Fraser Magnolia Trees: Ancient Botanical Relics

by Linda Martinson Blue Ridge Naturalist

Every year in May, the big magnolia tree behind our house in the woods surprises us almost overnight with several stately blossoms glowing like candles against large dark green leaves. Our tree is a Fraser Magnolia (Magnolia fraseri), sometimes called a mountain magnolia, and it is native to the Southern Appalachians where it is fairly common. The flowers are large, fragrant, and showy, and the leaves are also big (12 inches or more in length), tough, and dark green. They are deciduous trees, and the leaves turn yellow and drop in the fall, when they also glow in the sun. The tree is named for John Fraser (1750-1811), who was a Scottish botanist—one of the many botanical explorers who combed the New World for interesting plants and trees to send back to Europe.

There are 130 species of the genus magnolia, but only 8 of the species are native to the United States. Six of these species can be found in the southern highlands southwest of Virginia and into the piedmont area of north Georgia. The very common tulip poplar also belongs to the magnolia family, but it is classified in a separate genus. Of the six species four grow locally, two have been introduced, and one is rather rare, so the only magnolia trees that we are likely to see tramping around the woods are the Fraser magnolia, the cucumber tree (M. acuminata), and the umbrella magnolia (M. tripetala). All three of these common native species have deciduous leaves and bloom in late April, through May, and into June.

Fraser magnolia trees are typically found in rich cove and acidic cove forest areas, both of which are classified as lower mountain elevation/moist to wet communities, and they are found in many areas of Transylvania County, where I live, with its mild climate and abundant rainfall and forests. A rich cove forest occurs at low to moderate elevation with deep shade in several areas, often in rugged terrain with dense glades of trees and steep rocky slopes. The soil is deep and dark, and less acidic than in other forest areas because the underlying base-rich rocks release minerals into the soil. Magnolia trees grow less commonly in acidic cove forests which have soil that is, not surprisingly, more acidic. Such forests usually are underlaid with more acidic bedrock such as granite. There is usually a dense layer of heath shrubs in an acidic cove forest, and there are many such forest areas in Western North Carolina.

Fraser magnolias are, in general, understory trees that are happy with shade and usually found growing in small openings in the forest. They are relatively fast growing trees with multiple limbs, however, and can become a canopy tree if they are close to a larger opening in the forest. Apparently, this is what happened to our magnolia tree because when we cleared the land to build our house, we gave it plenty of room to grow tall. Fraser magnolias have thin bark so they are vulnerable to fires and insect damage, but they can grow back quickly if injured, sprouting new growth readily from the base of the tree.

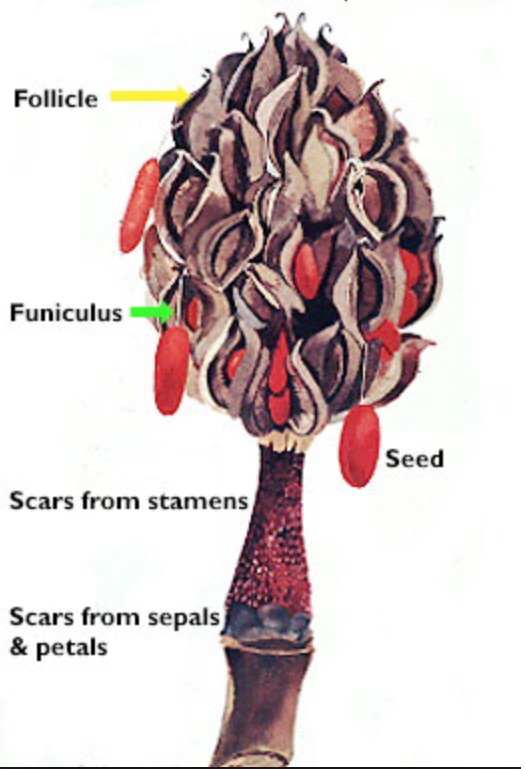

Fraser magnolias produce fruit from late July into early September. Like the flowers, magnolia cones catch the eye. They are woody with several small pod-like follicles, each containing one or two scarlet seeds. When they are ripe, the seeds are “ejected” from the follicles but instead of falling out of the pods, the seeds remain suspended in the air by almost invisible, elongating threads. Some of the threads are as long as three inches, and the seeds may remain suspended for several days before falling. Apparently, magnolia trees have adapted to attract birds that can eat and disperse seeds at significant distances from the parent tree, and birds can more easily locate bright red seeds that are dangling in the air than seeds that have fallen to the ground.

Magnolia flowers are sweet-smelling, but the ripe fruit is high in fat and low in sugar which makes it taste rancid to mammals. Birds don’t care, however, because they don’t have a strong sense of either smell or taste. Magnolia seeds are excellent food for them in the late summer and fall because they need as much fat as they can eat for their migrations and the colder weather.

Why did I label Fraser magnolias an ancient botanical relic? About 300 million years ago, the Southern Appalachians were young rugged mountains and there were no mammals, birds, reptiles or flowering plants. The dominant plants were tree-sized ferns, horsetails and club mosses, and the dominant land animals were prehistoric salamanders. It wasn’t until about 150 million years later that dinosaurs became the dominant land animals. But some early primitive flowering plants, including magnolias, had also evolved by then. It wasn’t until 65 million years ago, after the dinosaurs were extinct, that flowering plants, mammals, and birds began to rapidly evolve and diversify. One of the most important evolutionary strategies for flowering plants was to attract and use insects to transfer pollen from plant to plant. Because magnolias were among the earliest flowering plants, they adapted to pollination before bees existed and so are pollinated by beetles instead. Magnolias are indeed botanical relics, and there is much to admire about them including their staying power.

References: Frick-Ruppert, Jennifer. Mountain Nature. The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill. 2010

Spira, Timothy. Wildflowers and Plant Communities. 2011

Ellison, George. Smoky Mountain News 18 May 2011

Top photo by Linda Martinson Fraser magnolia blossom

6 comments