Inocybe reisneri Velen. 1920 is another addition to the list of Inocybe section Rimosae from Novosibirsk Akademgorodok. Last August these fibercaps fruited all over Akademgorodok, always near birch (Betula pendula), preferring shaded lawns bordering forest patches, and sides of busy forest trails (Akademgorodok is all about forest trails).Once again, I failed to take decent in situ photos, probably because these fungi were so abundant I kept hoping to find a better-looking group, and fell victim to perfectionism multiplied by absent-mindedness.

They stand out of the Inocybe crowd thanks to their elegant fruitbodies with subbulbous stipe, shiny silky caps with scattered patches of white velipellis, violet tinge in the upper part of the stipe and in lamellae, and peculiar smell, which I could only describe as fresh and reminiscent of shieldbugs at the same time. The smell was what prevented me from identifying the species quickly, because it required a two-step move: the thing is, the closest species in Funga Nordica and in Kuyper’s 1986 monograph is Inocybe quietiodor, which is very, very similar (apart from the violet tinge), but a key feature in identifying it is its odor, which is said to be the same as “that of Lactarius quietus“. Apparently, Lactarius quietus is a very common milk cap in Europe, and every decent mycologist should know the smell very well. The problem is, it’s mycorrhizal with oak, and there are only a few planted oak trees in Akademgorodok, and no Lactarius quietus under them (at least yet). We had to google up what Lactarius quietus smells like, and learned that it smelled of “shieldbugs and wet laundry“. Bingo! But the violet tinge wasn’t mentioned in any of the sources.

Yesterday, having travelled for over a month and a half, a great book, an English translation of Stangl’s The Genus Inocybe in Bavaria (available from Summerfield Books), finally made it to Ugut (parcels sent to Russia often deserve their own versions of “The Incredible Journey”). I found our mystery species right away just by flipping through color plates, and it was Inocybe reisneri. A reminder of how important a good library is.

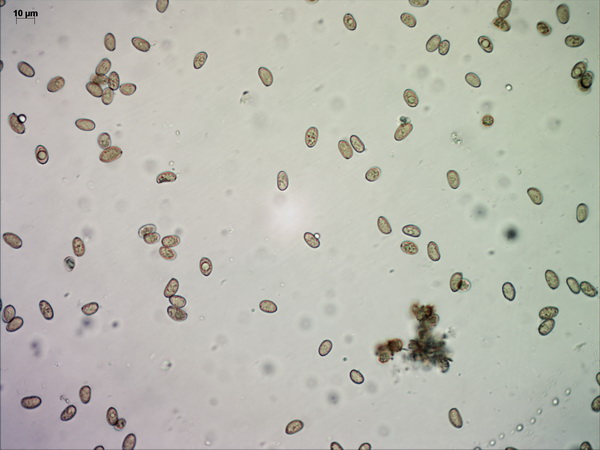

Spores measure (9.3-) 9.5 – 12.2 (-12.7) x 5.7 – 7.1 (-7.4), L = 9.88, W = 6.26, Q = 1.58 (n = 92), which makes them a bit larger than what’s given in Stangl’s description.

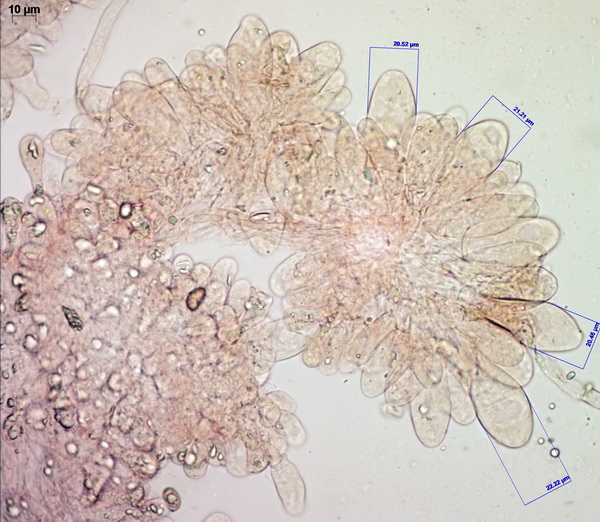

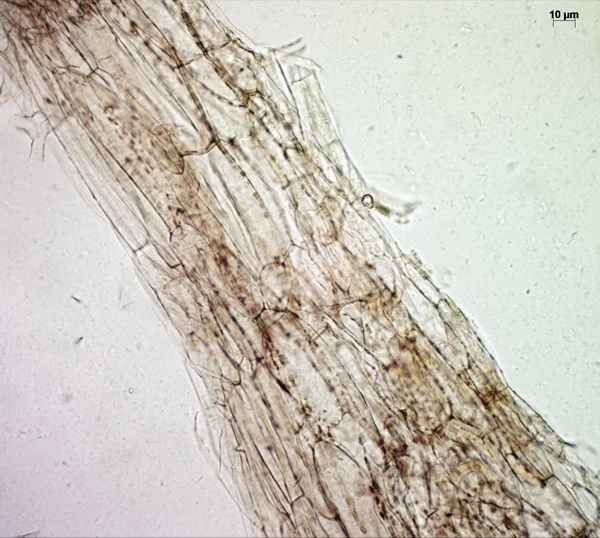

Cheilocystidia are mostly clavate (not very narrow, not very broad). Pileipellis is comprised of relatively thin, barely inflated hyphae with a delicate zebroid pattern of golden-brown pigment incrustation (there is intracellular pigment as well).

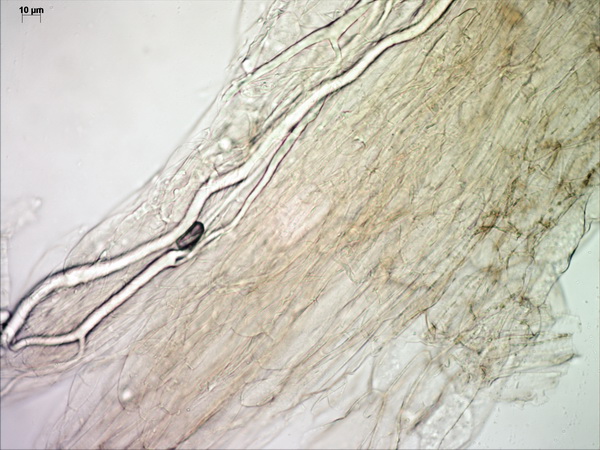

Above the pileipellis there is a layer of interwoven, thin, colorless, collapsed hyphae – the velipellis. There are quite a few branching, anastomosing refractive hyphae (also called vascular, or oleiferous hyphae) – as I’ve already remarked, the abundance of these hyphae in a fruitbody is probably linked to the intensity of its smell. The stipe surface is almost polished with just a few scattered small fibrils of velar hyphae with uninflated, cylindric terminal elements.