From trees to trenches: Why Paul Nash was the most important landscape painter since Constable

26 October 2016

Renowned for his depictions of the First and Second World Wars, a major new exhibition at Tate Britain surveys Paul Nash’s entire career, from his earliest drawings through to his final visionary landscapes. WILLIAM COOK takes a closer look at this pioneering artist.

“My love of the monstrous and magical led me beyond the confines of natural appearances into unreal worlds,” wrote Paul Nash. Here at Tate Britain his monstrous and magical paintings are displayed in all their splendour, side by side.

In one room, you’re soothed by his serene landscapes. In another room, you’re shaken by his bleak depictions of the Western Front.

No artist since Constable had such a profound affinity with the English countryside

The two World Wars were the bookends of Paul Nash’s life. When the First World War began he was just 25, just beginning his career as an artist. When the Second World War began he was already crippled by the asthma that would kill him.

He died in 1946, just a year after VE Day. The pictures he left behind redefined landscape painting. No artist since Constable had such a profound affinity with the English countryside.

Nash acquired his deep love of nature as a child. His father was a wealthy barrister, and the family lived in a big house with a big garden in a pretty village in the Chilterns. Yet there was nothing sentimental about Nash’s early drawings of woods and meadows.

His parents had moved here to try and alleviate his mother’s mental illness. She died in a mental institution when Nash was 20, and his youthful pastorals are imbued with uneasy melancholy.

“I tried to paint trees as though they were human beings,” he recalled. People were absent from his paintings, but his trees are full of life.

When war broke out Nash joined up and was sent to the Western Front. He fell into a trench and broke a rib and was sent back to Blighty. In his absence, his regiment was wiped out at the Battle of Passchendaele.

Nash returned to the trenches as a war artist, filled with a fierce sense of mission - not to avenge his fallen comrades, but to portray the futility of war.

“I am a messenger who will bring back word from men fighting to those who want the war to last forever,” he told his young wife, Margaret. “No pen or drawing can convey this country.”

Nash’s art was saved from academic introspection by the outbreak of the Second World War

Yet somehow he succeeded. The result was We Are Making a New World, the greatest artwork of the ‘war to end all wars’. There were no corpses in this painting, only the shattered stumps of lifeless trees.

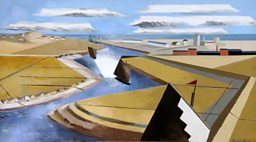

Nash returned home a man adrift, ‘a war artist without a war’. He suffered a nervous breakdown, but it was now that he produced some of his finest landscape paintings – lonely and desolate, but magnificent all the same.

He captured the windswept splendour of the English coast and the subtle beauty of its hinterland – not the dramatic terrain of Northern England, but the tamer contours of the Home Counties.

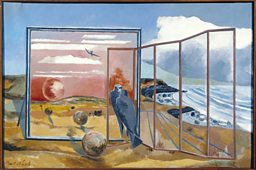

During the 1930s, Nash became increasingly interested in Surrealism. He helped to stage the International Surrealism Exhibition in London in 1936, a landmark show which introduced foreign artists like Andre Breton and Man Ray to Britain.

Yet compared with Continental masters like Max Ernst, his Surrealist pictures seem rather stilted. There was an element of Surrealism in all his work, but his best paintings were rooted in the real world.

Nash’s art was saved from academic introspection by the outbreak of the Second World War. Too unwell to venture abroad, he was employed by the Air Ministry to depict the battle in the skies above. It was a challenge he embraced with relish.

“When the war came, suddenly the sky was upon us all like a huge hawk hovering, threatening,” he wrote, poetically. “Everyone was searching the sky, waiting for some terror to fall.

“I was hunting the sky for what I most dreaded in my own imagining. It was a white flower - the rose of death, the name the Spaniards gave to the parachute.”

Unlike the wintry scenes of the 1920s, his late landscapes are ablaze with colour

Nash’s Battle of Britain paintings were a world away from his pictures of the trenches, but they were just as powerful.

He painted the wreckage of German planes, reminiscent of his sketches of shattered tree stumps on the Western Front (“by moonlight, one could swear they began to move and twist and turn as they did in the air”).

He painted a vast heap of wreckage, and gave it the title Totes Meer (Dead Sea), after Das Eismeer (The Sea of Ice) by the German artist Caspar David Friedrich.

“A vast tide moving across the fields, the breakers rearing up and crashing on the plain,” he wrote, of his creation. “It is not water or even ice, it is something static and dead.”

Plagued by ill health, and mindful that his death was imminent, you might expect Nash’s final paintings to be grim and morbid. However the last few pictures in this show are triumphantly alive. Unlike the wintry scenes of the 1920s, his late landscapes are ablaze with colour – an uplifting ending to this moving and invigorating exhibition.

Curator Emma Chambers and her team have assembled a wonderful array of Nash’s work, from rediscovered curios like Moon Aviary (a geometric sculpture lost for 70 years) to masterpieces like The Menin Road.

Remarkably, this is the Tate’s first Paul Nash retrospective for over 40 years. It’s been worth the wait.

Paul Nash is at Tate Britain from 26 October 2016 to 5 March 2017.

Bringing Nash's dreams from graphic novel to stage

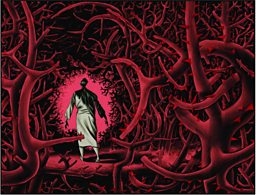

Alongside the exhibition, Tate Britain is also hosting a multimedia performance of Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash - a live staging of Dave McKean’s new graphic novel which explores the life of the war artist.

McKean – a giant of the comics world who’s best known for his covers for Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series – was approached by 14–18 NOW, the UK’s arts programme for the First World War centenary, to produce a work inspired by the conflict.

“The thing I was interested in was not the scale of the war, it was imagining one person going through that experience,” he says. “I wanted to look at the mind of a creative person, partly because – whether they talk about it or not – it’s in the work, there’s no escaping it.

“So I chose a painter, and I chose Paul Nash because of all the artists working in the First World War he came back with the strongest, angriest, most symbolic images.”

When it came to turning the book into a live performance, McKean – an accomplished pianist and composer as well as a writer and artist – opted for an approach he’d previously used on 9 Lives, a commission for the Sydney Opera House: “A sequence of stories, with film, synced to a live music performance.”

“I play piano and perform the narration,” he explains, “and a friend of mine, Matthew Sharp, is a world-class cellist and a great singer, so he sings the songs and takes the cello line. My wife plays the violin, and there are a few lines for Nash’s wife, so she does those.”

He adds: “As I was writing it – partly because Nash used to write little pieces of poetry inspired by William Blake – I started writing some of it in a poetic style.

“There were some rhyme schemes, which became lyrics, and it evolved into a sequence of seven songs, and an hour’s worth of music, synced to a film of the book.

“I don’t know what it is – it’s not really theatre, and it’s not just a reading of the book. It’s a more immersive version of it all, and I think the music really helps.”

Black Dog was commissioned by the Lakes International Comic Art Festival and 14–18 NOW. The performance takes place on Sunday 13 November. You can watch an extended interview with McKean on the BBC Arts Facebook page.

Related links

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms