DISCLAIMER: I didn’t go to a lot of trouble to make this accessible to someone who hasn’t read any of Shirow’s work before, so apologies if it’s a bit insidery – there was so much to write about, I didn’t always take the time to contextualize characters and recap plots. I’m hoping I cut away more fat than lean... but your mileage may vary.

-Tom Herpich, June 2021

* * *

I find Shirow fascinating – he’s a genuine comics enigma. Not only is he a borderline Salinger-esque recluse (“Shirow Masamune” is a pseudonym), but he also took an almost literally inexplicable mid-career zag from genius-on-high-at-the-pinnacle-of-his-career to tasteless pornographer, almost overnight. On top of that, his work is a puzzle in itself. It’s an electrifying, exasperating mix of thrilling genre satisfactions and extremely dense, demanding, user-unfriendly storytelling. It’s hard to think of any popular entertainment with so little narrative handholding. Characters go about their technologically or strategically intricate business without any exposition (or else with exposition that’s only slightly less complex and user-unfriendly than what it’s supposed to be clarifying). But all that headache-inducing confusion is part of the draw: you spend a lot of time fumbling, but when an insight dawns and you get on his level for a second, it’s extremely satisfying – it’s like a magic eye puzzle, where you’re staring at it forever until suddenly it comes into focus and it’s been there the whole time (plus, unrelatedly, there’s a sort of thrilling verisimilitude that comes from not fully understanding a narrative that I’m reading: it feels more like real life. Too much clarity erodes my suspension of disbelief...). But it’s a subtle balance: you get rewarded for thinking hard about his stuff, but then you get punished for it too, because there’s a lot of it that I think is just not going to compute to anyone but him; it’s a private conversation going on in his head, a puzzle with missing pieces. And you’re never sure where the line is. But man, the drawings... I feel like Appleseed Book 3 is where it all bursts open, and the work is just pure pleasure to look at. And then his style keeps getting more and more interesting until Ghost in the Shell 2, which straddles the line between his impeccable comics work and the tasteless digital sleaze that followed. It’s one of comics’ greatest mysteries! It almost keeps me up at night, wondering what happened. I can’t square it with what I know about every other artist (myself included) besides him... it’s like seeing a UFO or something – I can’t fit it into my worldview. The explanation that he’s given for simultaneously abandoning several major projects midstream is that he lost all his notes and reference materials in the '95 Kobe earthquake, which sort of explains the stories getting abandoned, but not the drastic change to his whole approach and aesthetic. Intricate narratives gave way to collections of pornographic illustrations, and his masterful ink and paint techniques gave way to forever-amateurish-looking, perpetually-unintegrated digital techniques that his old fans still gripe about 20+ years later.

I stumbled onto Ghost in the Shell when I was probably around 16 or 17, only a year or two after I’d started reading comics at all, and was totally, obsessively fascinated. Some of my most sparkling, nostalgic childhood memories are of sitting on the edge of my bed, absorbed in Ghost in the Shell, or THB, or Acme Novelty Library – right at the cusp of a lifelong passion. So when I first finished reading GitS, I did my research and discovered Appleseed, Shirow’s next most famous work, and bought the first volume, but hated it (it’s a way earlier, much less polished work), and my obsession ended there. Over the years I read Orion and Ghost in the Shell 1.5, and some other odds and ends, but that’s about it. I stayed a fan, but mostly just from inertia after that first Big Bang.

Stuck inside during these past 10 months of quarantine, I started reading way more comics than usual (and I usually read a lot). It’s been about the closest I’ve felt since college to actually “being a kid again”. And somewhere in there I decided to read/reread all of Shirow’s pre-1998 comics work, and record my impressions of it. It was two fun projects in one, with a bonus third project, which was hunting for deals on out-of-print books online. An almost* perfect quarantine occupation (*it did start to drag a bit towards the end).

At any rate, this is what I ended up with, in chronological reading order.

* * *

ORION (1990-91) - translated by Frederik L. Schodt & Toren Smith

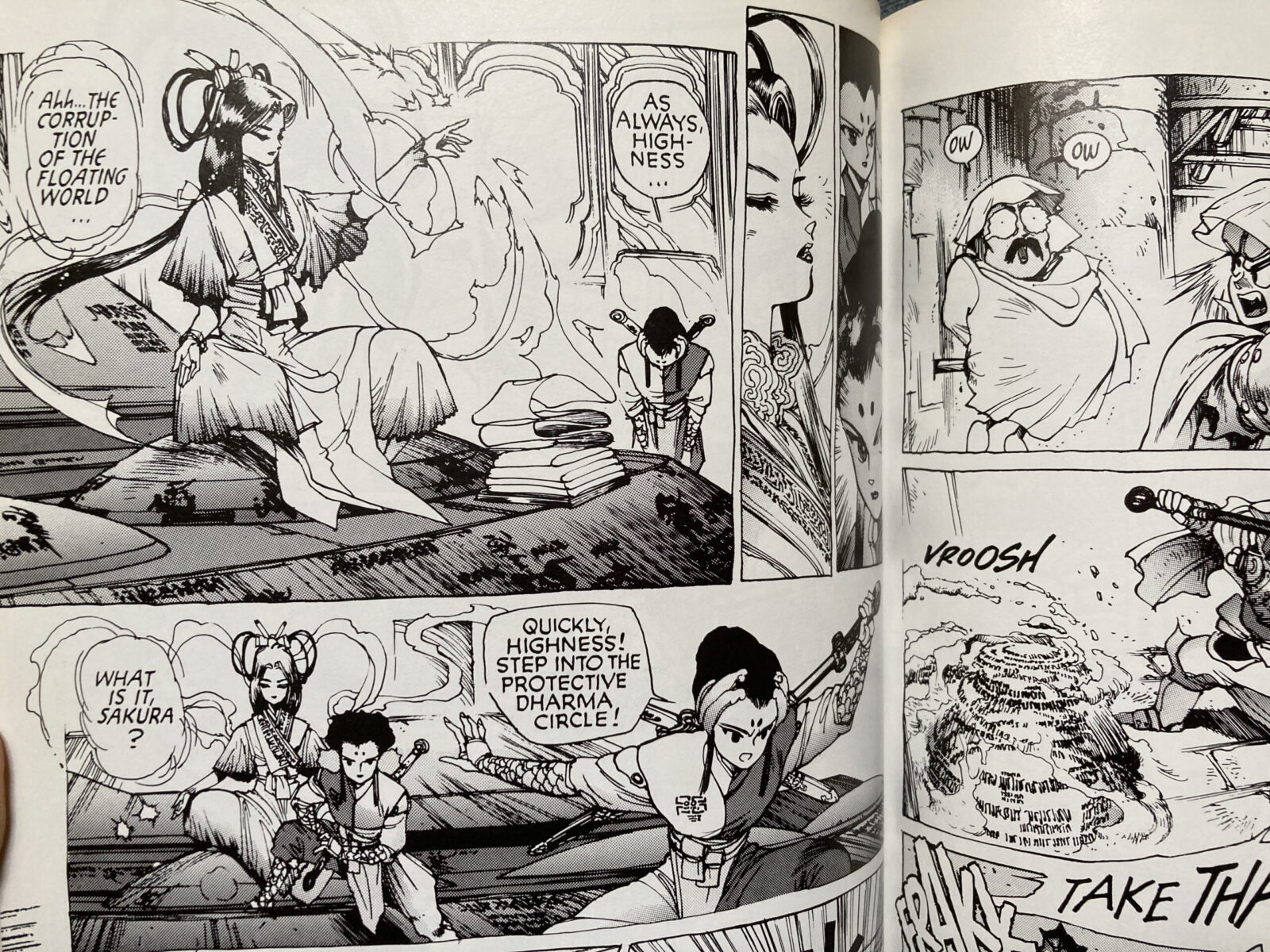

This one is so hermetically inscrutable that it’s borderline outsider art, yet at the same time is also the work of an absolute master in peak form, crafting what, from a certain angle, feels like a series of fairly straightforward action movie beats. He’s obviously smart enough to realize that no one reading this book could follow almost any of the dialogue... but he treats you like you understand all of it: even the explanatory footnotes he puts in end up functioning as just more nonsense patter – seemingly premised on you already understanding things you definitely don’t understand. As you read what I’m writing here, and if you haven’t read the book, you might be picturing all this nonsense being written in an artful, self-aware way – but when you’re actually reading it, it doesn’t feel that way at all. It feels like it was written in a different dimension, with different schools and different curricula, and a whole different set of assumed baseline knowledge in its audience (some of this must be actual cultural differences between the US and Japan, but I get the feeling it’s not a lot). Super, super strange reading experience... I kept wondering what was in his mind as he made it, and couldn’t come up with much. It puts me in mind of Miura’s Berserk a little bit (in a meta sort of way, not a story way), which is another disconcerting reading experience. Berserk is so novel partly because you wouldn’t expect such a nasty, misanthropic piece of media to be crafted by such a massively gifted entertainer. The discord gives it extra juice. Instead of something dark, though, Orion has a massively gifted entertainer making something hopelessly private and opaque. The pairing of extreme accessibility and maybe-unprecedented inaccessibility is really jarring and strange. Visually, it’s really inky and calligraphic, and really nice looking on glossy paper. They’re very pretty “page-as-object” pages. And, while the inaccessibility is frustrating, it’s not frustrating the way it is in something like Ghost in the Shell, since in Orion you know you’re nowhere near understanding what anyone’s talking about, so you’re not really sweating it, whereas in the political-thriller/police procedural stuff I always feel like I might actually have all the puzzle pieces I need, but I’m not smart enough to tell one way or the other. In Orion you’re pretty clearly missing the Rosetta Stone... I think???... Or are you???... I’ll admit I did still, while reading it, get the occasional flash of “am I the only one who doesn’t get this?”...

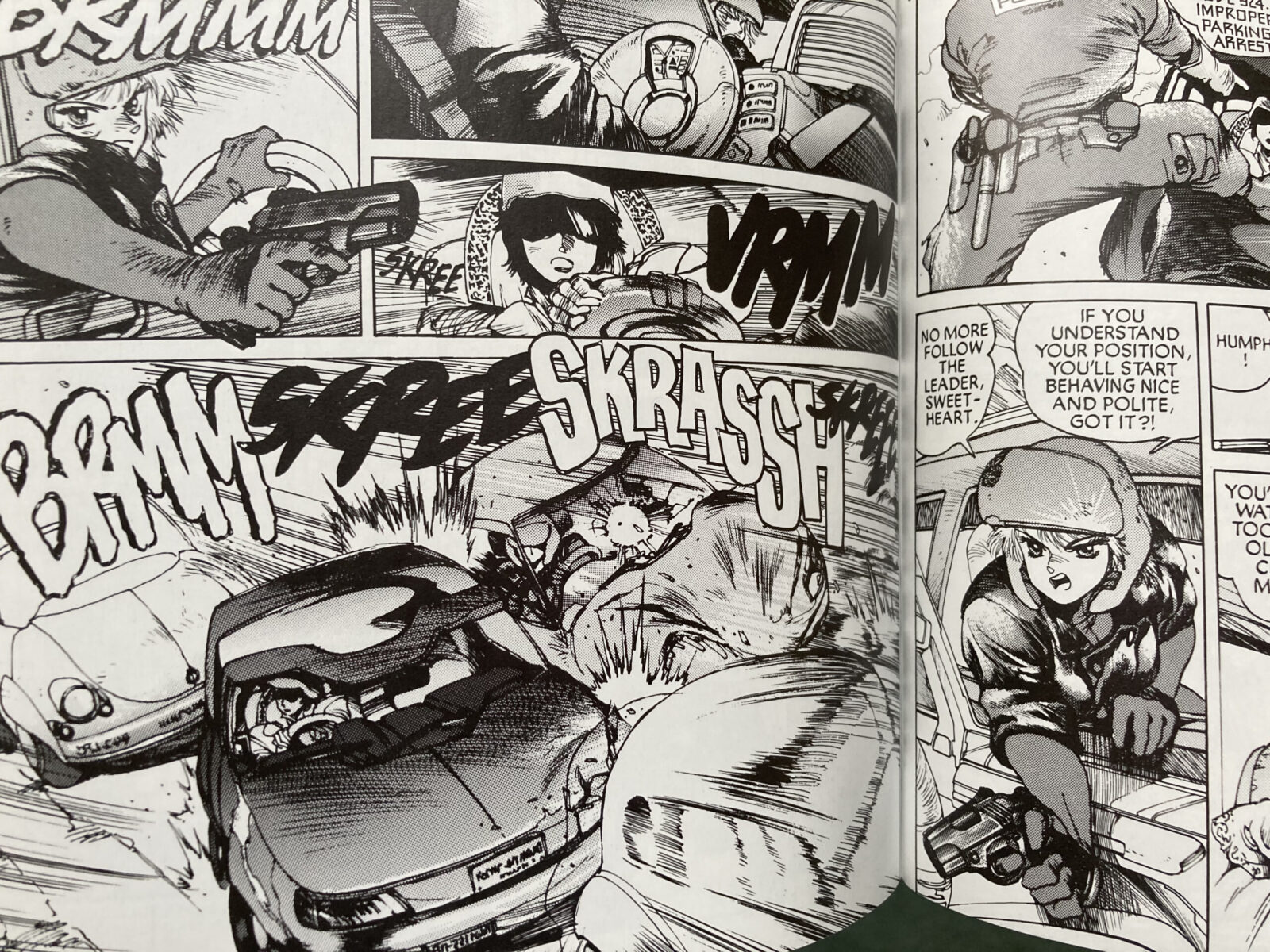

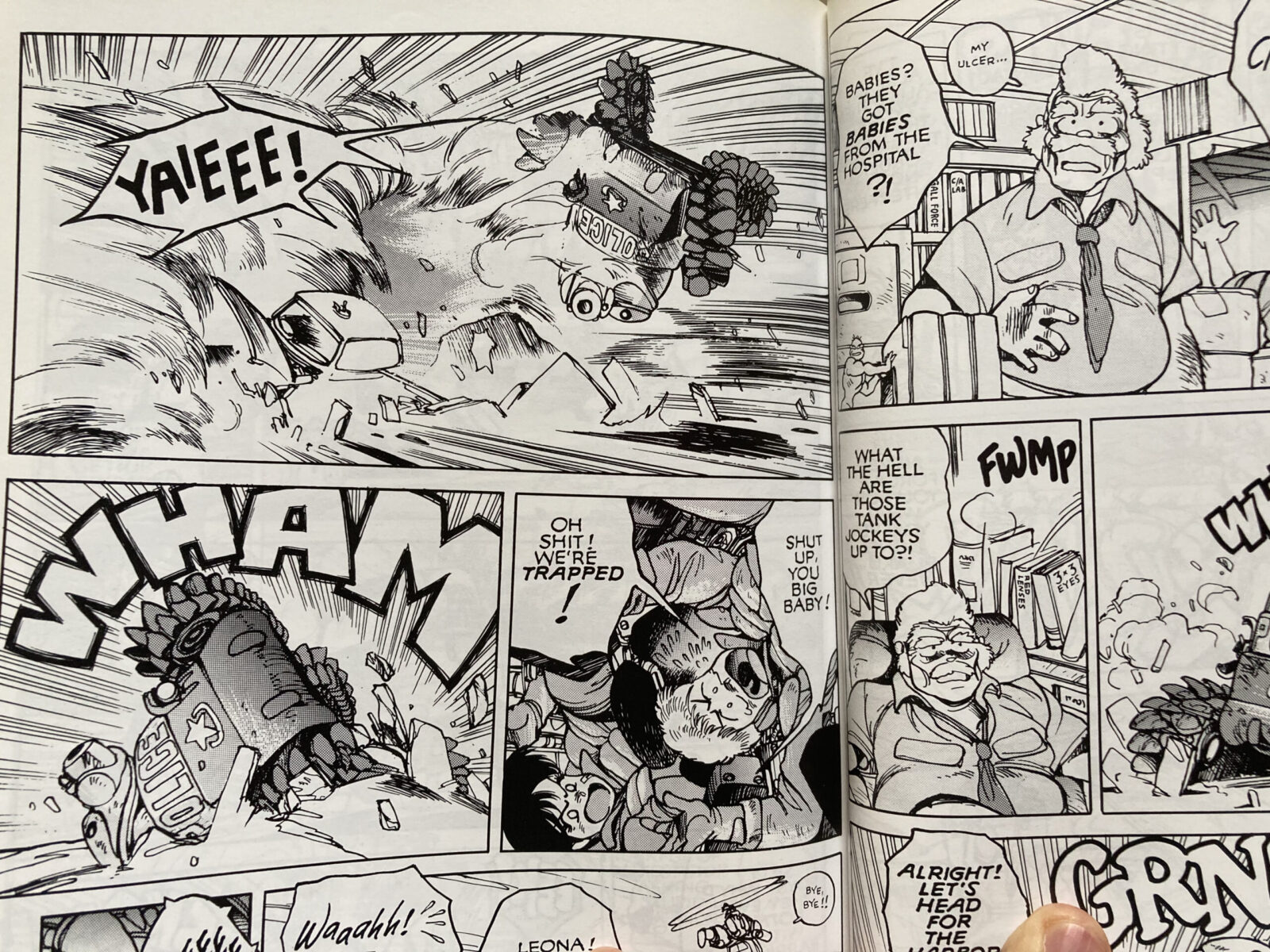

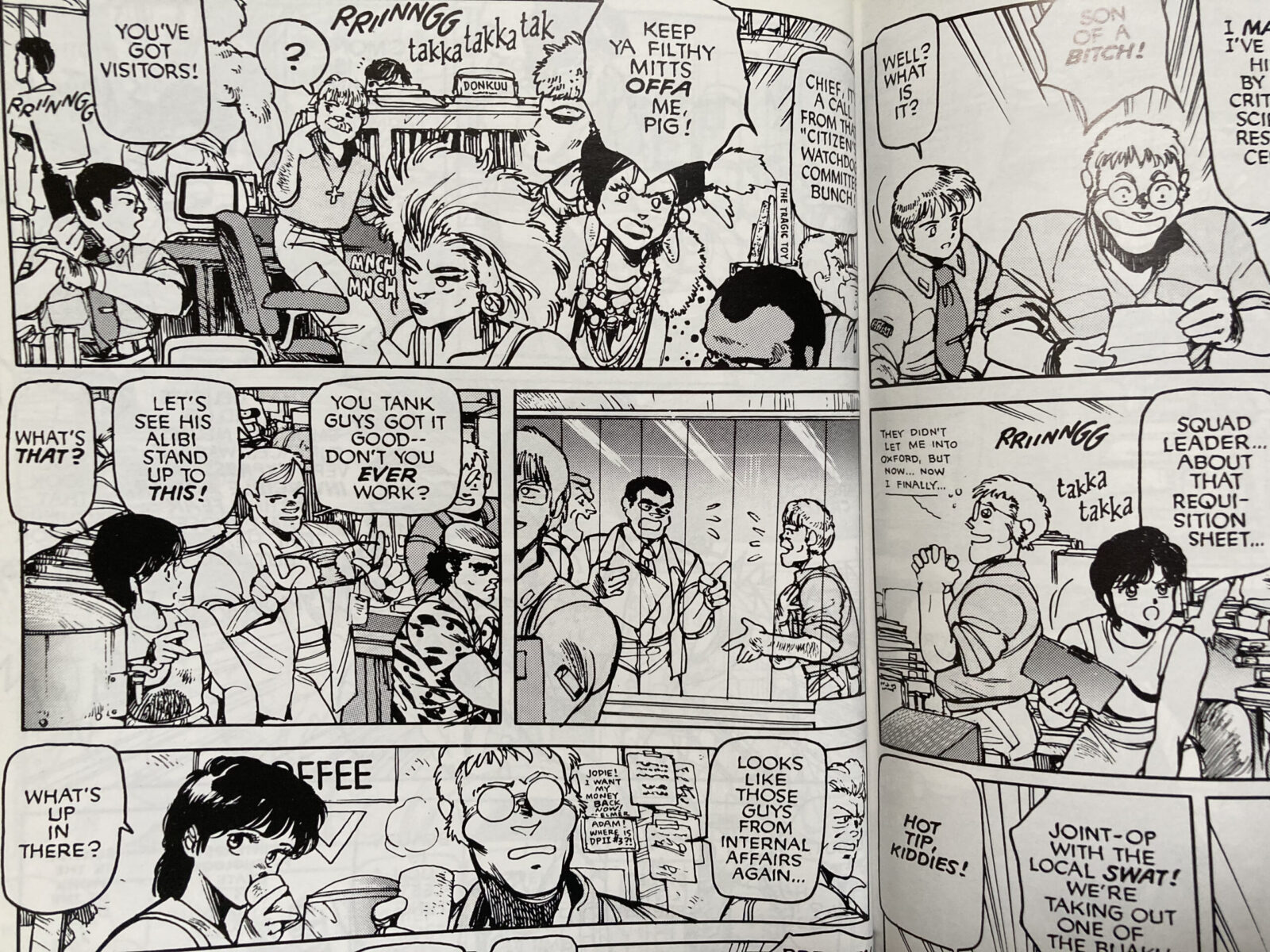

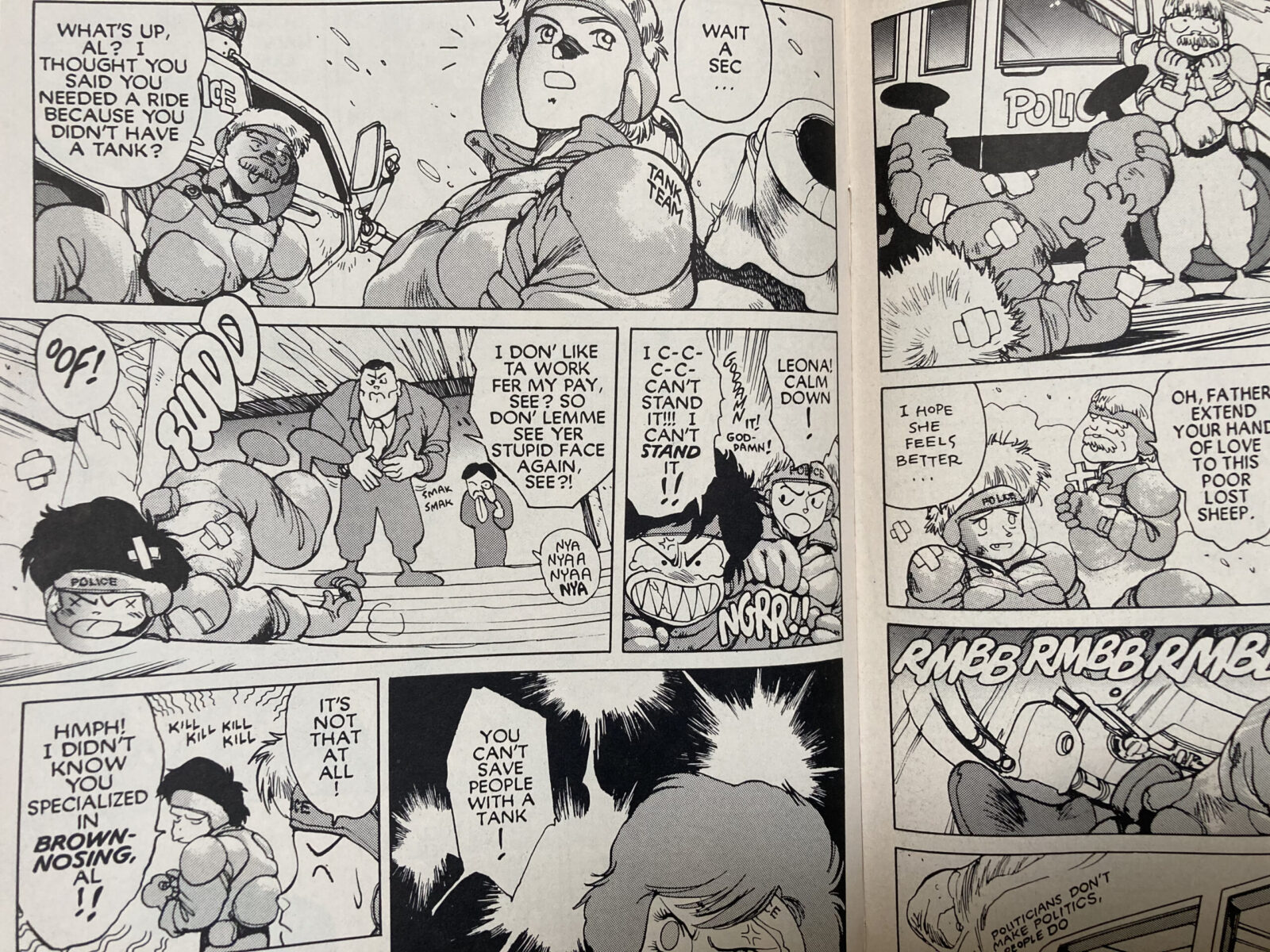

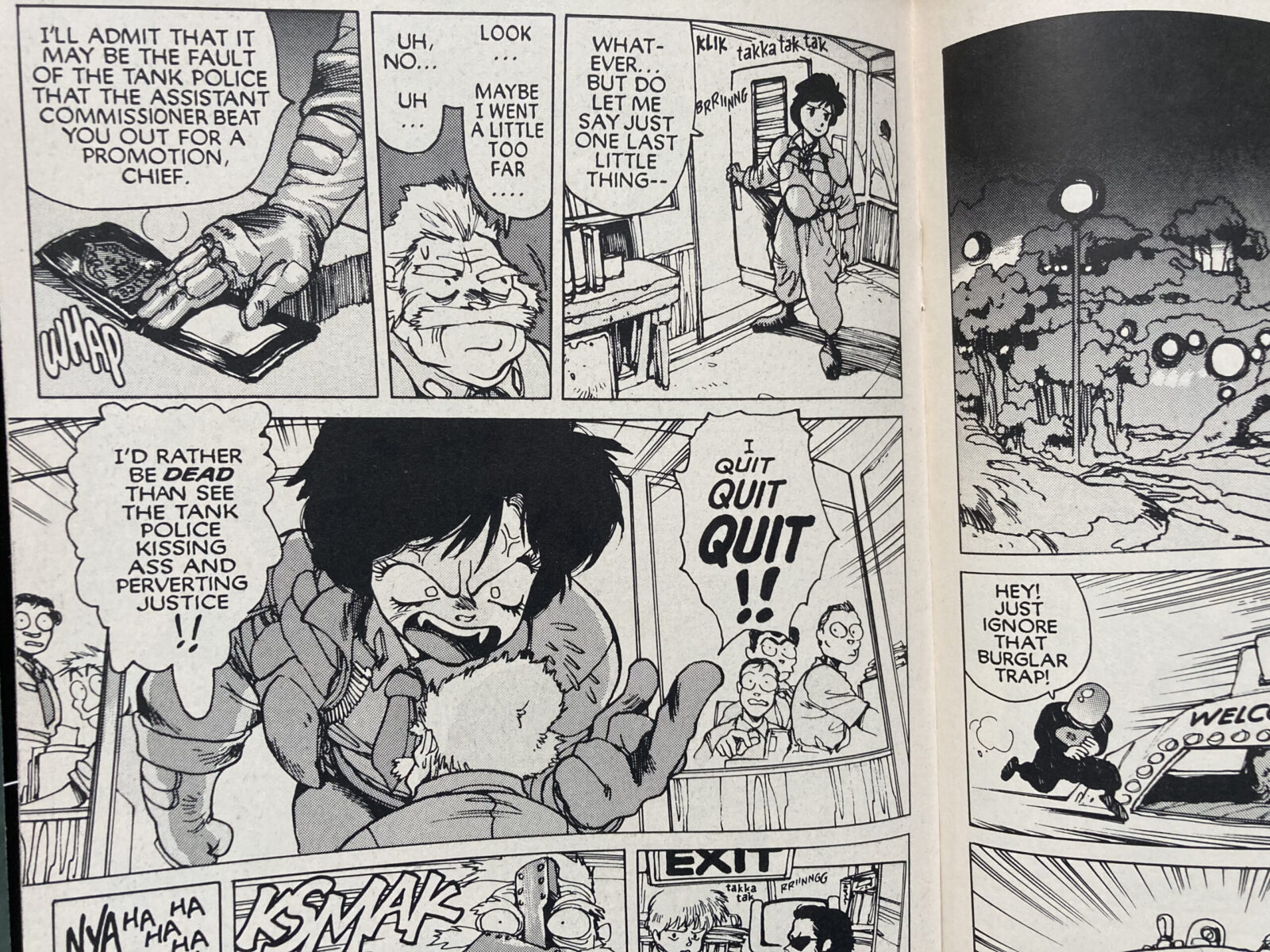

DOMINION: CONFLICT 1 [NO MORE NOISE] (1992-93) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

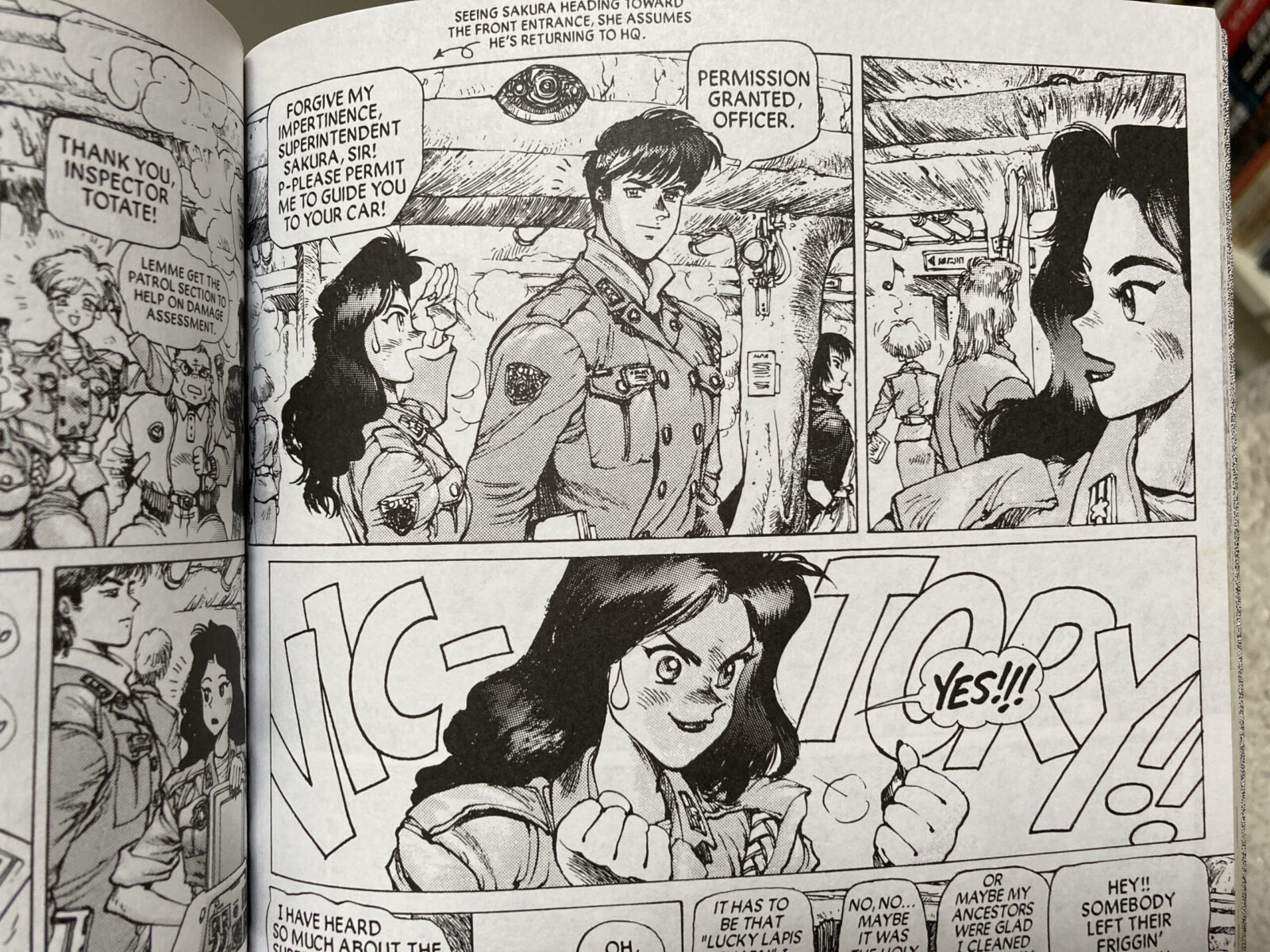

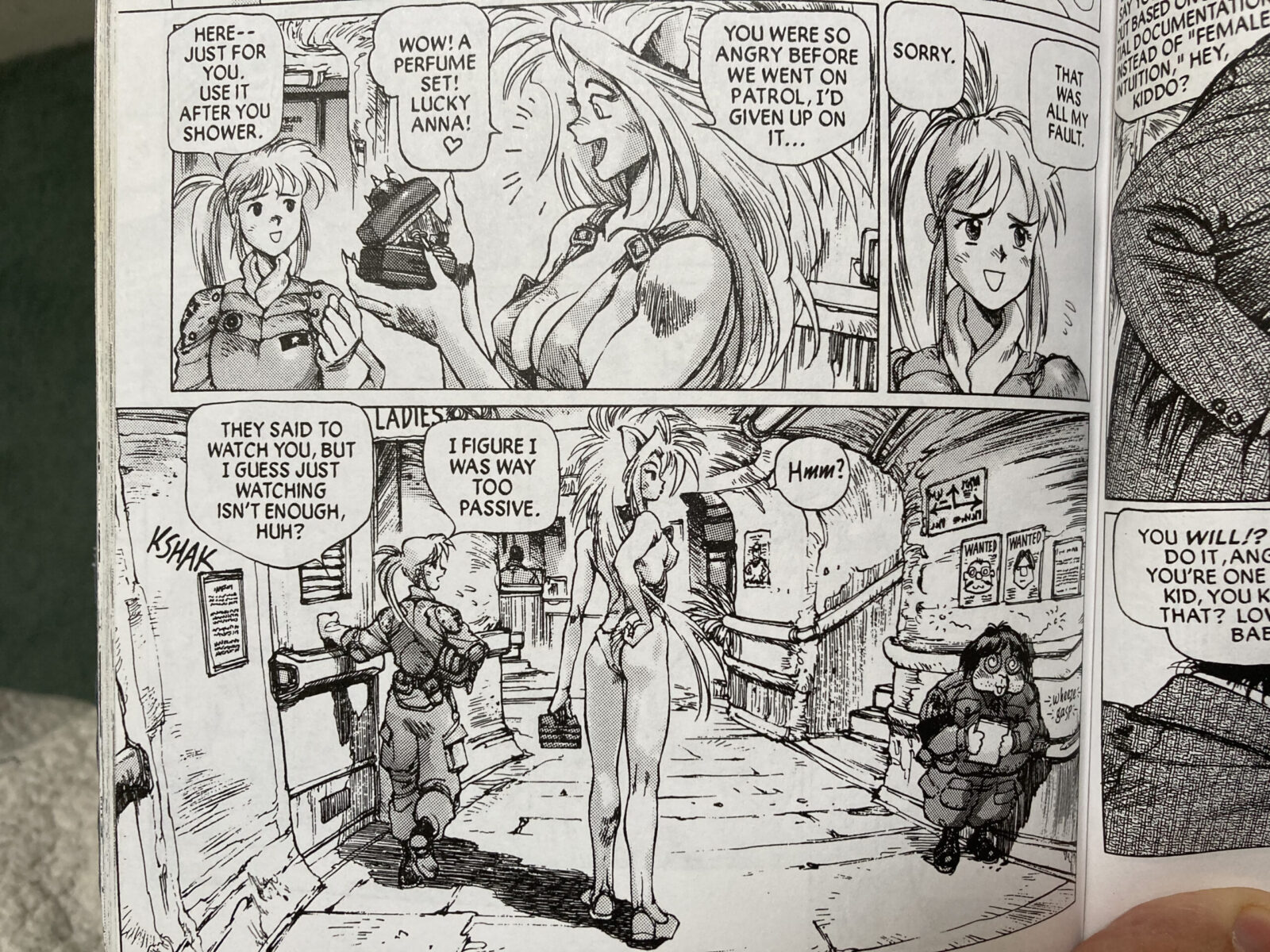

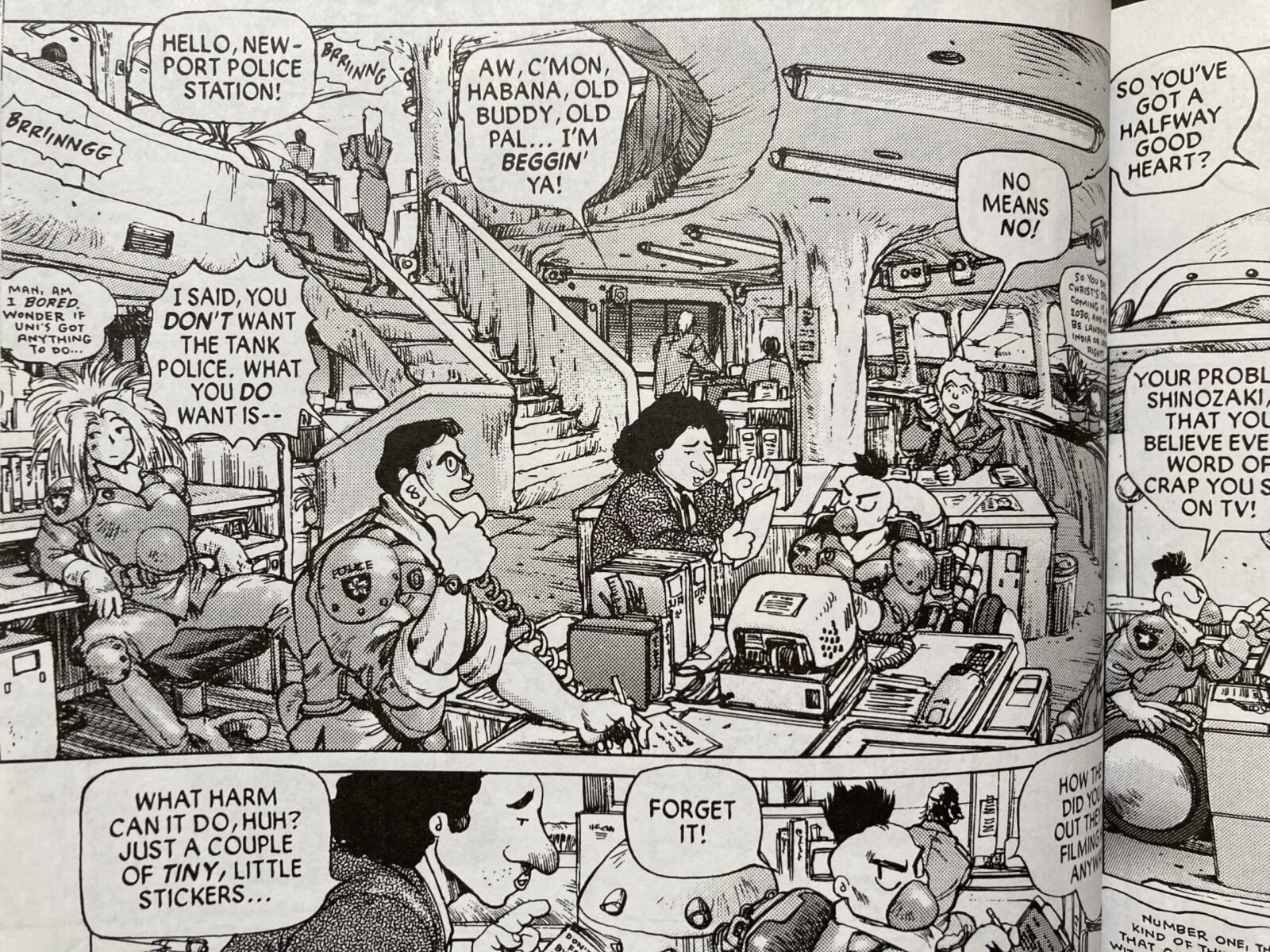

This one is EXTREMELY accessible and entertaining, even by non-Shirow standards. I was very pleasantly surprised – shocked even. I didn’t know he had it in him. Maybe about 1% of the dialogue/events were opaquely confusing – but on balance this was a model of information management. There’s always 3 or 4 different storylines playing out in the background of any scene, all confidently dribbling out at a leisurely pace throughout the book, and it’s all really warm and fun and smart – it’s like an episode of ER, but about a police station, and really funny, and with an amazing action sequence at the end. His drawings are in really great form – they’re almost a little too lush and pretty to read easily, but just basking in the care and affection of the craft more than makes up for it. I think this was pretty much his last major completed work before the bafflingly sharp turn towards the repellent (i.e. Ghost in the Shell 2), which is even more of a bummer now that I realize what great shape he was in right up to the end. The goofy sky pirate stuff put me in mind of Miyazaki’s films, which is interesting since what little I’ve read about the preceding Dominion series (the poisoned air stuff) put me in mind of Nausicaä in particular. Also: the back page of this collection mentions 3 more planned Dominion: Conflict volumes, none of which ever happened.

APPLESEED BOOK 1: THE PROMETHEAN CHALLENGE (1985) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

It’s hard going from peak Shirow to this, which is some of his very earliest work. You can see all the signs of what’s to come, but in a vacuum it’s not especially impressive. The plot has more conventional characterization than his later stuff and unfolds in a more conventional way, and so is more conventionally satisfying in spots, but the story is pretty confusing and I didn’t care enough to try very hard to figure it out (plus Shirow at his best transcends conventional satisfactions, so it’s kind of a mixed blessing to encounter them in his work at all). I couldn’t really tell which political factions had what motives and why – though I sometimes feel like I’m unusually dense when it comes to this kind of political intrigue storyline, so your mileage may vary. In particular I couldn’t tell if the group of old men that we keep cutting to are “the council” that we keep hearing about, or a subset of a larger “the council”. It was more frustrating than it probably sounds. (The Appleseed Databook (a reference guide which I’ll get to later) doesn’t make any mention of any “council” at all – but refers to the old men as the “legislature”...). Also, the big climactic action sequence at the end of the book is so confusingly staged and drawn that it’s mostly just page after page of white noise. It’s dozens of mechs fighting and chasing each other around and they all look pretty much the same – and the backgrounds are so limited that you never have much of an idea of where things are or what you’re looking at, or even what angle you’re looking from. It was a slog. This one left me so cold as a teenager that all the obsessive Shirow enthusiasm I’d built up via Ghost in the Shell totally evaporated and didn’t come back in full until now, 20 years later.

APPLESEED BOOK 2: PROMETHEUS UNBOUND (1985) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

It’s kind of magical to watch everything that was annoying about the first volume slowly, almost imperceptibly gradate towards its more mature, entertaining form, but it’s definitely not there yet, and this was still kind of a slog. There’s a lot of nice, authentically complex feeling, elliptical dialogue - but actually trying to parse the political and philosophical content made my brain glaze over, and gave me that Shirow-specific itch, where I can’t quite tell if he’s giving me enough information to figure out what’s going on, and so I end up not wanting to risk wasting the brainpower on an attempt if all the pieces are potentially not there. I guess the short version is: I didn’t really care enough about this story to think about it very hard. I’m wondering if when I was 16 I was more content to let this kind of philosophical technobabble stuff just wash over me unchallenged, but even back then I found Appleseed Book 1 totally uninteresting, whereas Ghost in the Shell, (which I haven’t reread yet, but I think is at least equally permeated with opaque technobabble) was profoundly, formatively captivating. Is it just that the art in GitS was so beautiful that I could love it in spite of its headachey story? From having flipped through the next two Appleseed volumes, I feel like number 4 is visually about on par with GitS (and 3’s not too shabby either), so I guess I’ll find out.

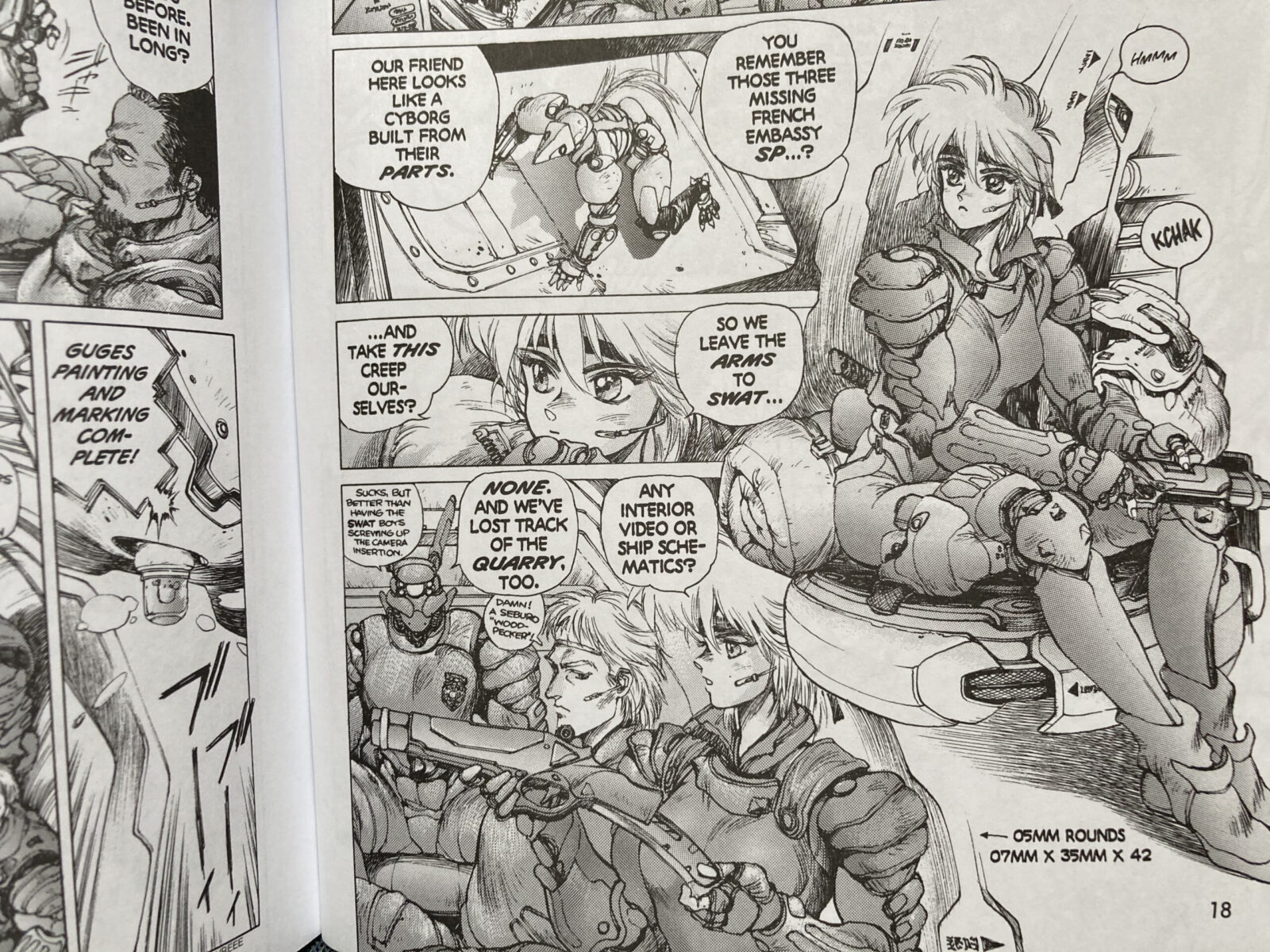

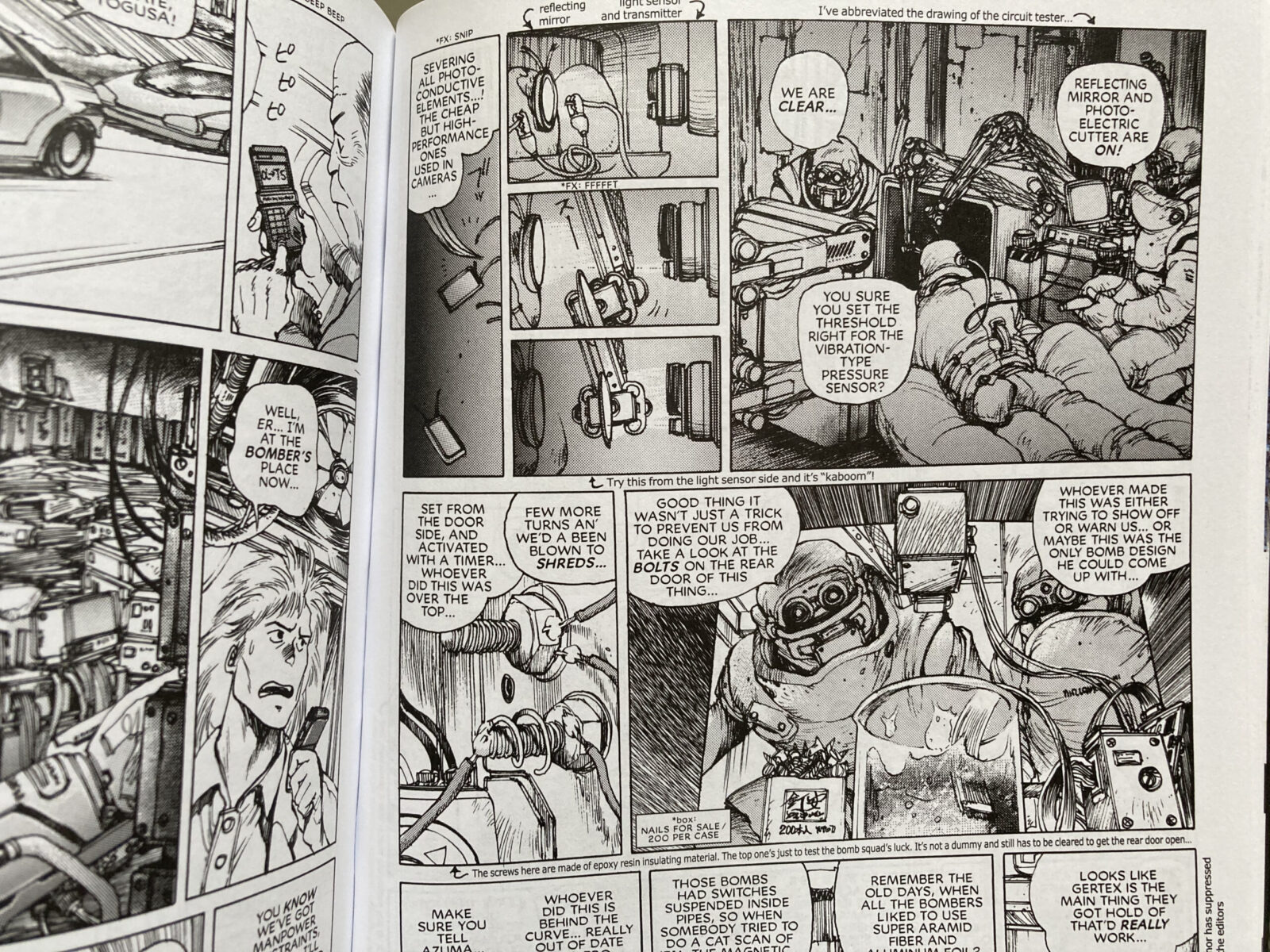

APPLESEED BOOK 3: THE SCALES OF PROMETHEUS (1987) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

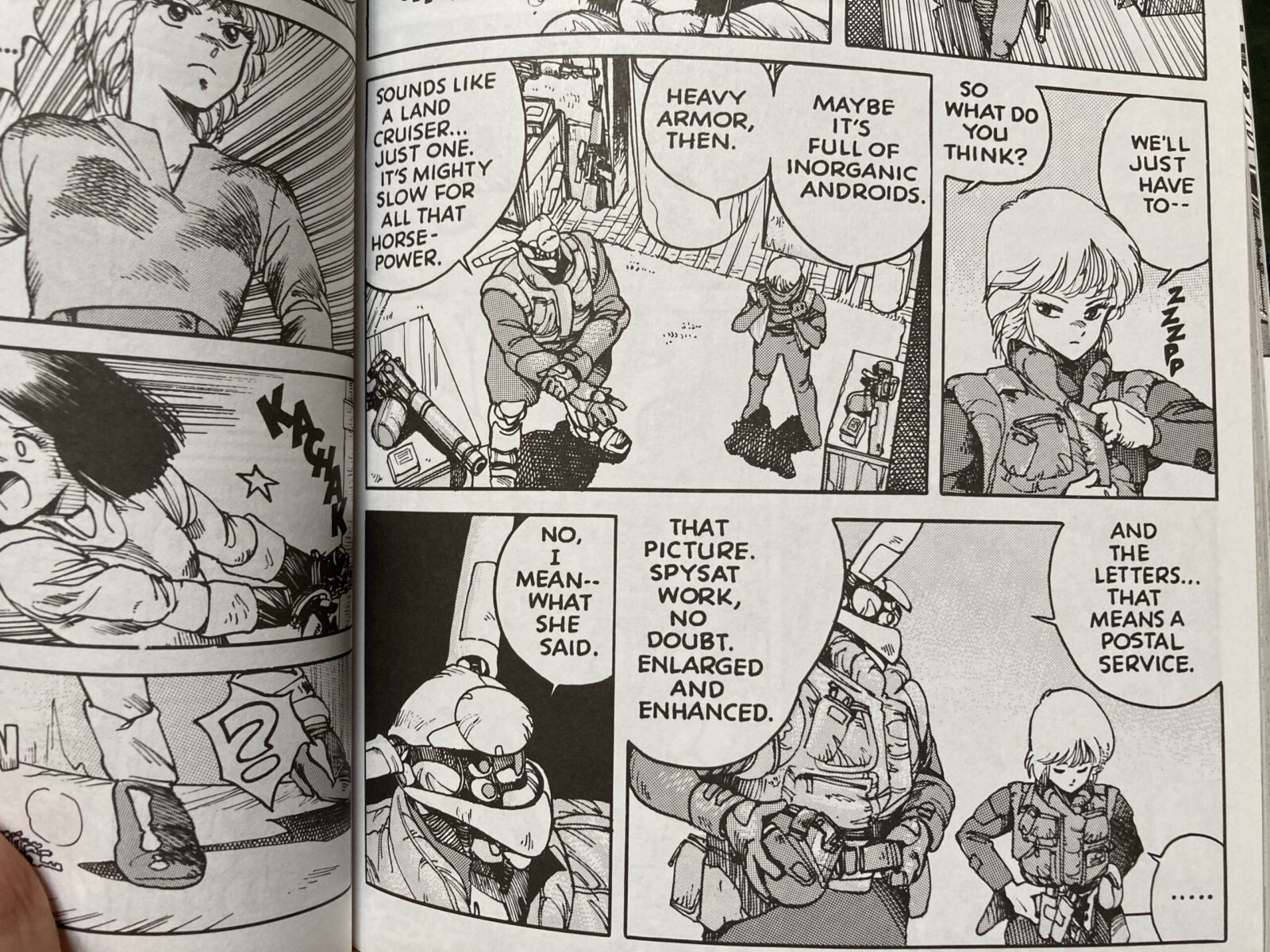

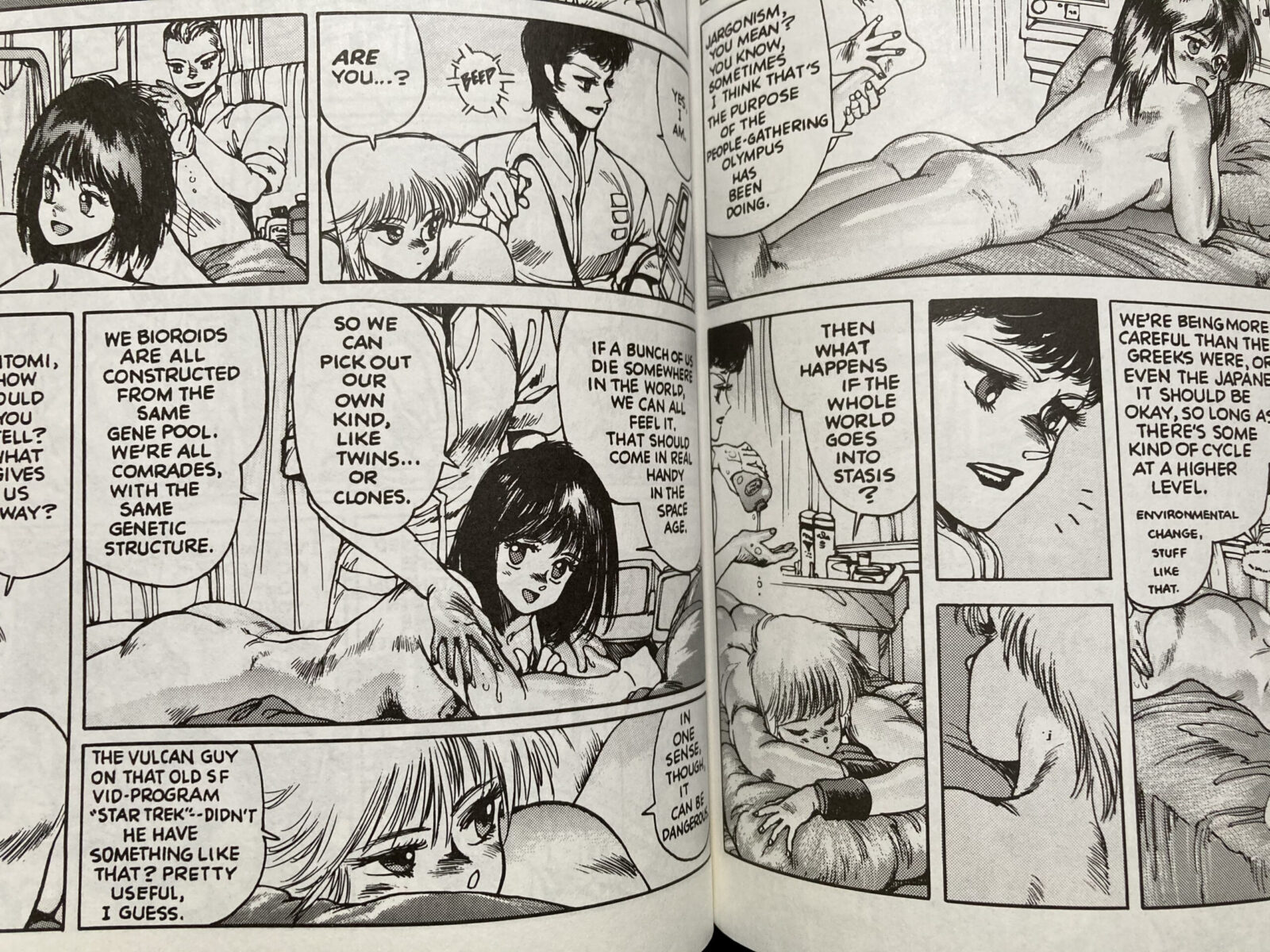

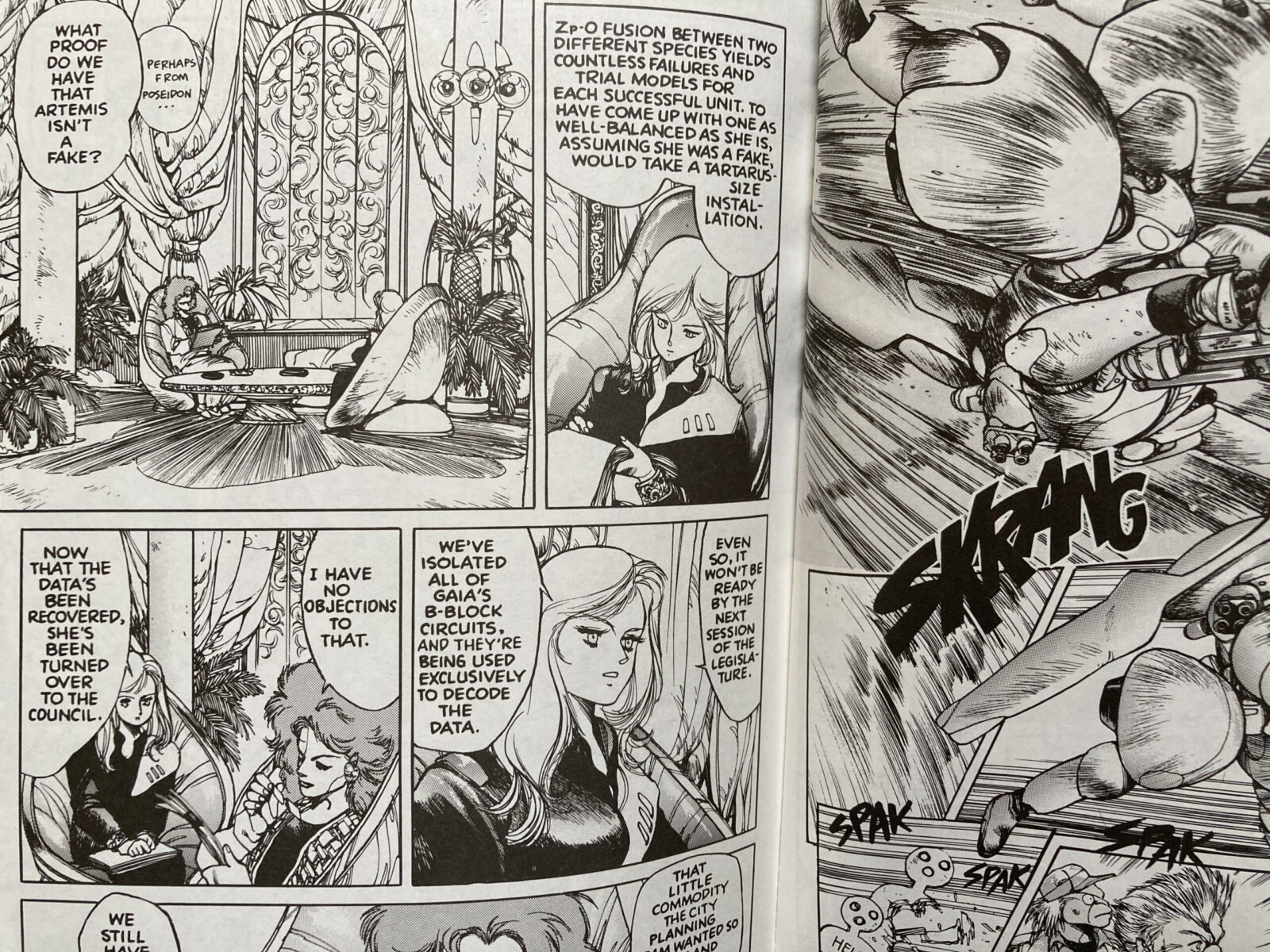

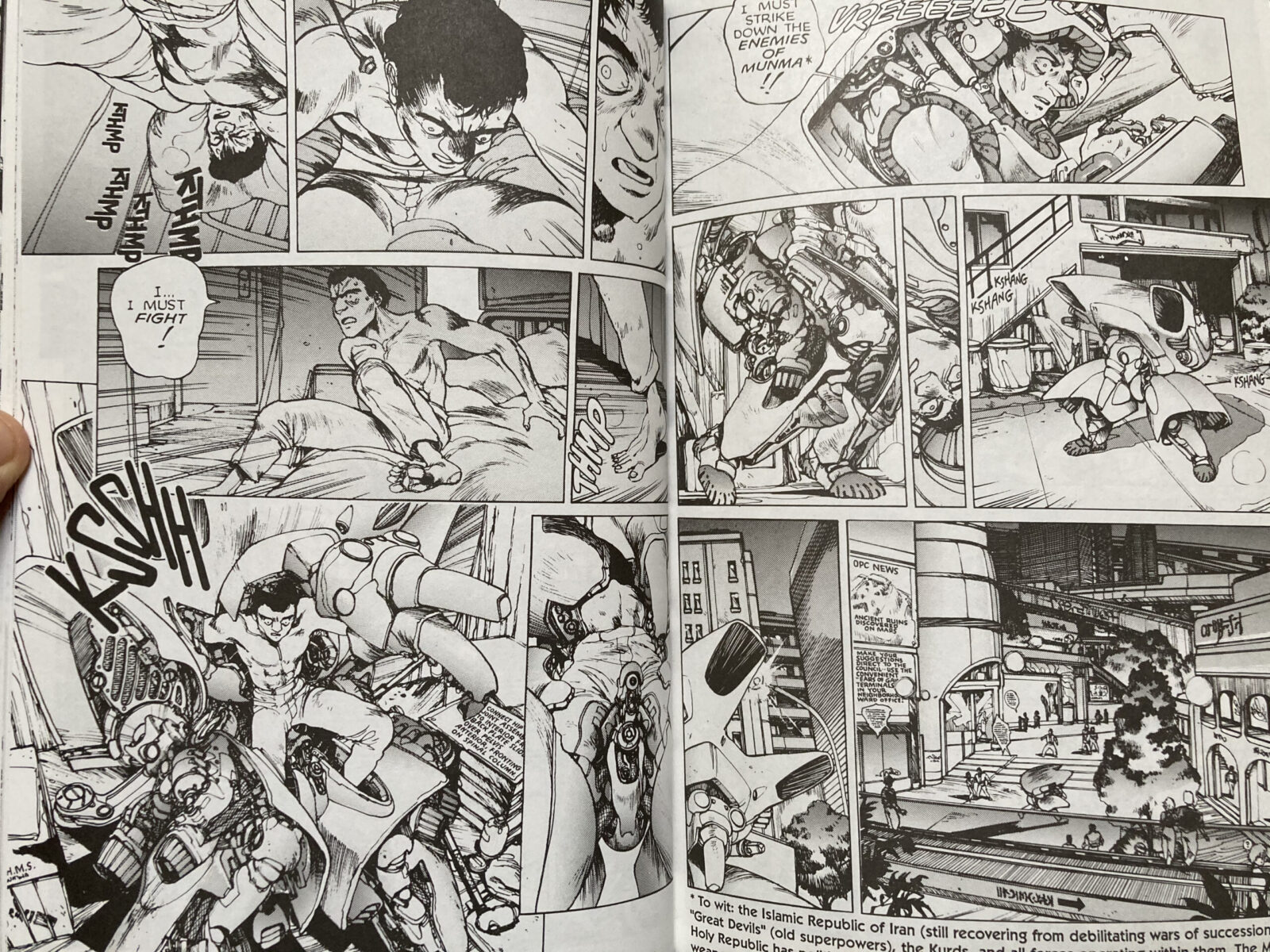

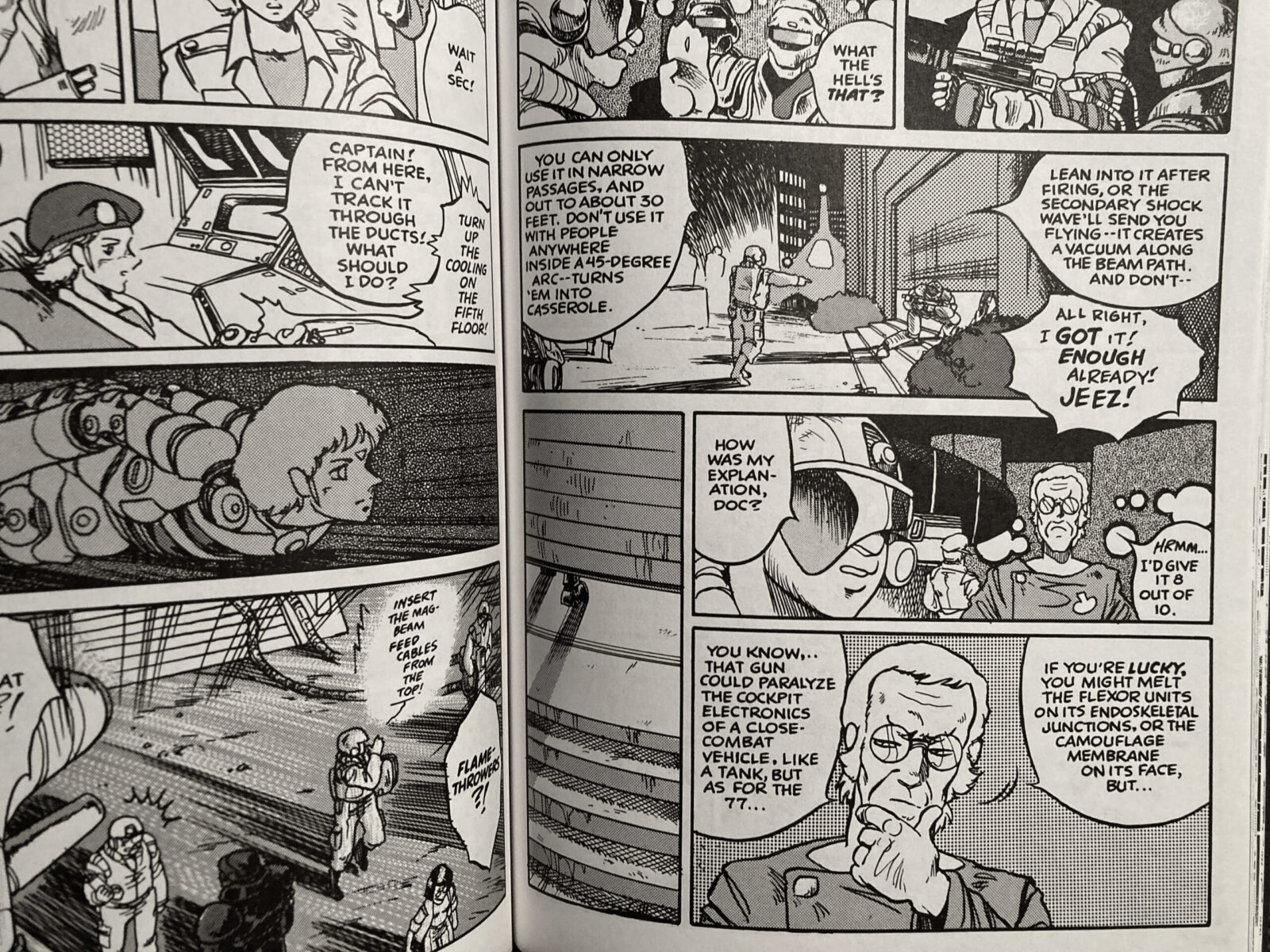

I thought I had a basic handle on the plot until it all wrapped up and I realized I’d actually had no idea what was going on. What was on the chip? What was the other information they had to decode? Why was there a double agent?... But aside from all that, this one is solid gold. It’s a huge jump in quality from the last volume (he drew the first Dominion series and I think also the Gun Dancing and Pile Up stories in the interim (see below)) and is where I feel like he solidly joins the ranks of the all-time great comics draftspeople. I was usually, while reading this, in a state of mild fogginess concerning the bigger plot picture, but was also in a constant state of rapturous wonder as I pored over every beautiful panel (just about the only thing separating this from absolute peak Shirow, for me, is a bit of clumsiness in the faces here and there). Maybe not coincidentally, this seems like where he starts really embracing his idiosyncratic interests (not that they’re the big draw for me, but rather that he just seems like he’s having fun overall; cutting loose). There’s no sex (or sexiness, imho) but there’s lots of weirdly gratuitous female nudity, with so much fleshiness and anatomical specificity painstakingly, lovingly invested in the bodies, that the characters’ more conventionally cartoony faces sometimes look like paper masks, which is very jarring. Also, Deunan (the female protagonist) has an ostentatious new outfit about every 10 pages or so, and a big full-body fashion shot to display it when each one is introduced. Is this a manga convention of some sort? If it is, I’ve never noticed it anywhere else, but here it’s really unmissably tonally strange, since most of the book is an action packed sci-fi police procedural. I can sort of see how it’s in character, if I squint, but it’s less the fact of the outfit changes that’s odd than the out-of-proportion-seeming attention he lavishes on them. It’s stuff like this that makes the cheesecakey direction his work eventually took a little less mysterious. Anyway – I’m harping on the negatives and eccentricities, but this is a really, really gorgeous book. He’s so generous with the establishing shots – and just about every background is a multi-tiered, lived-in, authentic-feeling space; there’s no cuboid white rooms with just a table in the center and a painting on the wall – everything is labored over and complicated. It really bowls me over. And it’s just in time too, since the last two volumes were trying my patience with their a-lot-less-than-perfect artwork. And also, my theory was confirmed: as long as the artwork is as beautiful as this, the headachy plots don’t bother me much, and the impenetrable technobabble doesn’t bother me at all.

APPLESEED BOOK 4: THE PROMETHEAN BALANCE (1989) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

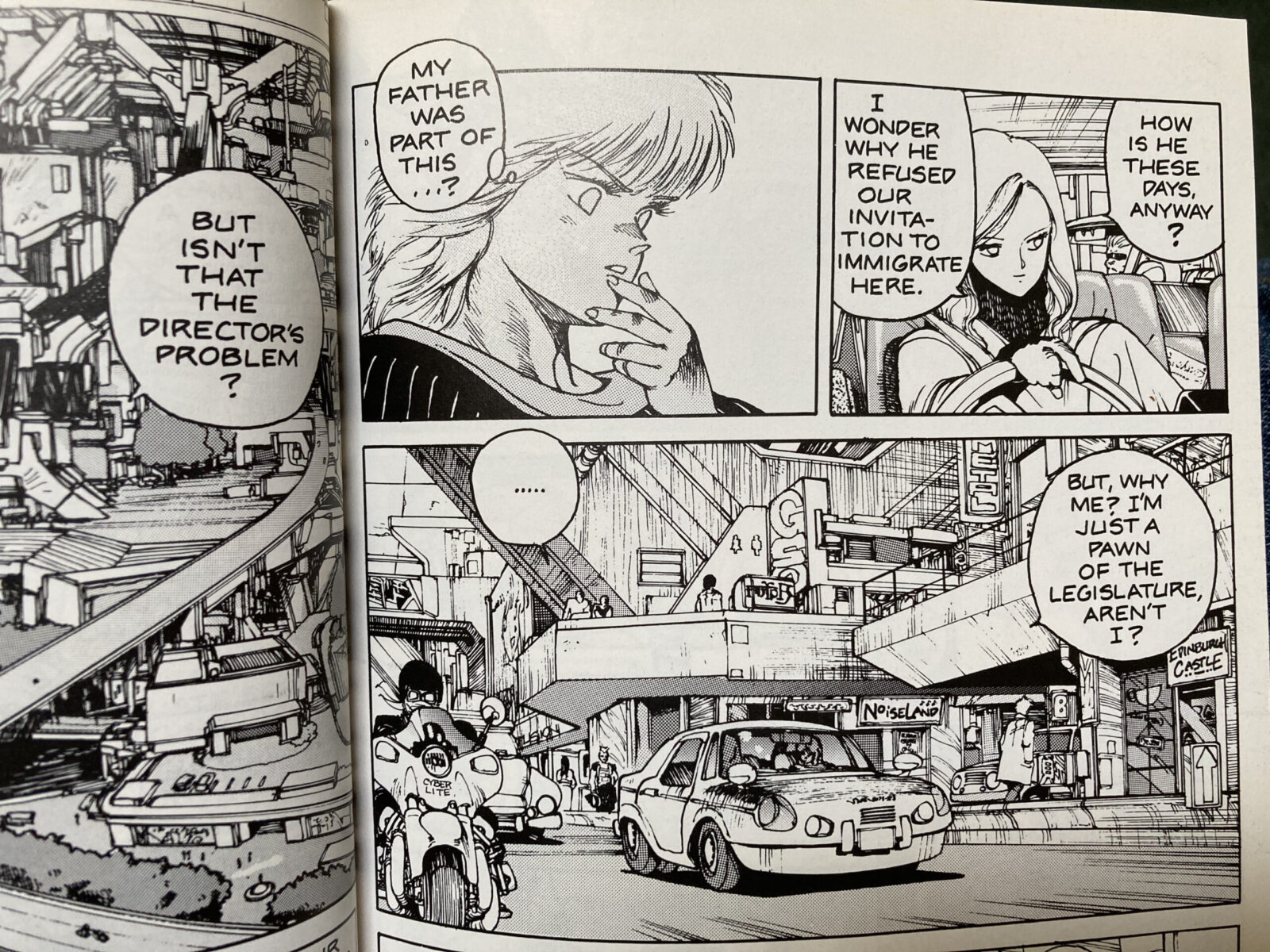

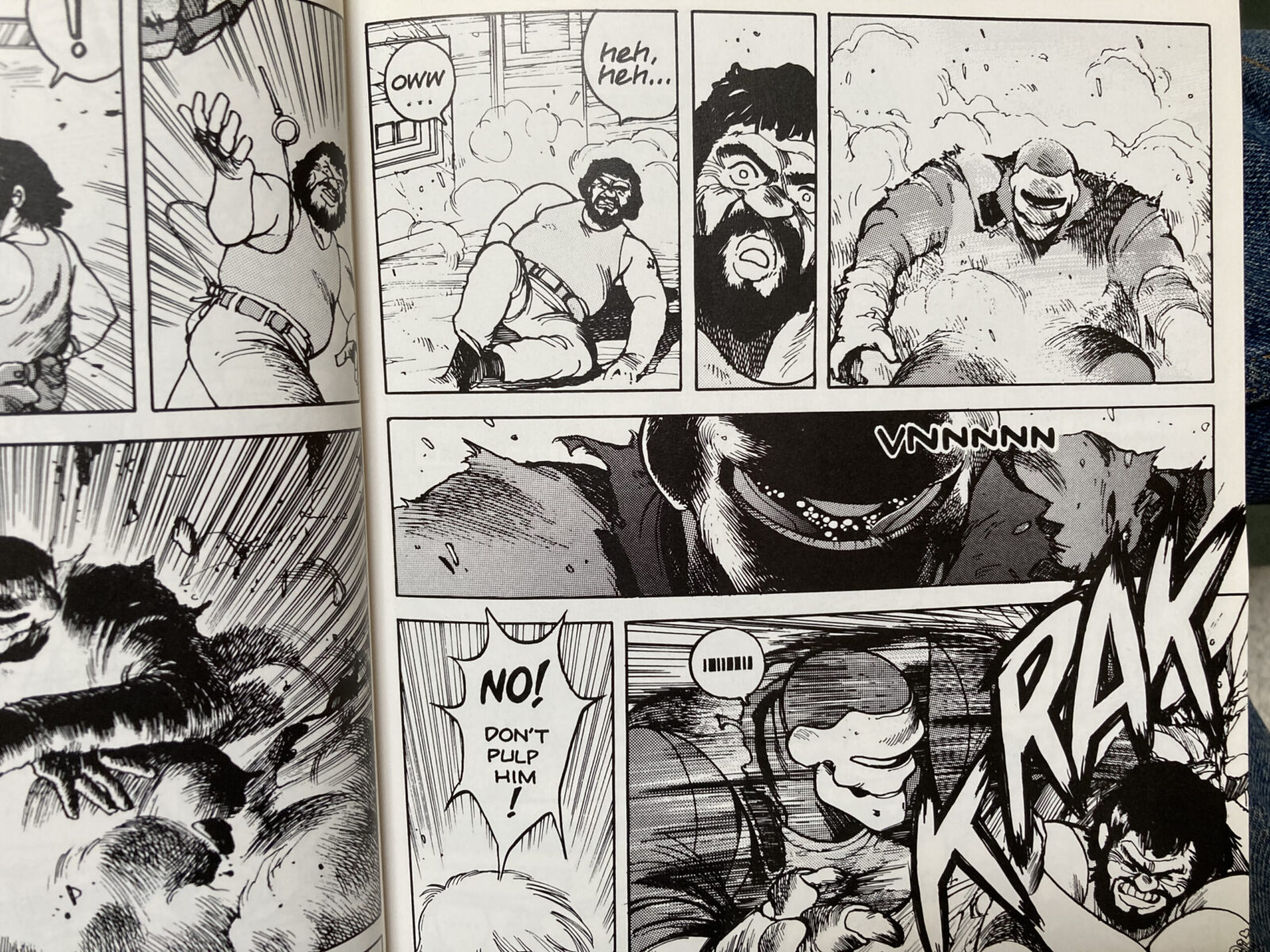

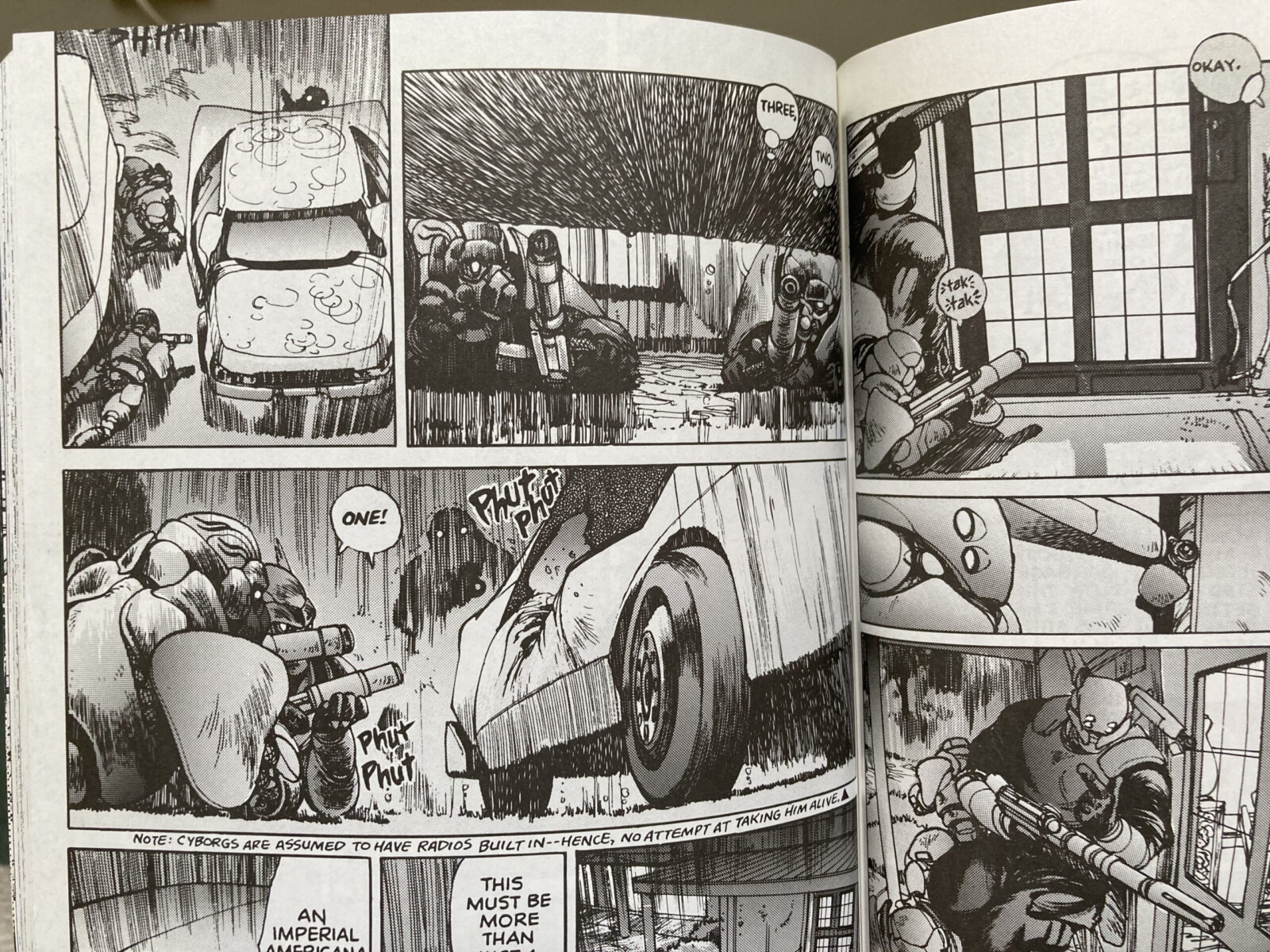

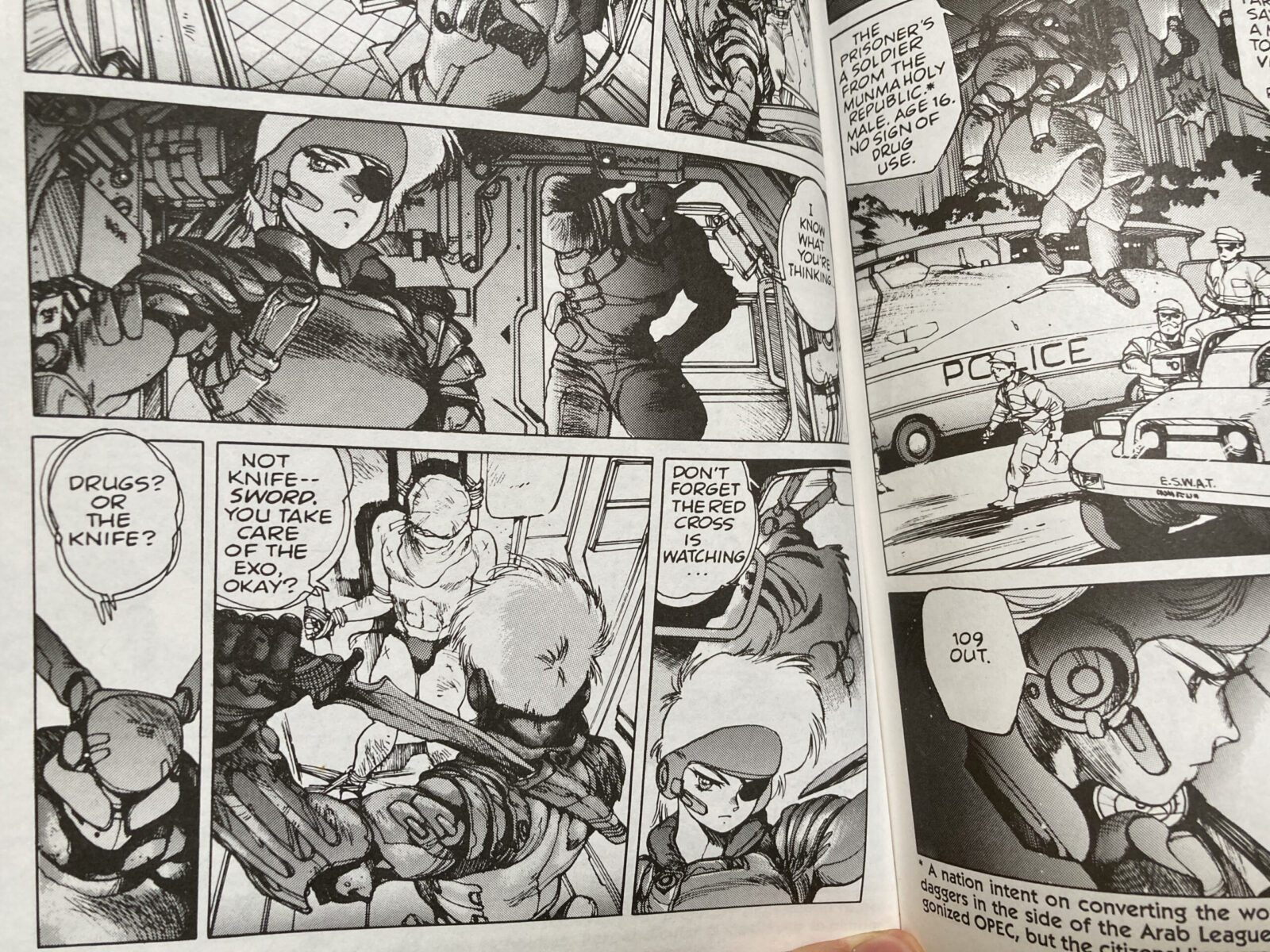

This volume’s not perfect, but big chunks of it are – maybe the whole first half. It feels like he’s firing on all cylinders, never slipping up, never unsure – holding the whole thing in his head at all times. The characters feel real and distinct and funny, like they’ve got genuine interior lives and intermingled histories, but it’s all conveyed in really economical ways that feel pleasingly terse and naturalistic. The drawings are beautiful, and the plot makes almost perfect sense. All the weirdness from the last volume is gone: there’s no ostentatious costume changes and there’s no unsettling nudity or conspicuously crotch-focused poses. Instead there’s a lot of butt-focused poses, but for whatever reason it doesn’t feel gratuitous to me – it feels like he’s found a way to successfully sublimate/integrate his lasciviousness. I dig it. It’s titillating, yet somehow respectful. Most of the butt shots occur in the midst of fight scenes that are so elegantly kinetic that they feel like a sort of fight-scene-ballet, and the beauty and strength of Deunan’s body is part of the point of it, at least on some kind of meta authorial level, if not an actual story level. No one wants to watch ballet dancers dressed in sweat pants, right? Anyway, yeah... the first half of the book was pure pleasure; not just peak Shirow, but peak entertainment generally. It snagged when I got to the scene where the bad guy explains his plans for a few pages, which just about made sense to me (but not quite), but slowed me down and took me out of the story (because I had to reread it a few times). Then just as things are picking up again, there’s two really long action sequences that are both pretty difficult to follow. Felt like volume one all over again. One was Deunan having a knife fight with a bunch of bad guys, which devolved into mostly just a mind-numbing whirlwind of speed lines, and the other was Briareos (Deunan’s cyborg boyfriend) and a few other mechs fighting a big cyborg at night, which mostly felt like lots and lots of random explosions mixed with lots of drawings of indistinct cyborg body parts. I think the problem is that Shirow treats the reader like we know the bodies of all his different cyborgs as well as we know a human body. If I see a panel that’s just a drawing of a human elbow, I can probably tell pretty quickly whose elbow it is and what they’re doing with it, but when it’s a cyborg elbow I have a hard time telling it apart from a cyborg torso or finger-joint, and I don’t know whose it is or what they’re doing. If I study it long enough, I can maybe find a foot or an eye -- some kind of recognizable landmark -- and get more or less oriented, but it’s slow going and not much fun. Side-note: the cover to this one seems to have been drawn much later, around the time he was working on Book 5. This Book 5-era Deunan has a very “modern Shirow” look to her: big doe eyes and a longer face, less-fluffy hair, and a stretched-out Barbie-doll body. It basically doesn’t look anything like the Deunan of Books 1 through 4. And also, the goofy-looking bullet casings feel like part of a more rote, tasteless, “more is more” design sense, which is how I think of modern Shirow.

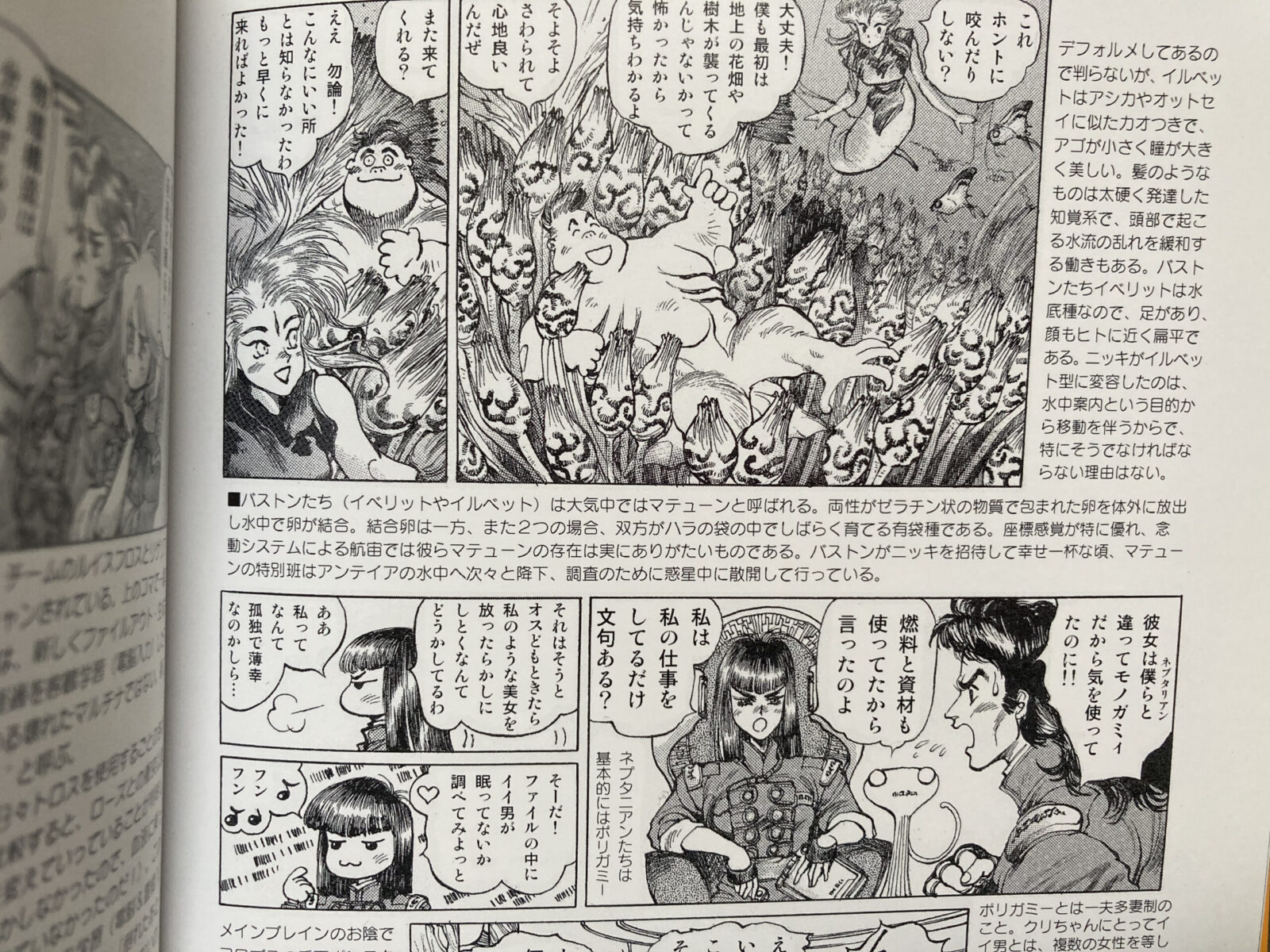

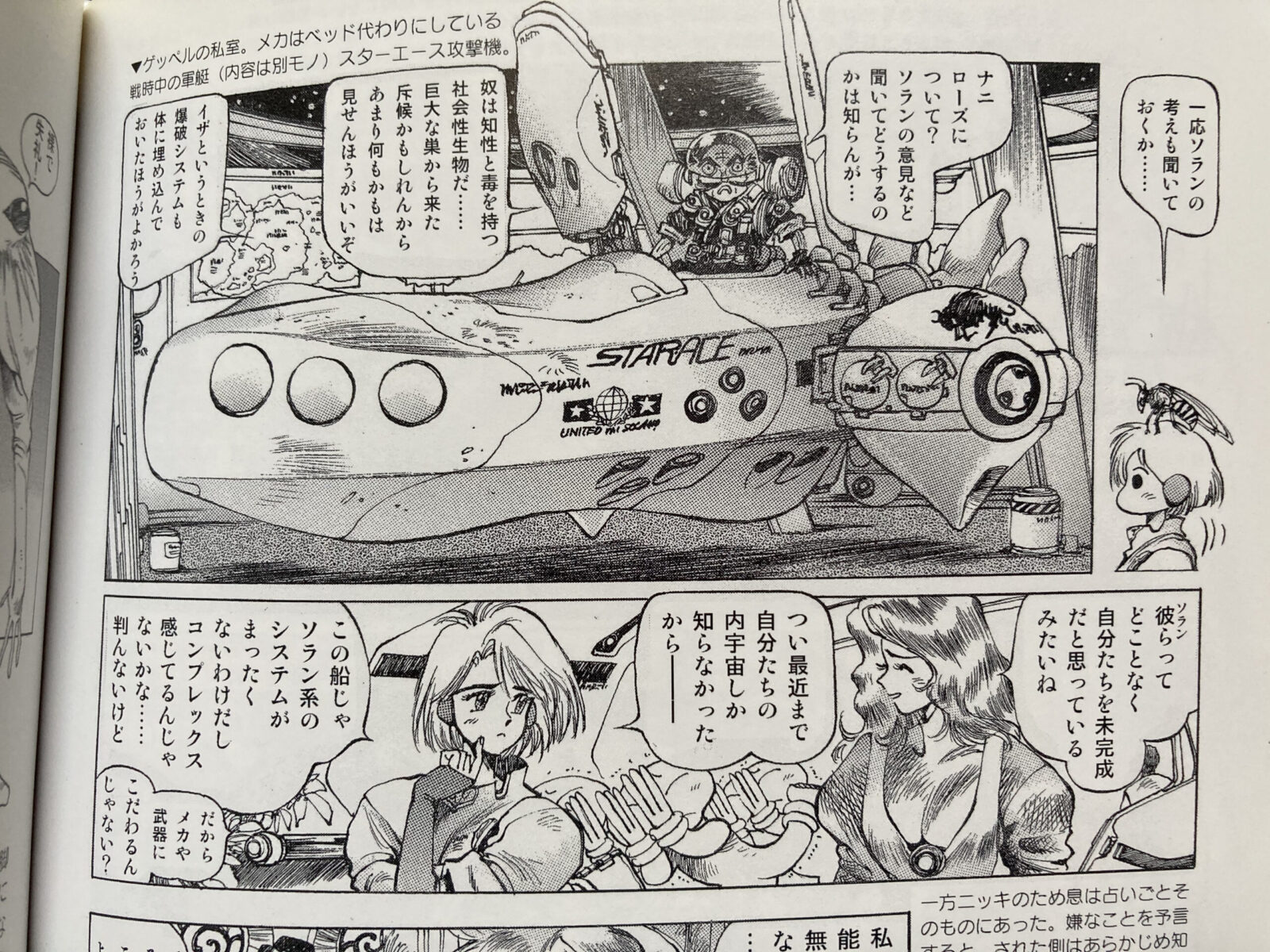

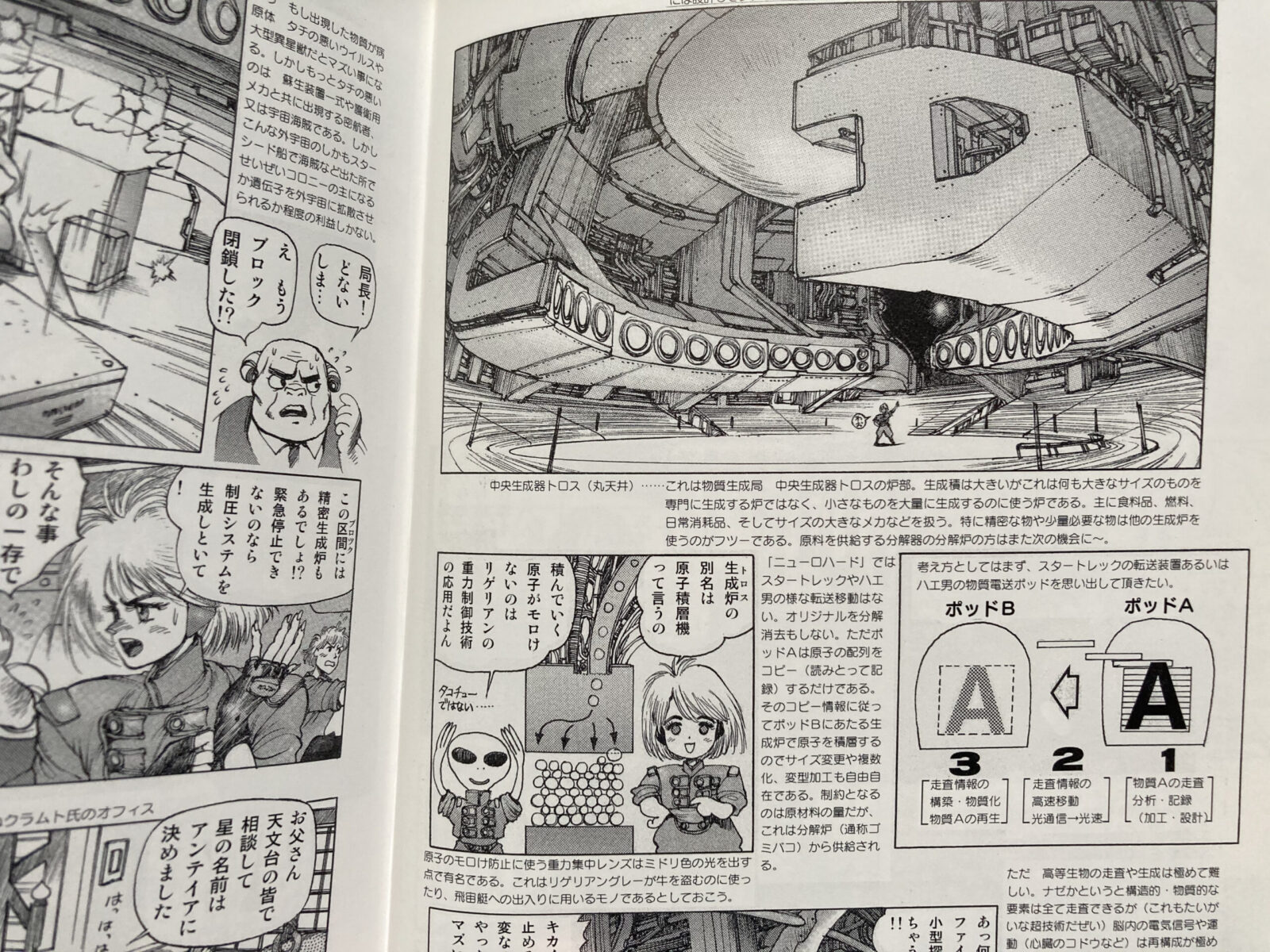

NEURO HARD (1992-94)

Every so often I have a dream where I’ll be in a bookstore or thrift store or someplace like that, and stumble onto a trove of old books that I never knew about by a bunch of my favorite artists, and I’ll flip through their pages awestruck, while greedily making as big a stack of books to buy as I can – and then I’ll wake up with lingering dream-memories of Richard Corben’s book of sea monster watercolors, or whatever strange, nonexistent thing it was. This book, Neuro Hard, which I love, feels like something out of one of those dreams: it’s an unfinished, untranslated Shirow book, that’s not really a comic, more like a heavily illustrated story outline, about a Star Trek-esque group of space explorers discovering a mysterious planet inhabited by big green bees. I can’t read it, and, as mentioned, he abandoned the project before completing it, but it’s a strange and beautiful little artifact – and the practical inaccessibility of it only adds to the intrigue (and also probably has the added benefit of neutralizing what I assume is the more headachey textual inaccessibility of the story itself). I had way more fun poring over this thing for hours than I did forcing myself to get through the first two Appleseed volumes. The artwork, as with his other late period works, is more feathery and delicate, less inky and calligraphic. Appleseed Book 5, GitS 1.5 and Dominion: Conflict all lean in this direction to varying degrees. I personally prefer the earlier, inkier stuff -- the Appleseed 3, 4, Orion and GitS 1 era -- but I feel comfortable calling it a mostly lateral move. There’s so much care going into it that the later stuff can still thoroughly charm and captivate me, especially when I haven’t read any of the really prime earlier stuff lately. It’s only when I go back and look that I remember what I’m missing. Side-note: this collection also, unfortunately, includes about 25 “bonus” pages of Shirow’s modern-period digital cheesecake stuff, which I deeply dislike and would’ve paid extra to have not be in there.

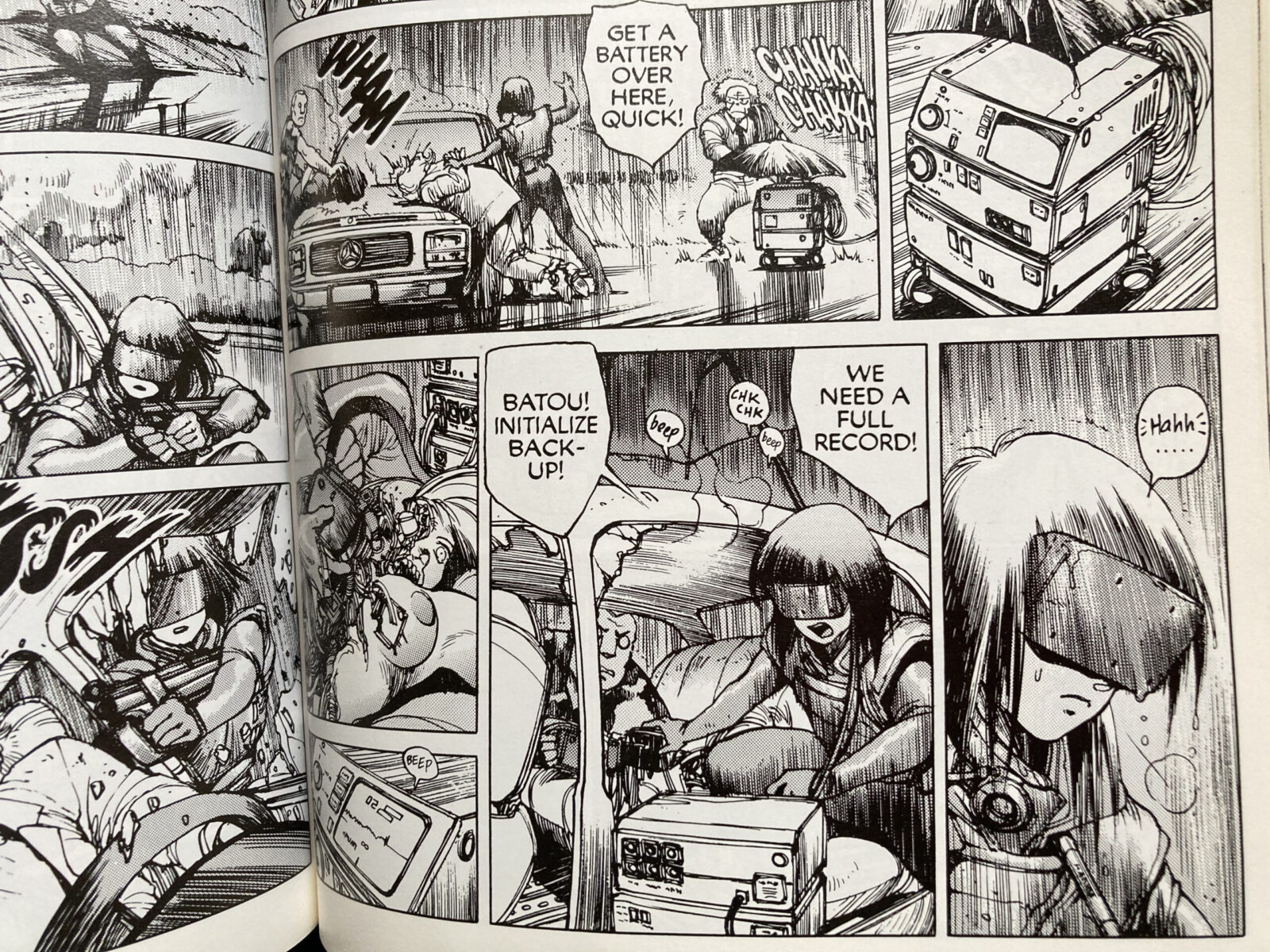

APPLESEED DATABOOK (1990) - translated Frederik L. Schodt, Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

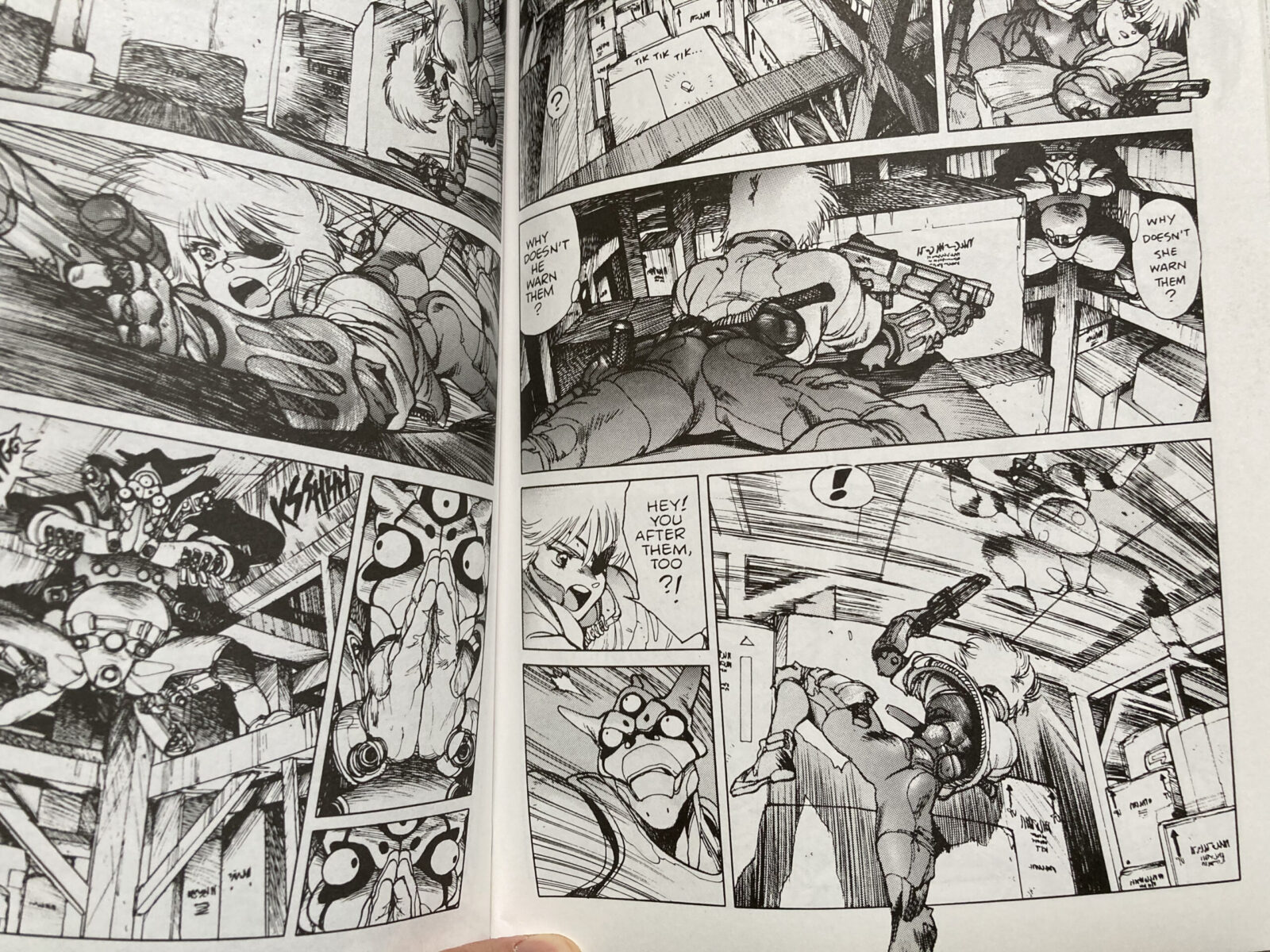

Most of this is maps and chronologies and commentaries and that sort of thing, which are mildly interesting, but the big draw is the “Called Game” short story, which takes place right after Book 4. The art is especially good (the opening shots of the diagonally oriented train station I find especially thrilling, plus he’s got Deunan and Briareos both wearing really nicely drawn leather jackets throughout the whole story, and also it’s really nicely printed, which, though I don’t have any way to do a direct side by side comparison, I suspect enhances my enjoyment a fair bit), and the tone is a little jokier than usual (and the jokes are a little funnier). Also, the story is relatively straightforward for Shirow; it’s still really dense, but there’s no one scheming to frame group A to make it look like group A is framing group B, or that sort of thing. Actually, in the story, Deunan and Briareos keep making fun of the bad guys they’re tailing for being so amateurish, so maybe that’s got something to do with it. At any rate, it was a relief. Also, side note: if you made Deunan’s hair black, redrew Briareos as Batou and Lance as Aramaki, you could pretty much slot this in as a GitS chapter, which makes sense since I think he drew GitS next. I know there’s a quote, which I can’t find now, where Shirow mentions that GitS started out as a story idea for one of his other series, but I’m pretty sure it was Dominion, not Appleseed. There’s a lot of overlap between all three, but it feels like Appleseed was evolving in a consistent direction through Book 1 to Book 4, then finally hit a tipping point and jumped the tracks and became GitS, and “Called Game” feels like the missing link that is both Appleseed and GitS simultaneously. Though I haven’t read GitS in at least 10 years, so maybe I’m off base.

DOMINION (1985-86) - translated by Dana Lewis, Frederik L. Schodt & Toren Smith

I’m glad that this was the last of the older stuff I had on deck. It was fun, but not something I’d ever read a second time. A lot of the art feels kinda heavy-handed and sloppy (better than Appleseed 2, but nowhere near as good as Appleseed 3), though a lot of it looks really good too, especially the scenes of tanks zipping around. His gift for depicting cars in motion feels just about fully formed at this point. It’s maybe even a bit clearer here than in his peak period stuff, which gets a little too ambitious sometimes, with individual panels often having confusingly incompatible-seeming areas of stillness and speed lines. Story-wise this one is very clear too – by far the most accessible of any of the books I’ve read so far. In the end though, it mostly feels like a rough first draft for the later Dominion: Conflict series, which I liked better in just about every way, and happens to not require any familiarity with this first volume in order to read it. If anything, you actually might be better off NOT having read this one, since Conflict is so thoroughly revamped/reimagined that the two seem to contradict each other in a handful of ways.

DOMINION: PHANTOM OF THE AUDIENCE (1988) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

Oops – one more old one. A short one. This was really good though. It’s the same characters as Dominion, but way more zany and goofy. Somewhere between a Mad Magazine movie parody and a Looney Tunes short. Most of the gags are really fun, and just about every panel has something comedically interesting going on. I like the meathead cop who’s painstakingly hunt/peck typing his report throughout the whole story because he doesn’t know what a delete button is and thinks he has to start over if he messes up. The look is especially loose and inky – in a way that makes sense in the context of Shirow’s later work, but was maybe a bit unprecedented at the time since, in an interview that he did with his long-time English translator, the translator asks if this story was partially inked by someone else, because it looks so different from the preceding series (to which Shirow replies that he was “just in a peculiar mental state at the time...”) The first Dominion book doesn’t cross the threshold of “would I recommend this to someone?” (or alternately, “would I ever read this again?”) but this one does (and the following one definitely does).

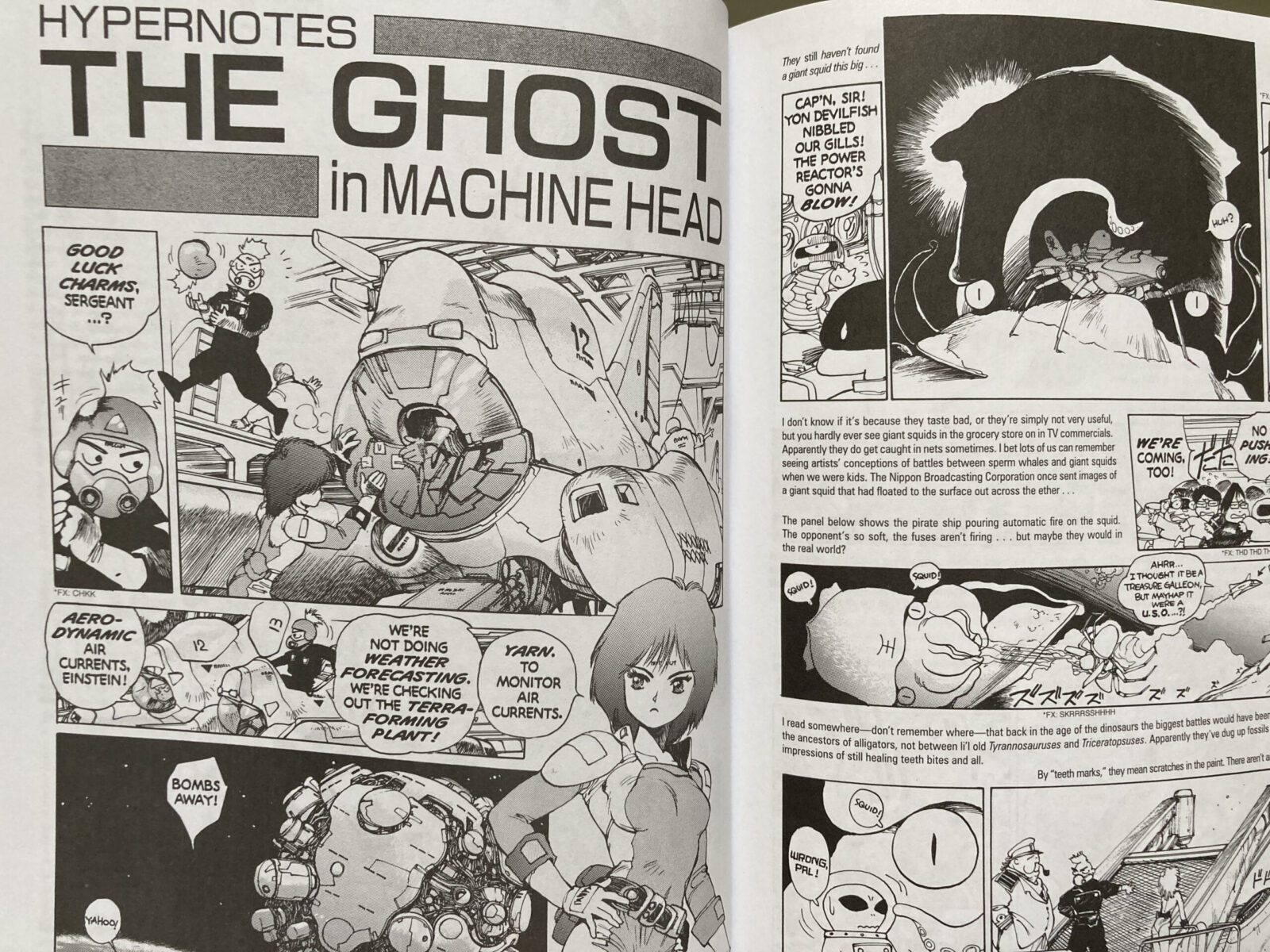

APPLESEED HYPERNOTES (1996) - translated by Dana Lewis & Toren Smith

This contains the unfinished (and apparently never going to be finished) Appleseed Book 5 (80+ pages worth) and some other odds and ends. When I first got it in the mail I hadn’t yet gotten to the Appleseed portion of my project, and flipping through it I thought it looked gorgeous. But when I finally started reading it after finishing Book 4 and the Databook, I had to put it down because I was so turned off. Mostly it’s the way Deunan is drawn: along the lines of my complaints about the Book 4 cover, she looks unpleasantly doll-like; her eyes are huge, her poses feel stiff, and her body has very un-Deunan-like, stretched-out, Barbie-esque proportions. Hitomi, Yoshi and Artemis (the other major characters who’ve appeared in previous books) get the same treatment, though they don’t show up for very long, and some of the side characters look kind of emotionally flat and stiff as well. A lot of it looks great though – the trio of villains are especially cool looking, and the story is pretty interesting. It’s extremely high level work, but my feeling that, with this volume, Shirow had grown slightly less engaged and passionate about comics-making, put me in a kind of existential cold sweat. I don’t like it when artists “decline” – it makes me fear for my own talent and passion. Conversely, I love when artists thrive in their old age (like, for example, Richard Corben or Cormac McCarthy), it’s very heartening. Anyway, I eventually had to embark on a little mental adventure to convince myself that maybe Shirow is happier with his new style and subject matter, and that that’s what’s really important, and so what do I have to be afraid of? Which worked pretty well, but suffice it to say that reading this volume was more fraught and complicated than any of the others.

Visually, it looks a lot like Neuro Hard: feathery and busy, with a more delicate, airy line than his mid career stuff – which adds to the general confusion because I think Neuro Hard looks perfect but Appleseed 5 looks not great. Maybe the bottom line is that Book 4 and “Called Game” are impossibly tough acts to follow. On the nitpick side of things: this one is not only printed in an especially dull, almost grayish matte ink, but is also shrunken annoyingly small. Dark Horse’s last reissue of all their Shirow stuff was in this tiny size (not sure about the printing process in the other volumes though). Luckily I managed to track down just about everything else in an older, larger format (Hypernotes and Neuro Hard only exist in tiny form, as far as I know). I guess purists might prefer the newer ones since they’re “unflipped” from the Japanese right-to-left format – and actually I do usually lean towards that sort of purism myself, but not with Shirow for whatever reason. Maybe it’s because my first, formative exposure was to a “flipped” GitS. If I look at one of my own drawings flipped, it makes me wanna barf, but I’ve seen lots of Shirow’s work in both formats and honestly it looks exactly the same to me either way. So... if Dark Horse is listening: my annoyances ranked are #1– shrunken size, #2– matte printing, and flipped vs. unflipped doesn’t matter.

The other noteworthy inclusion here is a 12-page story called “The Ghost in Machine Head”, which I really enjoyed. Structurally, it’s very similar to Neuro Hard (at least, as far as I can tell without actually being able to read much of Neuro Hard): they’re not quite conventional stories – more like a linear series of scenes and tableaus mixed together with authorial digressions and character designs and that sort of thing. I really like it – it feels relaxed and intimate. I wish he’d done more stuff like this – it feels like he was on the verge of inventing a new storytelling form to fit his evolving interests and sensibilities. Also of slight historical interest: in one of the footnotes to the Book 5 section he mentions a planned sequel to Orion which I’ve never seen mentioned anywhere else, so I guess that can get added to the list of abandoned Shirow projects.

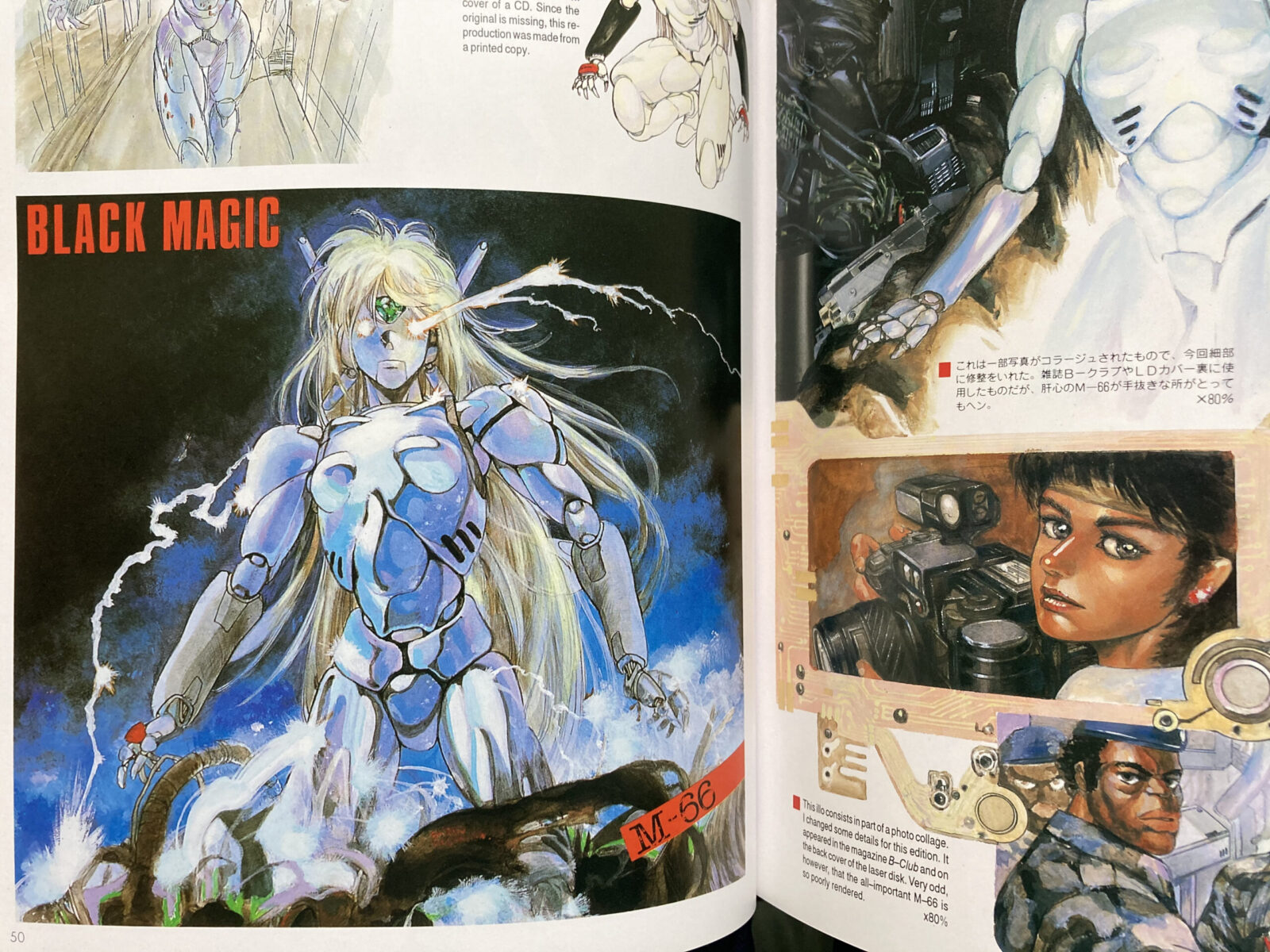

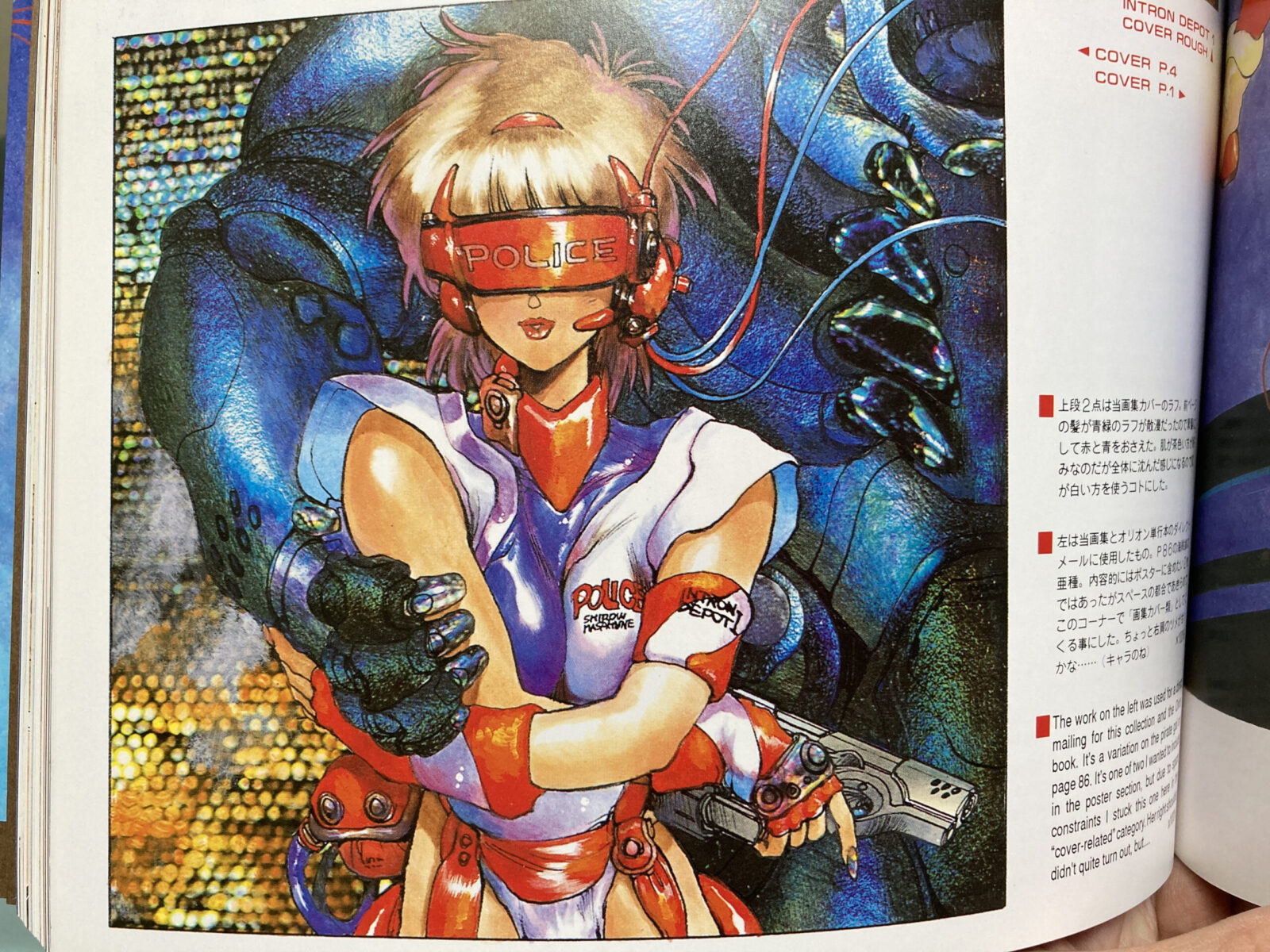

INTRON DEPOT 1 (1992) - translated by Toren Smith, Alan Gleason, Dana Lewis & Frederik L. Schodt

Shirow’s got a lot of art books, but this is the first, and the only one, as far as I know, that isn’t primarily digital art (I think this one is entirely analog, though I’m not 100% sure how he got a few of the color effects – if they were computer assisted or color-photocopier assisted (which I suppose should count as digital, but I consider analog)). It’s beautiful and informative, and very nicely made. The work is pretty samey throughout though -- lots and lots of pretty-girls-piloting-mech-suits -- but, as Shirow apologetically acknowledges in his commentary, that’s just due to the type of work he was doing at the time, not any kind of curatorial decision. The nicest, most visually varied stuff is the little reproductions of the GitS color pages, but it’s hard to picture anyone who owns this not also owning GitS. On balance, though, this was just what I wanted it to be: almost all of the painted work he’s ever published, plus lots of interesting contextual factoids (for such a private guy, he’s very frank and un-precious when talking about his work) and some welcome surprises, particularly the inclusion of the intended cover for Appleseed Book 5.

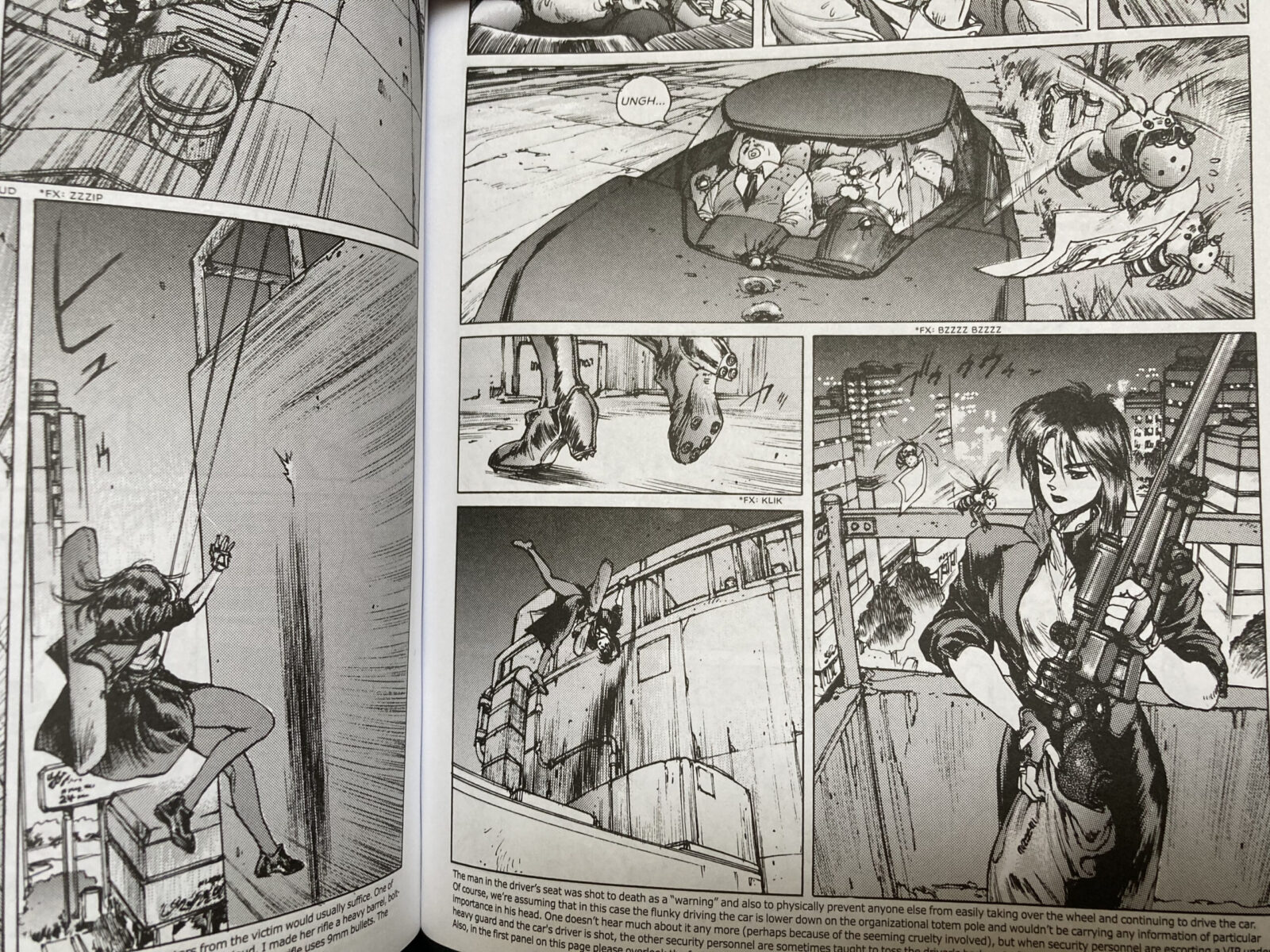

GHOST IN THE SHELL (1989-90) - translated by Frederik L. Schodt & Toren Smith

Surprisingly (since my childhood memories of it are so fond) this was a big struggle. Right off the bat it’s very confusing story-wise (as usual the big picture is mostly pretty clear, but the dialogue can be impossible to follow; this was the first one where I started to wonder if maybe Shirow’s long-time English translator maybe wasn’t such great shakes), and the cyberpunky hacker jargon peppered throughout the whole book is so on the nose that, in 2021, it feels more like parody than primary source. Plus, as mentioned, I went in with sky high expectations, which is always a killer. It feels like he was going for a more flamboyant, action-movie feel with this one, versus the relatively less flashy (though still action-packed) Appleseed stuff, but then at the same time the characters in GitS get pretty much zero conventional characterization – no backstories, nor much in the way of fears or desires or anything like that, and the text is even more fragmentary and dense than usual, so there’s a weird tension to the whole thing, like it’s pushing towards both more and less mass-appeal at the same time. On top of which, the book is constantly jumping back and forth between gritty and goofy tones and drawing styles. The overall effect is a sort of kaleidoscopic slipperiness, such that I was having a hard time finding a stable point of view from which to experience and form opinions about the story. But then, about 2/3 of the way through, out of exhaustion, I tried a different approach: I started consciously reading it as though it were Neuro Hard (his book which I’d read a couple months earlier, and loved despite it being in Japanese and too elliptic and weird to parse by pictures alone). I told myself that I wasn’t going to understand it (GitS), that I was just peering into an alien world and taking from it what I could. After which I was a lot more relaxed, and things actually got easier to understand since I was able to let any impossibly inscrutable little details just pass peacefully through my net. Also, I suspect the book just gets easier to read as Shirow imperceptibly settles into more of a groove as he goes along. So he and I both settled into our new grooves and the experience was much improved. Though it was still not exactly a page-turner; still something I had to spend mental calories “translating” in real time.

GUN DANCING (1986) and PILE UP (1987)

Not too much to say about these, since they’re both in Japanese. I’ve used Google Docs to auto-translate entire French and German comic albums into English (the results are pretty good, but it’s a huge pain and takes forever (mostly because the image to text conversion function doesn’t understand word balloon positioning)), but, for whatever reason, Japanese doesn’t work nearly as well. Basically not at all.

These are both Appleseed prequels, and both are short, relatively simple-seeming police investigation stories. Gun Dancing is about Briareos in pre-cyborg form getting busted after carrying out some kind of illicit assassination mission (I think). And Pile Up is Deunan’s father getting entangled with a beautiful exotic dancer while investigating a murder. Gun Dancing is the earlier book, and is not too remarkable looking, but Pile Up is quite pretty. One could say it maybe looks a little bit rushed, but I found it refreshing. It’s got a light, clean feel; not as dense and dark as Appleseed proper. Pile Up is also unique in that the dancer character doesn’t have the same face that just about every other pretty female Shirow character shares. Both books also come with a cd-rom, with which you’re supposed to be able to read the comic in “e-manga” form. I think that means a sort of automated slide show, with music and sound effects, but I couldn’t get them to play, despite half an hour of tinkering.

GHOST IN THE SHELL 1.5: HUMAN-ERROR PROCESSOR (1991-96) - translated by Frederik L. Schodt

I was about to differentiate this from the original GitS by describing it as a collection of short stories, but the first book is that too. For whatever reason, when I think about the original, I think of it as “about the Puppeteer”, but the Puppeteer storyline only occupies the last two chapters out of ten. This one has no unifying threads at all. Plus, stylistically and quality-wise, it’s kind of all over the place, so you really feel the “collection of odds and ends”-ness of it.

The first story’s okay. It’s pretty and tasteful, but it’s also confusing and seems to have lost something in translation: there’s a handful of moments where characters seem to be reacting to a joke or provocation and I can’t figure out what it is they’re responding to. Similarly, throughout the whole thing all three of the good guys are being inexplicably, unprecedentedly mean towards the “damsel in distress” character (who’s come to their agency for help when she suspects her father has technically died but is nonetheless being remotely controlled by brain/body hackers). There’s usually a fog of confusion overlaying my Shirow reading experiences, but this story’s fog felt somehow less organic. More like somebody was in a hurry and screwed something up... Shirow or the translator – I don’t know. Too foggy to tell. On the plus side, there’s a more uniformly serious tone to this story, which was a relief after the tonal static of GitS 1. The downside to that upside is that, without his impish depiction or comedy-relief moments, Chief Aramaki turns from an intriguing character to a generic one.

The second story is great though. It’s as interesting and entertaining as anything in the first book – maybe more so. Actually, plot wise, it’s a bit similar to my favorite story from the original - in which Kusanagi and Togusa get cornered in a factory and have to fend off a near-invincible robot tank (this time they’re in a hospital). There’s a few conveniently cut corners in the story (like why is the brain-hacked hostage being remotely controlled to operate the assault tank? Shirow acknowledges that there doesn’t really need to be anyone piloting it at all, but doesn’t address why, on top of that, it’s the high-value hostage, of all people...), but it’s small potatoes compared to all the fun stuff.

Things get wobbly with the third story: I got snagged early on by what I think is a mistranslation, where they’re talking about murder victims A and B, but then some of the chronological identifiers seem to shift from one to the other. It’s kind of a small thing, but when I’m reading something that requires so much effort to parse, and so much faith to believe that it’s parsable at all, it’s pretty bothersome. Worse though is that Shirow’s artwork here is looking sort of unpleasant. Strange eccentricities that were hinted at in the first two stories start becoming prominent, like the really dark noses and the futuristic crow’s feet on everyone’s eyes (which migrated to Batou’s arm by the time the cover got drawn). Characters’ heads start to have a sort of chunky, Easter Island thing happening, and the inking gets thick and scuzzy. I don’t believe it’s actually true, but it almost looks like he was taking inspiration from contemporary American mainstream comics and cartoonists of the time, like Joe Madureira, or Trent Kaniuga’s Creed, if anyone remembers that.

The fourth story gets overwhelmed by these yucky-looking mannerisms, and I was borderline skimming by the time I finished it. Easily my least favorite unit of story from this whole Shirow-reading project thus far, which took me by surprise, since I’d already flipped through GitS 2 a bunch and, at least in the black and white parts, that book looks very well drawn – kind of Neuro Hard-adjacent for the most part. Is it possible that this story was drawn after GitS 2? I’m looking at the detailed chronology on shirowledge.com and it doesn’t seem like it. I guess he was just trying something new.

GHOST IN THE SHELL 2: MAN-MACHINE INTERFACE (1997) - translated by Frederik L. Schodt & Toren Smith

For years I’d been under the impression that this book is just a total piece of junk, and though a lot of aspects of it are kinda junky, it turned out to be a real-deal, serious piece of work. Definitely one of a kind. Even just taken purely as an imagining of a near-future milieu, it’s pretty interesting and unique: the main character, Motoko Aramaki (I just finished the book a few minutes before writing this and am embarrassed to admit that, while I’m pretty sure Motoko Aramaki is in some sense the same consciousness as Motoko Kusanagi, the main character of GitS 1, I don’t know what that sense is...) flits between digital and earthly terrain so quickly and seamlessly that there’s barely any distinction between the two; and while on earth she flits instantaneously between at least a half dozen or so bodies she has stashed around the globe, rendering physical distance mostly just a minor annoyance to be factored into her strategic calculations, like lag time in a digital connection. Combined with the incessantly complex dialogue, the cumulative effect is of a future world operating at a higher tier of mental pace than ours, which is not something I can remember encountering in other sci-fi. Granted, Motoko is (I think) part AI, and the average future-person on the street isn’t living the kind of life she is, but still.

The story has a noir-style structure, where Motoko is the lone-wolf detective chasing down a mysterious criminal through all kinds of hard-to-understand twists and turns. When she finally finds the culprit, things get very metaphysical (this volume, unlike GitS 1, mixes in a lot of ESP and “psychic channeling” stuff), and that’s when I got totally lost, not too surprisingly. I could sort of intuitively grasp that something satisfying was taking place though, which wasn’t the case when volume 1 blossomed into the metaphysical.

Like the first volume, there’s an odd tonal tension in this book, wherein the technological/operational verisimilitude is super cranked-up (big chunks of the book are just Motoko barking opaque, antivirus-themed jargon at her AI assistants as they invisibly battle digital opponents (I like this kind of stubbornly thorough stuff, but your mileage may vary)), but also, on the other hand, the incongruous, soft-core porniness of the outfits and poses is cranked up to really glaring levels. I almost wonder if he was trying to balance the very-hard-to-parse story with some seductive, “fun” elements... but if I had to guess, I’d say he just really enjoys both and writes the kinds of books he’d want to read.

The biggest problem with the book by far is Shirow’s infamous digital artwork, which is a real drag to look at and takes up about two-thirds of the page count. He apparently builds digital 3D sets, then rotates them around, finds a good composition, and draws the characters in. Aside from looking lazy and boring, it’s also much harder to visually “read”, since there’s no artist-imposed hierarchy of information – it’s all just uniformly barfed into the panel and you have to try to figure out on your own which objects and areas are important. And it’s not just the backgrounds: the characters end up looking worse too. It’s a similar sort of problem, where, when he’s drawing in ink, there’s a hierarchy of information: there’s areas of negative space, there’s thick lines and thin, there’s hatching that elegantly indicates force and speed and volume - but in the digitally painted characters, there’s an inert, airbrushed uniformity to every body part and every piece of clothing. Plus, it’s in these digital sections that he gets most carried away with the fleshy female bodies and panty shots. Weirdly, some of the black and white sections are about as gorgeous as anything he’s ever done, but then there’s also a black and white section that looks like it has Google Sketchup screenshots for backgrounds, and then a handful of sections that are conspicuously washed out, as though the raw scans didn’t get the proper pre-press adjustments. It’s all over the place. I suppose that’s the big takeaway: this book is a mess – but an unusually smart, serious mess. Really, the artwork is the only thing holding it back from being on the same tier as his other major works.

Side-note: I bought the Kondansha edition first, which is regular-comic sized, but it turned out to be awful looking. It’s really dark and oversaturated, the paper is uncoated, and it appears to just be the same files as the smaller version blown up, so it’s all blurry and pixelated. The Dark Horse version is the way to go. Conversely, the Dark Horse edition of GitS 1.5 (which I bought years ago), has nice paper but is too tiny to comfortably read, so I picked up the Kodansha one for this project, which was a big improvement: good size and crisp artwork (but matte paper... so it goes).

BLACK MAGIC (1983) - translated by Alan Gleason & Toren Smith

Initially, I wasn’t going to read this one at all, since I’d only ever heard bad things about it, but now that I have (for the sake of completeness), it’s kinda nice to have read it right after GitS 2. It feels like my hero’s journey has come full circle (Black Magic is Shirow’s first published book).

Anyway – this wasn’t of much interest, other than in its relationship to the rest of Shirow’s oeuvre. It’s basically four interrelated short stories that don’t actually have much to do with each other. They kinda tell the story of the downfall of the ancient Venusians and the genesis of human life on Earth, but in such an abbreviated, indirect way that you definitely wouldn’t say that that’s what this book is “about”. It feels more like a testing ground for Shirow’s visual and thematic interests, and he manages to fit in pretty much every single one – it’s got SWAT raids, hyper-competent female protagonists, feral female robot hunts, mystical techno-sorcery, mech-style armor suits, goofy comedy, tanks, space travel, AI-guided government, genetically enhanced post-humans, ironic(?) indifference/contempt for common shmoes... the only thing that’s missing is the titillation element that eventually took over.

The drawing style has a very '70s feel to it (I’m no manga expert, so that’s as specific as I can get), which looks nice, if a little “teenager-y” in execution. The spaceships and submarines look really good, and there’s a nice, painterly feel to his grey-tones. It’s got a gruff, goofy, cartoony sense of humor, and it’s all pretty straightforward and easy to understand. The problem is that it’s also really hard to care about, since there’s almost no characterization whatsoever. The “protagonist” doesn’t appear in the story all that much, and it’s not really clear what motivates her (at one point she lets a renegade robot go on a killing spree to (I think) teach humanity some kind of lesson, and then later she saves millions of humans from a spaceship crash.) The main antagonist doesn’t appear at all, except by name. There’s just not much to grab onto, emotionally. Not recommended. Though more enjoyable than I thought it would be, based on his next book, Appleseed Book 1, which is smarter and more original, but more of a confusing slog.

* * *

Annnnd.... that’s it. After 1997, Shirow started primarily publishing pornography and pin-up art. I think there may be some narrative elements to some of it, but I haven’t taken too close a look. I also am not sure if there’s a ton of actual sex depicted, but the images I’ve seen still manage to be very extreme (you can Google it for yourself...). I’m not opposed to this shift in principle, but this newer work all has the same airbrushy, 3D-background look as the worst parts of GitS 2, so it doesn’t hold much interest even just on a visual level. Plus, for my taste at least, the subject matter is so ridiculously over the top that it’s not really erotic at all, and the women are so anatomically strange (always extremely lithe and narrow-hipped, with long, rubbery legs and torsos) that they barely even read as human. Nor do the scenarios depicted evoke any sort of human reality at all... my eye just slides frictionlessly over every page, finding no purchase whatsoever. To say it all looks like a bunch of plastic is too generous; it’s more like digital plastic. And this is what he’s been doing for the last 24 years – ten years longer than his comics phase. Other than the loss of his notes and materials, I haven’t found any explanations from the man himself for the drastic change. I have run into a half-joking fan theory that Shirow himself actually died in the quake and was surreptitiously replaced by an assistant... but that theory gets a lot less compelling when you actually read through all his books; the signs of his gradually shifting interests aren’t too hard to see. And I expect a fake Shirow would be trying harder to look like the Shirow of old, rather than zooming off into the wilderness like this.

So what’s the big takeaway at the end of this read-through? Do I now feel like I know Shirow better than I know my best friend? No, not really. He’s so consistent in his interests that reading 15 of these didn’t tell me much more than reading 1 of them. I guess the takeaway is that I really revere this guy and it was a pleasure to partake in his generous, passionate craftsmanship from beginning to end (despite some bumps along the road.) As far as I can tell, he really did it all his own way – even his apparent commercial compromises are totally off the wall. He told the most dense, inaccessible stories you could imagine, and ended up outrageously popular and successful. It’s wild. It’s inspiring. He’s one of a kind, but... aren’t we all one of a kind? Shirow Masamune, if you’re somehow reading this: thank you, and congratulations! What else is there to say?