https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9gQHYJ0wYQ

Stretching out fifty miles north of London and Windsor Castle’s boundaries, Buckinghamshire became a hostile area toward castles during the middle ages. Long-abandoned Norman edifices include Buckingham Castle, Castlethorpe and Bolebec. Boarstall Tower is the only medieval stone castle which displays any above-ground evidence and, even so, what remains is the result of self-evident continual reconstruction. Most of the fortified manor is gone from sight, however. Apparently, the 1770s was a good year for castle demolishment in this county but the widely-believed assumption that there were never any castles built in Bucks County is plain false. In general, until the 21st century, the county has remained largely and charmingly undeveloped and it teems with long-abandoned motte and bailey sites. Milton Keynes in north Buckinghamshire is a burgeoning metropolis amidst the blissful hush. Oxfordshire’s Chiltern Hills stretch into Buckinghamshire along the Thames Valley in the southwest, which is mostly countryside along with pretty villages and small market towns. Both counties seem to share Henley-on-Thames although Berkshire also lays claim. Buckinghamshire’s stellar architecture is at Stowe which is three miles northwest of Buckingham. This grandiose marvel is so extensive that it will soon have its own entry on this blog along with several other magnificent stately and grand homes such as Waddesdon and Cliveden. The following is what I have uncovered through dogged determination and downright digging to find what can get buried with time…

The origin of Buckingham commenced in the 7th century with an Anglo-Saxon leader by the name of Bucca. A settlement appeared at the top of a loop in the River Ouse which is present at the current location of the Hunter Street campus for University of Buckingham. Saxons and Danes struggled for power in the area for a few hundred years until King Edward the Elder encamped an army close by (ca. 914) where Buckingham Castle eventually was erected after the conquest. According to the Burgal Hidage, King Alfred had set up a system of forts over the entire West Saxon kingdom and Edward had come to restore what had already been there for a generation. In doing so, he ousted Danish Vikings who had tried to take over the area known, at the time, as southern Mercia.

The origin of Buckingham commenced in the 7th century with an Anglo-Saxon leader by the name of Bucca. A settlement appeared at the top of a loop in the River Ouse which is present at the current location of the Hunter Street campus for University of Buckingham. Saxons and Danes struggled for power in the area for a few hundred years until King Edward the Elder encamped an army close by (ca. 914) where Buckingham Castle eventually was erected after the conquest. According to the Burgal Hidage, King Alfred had set up a system of forts over the entire West Saxon kingdom and Edward had come to restore what had already been there for a generation. In doing so, he ousted Danish Vikings who had tried to take over the area known, at the time, as southern Mercia.

Today you won’t find a trace of Buckingham Castle even though it once sat on a hill on the north side of the River Ouse, south of the grandiloquent Stowe House and Gardens. It was replaced with a parish church (St. Peter and Paul Church) which can be seen from every direction within and outside the town. Buckingham is still small, as market towns in England often are but you’ll find almost no medieval buildings although it still had them up until 1725 when a fire gutted the town. Many of the main streets were destroyed including Castle Street, Castle Hill and the north side of Market Hill. Because of this you’ll discover the town’s architecture is primarily 18th century Georgian and rebuilding after the fire took the better part of a century. By the time the castle was in the possession of the Giffard family it had already been dismantled! The motte remained, apparently, until 1777 when it was finally leveled for the churchyard. The walls which surround the churchyard green and on the end of Castle Street originally surrounded the castle. Portions of these walls were unearthed in 1877- a hundred years later! Even so, only the documentary sources of the castle’s existence from 1154-64 support the claims that the castle ever stood there! It was founded early enough to receive a prisoner in 1071 who was Herward the Wake (the leader of the Anglo-Saxon resistance against the Norman invasion) so it was built some time after the Conquest and was mentioned in the Domesday book by 1086.

Today you won’t find a trace of Buckingham Castle even though it once sat on a hill on the north side of the River Ouse, south of the grandiloquent Stowe House and Gardens. It was replaced with a parish church (St. Peter and Paul Church) which can be seen from every direction within and outside the town. Buckingham is still small, as market towns in England often are but you’ll find almost no medieval buildings although it still had them up until 1725 when a fire gutted the town. Many of the main streets were destroyed including Castle Street, Castle Hill and the north side of Market Hill. Because of this you’ll discover the town’s architecture is primarily 18th century Georgian and rebuilding after the fire took the better part of a century. By the time the castle was in the possession of the Giffard family it had already been dismantled! The motte remained, apparently, until 1777 when it was finally leveled for the churchyard. The walls which surround the churchyard green and on the end of Castle Street originally surrounded the castle. Portions of these walls were unearthed in 1877- a hundred years later! Even so, only the documentary sources of the castle’s existence from 1154-64 support the claims that the castle ever stood there! It was founded early enough to receive a prisoner in 1071 who was Herward the Wake (the leader of the Anglo-Saxon resistance against the Norman invasion) so it was built some time after the Conquest and was mentioned in the Domesday book by 1086.

Accidental 19th century discoveries show that this castle was built in stone at some point but probably not by the original holders- William de Braose and subsequently his son Giles de Braose. The latter mentioned died in 1305 after the demolishment of the castle and documents stated it to be worth nothing by that time. Apparently, it laid mostly in ruins but was still in partial use up until the late 15th century when the remains were leased to Thomas Smythe and the account books for the castle had a list of expenses for parts of the building still in operation. Buckingham’s ruins still had a ‘garret’ (perhaps the remains of a tower?), cook’s chamber and stables in 1473. Non-deliberate excavations in the ensuing centuries were revelatory but evidence has presented itself several times- basically, every time someone digs around the area- and especially the oval keep mound beneath the churchyard of Saints Peter and Paul. Mostly the finds are of the masonry of the ancient castle.

Accidental 19th century discoveries show that this castle was built in stone at some point but probably not by the original holders- William de Braose and subsequently his son Giles de Braose. The latter mentioned died in 1305 after the demolishment of the castle and documents stated it to be worth nothing by that time. Apparently, it laid mostly in ruins but was still in partial use up until the late 15th century when the remains were leased to Thomas Smythe and the account books for the castle had a list of expenses for parts of the building still in operation. Buckingham’s ruins still had a ‘garret’ (perhaps the remains of a tower?), cook’s chamber and stables in 1473. Non-deliberate excavations in the ensuing centuries were revelatory but evidence has presented itself several times- basically, every time someone digs around the area- and especially the oval keep mound beneath the churchyard of Saints Peter and Paul. Mostly the finds are of the masonry of the ancient castle.

From the 10th century until the 18th the town of Buckingham was the capital of the county. Jurisdiction was moved to Aylesbury after that time but Buckingham was important enough to be granted a charter by the Crown (Queen Mary at the time) in 1554 which created a free borough with boundaries of its four bridges- Thornborough, Dudley, Chackmore and Padmury Mill. Even now it is famous as a market town with local shops that are national chains and independent but some of the markets pre-date the charters as far back as the early 15th century! Ancient Roman settlements were found in several areas around the River Ouse including the discovery of a 3rd century temple at Bourton (a suburb of Buckingham) south of the A421 which was excavated in the 1960s. Another such building was discovered at Castle Fields in the 19th century.

The building in the center of town which tries its best to look like part of a medieval castle is actually the Old Gaol (Jail) Museum and is also referred to as Lord Cobham’s Castle. Established as a museum in 1993 the roof was given a new state-of-the-art glass overhead at the turn of the century and serves as the county’s education resource center. Atop Market Hill on High Street it certainly looks impressive but was built in 1748 to stage an Assize (better known to Americans as Kangaroo Court!) Named for its builder, this Revival Medieval edifice is the main tourist attraction for Buckingham and besides being a tourist information center it contains displays on the local geology, archaeology, social history of the area and has a highly informative permanent exhibition on the county yeomanry (farmers or freeholders of land appointed to them by the gentry or royalty). Yeomanry House, the office and home of the commanding officer of the Yeomanry, was built in the early 19th century but at present it serves as an office and reception building for the University of Buckingham and has served this purpose since 1974. In this photo it is the soft pink colored building next to the late 18th century red brick Masonic Hall. Both became dilapidated by the 1960s but received interior refurbishment early in the 1980s to serve the Hunter Street university representation.

The building in the center of town which tries its best to look like part of a medieval castle is actually the Old Gaol (Jail) Museum and is also referred to as Lord Cobham’s Castle. Established as a museum in 1993 the roof was given a new state-of-the-art glass overhead at the turn of the century and serves as the county’s education resource center. Atop Market Hill on High Street it certainly looks impressive but was built in 1748 to stage an Assize (better known to Americans as Kangaroo Court!) Named for its builder, this Revival Medieval edifice is the main tourist attraction for Buckingham and besides being a tourist information center it contains displays on the local geology, archaeology, social history of the area and has a highly informative permanent exhibition on the county yeomanry (farmers or freeholders of land appointed to them by the gentry or royalty). Yeomanry House, the office and home of the commanding officer of the Yeomanry, was built in the early 19th century but at present it serves as an office and reception building for the University of Buckingham and has served this purpose since 1974. In this photo it is the soft pink colored building next to the late 18th century red brick Masonic Hall. Both became dilapidated by the 1960s but received interior refurbishment early in the 1980s to serve the Hunter Street university representation.

T: 01280 823020 Lord Cobham’s open Mondays-Saturday from 10-4

T: 01280 823020 Lord Cobham’s open Mondays-Saturday from 10-4

If you have a hankering to see something medieval at Buckingham you could check out St Rumbold’s Well on the outskirts of the town located on the south side of an old, abandoned railway track. This well was dug to tap a spring line under the crest of a north facing slope which overlooks the town. Bourton, the town I mentioned for its ancient Roman temple, is the location of a mansion that belonged to the Minshull family. During the Civil War the house was plundered by parliamentarian forces and goods valued at £2,000 (a massive fortune at that time) were taken. The house has long since disappeared without a trace. Other tourist attractions include the 15th century Chantry Chapel, also on Market Hill, which is a secondhand bookshop now, Sir George Gilbert Scott’s St. Peter & St. Paul Church and a number of picturesque Georgian streetscapes. An interesting note is that Bernie Marsden, the guitarist and songwriter for Whitesnake, was born in Buckingham, still lives locally and was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Buckingham in 2015!

There are more castle sites in the nethermost regions of the county which are rather obscure or impressive by turns. Lavendon Castle (which is farthest north and north of the modern village of the same name) inexplicably has no less than three baileys in the remaining earthworks but the motte was eventually flattened in 1944 leaving only massive ramparts along the outside of the inner and outer bailey as proof of a former castle site. That, piperolls attesting to its existence from 1086 and 12th century pottery found at the time of the removal of the motte shows that this was a substantial Norman castle in its day. A farmhouse and garden terracing built in the 17th century, known at present as Castle Farm, were located near an abbey which would date from mid-12th century. The original castle works are of John de Bidum, a baronial family who inherited their rights to the land from William de Briwerre. Lavendon became their headquarters. Records of the castle ended by 1232 but the abbey (which was suppressed during the Dissolution) was destroyed in 1536. It stood at what is now Grange Farm.

There are more castle sites in the nethermost regions of the county which are rather obscure or impressive by turns. Lavendon Castle (which is farthest north and north of the modern village of the same name) inexplicably has no less than three baileys in the remaining earthworks but the motte was eventually flattened in 1944 leaving only massive ramparts along the outside of the inner and outer bailey as proof of a former castle site. That, piperolls attesting to its existence from 1086 and 12th century pottery found at the time of the removal of the motte shows that this was a substantial Norman castle in its day. A farmhouse and garden terracing built in the 17th century, known at present as Castle Farm, were located near an abbey which would date from mid-12th century. The original castle works are of John de Bidum, a baronial family who inherited their rights to the land from William de Briwerre. Lavendon became their headquarters. Records of the castle ended by 1232 but the abbey (which was suppressed during the Dissolution) was destroyed in 1536. It stood at what is now Grange Farm.

Lavendon Castle’s motte was greatly reduced and only survives as a low flat-topped plateau 80 meters in diameter and perhaps, 1.4 meters high suggesting that it was never of great height and certainly not rebuilt in stone. The rest of the site is undisturbed and is of great value as an illustration of the organization of outlying medieval landscapes. As it was a private castle there are few records but curiously, was a part of the national defense system in 1193 when Richard I was threatened by the rebellion of his brother, John. In that year it is recorded that twenty loads of wheat were paid for by the exchequer ‘to maintain Lavendon Castle’. A portion of the present site is covered over with 17th century farm buildings but an entrance can be clearly made out along the inner bailey’s southeast side so key areas of the earthworks remain intact. Historically, the castle has been associated with Henry de Clinton and the Peyvers, who were also de Briwerre’s heirs, but the defenses were most likely destroyed altogether after 1530.

South of Lavendon, about ten miles west southwest, another impressively sized earthwork, Castlethorpe, is seated by the River Tove and gives its name to the surrounding town as it is sometimes referred to as Hanslope Castle. This massive site has a deep ditch which marks the site of the original bailey but the motte appears to have been left unfinished or was leveled. The parish church, which can be seen in the photo, parts of which were Norman built, stood inside the bailey during medieval times and was most likely used as the castle chapel. Both were originally built in the 12th century. In 1215 this castle was besieged and destroyed by King John to punish Robert Mauduit, one of the barons who forced the king to sign the Magna Charta. By 1292 the site was revived when William de Beauchamp obtained a license to crenellate from Edward I whereupon he created a new bailey along the west, bounded by a straight rampart with a broad ditch in front. He added a house and garden which were walled as well and stood right by the old earthwork ruins.

South of Lavendon, about ten miles west southwest, another impressively sized earthwork, Castlethorpe, is seated by the River Tove and gives its name to the surrounding town as it is sometimes referred to as Hanslope Castle. This massive site has a deep ditch which marks the site of the original bailey but the motte appears to have been left unfinished or was leveled. The parish church, which can be seen in the photo, parts of which were Norman built, stood inside the bailey during medieval times and was most likely used as the castle chapel. Both were originally built in the 12th century. In 1215 this castle was besieged and destroyed by King John to punish Robert Mauduit, one of the barons who forced the king to sign the Magna Charta. By 1292 the site was revived when William de Beauchamp obtained a license to crenellate from Edward I whereupon he created a new bailey along the west, bounded by a straight rampart with a broad ditch in front. He added a house and garden which were walled as well and stood right by the old earthwork ruins.

Freely accessible

Wolverton Castle is only a few miles south of Hanslope and can be found at old Wolverton (the deserted medieval village which sits just northwest of the modern (19th century) town of Wolverton). Built right next to an ancient Saxon church- Holy Trinity- which was rebuilt in 1819 in the Anglo-Norman style, this motte and bailey’s earthwork remains still stand although a moat was filled in when the church was rebuilt. William the Conqueror granted the land to Manno, a Breton royal, who built a manor. His son, Manfelin, became second baron and founded a Benedictine Priory nearby. Seven barons of Wolverton followed the line until 1351 when Sir Ralph de Wolverton died without an heir and the family line became extinct.

Wolverton Castle is only a few miles south of Hanslope and can be found at old Wolverton (the deserted medieval village which sits just northwest of the modern (19th century) town of Wolverton). Built right next to an ancient Saxon church- Holy Trinity- which was rebuilt in 1819 in the Anglo-Norman style, this motte and bailey’s earthwork remains still stand although a moat was filled in when the church was rebuilt. William the Conqueror granted the land to Manno, a Breton royal, who built a manor. His son, Manfelin, became second baron and founded a Benedictine Priory nearby. Seven barons of Wolverton followed the line until 1351 when Sir Ralph de Wolverton died without an heir and the family line became extinct.

Surprisingly, the historic village is abandoned but field patterns and outlines from ranges and two village ponds remain and can be clearly seen. Desertion of ancient Wolverton was due to reduction of strip cultivation fields to small closes by the local landlords, the Longueville family- nuptial heirs to the Wolverton estate. They converted cultivable land to pasture and by 1654, the family had completely enclosed the parish after 300 years of ownership. With the end of the feudal system, peasants lost the rights to the land and were forced to find work elsewhere. Within a century the old town was reduced to a zero population. The newer Wolverton which is a half mile to the southeast was built in the 19th century for convenience to the railway system.

Earthworks of Wolverton consist of two areas divided by a canal. The motte and bailey reside along the northern part of the deserted village and Holy Trinity church. Adjacent to the castle motte is the bailey area in which stood a variety of buildings in service to the castle. Separated by the canal, the second area to the northeast consists of earthworks surrounding the Manor Farm. Hollow trackways, a pond, building platforms and field systems can be identified and documentary records indicate that this area contains the remains of an agrarian monastic grange, the site of which is considered to be overlain by modern farm buildings. Buried remains of a Roman building were found east of Manor Cottages along with Roman and Saxon coins and metalwork. Holy Trinity Church, its surrounding churchyard, and the vicarage which lies to the south of the castle, are totally excluded from historic scheduling.

Sir John Longueville, who was proprietor in Leland’s time, died at Wolverton in 1537 at the ripe old age of 103. His descendant was created a baronet in 1638 by Charles I and the third baronet sold the manor and castle in 1712 to a popular physician, Dr. Ratcliffe, for about £40,000. The doctor bequeathed Wolverton along with other property, under trust, to the University of Oxford.

Bradwell Castle is located closest to Milton Keynes which is about five miles south and southeast of Castlethorpe. The earthwork remains of the Norman motte and bailey are within Bradwell village district while the Benedictine Priory and Abbey which is in its own small district west of Bradwell just off Vicarage Road is intact, above ground and not far away. In the old part of Bradwell the former castle site is closest to St Lawrence’s Church and survives as a sod covered low-lying earthwork. It appears to be well-excavated but was actually used to construct an air raid shelter during WWII. A relatively small bailey lies along the west side of the motte with a disappearing scarp that runs about 100 yards and ends. No attempt was made to rebuild it in stone.

Bradwell Castle is located closest to Milton Keynes which is about five miles south and southeast of Castlethorpe. The earthwork remains of the Norman motte and bailey are within Bradwell village district while the Benedictine Priory and Abbey which is in its own small district west of Bradwell just off Vicarage Road is intact, above ground and not far away. In the old part of Bradwell the former castle site is closest to St Lawrence’s Church and survives as a sod covered low-lying earthwork. It appears to be well-excavated but was actually used to construct an air raid shelter during WWII. A relatively small bailey lies along the west side of the motte with a disappearing scarp that runs about 100 yards and ends. No attempt was made to rebuild it in stone.

Bradwell Abbey, which was established in the mid-12th century, was closed before the Dissolution in 1524 after the Black Death took the life of Prior William of Loughton. A chapel and manor continue to occupy the spot of the former site of the Abbey. Much that was medieval has been eradicated with the exception of the chapel and roads which exist as Redways (modern pedestrian walkways) or bridleways and the chapel and manor continue to occupy the area with a YHA hostel nearby. The Milton Keynes City Discovery Center has taken over the former Abbey site and holds an extensive archive about Milton Keynes as a research facility and broad education program with its focus on geography and local history.

Bradwell Abbey, which was established in the mid-12th century, was closed before the Dissolution in 1524 after the Black Death took the life of Prior William of Loughton. A chapel and manor continue to occupy the spot of the former site of the Abbey. Much that was medieval has been eradicated with the exception of the chapel and roads which exist as Redways (modern pedestrian walkways) or bridleways and the chapel and manor continue to occupy the area with a YHA hostel nearby. The Milton Keynes City Discovery Center has taken over the former Abbey site and holds an extensive archive about Milton Keynes as a research facility and broad education program with its focus on geography and local history.

Five miles west of Aylesbury and near the border of Oxfordshire, ten miles from the city of Oxford, Boarstall Tower’s estate, perhaps predates the Conquest! Less than a few miles west of Brill and Oakley, it sits on property that was awarded to a forester by a Saxon King. By 1312 the property was owned by Sir John de Haudlo, the Sheriff of Oxfordshire who obtained a license to crenellate the moated manor on September the twelfth. Sir John’s father was a custodian of Tonbridge Castle (in Kent) in the 13th century with which Boarstall’s gatehouse is similar in appearance. What you will see in the present day appears to be the gatehouse of a castle on the north side of the property- a mere remnant of what was to have existed before 1778. The architectural appearance of the gatehouse, however, suggests that it was rebuilt or completely restored in the 1400s when the manor was held by Edmund Rede. Instructions were left in his will, dated April 7, 1487 that he was to be buried in the chapel of the Holy Trinity on the south side altar tomb of the Boarstall Church of St. James. When the church was destroyed during the Civil War, the late 15th century tomb was also destroyed and when salvaged later, it became inconclusive about Rede’s remains.

Five miles west of Aylesbury and near the border of Oxfordshire, ten miles from the city of Oxford, Boarstall Tower’s estate, perhaps predates the Conquest! Less than a few miles west of Brill and Oakley, it sits on property that was awarded to a forester by a Saxon King. By 1312 the property was owned by Sir John de Haudlo, the Sheriff of Oxfordshire who obtained a license to crenellate the moated manor on September the twelfth. Sir John’s father was a custodian of Tonbridge Castle (in Kent) in the 13th century with which Boarstall’s gatehouse is similar in appearance. What you will see in the present day appears to be the gatehouse of a castle on the north side of the property- a mere remnant of what was to have existed before 1778. The architectural appearance of the gatehouse, however, suggests that it was rebuilt or completely restored in the 1400s when the manor was held by Edmund Rede. Instructions were left in his will, dated April 7, 1487 that he was to be buried in the chapel of the Holy Trinity on the south side altar tomb of the Boarstall Church of St. James. When the church was destroyed during the Civil War, the late 15th century tomb was also destroyed and when salvaged later, it became inconclusive about Rede’s remains.

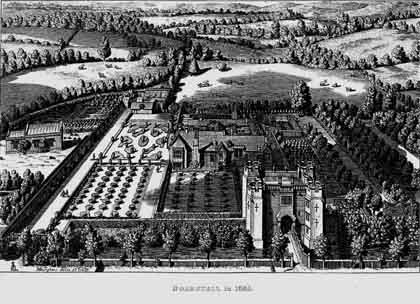

Basically, the configuration of the tower is that of a short oblong block with a central stone gate bridge and hexagonal towers incorporated at the four corners. Boarstall’s entrance towers have the original cross slits and the turrets along the anterior are punctulated with windows and have interior circular stone staircases. The postern turrets also have ground level arched doorways and a 17th clock atop the southwest tower! Inside, on the topmost floor, is the largest chamber within the tower and may be the only part to claim over 700 years of existence- at one time the medieval solar. Boarstall’s estate is a quadrangular ground plan with a wide moat which makes it appear as if it may have been part of a small courtyard castle but there isn’t sufficient information about what was swept away in the 18th century to know for sure how the entire estate was originally built. Extensive Versailles-like gardens depicted in an antiquated drawing of 1695 and the survival of the magnificent moat, at present, are our only clues. It is certain that a large manor house once existed on the property behind the gatehouse and perhaps was the original living quarters of Boarstall. If the towered gatehouse stands alone as fortification of Boarstall then this property may be the grandest anomaly of which England can boast.

Basically, the configuration of the tower is that of a short oblong block with a central stone gate bridge and hexagonal towers incorporated at the four corners. Boarstall’s entrance towers have the original cross slits and the turrets along the anterior are punctulated with windows and have interior circular stone staircases. The postern turrets also have ground level arched doorways and a 17th clock atop the southwest tower! Inside, on the topmost floor, is the largest chamber within the tower and may be the only part to claim over 700 years of existence- at one time the medieval solar. Boarstall’s estate is a quadrangular ground plan with a wide moat which makes it appear as if it may have been part of a small courtyard castle but there isn’t sufficient information about what was swept away in the 18th century to know for sure how the entire estate was originally built. Extensive Versailles-like gardens depicted in an antiquated drawing of 1695 and the survival of the magnificent moat, at present, are our only clues. It is certain that a large manor house once existed on the property behind the gatehouse and perhaps was the original living quarters of Boarstall. If the towered gatehouse stands alone as fortification of Boarstall then this property may be the grandest anomaly of which England can boast.

An account written by Simon Jenkins goes something like this: The story begins in the 11th century. A ferocious boar in the king’s forest of Bernewood was trapped and killed by a wily forester named Nigel. The grateful Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066) gave Nigel a horn- now in the archives at Aylesbury- and land on which to build a house. Nigel’s (extended) family held the house across the entire sweep of English history, until giving it to the National Trust in 1943. Even then, the Aubrey-Fletchers rented it back and sublet it to the present custodians. The old house sat central amongst an extensive garden and walled and moated courtyard. Most of what survives is a magnificent towered gatehouse. It was improved for use as a banqueting house at the end of the 16th century, and includes an upper chamber with windows on all four sides. In a print of 1695, the tower is seen to dominate the old house behind, set in what was then a formal parterre. The property passed through a succession of daughters to the Aubreys but when a six year old Aubrey son died of food poisoning in 1777, the grief-stricken family demolished the main house. The tower was left empty and the gardens overgrown for (nearly) 150 years. Not until 1925 did an Aubrey tenant, Mrs. Jennings Bramley, modernize the property and alter the old entrance to make the present dining room. The tower is reached by a bridge over its remaining moat. The hard lines of 14th century military architecture are softened by later parapets and oriel windows notably over the doorway. The garden behind bears traces of a reported visit by Capability Brown. The interior has been spoilt with National Trust heating and health and safety regulations but the thick walls, cozy bedrooms and glimpsed views over the surrounding landscape more than compensate.

An account written by Simon Jenkins goes something like this: The story begins in the 11th century. A ferocious boar in the king’s forest of Bernewood was trapped and killed by a wily forester named Nigel. The grateful Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066) gave Nigel a horn- now in the archives at Aylesbury- and land on which to build a house. Nigel’s (extended) family held the house across the entire sweep of English history, until giving it to the National Trust in 1943. Even then, the Aubrey-Fletchers rented it back and sublet it to the present custodians. The old house sat central amongst an extensive garden and walled and moated courtyard. Most of what survives is a magnificent towered gatehouse. It was improved for use as a banqueting house at the end of the 16th century, and includes an upper chamber with windows on all four sides. In a print of 1695, the tower is seen to dominate the old house behind, set in what was then a formal parterre. The property passed through a succession of daughters to the Aubreys but when a six year old Aubrey son died of food poisoning in 1777, the grief-stricken family demolished the main house. The tower was left empty and the gardens overgrown for (nearly) 150 years. Not until 1925 did an Aubrey tenant, Mrs. Jennings Bramley, modernize the property and alter the old entrance to make the present dining room. The tower is reached by a bridge over its remaining moat. The hard lines of 14th century military architecture are softened by later parapets and oriel windows notably over the doorway. The garden behind bears traces of a reported visit by Capability Brown. The interior has been spoilt with National Trust heating and health and safety regulations but the thick walls, cozy bedrooms and glimpsed views over the surrounding landscape more than compensate.

The banqueting room above is excellently preserved, with wide windows and a large fireplace. Windows carry heraldic glass and the roof offers a view of the Chiltern escarpment.

The banqueting room above is excellently preserved, with wide windows and a large fireplace. Windows carry heraldic glass and the roof offers a view of the Chiltern escarpment.

Numerous accounts of Boarstall state that the entire complex withstood two separate assaults (and a fierce struggle for possession by the Royalists and Parliamentarians) during the Civil War in 1645 when it was garrisoned by force with Royalists and did not surrender until June of 1646 after a two-month long siege headed by Fairfax. Most likely the gatehouse had to be reconstructed after that time and modern alterations include a bay (oriel) window above the outer archway and a balustrade replaced the parapet. The entire property was fortified with a low wall early in the 17th century before the Civil War and part of it still exists! The 18th century entrance bridge which

Numerous accounts of Boarstall state that the entire complex withstood two separate assaults (and a fierce struggle for possession by the Royalists and Parliamentarians) during the Civil War in 1645 when it was garrisoned by force with Royalists and did not surrender until June of 1646 after a two-month long siege headed by Fairfax. Most likely the gatehouse had to be reconstructed after that time and modern alterations include a bay (oriel) window above the outer archway and a balustrade replaced the parapet. The entire property was fortified with a low wall early in the 17th century before the Civil War and part of it still exists! The 18th century entrance bridge which  crosses over the moat has been completely remodeled, not just restored, most likely by Mrs. Bramley, with two archways of brick and extended and splayed along the west and east of the outer bank of the moat.

crosses over the moat has been completely remodeled, not just restored, most likely by Mrs. Bramley, with two archways of brick and extended and splayed along the west and east of the outer bank of the moat.

Capability Brown, indeed, paid two visits to Boarstall at some point in the 18th century for which he was paid 15 guineas. It explains why all the parterres are missing! The tower sat empty for more than a hundred years but was eventually to be used as a banqueting pavilion in most recent years. Mrs Jennings-Bramley rented Boarstall in 1925, using a portion of the gatehouse for a music room and converted it entirely into living quarters, modifying the original carriageway which once had a portcullis and sealing off the rear archway. In 2008 the National Trust conducted an official dig during National Archaeology Week in which they found five trenches located exactly where they should have been in relation to the position of the old manor house (i.e. the manor house was moated as well). Boarstall is owned by the National Trust but it is also occupied by tenants so access to interiors must be arranged by appointment. The gardens on the property are available for public access from March to September on Wednesdays from 2-5 p.m. During your visit you should check out the elaborate and quite antiquated duck decoy. It’ll be a true educational experience!

National Trust owned since 1943 boarstalltower@nationaltrust.org.uk T:01280817156 tenant: 01844239339

National Trust owned since 1943 boarstalltower@nationaltrust.org.uk T:01280817156 tenant: 01844239339

Bolebec Castle is a motte and bailey site overlooking the village of Whitchurch, commanding the main north-south route which follows the A413 (a short distance northeast of Waddesdon Manor) and delineated by impressively sized ramparts, enclosed by trees. It takes its name from Hugh de Bolebec II, whose illegal castle building attracted criticism from Pope Eugenius III in 1147. Even though no stone has been saved above ground the site still speaks of grandeur and, as a whole, has remained intact as earthworks. Despite total demolition in the 17th century during the Civil War, the motte comprises a purposefully-scarped natural mound approximately five meters high and was constructed by dividing a section of a natural spur to construct an elevated platform. Oval in shape with dimensions of 80 meters north to south and 60 meters east to west, the plateau ends at its northern arc by a very low internal bank. It appears the castle once included a curtain wall around the summit. Vestiges of structures can be identified through the turf covered foundations with a length of twenty-four meters toward the south side of the summit. The south eastern area is level and flat. Two possible entrances to the interior of the motte along the west and north-east are apparent and the west opening may have been the position of an original drawbridge. According to local tradition the stone keep was closest to Market Hill Close and the drawbridge was near Weir pond. The motte is surrounded by a former moat about eight meters wide but only 0.6m deep. Although now dry, except for a marshy area around a spring in the south-east quarter, this may have once been filled with water supplied by the spring. Sections of this moat are supposed to have survived as the course of Castle Lane to the north while the western arch has been destroyed. The bailey spread along the north and to a portion of the spur overtaken by the garden of Bolebec Place House. Castle Lane separates the motte from the bailey and though modified by later landscaping, it consists of a substantial earthen bank about three meters high enclosing a triangular area of level ground.

Bolebec Castle is a motte and bailey site overlooking the village of Whitchurch, commanding the main north-south route which follows the A413 (a short distance northeast of Waddesdon Manor) and delineated by impressively sized ramparts, enclosed by trees. It takes its name from Hugh de Bolebec II, whose illegal castle building attracted criticism from Pope Eugenius III in 1147. Even though no stone has been saved above ground the site still speaks of grandeur and, as a whole, has remained intact as earthworks. Despite total demolition in the 17th century during the Civil War, the motte comprises a purposefully-scarped natural mound approximately five meters high and was constructed by dividing a section of a natural spur to construct an elevated platform. Oval in shape with dimensions of 80 meters north to south and 60 meters east to west, the plateau ends at its northern arc by a very low internal bank. It appears the castle once included a curtain wall around the summit. Vestiges of structures can be identified through the turf covered foundations with a length of twenty-four meters toward the south side of the summit. The south eastern area is level and flat. Two possible entrances to the interior of the motte along the west and north-east are apparent and the west opening may have been the position of an original drawbridge. According to local tradition the stone keep was closest to Market Hill Close and the drawbridge was near Weir pond. The motte is surrounded by a former moat about eight meters wide but only 0.6m deep. Although now dry, except for a marshy area around a spring in the south-east quarter, this may have once been filled with water supplied by the spring. Sections of this moat are supposed to have survived as the course of Castle Lane to the north while the western arch has been destroyed. The bailey spread along the north and to a portion of the spur overtaken by the garden of Bolebec Place House. Castle Lane separates the motte from the bailey and though modified by later landscaping, it consists of a substantial earthen bank about three meters high enclosing a triangular area of level ground.

In spite of the supposed adulterine origin, Bolebec survived Henry II’s accession in 1154, which would be highly unusual because his greatest passion was destroying unlicensed castles. Because Whitchurch was granted to Walter de Bolbec by William the Conqueror in the wake of the Norman Conquest it would’ve been unlikely that any demolition would be carried out, being as how Walter was actually a distant cousin. (They shared descent from their great, great grandmother Josceline, the wife of Herbastus de Crepon.) De Vere Earls of Oxford took possession of Bolbec and rebuilt the castle in stone by 1245 similar to their Hedingham Castle in Essex becoming the stronghold of both de Bolbec and de Vere families. A village market was established at Whitchurch concurrently.

By the time of the Civil War the castle’s proximity to the Royalist capital at Oxford made it a clear candidate for reactivation and it was garrisoned for King Charles. By the end of the war it was taken over by Parliamentary forces and though this action went unrecorded, archaeological discoveries suggest that artillery was used to reduce the castle. It was subsequently slighted and the masonry was pillaged for local building repairs elsewhere. Part of the gatehouse survived until the late 18th century but it has vanished like the rest. Freely accessible.

More motte and baileys abound as we get closer to Aylesbury. The former Cublington Castle is only six miles north of Aylesbury and is situated near the earthworks of the abandoned original church and village from the 15th century. You’ll find the earthworks of the castle on farmland with a path that is spread out along one side of the site. A motte of about a hundred feet in diameter and twenty-five feet high is quite easy to see from the footpath and it’s supposed to be the best preserved site of its kind in the county. The castle’s earthworks were constructed ca. 1100 or during the 11the century. As an extensive motte and bailey overlooking the Vale of Aylesbury its height is insufficient although the area affords some wonderful views of the Vale.

More motte and baileys abound as we get closer to Aylesbury. The former Cublington Castle is only six miles north of Aylesbury and is situated near the earthworks of the abandoned original church and village from the 15th century. You’ll find the earthworks of the castle on farmland with a path that is spread out along one side of the site. A motte of about a hundred feet in diameter and twenty-five feet high is quite easy to see from the footpath and it’s supposed to be the best preserved site of its kind in the county. The castle’s earthworks were constructed ca. 1100 or during the 11the century. As an extensive motte and bailey overlooking the Vale of Aylesbury its height is insufficient although the area affords some wonderful views of the Vale.

Wing Castle is just a bit further north and east of Cublington approximately eight miles and almost equidistant of Aylesbury. This town received some keen attention in the year 2000 when the BBC ran a program called Meet the Ancestors in which a recreation of the face of an Anglo-Saxon girl who’d been buried in the old graveyard of the parish church was carried out. All Saints Church at the town is the oldest continuously used religious site in England so the evidence and recreation was of particular significance to the populace of the entire country. The girl’s remains became part of the evidence indicating the site has had religious use going back well over 1300 years.

A covered-over earth motte is situated high on a natural slope above Wing on the North and West sides. Measuring thirty meters in diameter and four meters high along the southeast side and six meters high northwest, the summit has been irretrievably altered from excavation or plowing and a road now runs through the southeast edge. As a reasonable defensive position, and its situation within Wing indications are of a former castle site although no ditch or outer rampart can be distinguished. Evidence for a bailey is missing though a low scarp extending on the northeast side of the mound could be remains. An area sited to be a logical position for the bailey on level ground southeast of the motte is now occupied by housing.

Aylesbury is located right in the center of every town and major landmark in Buckinghamshire so it was apt that it became the county town. Buckingham held that distinction for many centuries but in 1529, King Henry VIII declared that the town which fostered his new marriage interest, a Boleyn, would be the new county town. Aylesbury Manor had become a property of Thomas Boleyn and so it is widely believed that the king did so in order to gain favor with the family. Certainly, it was not an unfounded action. Besides being an obvious convenience to the people of the county, Aylesbury was once the stronghold of the ancient Britons and was taken in the year 571 by Cutwulph, the brother of Ceawlin– the King of the West Saxons- where he had raised a fortress of great size. Both town and castle were obviously named for him. Excavations carried out in the town center in 1985 unearthed an Iron Age hill fort which dated from the early 4th century B.C. Some 18th century abodes still grace Castle Street near the Temple Square triangle but apparently there is no record of specifically where Aylesbury Manor existed and the Iron Age hillfort may be the only source of raw material to discover anything of that period.

Aylesbury is located right in the center of every town and major landmark in Buckinghamshire so it was apt that it became the county town. Buckingham held that distinction for many centuries but in 1529, King Henry VIII declared that the town which fostered his new marriage interest, a Boleyn, would be the new county town. Aylesbury Manor had become a property of Thomas Boleyn and so it is widely believed that the king did so in order to gain favor with the family. Certainly, it was not an unfounded action. Besides being an obvious convenience to the people of the county, Aylesbury was once the stronghold of the ancient Britons and was taken in the year 571 by Cutwulph, the brother of Ceawlin– the King of the West Saxons- where he had raised a fortress of great size. Both town and castle were obviously named for him. Excavations carried out in the town center in 1985 unearthed an Iron Age hill fort which dated from the early 4th century B.C. Some 18th century abodes still grace Castle Street near the Temple Square triangle but apparently there is no record of specifically where Aylesbury Manor existed and the Iron Age hillfort may be the only source of raw material to discover anything of that period.

During your travels in Buckinghamshire you can’t go wrong in seeking out interesting accommodation at Aylesbury and it’s quite a cool town, if I do say so myself. It’s rather offbeat and even its history, as you soak it in, backs me up on this conjecture. Their heraldic crest emblazons an Aylesbury duck and it’s a rather odd duck, at that. The Friar’s Club is where you want to go to check out rock and roll talent and just hanging about you can sense in the atmosphere the greatness that once graced the stage. It’s also where you’ll catch up with the current Market Square heroes. If you decide to stick around please check out Poletrees Farm which is at Brill on Ludgershall Road. It’s sheer, pure 15th century charm with 21st century luxury. www.poletreesfarm.co.uk You’ll want to visit the County Museum especially if you have kids in tow. It is located on Church Street not far from St. Mary’s Church.

South east of Aylesbury a few miles and off the A41 at Weston Turville, another motte with two bailies can be visited which is connected with Bishop Odo (the half brother of William the Conqueror) and later Henry I granted this castle to the Earl of Mellent who was later created Earl of Leicester by becoming the king’s right hand. During the reign of King John it was in possession of the family of Turville and thus- the name. (Pottery of Saxon-Norman origin was found by Renn and these shards are now in situ at the Aylesbury Museum.) This large but low motte which most certainly had a castle of timber at one time, may not have been built in stone in the ensuing centuries. It had bailies of twin size with the southern bailey larger in circumference than the motte. The second bailey was formed along the east. Only remnants of a ditch remain on the site which means they were mostly filled in at a later time. All of this was ordered to be dismantled by Henry II in 1173 and you can be sure it was carried out but it is a subject of debate why he did so. Even though a license to fortify or refortify the site was granted to the de Moleyns in 1333 it is unlikely that these grants were ever carried out for the castle site.

At some point a manor was built separately from the original motte and bailey but very close by and the estate was divided into three because of claimants who may not have been part of the same family. This was done in the middle of the 14th century and the family of de Moleyns were recorded as owners. They were granted a license to crenellate “the site of their manor of Weston Turvill Buks” by Edward III in January of 1333 and in fact, John and Egidia de Moleyns left behind a very distinct outline of a moat of this castellated house. Eventually the manor was sold to the Duke of Buckingham and most recently, toward the end of the 20th century Baron Anthony de Rothschild of Waddesdon took it on.

Just north of the village of Dinton, southwest of Aylesbury off the A418 on Oxford Road and close to the village Stone, you’ll find a rather interesting and odd folly which was constructed on Saxon burial grounds and situated on a grassy hill quite near the old location of Dinton Hall. Dinton Castle was built in 1769 as an eye catcher and a way for Sir John Vanhatten to store his collection of fossils right within the limestone walls! This small structure really does look like part of the ruins of a castle from a distance but once you’re very close you can see the ammonite fossils in the Portland Limestone

Just north of the village of Dinton, southwest of Aylesbury off the A418 on Oxford Road and close to the village Stone, you’ll find a rather interesting and odd folly which was constructed on Saxon burial grounds and situated on a grassy hill quite near the old location of Dinton Hall. Dinton Castle was built in 1769 as an eye catcher and a way for Sir John Vanhatten to store his collection of fossils right within the limestone walls! This small structure really does look like part of the ruins of a castle from a distance but once you’re very close you can see the ammonite fossils in the Portland Limestone  walls which look quite interesting and with a decorative patina. The close-up I’ve added here of the outside walls shows how beautiful it actually appears. A visit to the site reveals a two-story octagonal building with two circular adjacent towers three stories high. In the video link I’ve added you see how different the structure looks at nearly every angle.

walls which look quite interesting and with a decorative patina. The close-up I’ve added here of the outside walls shows how beautiful it actually appears. A visit to the site reveals a two-story octagonal building with two circular adjacent towers three stories high. In the video link I’ve added you see how different the structure looks at nearly every angle.

At some later point in time it was used as a temporary meeting place for a local non-conformist religious congregation who used a temporary tarpaulin for a makeshift roof because it was built without such. Apparently, it was never intended as a dwelling place. After being neglected for quite a few years the Aylesbury Vale District Council took on the responsibility for renovating the folly and converting it into a two bedroom dwelling, only a little more than a year ago. Prior to this, it was afforded scaffolding to keep it from falling apart altogether.

In late 2012 the castle was sold to Brett O’Connor for £56,000 and under these auspices he has pledged to work with local councils and English Heritage to return this Grade II listed folly into a place where his family can stay on weekends. The auction took place on a November afternoon in Aylesbury along with other bidders. Mr. O’Connor planned to restore the building using authentic limestone from the area and estimated, at the time, that it could be completed within five years. It should be done by now but judging from the present state perhaps this successful businessman has been quite distracted by something else. The new owner planned to restore it to a three-storey building with a staircase in the east tower and fireplace on each floor.

In late 2012 the castle was sold to Brett O’Connor for £56,000 and under these auspices he has pledged to work with local councils and English Heritage to return this Grade II listed folly into a place where his family can stay on weekends. The auction took place on a November afternoon in Aylesbury along with other bidders. Mr. O’Connor planned to restore the building using authentic limestone from the area and estimated, at the time, that it could be completed within five years. It should be done by now but judging from the present state perhaps this successful businessman has been quite distracted by something else. The new owner planned to restore it to a three-storey building with a staircase in the east tower and fireplace on each floor.

Although there is a public footpath, remember that the castle and the land are privately owned.

Cymbeline’s Castle (which has also been called Ellesborough Castle because it’s so close to Ellesborough Church) is a prime example of an intact motte and bailey with features still quite apparent. Sitting high on a portion of a spur below Beacon Hill (the northern edge of the Chiltern escarpment) it gives a breathtaking view of Ellesborough and Little Kimble and the Vale of Aylesbury and is north of Great Kimble. A plateau on the summit reveals only dimensions of an invisible timber tower along with a smaller semicircular annex on the north side slope. Along the west side of the motte, a narrow terrace skirts the base delineating a steep gradient at the end of the spur. All encircled by a shallow and narrow ditch, dividing the motte from two baileys. On the south, the larger bailey is square measuring at forty meters and also partially enclosed by a ditch adjoined with the motte ditch. The south bailey leads into a natural defense of a steep slope leading into Velvet Lawn, a ravine which flanks the spur. A bridge that spanned the ditch and ascended the motte can be seen by a break in this bank near the northern end. The rectangular north bailey most likely was formed later and is only separated from the south with a causeway which was the last construction of the site. It also is surrounded by an obvious and broad ditch. This site is dated by pottery fragment discoveries of the 13th to 15th centuries within the baileys. In addition, Iron Age and Romano-British matter and pottery have been discovered east of the area and at the summit of the motte. Local tradition states that the Iron Age king, Cunobelinus which was Shakespeare’s Cymbeline resided in these hills.

Cymbeline’s Castle (which has also been called Ellesborough Castle because it’s so close to Ellesborough Church) is a prime example of an intact motte and bailey with features still quite apparent. Sitting high on a portion of a spur below Beacon Hill (the northern edge of the Chiltern escarpment) it gives a breathtaking view of Ellesborough and Little Kimble and the Vale of Aylesbury and is north of Great Kimble. A plateau on the summit reveals only dimensions of an invisible timber tower along with a smaller semicircular annex on the north side slope. Along the west side of the motte, a narrow terrace skirts the base delineating a steep gradient at the end of the spur. All encircled by a shallow and narrow ditch, dividing the motte from two baileys. On the south, the larger bailey is square measuring at forty meters and also partially enclosed by a ditch adjoined with the motte ditch. The south bailey leads into a natural defense of a steep slope leading into Velvet Lawn, a ravine which flanks the spur. A bridge that spanned the ditch and ascended the motte can be seen by a break in this bank near the northern end. The rectangular north bailey most likely was formed later and is only separated from the south with a causeway which was the last construction of the site. It also is surrounded by an obvious and broad ditch. This site is dated by pottery fragment discoveries of the 13th to 15th centuries within the baileys. In addition, Iron Age and Romano-British matter and pottery have been discovered east of the area and at the summit of the motte. Local tradition states that the Iron Age king, Cunobelinus which was Shakespeare’s Cymbeline resided in these hills.

A market town, Chesham situated in the Chiltern Hills 11 miles southeast of Aylesbury and is so named because it is nestled in the Chess Valley. Henry III granted the town a royal charter for a weekly market in 1257 and it remained at that status through hundreds of years. It was most prosperous during the 18th and 19th centuries because of the advance of the manufacturing industry and the historic architecture is primarily Victorian. The name of Chesham is Old English meaning the river-meadow of the stone castle and evidence has been found of a Roman villa nearby where grapevines were planted. Lady Ælfgifu, who was the wife of King Easwig, held an estate at Chesham in 970 which she bequeathed to Abingdon Abbey. Prior to 1066 three adjacent estates of Chesham were recorded in the Domesday book. One such manor was owned by Queen Edith, the widow of Edward the Confessor. After 1066 Edith’s estate was divided by William the Conqueror and given to his half brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Hugh de Bolbec. Not surprisingly, given the local allegiances to John Hampden, the towns’ people largely sided with the Parliamentarians at the outbreak of the English Civil War. During 1642 the influential Parliamentarians John Pym and Earl of Warwick were headquartered in the town along with large numbers of troops. There are records of skirmishes in the area during 1643 when Prince Rupert was stationed near Aylesbury (and sent warnings to Boarstall to bolster their fortifications). Robert Dormer, 1st Earl of Carnarvon pillaged nearby towns, such as Wendover. Heading toward Chesham a company of horsemen of the Parliamentary Army from the town met them outside Great Missenden, a short distance away, where a skirmish took place ending with the Parliamentary force being driven back. From miles off the town can be easily

A market town, Chesham situated in the Chiltern Hills 11 miles southeast of Aylesbury and is so named because it is nestled in the Chess Valley. Henry III granted the town a royal charter for a weekly market in 1257 and it remained at that status through hundreds of years. It was most prosperous during the 18th and 19th centuries because of the advance of the manufacturing industry and the historic architecture is primarily Victorian. The name of Chesham is Old English meaning the river-meadow of the stone castle and evidence has been found of a Roman villa nearby where grapevines were planted. Lady Ælfgifu, who was the wife of King Easwig, held an estate at Chesham in 970 which she bequeathed to Abingdon Abbey. Prior to 1066 three adjacent estates of Chesham were recorded in the Domesday book. One such manor was owned by Queen Edith, the widow of Edward the Confessor. After 1066 Edith’s estate was divided by William the Conqueror and given to his half brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Hugh de Bolbec. Not surprisingly, given the local allegiances to John Hampden, the towns’ people largely sided with the Parliamentarians at the outbreak of the English Civil War. During 1642 the influential Parliamentarians John Pym and Earl of Warwick were headquartered in the town along with large numbers of troops. There are records of skirmishes in the area during 1643 when Prince Rupert was stationed near Aylesbury (and sent warnings to Boarstall to bolster their fortifications). Robert Dormer, 1st Earl of Carnarvon pillaged nearby towns, such as Wendover. Heading toward Chesham a company of horsemen of the Parliamentary Army from the town met them outside Great Missenden, a short distance away, where a skirmish took place ending with the Parliamentary force being driven back. From miles off the town can be easily  distinguished by the spire of 12th century St. Mary’s Church, which was redesigned by George Gilbert Scott in the 19th century.

distinguished by the spire of 12th century St. Mary’s Church, which was redesigned by George Gilbert Scott in the 19th century.

Chesham and High Wycombe dominate the southern portion of the county, where there are a few former castle sites, surprisingly close to London. One such site Little Missenden is a couple of miles west and south of Chesham off the A413 (and south of Great Missenden) Here, a medieval motte and bailey survive as earthworks. Investigations carried out without excavations in 1971 revealed reasonable sized dimensions of the motte (diameter of 27 m and height of 1.7 m) and oval-shaped south bailey measuring 35 meters east-to-west and enclosed by high ramparts. An outer ditch was found along the northwest which most likely surrounded the motte and bailey site at one time but no entrance or causeway was discernible. There is also Little  Missenden Manor house which originated in the 16th century as a late medieval timber-framed hall house. In the 17th century it was extended in red brick, and retains gables and a staircase from that period. By the 18th century it was given a new façade and still exists in the village to this day.

Missenden Manor house which originated in the 16th century as a late medieval timber-framed hall house. In the 17th century it was extended in red brick, and retains gables and a staircase from that period. By the 18th century it was given a new façade and still exists in the village to this day.

White Leaf Cross near Princes Risborough

White Leaf Cross near Princes Risborough

The Thames Valley area is considered an AONB which simply means that it is officially designated as an area of outstanding natural beauty. This special district stretches south to the river Thames at Marlow and reaches all the way north to the highest point of the Chilterns hills at Coombe Hill which is further north than the town of Princes Risborough where the Black Prince held the manor there from the time of his 14th birthday in 1344 ‘til 1376, when he died. This is the Wycombe district, officially, and has a lot of royal connections and history. You’ll find most of the architecture Georgian and the towns of it charmingly quaint and quiet. High Wycombe is a part of this area but happens to be the largest town in Buckinghamshire. Two mottes of castles exist at High Wycombe with one on the grounds of Castle Hill house (which also happens to be the town’s museum) and Desborough Castle, located in a suburb of the town

The Thames Valley area is considered an AONB which simply means that it is officially designated as an area of outstanding natural beauty. This special district stretches south to the river Thames at Marlow and reaches all the way north to the highest point of the Chilterns hills at Coombe Hill which is further north than the town of Princes Risborough where the Black Prince held the manor there from the time of his 14th birthday in 1344 ‘til 1376, when he died. This is the Wycombe district, officially, and has a lot of royal connections and history. You’ll find most of the architecture Georgian and the towns of it charmingly quaint and quiet. High Wycombe is a part of this area but happens to be the largest town in Buckinghamshire. Two mottes of castles exist at High Wycombe with one on the grounds of Castle Hill house (which also happens to be the town’s museum) and Desborough Castle, located in a suburb of the town  by the same name. High Wycombe’s Museum at Castle Hill house sits directly adjacent to the unnamed former castle site which is inexplicably crowned by a tiny late 18th century folly! This may have been done to show the validity of the earthwork but doing so may have been folly on someone’s part. Pun intended. T.I.C. 5 Eden Place Tel: 01494 421892

by the same name. High Wycombe’s Museum at Castle Hill house sits directly adjacent to the unnamed former castle site which is inexplicably crowned by a tiny late 18th century folly! This may have been done to show the validity of the earthwork but doing so may have been folly on someone’s part. Pun intended. T.I.C. 5 Eden Place Tel: 01494 421892

The Desborough site, situated between Desborough and Castlefield, became a Norman ringwork, overlying a mound which could be an earlier burial mound reused later as a Saxon moot. Defenses of the ringwork enclose a small area consisting of a single rampart with a ditch and a break in the middle of the southeast side. Archaeological discoveries indicate a substantial building within the enclosure during the medieval period. More earthworks which have been altered have been found west of this site but were more likely from a much earlier time and appear to be a rampart of an Iron Age fort which was skillfully hidden, overlooking the Wye Valley. There is speculation about the possibility that Desborough was used as a siege castle during the Anarchy because an excavation in the 1980s indicates abandonment by the 12th century.

Further south Harlequin’s Castle is a few miles north of Slough and northeast of Dorneywood Manor and Gardens in an ancient forest area known as Burnham Beeches. This shallow, courtyard-style moat exists as part of the old forest. Also known as Hartley Court and considered a medieval moated island it is quite large in size and most likely only built in timber and wood and fed by natural rainfall and source. On the site there are obvious demarcations and subdivisions in the ground surface suggesting the position of structures no longer standing. A medieval deer park existed around the area but it is strangely quiet and deserted. One can only imagine what once stood on these grounds.

Further south Harlequin’s Castle is a few miles north of Slough and northeast of Dorneywood Manor and Gardens in an ancient forest area known as Burnham Beeches. This shallow, courtyard-style moat exists as part of the old forest. Also known as Hartley Court and considered a medieval moated island it is quite large in size and most likely only built in timber and wood and fed by natural rainfall and source. On the site there are obvious demarcations and subdivisions in the ground surface suggesting the position of structures no longer standing. A medieval deer park existed around the area but it is strangely quiet and deserted. One can only imagine what once stood on these grounds.

Excellent post. I used to be checking constantly this blog and I’m inspired! Very helpful info particularly the remaining section 🙂 I maintain such info a lot. I was seeking this certain information for a very long time. Thanks and good luck.

LikeLike