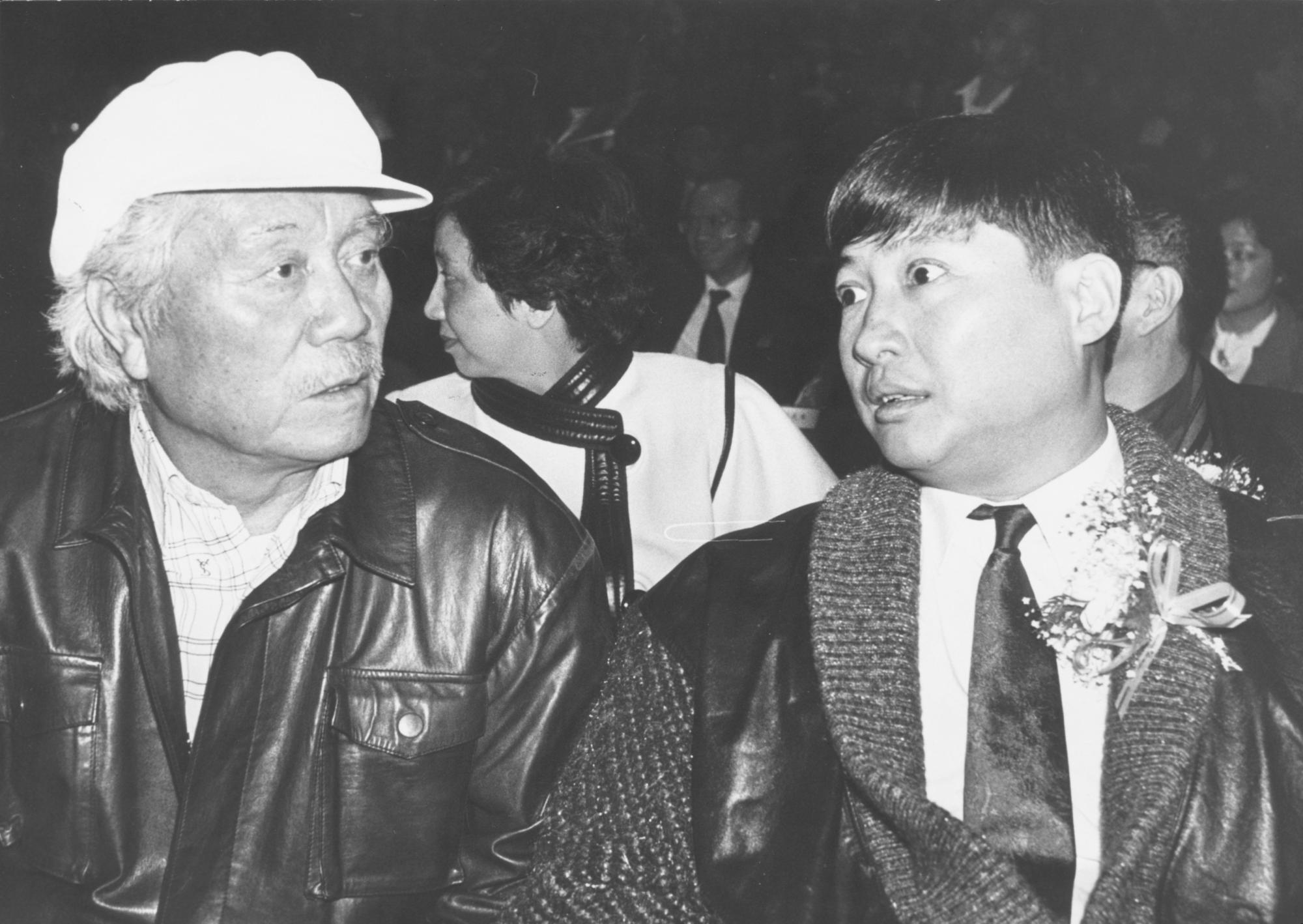

Sammo Hung: from being Jackie Chan’s boss to honing Michelle Yeoh’s talent, 8 little-known facts about the Hong Kong martial arts star

- Sammo Hung has been a force in Hong Kong cinema for decades as an actor, producer and martial artist. But how much do you know about him and his career?

- Hung was a full-time stuntman by the time he was 16, having largely taught himself kung fu, before moving into acting – from which he later walked away

Sammo Hung Kam-bo has been a powerful force in Hong Kong cinema since the 1960s. You may think you know all there is to know about the prolific actor, producer and martial artist, but here are a few lesser-known facts about Hung.

1. Hung came from a moviemaking family – is that why he went into films?

According to an interview that Hung gave to the Hong Kong Film Archive, his maternal grandfather used to build film sets in Hong Kong, and his paternal grandfather Hung Chun-ho was a big producer who once had his own studio in Kowloon, but lost it gambling on the horses.

‘This is it’: the 90s film set on which Michelle Yeoh was seriously injured

Hung’s parents both worked in film wardrobe departments.

Hung lived with his grandparents, but has said that their involvement in the movie industry had no influence on his later film career.

When he joined the China Drama Academy, a Peking opera school, as a child, he had no thoughts about going into movies, he has said, noting that he was sent to study opera as he was not good at regular school.

2. Did he learn his kung fu at the China Drama Academy?

Like most martial artists who began at opera schools, Hung trained himself in specific martial arts styles after he left.

Hung’s time at the school was, unsurprisingly, focused on opera, and he started as a qingyi, or young supporting female, and then moved on to young scholar roles. When his voice broke at 14, he changed to “posture painted face” roles which concentrated on fighting rather than singing.

“Since my voice wasn’t too good, I mainly focused on ‘posture painted face’,” he told the Film Archive.

Sammo Hung’s 10 best films ranked, from Pedicab Driver to Ip Man 2

Yes, he did.

Hung appeared in his first film, Education of Love, in 1961 and began working as a stuntman while at the Academy, at the age of 14. A couple of years later, Hung was working as a stuntman full-time.

“Sammo was working before me and Jackie,” Yuen Biao, another alumnus of the China Drama Academy, said in an interview. “Jackie and I worked for him when we started out. For a while, I worked for Sammo as assistant action choreographer.”

4. Did he get injured early on in his career?

Injuries are all part of the job. “He nonchalantly told me he had broken his legs about seven times while working as a stuntman for Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest,” Post journalist Cherry Mostehar wrote in 1982.

Why martial arts films owe so much to Chinese opera

“He said that there was not a part of his body that had not been injured during his 14 years as a stuntman and actor.”

“I’ve got used to it,” he told the Post. “After a while it becomes easier to avoid really bad injuries, although it is difficult to avoid doing dangerous things.”

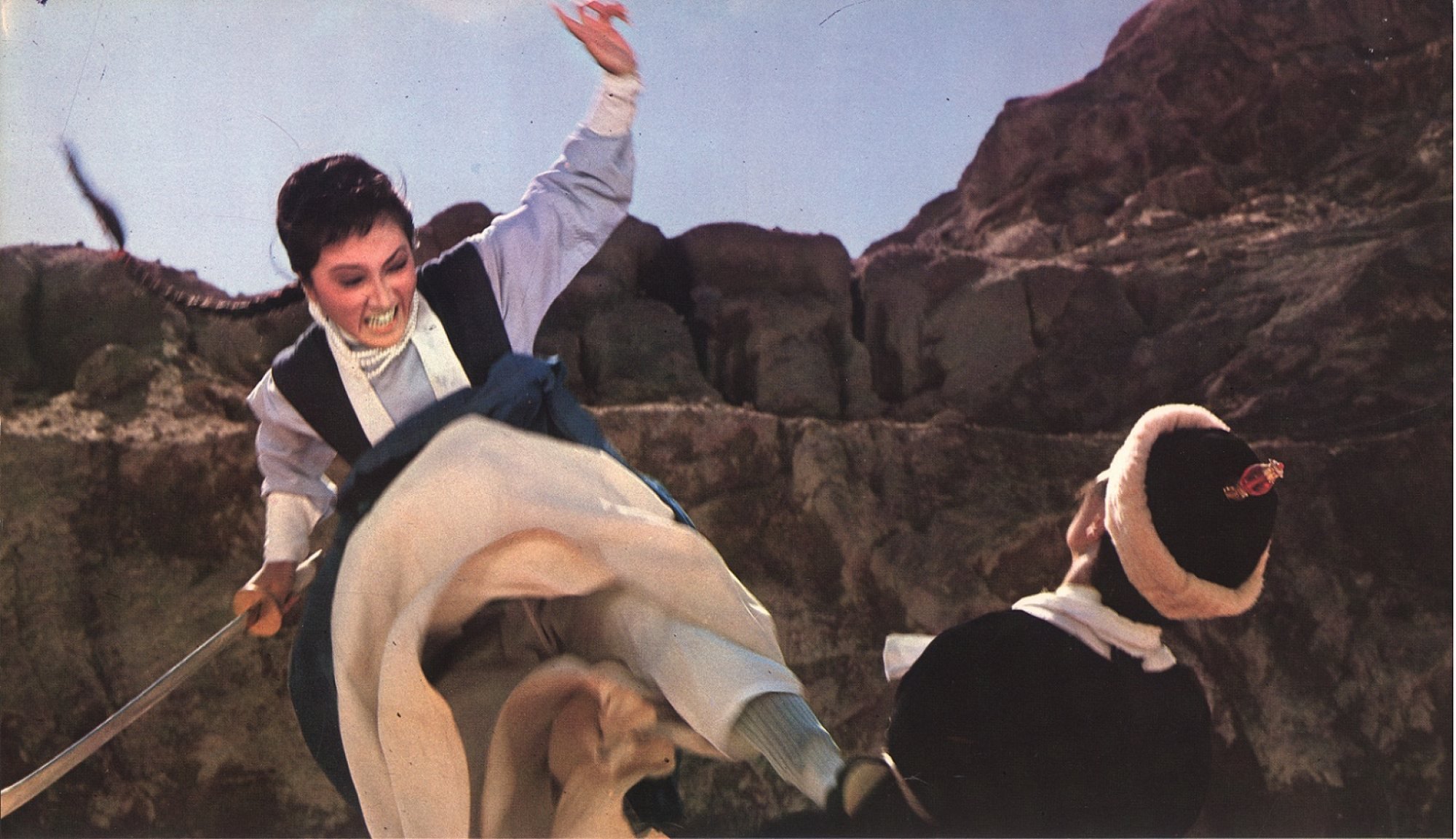

5. Did he really choreograph action scenes for the philosophical director King Hu?

Legendary martial arts director King Hu always knew what he wanted in a shot, but he had no knowledge of martial arts techniques, and relied on his martial arts directors.

“King Hu was like an uncle, but more. It’s a really hard thing to explain just what I learned from him because there was so much,” he told film journalist Mathew Scott.

“I would always go to his house and then I would talk to him about life, about philosophy, about society, about everything. At 5am he would shut down his home and we would go off and start making films.”

6. What is his signature martial arts style?

Hung doesn’t really have a signature style, being adept in many.

7. Is it true that he was a big studio boss?

A super-producer might be a better designation. Hung’s company Bo Ho – which used the last part of his Chinese name – was actually a subsidiary of Golden Harvest, where Hung served as a producer, and was founded in 1980.

Hung’s main claim to studio fame came when heS co-founded D & B Films in 1984 with businessman Dickson Poon – the B in the name again stands for Bo.

When D&B launched its own cinema chain, Golden Harvest felt there was a conflict of interest. Hung quietly abandoned his new company and reverted to working for Golden Harvest full time around 1985.

Hung’s early Gar Bo Films, and his later Bojon Films were not major players.

Sammo Hung film launched a genre and made him a player

8. Why did he miss out on the martial arts boom of the 1990s?

Hung acrimoniously resigned from Golden Harvest in 1991, claiming that the company was no longer supportive of him. He has said he felt disillusioned with the film industry and didn’t want to work.

Furthermore, his down-to-earth style was at odds with the wirework and special effects that defined Hong Kong action cinema in that decade.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.