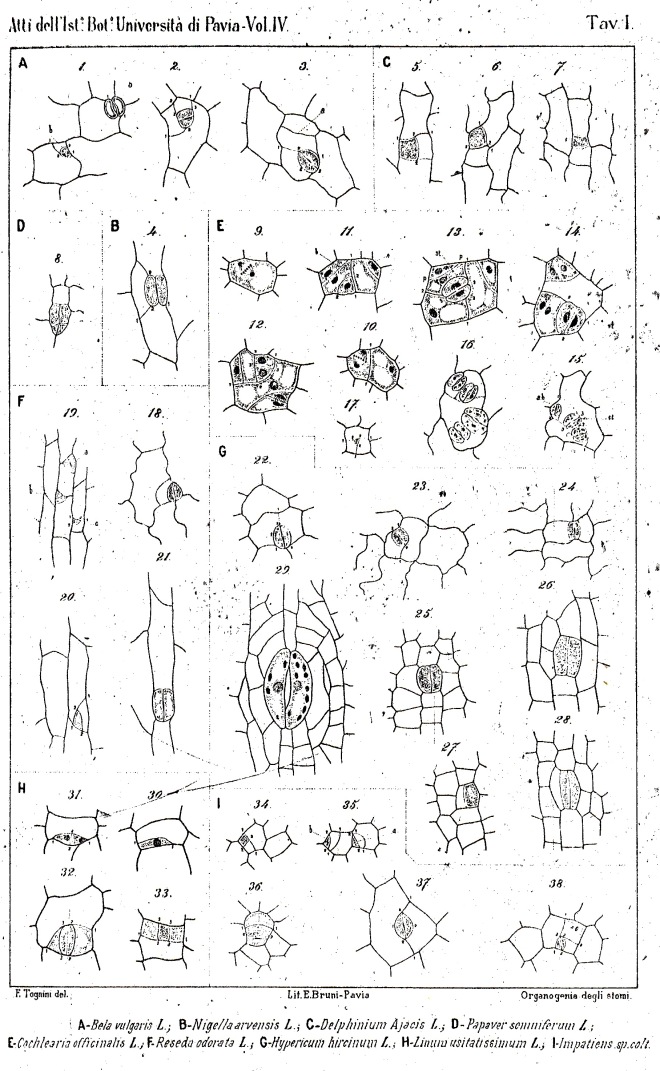

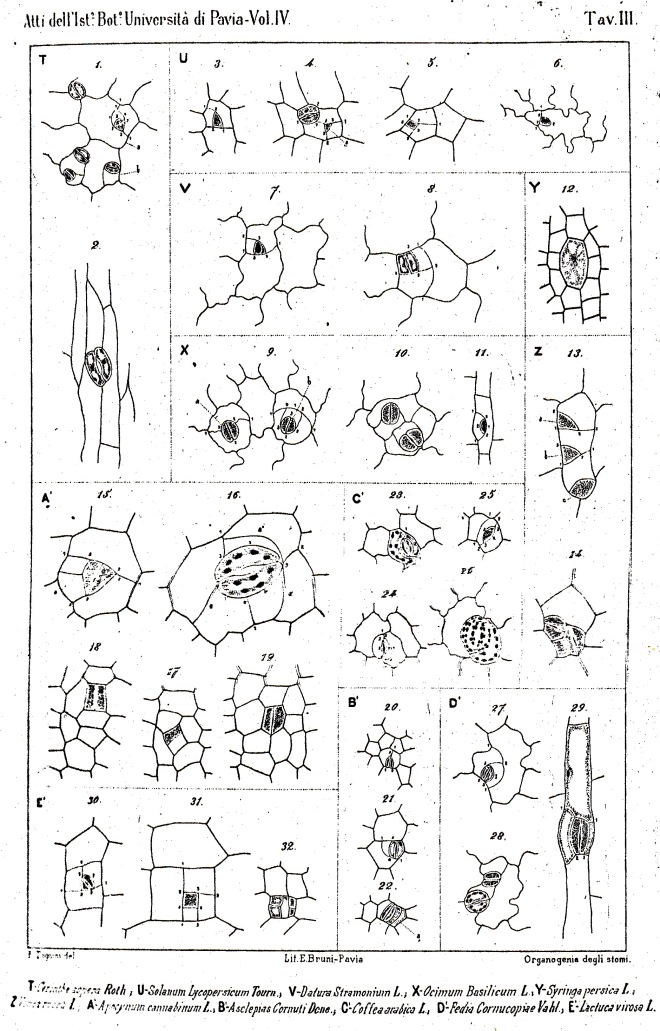

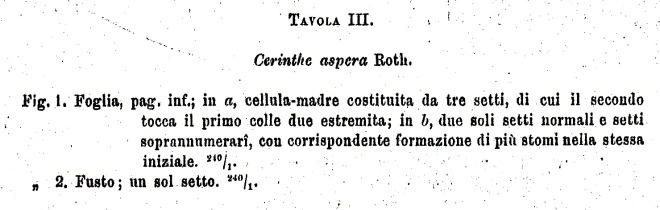

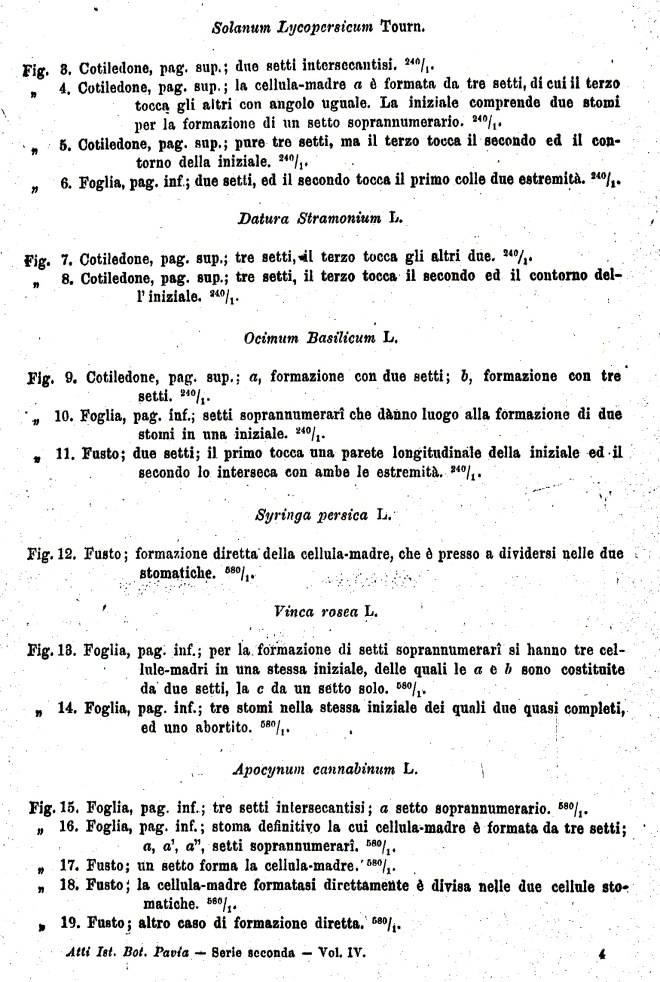

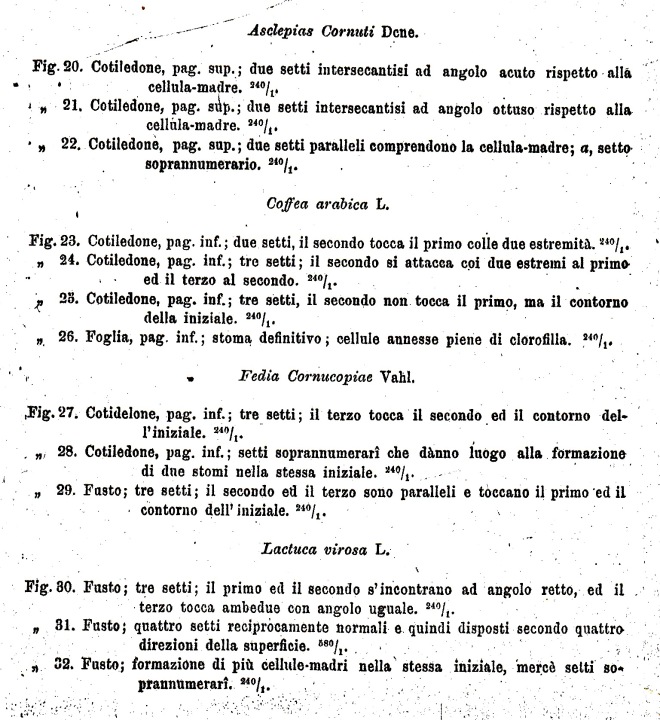

Ontogenetic basis for classification of stomatal complexes – a reapproach

by Timonin A. C. (1995)

A. C. Timonin, Department of Higher Plants Morphology and Systematics, Biological Faculty, M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Vorobyevy Gory, 119899, Moscow, Russia.

in Flora 190: 189-195 – https://doi.org/10.1016/S0367-2530(17)30650-3

Summary

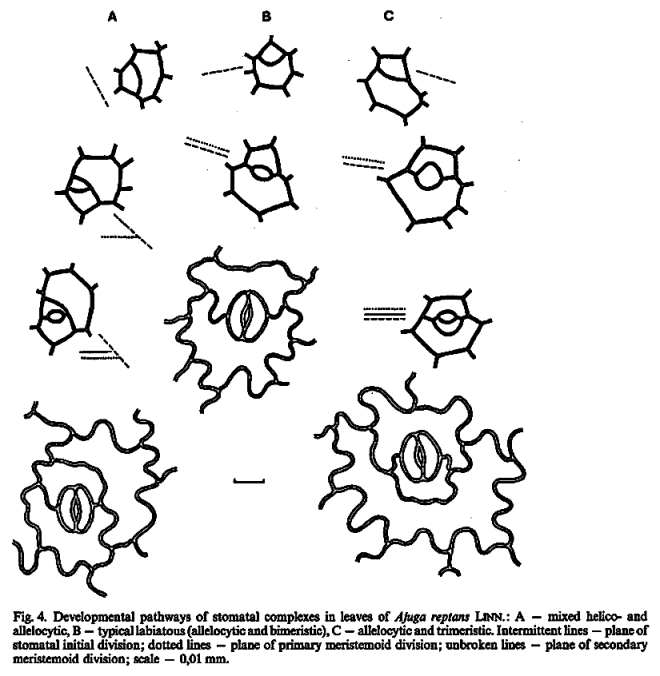

The majority of existing ontogenetic classifications of stomatal complexes is considered to be, in fact, a mixture of structural and ontogenetic ones.

Purely ontogenetic classifications should be based on only three characters:

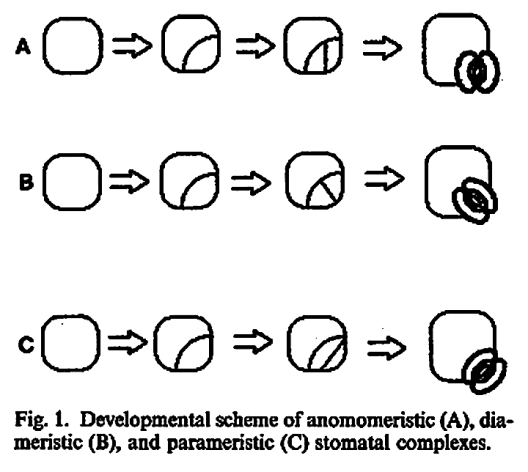

a) orientation of guard cells’ mother cell division in relation to the plane of the preceding cell division ;

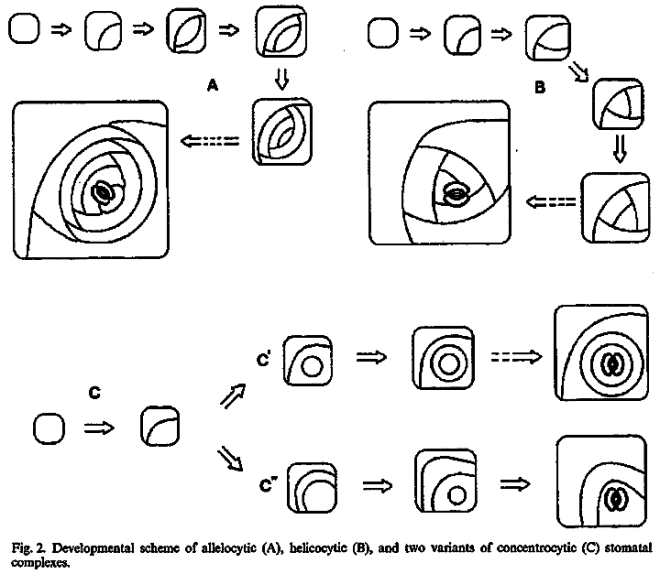

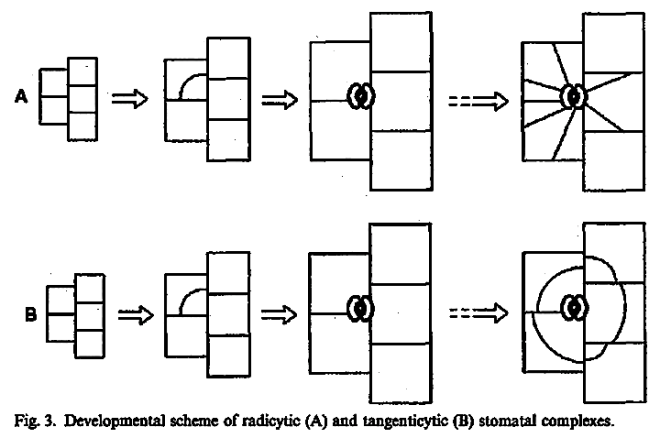

b) orientation of the divisions of cells other than guard cells’ mother cell and

c) number of cell divisions leading to mature stomatal complex formation.

This method would result in three independent and reciprocally supplementary stomatal classifications. The first one consists of only PAYNE’S anomo-, dia-, and parameristic types. The second one contains both PAYNE’S allelo- and helicocytic types and new concentro-, radi-, and tangenticytic stomatal types. For the third classification, monomeristic and bimeristic types, and so forth, are proposed.

Two neglected unnamed STRASBURGER’S and PRANTL’S stomatal types are reintroduced as initial, resp. terminal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.