The longest walk

Election battleground: Enniskillen

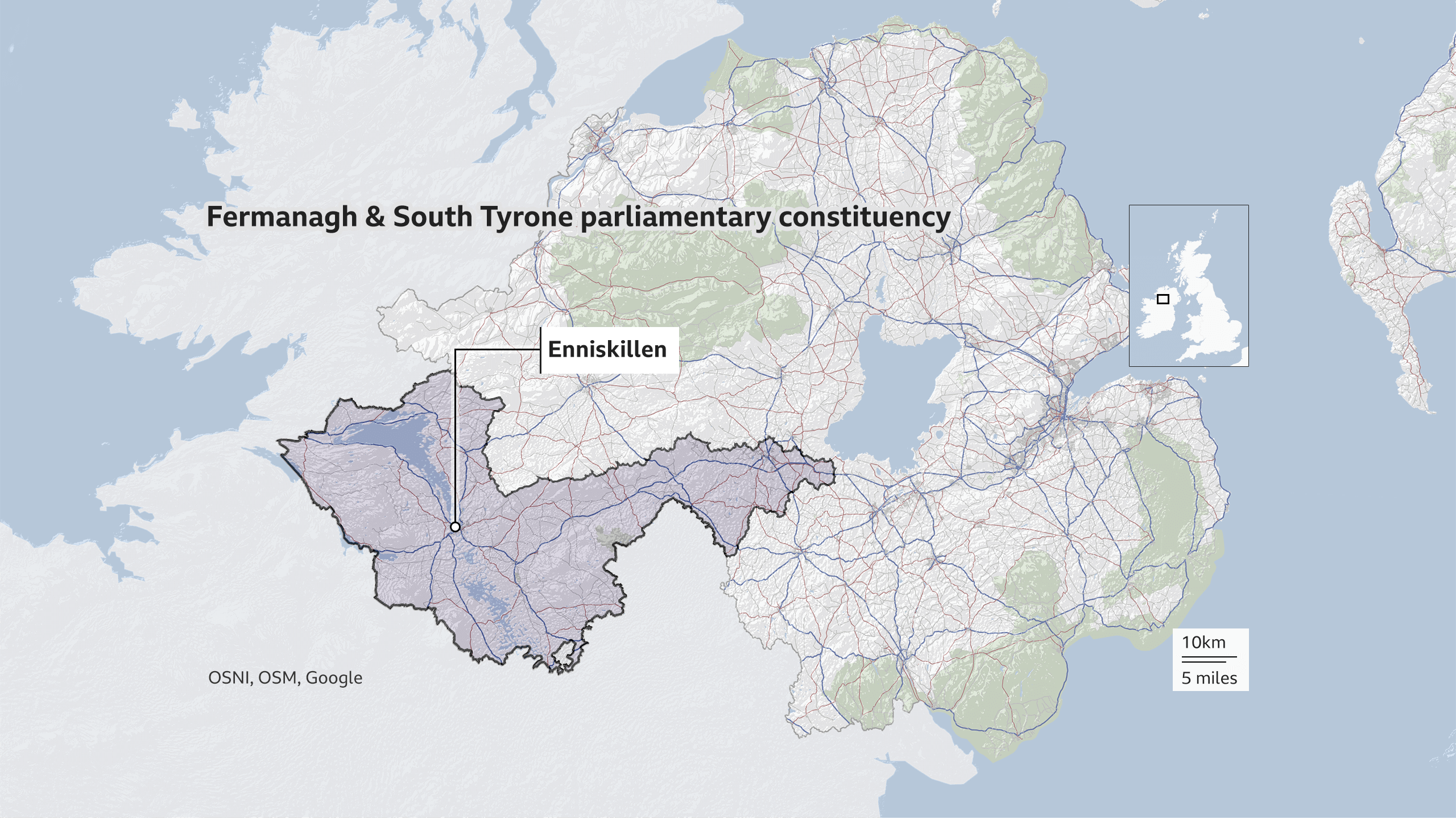

As politicians campaign for votes, we are looking closely at the places where the election could be won or lost. The town of Enniskillen - just a few miles from the UK-Irish border - is in the constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone, which is typically among Northern Ireland’s closest-run contests. However, one man there is trying to break the deadlock between the parties.

By Jon Kelly

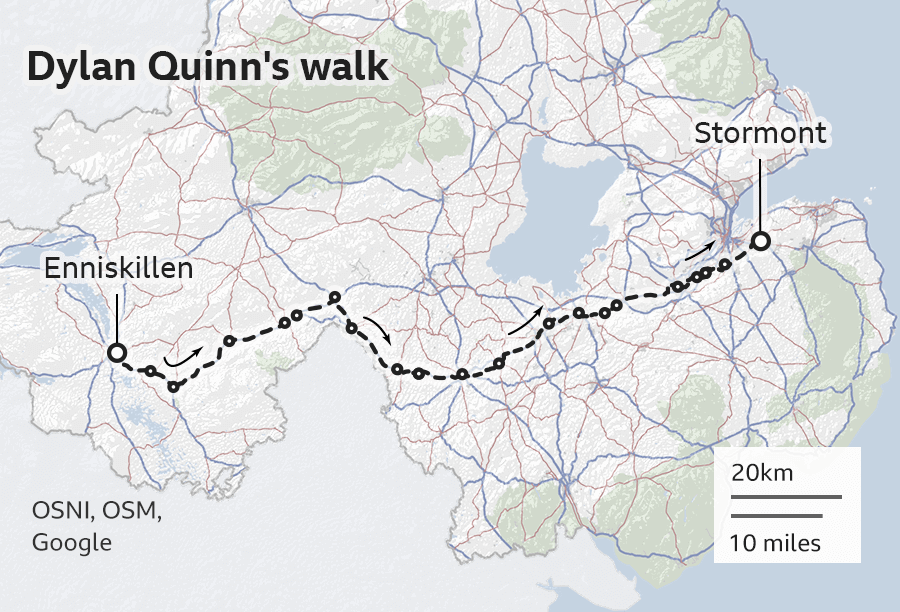

Dylan Quinn pulled on his walking boots and stepped outside. It was a clear morning and the sun had just risen over his hometown of Enniskillen, Co Fermanagh. He was setting off on foot to the Parliament Buildings in Stormont, a distance of approximately 90 miles - one for every member of the Northern Ireland Assembly who wasn’t currently taking their seat.

This was January 2019, almost two years since the devolved Assembly had collapsed in the wake of a scandal over a flawed green energy scheme. While the chamber sat empty, politics hadn’t stopped mattering to people and their communities.

In Enniskillen, there were still potholes in the roads and complaints of a staffing crisis at the local hospital. And most significantly, the border with the Republic of Ireland, one of the most contentious sticking points in the row over Brexit, was only 10 miles (16km) away.

And so as the months had gone by, Dylan felt a growing sense of exasperation and disbelief. He’d grown up in a town that had suffered badly during the Troubles - the 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland that began in the late 1960s. He remembered checkpoints at the borders and soldiers on the streets.

The power-sharing deal that had brought devolution back to Northern Ireland had been the outcome of a long and delicate peace process agreed by the British and Irish governments, and unionist and nationalist leaders. Now he and his wife were raising four children just outside Enniskillen. Why on earth, he wondered, were their futures being put at risk?

A wiry, fast-talking 45-year-old who runs a dance theatre in the town, Dylan thought hard about how he could express his frustration. Then the idea came to him. “I think walking is a very good, peaceful, non-threatening protest action,” he says. “It was about saying to people, ‘This is actually something quite simple.’”

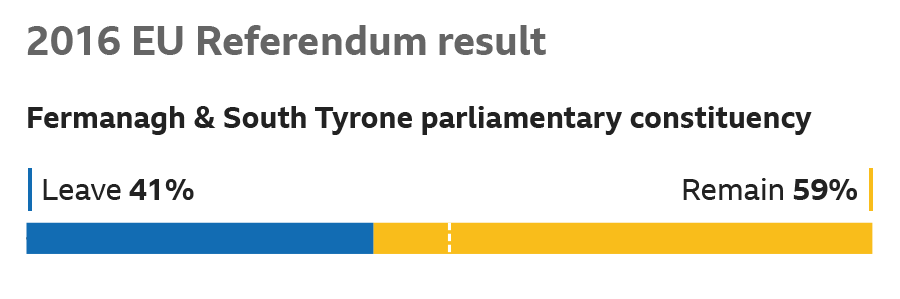

Enniskillen was a highly symbolic place to start. Built on an island, the town straddles the Upper and Lower sections of Lough Erne, its grand Georgian streets surrounded by a network of lakes, marshes and woodland. It sits within the Fermanagh and South Tyrone constituency, Westminster’s most westerly seat, at the very edge of the Union. The area’s carefully balanced demographics mean that at recent elections it has swung between nationalist and unionist candidates by the tightest of margins.

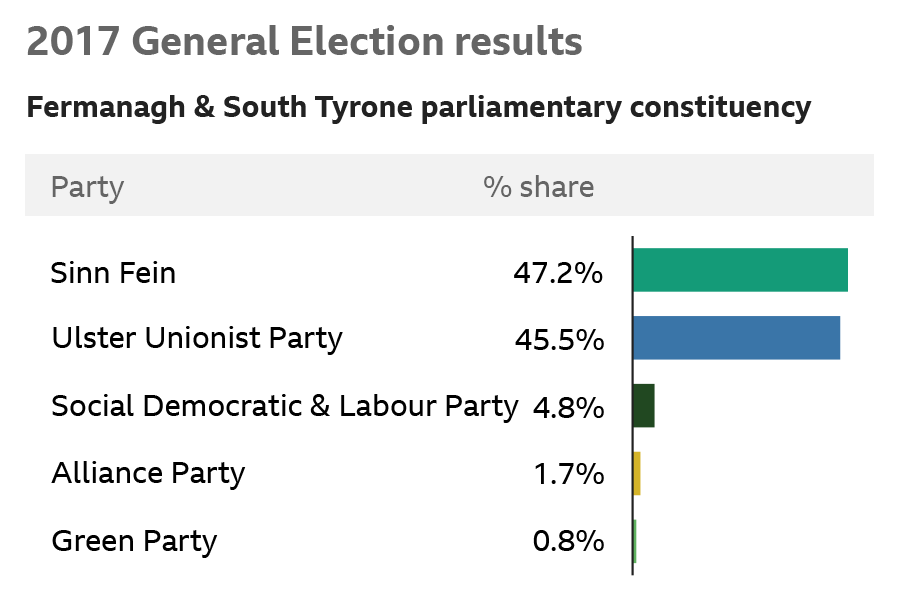

In 2017, Sinn Fein’s Michelle Gildernew won by 875 votes over former Ulster Unionist Party leader Tom Elliott. The Democratic Unionist Party hasn’t stood in the Westminster seat since 2005 so as not to split the unionist vote. However, DUP leader Arlene Foster, an Enniskillen native, represents the area in the Assembly.

In 2015, Elliott won by 530. In 2010, Gildernew edged out another unionist unity candidate by just four.

Dylan planned his route carefully.

It would take him three days. He’d aim first for the village of Ballygawley in Co Tyrone, rest there for the night, then push on to Portadown, Co Armagh. On the third morning he’d aim towards Belfast. He posted his itinerary on Facebook and invited well-wishers to join him.

His journey turned out to be more arduous than he expected.

In 1984, Dylan was at a junior swimming club in Enniskillen’s leisure centre looking out the window when a crack suddenly appeared in it. Four off-duty soldiers who had just returned from a fishing trip had been the target of a booby trap set by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Three and a half years later, in the front room of his home in the mostly nationalist Hillview estate, Dylan felt a sudden surge of pressure around him. Then he heard a blast and, through the window, saw a puff of smoke forming across the town.

An IRA device had gone off at a Remembrance Day parade, killing 11 people.

Back then, the Troubles were an inescapable presence. “You were not just aware of it, it was all around you,” Dylan recalls. In 1981, IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands was elected MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone - a hugely significant event in terms of the republican movement’s shift towards electoral politics. Then as now, the very closeness of the result made everything “a green or an orange issue” - that is, seen through the prism of nationalist versus unionist.

But there was more to life besides politics and sectarian divisions. “In the community, we kind of got on with things,” Dylan says. As a rural area, Fermanagh wasn’t segregated in the same way that a city like Belfast might be. His parents - his father was a chef and a musician, his mother a dinner lady and cleaner - were both from big families and were well-known across Enniskillen, with friends on both sides of the sectarian divide.

The classroom was one area where Catholics and Protestants didn’t mix much. But at one point Dylan had to go to drama lessons at a different school from his own, one attended overwhelmingly by pupils from Protestant families. His uniform marked him out as a Catholic. One day, as he was leaving the high school with his cousin, a group surrounded them and jostled them as they walked.

Then out of the corner of his eye he saw a much bigger boy charging across the road towards him. His uniform identified him as a Protestant. “And I thought, that’s it, we’re done for, we’re not fighters,” says Dylan.

But Dylan was wrong. The larger boy pushed the tormentors away from him and his cousin, and walked them to the end of the road and safety. “I remember thinking, ‘OK, not everybody is as you would think,’” says Dylan.

It was a turning point for him. “And those sorts of things were a key factor in me thinking, ‘Actually, things can change here, but it’s going to be a slow process.’”

Battlegrounds

As a trained dancer, Dylan had always thought of himself as relatively fit and healthy. But he wasn’t used to walking these kind of distances, not continuously, not for seven or eight hours at a time.

“It was much harder in the legs and feet than I expected it to be,” he says. At one point he got lost, and had to turn back, adding 10 miles to the journey.

But people were coming along to join him. Dylan couldn’t keep track of how many there were. Some strolled only short distances, others stayed with him to the end.

They told him why they’d come along - because they’d been on a hospital waiting list for years, or because their children’s schools had asked them to donate toilet paper and hand wash, and nothing was being done about any of this in the absence of a government.

Some said they didn’t feel there was a future in Northern Ireland for their children and grandchildren - they believed nothing would improve while the deadlock continued. Others said they were considering leaving themselves.

This point hit home with Dylan. Out of five siblings, he was the only one still living in Northern Ireland. He’d left himself at 18 to train as a dancer, working for years in England and further afield, before moving back to Fermanagh when his eldest son was born.

Victoria Graham also noticed an exodus from Northern Ireland. Most of her school friends left the country to study - only two have come back. But Victoria stayed put. She met her husband at 18 and, although she was offered a university place, decided to remain with him and get married.

Now 35, Victoria doesn’t regret her decision - she loves the area’s abundant natural beauty and believes it’s the perfect place to raise her daughter. She’s studying for a degree with the Open University. But at times, she feels isolated. “It’s been hard in terms of having a social group,” she says.

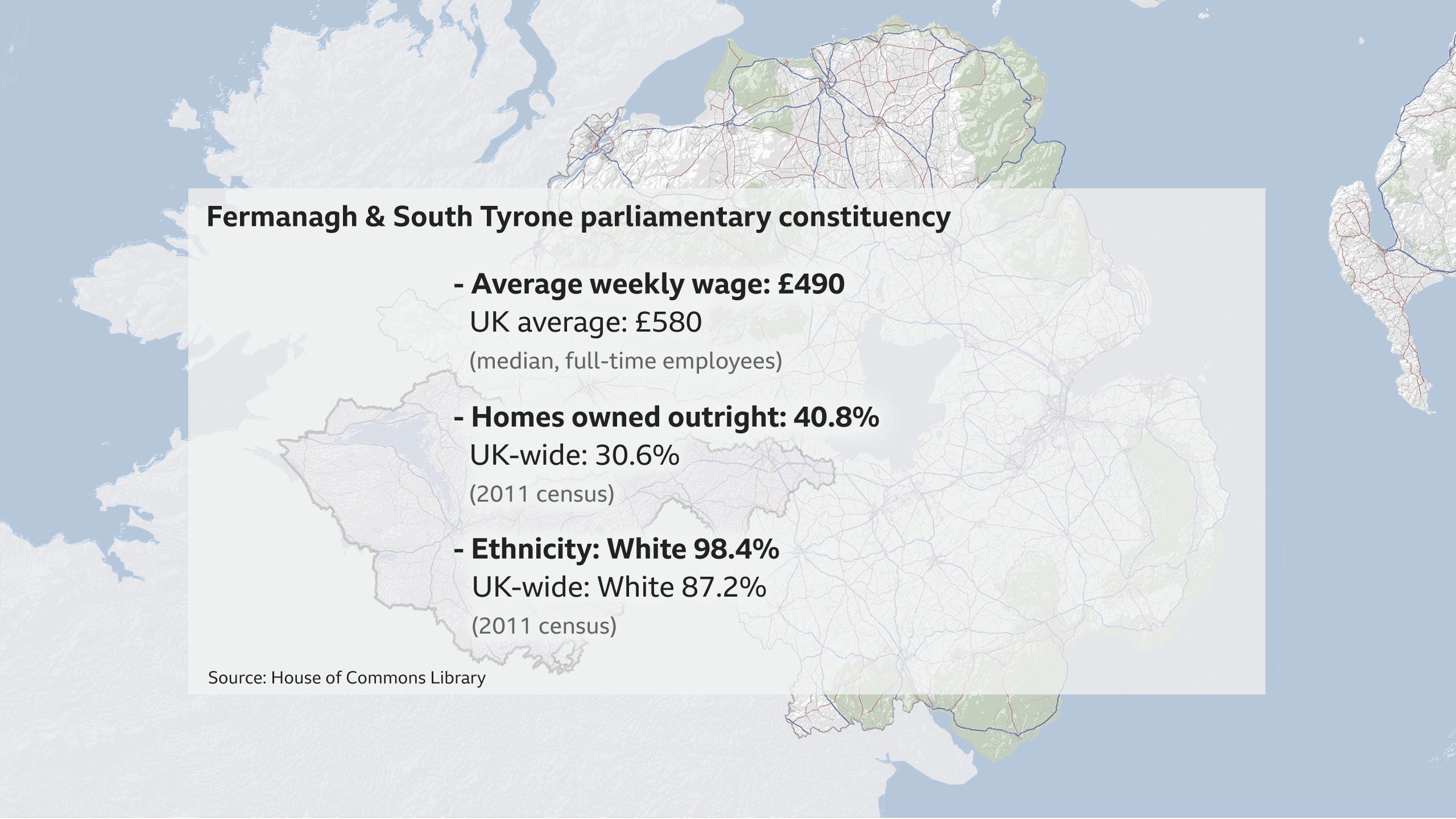

While Belfast has enjoyed a visible so-called “peace dividend”, with its refurbished Victorian buildings and revitalised former docklands, Fermanagh sometimes feels forgotten, she says. And the collapse of the Assembly has made that worse, Victoria believes - the absence of a government means there are no local ministers to take decisions to address its lack of rural public transport or its low-wage economy.

Still, she knows how much has improved since she was growing up. She remembers asking her father, a police officer, why he had to check underneath the car before the family could travel anywhere, and why he had to bring his gun with him to church. He was on duty nearby when the Remembrance Day bomb went off and witnessed the carnage first hand, pulling victims from the rubble.

Victoria knows Fermanagh has come a long way since those days.

“On the surface, everything is peaceful here,” she says. “And it’s lovely that everybody gets along and that there’s peace, it’s fantastic. But when elections come and the posters start going up… There’s an underlying tension, shall we say.” And often in such a closely fought race, she believes, the desire not to let the other side triumph often proves the strongest motivating factor: “It’s not what you’re voting for, it’s what you’re voting against.”

When Dylan set off from Portadown on the final morning, it was still dark. A man turned up clutching an energy drink. He’d just come off a nightshift. Dylan asked him: “Are you walking with me a bit?”

The man replied: “I’m coming all the way to Stormont.”

This wasn’t the first time Dylan had organised a protest about the lack of devolution. The previous August, when Northern Ireland was poised to pass Belgium’s record as the peacetime democracy that had gone longest without a government, he’d posted a video on Facebook calling for people to demonstrate. That had led to 14 rallies under the We Deserve Better banner.

The Assembly’s suspension meant it was left to Westminster to legislate on Northern Ireland’s behalf on divisive issues like abortion and same-sex marriage.

For campaigners who supported change, this was a welcome intervention - but those who opposed it reacted with fury.

Other issues fell by the wayside. For example, when Parliament was dissolved in November for the election, it in effect slammed the brakes on a Westminster domestic abuse bill. This included a provision to make coercive control an offence for the first time in Northern Ireland, bringing it into line with the rest of the UK.

Dylan doesn’t blame any one single factor for the impasse. But as well as a failure of political leadership, Dylan believes the absence of a peace and reconciliation process has prevented Northern Irish politics from moving on from the past. “We still have people who, rightfully and understandably, feel hurt and traumatised by their experience, but there’s no process for them to go through that, there’s no process for accountability. We’re not going to be able to get over that until that’s dealt with.”

Shauna Gallagher’s childhood was very different from Dylan’s and Victoria’s. She was born in 1988, on a farm near Irvinestown, a few miles outside Enniskillen. She doesn’t ever remember seeing any checkpoints.

With the peace process unfolding, her parents consciously brought her up to treat everyone the same regardless of their religion. She was 15 before she realised she had a recognisably Catholic name.

As a child she loved the freedom she had on the farm. But as she grew older she felt restricted by it. “I found being a teenager really difficult,” she says. It became harder when she was affected badly by acne. “It does really affect your confidence,” she says. “Unconsciously, I always wore my hair down so it was around my face. I’d always wear a thick layer of makeup.”

The skincare products she bought from the shops didn’t help much. So she took a beauty therapy course and started making her own natural cleansers, moisturisers and toners in her parents’ kitchen. “I thought: ‘It can’t be that hard, I’ll do it myself,’” she says.

It worked. Her acne cleared up. For the first time, people started complimenting her on her complexion: “God Shauna, your skin looks great.” They’d ask which products she was using and could they buy a pot?

So she decided to set up her own business. She learned everything there was to know about cosmetics - not just how to make them, that was the simple part, but also all the regulations and legislation she needed to follow. There was a setback when she found the name she had chosen for her business had already been trademarked by a major manufacturer - “I cried for about a week” - but soon she found her own premises, with a shop at the front and a small space to make up the products herself by hand.

She moved in not long before the Brexit vote. As well as selling online and to stockists around Northern Ireland, she began supplying shops across the Irish Sea in Great Britain too. There were also opportunities in the Republic, but - although it was only a few miles away - she thought it was safer to concentrate on the UK market.

What if there was a hard border? What if post-Brexit UK adopted different regulations and standards from the EU? It was too big a risk.

And then in October this year, the prime minister returned from Brussels with his latest deal. Legally the whole of the UK, including Northern Ireland, would leave the Customs Union. But in practice there wouldn’t be checks on the border with the Republic - in effect, the customs border would be in the Irish Sea.

Now Shauna sees the decision not to go after the market in the Republic as a missed opportunity. “I thought: ‘Why would I build these relationships and then maybe stop or maybe have to double the price?’ So it’s held my business back in terms of growth.”

Shauna blames Brexit for creating this uncertainty. She fears the new customs arrangements will mean extra red tape when she does business in Great Britain – the government has insisted it won’t, but there is still a lack of clarity about what it will mean in practice for businesses in Northern Ireland.

A few miles away, in the tiny village of Monea, Suzanne Livingstone, 52, isn’t worrying. Suzanne was raised and started a family of her own in Belfast. But she and her husband always used to take their holidays in Fermanagh. In 2001, feeling burned out by the pace of city life, they decided to move there permanently.

They set up a business from their house, selling home-made jam, marmalade, chutneys and pottery. Mostly they supply gift shops and cafes around Northern Ireland itself. She wants the Assembly to get back to work and thinks it needs to do more to promote tourism in Fermanagh. But the prospect of Brexit doesn’t trouble her too much.

“Everybody’s still going to get up in the morning,” she says. “We’re all going to go to work. We’re still going to need to eat and to do all the basic things of human life.”

The warnings about Brexit remind her of the year 2000, when there were fears that the Millennium Bug would cause aeroplanes to fall from the sky.

“On 1 January, we got up and life went on as normal,” she says. She thinks it will be the same this time: “Life will go on.”

“By the time I got to Belfast,” recalls Dylan, “my feet were bad.”

It hadn’t been so onerous on country roads. Now, as he neared the city, there were kerbs to go up and down. But there were more people with him, too.

He reached Stormont earlier than he had expected. Beyond the looming statue of Lord Carson, a former unionist leader, he could see the columns of the Parliament Buildings, the edifice’s classical grandeur an ironic counterpoint to the lack of activity inside.

Now he was right in front of Stormont. There were camera crews. People were taking his photo. He was asked to speak and he did, but making it about him hadn’t been the point.

He wasn’t under any illusions that his walk had changed much. He was still worried about where things were heading. “We’re a very naive democracy in Northern Ireland, a very young democracy. And to play with that is very dangerous,” he says.

“I don’t know what that answer is but all I can do is try to continue to do something. A little something. In the hope that all the little things I do will maybe join in with what other people do. And we’ll end up moving along in the right direction.”

Dylan’s wife and children had come to meet him and drive him back home. When they reached the car, Dylan lowered himself into the passenger seat. The lower half of his body ached and all he wanted to do was lie down - to put his legs in the air, feel the tension drain from his limbs. But there wasn’t space to do that, not in a small vehicle heading south-west in the dark towards Enniskillen.

He knew there was a long road ahead, for him, his hometown, and the rest of Northern Ireland.

Click here for a full list of general election 2019 candidates standing in the Fermanagh and South Tyrone constituency