An international team of paleontologists from the UK, Italy and Switzerland has created the first digital reconstruction of the skull of Leithia melitensis, an extinct gigantic dormouse that lived on Malta and Sicily around two million years ago.

An artist’s impression of the giant dormouse Leithia melitensis (left) and its nearest living relative the garden dormouse (right). Image credit: James Sadler, University of York.

Leithia melitensis was first described by the Scottish naturalist Andrew Leith Adams in 1863.

Roughly the size of a cat, the ancient rodent is by far the largest known dormouse species, being at least twice the size of other insular species both extant and extinct.

Leithia melitensis is an example of island gigantism, a biological phenomenon in which the body size of an animal isolated on an island increases dramatically.

Alongside the gigantic dormice, the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Sicily were also home to giant swans and owls as well as dwarf deer, hippos and elephants.

“While island dwarfism is relatively well understood, as with limited resources on an island animals may need to shrink to survive, the causes of gigantism are less obvious,” said senior author Dr. Philip Cox, a researcher in the Department of Archaeology and the Hull York Medical School at the University of York.

“Perhaps, with fewer terrestrial predators, larger animals are able to survive as there is less need for hiding in small spaces, or it could be a case of co-evolution with predatory birds where rodents get bigger to make them less vulnerable to being scooped up in talons.”

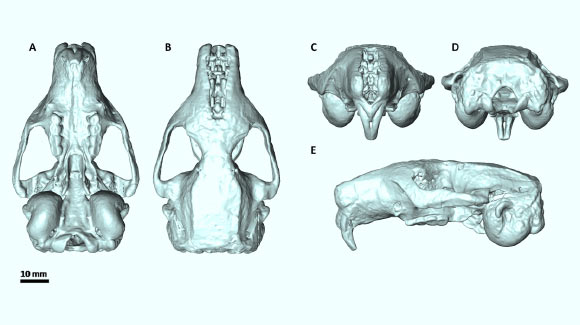

Composite skull of Leithia melitensis: (A) dorsal view, (B) ventral view, (C) anterior view, (D) posterior view, (E) left lateral view. Image credit: Hennekam et al, doi: 10.5334/oq.79.

In the new study, the scientists digitally pieced together fossilized fragments from five skulls of Leithia melitensis to reconstruct the first complete skull of the species.

The reconstructed skull is 10 cm (3.9 inches) long — the length of the entire body and tail of many types of modern dormouse.

“Having only a few fossilized pieces of broken skulls available made it difficult to study this fascinating animal accurately,” said lead author Jesse Hennekam, a PhD student in the Hull York Medical School at the University of York.

“This new reconstruction gives us a much better understanding of what the giant dormouse may have looked like and how it may have lived.”

The results were published in the journal Open Quaternary.

_____

J.J. Hennekam et al. 2020. Virtual Cranial Reconstruction of the Endemic Gigantic Dormouse Leithia melitensis (Rodentia, Gliridae) from Poggio Schinaldo, Sicily. Open Quaternary 6 (1); doi: 10.5334/oq.79