This is the story of a particular plant in a particular place. The plant is Aconogonon davisiae, a.k.a. Davis’ knotweed. Davis’ knotweed is a hardy, high-elevation herbaceous perennial of the central and northern Sierra Nevada, the Cascades, Klamath Mountains, and North Coast Range. Although it can occasionally be found as low as about 5,000 feet in elevation, it is most common above 7,000 feet, where it inhabits scree slopes, gravelly ridges, dry open flats, and open forests. A member of the Buckwheat Family (Polygonaceae), Davis’ knotweed, with its drab and unassuming flowers, is easily overlooked all summer long—but in the fall, it can provide spectacular displays.

While Davis’ knotweed has a very wide range, the particular place for this story is Ridge Lakes in Lassen Volcanic National Park. The lake is about 8,000 feet in elevation. This area is the headwaters for West Sulphur Creek.

In the Sierra Nevada, this lake would be surrounded by vertical granite walls. Since the volcanic rock at Lassen Volcanic National Park is much softer than granite, the lake is surrounded by steep scree slopes.

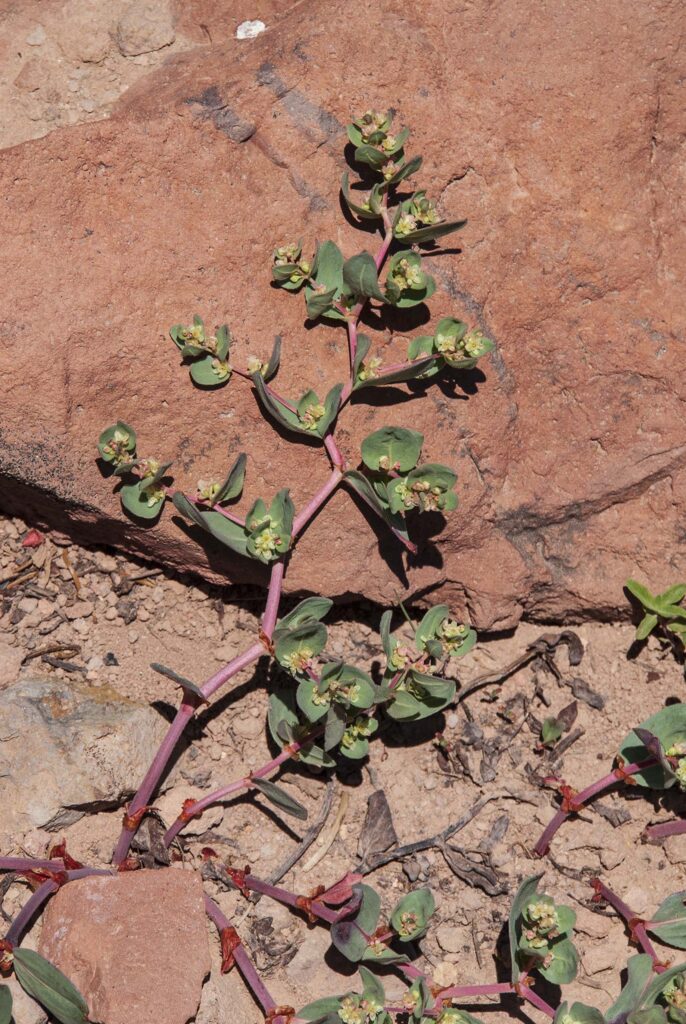

The star of the show, again, is Davis’ knotweed, Aconogonon davisiae.

Photo taken July 9, 2018.

This plant is interesting for many reasons. For one, it uses the “snow lily strategy” of pushing through the snow (or ice) ASAP in the spring. It relies on anthocyanin “antifreeze” to avoid damage to tender shoots from low nighttime temperatures or unexpected cold snaps. As a result, the first shoots to push up are deep red with a viscid, almost slimy, quality, which is very striking.

Also, this plant will actually begin growth underwater and remain there for weeks. I did not think that this was possible. I thought that aquatic plants required special adaptations to survive in the very low oxygen levels present in lakes. Davis’ knotweed is not an aquatic plant, but clearly it has a workaround.

Seemingly, Davis’ knotweed doesn’t grow out of the water. It waits until the lake level drops. Then it ramps up the concentration of chlorophyll in the leaves and continues its life cycle.

Davis’ knotweed starts early and ends early. Like most perennials in this area, it enters dormancy in a staggered fashion.

Like other subalpine perennials, the last step in dormancy is to withdraw water, leaving very dry leaves and stems.

In a realm where the trees are all conifers, any fall color must be provided by herbs and shrubs. Davis’ knotweed is the one of the largest contributors to fall color in this watershed.

This bright red-orange dormancy can be used to get to get a visual sense of the abundance of Davis’ knotweed in this watershed.

Photo taken September 9, 2020.

In one respect, early dormancy makes perfect sense. The steep slopes where Davis’ knotweed often thrives dry out early in the summer. Water is essential for growth and reproduction. This micro-environment favors early dormancy. What we have is a plant shaped by and in tune with its environment. However, other plants in this environment have obviously solved the water problem and are active and thriving. How does Davis’ knotweed remain competitive?

If we look at its abundance, early dormancy is clearly a winning strategy for Davis’ knotweed. The question is, how? The phenomenon pictured below gave me my first clue.

This might seem like an oddity, but an inspection downwind along the lake shore revealed that a great deal of Davis’ knotweed is being rolled. With the exception of mountain hemlock cones and needles and various cypselae (dry single-seeded fruits), this is the only material being transported across the lake to its edge.

Photo taken October 7, 2020.

My second clue was a stem that I found on the trail after a rainstorm. The stem had many empty receptacles, but two achenes were still attached at the second node. In essence, Davis’ knotweed uses the physical movement of broken stems as one mode of seed dispersal. This was surprising to me. It is not a tumbleweed. It is a very successful rollerweed.

Once this idea took root, other observations started to fall into place. When this plant goes into dormancy, the leaves fold up along the stem creating the roller shape and protecting the areas where achenes are located. Not always, but this happens regularly and is in sharp contrast to other successful plants in this area, like satin lupine.

For these stems to float, they must have a low density. To roll in the wind, they must be lightweight. I couldn’t measure the density, but their low weight is obvious. All you have to is pick up a piece. In fact, they are light enough to be blown uphill with ease.

Photo taken October 11, 2020.

Given their behavior moving across a lake, it is quite easy to imagine these fragments being easily moved by rainfall. They will float along and collect at the low spots where water naturally flows.

Whether fragments are moved by water or wind, they will tend to collect in any low spot.

In essence, Davis’ knotweed is using a variant of the “tumbleweed strategy.” I think of it as the “rollerweed strategy.” Its seeds are widely distributed without animal agency. However, this strategy only works before winter snows begin to accumulate. Snow literally freezes things in place. So, for this mode of dispersal in this habitat, early dormancy is more than ideal, it is essential. It gives Davis’ knotweed the competitive advantage that compensates for early dormancy. It maximizes the time that seeds have to be moved to new locations.

Let me end with an aside. I was attracted to Davis’ knotweed for artistic reasons long before I got interested in its life cycle. With time, I began to ask myself questions about how it could be so successful.

For the artist, Davis’ knotweed is just as compelling in the background as it is in the foreground. Below is a photo of western pasqueflower, Anemone occidentalis, with achenes still attached to the receptacle. It has a lovely reddish background courtesy of Davis’ knotweed. ~Greg Lockett