect the claim appropriately.

Other Prescription Drug Coverage

Most people who qualify for Medicare are covered by some combination of Parts A, B, C, and D as described above. However, other prescription drug coverage options are available under special circumstances:

- Employer Group Waiver plans (EGWPs): Employers may choose to provide prescription drug coverage for their retirees by contracting with a Part D plan for EGWP coverage. Retirees with EGWP plans that start as soon as they become eligible for Medicare are exempt from LEP. When providing an EGWP plan for their retirees, employers may also add additional benefits paid either through Part D or by the employer themselves.11

- Medicare Supplemental Insurance (Medigap): Medigap coverage helps with costs not covered by Medicare Parts A and B, such as copays and deductibles. Certain Medigap plans also help with skilled nursing facility or hospice costs and emergency care while traveling outside of the United States. Individuals who enrolled in Medigap prior to 2006 may have prescription drug coverage included, but those who are newer to Medigap should purchase separate Part D coverage to avoid LEP.12

- Employer Coverage: Individuals who are actively employed (not retired) may have coverage through their employer to replace Medicare or use Medicare as secondary coverage. Covered employees are exempt from the LEP if the employer coverage is equivalent to at least a basic Part D plan.2

- Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA): People who have recently separated from an employer may be eligible for COBRA. Individuals enrolled in COBRA may still be subject to LEP because COBRA is usually not equivalent to Medicare coverage.2

- Medicaid: People with low incomes who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare receive the LIS and have Part D coverage with reduced patient costs. In most cases, Medicare pays first and Medicaid helps with remaining costs.2

- Manufacturer Discount Programs: Many drug manufacturers provide coupons, discount cards, and patient assistance programs to help cover their products’ cost. Federal law prohibits using these manufacturer payments in combination with Medicare prescription drug coverage.13 Medicare patients may choose manufacturer coupons or patient assistance programs for certain prescriptions only when they do not use their Part D coverage.

- Prescription Discount Cards: Unlike manufacturer discounts, which are limited to products produced by that manufacturer, prescription discount cards offer discounts on a wide range of medications. Also known as “cash cards”, prescription discount cards reduce the cash price of prescriptions, but are not used in combination with insurance, including Medicare.14 Patients who choose a prescription discount card cannot use it in combination with their Part D coverage for the same medication.

MEDICARE PART D FORMULARIES

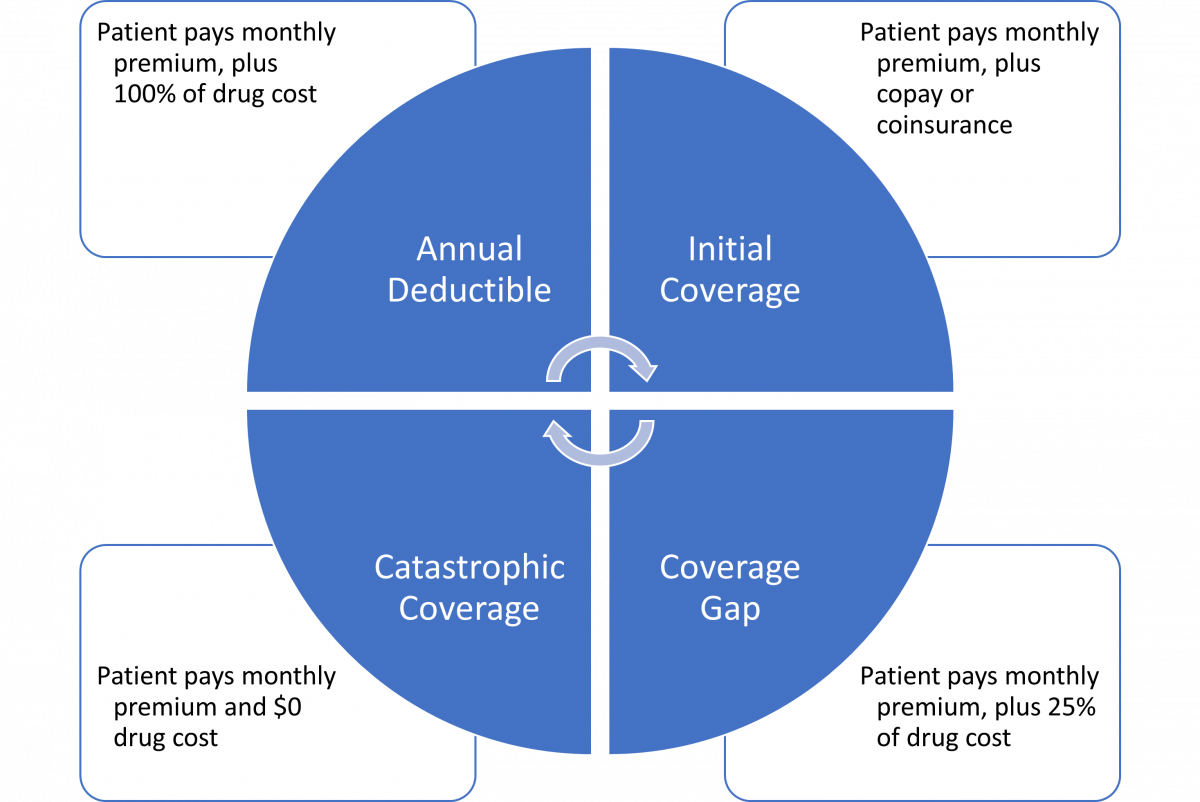

CMS requires Part D plans to maintain a list of covered drugs, called a formulary. CMS reviews each Part D formulary to ensure sufficient coverage under each drug class. The copay or coinsurance for each medication on the formulary is determined by its “tier.” Medications on lower tiers generally cost less than drugs on higher tiers.15 CMS allows some flexibility on how Part D plans define their formulary tiers, so tier structure differs between plans. Figure 2 provides an example of a formulary tier arrangement.

Drug Placement and Formulary Restrictions

Specialty medications are high-cost prescription products used to treat complicated medical conditions. CMS limits the patient cost portion for these medications and Part D plans typically place all specialty mediations into designated formulary tiers.10

CMS requires that Part D plans cover adult vaccines (excluding those covered under Part B) recommended by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices at no cost to the patient, regardless of formulary tier or benefit phase.16

In 2023, CMS began setting a maximum copay for insulin products covered under Part D. Currently, the maximum copay is $35 for a one-month supply and is subject to change on an annual basis. Insulin copays may be lower if a Part D plan includes specific insulin products on a formulary tier where the monthly copay is lower than the CMS maximum. A similar program exists for insulin used in an insulin pump and covered under Part B.16

Part D plans may put restrictions on formulary medications to ensure appropriate coverage and to control costs. CMS reviews the restrictions and will not allow overly restrictive formularies. Plans may place four types of restrictions on formulary medications10:

- Quantity Limit: Quantity limit restrictions define the maximum number of dosage units allowed for a specific time period.

- Step Therapy: Step therapy restrictions require patients to first try a different medication, usually a lower cost alternative, before the prescribed medication.

- Prior Authorization: Prior authorizations require patients to meet specific criteria, which may be as simple as providing the diagnosis or more complicated (e.g., specific lab tests, involvement of a specialist physician).

- Drug Utilization Review (DUR): May be “hard edits” that require a coverage determination or “soft edits” that require the dispensing pharmacist to obtain clinical information and enter a set of codes into the prescription claim.

CMS defines six drug classes—those used to treat disorders where changes or interruptions in therapy involve higher risk—as “protected class.” CMS requires that Part D formularies include most medications within these classes with at least one medication on a preferred tier and no restrictions. Plans are not, however, required to include all variations of each medication (i.e., brand name and generic or immediate and extended-release versions). The six protected classes are10

- immunosuppressants (used to prevent organ transplant rejection)

- antidepressants (used to treat depression)

- antipsychotics (used to treat mental health disorders)

- anticonvulsants (used to treat seizure disorders)

- antiretrovirals (used to treat human immunodeficiency virus)

- antineoplastics (used to treat cancer)

CMS allows plans to add medications and make other positive changes to their formulary throughout the year but restricts medication removal and other negative changes until the following January. This restriction protects patients from losing coverage for their prescriptions during the time when they cannot switch to a different Part D plan. Marketplace removal, safety concerns, and the availability of a new generic are examples of situations when CMS would allow removal of a medication from a Part D formulary during the year.

Part D plans must provide patients with ongoing access to their formulary information. Most Part D plans post formularies online and only provide paper copies upon request. Patients can also see the formulary status for their specific medications when comparing Part D plans using the MPF website.

COVERAGE DETERMINATIONS AND APPEALS

Patients and pharmacy personnel commonly generalize the term “prior authorization” to describe any situation that requires insurance approval before insurance covers a prescription. Under Medicare Part D, this is known as the coverage determination process. Part D patients may use the coverage determination process to request approval for a non-formulary medication or a formulary medication with restrictions.

Who hasn’t been frustrated after contacting a prescriber to change a non-formulary prescription to a formulary medication, only to have the formulary medication require prior authorization? Part D plans usually include messaging within rejected claims to help determine which type of coverage determination is needed. When faced with a prescription rejection, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who understand the nuances of the coverage determination process are equipped to advise their Part D patients on the best course of action.

Several specific types of coverage determinations are available and each type of coverage determination has specific criteria for approval.16,17 Table 3 provides a summary of coverage determination types, their uses, and the information required for approval.

Table 3. Types of Coverage Determinations and Their Uses16,17

| Medication Status | Coverage Determination | Requirements for Approval |

| On the formulary, but dosing regimen requires more than the formulary allowance or requires tablet splitting | Quantity Limit Exception | The quantity allowed by the plan’s formulary is not effective in treating the patient’s condition or requires tablet-splitting to achieve the prescribed dosing regimen. |

| On the formulary with step therapy restrictions | Step Therapy Exception

|

The patient tried the step medication and either did not achieve therapeutic effect or experienced an adverse outcome. |

| Step Therapy | The patient is likely to experience an adverse outcome if they must first try the step medication. | |

| On the formulary with prior authorization or “hard” DUR restrictions | Prior Authorization

|

The patient meets the Part D plan’s specific criteria for the prescribed medication. |

| On the formulary with a “soft” DUR restriction | None | DUR “soft edits” may require dispensing pharmacists to contact prescribers and obtain clinical information, but do not require a coverage determination. |

| Sometimes by Medicare Part B | Prior Authorization | Why the patient’s situation warrants coverage under Part D for the prescribed medication. |

| On the formulary, but the patient cannot afford the copay/coinsurance | Tier Exception | The required number† of lower tier drugs for the same condition are less effective or likely to result in an adverse outcome.

Not available for specialty or non-formulary medications and cannot provide a brand name medication at the generic cost. |

| Not on the formulary | Non-formulary Exception

|

The required number† of formulary alternative medication(s) were ineffective or likely to result in an adverse outcome. |

†Patients should consult their specific plan information to find out how many alternatives are required for tier or non-formulary exceptions.

Part D plans will only approve a coverage determination request if the product is medically necessary and if the information submitted by the prescriber meets the plan’s criteria. Prescribers may submit information over the phone, by fax, or by mail. Most Part D plans also have an electronic portal to accept information from prescribers. Dispensing pharmacists are only permitted to supply information in place of the prescriber under limited circumstances, such as prior authorizations to determine Part B versus Part D coverage.

Approval and Denial Parameters

For exception requests that meet approval criteria, CMS requires Part D plans to maintain the approval at least through the end of the year. Part D plans may approve prior authorizations for a shorter time only if clinically appropriate and approved by CMS as part of the annual formulary approval process.

Part D plans will deny requests with incomplete information and requests that do not meet approval criteria. Part D plans will also deny any type of coverage determination if the medication is being used for a non-medically accepted indication. Medically accepted indications are uses approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration or listed in one of the references that CMS defines as approved compendia10:

- American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information

- DRUGDEX Information System

- Peer-reviewed medical literature (only allowed for biologics and anti-cancer chemotherapy medications)

Common examples of medications prescribed for non-medically accepted indications include the use of fentanyl lollipops/lozenges for non-cancer pain and hydroxychloroquine for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Federal and state laws may allow prescriptions for non-medically accepted indications, but patients cannot use their Part D coverage to pay for them. Part D plans must block medication coverage if the determination process reveals a non-medically accepted indication, even for previously covered medications, quantities less than the predetermined limit, and any tier cost after a tier exception request.10 Pharmacists are not required to confirm medically accepted indications before dispensing prescriptions because CMS considers this a plan responsibility. As a result, Part D plans will often reject claims and require a prior authorization for medications commonly prescribed for non-medically accepted indications. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can assist patients and prescribers by communicating rejected claim information and explaining the CMS requirement for medically accepted indications. 10

In addition to medications covered under Part A or B, CMS specifically excludes certain types of medications from Part D coverage10:

- Products used for weight loss or weight gain

- Fertility medications

- Cosmetic and hair growth products

- Treatments for the symptomatic relief of cough and colds

- Non-prescription medications

- Prescription vitamins, except prenatal and fluoride products

- Erectile dysfunction treatments

Bulk powders and inert excipients used for compounded prescriptions are also excluded from Part D coverage. Compounds may contain other ingredients that are covered with or without restrictions under Part D. When pharmacies bill some of a compound’s ingredients to Part D, CMS prohibits them from charging patients for the non-Part D portion.10

Patients cannot obtain Part D coverage for excluded medications using the coverage determination process. Employers may cover some of these medications and manufacturer coupons or prescription discount cards may help make these products more affordable for individuals without employer coverage.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Generic sildenafil is prescribed for both erectile dysfunction (excluded from Part D coverage) and pulmonary hypertension (eligible for Part D coverage). Can a dispensing pharmacist distinguish between the two to bill Part D for the appropriate product?

Part D plans may dismiss requests that are inappropriate, unnecessary, or filed incorrectly. CMS requires Part D plans to provide written notification and a reason for the dismissal to the patient and prescriber. 17

If the patient or prescriber decides that a request is unnecessary, they can withdraw the request before a decision is issued. Withdrawing a request does not prevent the patient or prescriber from submitting a later request for the same medication.17

When a Part D plan denies a coverage determination, CMS requires them to send the specific reason(s) for the denial to the patient and the prescriber. Part D plans may choose to also send a copy of this information to the dispensing pharmacy.17 Depending on the reason for the denial, the patient or prescriber may choose to appeal the Part D plan’s decision.

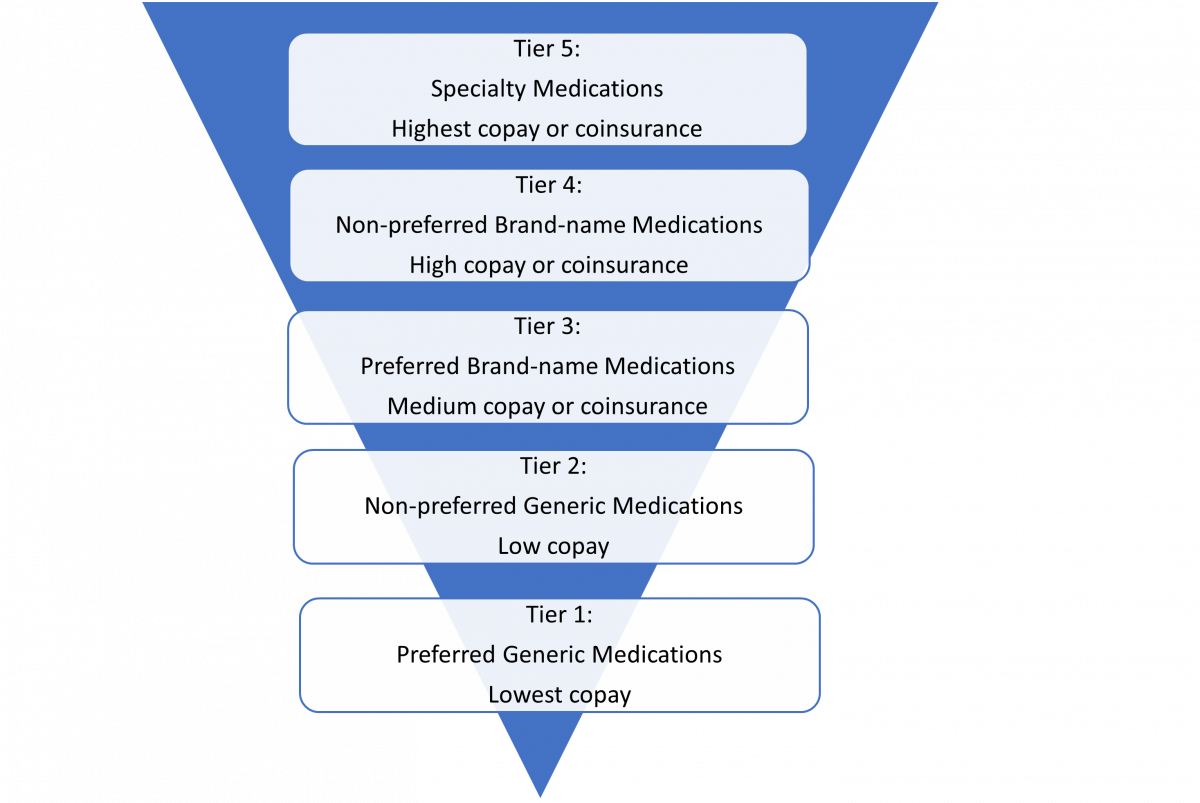

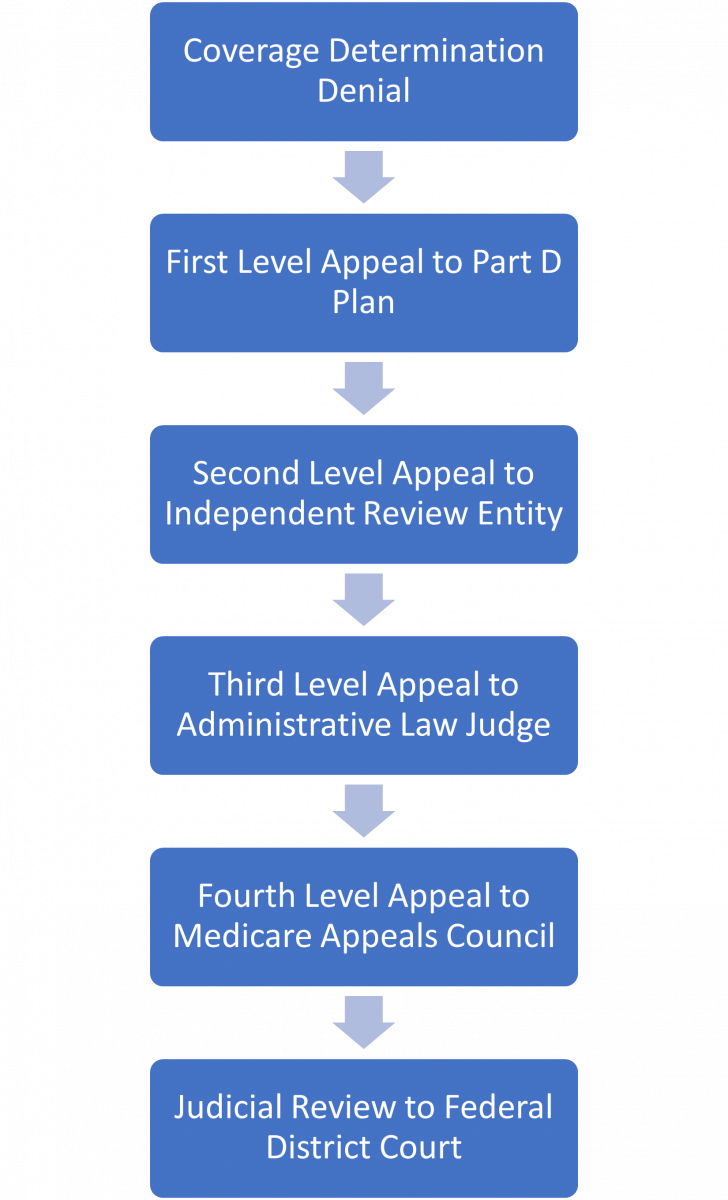

Appeal requests must be within 60 days of the denial, unless good cause is established for missing the 60-day deadline. If the Part D plan denies the appeal, beneficiaries have up to four additional opportunities to appeal through entities outside of their Part D plan. After the second level, higher levels of appeal are only available if the drug cost meets a specific threshold set by CMS.18 Figure 3 outlines the five levels of appeal available to Part D patients.

A patient or prescriber can request a re-opening instead of the next level appeal if they feel that a coverage determination or appeal decision is in error. Part D plans may also initiate a re-opening if they identify a decision error.

Direct Member Reimbursements

Patients who pay for a covered Part D prescription without using their Part D Insurance may be eligible for reimbursement from their Part D plan through a process called Direct Member Reimbursement (DMR). To qualify for DMR, the prescription must meet the Part D plan’s coverage requirements and not be covered by any other type of insurance or discount card. Prescriptions obtained at an OON pharmacy must meet the Part D plan’s OON rules to qualify for reimbursement.19

Pharmacies should submit Part D prescriptions to the patient’s Part D plan whenever possible because a DMR reimbursement may not result in a full refund of the cash price.

Timeframes

Part D plans must offer both standard and expedited timeframes for coverage determination and appeal requests (listed in Table 4). Expedited requests are available when the standard timeframe could result in a significant adverse outcome. DMR requests do not qualify for expedited timeframes because the patient has already received the medication.17

Table 4. Plan Timeframes for Medicare Part D Requests16

| Request Level | Request Urgency | Request Type | Required Timeframe |

| Initial Coverage Determination | Standard | Quantity Limit Exception

Step Therapy Exception Tier Exception Non-Formulary Exception |

72 hours from supporting statement but no longer than 14 days from request received

|

| Initial Coverage Determination | Expedited | Quantity Limit Exception

Step Therapy Exception Tier Exception Non-Formulary Exception |

24 hours from supporting statement but no longer than 14 days from request received

|

| Initial Coverage Determination | Standard | Prior Authorization

Step Therapy (non-exception) |

72 hours from request received |

| Initial Coverage Determination | Expedited | Prior Authorization

Step Therapy (non-exception) |

24 hours from request received |

| Initial Coverage Determination | N/A | Direct Member Reimbursement | 14 days from request received |

| First Level Appeal | Standard | Quantity Limit Exception

Step Therapy Exception Tier Exception Non-Formulary Exception Prior Authorization |

7 days from request received |

| First Level Appeal | Expedited | Quantity Limit Exception

Step Therapy Exception Tier Exception Non-Formulary Exception Prior Authorization |

72 hours from request received |

| First Level Appeal | N/A | Direct Member Reimbursement | Notification of Decision: 14 days from request received

Payment (if approved): 30 days from request received |

Part D plans may automatically apply the expedited timeframe if the clinical information submitted for the coverage determination indicates that waiting may harm the patient’s health. Alternatively, Part D plans may downgrade an expedited request if they determine that the patient’s health will not be harmed by using the standard timeframe. CMS requires Part D plans to notify the patient if a request is downgraded from expedited to standard.17

All Part D timeframes are based on calendar hours/days and include weekends and holidays. Timeframes start as soon as the Part D plan receives a non-exception coverage determination or any type of valid appeal request, regardless of how much clinical information is included with the request. For exception requests, the timeframe starts as soon as the Part D plan receives clinical information from the prescriber to support the request (known as the prescriber’s supporting statement). When a supporting statement is missing from an exception request, CMS allows up to 14 days for plans to obtain it.17 The following examples demonstrate Part D timeframes over weekends and holidays:

- A patient requests a standard prior authorization on Friday afternoon, December 23. The prescriber’s office is closed for the three-day holiday weekend. The plan must deny the request in 72 hours (on Monday afternoon), even though the prescriber’s office was not available to provide information during that timeframe.

- A different patient requests a standard non-formulary exception the same day. Their prescriber’s office is also closed for the three-day holiday weekend but contacts the plan with the supporting information on Tuesday morning. Since this is an exception request, 72 hour timeframe starts on Tuesday morning and the plan has until Friday morning to complete the request.

When clinical information is incomplete, CMS requires that Part D plans make reasonable efforts to contact the prescriber and obtain the missing information. Once the timeframe has started, making outreach attempts and waiting for additional information does not extend the request timeframe. The Part D plan will deny the request if they do not receive sufficient clinical information by the end of the allotted timeframe.17

PAUSE AND PONDER: It’s late Friday afternoon and your patient is anxious to request a prior authorization for her medication. The physician’s office is closed for the weekend. Could requesting an expedited coverage determination at this point cause more of a delay?

When a Part D plan does not process a request within the required timeframe, they must send the request to the IRE as an “auto-forward.” This is the same IRE that processes Part D second-level appeals. Part D plans must notify patients in the event of an auto-forward. CMS monitors Part D plans’ timeliness and issues penalties for excessive numbers of auto-forwards.

How to Submit Requests

CMS requires that Part D plans accept coverage determination requests via phone, fax, or mail. For appeals, plans must accept both standard and expedited requests via fax or mail. Verbal requests by phone are required for expedited appeals but optional for standard appeals.17 Many plans also choose to accept electronic requests via an online portal.

Patients should follow the instructions from their specific Part D plan for requesting a DMR. Part D plans usually require hard copies of payment receipts, so most patients file DMR requests by mail.

CMS does not permit Part D plans to require a specific form to submit a coverage determination, appeal, or DMR request.17 Although optional, using a form provided by the plan usually streamlines the process and reduces the risk of submitting incomplete information.

CMS does not allow dispensing pharmacists or pharmacy technicians to request a Part D coverage determination or appeal on behalf of the patient. Only the patient, the patient’s appointed representative, the prescriber, or the prescriber’s staff can request a coverage determination or appeal. Only patients or their appointed representative can request a DMR.17

The handout entitled “Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage and Your Rights” that dispensing pharmacies supply to patients when prescriptions cannot be filled under their Part D plan provides additional instructions for submitting requests.17,20

CONCLUSION

Medicare patients have many choices available for their prescription drug coverage. CMS requires that all Part D plans conform to a set of common standards while allowing specific plans to offer a wide range of benefit options.

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians with a basic understanding of Part D coverage options, patient costs, formulary structure, and the coverage determination and appeals process can help patients maximize the benefit from their Part D plan. Although CMS does not allow them to initiate coverage determinations and appeals, pharmacy personnel can advise Part D patients and their physicians on the most effective next steps when faced with a non-covered prescription.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

All “Prior Authorizations” are Not Created Equal: A Guide to Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage

Pharmacists Post-test

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

1. Describe the different types of prescription drug coverage available to Medicare patients.

2. Explain the patient costs associated with Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage.

3. Demonstrate use of a patient’s Medicare Part D formulary to determine the appropriate type of coverage determination.

4. Identify prescriptions that Medicare Part D does not cover.

1. Which of the following is the correct description for the type of Medicare coverage?

A. Medicare Part A: Covers outpatient and home health care, preventative services, and durable medical equipment.

B. Medicare Part B: Offered by private insurance companies for prescription drug coverage.

C. Medicare Part C: Offered by private insurance companies to provide Part A and Part B coverage.

2. What is an appropriate combination of coverage?

A. Medicare Part A + Medicare Part B + Medicare Part D

B. Medicare Part A + Medicare Part B + MAPD

C. Employer Coverage + Medigap + MAPD

3. A patient who is turning 65 next month asks you about delaying Part D coverage because she only takes two prescriptions that are very low cost using a prescription discount card. What is the possible risk of this approach when she eventually signs up for Part D coverage at a later date?

A. She may pay higher monthly premiums due to the coverage gap.

B. She may pay higher annual deductibles due to the late enrollment penalty.

C. She may pay higher monthly premiums due to the late enrollment penalty.

4. It’s January and a patient who paid a $10 copay for his prescription last month now has to pay 100% of the cost. What is the most likely explanation?

A. He is paying the annual deductible

B. He is in the coverage gap

C. His Part D plan doesn’t cover his medication

5. A patient who takes several expensive medications experiences a sharp increase in her out-of-pocket costs around midyear. What is the most likely explanation?

A. She has entered the deductible phase

B. She has entered the coverage gap phase

C. She has entered the catastrophic coverage phase

6. A patient’s Part D Plan is rejecting a prescription for apixaban. You locate its formulary online and find that dabigatran is listed, but not apixaban. What type of coverage determination does this patient need from this Part D Plan?

A. Step Therapy

B. Non-formulary

C. Prior Authorization

7. A patient’s Part D Plans is rejecting a prescription for alirocumab. You locate the formulary online and find that alirocumab is on the formulary but is not covered unless simvastatin has been tried first. What type of coverage determination does this patient need from this Part D Plan?

A. Step Therapy

B. Prior Authorization

C. Tier Exception

8. A Part D patient is struggling to afford his medication, even after the Part D Plan approved a non-formulary exception. What is their best option for lowering costs?

A. Talk to the prescriber about switching to an alternative on a lower formulary tier.

B. Ask their Part D Plan for a tier exception.

C. Find a manufacturer discount coupon to cover their Part D copay.

9. A Part D patient presents a prescription for a highly advertised diabetic medication and confides in you that she is not diabetic but hoping the medication will help with weight loss. Her Part D Plan requires prior authorization to establish medically accepted indication. What coverage option is available to them?

A. Part D after prior authorization approval

B. Manufacturer discount program

C. Medicare Advantage

10. A Medicare Part D Plan is rejecting claims for your patient’s diabetic test strips and lancets. What do you recommend as the next course of action?

A. Call the Part D Plan and request a coverage determination.

B. Pay out of pocket and ask the Part D Plan for direct member reimbursement.

C. Compile the documentation required to submit the claims to Part B.

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

All “Prior Authorizations” are Not Created Equal: A Guide to Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage

Pharmacy Technician Post-test

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

1. Describe the different types of prescription drug coverage available to Medicare patients.

2. Explain the patient costs associated with Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage.

3. Identify the types of coverage determinations available for Medicare Part D prescriptions.

4. Outline the timeframes involved in Medicare Part D coverage determination and appeal decisions.

1. Which of the following is the correct description for the type of Medicare coverage?

A. Medicare Part A: Covers outpatient and home health care, preventative services, and durable medical equipment.

B. Medicare Part B: Offered by private insurance companies for prescription drug coverage.

C. Medicare Part C: Offered by private insurance companies to replace Part A and Part B coverage.

2. What is an appropriate combination of coverage?

A. Medicare Part A + Medicare Part B + Medicare Part D

B. Medicare Part A + Medicare Part B + MAPD

C. Employer Coverage + MAPD

3. A patient who is turning 65 next month asks you about delaying Part D coverage because she only takes two prescriptions that are very low cost using a prescription discount card. What is the possible risk of this approach when she eventually signs up for Part D coverage at a later date?

A. She may pay higher monthly premiums due to the coverage gap.

B. She may pay higher annual deductibles due to the late enrollment penalty.

C. She may pay higher monthly premiums due to the late enrollment penalty.

4. It’s January and a patient who paid a $10 copay for his prescription last month now has to pay 100% of the cost. What is the most likely explanation?

A. He is paying the annual deductible

B. He is in the coverage gap

C. His Part D plan doesn’t cover his medication

5. A patient who takes several expensive medications experiences a sharp increase in her out-of-pocket costs around midyear. What is the most likely explanation?

A. She has entered the deductible phase.

B. She has entered the coverage gap phase.

C. She has entered the catastrophic coverage phase.

6. Which of the following combinations of coverage determinations may be required for a single prescription?

A. Non-formulary + Quantity Limit

B. Quantity Limit + Prior Authorization

C. Tier Exception + Non-formulary

7. Which type of reject requires a Part D coverage determination?

A. Non-formulary

B. Refill too soon

C. DUR soft edit

8. Which of the following is the correct description for a type of coverage determination under Medicare Part D?

A. Non-formulary exceptions: Used to request larger quantities of a medication

B. Tier Exceptions: Used to request a lower copay for a medication

C. Prior Authorization: Used to request a non-formulary medication

9. A patient called her Part D plan yesterday morning to request an urgent appeal for their medication. This afternoon, she has not received a response and the claim is still rejecting. How much longer might she have to wait for a response?

A. The appeal is already out of timeframe because it has been longer than 24 hours

B. 6 more days, for a total of 7 days

C. 2 more days, for a total of 3 days

10. You are working on a prescription that the Part D Plan is rejecting due to a quantity limit. The patient is not out of medication, so you advise him to call and ask for a standard quantity limit exception. How long should the patient expect to wait for the Part D Plan to make a decision?

A. 24 hours after the patient calls their Part D Plan to request the coverage determination

B. 24 hours after their prescriber provides clinical information to the Part D Plan

C. 72 hours after their prescriber provides clinical information to the Part D Plan

References

Full List of References

References

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Enrollment Dashboard. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://data.cms.gov/tools/medicare-enrollment-dashboard

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & You Handbook. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/medicare-and-you

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Help with Drug Costs. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/basics/costs/help/drug-costs

4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Explore Your Medicare Coverage Options. Accessed September 13, 2023. www.medicare.gov/plan-compare

5. RelayHealth. Medicare Eligibility Verification Transaction. Accessed December 28, 2023. https://medifacd.mckesson.com/e1/

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual Chapter 5: Benefits and Beneficiary Protections. September 20, 2011. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/prescription-drug-coverage/prescriptiondrugcovcontra/downloads/memopdbmanualchapter5_093011.pdf

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Costs in the Coverage Gap. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap

8. Kaiser Family Foundation. Changes to Medicare Part D in 2024 and 2025 Under the Inflation Reduction Act and How Enrollees Will Benefit. Accessed December 27, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/changes-to-medicare-part-d-in-2024-and-2025-under-the-inflation-reduction-act-and-how-enrollees-will-benefit

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2024 Medicare Advantage (MA) Capitation Rates and Part C and Part D Payment Policies. March 31, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2024-announcement-pdf.pdf

10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual Chapter 6 – Part D Drugs and Formulary Requirements. January 15, 2026. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/prescription-drug-coverage/prescriptiondrugcovcontra/downloads/part-d-benefits-manual-chapter-6.pdf

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual Chapter 12 – Employer/Union Sponsored Group Health plans. November 7, 2008. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/transmittals/downloads/dwnlds/r6pdbpdfpdf

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Learn How Medigap Works. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/health-drug-plans/medigap/basics/how-medigap-works

13. Office of Inspector General. Special Advisory Bulletin, Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Copayment Coupons. September 2014. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/special-advisory-bulletins/878/SAB_Copayment_Coupons.pdf

14. Dr Christina Polomoff discusses the complex world of medication discount cards. Am J Manag Care. April 13, 2021. Accessed September 5, 2023. www.ajmc.com/view/dr-christina-polomoff-discusses-the-complex-world-of-medication-discount-cards

15. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What Medicare Pat D plans Cover. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/what-medicare-part-d-drug-plans-cover

16. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Final Contract Year (CY) 2024 Part D Bidding Instructions. April 4, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/final-cy-2024-part-d-bidding-instructions.pdf

17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Parts C&D Enrollee Grievances, Organization/Coverage Determinations, and Appeals Guidance. August 3, 2022. Accessed September 10, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/appeals-and-grievances/mmcag/downloads/parts-c-and-d-enrollee-grievances-organization-coverage-determinations-and-appeals-guidance.pdf

18. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Appeals. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/11525-Medicare-Appeals.pdf

19. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual Chapter 14 – Coordination of Benefits. September 17, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Chapter-14-Coordination-of-Benefits-v09-14-2018.pdf

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage and Your Rights. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/outreach/partnerships/downloads/yourrightsfactsheet.pdf