Story and photos Jim Scaysbrook

The longest running motorcycle ever to come out of Japan made its public bow in 1974, and over 40 years later is still going strong, at least in name.

Ever since the Kawasaki Z1 hit the streets, the cognoscenti were saying that Honda wouldn’t take this lying down. Honda would hit back, they said, with something, bigger, better, faster – something that would knock the Z1 for six, and up the ante for whatever Suzuki and Yamaha may have been cooking up.

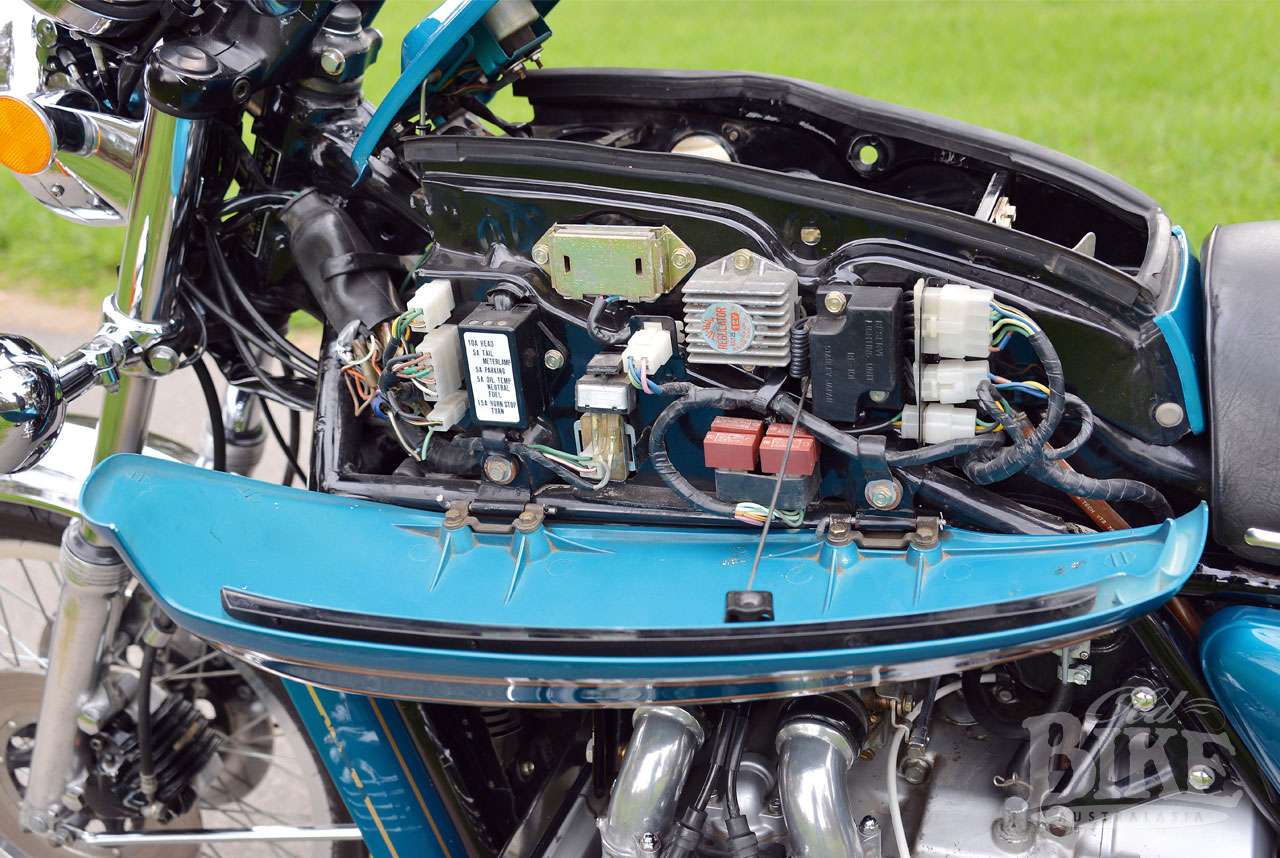

Well, the pundits were partially right. Honda was indeed up to something big, but it was in no way a challenger to the Z1, at least not in the sporting sense. The whispers intensified until – whammo – at the 1974 Cologne Motorcycle Show, there it was, in all its big, fat glory. I was there at Cologne, that cold October, and it took some pushing and shoving to even get close to the glittering red and gold machine as it rotated on its plinth before thousands of gob-smacked onlookers. There was a lot to take in, not least the cunning dummy fuel tank which, when displayed in its open state, revealed that it wasn’t a tank at all but a series of shrouds that covered all the electrical gadgetry that normally lived in the midriff of most motorcycles. The large capacity air filter also lurked under the covers, as did the radiator overflow tank, with the 19 litre fuel tank itself below in the midriff area. As if anticipating that it would rarely, if ever, be called into action, a kick-start lever lived under the right side ‘tank’ flap, and could be extracted if required and attached to a shaft behind the gearbox.

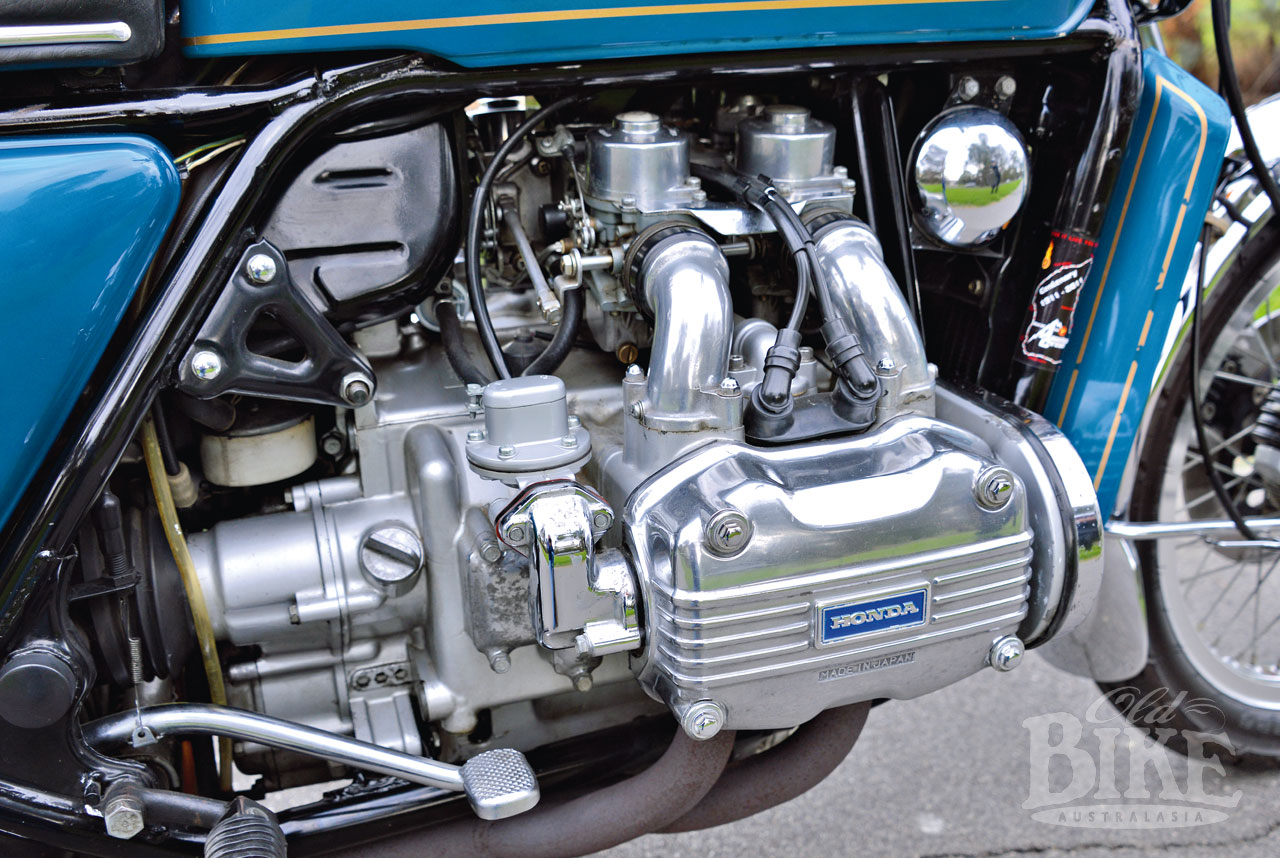

Honda had once again managed to fool everyone, for what the GL1000 Gold Wing did was not attack the big Zed’s sporting territory, as march headlong into BMW’s (and Harley-Davidson’s) touring/cruising domain. The ‘Wing looked long, but in fact it was shorter in the wheelbase than the acclaimed BMW R90S. Dominating the eyeful was the highly polished flat four engine, the concept of which had its origins back in 1972 when a design team was set up to formulate the specifications of the Gold Wing. That team was headed by Soichiro Irimajiri, then just 32 years old but with an incredible CV that included the design of the Honda Formula One RA273 engine, plus the five and six cylinder Honda motorcycle Grand Prix racers. He also had a hand in the incredible 50cc DOHC eight-valve racer and went on to design the six cylinder CBX 1000 before becoming President of Honda of America.

Irimajiri’s GL1000 was the first Honda motorcycle to employ water cooling, and the first to use shaft final drive. The design team initially worked on both four and six-cylinder concept, the latter code named AOK which used a car-style alternator driven by a skew gear from the camshaft. Eventually, the four won out, thanks largely to its more compact nature. More car thinking was evident in the use of Hy-vo belts to drive the overhead camshafts, with the cylinders cast integrally with the crankcase halves. To compensate for the torque reaction of the engine, the alternator rotor turned in the opposite direction to the crankshaft, running at twice engine speed. A mechanical fuel pump was driven from the camshaft. Gearbox was a five-speed with the unit located beneath the crankshaft, with a wet multi-plate clutch.

Chassis-wise, the Gold Wing was reasonably conventional, although it is claimed that the twin front discs were a first for a Japanese manufacturer. Both wheels were steel spoked onto aluminium-alloy rims; 19 inch at the front and 17 inch rear. A single disc was employed on the rear wheel, rather strangely 12mm larger than the front discs, and with a twin-piston calliper while single piston jobs operated on the front. The frame itself was a wide-cradle steel tube affair, with chrome-plated steel mudguards and a generously proportioned seat. Completing the visual package were a pair of almost British-style racy mufflers on the all-black exhaust system which had a hefty U-shaped centre collection system.

Naturally the publicity generated by the release of the Gold Wing in Cologne set up quite a clamour for the production machine, but almost a year was to pass before we saw it in Australia. Just prior to this, the GL1000 was tested at the MIRA Proving Ground track in UK, and rocked everyone by recording 210 km/h (130 mph) – the fastest Honda ever tested. It was also quick off the mark, reaching 100 km/h in four seconds and clocking 12.73 seconds for a standing quarter mile. The test staff praised the silky-smooth engine, and despite the wet weight of 295 kg, the machine was said to handle exceptionally well. Perhaps this was true on the wide open spaces of the Nuneaton test venue, but the GL1000 displayed what could be described as predictable handling characteristics in normal use. At low speeds, the low centre of gravity made the bike a delight to ride in traffic; it changed direction easily and behaved itself well. Through the swervery however, the weight told and the ‘Wing would tend to wander about. It was not a good idea to test the ground clearance either, as various bits would scrape when things were pushed. Overall however, the package was well-nigh perfect for its intended use – as a high speed luxury tourer its manners were impeccable.

At the time of the ‘Wing’s local release, I was a Honda dealer in the Sydney suburb of Gladesville, and although we weren’t getting the Z1-eater we had anticipated, we knew the GL1000 was the machine to open up a whole new market to us. The first time I sat on one the reaction was typical I suppose, that here was a massive machine that would be a real handful in most urban situations. I could not have been more wrong. Within seconds of getting underway it was clear that the GL1000 was a superbly proportioned motorcycle that was surprisingly quick and under most conditions, handled very well indeed. The brakes were stupendous (particularly compared to the CB750), the engine turbine smooth with effortless, surging power, and the level of appointment a cut above anything else of the road. Why, there was even an electrically-operated fuel gauge so you no longer had to dip you finger in the tank to work out the available range, as well as indicators that squawked to let you know they were indicating. We sold every one we could get our hands on, and every new owner shared my sentiments.

Retailing at $2399.00, the GL1000 was very competitively priced, with the BMW R90S ($3,095.00) and the Z1-B ($2,199.00) either side of it. If the Harley-Davidson Electra Glide was indeed considered opposition, the Honda had a $2,740 price advantage. The only flaw in its character seemed to be the process of actually starting the bike. It often took quite a bit of churning on the electric starter motor to get the motor fired up, then it insisted on a lengthy warm up period before it would run cleanly and pull away without complaining. Curiously, Honda steadfastly refused to offer original luggage or a fairing; a situation that both the German Krauser company and Vetter in America were happy to rectify to an appreciative market.

The New South Wales Honda distributors, Bennett Honda, managed by the irrepressible George Pyne, were smarting over their lack of a machine to challenge for outright honours in the highly prestigious Castrol Six Hour Race. The CB750 had won the race in 1971 but was now very much on the outer with the advent of the Z1-B, as well as the Ducati 900SS and the R90S BMW. George was always keen to try anything different, and suggested that I should team up with fellow Honda dealer and speedway star Jim Airey on a GL1000 for the running of the 1975 race at Amaroo Park on October 19. Bennett’s had a couple of Gold Wings on hand in early September, and we took one to Amaroo Park for some supposedly secret tests, which quickly revealed a few things. One was the woefully inadequate ground clearance. The footrests, muffler and centre stand all made contact with the track easily on the predominantly right hand corner circuit. Refuelling would be a bit of a chore, with the filler inaccessible and narrow. The bike was quick in a straight line, but it took great care to negotiate the up-hill right kink without inducing a fit of the wobbles, and the change of direction at the top of the hill as the weight came off the suspension was a bit of a heart-stopper as well. Much of this misbehaviour was due to the overworked rear shock absorbers, which weren’t great to begin with and soon shed nearly all traces of damping when pushed hard around a race track. But the main drawback was the 17-inch rear tyre with its high, flexible sidewalls. Within an hour, the tyre was shredded, and even with the shaft drive, changing the rear wheel was no simple or rapid job. It added up to a problematic and possibly disastrous scheme, and George negotiated a face-saving exit from the race by explaining to the organisers that it would not be possible to have the required number of models actually registered prior to the race, as the entry form required. Whew!

Bulking up

Until 1979, when Gold Wing production began at the new US Honda factory in Marysville, Ohio, the basic specification remained unchanged, although the 1978 model was face-lifted with revised ‘tank’ panels, a lower seat, revised exhaust system and Honda pressed-alloy Comstar wheels in place of the spoked items. The heavily criticised brakes with their stainless steel rotors were also completely revised. The new US model (GL1100) sported an increase in capacity – from 999cc to 1,083cc – from a 3mm increase in bore size, plus a new CDI ignition system replacing the conventional points and coil system. As well as the standard model, the Interstate sported factory-fitted saddlebags, top case and an abbreviated fairing, while the 1982 Aspencade came with an AM/FM radio and optional US-style fittings such as floorboards, plus an on-board air compressor to allow adjustment for the suspension.

For 1984, an all-new 1,182cc engine appeared, along with a much modified and much stiffer frame. The standard, un-faired model was dropped, while Interstate and Aspencade GL1200 models had completely redesigned fairings, and a year later the computerised fuel-injected GL1200LTD was added. The striking metallic gold machine also boasted a four-speaker sound system, self-levelling suspension and cruise control.

The GL1500 of 1988 incorporated the most radical change since 1974, with the four cylinder engine replaced by a new flat-six – a throwback to the original prototype. With the gradual increase of both size and weight of the motorcycle and the use of trailers and sidecars, a ‘reverse’ gear (actually linked to the starter motor) was added. The GL1500 really was a quantum leap – as it should be with around 15 separate prototypes produced for evaluation before the final specification was agreed upon. This design remained basically unchanged for a decade and in 1997 a variant appeared in the form of the Valkyrie, with performance-enhancing mods including more radical cam timing and a more efficient exhaust system that gave a worthwhile boost in performance. A completely redesigned front end featured 45mm inverted telescopic forks.

For 2001, a brand new model, the GL1800 (actual capacity 1,832cc) became to standard offering, with an extruded aluminium frame and optional ABS brakes. With the closure of the Marysville plant in 2009, it looked like the end of the line for the Gold Wing, but Honda made the decision to relocate production to Japan at its facility in Kikuchi. After a short hiatus (the remaining US production forming the 2010 model year), production recommenced in 2011, and with the recent Australian release of the new F6B 2013 model, the Gold Wing has survived the test of time.

A local Wing

Malcolm Veale’s GL1000 is an excellent original example of the model that launched the Gold Wing dynasty. It’s a classic case of finally owning the motorcycle that took your fancy many years ago, as Malcolm relates. “Growing up as a young teenager in the early seventies I always had an interest in early mid ‘70s Hondas. Having mini bikes at the time I used to look at these big bikes at the local shop in awe. Like many others in my mid ‘40s I decided to take a keen interest in early Japanese bikes and I have been a long-term member of the Victoria V.J.M.C ever since.

I have had 3 mid ‘70s Honda Fours and I also own a CB750 K1. The Gold Wing has always interested me as this was the first model of this type of motorcycle, and was a complete breakaway from Honda’s previous designs. This bike was a good purchase as it is in original unrestored condition and I do not plan to restore to concourse condition as I quite like the original look of the bike. Hopefully this bike will stay in the family for many years to come.”

Malcolm’s GL1000 came from USA and has now covered just over 36,000 miles. As he says, the bike has a pleasant patina commensurate with its age and it would be a shame to tart it up. Rather, this Gold Wing appears set for a gentle life, enjoying rallies and gatherings where likeminded folk gather, and where Gold Wings rightly occupy a position of power and respect!