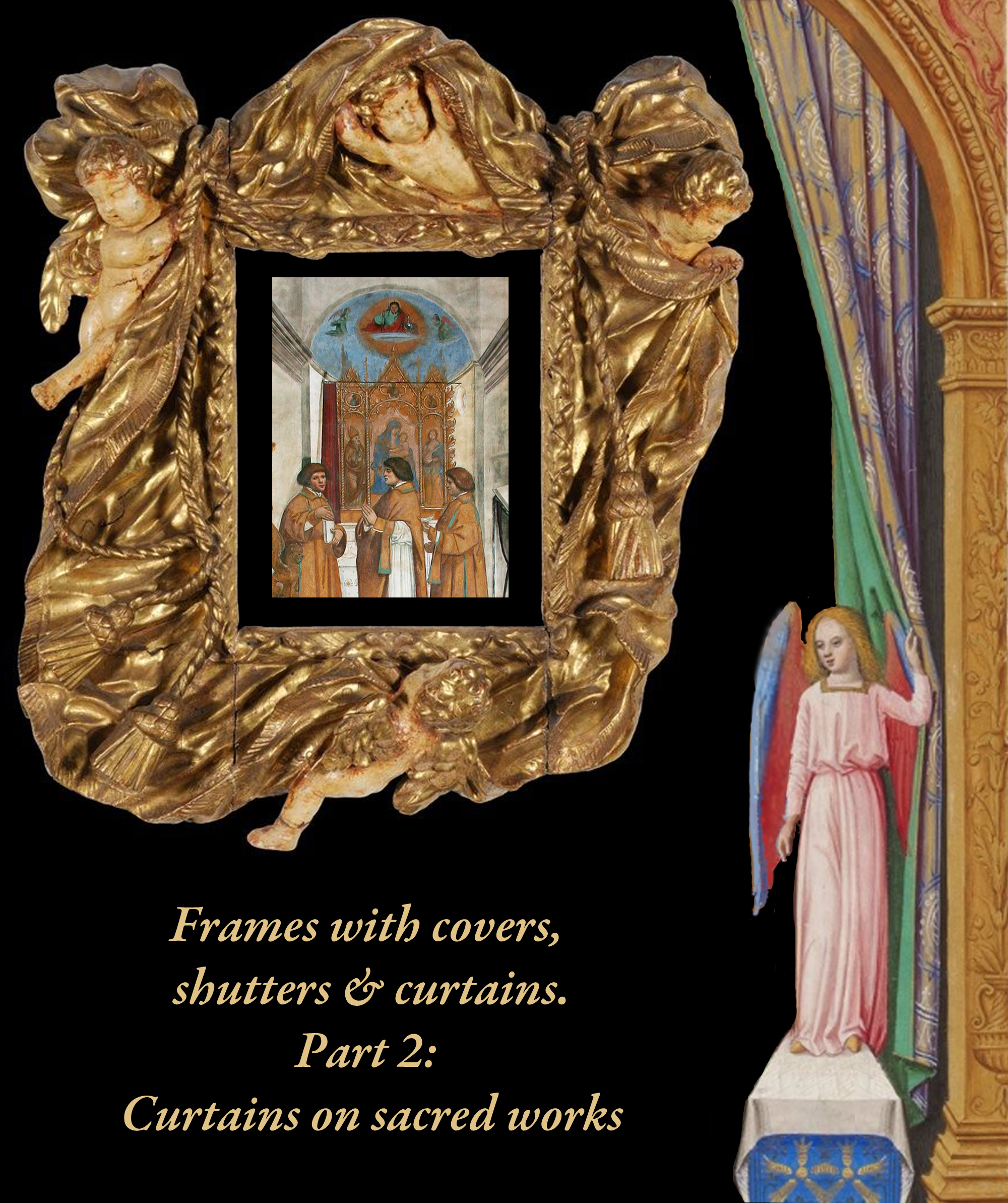

An introduction to frames with covers, shutters and curtains. Part 2: Curtains on sacred works

by The Frame Blog

The second of a triptych of articles; the first, on shutters and covers of sacred works, is available here. This present one explores curtains around the outside of altarpieces, painted curtains inside them, Lenten veils, and the curtains made to hang from rails attached to frames.

Early examples of sacred curtains

Apart from hinged shutters, an important way of concealing and revealing an altarpiece for liturgical effect was by means of curtains – a method which had existed before the beginning of the early Christian church, and derived ultimately from the veiling of statues in classical temples: with references notably to the temples of Artemis at Ephesus, and to a purple wool curtain at the temple of Zeus at Olympia [1]:

‘In Olympia there is a woollen curtain, adorned with Assyrian weaving and Phoenician purple, which was dedicated by Antiochus, who also gave as offerings the golden aegis with the Gorgon on it above the theatre at Athens. This curtain is not drawn upwards to the roof as is that in the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, but it is let down to the ground by cords.’[2]

In the Christian sense, it was associated particularly with the curtain shutting off the Holy of Holies in the rebuilt (or Second) Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, which is described by Josephus (b.37/38-100) :

‘As to the holy house itself… that most sacred part of the temple… Its front was covered with gold all over, and through it the first part of the house, that was more inward, did all of it appear… it was only the first part of it that was open to our view… the inner part was lower than the appearance of the outer, and had golden doors of fifty-five cubits altitude, and sixteen in breadth; but before these doors there was a veil of equal largeness with the doors. It was a Babylonian curtain, embroidered with blue, and fine linen, and scarlet, and purple, and of a contexture that was truly wonderful. Nor was this mixture of colours without its mystical interpretation, but was a kind of image of the universe; for by the scarlet there seemed to be enigmatically signified fire, by the fine flax the earth, by the blue the air, and by the purple the sea; two of them having their colours the foundation of this resemblance; but the fine flax and the purple have their own origin for that foundation, the earth producing the one, and the sea the other. This curtain had also embroidered upon it all that was mystical in the heavens, excepting that of the [twelve] signs, representing living creatures.’ [3]

Johann Daniel Preissler (? signature reads I.M. Preissler; 1666-1737), ‘Der Vorhang im Tempel’, engraving, Kupfer Bibel, 1735, plate 708

It is this curtain which is torn in two as Christ dies on the Cross:

‘Jesus, when he had cried again with a loud voice, yielded up the ghost. And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom.’[4]

The symbolic significance of this was that the Holy of Holies was no longer hidden from the people, but that, by the death of Christ, all were given free access to God [5]. Curtains, or depictions of curtains in frescos, were therefore part of the furnishings of churches from an early point, and were used as a means to and an indication of revelation.

The evolution of painted curtains in and around altarpieces

Frescos showing curtains hanging along the lower walls in Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome: top and centre, left aisle; bottom, in the Chapel of the Holy Physicians, c. 705-07. Photos: Parco Archeologico del Colosseo, Dr Sophie Hay, Dr Steven Zucker [6]

For example, Santa Maria Antiqua, which was established in the remains of a Roman guardhouse in The Forum during the 6th century, has frescos painted there in the early 8th century which include trompe l’oeil curtains hung beneath scenes of Christ and the saints, as if to indicate two states of being for those scenes – curtained in the past and revealed to humanity in the present.

School of Byzantium or Ravenna, altar frontal, c.540-600, marble, overall: 39 ¾ x 66 ¾ ins (101 x 169.5 cm.), The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund 1948.25

The curtains carved in this altar frontal around a door-like opening in the stone probably revealed less a metaphorical than an actual saint. The whole frontal has been composed to imitate the façade of a Byzantine Christian sarcophagus, with its shell-headed niches (standing for baptism), lambs (the Agnus Dei, for Christ), and palms (eternal life), only its size precluding this use. The relationship with a sarcophagus suggests that it may have fronted an altar erected over the tomb of a martyred saint, and that this formed his or her reliquary, with the curtained door an opening through which the faithful could look at the holy remains; a different but no less effective means of revelation. The top of the curtain is beautifully detailed, with its rings and rail, pierced, and looking as though it might really be drawn open or closed.

Ciborium, with 6th century columns, canopy of 1277 and rods to support curtains, in the Basilica of Euphrasius, Istria, Croatia

The columned and curtained doorway of the frontal anticipates, or parallels, the use of ciboria – much larger open stone canopies raised over the altar, with metal rods between the supporting corner columns on which curtains ran; these could be closed around the altar or opened during the service, as the liturgy required. In Coptic and Armenian churches, the whole east end with the altar could, and still can, be closed off from the congregation by means of a curtain drawn across the width of the church.

Curtains painted in fresco on the altar wall around the Pollaiuolo altarpiece (original frame, copy of painting), 1460-73, Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal, San Miniato al Monte, Florence

Nanni di Bartolo (fl. 1419-37) & Pisanello (pre-1390-c.1455), monument to Niccolò Brenzoni, marble, Annunciation, fresco, c.1424-26, San Fermo Maggiore, Venice

Further west, a memory of the curtaining-off of altars in this way survives in the painted trompe l’oeil curtains drawn back, often by angels, on the wall supporting an altarpiece, as though Christ, the Madonna or the saints in the painting were being divinely revealed as literally present in the chapel. This is also true of the stone curtains drawn back from 15th century funerary monuments, disclosing the sarcophagus, usually with a sculpture of its occupant, and a relief or carved figure above showing the Madonna and Child, Christ or God the Father. Here the revelation is of death giving way to resurrection and eternal life, and is itself not so much a metaphor as a direct expression in earthly stone of the imagined journey upwards of the soul, from the sarcophagus to the celestial company carved above it.

Matteo Civitali of Lucca (workshop; 1436-1501), marble tabernacle, dated 1498, 276.86 x 157.48 cm., from the Cathedral of Lucca, now © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Funerary monuments and ciboria can also be seen behind the construction of the carved marble tabernacles installed near to altars, to hold any of the Eucharistic wafers which might remain after Mass, and which were required to be locked away in a symbolically appropriate safe. They take the form of flattish relief carvings, some of which represent perspectival entrances and porticoes around the central door, and some of which have minimal draperies and canopies around the doors. The example (above) from Lucca, now in the V & A, is notable for the curtained pavilion within the architectural frame, with two angels lifting the curtains up from the inside in a particularly dramatic gesture of revelation.

This pavilion is itself a ciborium; and the angels can be seen as both closing the curtains to protect the miracle of transubstantiation, and opening them onto the sacramental transformation of the wafers, as though they were expressing the central act of the Mass through their movements, in a sort of sacred ballet.

Master of the St Godeliva legend (Netherlandish school; fl. 4th quarter 15th century), Life and miracles of St Godeliva, detail of central panel of polyptych, o/panel, open: 125.1 x 311 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Both the ciborium and the curtained-off altar evolved, in mediaeval Europe, into an arrangement of flat curtains hanging behind the altar, with side curtains (known as riddel curtains) projecting outwards towards the body of the church. In the illustration above, giltwood angels are carved on the riddel posts which hold the curtain rails, and a hanging pyx, which is itself ‘curtained’ in matching fabric, is suspended over the altar. The curtains are every-day green, and the altarpiece itself is open and revealed for the sacrament of marriage which is being performed.

An illustration from a French breviary, c.1511, MS M. 8, fol. 189r, two details of the painting, The Morgan Library & Museum

This illustration from a French breviary has the altar and pyx curtained in red, for Passion week; there may be an altarpiece behind the rear curtain, or this may be just the rest of the curtaining-off of the altar. The armorial bearings beneath the text on this illuminated MS page are also revealed by drawn-back curtains.

Fra Angelico, Pala di San Marco, 1438-43, tempera/panel, 220 x 227 cm., San Marco Museum, Florence

Curtains became an important instrument of concealment, withdrawal, revelation and disclosure in the altarpieces and other sacred paintings which formed such an important part of these churches, furnished as they were with sets of hangings for different times and seasons which were constantly in motion across or around the images. The curtained ciborium and the opened altar curtains are both evoked in, for instance, Fra Angelico’s altarpiece for the Convent of San Marco, commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici as part of his rebuilding of church and monastery. The ciborium has become the Madonna’s throne, and the curtain a cloth of honour, but throne and cloth still represent an altar, as holding the body of Christ, and therefore the golden curtains drawn back to the sides are a means of revelation. They are woven with a pattern of roses, the Madonna’s attribute, echoing the festoons of real roses which hang behind them.

Hugo van der Goes (1440-82), Adoration of the shepherds, c.1480, o/panel, 99.9 x 248.6 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Photos: with thanks to Peter Schade

Fra Angelico’s altarpiece, with its population of saints and angels, is presumably set in Heaven, just as Hugo van der Goes’s Adoration is set on earth, amongst cottages, shepherds and sheep, where the angels are merely visiting. The curtains here have moved to the very front of the picture plane, where they ‘hang’ from a three-dimensional rail glued to the top edge of the panel and painted with illusionist highlights, shadows and curtain rings. Two figures, the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah, draw them back as if in front of a stage, welcoming the spectators – the worshippers – to see the Nativity inside.

This is a different kind of revelation, which carries echoes of the mediaeval mystery plays (often performed in churches), laden with the sense of a human scene being played out eternally before divine and human eyes. In the background scenes nearest the curtains, other parts of the story take place – on the left, in the village with its peasant musicians, from which the shepherds have come into the stable, and on the right, on the sheep-covered hillside, where an angel announces the birth of the Saviour. Whilst some of this painting is hyper-realistic, therefore, other areas draw together different periods of time, underlined by the foreground figures, who – being Old Testament prophets who foretold the coming of Christ – must belong in the distant past of the Incarnation: although they are the go-betweens who are the liaison with the real world, who open the curtains from it into their own future.

On the other hand, the curtains are also metaphorical analogues of the curtains around an altar during a Mass; the acolytes open them on the symbolic Incarnation of the Eucharist, where bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ.

Raphael (1483-1520), Sistine Madonna, 1513-14, o/c, 269.5 x 201 cm., with detail of curtain rail, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

More than thirty years later, Raphael provides his Madonna with her own, very similar rail and rings (completely painted in this case), holding up more green curtains (green is, as it were, the default colour for hangings and vestments in the Church, with purple for Lent and Advent, white for Christmas, Easter and saints’ days, red for the Passion days and Pentecost, and black and pink for a few other miscellaneous occasions [7]).

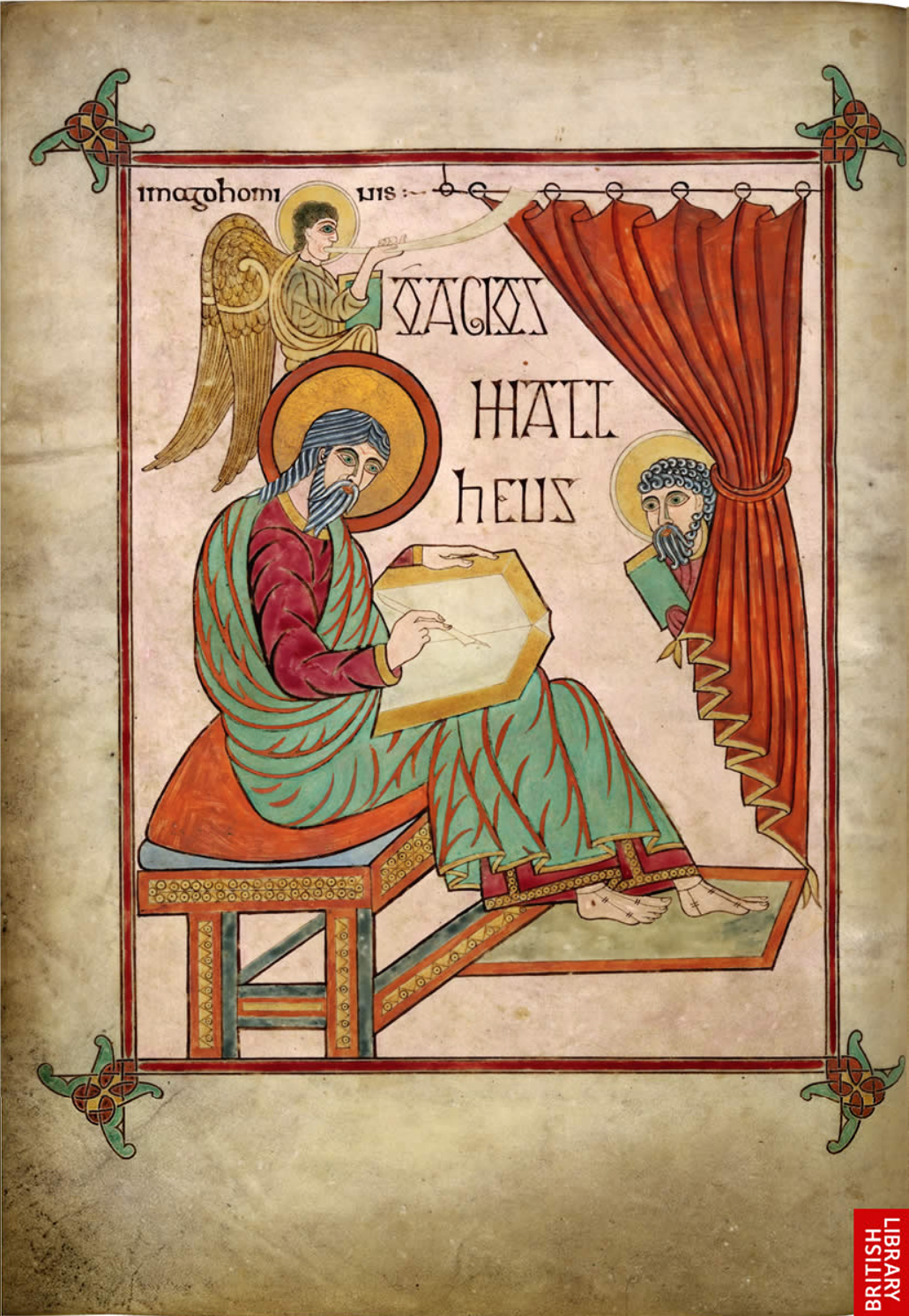

St Matthew, Lindisfarne Gospels, c.700, f. 25v, © The British Library Board

In his article on Raphael’s curtains, Johann Eberlein, having recapitulated the variously vague explanations which have been advanced by a long procession of art historians, connects them with images of Byzantine rulers and evangelists (above) shown on curtained thrones – a connection which was merged with the rending of the temple curtain on Christ’s death, and was later transferred to images of the enthroned or standing Madonna, the means of Christ’s Incarnation [8]. The use of ciboria in churches is also a probable connection. Raphael’s curving rail and curtain rings make it clear that this is an iteration of the temple curtain, split in half to allow access for all the world to the Holy of Holies, expressed in Christ and in the Virgin who bore Him. Unfortunately, the present frame creates such a powerful shadow over the crucial few inches at the top of the painting that these important details are all but lost, save in high-res virtual images.

Rembrandt (1606-69), The Holy Family, 1646, Kassel, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Photo: courtesy Rijksmuseum

The Sistine Madonna is transformed by Rembrandt from the icon of the Marian cult to a 17th century Netherlandish working-class mother, caught in an intimate embrace with her child, in a mundane domestic setting which underlines the reality of Christ’s birth: Joseph the carpenter is chopping logs outside the door. The trompe l’oeil Auricular frame and curtain painted around the scene play with Raphael’s symbolic use of this trope; there is a single curtain which hangs ‘outside’ the lighted interior in the manner of a stage curtain drawn back across the proscenium arch. It is red (for the celebration of Christ’s Passion), and echoes His red costume, so the viewer is evidently meant to contemplate the future sacrifice of the Crucifixion; but then there is also the frame to be fitted into this pre-figuring.

Nicolaes Maes (1634-93), The Holy Family (after Rembrandt), c.1646-50, red chalk, blue chalk, brown & red wash on vellum, 22.8 x 27.9 cm., Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

It is only possible to consider the frame properly by turning to the copy by Nicolaes Maes of Rembrandt’s painting, made before it was cut down by some philistinical owner, and where the resemblance to a proscenium arch seems clear – or, perhaps, clear from the point of view of the present day. A more historically sympathetic way of looking at it might be to note the pilasters at the sides, the amorphous angels hovering along the arch, and the strange carved barrier of the sill, all of which may recall the idea of the entrance to the Holy of Holies in the Temple of Jerusalem. Rembrandt was friendly with a large number of the flourishing Jewish community in 17th century Amsterdam – his doctor was Jewish, he had Jewish clients, he painted events in the Old Testament, and even took care, in Moses breaking the tablets of the Law, to have the tablets inscribed in Aramaic script. This archaeological exactitude in the representation of Biblical scenes may well have extended to his memory of the description in Exodus of the Ark of the Covenant and its location:

‘And thou shalt make a vail of blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine twined linen of cunning work: with cherubims shall it be made:

And thou shalt hang it upon four pillars of shittim wood overlaid with gold: their hooks shall be of gold, upon the four sockets of silver.

And thou shalt hang up the vail under the taches, that thou mayest bring in thither within the vail the ark of the testimony: and the vail shall divide unto you between the holy place and the most holy.’ [9]

The frame may therefore be suggesting the pillars and veil of the Temple which protect the entrance to the Ark of the Covenant; so that its painted curtain contains the red element of the Old Testament curtain, as well as that of the Christian red hangings for the Passion, and the two pilasters stand in for the four pillars across the entrance. The angels in the arch are simultaneously the cherubim carved on the Ark itself, the cherubim embroidered on the Temple curtain, and the angels present at the Nativity. This is a much more developed and scripturally exact use of Old and New Testament parallels than Raphael’s. The curtain opens now, not onto the Ark of the Covenant of the Old Law, but onto the infant Christ, whose physical being is God’s covenant with the world under the New Law. The whole painting is, so to speak, a complicated pun or visual play on the transition from the Old Testament past to the New Testament future, all expressed through the contemporary means of a Netherlandish domestic scene within a fashionably contemporary Auricular frame. NB This is what happens when original frames are excised or changed: the meaning of the image can be radically altered, or lose a layer of significance.

Lenten coverings and curtains

Book of Hours of Frederick III, South Netherlands, 1475-1500, detail of f.9r, showing crucifix, statues and altarpiece covered in cloth or curtained for Lent in the late C15; © The British Library Board

The idea of the Temple curtain in Jerusalem had a much wider influence than Rembrandt’s very focused evocation of it. The theme of revelation, which included within it, of course, the opposite idea of concealment, was particularly appropriate for the forty days of Lent, from Ash Wednesday to Easter, when the Passion and Crucifixion would lead, through the concealment of the tomb, to Resurrection and revelation. Curtaining altarpieces, images and reliquaries from the gaze of the worshipper was in tune with the bodily deprivations of Lent, the removal of distractions from contemplation, and the remembrance of the Temple curtain before Christ’s death, barring access to God.

Like the frescos of curtains in early Christian churches and the hangings around altars, the use of Lenten curtains seems to have been in operation from an early point; in this case from at least the 7th century [10]. In the illustration above, from a 15th century Book of Hours, a white curtain passes right across the church behind the altar; another hangs from a wire or rail along the top of the altarpiece (of which the edge of the gilded frame is just visible); the matching riddell curtains are drawn forward on either side of the altar; and the carved crucifix above the altarpiece and flanking sculptures each has a tailor-made cover which reveals the contour of what it hides.

Pieter Brueghel the elder (1526/30-1569), The fight between Carnival and Lent, 1559, panel, 118 x 164 cm., detail with veiled statues inside a church, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Through the open doors of the church in Brueghel’s Fight between Carnival and Lent, statues can be seen which are also veiled in white – here, in bell-shaped pleated covers like elongated lampshades.

Lenten colours were different in France, where a 17th century work by Cardinal de Retz on Catholic ritual laid out the requirements of veiling the church for Lent, with all images, altarpieces, sculptures, reliquaries and processional crosses to be covered with ‘violet or ash-coloured veils made from camlet or damask silk’, and in particular:

‘…before the high altar, between the choir and the sanctuary, from one side to the other, a great oblong and wide veil is hung, or a large curtain made of violet or ash-coloured camlet, which can be drawn back or folded or let down when needful…’

This veil remains until the dramatic celebration of the Passion of Christ:

‘It is elevated in each part of the choir, and held by two clerics, until these words of the Passion: “And the veil of the temple was rent in the midst”. And when the deacon pronounces those words, at the command of the Master of Ceremonies, the two aforementioned clerics immediately let go, so the veil may suddenly fall entirely on the floor of the choir, and it is afterwards taken away by the sacristan.’ [11]

Konrad von Friesach (fl. c. 1440-60), Lenten veil, 1458, tempera on linen, 887 cm. square, Cathedral of Gurk, Carinthia, S. Austria

Although these curtains were usually made of plain white, grey or purple linen or silk, another regional custom developed of using painted or embroidered panels, joined together in vast patchwork depictions of the life and Passion of Christ, or a panorama of biblical scenes; they might also consist of one large painted scene within a border, like a tapestry . They could be hung directly onto or over an altarpiece, or be suspended from the chancel arch to hang in front of both altar and architectural altarpiece, the Lenten veil of Gurk being one of the older and larger survivals. It was originally made in two halves – like the curtain of the Sistine Madonna – to represent the Temple curtain, and is one of around forty veils in the Carinthian region of Austria. Each of the 99 paintings is bordered by a plain margin, in keeping with the ban on distractions from contemplation; it is like a great polyptych itself, and covers events from both the Old Testament (left-hand curtain) and New Testament (right-hand curtain), ending with a double panel of the Last Judgement [12].

Other Austrian veils have survived from the 15th and 16th centuries, including a fragment of two panels with decorative ‘frames’ in the Belvedere, Vienna. There are also German examples, such as the Great Zittau Lenten Veil of 1472 (820 x 680 cm.), now displayed in the Church of the Holy Cross in Zittau; but the Great Lenten Veil hung before the altar in Salisbury Cathedral must have vanished during the Reformation.

Teramo Piaggio (attrib.; Theramus de Zoaglio, fl. 1532-54) and others, The Passion of Christ, 1538 onwards, from a set of 14 painted pieces of Genoese indigo linen, the largest up to 500 x 350 cm., Abbazia di San Nicolò del Boschetto, now Museo Diocesano, Genoa

In Italy, the Lenten veil multiplied into whole pop-up monochrome chapels, one of which is kept in the Museo Diocesano of Genoa. It is painted in white on fourteen panels of the indigo cloth known in Italy as blu di Genova, and in France as cloth of Gênes (= jeans); the panels date from the 1530s to the late 17th century – although others are recorded as much as five hundred years earlier. The set includes a ceiling cloth, and some of the images are based on engravings of the Passion by Dürer and Marcantonio Raimondi.

‘The kiss of Judas’ from The Passion of Christ, 1538 onwards, Museo Diocesano, Genoa

‘The kiss of Judas’ from The Passion of Christ, 1538 onwards, Museo Diocesano, Genoa

These tented ‘chapels’ seem not to have been a purely regional, Genoese-based genre of Lenten cloths, in spite of the fabric of which they were made, since the Tuscan artist Cennino Cennini (c.1360-pre-1427) describes in Il libro dell’arte how to paint on blue hangings:

‘If you have to work on black or blue cloth, as for hangings, stretch your cloth as described above. You do not have to apply gesso… Take tailors’ chalk…put a little stick into [a goose-feather] quill, and draw lightly. Then fix with tempered white lead. Next, lay a coat of that size with which you temper the gesso on anconas or on panel. Then lay in as thoroughly as you can, and paint costumes, faces, mountains, buildings, and whatever appeals to you; and temper in the usual way.’ [13]

In effect, what was produced in this novel form was a portable New Testament inversion of the Holy of Holies, which could be set up during the season of Lent, concealing the normal decorative appearance of the church in which it was erected from the congregation inside the tent. The choice of blue monochrome is interesting; it is presumably dictated partly by reasons of economy and hard-wearing quality (blu di Genova was used to make trousers for sailors), and partly by a near approach to the ‘violet or ash-colour’ of French Lenten cloths.

A crucifix veiled, shown with Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, in an article from 2019

Altarpiece curtains

In his fascinating article on the various covers used for altarpieces in Lombardy, Professor Alessandro Nova notes of curtains that:

‘For altarpieces of a certain prestige, hangings were an integral part of their furnishing…’ [14]

going on to explain that,

‘…around the 11th century, with the intensification of the Marian cult, the hanging became the Virgin’s special attribute…’

and that

‘…the 15th century inventories of Siena Cathedral record that Duccio’s Maestà was once covered with a vermilion hanging. Filippino Lippi’s altarpiece for the Florentine Otto di Pratica … was protected by a blue hanging which when open was held back by white and red silk bows’ [15]

Book of Hours of Frederick III, South Netherlands, 1475-1500, detail of f.9r, © The British Library Board

Curtains specific to an individual altarpiece were thus historic accessories, even for the finialled extravagances of a Gothic polyptych, and – where the Lenten cloth was not a huge, chancel-filling sheet hung from an independent rail – some other means was needed to attach it, or other forms of curtain, to the smaller, dossal type of altar retable. From the 15th century, there is a number of altarpieces still in their original frames which retain the fixings for a curtain rail, and sometimes even the rail itself – drooping slightly from years of use, like the painted curtain rail in the Sistine Madonna.

Brabant School, Antependium of Christ with the instruments of the Passion, c.1480, oak panel, 93 x 193 cm., with detail of hook to hold a curtain rail, Museum of Leuven, Belgium

The Antependium of Christ in the Museum of Leuven is a painted wooden altar frontal, which may have been twinned with a matching dossal or reredos sitting on top of the altar at the back. It has a handsome inner gilt and polychrome moulding with a rainsill at the base, and a coarser, shaped outer architrave moulding, which appears to have been repaired at the bottom with a modern black-painted rail – probably to cope with the ravages of many priestly feet kicking it over the centuries.

At the top left-hand corner one of the hooks for the curtain rail still remains; there may have been a ring with a stop at the other end, into which the rail slotted, or another hook, on which the rail was laid. Since the frontal is painted with Christ, two angels and the figures of two donors, a full-length curtain may only have been used in Lent or on other penitential occasions, allowing the painting to be visible for much of the time. The cloth on the altar table above it would have covered just the top itself, possibly descending in the short valance known as a ‘frontlet’ to conceal the curtain rail, unlike full-length altar cloths where there was no painted frontal (see the illustration from a Book of Hours, above). The curtain may not have been drawn across or opened; it may have been simply a static piece of fabric, which was either installed or completely removed; it would have matched the curtains for the altarpiece or dossal above it, and those used for any sculptures.

Giovanni Bellini (c.1435-1516), Madonna & Child, c.1480-90, oil & tempera/panel, 90.8 x 64.8 cm., with the metal eyelets at the top of the frame used for mounting a curtain rod; National Gallery. Photo: with thanks to Peter Schade

The frame which has been used for this Bellini in the National Gallery is of the same general period as the Brabant frame, although it was made for a free-hanging panel or a dossal rather than an altar frontal. The rings which held the curtain rod at each end of the top rail have been restored, and could be used once more as a demonstration of a working liturgical curtain.

The Bellini may have had its own curtain/s when in its original frame, and the colour of the cloth of honour hanging down behind the Madonna suggests that this might have matched the default colour of a frame curtain or curtains – green would have been the colour most often in use – giving an extraordinary perspectival depth and reality to the space within the painting, by its apparent ‘continuation’ into the world of the worshipper. The combination of two real curtains drawn to each side of a painted Madonna and Child and a matching cloth of honour within the painting must have been a very frequent sight in the later centuries of the Marian cult. Together they would have created something of the same effect as a curtained ciborium, or an altar sheltered by a rear and two riddell curtains, with the figures of Christ and His mother once more analogous to the altar itself.

Cosimo Rosselli (1439-1507), Madonna and Child with SS Thomas & Augustine, paliotto by Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli (1450-1526), 1482, with detail of curtain rail, Santo Spirito, Florence

Still from the same period as the two frames above, there is a group of classicizing aedicular or all’antica altarpieces in Santo Spirito, Florence, the frames of which are supposed to have been designed by Brunelleschi (although not executed until four or more decades after his death, just as the church itself wasn’t completed until the 1490s); these also retain either hooks and rings or a whole sagging rail, a good example of which can be seen on Cosimo Rosselli’s Madonna and Child, above. With these works, the curtains would have fitted neatly over the picture panel, between the pilasters and entablature (perhaps the predella was left unmasked, being small; perhaps the curtain descended to the top of the altar). In contrast, the Brabant antependium would have been completely covered, like the altarpiece in the Book of Hours of Frederick III, above. Presumably the relative size of the Santo Spirito paintings also meant that there might be room for two curtains which could be drawn open symmetrically, echoing the rending in two of the Temple curtain.

After Brunelleschi’s death in 1446, the completion of Santo Spirito was left to the architect Antonio Manetti, and in 1489 the sacristy was added by Giuliano da Sangallo, who was also a designer and provider of church furnishings including altarpiece frames. Another of the group of all’antica altarpieces in the church was Botticelli’s Madonna and Child with SS John the Baptist and Evangelist of 1484-85 (the Bardi altarpiece), now in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie in a pastiche of its original frame. The painting is recorded as having been commissioned by the banker, Giovanni de’ Bardi, who ordered its frame from Sangallo, along with a stained-glass window, a curtain and a painted altar frontal or paliotto[16].

Raffaellino del Garbo (c.1466-1524), Madonna & Child & SS John the Evangelist, Lawrence, Stephen & Bernard, paliotto by Donnino (1460-post 1515) and Agnolo (1466-1513) di Domenico del Mazziere, St Lawrence, 1505, Cappella Segni, Santo Spirito, Florence

Most of these altarpieces in Santo Spirito are made in slight variations on the same all’ antica structure, of similar dimensions and with an almost identical arrangement of panels in the predella; they also share the same relationship of altar with painted frontal on a stepped dais, with a stained-glass window above and a curtain on the frame; and the frontals were all painted with similar designs in one of the same three workshops. This argues an unusually homogenous and integrated vision of the church’s interior, possibly forwarded by Sangallo himself, who was an enthusiastic adherent to Brunelleschi’s ideas; it also indicates that some, if not all, of the other frames, windows, curtains and frontals may have been ordered, like Bardi’s, through Sangallo.

The example above, by Raffaellino, includes curtains in the composition of both painting and paliotto. The traditional liturgical colours of hangings and vestments would probably have been maintained in this Medici church, otherwise it would be tempting to think that the default colour of the physical curtain/s made for this altarpiece could have been of the same golden yellow as the painted curtains held up by small angels, echoing too the golden flowers on the trompe l’oeil red brocade curtains of the frontal.

Jean Bourdichon (?1457-1521) and Ioan Todeschino (14**-1503?), Book Hours of Frederick III of Aragon, c.1501-02, executed in Touraine at the court of the exiled king of Naples; MS Lat 10532, f 199 and f 198, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

In this illuminated French/Italian MS, created for the last Aragonese king of Naples, gold is indeed used for the curtained altarpiece in the right-hand image. Gold could be used as a liturgical colour at Christmas and on Easter Sunday/Holy Week, but would not have been appropriate for Good Friday and for the Crucifixion. Similarly the brocade curtains covering the framed panel of text in the left-hand image seem far from liturgical in their pattern of blue and white sunflowers woven on gold (although their lining is the default green). This may be less a fanciful elaboration of the illustrations themselves than an acknowledgement that private chapels and domestic altarpieces might be curtained, not in the changing colours of the ecclesiastical season, but in colours more personal to the owners.

The posthumous inventory of the goods of Sébastien Zamet, made in Paris in 1614, may support this idea; it records two square paintings in inscribed ebony frames, one on panel of a sun wreathed in small angels, and the other on copper, with an eagle and a lion supporting a coat of arms. Both pictures have red damask curtains with an edging of gold lace, and the copper panel has a leather bag to store it in:

‘1 autre tableau peint sur bois garni de sa bordure d’ébène avec lettres d’or alentour représentant un soleil environné de petits anges, garni de son rideau de damas rouge avec dentelle d’or alentour, contenant 1 pied en carré ou environ tant de hauteur que de largeur… 6 [livres]

1 autre tableau peint sur cuivre enrichi de sa bordure d’ébène avec lettres d’or alentour et aussi garni de son rideau pareil à celui ci-dessus, représentant un aigle et un lion avec une devise dessus, contenant 1 pied ou environ tant de hauteur que de largeur, led[it] tableau dedans un étui de cuir…. 12 [livres]’[17].

The first is a sacred work (a symbol for God the Father or Christ in glory), and the second is a symbol of the status Zamet had achieved, and was presumably intended to be portable. Such small paintings only needed one curtain each, the colour of which may have been chosen to reflect other interior hangings or decorations, or to harmonize or contrast with the paintings. Although both were the same size (around a foot square), the copper panel was valued at twice the price of the wooden panel (12 livres, as against 6). Zamet also possessed an Ecce Homo only a little larger (1 ½ x 1 pieds), but this had no curtain attached to its giltwood frame.

He did, however, have another work which had a wooden cover:

‘1 petit tableau peint sur bois garni de sa bordure avec une couverture de bois, où est représenté une Assomption [de] Nôtre Dame, contenant 8 pouces de haut sur 6 pouces de large.’ [18]

Further to the very early covers mentioned in Part 1, the wooden frame with a groove for a fitted cover which could be pulled back and forth to reveal the image inside was part of a sort of small sub-genre of folding and shuttered works. Most have, over time, been separated from their covers, and many were for secular paintings – mostly portraits – and will be discussed in Part 3. Evidently, however, this method of protecting or hiding a picture applied as much to sacred as to other works (as it did to looking-glasses), and the entry in Zamet’s inventory confirms this. His Assumption of the Virgin was a very small painting on panel – only about 8 ½ inches or 22 cm. high – just a little larger than the ivory diptych illustrated in Part 1; not small enough to hold in the palm and meditate on, but small enough to take travelling: to lie on a chest in a strange bedroom or to prop on a cabinet in a distant office.

Sodoma (1477-1549), St Benedict absolves two dead nuns, from the Life of St Benedict, 1505-08, fresco cycle, with a detail showing the curtain on an altarpiece, Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore. Photo: Web Gallery of Art

In contrast to Zamet’s domestic ebony frames with their red curtains (presumably a personal choice), a properly liturgical red curtain appears in the rare sighting of a curtained altarpiece in a church interior, painted by Sodoma in the background of his cycle of frescos on the Life of St Benedict. The colour indicates that the events shown in the church take place during Passion Week. The altarpiece is a Gothic triptych with the silhouette of a basilica, barley sugar columns and finials; and the curtain, taking the easy path, avoids these hazards by shutting off the whole apse where the altar stands, in what would by then have been a rather old-fashioned arrangement but may be intended to evoke (loosely, to an age which had little archaeological grip on the past) the period when St Benedict (c.480-c.547) was alive.

There is little sense here that the Temple in Jerusalem is more than a distant metaphor, since there is only a single curtain, not a pair, even though the space is quite large and the symmetry of apse, altarpiece and St Benedict and his monks seem to require it. However, the stage-like organization of material and rail within the lighted apse must have added to the drama of revelation when the whole polyptych was discovered.

Pieter Jansz Saenredam (1597-1665), Cathedral of St Jans Kerk at ’s-Hertogenbosch, 1646, o/panel, 128.9 x 87 cm., National Gallery of Art, Washington

A hundred and forty years later, in the Netherlands, Saenredam painted a very different church interior. The choir here is also curved, but vast, pierced with arcades and windows, and the altarpiece is a massive free-standing Baroque construction of black, white and salami-coloured marble, with tiers of figures ascending into the airy segmental dome high above the painting. Interestingly, however, in the study that he produced for this work, where everything (save the height of the cathedral) is ready to act as a reference for a finished painting, Saenredam has painted exactly what he must have seen when visiting St Jans Kerk, with the Adoration of the shepherds covered by the default green curtain.

Pieter Jansz Saenredam (1597-1665), Choir and High Altar of St Jans Kerk at Bois-le-Duc, with figurative sculpture above, on the wall beyond two tablets inscribed with the dates ‘1598’ and ‘1621’ and with heraldic devices, 1632, pen & brown ink, grey wash & watercolour, over black chalk, 40 x 32 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Unlike the altarpieces in Santo Spirito, where the curtain rails are draped loosely across the lower mouldings of the entablature, this curtain hangs from a rail pushed up neatly to the base of the lintel, and fits over the whole face of the altarpiece painting. This is perhaps an even rarer depiction than the image of an altarpiece with an opened curtain, and yet it must have been a very common sight in churches for hundreds of years. There may well be two curtains, as this is a large altarpiece, and it is probable that they would have been opened on a running system of cords, operated from behind the columns.

Altarpiece blinds

There must, of course, have been many such mechanisms – including such simple ones as pulleys and cords – to operate the curtains over larger altarpieces, just as there were for the vanished portelli ot sportelli which were slid sideways or dropped down over the permanent paintings, and may have been confused with hinged shutters (see ‘Part 1: Covers and shutters on sacred works’). There seems to have been something similar for the Lenten curtains, especially as they aged, became more precious to their parish, and could no longer just be pulled down onto the floor.

The high altar of San Salvador, Venice (c.1534, designed by Guglielmo de’Grigi, il Bergamasco, c.1485-1550); view with the silver-gilt Pala d’argento, 1380/1400 and beginning of the 18th century; and with Titian’s Transfiguration (c.1560 o/c, 245 x 295 cm.) raised over it

And there are more striking, if just as practical, mechanical arrangements: for example, the Pala a’argento or Pala d’oro on the high altar of San Salvador in Venice has what can only be described as a blind installed inside the frame – a blind painted by Titian with a Transfiguration of Christ – which could be wound up over it from the altar beneath. The mechanism for this process is worked by a system of counterweights, according to Professor Alessandro Nova quoting R. Pallucchini[19], or, more simply ‘through a pulley system’, according to the Save Venice project [20].

The Pala d’argento or Pala d’oro of San Salvador. Photo: Didier Descouens

The Pala d’oro itself is only revealed during the periods of Christmas, the Easter week, and the feast of San Salvador (the Transfiguration) on 6th August. The oldest part of it is, itself, an antependium or frontal in the form of a shuttered tripych – although, very unusually, it is hinged on the long horizontal sides, the panel with a silver-gilt Transfiguration occupying the wide central band. It was presumably opened only for high festivals, when it would hang in front of the altar. It was extended with further panels at the top and bottom in the 16th century, becoming a fixed five-panelled polyptych and disappearing behind its protective ‘cover’ for most of the year.

Details of the high altar of San Salvador with Titian’s Transfiguration in place (after restoration), and then descending progressively downward into the altar

There is a fascinating film of Titian’s Tranfiguration descending from its fixed position into the altar, followed by close-up details of the revealed Pala d’oro, and then of the canvas being raised again to hide it: Ikon TV, ‘A wonder: the silver-gilt pala in the Church of San Salvador, Venice’. The Titian, although it was presumably not being lowered and raised much more often that is the case today, did suffer during its centuries of movement and was repainted in areas of wear; it has recently been restored by the Save Venice project. The figure of Christ on the crest of the frame was at one time also animated:

‘…the sandstone sculpture of Christ which crowns the altar (possibly a later addition) has a wooden arm, which at one time could be raised and lowered at the elbow by a pulley system guided from behind the altar, producing a special effect during the celebration of the mass.’ [21]

Part 1 of this trilogy of articles, in the discussion on shutters, looked – as mentioned above – at the movement of portelli over permanent large architectural altarpiece paintings in Italy, finding that at least some of them were much less likely to have possessed hinged shutters on what might be greatly elaborated aedicular frames than they were to have had painted canvas covers on battens which could be slid in front of them, via narrow openings and tracks inside the frames. They might also be slid out of their own frames, revealing something in the space behind.

G.B. Conti, San Gabriele, with details of the pulley system at the back of the altarpiece, Cappella di S. Gabriele dell’Addolorata, SS Giovanni e Paolo, Rome

This kind of system was revealed at San Giovanni e Paolo in Rome, thanks to the investigations of Marc O. Manser; he also discovered that there was a roller-blind-like mechanism fitted to at least one of the large altarpieces there, enabling a flat piece of fabric (like the Lenten curtains, or like a reversal of the San Salvador Titian) to be lowered by a pulley over the permanent painting. The photos above show the back wall of the altarpiece, with the ropes of the pulley visible beside the boxed-in canvas. This current arrangement probably dates from the 18th or 19th century, but was also likely to have been a common method of covering such large altarpieces during Lent since they first became widespread in the 15th-17th centuries. There is, as previously noted, a connection with the movement of theatrical flats and backdrops, especially for canvas-&-batten flats which slid on tracks:

‘Nicola Sabbatini’s (1574-1654) Manual for Constructing Theatrical Scenes and Machines, published in 1638, listed three main methods of changing scenery: one used periaktoi; the second manoeuvred new wings around those already there; and the third pulled painted canvas around the wings to conceal the previously visible surfaces. In addition, the author explains how to change the flat wings near the back of the stage by sliding them in grooves or turning them like pages in a book’ [22].

Inigo Jones (1573-1652), a very close contemporary of Sabbatini, ‘flew in scenery from above’ [23], in what must be a near approximation of the pulley system for veiling altarpieces; he also introduced the proscenium arch to Britain, with ‘a falling curtain’[24]. And, further back, a more general statement on ‘Stage machinery’ notes that,

‘…In the late 14th century Italian artists, architects, and engineers began to design elaborate machinery for spectacles produced in the churches on holy days. One such device was the Paradiso, a system of ropes and pulleys by which a whole chorus of angels was made to descend, singing, from a heaven of cotton clouds’ [25].

Anon., The construction of the Tower of Babel, c.1400-10, Rudolf Ems (fl. 1200-54) retelling of Old Testament story, MS. 33 (88.MP.70), fol.13, J. Paul Getty Museum

In these kinds of relationships, through spectacle, music, and painted images, the theatre (and later the opera) was closely linked to the Church – and both of them relied heavily on the types of machinery in use for straightforward building projects, where pulleys, winches and windlasses had been in common use since the classical period. Professor Nova, in his article on altarpiece hangings, curtains and shutters, quotes from a contract involving the Cremonese artist, Bernardino Campi:

‘In 1572 Bernardino Campi agreed to paint in oil a picture of the Mourning of the dead Christ for the monks of the Monastery of San Bartolomeo and also to buy cloth ‘di far la quartina’, a lapsus or spurious rendering of the word for curtain (cortina). On this covering, Campi painted a crucified Christ with Mary, St John, the Magdalen, and a kneeling monk — all done “in light and dark with a punched border around the edges and he also promises to have the beam and iron that goes at the bottom of the cloth made as well as the cord and strings to raise and lower said covering” (“di chiaro et scuro con il suo friso stampato a torno el ornamento e più promette di far far il subio et il ferro che va a basso alia tela et corde et cidrella da levar et bassar detta coperta”).

The beam (subio) is a wooden cylinder around which the cloth was wrapped; clearly this painted linen cover was raised up and down via the roller, which was set into action by the strings connected to it; while the iron bar held the cloth straight as the curtain was lowered to cover the altarpiece. In short, this was a system not unlike modern ‘roller-blinds’.” [26]

In his article, ‘Descent machinery in the playhouses’, John Astington mentions a flying Cupid in a performance of Gismond of Salerne in Greenwich in 1566, and notes that,

‘…The Revels Office accounts show constant expenditure on pulleys, ropes, cords, and wire for various kinds of effects…’ [27]

The theatre, as much as the Church, was a place where spectacle was the vehicle of revelation; and it is telling that the texts which describe Inigo Jones’s contributions to theatre and masque-making compare his proscenium arches to frames:

‘The stage which he used for the masques was set back behind the extreme ends of the side seats, and inclosed by an architectural or other border, much in the manner of the gigantic picture-frames which inclose the stages of modern theatres.’ [28]

The curtain as frame

Filippo Passarini (c.1638-98), Baroque curtain and cherub frame, probably for an image of the Madonna and Child, c.1680, Rome, 13.2 x 10.2 ins (33.5 x 26 cm.), Enrico Ceci Cornici Antiche, Modena. With thanks to Moana Weil-Curiel

Finally, in Filippo Passarini’s Baroque frame of the late 17th century, the protective curtains which have hung round the outside of altarpieces, formed part of the composition inside them, appeared as Lenten veils, and left traces behind them in the rails attached to frames, take the place of the frame itself [29]. It is carved (apparently in cypress wood) in the form of a single fringed golden curtain, looped and bunched at the upper corners, and tethered to the inner moulding by a pair of tasselled cords from which it escapes in a waterfall of folds and swags, in which painted cherubs hide. It is a very animated and dynamic curtain; it is swept to the left-hand side, as though by the winds of another dimension, and the cherubs may be trying to hold onto it and subdue it, rather than raise or close it. It is also punched in a decorative design, giving an effect analogous to the estofado techniques used in 17th century Spanish gilded polychrome sculptures for costumes, but here by means of the gilding alone.

Some of the cherubs harbour carved flowers – a strawberry flower for Christ’s Passion and a rose for the Virgin – indicating (along with the cherubs themselves) what the frame may have been designed for. It is upright, so it is meant for a portrait composition: probably either an Ecce Homo or a Madonna and Child; the second is more likely, because of the presence of the Virgin’s rose at the base. The movement of the fabric must be meant to suggest the agitation of the Temple curtain, before it is ripped in half by the death of Christ; and thus the painting and frame together would have stood for the beginning and the end of His life, the end of the old Covenant and beginning of the new, and the access His death gives for all humanity to the Holy of Holies beyond the curtain.

*********************************************

With particular thanks to Bruno Hochart, for the entries from Sébastien Zamet’s posthumous inventory, and to Marc O. Manser, for the photos and information on the moving altarpieces of SS Giovanni e Paolo.

*********************************************

[1] See the entry on the curtain (velum) in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1875, pp. 1185-86

[2] Pausanias (c.110-80), Description of Greece, book 5, ch. 12, s. 4

[3] Josephus, The Jewish war, or the history of the destruction of Jerusalem, 78 AD, Bk V, ch. 5, section 4

[4] King James Bible, Matthew, 27: 50-51

[5] See the mosaic detail from the 6th century basilica in Poreč, Croatia, of Bishop Eufrasius holding a model of the church with an open curtain across the door; illustrated in Eunice Maguire, ‘Curtains at the threshold: how they hung and how they performed’, in Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection, ed. Gudrun Bühl and Elizabeth Dospěl Williams (Washington, DC, 2019)

[6] Dr Beth Harris and Dr Steven Zucker ‘Santa Maria Antiqua’ in Smarthistory, 25 January 2017, accessed 1 November 2021

[7] Various churches may have slightly different colour/date combinations

[8] Johann Konrad Eberlein, ‘The curtain in Raphael’s Sistine Madonna’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 65, no 1, March 1983, pp. 66-68

[9] King James Bible, Exodus, 26: 31-33

[10] Gregor Kollmorgen, ‘Lenten veils’, Movement Liturgicus, 2 March 2012

[11] Jean-François-Paul de Gondi, Cardinal de Retz, Caeremoniale Parisiense, 1662, translated in ‘The Lenten veil (velum quadragesimale’, Liturgical Arts Journal, 9 March 2018

[12] See the website of the Katholische Kirche Osterreich

[13] Cennino Cennini, Il libro dell’arte, c. 1390s, translated by D.V. Thompson as The craftsman’s handbook in 1933, republished by Dover Books in 1960, p. 104

[14] Alessandro Nova, ‘Hangings, curtains and shutters of 16th century Lombard altarpieces’, in Italian altarpieces 1250-1550: Function & design, ed. Eve Borsook & Fiorella Gioffredi, 1994, p. 179

[15] Ibid., p. 181

[16] Antonio Fondaras, Decorating the House of Wisdom: four altarpieces from thew church of Santo Spirito in Florence (1485-1500), doctoral thesis, University of Maryland, 2011, p. 72, note 216, quoting the Libro di Entrata e Uscita di Giovani D’Agnolo de’ Bardi, segnato B, C Bardi MS. 9, 1484–87, Archivio Guiccardini, Florence, published in Igino Benvenuto Supino, Sandro Botticelli, 1900, Florence, p. 83

[17] With thanks to Bruno Hochart for so kindly sharing his copy of this inventory, ‘made after the death of Sébastien Zamet, Seigneur and Baron de Murat and Billy, member of the Royal Council and Privy Council, Master and Superintendent of the Royal works at Fontainebleau, at the request of his son, Jean’; Archives nationales, Minutier central: XIX, 381, 13 August 1614. Zamet was originally from Lucca, took French nationality, and became a millionaire financier in the orbit of the courts of Henri III and Henri IV. A portrait of his wife, attributed to Francois Clouet, was sold by Tajan in June 2005

[18] Ibid.

[19] Alessandro Nova, op. cit., pp.182-83; R. R. Pallucchini, Tiziano, Florence, 1969, i, p.310

[20] Quote from the Save Venice project on Titian’s Tranfiguration

[21] Quote from the Save Venice project on the San Salvador high altar

[22] See ‘Developments in staging’ in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. ‘Periaktoi’ are ‘large devices shaped like a prism with a different scene on each of the three sides… [which] were used in place of angled wings to achieve some of the earliest set changes’

[23] See ‘The story of theatre’ on the V & A website

[24] ‘Influence of technical achievements’ in Theatre, Encyclopaedia Britannica

[25] Ibid., ‘Stage machinery’

[26] Alessandro Nova, op. cit., pp.182-83, quoting R. Miller, ‘Regesto dei documenti’, in I Campi e la cultura artistica cremonese del Cinquecento, exh. cat., Milan, 1985, p. 468, note 217 (9 October 1572)

[27] Ibid., p.120

[28] Reginald Blomfield, A short history of Renaissance architecture in England 1500-1800, 1907, p. 74

[29] In Passarini’s Nuove inventioni d’ornamenti d’architettura e d’intagli diversi…, 1698, he has included designs which play with curtains as part of trompe l’oeil designs for, e.g, a basin holding a tabernacle, a tabernacle on a pedestal, a pulpit

In a time when travel is limited and museum attendance is a challenge, I’m especially grateful to this blog for showing me wonderful things that I’d probably never stumble across (on the internet) otherwise. It’s such amazingly high quality content.

I don’t often comment because I don’t really have much to add to the conversation but this Omicron variant looks like it’ll be stretching this “down time” out even further, so I’d like to say thanks to the blog and it’s contributors for making things a bit more bearable.

Stay safe,

Paul

LikeLike