Tsui Hark FAQs: Hong Kong movie director, producer and screenwriter’s career highs and lows, and how he fell out with John Woo

- He didn’t discover Jet Li or Brigitte Lin, but he made them martial arts movie stars; and it was Tsui who urged John Woo to make breakout film A Better Tomorrow

- As a director, Tsui made memorable films including Once Upon a Time in China, and shook up martial arts filmmaking, but some of his early movies were comedies

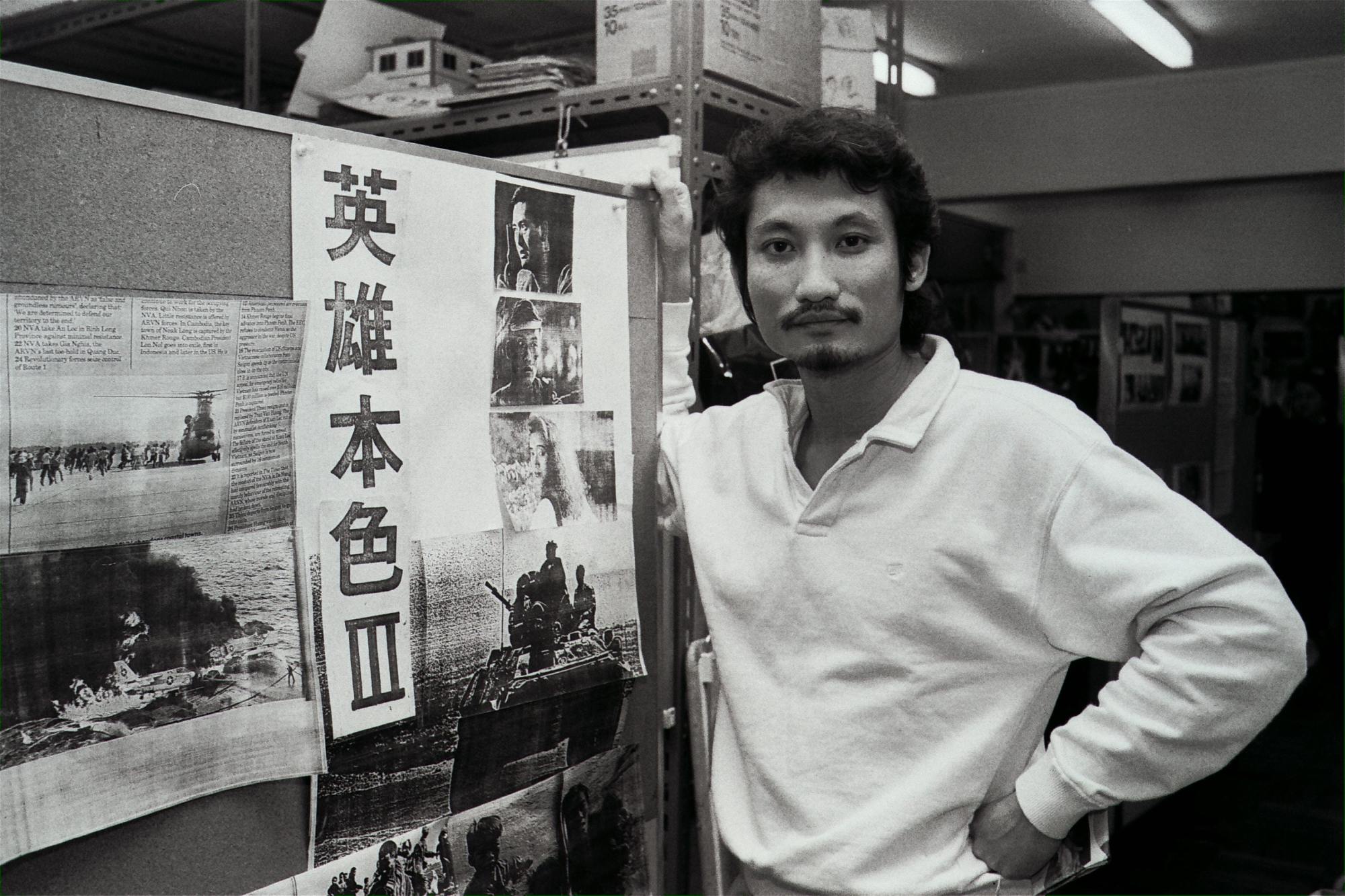

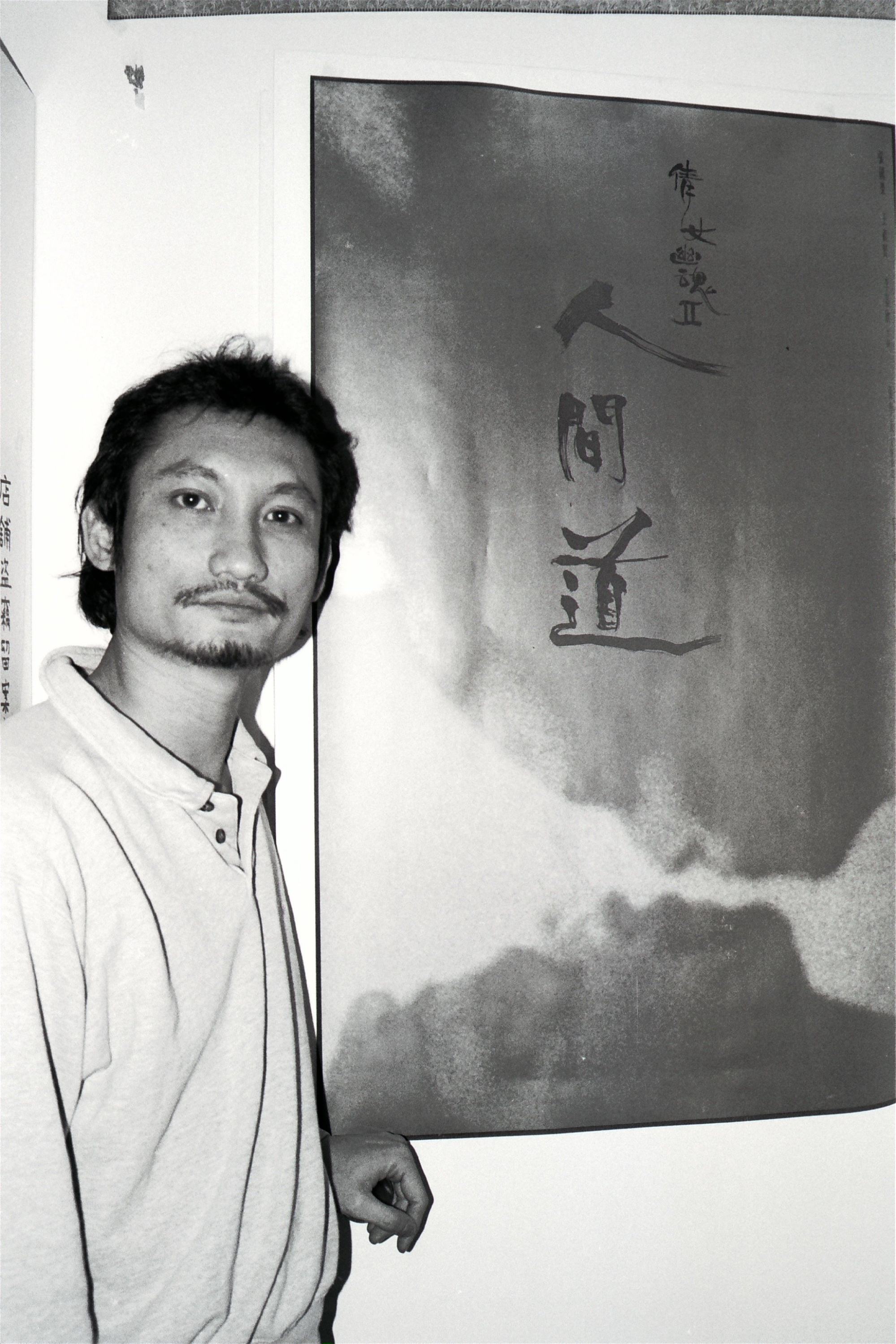

Innovative, energetic, and incredibly hard-working, Tsui Hark was a powerhouse behind the Hong Kong cinema boom of the early 1990s.

We answer some frequently asked questions about the legendary director behind such classics as Peking Opera Blues and Once Upon a Time in China.

Was Tsui born in Hong Kong?

No, Tsui was born in Guangzhou, in southern China, and was brought up in what was then Saigon in Vietnam. He came to Hong Kong when he was 14 for his schooling, and later went to the United States to study at the University of Austin in Texas.

His father, a pharmacist, wanted him to become a doctor, but he didn’t want to follow that path. “I didn’t know what to study, so I chose film,” he told City Entertainment.

He shot some documentaries in the US after he graduated, and also worked in journalism in New York. In 1976, TVB’s Selina Chow Liang Shuk-yee, a prime mover behind Hong Kong New Wave cinema, offered him some work – initially, she chose him to direct comedies. His career took off from there.

‘His films have a forthright attitude towards sex’: the movies of Tony Au

Was Tsui’s TV career a success?

Yes. His 1979 martial arts television series The Gold Dagger Romance thrust him into the limelight. “It was suddenly being called the best thing on TV. I had never had that experience of being talked about before,” he told the Post in 2007.

Tsui began making feature films the same year. “It was like opening a door and walking into a whole new world. It was scary,” he said in the same interview.

Is it true that he discovered John Woo with 1986’s A Better Tomorrow?

Not really. Woo had already tasted success in the 1970s while under contract to Golden Harvest, with the Cantonese opera film Princess Iron Fan, and comedies like Pilferer’s Progress.

Tsui’s relationship with Woo was fractious from the start, as he thought Woo’s action scenes should be more realistic – he didn’t understand how the heroes could survive being shot so many times.

They argued badly on the set of A Better Tomorrow 2, which Woo has said is his worst film, and their working relationship effectively ended there.

Is it true that Tsui once made comedies?

Cinema City, which Tsui joined in 1980, had the express intention of making comedies, as it was formed by comics Dean Shek Tin, Karl Maka and Raymond Wong Pak-ming.

Tsui directed the comedies All the Wrong Clues and the Bond spoof Aces Go Places III: Our Man from Bond Street for Cinema City.

“All the movies I’d done before were depressing,” Tsui told Lisa Morton about All the Wrong Clues. “I said, let’s do a silly movie. Let me relax.” After the success of A Better Tomorrow, the company broadened its approach.

Lin had actually been a big star since her early days in front of the camera in Taiwan in 1972. She had moved to Hong Kong in 1984, and become famous for romantically inclined roles in films and TV.

“Lin is widely recognised as one of the most beautiful actresses on the local scene, and her name is guaranteed to attract an audience,” said the Post in 1987.

So did he discover Jet Li with Once Upon a Time in China?

During this time, he went to the US and made his first film with Tsui, the unsuccessful The Master. Golden Harvest had seen Li’s potential and set the production up, but it was a disaster. Li broke his wrist, there were disagreements on set, and Tsui was not happy with Li’s performance.

“Jet doesn’t act the way I expect him to act … I found it didn’t work,” Tsui said. The film was shelved and only released in 1992, after the success of Once Upon a Time in China.

But Tsui is well known for muscling in and taking control away from the director on set, an act that is considered taboo in the film industry. He also dominated in areas that are generally considered the director’s responsibility, such as casting choices and script rewrites.

Ching, who was employed by Tsui because of his innovative approach to fantasy action sequences, was apparently happy with the arrangement, and the fantastical martial arts scenes bear his hallmarks as well as Tsui’s.

Tsui is often mistakenly referred to as the director of those films.

What was special about Tsui’s action scenes?

Although some great martial arts films were made in the 1980s, the genre was not overly popular and was ripe for reinvention.

Why not even Stephen Chow can stop Tsui Hark getting his way

Tsui also brought some of his US filmmaking training to the combat sequences, using fast and varied edits and insert shots to build up a scene, rather than focusing on capturing natural kung fu fighting. He brought back wire work, which had been out of fashion, to simulate flying, and allowed his choreographers to experiment with it.

He also had big budgets at his disposal to make it all look good.

Did Tsui’s films go downhill after the mid-1990s?

After 1995, Tsui often ran into problems getting big enough budgets to realise his ambitious ideas, and the overall quality of his work declined. The special effects in 2011’s below-par Flying Swords of Dragon Gate suffered because he ran out of money to pay for them, for instance.

But there have been successes like the wuxia Seven Swords, and the slick and clever contemporary actioner Time and Tide, which is one of his best works.

Tsui’s excursions into mainland China to make propaganda films have done little to restore his stature in Hong Kong.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.