Interviews

Cinema Made in Italy. An Interview With Ira Deutchman

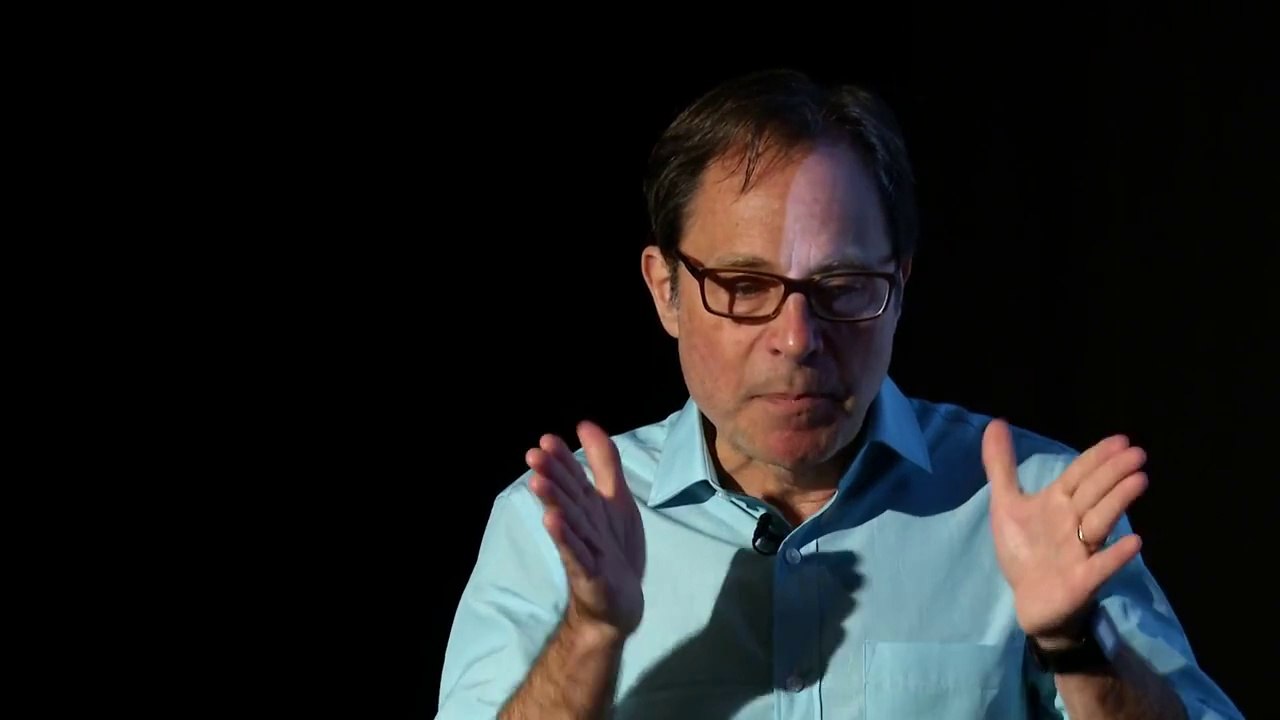

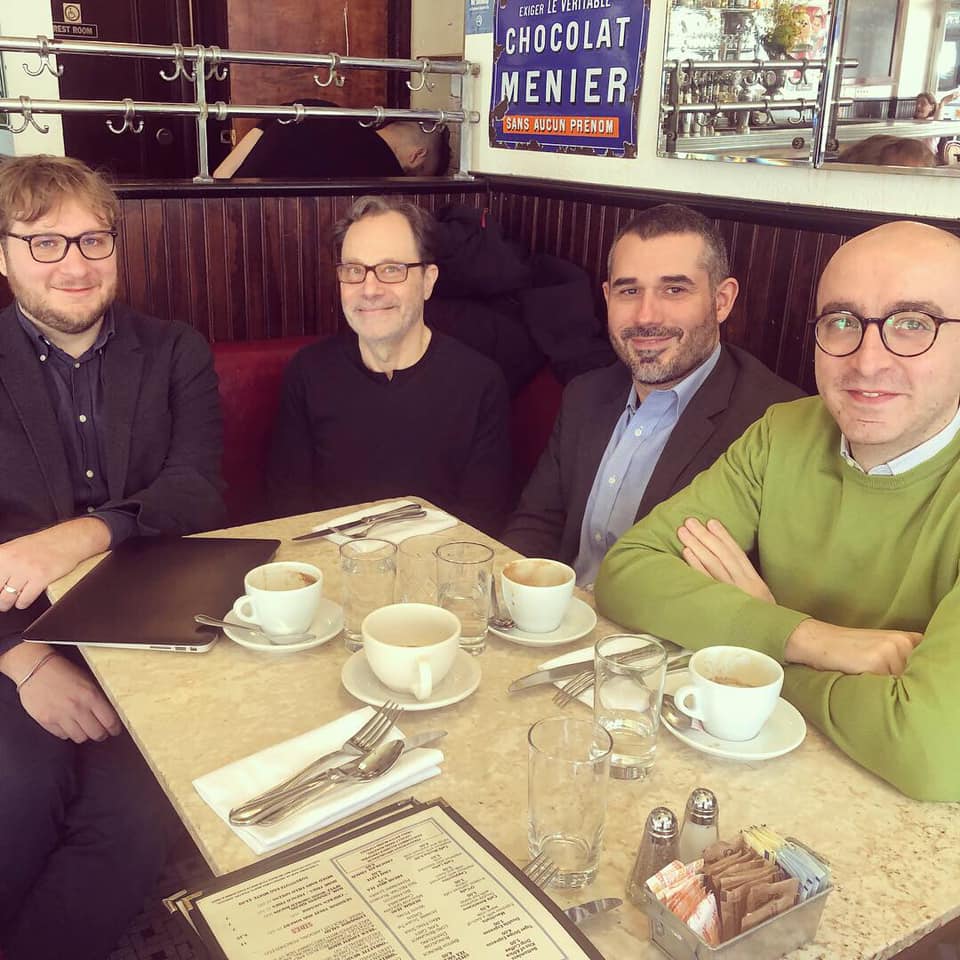

Ira Deutchman is an American producer, distributor, and marketer of independent films. In 2000, he moved into film exhibition as Co-Founder and Managing Partner of Emerging Pictures, a digital exhibition company, which was sold in 2015 to 20 Year Media. He also served as Chair of the Film Program at Columbia University School of the Arts, where he has been a Professor of Professional Practice for more than 25 years. Deutchman is also a member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He was one of the original creative advisors to the Sundance Institute and formerly served on the Board of Advisors for the Sundance Film Festival. Recently, he organized the initiative “Cinema made in Italy” (www.cinemamadeinitaly.com), a program funded and sponsored by Istituto Luce Cinecittà and the Italian Trade Commission which promotes and distributes contemporary Italian films to theaters in the United States. I had the great pleasure to meet Ira in New York City, together with my colleagues Marco Cucco and Massimo Scaglioni, on the morning of March 18, 2019, at French Roast on 85th and Broadway. He was so kind to answer a few questions on his active role in the promotion of Italian cinema in the U.S.

Can you tell us something more about your work, and the “Cinema made in Italy” series that you run?

I think it’s worth talking about the history of the “Cinema made in Italy” initiative. The way that this started was about six or seven years ago: I was approached by Roberto Cicutto, who was running the Istituto Luce at that time, and I was running a company called Emerging Pictures, which was an early adaptor of digital projection equipment. What we were doing was putting digital projection equipment into independent art film theatres and sending the films to the theatres via broadband. It was a very inexpensive way of getting sort of a broader distribution for films, and Roberto was intrigued by that. We set up this festival, a sort of a travelling festival of Italian films for theatres around the country, and that’s how we began the relationship. Emerging Pictures disappeared, mainly because when the studios started adapting digital technology they created a new standard and, as a result, independent theatres had to update their equipment to get any Hollywood movies. Our system didn’t work for them anymore. We ended up shifting the company to the Vancouver-based 20-year Media, but the relationship with Cinecittà continued.

It started out where what we were supposed to be doing was ‘acquiring’, even if that’s not the right word. Basically, Roberto gave us a fund to support Italian films that were released in the United States, and the very first film we supported was The Great Beauty. This places it in terms of how many years ago it was. What the fund has been doing has changed over time, it’s become something very specific, although the numbers change every year in terms of how much money they give us. My job is to look at the Italian films that could be possibly released in the United States, and to manage the fund so that they get distribution in the US. I work with the distributor, but I am not allowed to give the money to the distributor, I have to spend it myself. I negotiate with the distributor to make sure that they’re supporting the films with their own dollars, because the dollars that I am contributing with are supposed to be incremental, not substitutional. I have to make sure that they are spending some resources on the film, that they are really pushing it out, in sort of an aggressive way, and if they do, or if they are committed to doing that, then I use my budget to buy additional advertising, additional support, to make sure that the film gets out as broadly as possible. Then almost every year, there are a couple of films that we identify as potentially deserving a distribution in the United States, but that don’t get an international distributor. If that happens, then I distribute the movie, but all the funds come from Italy. I am not really a distributor, it’s almost like an ad-hoc distributor, where I hire the necessary people in order to do the work and we support the balance. The films we distribute ourselves require more funds than the ones distributed by somebody else.

The third thing that I do, which develops organically – it’s not necessarily through Cinecittà anymore, but it started out with them – is that I actually manage the Italian Oscar campaign every year. I did not do The Great Beauty, because it was before I started, but I’ve done every Oscar campaign since then. And, of course, the most successful one was Fuocoammare: we ended up spending a lot of money on that campaign, but it paid off, because we ended up getting a nomination for ‘Best Documentary’. This year I worked on the campaign for Dogman, and before that I distributed Indivisible, but I distributed it myself, there was no American distributor involved and then, just in the last couple of months, we supported Sicilian Ghost Story, Daughter of Mine and another release of Dogman is coming in the next months, I am working on that right now.

How do you select the films?

They leave it up to me and there’s two different aspects of it. One has to do with how much support the distributor is going to give to the film, and it’s funny because if the distributor is too big, then I probably wouldn’t support it, they don’t need me to do it; and if it’s too small and it’s clear that the distributor is only releasing it to video and they really don’t care about theatrical, then I’m likely to say no to that also. So, it’s the ones that are in the middle. Strand released both Sicilian Ghost Story and Daughter of Mine and we worked with them on another film a couple of years ago. They’re definitely on the low end of how much money gets spent on the distribution, so when I did Sicilian Ghost Story with them I decided, because I thought the movie had potential and I thought they were underestimating it, to give a lot of support. It turned out that it did better than anybody expected, but still it wasn’t a huge business. So, when Daughter of Mine came around I ended up only giving them very little support, because it was clear that they are not aggressive enough, in my opinion, about getting the film out there. Magnolia, which is releasing Dogman, is actually being very aggressive and so I’m probably going to give them a fair amount of support.

For the movies that don’t get distribution: it’s less about that, it’s more about me feeling that there is something here that I think could work. So far, the film that I released myself that worked the best was Valeria Golino’s film Honey, which we actually played in 35 cities and it did pretty good business. I thought that Indivisible might be something that could work like that, but I don’t know whether the timing was bad, we ended up releasing it pretty late, it was already more than a year-old title.

Which kind of ingredients do you think work in the United States?

I think what’s been working against Italian films in the last 5-6 years, ever since The Great Beauty, is that high-profile directors (that is to say, directors who has the most potential) are all making incredibly depressing movies. They’re all dealing with issues of immigration, the underclass and things that I think the Americans… we have our own problems, we don’t need to see the Italian version of our problems, you know what I mean? If you look at The Great Beauty, it was a film that took place in a more aspirational mode, it was not wallowing in poverty, it was different. There is only one Italian film that I saw recently that I thought could fit in this category: Veiled Naples. So, I contacted the sales agent, because I thought it could have potential, changing the title, but it turned out that they sold it to a distributor who wasn’t interested in a theatrical release at all. That’s why I ended up not supporting it. I thought it could have potential because it took place in the underclass, but wasn’t another mafia movie. That’s another thing: enough with the mafia.

Are there any specific aspects or stereotypes, like Italian tastes, in the success of a movie, or do you think that Italian specificity is not important at all?

I don’t think that’s the issue. I think it’s more about the experience through the movie. Worldwide people are pickier now about what they’re going to go to a movie theatre to see. If a film is going to be incredibly depressing, they’re not going to see it. Fuocoammare is an example of a movie that got many great reviews, it was nominated for an Oscar and we put a lot of resources into that movie, but the business was not that satisfying. You know, it’s a brilliant movie as it is but it has a very depressing set out.

Which are the specificities about distributing an Italian film, comparing to a European film? For example, in terms of the relationship with the distributors or stakeholders.

I think all distributors are dubious right now about the potential for any foreign language film in the US. The French are having very similar problems, their output of course is bigger because they have more films, but I would say that only a few more French films are distributed in the United States than Italian ones. Another thing is that France has a program where they focus on young directors and they almost give the films away; exhibitors are going to play them for one night. I think more French films get exposure in the US, but the Italians are basically number two, there’s no other country. If you look at the landscape, the films that get nominated or selected for the Oscars every year are probably a very good landscape of the best films worldwide. I feel like those films fit into a genre that Americans can’t get into and I feel like Italian cinema is in a rut: too many depressing movies similar to even American movies that don’t make money.

European cinema in the US used to follow arthouse circuit fests, so it was traditionally distributed in big cities. Do you think this is still the same for arthouse European cinema, or has something changed?

Most of the OTT services are not necessarily interested in small foreign language films, the only reason why some of them are getting bought is because they’re trying to buy worldwide rights, so they can have them in Europe. The fact they have it in the US is almost by accident. Do you know which rights Netflix bought for Alice Rohrwacher’s Happy as Lazzaro? They own it in the US and in some territories, that’s why I didn’t support it at all: they had no theatrical plan. They opened it in New York just to have reviews. They are under fire from many European governments and they want to act like they’re doing a favour for European filmmakers by buying their movies. It’s political, it’s not what United Artists used to do back in the days when they were the biggest worldwide distributor. They put money in a lot of Italian and French movies just because politically they were trying to negotiate with the United States government. They were trying to set up local distribution offices. Also, it’s important for the OTTs to have films worldwide because they don’t want to worry about borders, so I don’t think they’re inherently interested in foreign language films. I think they’re doing this for strategic reasons. But the other side of that, which is kind of interesting, is that they’re familiar with HBO show My Brilliant Friend and I think this is an example of what works for American audiences, because it’s not uplifting but it’s not pushing your face into poverty.

Do you think that the distribution of this kind of series on American TV, like My Brilliant Friend or The Young Pope, affects the distribution of other Italian products?

Well, The Young Pope was not perceived as specifically Italian, it was in English.

Do you think the Italian government or Italian public institutions should do anything more to supporting the export of Italian films?

I think they’re already doing more than many other countries, except perhaps France. What I’m trying to do, because the resources are there (they could be bigger, but they exist), is to experiment, to try to better understand what can work and what can’t. And I’m also experimenting by supporting them in different ways. What I’m talking about doing with Dogman is spending all my money on electronic media, I’m not doing any newspaper advertising. I just want to try new things, to see if we can find little pockets of audience that we wouldn’t have reached otherwise. I’m convinced that we can find a younger audience for these things, younger audiences are more open to subtitles. I was talking with my dad last night, I can’t remember which film we were talking about, but the minute he heard it was subtitled he just said “no, I can’t watch it with subtitles”. Ok, whatever.

What about the role of European Film Festivals?

They’re an important boost. First of all, the distributors count on Film Festivals for information that determines whether they want to buy a movie or not, talking to exhibitors who may or may not want to play the movie, talking to critics, trying to find out what the reviews look like. Neither of these are set in stone, but at least it gives you a clue about whether the film has a chance in the market or not. Festivals are very important from that perspective. What distributors count on is the process of narrowing, because festival directors get rid of bad movies and so the only ones they show, theoretically, are the best. That’s important, because many Italian movies, as happens in many countries in the world, are specific to the domestic market and they simply will not travel. Stupid comedies would never work in the US, neither Italian nor French.

Do you personally go to some festivals?

Every year I go to Berlin, to Cannes, to Toronto and Sundance. But, also, Roberto has people sending me new films and I have a very good relationship with Rai, and since they’re involved in almost every movie made in Italy: they’re constantly sending me stuff.

We are in a sort of a paradox because the Venice Film Festival has no film market, so it may be difficult to open to distributors.

Well, the best films shown in Venice are shown in Toronto two weeks later…

Among the top performing foreign-produced films in the US from 2000 to 2007, in terms of admissions, the only Italian films that appear are all from the same directors: Guadagnino, Sorrentino, Garrone. It’s almost always artistic auteur cinema, but this differs from the other films in the chart – even from other European nations. So do you think the Italian cinema environment is different, even from the broader European one?

If you get rid of the English language films, the same chart is going to look very different. These are Hollywood movies, except for the Italian foreign directors. 20th Century Fox, Sony Pictures: these are all major studio movies – I wouldn’t even consider them as the same category. The closest thing that Italy did I think is Call me by your name, which is hardly an Italian film. It’s directed by an Italian director, but it’s partially American money, written by an American writer, with an American cast. The question that one has to ask is: what does this do, what do any of these movies made by major studios do for indigenous French or Italian cinema? Nothing. It’s like when all the German directors came over to United States during World War II: does anybody think these are German movies?

Are you involved in the decisions about which films represent Italy at the Academy Awards?

No, I wish I was, but I’m not. I wish I could have an influence on that. I’ve talked to Roberto and it’s a very political decision, as for every country. There’s a group of Italian producers voting, but as much as everybody wants to be fair, they also have people they like and people they don’t like. They have strategic reasons to support somebody, so we end up with films that have been chosen that frankly… The minute they tell me which films have been selected I can pretty much tell you if there’s a chance or not.

When you plan strategies for releasing the film do you negotiate with directors?

Not really, it’s the sales agent more than anybody else and even they take a very minor role. I give them a vague idea of what I’m going to do with it. It’s hard to say, but at this point I think most of them are just grateful to get released in the United States, and their needs are very small. There’s one big question mark around these movies and it is whether to bring the talent to the US, because it’s a very expensive proposition, but without talent you don’t get any press. The risk is that sometimes you spend the money to bring them over and you still don’t get any press, this is embarrassing and it’s a waste of resources. The one time when a lot of Italian directors and actors are in New York is during “Open Roads” and that’s an important event for me too, because I see a lot of films there. That’s where I found Indivisible, during the opening night of “Open Roads”. I saw the film there, I talked to the sales agent at the party afterwards and I ended up distributing the movie. The problem is that by the time the movies are released, six or ten months have passed and the talent was already here, so it’s hard to get any press when the movie is released, and you don’t know whether to bring the talent again or not. It’s a dilemma.

Can you tell us more specifically which kind marketing choices you make to support a movie? Is it a general rule or does it depend on the specific movie?

It is definitely movie specific. Part of it is trying to figure out how to position the movie, to describe it in order to attract an audience and then it depends whether there is a distributor or not. If there is, we work together, and if there isn’t, it’s up to me. In terms of where we spend the money, again, it depends on the distributor and what they’re going to do. If it’s something that I am distributing I try to figure out what seems the best. There are certain things you have to do: you have to have it in The New York Times, it might be pretty small these days but that’s something you have to do. Reviews are very important.

Damiano Garofalo, Ira Deutchman, Massimo Scaglioni and Marco Cucco