We will remember you ...

As 2007 draws to a close, here at Page 2 we thought we'd pay tribute to several of our favorite sports figures, large and small, who called it a career this past year.

(Sarah McLachlan soundtrack not included.)

Craig BiggioCraig Biggio's name has never been linked to performance-enhancing drugs, but I know two things he tested positive for during his Hall of Fame career: hustle and dirt. Despite playing much of his career in the Astrodome, Biggio always found a way to get dirt on his uniform. But (and no offense to David Eckstein here) Biggio was much more than a scrappy hustler: He's arguably one of the top 50 players in the game's history.

He came up as a catcher, became an All-Star, moved to second base and was a Gold Glover. He topped 10 home runs just once in his first four seasons, but finished with eight seasons of 20-plus home runs. He stole 50 bases once; he hit 56 doubles another time; he scored 146 runs in 1997 (only Astros teammate Jeff Bagwell has scored more in a season since 1950); he once played 162 games and didn't ground into a single double play; only 12 players have scored more than his 1,844 runs.

And, those 12 are all legends of the game -- names like Mays, Cobb, Aaron, Musial, Gehrig. His run scoring ability offers a little insight into how underappreciated Biggio was during his career; after all, isn't the object of the game to score runs?

For a time, it appeared Biggio's legacy (shared with Bagwell) would be one of failed Octobers. From 1997 to 2001, the Astros lost four straight playoff series and Biggio hit .083, .182, .105 and .167 in them. Finally, in 2004, Biggio hit .400 as the Astros beat the Braves for the first playoff win in franchise history. Although they lost to St. Louis in the National League Championship Series that year, in 2005 the Astros reached the World Series as Biggio hit .316 and .333 in playoff series victories. Biggio was past his prime by then, but at least he finally showed a glimmer of his greatness on a big stage.

-- David Schoenfield

Drew Bledsoe

First he was the guy picked No. 1 in the 1993 NFL draft -- and he (along with new coach Bill Parcells) was going to save the New England Patriots. Then he was the guy who led the Patriots to the Super Bowl in his fourth season, only to lose to the Packers. But then he was the guy getting drunk and doing stage dives at an Everclear concert.

Then he was the guy who signed a then-record 10-year, $103 million contract. But then he was the guy who got hit so hard by Jets linebacker Mo Lewis, he suffered a sheared blood vessel in his chest. And that made him the guy who gave up his job to Tom Brady.

The rest? Well, there were glimmers of the good ol' days. Like when he left for Buffalo in 2002 and opened the 2003 season with a 31-0 spanking of his former team. But he eventually lost his starting job there to J.P. Losman in 2005. Then he reunited with Parcells in Dallas and almost single-handedly led the Cowboys to the playoffs in 2005. But then he lost his starting job to Tony Romo.

That was it for Drew Bledsoe. Because, as we learned, he was many things, but he was never going to be anyone's backup.

-- Mike Philbrick

Frank Broyles

Broyles is retiring on Dec. 31 after more than 60 years in college sports. He quarterbacked Georgia Tech to four bowl games, coached the Arkansas Razorbacks to seven Southwest Conference titles and a national championship, then he oversaw 43 more national championships in other sports as Arkansas' athletic director. The Broyles Award is given out annually to the top assistant football coach in his name, a fitting honor given that so many of his former assistants (Jimmy Johnson, Barry Switzer, Joe Gibbs, Johnny Majors) went on to win national championships and Super Bowls.

But what college football fans outside of Arkansas will remember most about Broyles is his wonderful TV analysis. Back when college football was essentially limited to one or two broadcasts on just one network each Saturday, he and partner Keith Jackson were the voices of the sport. We're still not sure how the athletic director of a school could be hired as an objective analyst, but for fans of a certain age, college football broadcasts haven't been the same since Broyles was in the broadcasting booth and demanding at least once a game, "Keith, where was the safety-man?"

Congratulations on a great career, Frank.

-- Jim Caple

Jeromy Burnitz

Early in his career, it appeared Jeromy Burnitz would be a flop. A first-round draft pick by the Mets in 1990, he reached Triple-A in 1992 and hit .243. And then hit .227 the next season. And then .239. The Mets gave up on him and traded him to Cleveland. He spent almost the entire 1995 season in Triple-A yet again.

In 1996, he was 27 years old and had hit 16 career home runs in the majors. His baseball future looked bleak. Eleven seasons later, he finished with 315 home runs, four 100-RBI seasons and an All-Star Game appearance. Pretty good career for a guy who looked like a Triple-A lifer.

Back when Burnitz was with the Brewers, I was doing a story on the final year of County Stadium. The Brewers had neglected to keep the park up, wooden bleachers were rotting and peeling paint, money wasn't being invested in players. As Burnitz told me at the time, the Brewers were cheap. Although he appreciated the organization for giving him the opportunity to start the Mets and Indians hadn't, he wanted to play for a team that had a chance to win.

He did finally get out of Milwaukee, going to the Mets, Dodgers, Rockies, Cubs and Pirates. But he never did get to play on a winner; Burnitz played 1,694 games but never made the postseason. And although "most games played by an active player without a postseason appearance" isn't the way you want to go out, it sounds a lot better than "Triple-A lifer."

-- David Schoenfield

Lloyd Carr

"What have you done for me lately?"

That's how fans often treat coaches in the fickle world of big-time college football. It's why Carr, who's retiring after 13 seasons at the helm of Michigan's football program, will be remembered by some as the guy who lost to Appalachian State and went 1-6 in his last seven matchups against archrival Ohio State.

But it would be shortsighted to overlook Carr's 121-40 record and five Big Ten titles. He also coached star players such as Charles Woodson, Braylon Edwards and Tom Brady. And the crowing achievement of his career, as Michigan fans won't soon forget, was the 1997 national championship season, headlined by Woodson winning the Heisman Trophy and capped by a thrilling victory over Washington State in the Rose Bowl.

Even en route to retirement, Carr supposedly wields plenty of influence in Ann Arbor. We'd love to ask him if he did indeed shoot down the candidacy of LSU's Les Miles to become the new Michigan coach.

But as Carr might say, "Why would you ask a dumb question like that?"

-- Thomas Neumann

If baseball analysts had their own Mount Rushmore, Branch Rickey would be George Washington and Bill James would be Thomas Jefferson.

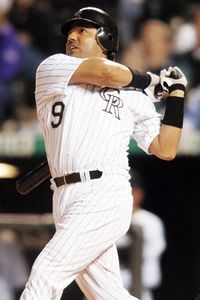

The part of Teddy Roosevelt could be played by Vinny Castilla. When the baseball world saw a fringe prospect turn into the second coming of Mike Schmidt for five seasons, everyone from GMs to casual fans could no longer ignore the Colorado Effect, not to mention the effects of the other 29 major league ballparks.

Castilla came of age in the 1980s as a skinny shortstop from Oaxaca, Mexico. When the Braves bought his contract from the Mexican League in 1990, Castilla was blocked by Jeff Blauser at the major league level and by top prospect Chipper Jones in the minors. After two years and just 21 at-bats with the Braves, Castilla's career appeared headed nowhere.

The Braves left him unprotected in the expansion draft, and the Colorado Rockies snatched him up. The next two years, playing in the thin air and high altitude of Colorado, Castilla showed flashes of potential.

Then he went nuts. Castilla smashed 191 homers the following five seasons. He hit over .300 four times, slugged over .500 four times, and totaled 100 or more RBIs four times, including a ridiculous .319-46-144 season in 1998. Mile High Stadium (and later Coors Field) transformed Castilla and Dante Bichette, two previously pedestrian players, into stars. Playing in Colorado made Larry Walker and Andres Galarraga, already solid players, into superstars.

When Castilla left Colorado after the 1999 season, his numbers nosedived. Signed by Colorado for one last hurrah at age 36, he suddenly rediscovered his stroke, blasting 35 homers (the most he'd hit in six years). But after being let go by the Rockies, his production immediately tanked again. He was out of baseball two years later.

So consider this a warm thank you, Vinny. Thanks for going from being an unknown underdog to a Colorado legend. And thanks for making all of us smarter baseball fans.

-- Jonah Keri

Roger Clemens

Did any player do less to earn his pay in 2007 than Clemens? He came out of "retirement'" to sign with the Yankees for a prorated $28 million, won only six games, hurt his hamstring, didn't get out of the third inning in his postseason start, and then was the biggest name in the Mitchell report. Which makes me wonder: given her over-the-top reaction when Clemens signed with the Yankees, how might Yankees radio broadcaster Suzyn Waldman describe the rest of his year?

The Rocket's hamstring is strained and he'll have to hobble off the mound. The trainers have dropped ropes around him and are trying to keep his ERA from floating away. Roger has lost again and it is starting to rain and lightning is crackling -- oh my goodness gracious! The Mitchell report has struck Roger and his reputation is bursting into flames! This is terrible! This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world of sports! It is a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. The moral outrage is climbing hundreds of feet into the sky! Roger's reputation is in smoke and flames now. Oh, the humanity! Those fans! I can't talk, ladies and gentlemen! Honest, Clemens' legacy is a mass of smoking wreckage. This is terrible! Listen, folks, I am going to have to stop for a minute because I have lost my voice and also wet myself once again.

-- Jim Caple

Rheal Cormier

The definition of a notable reliever is, when he takes the field, everyone knows the game is over. That was true about Rheal Cormier -- but more often than not, it wasn't for the right reasons.

So how does someone who is 5-foot-7 and 187 pounds with a career ERA over 4.00 manage to play for 16 years? Easily: you throw left-handed.

Cormier did have his occasional highlights -- like his 1.70 ERA in 2003 with Philadelphia, and the fact that he physically survived being in the same clubhouse as Carl Everett in Boston.

It was an interesting journey for Cormier, from the Cardinals to the Red Sox to the Expos to the Indians, back to the Red Sox, then to the Phillies to the Reds to oblivion (aka a minor league contract with the Braves). In the end, Cormier's career can be summed up in his own words, as he tried to explain to The Boston Globe how he blew a game against the Yankees in 2000: "I just didn't throw it where I wanted to."

So what do you do when you're 40 years old and you wake up one morning on the Braves' Triple-A affiliate in Richmond? Well, you retire. Keep it real, Rheal.

-- Mike Philbrick

Sure, the football factories recruited Marshall Faulk … as a defensive back.

Only one school, San Diego State, was interested in him as a tailback. And he began his freshman year fifth on the Aztecs' depth chart. It wasn't long before he made headlines, though, rushing for a then-NCAA Division I-A record 386 yards against Pacific and leading the nation in rushing yards as a true freshman. He led the nation in rushing again as a sophomore, finishing second to Gino Torretta for the 1992 Heisman Trophy. Faulk was a three-time All-America selection, and his 12.1 points scored per game remains an NCAA career record.

Faulk was selected No. 2 overall by the Indianapolis Colts in the 1994 NFL draft, and went on to become one of the finest dual-threat tailbacks in NFL history. He was named to seven Pro Bowls, won the 2000 league MVP award, and played in two Super Bowls with the Rams, winning one.

He finished his pro career with more yards from scrimmage than Marcus Allen, more rushing yards than Thurman Thomas, and more receiving yards than Lynn Swann. Faulk is a mortal lock to reach Canton on the first ballot. Torretta, on the other hand, will have to buy a ticket just like you and me.

-- Thomas Neumann

Julio Franco

I used to have a friend who said he knew he was getting old when he noticed most of the Playboy centerfold models were younger than he was. I had the same epiphany a few years later, when I realized I was older than most of the players on my favorite team, the New York Mets. Hmmm, I thought … maybe I wasn't going to grow up to become a ballplayer after all?

Still, I figured as long as there was one Met older than I was, I could still nurture my fantasies of making it to the bigs. John Franco, for all the frustration he caused on the mound, earned his roster spot season after season simply by virtue of being four years my senior. When he retired in 2005, the Mets obligingly brought in Andres Galarraga (three years older than me) for a spring training look-see. But when the Big Cat retired just before Opening Day this season, I thought my dream was finally over.

Ah, but then came Julio Franco -- not just older than me, but older than Yogi Berra (almost) -- a living, hitting beacon of inspiration to anyone who's ever worried about time's relentless advance. And he was still using that crazy wraparound batting stance that should have been impossible even back when he was 30! If he was still making a living as a ballplayer at age 67 (OK, actually 48), then surely there was still plenty of time for me, a relative young buck at 43.

Alas, the calendar finally may have caught up with Franco this past season, when he hit only .222. His bat speed has slowed, and his range in the field is almost nil. He's declared for free agency, but it's hard to see anyone signing him -- a tragedy for those of us who believe in baseball's ability to turn anyone into a little kid. Thanks for keeping the dream alive a bit longer, buddy.

Fortunately for me, the Mets still have El Duque.

-- Paul Lukas

Tim Henman

Above the player's entrance to Wimbledon hangs an inscription from the poet Rudyard Kipling, an old chestnut about triumph and disaster being twin impostors. It's a noble sentiment, quintessentially British, and basically a load of high-minded bollocks.

Except when it comes to sports. Except when it comes to Tim Henman. Year after year, Henman was Centre Court's almost-man, England's annual summer obsession, pushing deep into the draw with his deft touch and throwback serve-and-volley style; year after year, he invariably fell short of a longed-for title, crushing the hopes of the throngs gathered on "Henman Hill," leaving the Fleet Street tabs to run headlines like "WE'RE A NATION OF LOSERS." Only losing never really mattered. Winning never really mattered.

What mattered was Henman's effort -- the rollicking runs through the bracket, the thrilling comebacks and gut-wrenching gag jobs, the whole wide range of hope and despair and human emotion spurred by two men smacking a fuzzy yellow ball across a patch of grass.

Henman was good, but never good enough, and so what? Sports are a roller coaster. The end is the least interesting part of the ride.

-- Patrick Hruby

Let's play the $25,000 Pyramid, shall we?

"Men in thongs"

"The last third of 'I Am Legend'"

"Martina Hingis' excuse for retiring"

Answer: Things that just ain't right.

Seriously, if every professional athlete just up and retired after being linked to drugs, what would we watch on TV?

As a player, the diminutive Hingis never gave up on a point. Not during her peak in the late '90s, and not during her comeback in 2006. So it just seems odd that she would throw in the towel so quickly after twice testing positive for cocaine -- an allegation she full-heartedly denies, but didn't really bother to stick around to disprove, either.

I guess between that and the nagging injuries, she just didn't feel like fighting for her reputation. That's too bad, because 209 consecutive weeks as the top player in the world seems like an honor worth fighting for. Unless, of course, you're guilty and figure it'd be best to walk away from a PR nightmare rather than stick around and get killed (cough, cough … Floyd Landis … cough).

But in a sports world in which accused murderers, rapists, gamblers and cheaters can send out an "If I offended anyone, then I'm sorry" apology, it just seems Hingis could've at least waited until the initial buzz blew over -- pun intended -- before deciding to quit. She was no longer a Grand Slam caliber player, but she's only 27 and could still cover the court like few others.

Then again, this is also an individual who called openly gay Amelie Mauresmo "half a man," said the Williams sisters have it easier because they're black, and said Steffi Graf's "time had passed" and then went out and lost to her in a French Open final.

On second thought, maybe it's a good thing she just shut up and left.

-- LZ Granderson

Keyshawn Johnson

On May 23, 2007, "Just Give Me The Damn Ball" became "Just Give Me The Damn Microphone." After an unceremonious final season with the Carolina Panthers, Keyshawn Johnson laid his 11-year NFL career to rest.

The USC product's career achievements include: three years with Bill Parcells and the New York Jets, winning a Super Bowl with Tampa Bay in 2002, and being deactivated by Tampa because of his rocky relationship with coach Jon Gruden. Because of Johnson, the Eagles knew exactly what to do when Terrell Owens got mouthy. Nevertheless, Johnson has never been shy about his opinions. He once called Bucs teammate Ronde Barber an "Uncle Tom," and his confrontational interview with Chad Johnson was one of the most memorable of the NFL season.

"Just Give Me The Damn Microphone" transformed into "Just Give Me The Damn Answer."

-- Jemele Hill

Cobi Jones

To grow up playing soccer in the 1990s was to idolize Cobi Jones.

-- Mary Buckheit

Marion Jones

Nice smile. Ran fast. In the end, that's all we really knew about Marion Jones. The rest of it -- Jones as golden girl, as cotton-candy assassin, as paragon of strong, redefined feminine beauty and you-go-girl empowerment -- was projected claptrap. Stuff we wanted to believe. Stuff, maybe, we needed to believe.

The ancient Greeks used to do this with their gods. Lacking Apollos of our own, we do it with the next best thing: our athletes. We puff them up and fill them out and box them into tidy little narratives that serve whatever purpose we require, forgetting all the while that jocks aren't myths. They're people, mysterious and ineffable, irreducible to marketing slogans and pat cover stories. Today's giggling gold-medal winner is tomorrow's teary-eyed drug cheat, and that should never, ever come as a surprise, even though it always does.

Sometime soon, Jones will likely go to jail; the rest of us will knowingly shake our heads. What a fall from grace. Only, what if grace is also an illusion?

-- Patrick Hruby

George Herman Ruth. Eldrick Tiger Woods. Cassius Marcellus Clay. Wayne Douglas Gretzky. Charles Frederick Kiraly. There are a handful of athletes who've meant much more to their sports than anyone else. And Karch Kiraly is one of them. Dominant at every level of competition, on the sand and in the gymnasium, Kiraly is indisputably the best volleyball player of all time. If you know nothing else about the sport, you should know the living legend in the neon-pink flipped visor. Kiraly first entered beach tournaments at age 11, with his father as his playing partner. He played in his first beach open after graduating from Santa Barbara High School, and one year later, in May 1979, he partnered with Sinjin Smith to win his first tournament at age 18. Then fast-forward 26 years to 2005, when Kiraly won his last tournament -- a victory that marked his record-setting 148th title and a career of dominance that spanned four decades. Kiraly officially retired from the Association of Volleyball Professionals in 2007, playing in his last tournament at the age of 46, among a pool of players mostly half his age. The sage godfather cultivated his credentials at UCLA, helping the Bruins compile an astounding 123-5 record and three NCAA titles (1979, 1981, 1982) in four years. After college, Kiraly went on to become the only volleyball player in history to win three Olympic gold medals, the first coming in Los Angeles with the U.S. indoor team in 1984. Olympic gold in hand, Kiraly secured volleyball's triple crown by adding the 1985 World Cup and the 1986 World Championship to his mantle. And in 1988 at the Seoul Olympic Games, Kiraly took home his second gold. Four years later, Kiraly retired to the sand full-time, and immediately proved to be the paramount player on any surface by winning 16 opens in 1992, 18 in 1993, 17 in 1994, 12 in 1995 and 11 in 1996. He was the MVP of the AVP six times, and in his 27 years as an active tour player, he nabbed at least one tournament title in 24 of those seasons. Appropriately, in beach volleyball's Olympic debut at the 1996 Atlanta Games, Kiraly (with playing partner Kent Steffes) won the sport's inaugural Olympic gold, his crowning achievement. Kiraly is the best ever. No asterisk. No argument. No caveat. No controversy. Just an athlete whose talent is all there is to talk about. Here's to a relaxing retirement, Karchy. Plain and simple. Just like your legacy.

-- Mary Buckheit

Floyd Landis

Floyd Landis' road-racing career may not have ended in 2007, but his tires are flat, his frame is cracked, the peloton has dropped him and Alpe d'Huez is straight ahead.

His battle to hold on to the yellow jersey he won in the 2006 Tour de France suffered a devastating blow when an arbitration panel ruled 2-1 against him in September. The panel did so even though it acknowledged that the testing laboratory's standards were so sloppy that it should be placed on double-secret probation. As the dissenting arbitrator, Christopher Campbell, put it, "Mr. Landis sustained his burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The documents supplied by [the lab] are so filled with errors that they do not support an Adverse Analytical Finding. Mr. Landis should be found innocent."

You don't win a Tour de France by giving up easily, and Landis is trying one last appeal to the Court of Arbitration. If he loses, he's banned from racing until January 2009, which means he'll be almost 34 before he could next compete in the Tour de France. Precious few riders are able to challenge for the Tour championship at that age.

Still, given the determination Landis has already shown, don't be entirely shocked if he's back climbing through the French Alps in two years, giving it his best shot.

-- Jim Caple

Eric Lindros

He was supposed to become a hockey legend. At 6-foot-4, 230 pounds, Lindros was the super-hyped No. 1 overall pick in the 1991 NHL entry draft by Quebec. He refused to play for the Nordiques, earning a trade to Philadelphia and a reputation as a prima donna.

Lindros won the Hart Trophy as MVP in 1995, and he led the Flyers to the Stanley Cup finals in '97. He never could live up to the unrealistic hype, however, and was considered fragile after incurring numerous injuries. Ultimately, he became somewhat of a sympathetic figure by refusing to quit following concussion after concussion -- eight in all.

Despite the injuries, he recorded 865 points in 760 career games and is a legitimate Hall of Fame candidate. Should he be inducted, we suggest he wear a helmet to the ceremony … because you never know where Scott Stevens might be.

-- Thomas Neumann

Gary Payton

"Who could ever root for that guy?"

Surely, you've been watching an NBA game and, at some point, uttered that sentence to yourself. You know the guy I'm talking about. He's talking smack for 48 minutes strong, telling everyone how good he is and constantly pointing out where you … um, fall short. He's a bad practice player, infamous for doing little in workouts to help his teammates improve. His "training table" notoriously includes a couple of hot dogs at halftime. He's hell on coaches, talks back in the huddle and publicly embarrasses the man at the head of the bench. And he's surly and redefines the term "difficult" -- once rumored to have thrown a barbell at a teammate during an off-day workout.

Gary Payton did all those things during his 12 seasons in Seattle. I hate every one of those things. And yet I will say right here that Gary Payton is my favorite athlete of all time.

Yes, Seinfeld was right: We're "rooting for laundry" in sports, and no one has ever worn the Seattle SuperSonics' laundry better than the Glove. But it's more than just the fact GP became the face of the Sonics, leading them to the playoffs in 10 of his 12 seasons, including a trip to the 1996 NBA Finals.

It's the way he played. No one ever hustled more. The man was constantly in motion on a basketball court -- all over the floor for 40 minutes a night. If you hate players who don't hustle on defense, you loved Payton. And he did it every night, amassing two streaks of at least 350 consecutive games played (the first stopped not by an injury, but a one-game NBA suspension). I remember one night in Minnesota when GP came down awkwardly on the scorer's table as he was trying to save a loose ball. The next morning, the talk in Seattle was that the point guard would miss a couple of weeks. He played that night and led Seattle to victory.

That was Payton. Night in, night out. All in, all out. Nine times an All-Star. Nine times on the All-Defensive Team. A steals champion (1995-96). An assists champion (1999-2000).

And at last an NBA champion -- although, sadly, his title came with Miami in 2006, and not with Seattle. I'll miss that hustle, that sneer and the in-your-shorts defense. I'll even miss all the things that I used to "hate."

-- Kevin Jackson

Mike Ricci

Mike Ricci was one of those once-in-a-generation players.

There are athletes like David Beckham, Tom Brady and Michael Jordan who rise to fame behind their talent and good looks. And then there are those like Otis Nixon, Sam Cassell and Gheorghe Muresan, who become known for being horribly, horribly, horribly ugly.

Ricci fell into the latter camp. Although that association besmirches the likes of Nixon, Cassell and Muresan. Ricci was uglier. Much uglier.

In fact, if you created a person out of the worst genes of those three, raised it in a kennel, beat it about the face every night with a hockey stick and never washed its hair, you'd get Mike Ricci on the day of his high school senior picture.

Now, Ricci could play hockey. He scored 243 goals and tallied 605 points during 16 seasons with the Flyers, Nordiques/Avalanche, Sharks and Coyotes. And he put some important goals in the net along the way. Although I can't remember any of them. They likely banked in off his face, giving him a fresh welt, or cut, or -- more likely -- the pucks simply saw his face while flying through the air and turned into the net to hide in terror.

So feel free to remember Ricci as a gritty, productive NHL veteran. But I choose to remember him this way. And this way. And this way.

-- DJ Gallo

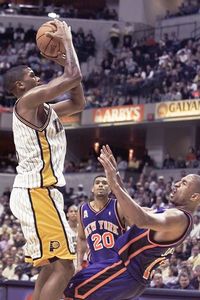

AP Photo/Michael Conroy

Reggie Miller got more attention, but Rose was an All-Star caliber player for the Pacers.

It should've been you, Jalen.

After Chris Webber grabbed that rebound, it should've been you -- the team's point guard -- taking the ball from him, dribbling up court and setting up a play in the final moments of that championship game against North Carolina. Webber panicked and called a timeout, but he should never have been placed in that position in the first place. He gets the blame, but it should've been you.

It should've been you, Jalen.

When the roster was named for the 2000 NBA All-Star team, it should've been you -- not Reggie Miller -- representing the Pacers. You were the team's leading scorer, and a perpetual matchup headache for opposing coaches. True, you were named Most Improved Player that season. But that award sort of suggests you stunk the year before. You deserved better that season. When the lights were flashing and the names were being introduced that night in Oakland … it should've been you.

I hope it was you, Jalen.

Instead of being booted out of the NBA -- because, let's face it, you got no run in Phoenix -- I hope you just decided to walk away. The thought of you no longer being good enough for any team in the league is not a pleasant one. You helped change the college game as a skinny freshman from Detroit, you were a fun player to watch as a pro, and through your philanthropy you proved to be one of the best the NBA had to offer.

Whenever we think of the rose that grew from the concrete … we'll think of you, Jalen.

-- LZ Granderson

Terry Ryan and Bill Stoneman

Billy Beane is a rock star, able to command the GDP of a small island nation for every speaking appearance. Andrew Friedman was a Wall Street up-and-comer, wooed to the big leagues and now running the Rays in his early 30s. Jon Daniels is equally precocious, just past his 30th birthday and preparing for his third season as GM of the Rangers. With that kind of competition, it's not hard to see why Terry Ryan and Bill Stoneman, after spending their entire lives in the game, decided to hang 'em up this year.

As general managers, Ryan and Stoneman were cut from the same cloth -- they just happened to have different employers. Ryan took over the Twins job in 1994, replacing Andy MacPhail after the Twins won two World Series in five years. The Twins struggled for the first few years of Ryan's tenure. But as the gap between MLB's haves and have-nots widened and billionaire Carl Pohlad established his reputation as the cheapest owner in sports, Ryan got to work. Eschewing big-ticket free agents, Ryan and his crack scouting and player development staff rebuilt the team from the ground up, churning out great young players and grabbing promising prospects on the cheap. From 2002 to 2006, the Twins won four of five division titles, proving that there's more than one way to run a franchise.

Stoneman took the helm for the Angels after the team's dismal 70-93 season in 1999. With an assist from the previous regime, he set out to build a formidable farm system of his own. Led by homegrown stars, the Angels won the World Series in 2002, just three years after Stoneman's hiring. And the years that followed brought more success, including three division titles from 2004 to 2007.

For all their success, though, Ryan and Stoneman also drew criticism for the same reason: their conservative nature. Armed with Arte Moreno's checkbook and a loaded farm system, Stoneman had many chances to make a blockbuster deal, but chose to stand pat each time. His lack of action frustrated many Angels fans, especially when the team failed to get back to the World Series in three tries. Ryan didn't have the same resources, but he still drew many of the same rebukes, failing to make the deals that could've surrounded his young stars with the complementary talent needed to make a World Series run.

Still, both men did their jobs, and left their jobs, on their own terms. We just may have witnessed the end of an era: old-school talent evaluators in a young man's game.

-- Jonah Keri

Mack Strong

I never saw Mack Strong play football.

Well, I shouldn't say that. Undoubtedly I saw him play. I just never actually noticed him.

That's because Strong played one of the most thankless jobs in professional sports: fullback. But he played it really well, even if he didn't get much recognition for it -- despite having perhaps the most fitting name in NFL history.

Strong was undrafted out of the University of Georgia in 1993. But the Seattle Seahawks signed him after the draft, and he went on to enjoy an excellent 15-year career, paving the way for three 1,000-yard rushers: Chris Warren, Ricky Watters and Shaun Alexander. In 2005, he finally was named to his first Pro Bowl. And in 2006 he went back to Hawaii for a second time.

But in Week 5 this season against the Steelers, Mack Strong's life changed. He suffered what was originally labeled a pinched nerve in his neck. A day later, it was revealed that the injury was actually a herniated disc that pinched his spinal cord. If he played football again, he'd be risking serious spinal cord damage.

Suddenly, Strong's football career was over. He had played his last NFL game.

Just goes to show, the very strongest of names can't make you invincible. And life, or your livelihood, can be taken away from you in a heartbeat -- something we all should keep in mind.

Congrats on a great career, Mack.

-- Kieran Darcy

Jerry West

As a kid living in Long Beach, Calif., I admired Jerry West for the easy, automatic way he stopped and popped from anywhere on the floor. On weekday afternoons I'd stay late on the courts at Tincher Elementary trying to emulate him, searching for some semblance of that mysterious grace of his. He was everything I wanted to be. Fluid, and fearless.

As a man living the second half of his life in Long Beach, my grandfather admired West for the sturdy, stoic way he bore his losses. Before the Lakers won the 1972 NBA championship (West's only ring as a player) West played in and lost seven NBA Finals series, and he lost another in 1973. "He knows what it is to hurt," Papa told me once. "And he never stops coming."

Remember, before he was the logo, before he was the gold standard for GMs everywhere, West was a baller. A gifted athlete with a grinder's heart.

-- Eric Neel

Corliss Williamson

You don't see it in his career NBA line (11.1 points per game, 3.9 rebounds). And you didn't see it on the NBA floor, where his 6-foot-7 frame looked slight. In the pros he was just a guy who found a niche and mined it; played smart, played hard, but never really commanded your attention.

But let's not forget that Williamson was once a beast, a mythic figure opponents dreamt terrible dreams of in the night. As the leader of a very good Arkansas team that won one NCAA title and played for a second, Williamson owned the blocks, and crushed the spirit of the poor mugs who suited up against him. There was nothing pretty about it. He didn't have much of a shot, or any kind of handle. There were no signature moves to speak of. All he had were sledgehammer shoulders, an anvil for a backside, and a no-quarter nasty streak a mile long.

We measure everything by how a guy does at the pro level. We measure everything by the last best effort. But if Williamson looks average by those measures, that shouldn't obscure his supernatural past.

-- Eric Neel

AP Photo/Francis Specker

Tim Worrell will certainly be remembered by Jeff Pearlman at least.

On a warm March day in 2003, I approached Tim Worrell in the San Francisco Giants' spring training complex, anxious to inquire about the life and times of a journeyman relief pitcher.

"Tim," I said, "my name's Jeff Pearlman, and I'm doing a piece that'd probably interest you. Do you think I could talk to you for a few minutes?"

In the midst of dislodging muck from beneath one of his fingertips, Worrell looked up and nodded. "I'm a little busy right now," he said. "Gimme a second."

With that, I stepped back, leaned against a nearby wall and -- as baseball writers do for 97.8 percent of their professional existence -- waited.

I waited as Tim Worrell walked to the bathroom.

I waited as Tim Worrell returned from the bathroom.

I waited as Tim Worrell ate a piece of fruit.

I waited as Tim Worrell threw out the core.

I waited as Tim Worrell ran his fingers through his hair.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the first page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the second page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the third page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the fourth page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the fifth page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the sixth page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the seventh page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the eighth page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the ninth page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the 10th page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell looked up at me.

I waited as Tim Worrell looked away.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the 11th page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as Tim Worrell spit into a cup.

I waited as Tim Worrell quizzically studied the spit in the cup.

I waited as Tim Worrell adjusted himself.

I waited as Tim Worrell loudly passed gas.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the 12th page of an outdoorsman magazine.

I waited as USA Today's Chuck Johnson approached me to ask, "Who you waiting for?"

I waited as USA Today's Chuck Johnson nodded sympathetically as I pointed toward Tim Worrell.

I waited as Tim Worrell read the 13th page of an outdoorsman magazine.I waited as Tim Worrell grabbed his cap.

I waited as Tim Worrell grabbed his glove.

I waited as Tim Worrell stood up.

I waited as Tim Worrell looked at me and shrugged his shoulders.

I waited as Tim Worrell exited the room.

For all I know, Tim Worrell might be baseball's Gandhi. Maybe he was in a bad mood. Maybe he's allergic to notepads. Whatever the case, as Worrell bids us adieu following a nine-team, 14-year major league career, I think not of his 38 saves in 2003, or his career-low 2.25 ERA with the World Series-bound '02 Giants, or even his record-setting run at Biola University.

No, I think of the day he thought it was funny to make a fellow human being waste 45 minutes of his life.

-- Jeff Pearlman

Comments

You must be signed in to post a comment