If you’re ever looking for a surprisingly complicated emotional ride, I recommend the audiobook version of Burt Reynolds’s 2015 memoir But Enough About Me. It’s an engaging enough book, but it becomes something else when you listen to it. Reynolds reads the memoir himself, in a voice that is slow, soft, and unsteady — at times, barely a rasp. It feels like it’s going to be a disaster, and you might even find yourself wondering whether he only agreed to do the recording because of his much-publicized financial troubles. So, it’s a tense listen, to say the least. Each sentence he starts sounds like it could be his last.

But slowly, that frail, hesitant creak of a voice — raw, almost helplessly honest — grows on you, revealing layers of emotion. And by the time Reynolds gets to his chapter on Dinah Shore, the massively popular singer and TV host with whom he had a very public relationship in the 1970s, he is choking back actual tears. She was 20 years his senior, a fact which made many in the press cynically question whether their romance was real. But it’s clear he loved her greatly. He sobs openly as he talks about Shore’s kindness and openness, and all the advice she gave him. It’s devastating, not the least because Burt Reynolds was once the kind of man who might have been horrified at the idea of crying in public.

There’s a ramshackle honesty to that memoir, and there was a ramshackle honesty to the man, too. As a performer, Reynolds, who died yesterday, may not have always seemed like much; he actually had quite a bit of talent, and range, but he didn’t always explore it, and he didn’t always seem to be trying all that hard. But something honest always came through, like he’d let all of us in on a secret.

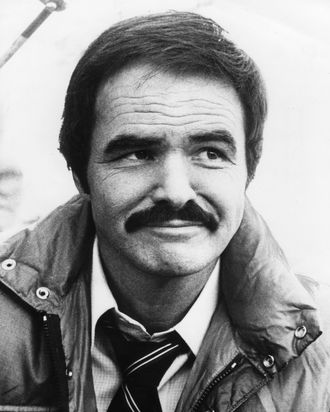

Maybe it’s because he had never planned to be an actor. A sophomore year football injury at Florida State, followed by a near-fatal accident in which he drove headlong into a flatbed truck loaded with concrete, had spelled the end of a promising sports career. He chanced into acting while studying to become a parole officer and fell in love with it, but he was still shy, and quiet, and not entirely aware of his talents. He was handsome and strapping, to be sure, and in his early years he bore an uncanny resemblance to Marlon Brando, so much so that strangers would follow him on the street. (This annoyed him so much that it was one of the original reasons he grew the mustache — though, interestingly, when Brando had a mustache he never looked like Burt Reynolds.) But he was kind of the anti-Brando as a performer: He didn’t try to show you the effort. He dropped out of the Actor’s Studio after just a few sessions. In his early years, he still had difficulty making eye contact: He once failed to realize Greta Garbo was hitting on him.

But he did have something else. His acting classmates and teachers were reportedly quite taken with the way he laughed, and wondered how he could turn it on so easily. He replied that his problem was he didn’t know how to turn it off. In a 1961 production of a play called Look, We’ve Come Through, he froze up on stage, forgot his lines, and couldn’t stop laughing. Afterward, everyone from Tennessee Williams to William Inge came to his dressing room, showered praises on him, and promised to write plays for him. (None of them did, of course, and Reynolds left for Hollywood soon after.)

Like almost all movie stars, Reynolds managed to turn what might have been drawbacks into strengths. Though we might now think of his persona as one of confident machismo, it’s possible he never entirely got over that initial reticence. But maybe that’s why he seemed so confident. At times, he seems to hover over the movies he stars in, almost as if he’s refusing to engage with the material. You might mistake him for someone who doesn’t care. But at some point in the film — even if the film itself is bad, which it often is — you realize he’s won you over.

But it’s also worth looking at the intensity he brought to some of his early roles, before he became “Burt Reynolds.” John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) is of course the one that garnered him the acclaim, but how interesting that among that film’s lead quartet of weekend warriors, he’s the gritty, serious one. He also brings an impassioned ruthlessness to the lead role in Sergio Corbucci’s violent revenge Western Navajo Joe (1966), a movie he was reportedly not particularly fond of; it’s a wonderful film, but Corbucci had failed to do with Reynolds what his countryman Sergio Leone had done with Reynolds’s friend Clint Eastwood.

Reynolds was excellent in these parts, but something ineffable happened when he became a star. Many have noted that you can see the transformation if you look at the two fast-driving, good ol’ boy movies he made before Smokey and the Bandit. In 1973’s White Lightning, he plays a convict sprung from prison to run moonshine and help bust a corrupt Southern sheriff; it’s a sweaty, grimy performance in a predictably rough B-movie. Reynolds is laconic, smooth, sexy, but somewhat subdued. He’s still basically doing a part. In that film’s sequel, Gator (1976), which he himself directed, Reynolds is ostensibly playing the same character from White Lightning — recently released from prison again, now working with authorities to help bust an old friend who’s brought lawlessness to a small Georgia town — but something has clearly changed. He’s got the mustache now, and he spends much of the movie giggling and smiling. The movie’s a mess, but he holds it together with a jokey, modest charm that never strays into smugness. “Like a ‘gosh darn’ in a chorus of ‘motherfucker’s” was how film critic Molly Haskell described him in her amazing review of Gator, which begins with these words: “Burt Reynolds is a man not necessarily for all seasons, but surely for summer, for sunshine beer, and ice cream sodas, for drive-ins and long, lazy nights.”

The process whereby Reynolds became a bona fide supernova probably had as much to do with his ubiquitous talk-show appearances (including, famously, The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson, where he became a go-to guest host) and with that infamous Cosmo spread, as with his acting abilities. It was after the success of Gator that Reynolds and his housemate Hal Needham (who had been the star’s stunt double and second-unit director) came up with the idea for Smokey and the Bandit, which turned Reynolds into a cultural icon, a wall-breaking, wink-wink prankster who could often make his movies better through a kind of ironic detachment. This fit right in with his popularity as a self-effacing and garrulous talk-show guest. (He was even open about the fact that he’d been wearing hairpieces since the late 1960s.)

But maybe something was lost somewhere in there well. Reynolds swore after the second Smokey and the Bandit film that he wouldn’t do any more movies with cars driving above 35 mph, but Needham paid him buckets of money to do the Cannonball Run movies. In his memoir Stuntman: My Car-Crashing, Plane-Jumping, Bone Breaking, Death-Defying Hollywood Life, Needham pins the blame for Reynolds’s reluctance to do these parts on the swipes critics took at him, and seems to think Burt was just fine doing the kinds of movies Burt did. But Reynolds, for his part, was a bit more sanguine about the decisions he took in the early 1980s. He writes that a year after The Cannonball Run, he couldn’t get his phone calls returned. “I’d chosen too many films because I liked the location (‘Jamaica? I’ll take it!). Or the leading lady. Or because I’d be working with friends. If the script was crap, I rationalized that I could make it better, and I usually did, but it was just better crap. I didn’t open myself to new writers or risky parts because I wasn’t interested in challenging myself as an actor, I was interested in having a good time.”

But there was good work in this period as well. In the 1981 cop drama Sharky’s Machine (which he also directed), he plays a down-and-out Atlanta vice cop who tries to uncover a mysterious high-end prostitution ring and becomes obsessed with a young escort played by Rachel Ward. It’s a star turn — he’s still smooth when he wants to be, and his laid-back charm is still there — but you can sense in the way that he’s deglamorized his character a struggle to shift away from his fun, wise-cracking persona.

It’s a shame that Reynolds so often resented some of his best work, but maybe that comes with the territory. He was reportedly not too fond of Bill Forsyth’s Breaking In, a 1989 comedy-drama in which he plays an aging, rule-obsessed master thief who takes a brash young newcomer under his wing. And yet, Forsyth — a great Scottish director who had a knack for making touching, understated comedies about emotionally stunted man-children — had given him one of his most touching parts. Reynolds also famously clashed with Boogie Nights director Paul Thomas Anderson, and claimed not to really understand the picture. But in his memoir, he’s a bit more charitable, even as he admits he never watched the film all the way through. “As actors, we were floating around trying to figure out what we were doing there because, I think, the characters themselves are lost souls. Which makes the performances of my fellow cast members all the more remarkable.”

I keep returning to that word: honesty. And I keep returning to Burt Reynolds crying as he remembers Dinah Shore. Somewhere in that chapter, he relays a bit of advice Shore gave him. “The camera is an X-ray machine. People look inside you and decide whether they like you. If they do, there’s almost nothing you can do to change their minds.” That lucky bastard. We liked him.