Review: What Selma Blair’s memoir has to teach us all about self-medication

On the Shelf

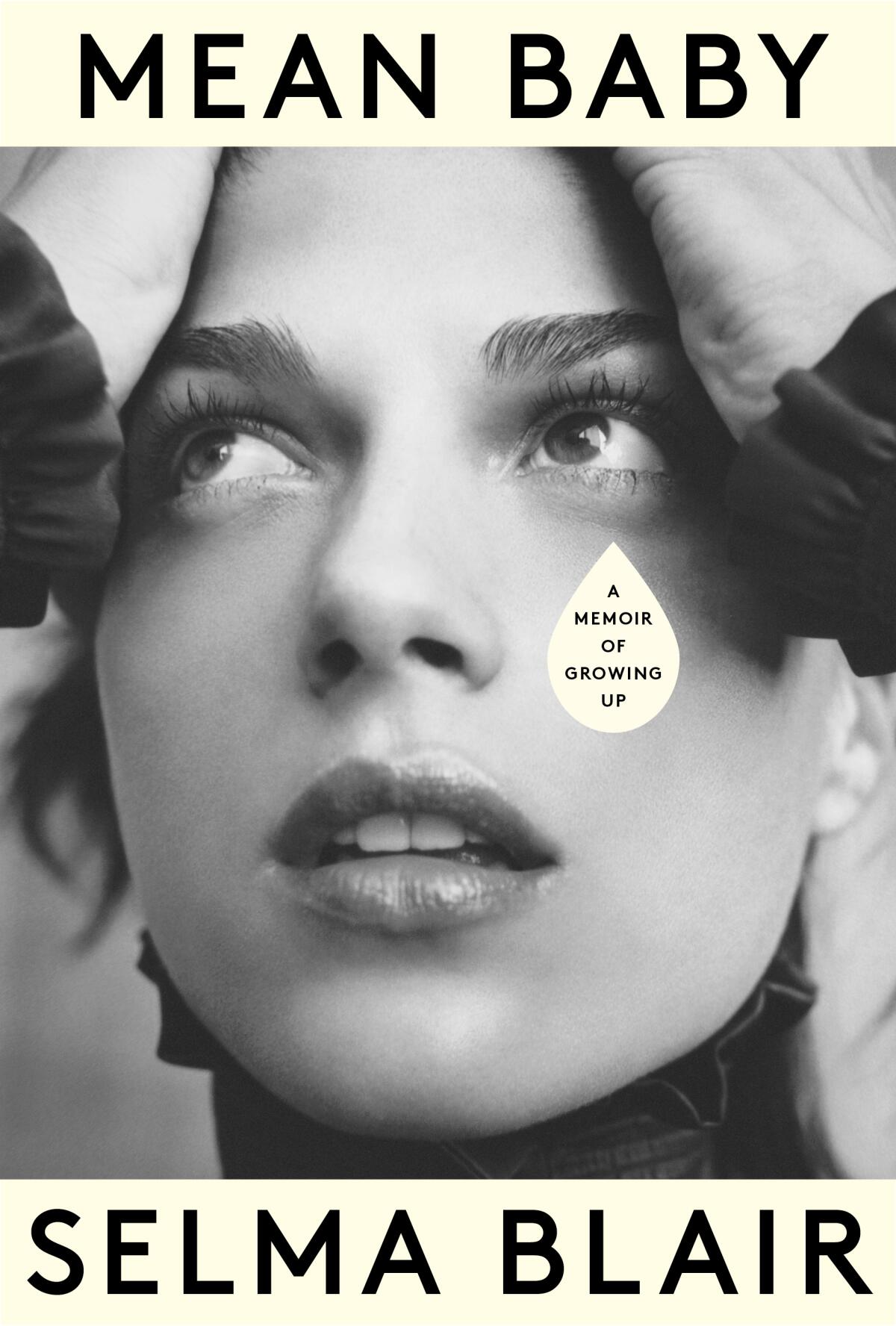

Mean Baby: A Memoir of Growing Up

By Selma Blair

Knopf: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 2018, Selma Blair revealed on social media that she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Learning the cause of many years of chronic pain and exhaustion was a revelation for the actor, who offered a visceral look at her treatment for the disease in the 2021 documentary “Introducing, Selma Blair.” She has expanded on her story in a new memoir, “Mean Baby.”

Best known for her roles in the films “Cruel Intentions” and “Legally Blonde,” Blair is a beloved cult figure in American cinema. Her offbeat approach landed her a place in the golden age of turn-of-the-millennium young Hollywood. But as her credits diminished in the 2010s, she became the target of tabloid coverage with episodes of strange behavior. As evidenced mostly recently in the case of Britney Spears, the reality behind celebrity missteps, particularly those of young women, is often much more sinister than it appears.

‘Introducing, Selma Blair,’ directed by Rachel Fleit, chronicles the ‘Cruel Intentions’ actor’s journey with multiple sclerosis.

“Mean Baby” is on one level a charming and disarming “memoir of growing up,” as its subtitle puts it. Blair is a talented writer. Her portrait of her formidable mother, Molly, is beautiful, disturbing and acutely readable, leaving you feeling that you know Molly — who called Blair a “mean baby” at birth — well enough to fear her.

But this is no frothy celebrity memoir. Pain is at the heart of “Mean Baby” — both the agony of MS and the consequences of the alcohol abuse Blair resorted to as a coping mechanism.

That pain — excruciating and inexplicable — developed as early as kindergarten. “‘My leg hurts,’ I said as my mother was racing off to work. She didn’t pay it much mind. ‘It really, really hurts.’ I dragged my leg across her bedroom to demonstrate the pain and how it gave out . . . My mother just laughed. She kept on laughing as she told the story for years. ‘What a drama queen! What an actress!’”

Blair also suffered from chronic bladder infections and fevers — ailments she kept to herself. “As a kid, you have pains, but you won’t have a vocabulary for them. Maybe it was a sign. Or maybe it was nothing at all.”

The first time Blair got drunk was during Passover. She was 7, the same year of the dragging-leg episode. “What I do know is that drinking happened to me,” she writes. “And once it did, it became my safety, a way of softening my jagged edges.” But the lines become blurred. How much of Blair’s drinking masked the pain of MS? And as an adult, how many times did Blair blame herself for being, as she puts it, just “a f— mess” rather than someone suffering from a serious illness?

When Blair was near the end of a stint in rehab, she was checked out by her father for a visit to the eye doctor. “Do you see alright?” he asks. She’s not sure. “I’d been having trouble with my vision and was experiencing some unusual pain,” she writes. The doctor doesn’t like what he sees. “You have optical neuritis. An inflammation of the nerves in the eye,” he tells her. “It’s usually a symptom of MS. Multiple sclerosis.”

When actress Selma Blair strode onto the Vanity Fair red carpet on Oscar night, her most public appearance since announcing in October that she has multiple sclerosis, what drew most attention was not her couture but her cane.

Convinced that the eye pain is a symptom of the medications prescribed in rehab, she brushes it off. At a follow-up appointment, the neuritis is gone. This would’ve been about 1998, 20 years before Blair was finally diagnosed.

In June 2016, Blair took a trip to Cancun with her ex-husband and young son. “When we got to the airport to fly home, I was exhausted, dehydrated, hungover. I thought, if I can just get some rest, I’ll be able to function as a mother again.” A fellow passenger offered Blair some Ambien to wash down with her drink. The next thing she knew, she was in a hospital with an IV in her arm.

“A blurry photo of me, taken by another passenger, appeared in all the papers,” she recalls. “Now I know I had MS symptoms that I was trying to medicate with booze, but at the time I thought I was losing my mind.”

Blair makes no excuses about her drinking in “Mean Baby.” From that day on, she writes, she’s been sober. “Knowing that my son, the person I created, that I am now responsible for, was present at a time when I lost all sense of myself — the clarity of that shook me to my core.”

In the next few paragraphs, she goes on to apologize to everyone who was on that plane. It’s obvious that she has done the hard work of recovery. Many people use alcohol and other drugs to numb themselves from emotional pain or physical abuse. Blair used it to block symptoms of a physical ailment — and that’s hardly a trivial distinction. According to recent studies, women, particularly those of color, are more likely to have their symptoms dismissed by doctors as psychosomatic. Maybe it’s all in your head. Maybe you’re just a “mean baby.”

There are plenty of celebrity memoirs that tell stories about recovery. While Blair’s is well-written and self-accountable, it stands out because it asks the right questions. Many understand that substance abuse is self-medication. As to what it is we’re medicating against — well, that’s the real story.

Taylor Harris discusses ‘This Boy We Made,’ her memoir on seeking answers about her son, the anxieties of Black parenting and her evolving faith

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.