Vol. 15 - Deutsches Primatenzentrum

Vol. 15 - Deutsches Primatenzentrum

Vol. 15 - Deutsches Primatenzentrum

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

LEMUR NEWS<br />

The Newsletter of the Madagascar Section of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group<br />

<strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 ISSN 1608-1439<br />

Editors<br />

Christoph Schwitzer (Editor-in-chief)<br />

Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, Bristol Zoo Gardens, UK; cschwitzer@bcsf.org.uk<br />

Claudia Fichtel<br />

German Primate Center, Göttingen, Germany; claudia.fichtel@gwdg.de<br />

Jörg U. Ganzhorn<br />

University of Hamburg, Germany; ganzhorn@biologie.uni-hamburg.de<br />

Rodin M. Rasoloarison<br />

German Primate Center, Göttingen, Germany; kirindy@simicro.mg<br />

Jonah Ratsimbazafy<br />

GERP, Antananarivo, Madagascar; gerp@wanadoo.mg<br />

Anne D. Yoder<br />

Duke University Lemur Center, Durham, USA; anne.yoder@duke.edu<br />

IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group<br />

Chairman Russell A. Mittermeier, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA<br />

Deputy Chair Anthony B. Rylands, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA<br />

Coordinator – Section on Great Apes Liz Williamson, Stirling University, Stirling, Scotland, UK<br />

Regional Coordinators – Neotropics<br />

Mesoamerica – Liliana Cortés-Ortiz, Museum of Zoology & Department of Ecology and Evolutionary<br />

Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA<br />

Andean Countries – Erwin Palacios, Conservation International Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia and<br />

Eckhard W. Heymann, <strong>Deutsches</strong> <strong>Primatenzentrum</strong>, Göttingen, Germany<br />

Brazil and the Guianas – M. Cecília M. Kierulff, Instituto para a Conservação dos Carnívoros<br />

Neotropicais – Pró-Carnívoros, Atibaia, São Paulo, Brazil, Fabiano Rodrigues de Melo, Universidade<br />

Federal de Goiás, Jataí, Goiás, Brazil, and Maurício Talebi, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Diadema,<br />

São Paulo, Brazil<br />

Regional Coordinators – Africa<br />

West Africa – W. Scott McGraw, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA<br />

Regional Coordinators – Madagascar<br />

Jörg U. Ganzhorn, Hamburg University, Hamburg, Germany, and Christoph Schwitzer, Bristol Conservation<br />

and Science Foundation, Bristol Zoo Gardens, Bristol, UK<br />

Regional Coordinators – Asia<br />

China – Long Yongcheng, The Nature Conservancy, China<br />

Southeast Asia – Jatna Supriatna, Conservation International Indonesia Program, Jakarta, Indonesia, and<br />

Christian Roos, <strong>Deutsches</strong> <strong>Primatenzentrum</strong>, Göttingen, Germany<br />

IndoBurma – Ben Rawson, Conservation International, Hanoi, Vietnam<br />

South Asia – Sally Walker, Zoo Outreach Organization, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, and Sanjay Molur,<br />

Wildlife Information Liaison Development, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India<br />

Editorial assistants<br />

Nicola Davies, Rose Marie Randrianarison<br />

Layout<br />

Heike Klensang, Anna Francis<br />

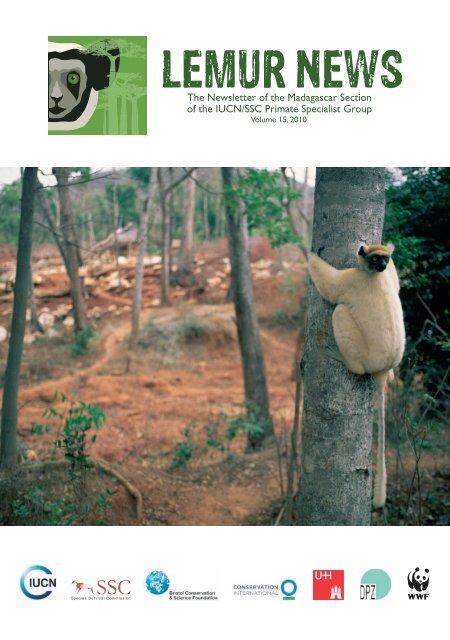

Front cover: The Endangered golden-crowned sifaka (Propithecus tattersalli) at the edge of an area devastated<br />

by gold mining activities in the Daraina region of north-eastern Madagascar. © Pete Oxford/naturepl.com<br />

Addresses for contributions<br />

Christoph Schwitzer<br />

Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation<br />

Bristol Zoo Gardens<br />

Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Fax: +44 (0)117 973 6814<br />

Email: cschwitzer@bristolzoo.org.uk<br />

Lemur News online<br />

All <strong>15</strong> volumes are available online at www.primate-sg.org, www.aeecl.org and www.dpz.eu<br />

This volume of Lemur News was kindly supported by the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation<br />

(through Conservation International’s Primate Action Fund) and by WWF Madagascar.<br />

Printed by Goltze GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen, Germany<br />

Jonah Ratsimbazafy<br />

GERP<br />

34, Cité des Professeurs<br />

Antananarivo 101<br />

Madagascar<br />

Email: gerp@wanadoo.mg

Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 Page 1<br />

Editorial<br />

I am writing this Editorial only a couple of days after another<br />

attempted (and failed) Coup d’Etat in Madagascar,in which a<br />

faction of the army tried to topple the Transition Government.<br />

For nearly two years now, since the start of the political<br />

crisis in early 2009,the country has not seen a week without<br />

demonstrations, tensions between different political<br />

parties and attempts from international mediators to get<br />

power-sharing agreements signed by all sides. Most donors,<br />

governments and multinational organisations alike, have<br />

frozen all non-humanitarian aid for Madagascar,which has led<br />

to severe funding shortages in the environmental and conservation<br />

sector. The political crisis has thus quickly turned<br />

into a full-blown environmental crisis, with large-scale illegal<br />

logging taking place mainly in eastern Madagascar (Marojejy,<br />

Masoala, Makira), and unseen levels of lemur poaching all<br />

across the island.To keep people aware of the seriousness of<br />

the situation we have decided to run another feature on<br />

Madagascar’s environmental crisis in this issue of Lemur News,<br />

with an excellent update on illegal logging by Erik Patel as<br />

well as a case study of ongoing threats to lemurs and their<br />

habitat in Sahamalaza National Park by Melanie Seiler and<br />

colleagues.<br />

The conservation situation of lemurs has also been a big concern<br />

in several presentations given at the most recent 23rd<br />

Congress of the International Primatological Society in<br />

Kyoto, Japan. The talk that I remember best was by Lemur<br />

News co-editor Jonah Ratsimbazafy, who reminded the audience<br />

in a very emotional way that scientists and conservationists<br />

working in Madagascar had a moral responsibility to<br />

respond to the "cries of the lemurs", as otherwise these<br />

would remain unheard by the Malagasy and international<br />

community.In the biennial discussion session of "Primates in<br />

Peril", the list of the world’s top 25 most endangered primates,<br />

issued jointly by the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist<br />

Group and IPS,lemurs remained a very high priority and will<br />

again make up 20% of the 25 listed species in the next biennium.Sadly,Madagascar<br />

thus retains its first place (along with<br />

Vietnam) as the country harbouring the highest number of<br />

the top 25. It can only be hoped that the political classes of<br />

Madagascar come to agree a way out of the current crisis<br />

sooner rather than later, as otherwise we run the very serious<br />

risk,during the UN Decade of Biodiversity 2011-2020,of<br />

losing a substantial proportion of the endemic biodiversity of<br />

this amazing megadiversity country.<br />

Alison Jolly with Russ Mittermeier at the IPS Lifetime Achievement<br />

Award 2010 ceremony in Kyoto. (Photo: R. Mittermeier)<br />

For a change,on a very positive note,I am thrilled to say that<br />

Alison Jolly was awarded the IPS Lifetime Achievement<br />

Award for her long-term commitment to lemur conservation<br />

and environmental education in Madagascar (see News<br />

and Announcements). My two daughters (now 4 and 2 years<br />

old) and I particularly enjoy reading Alison’s children’s book<br />

on Bitika,the mouse lemur,as,I am sure,do lots of children in<br />

Madagascar and elsewhere in the world.<br />

It is encouraging to see that this volume of Lemur News is<br />

again full of articles and short reports not only on lemur species<br />

red-listed in one of the Threatened categories (VU, EN<br />

or CR),but also on Data Deficient nocturnal species such as<br />

Mirza zaza,Lepilemur leucopus and the recently rediscovered<br />

Cheirogaleus sibreei (see the articles by Rode et al., Fish, and<br />

Blanco, respectively). As Johanna Rode and colleagues point<br />

out in their short report on Mirza zaza,Madagascar is in the<br />

unusual situation that 45 % of its primate species are redlisted<br />

as Data Deficient,which is a far higher percentage than<br />

in any other primate habitat country and mainly derived<br />

from the discovery of dozens of cryptic species in the genera<br />

Lepilemur and Microcebus over the last couple of years. Many<br />

of those species are only known from their type localities<br />

and may in fact be highly endangered. The more research is<br />

conducted and published on them, the easier it will become<br />

to assign them a conservation status and target them with<br />

conservation measures. It will require a concerted effort of<br />

the lemur research and conservation community over the<br />

next decade or so to to reduce the number of Data Deficient<br />

species to a level comparable to other regions (or, ideally, to<br />

zero).<br />

Another encouraging development is the frenzy of research<br />

and conservation activities now under way for Prolemur simus<br />

at various locations both south and north of the Mangoro<br />

River,reported by Dolch et al.as well as Rajaonson et al.in this<br />

volume. The greater bamboo lemur undoubtedly remains<br />

one of the most endangered of Madagascar’s lemurs. However,<br />

with several additional populations having been discovered<br />

over the last two years, workshops having been conducted<br />

that have led to a joint-up approach to this species’<br />

conservation,and the ex situ population having been included<br />

as an integral part of conservation efforts, I now think that<br />

we stand a real chance of saving Prolemur simus from extinction.<br />

As Jörg Ganzhorn announced in his editorial to Lemur News<br />

14, I have taken over the coordination of this newsletter<br />

from him after the 2009 volume, hence this is now the first<br />

volume that I have helped produce (which is my humble excuse<br />

for its slightly late publication). Jörg has been involved<br />

with Lemur News since its inception in 1993,first as a member<br />

of its Editorial Board and from volume 3 (1998) as its Editor.I<br />

am thus pleased to say that we will not lose his experience<br />

and backing,as he has kindly agreed to remain part of the editorial<br />

team. Likewise, Jonah Ratsimbazafy and Rodin Rasoloarison,who<br />

have been the newsletter’s Malagasy coordinators<br />

since 2006, and Anne Yoder, who represents the Duke<br />

Lemur Center, will carry on as editorial team members, for<br />

which I am grateful.I am indebted to Heike Klensang,who has<br />

been doing the layout for Lemur News now for more than a<br />

decade and is still not tired of it,and to Anna Francis,who has<br />

designed the beautiful new logo and front cover. Very many<br />

thanks also to Stephen D. Nash for the wonderful lemur silhouettes<br />

that we printed on the inside back cover.<br />

This volume of Lemur News was kindly supported by the<br />

Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation through Conservation<br />

International’s Primate Action Fund, and by the WWF<br />

Madagascar and West Indian Ocean Programme Office.

Page 2 Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010<br />

I very much look forward to helping to take Lemur News into<br />

the UN Decade of Biodiversity together with the editorial<br />

team and with its base of loyal contributors and readers,and I<br />

will do my best to ensure that the newsletter will continue to<br />

help promote the conservation of lemurs as it has done for<br />

the last 17 years.<br />

Christoph Schwitzer<br />

Feature: Madagascar’s<br />

Environmental Crisis<br />

Madagascar’s illegal logging crisis: an update<br />

and discussion of possible solutions<br />

Erik R. Patel<br />

Cornell University, 211 Uris Hall, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA,<br />

patel.erik@gmail.com<br />

How sure are you that your favorite rosewood or ebony<br />

acoustic guitar was not made from rare,illegally logged trees<br />

in Madagascar;an exceptional biodiversity hotspot with desperately<br />

little original forest remaining? What is the origin of<br />

the wood in the expensive oriental-style rosewood furniture<br />

which is heavily advertised for sale on the internet? Unfinished<br />

rosewood boards from Madagascar are openly sold<br />

even in the United States (www.gilmerwood.com/boards_<br />

rosewood-exotic_unique.htm) and the United Kingdom (www.<br />

exotichardwoods.co.uk/Woods_List/Madagascar_Rosewood.asp).<br />

Can such vendors prove that the rosewood was legally (and<br />

ethically) obtained? The answer is usually "no".These can be<br />

difficult questions for consumers to answer, but purchasing<br />

these products can prolong the ongoing logging crisis in<br />

northeastern Madagascar in some of the most unique and biologically<br />

diverse forests in the world.<br />

Consumers should be suspicious since none of these rapidly<br />

disappearing Madagascan rosewood and ebony species are<br />

yet protected under CITES,the Convention on International<br />

Trade in Endangered Species. In November of last year, Gibson<br />

Guitars, one of the two largest U.S. stringed-instrument<br />

companies,came under federal investigation for violating the<br />

Lacey Act by allegedly using illegal rosewood from Madagascar<br />

which had first been shipped to Germany and then the<br />

United States (Michaels, 2009). Most of the illegally logged<br />

rosewood in Madagascar is used for the manufacture of furniture<br />

in China. Some of this is known to be sold in China as<br />

luxurious "Ming Dynasty style" furniture (Global Witness<br />

and Environmental Investigation Agency, 2009). Some may<br />

well be exported to western countries. China is the world’s<br />

leading exporter of furniture.According to the Office of the<br />

United States Trade Representative, the United States imported<br />

16 billion dollars of Chinese furniture in 2009,making<br />

it the USA’s fifth largest import from China.<br />

Illegal logging of rosewood (Dalbergia spp.) and ebony (Diospyros<br />

spp.) has emerged as the most severe threat to Madagascar’s<br />

dwindling northeastern rainforests. In 2009, a year<br />

of political upheaval in Madagascar due to an undemocratic<br />

change of power,approximately 100,000 of these trees were<br />

illegally cut in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Masoala<br />

National Park,Marojejy National Park,the Makira Conservation<br />

Site, and Mananara Biosphere Reserve (also a national<br />

park).Needless to say,the wood is extremely valuable.Rosewood<br />

can sell for US$5,000 per cubic meter,more than double<br />

the price of mahogany.Several hundred million dollars of<br />

these precious hardwoods were cut in 2009 in protected<br />

areas. The overwhelming majority of these profits are taken<br />

by a rosewood mafia of a few dozen organizing individuals,<br />

many of whose identities are well known.Few others benefit.<br />

Harvesting these extremely heavy hardwoods is a labor intensive<br />

activity requiring coordination between local residents<br />

who manually cut the trees, but receive little profit<br />

(about US$5/day), and a criminal network of exporters, domestic<br />

transporters, and corrupt officials who initiate the<br />

process and reap most of the enormous profits. This is a<br />

"tragedy with villains" unlike habitat disturbance from subsistence<br />

slash-and-burn agriculture which has been well described<br />

as a "tragedy without villains" (Barrett et al., 2010;<br />

Débois, 2009; Global Witness and Environmental Investigation<br />

Agency,2009;Patel,2007,2009;Randriamalala and Liu,in<br />

press;Schuurman and Lowry,2009;Schuurman,2009;Wilme<br />

et al., 2009; Wilme et al., in press).<br />

Globally, illegal logging results in an estimated US$10 billion<br />

lost per year to the economies of timber producing countries<br />

(Furones, 2006). In addition to depriving the government<br />

of Madagascar of millions of dollars of taxable revenue,<br />

illegal logging of this precious wood has decimated tourism<br />

in northeastern Madagascar, which had become a growing<br />

source of local income. Although selective logging results in<br />

less absolute forest loss than clear-cutting, it is often<br />

accompanied by substantial peripheral damage such as decreases<br />

in genetic diversity and increases in the susceptibility<br />

of the impacted areas to burning and bushmeat hunting.<br />

Documented long-term ecological consequences of selective<br />

logging in Madagascar include invasion of persistent,<br />

dominant non-native plant species, impaired faunal habitat,<br />

and a diminution of endemic mammalian species richness<br />

(Gillies, 1999; Cochrane and Schultze, 1998; Brown and<br />

Gurevitch, 2004; Stephenson, 1993). In actual practice, rosewood<br />

logging has turned out to be far less "selective" than<br />

originally believed. Often rafts made of a lighter species of<br />

wood (Dombeya spp.) are constructed to float the much<br />

more dense rosewood logs down rivers. Approximately five<br />

Dombeya trees are cut as "raft wood" for every one rosewood<br />

tree (Randriamalala and Liu,in press).Tall adult trees of<br />

a variety of species, that simply happen to be very close to<br />

rosewood trees, must often be cut simply to gain access to<br />

cut down a rosewood tree. This has been observed in<br />

Marojejy (pers. obs.).<br />

Red ruffed lemurs (Varecia rubra) are probably the most negatively<br />

impacted lemur since many were hunted by these loggers<br />

and this species is known to feed on ebony trees<br />

(Diospyros spp.) as well as pallisandre (Dalbergia spp.) in<br />

Masoala (Vasey, pers. comm.). Varecia rubra probably also<br />

feeds on the fruits and leaves of the logged "raft wood"<br />

Dombeya spp. trees like Varecia v. editorium in Manombo Forest<br />

in southeastern Madagascar (Ratsimbazafy, 2007). In<br />

Mantadia National Park, Indri indri and Propithecus diadema<br />

consume young leaves of one species of actual rosewood<br />

(Dalbergai baronii) which is also consumed by Milne-Edwards’<br />

sifakas (Propithecus edwardsi) in Ranomafana National Park<br />

(Powzyk and Mowry,2003;Arrigo-Nelson,2007).Propithecus<br />

diadema at Tsinjoarivo consume the unripe fruit of ebony<br />

trees (Irwin, 2006). In Marojejy, silky sifakas (Propithecus<br />

candidus) not uncommonly feed on the young leaves of pallisandre<br />

(Dalbergia chapelieri) which is also a preferred sleeping<br />

tree (pers. obs.).<br />

When discussing the impacts of precious wood logging, it is<br />

important not to forget how damaging all this has been to local<br />

communities as well.Local residents have suffered as foreign<br />

and domestic elites have corrupted the forest service,<br />

leading to losses of sustainable employment in tourism, re-

Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 Page 3<br />

search, and conservation. In some cases, community life has<br />

suddenly changed as gambling, prostitution, and crime have<br />

increased in rural communities. Moreover, the risks of local<br />

food shortages and nutritional deficiencies mount when<br />

farmers abandon subsistence agriculture for temporary,physically<br />

dangerous illegal logging work (Global Witness and<br />

Environmental Investigation Agency,2009;Patel,2007,2009).<br />

Moreover,illegal loggers trample on the beliefs and taboos of<br />

local people.In traditional Sakalava culture,ebony is a sacred<br />

wood only cut by priests who conduct traditional ceremonies<br />

with ebony staffs. The chief of Ankalontany, a Sakalava<br />

Malagasy village in the northeast, explained that "Some<br />

strangers from outside our village came here. They started<br />

cutting ebony and they clearly had no right. We asked for<br />

their authorization but they said they didn’t have to show us<br />

papers.They said they had police clearance and we can’t stop<br />

them." Laurent Tutu, president of the forest association of<br />

Ankalontany, remarked "It hurts us to see our trees cut like<br />

this. The forest loses its personality" (Cocks, 2005).<br />

Although illegal logging in Madagascar has received some media<br />

attention recently, confusion still remains regarding a<br />

number of key facts. The aim of this report is to provide an<br />

update (at the time of writing: May 25, 2010), dispel a few<br />

myths,discuss some of the possible solutions to this ongoing<br />

crisis, and present a comprehensive bibliography of articles,<br />

photos, films, and videos related to this topic.<br />

Four myths about illegal logging in Madagascar<br />

Myth #1: "Plenty of Madagascar rosewood is harvested legally…"<br />

says Bob Taylor, founder of Taylor Guitars. Quote<br />

from Gill, C. (2010). Log Jam. Guitar Aficionado. Spring Issue.<br />

P. 68<br />

This is simply not true. A vast amount of published evidence<br />

clearly shows that very very little,if any,of the rosewood logging<br />

in Madagascar is legal.The overwhelming majority of exported<br />

Madagascar rosewood is illegally logged within Masoala<br />

National Park and Marojejy National Park (which are part<br />

of a UNESCO World Heritage Site) as well as Mananara Biosphere<br />

Reserve (also a national park) and the vast Makria<br />

Conservation Site (Barrett et al., 2010; Débois, 2009; Global<br />

Witness and Environmental Investigation Agency,2009;Patel,<br />

2007, 2009; Randriamalala and Liu, in press; Schuurman and<br />

Lowry, 2009; Schuurman, 2009; Wilme et al., 2009; Wilme et<br />

al., in press).<br />

Myth #2: The current ban has stopped illegal logging.<br />

In late March, the government of Madagascar announced a<br />

new two to five year ban on export and cutting of ebony and<br />

rosewood. The decree #2010-141 officially passed on April<br />

14, 2010. Clearly this was an important and large step forward.<br />

However, the decree does not apparently include<br />

pallisandre, a precious hardwood in the same genus (Dalbergia)<br />

as rosewood. Illegal logging of pallisandre has heavily<br />

impacted some reserves such as Betampona Natural Reserve<br />

(Kett, 2005; Bollen, 2009). At the time of writing (May<br />

25, 2010), there have been no new exports since the recent<br />

ban.However,illegal rosewood and ebony logging still continues<br />

inside Mananara Biosphere Reserve and the Makira Conservation<br />

Site according to reliable anonymous informants.<br />

The clearest information has come from Mananara where at<br />

least several hundred, recently cut, rosewood logs were observed.<br />

Myth #3: Illegal logging was never a big problem in Madagascar<br />

until the recent political crisis.<br />

Illegal logging in Madagascar of rosewood (Dalbergia spp.) and<br />

ebony (Diospyros spp.) did not begin with the culmination of<br />

the political crisis in March 2009.A major illegal logging crisis<br />

in World Heritage Sites (Masoala National Park and Marojejy<br />

National Park) took place during 2004-2005,a time of political<br />

stability. The earliest documented case of rosewood logging<br />

in Madagascar and foreign export dates to 1902.Foreign<br />

exports of Madagascar rosewood occurred at "low" levels<br />

(1000 to 5000 tonnes) between 1998 and 2007. In 2008, exports<br />

jumped to 13,000 tonnes,and jumped again in 2009 to<br />

more than 35,000 tonnes (Botokely,1902;Randriamalala and<br />

Liu,in press;Global Witness and Environmental Investigation<br />

Agency, 2009).<br />

Myth #4: There are 43 species of rosewood trees in Madagascar.<br />

Some recent reports had mistakenly made this statement. It<br />

is not entirely clear exactly how many rosewood species are<br />

found in Madagascar. More botanical research is needed.<br />

However, currently, there are believed to be 10 species of<br />

rosewood in Madagascar in the genus Dalbergia which contains<br />

48 total species. The rosewood species are presumed<br />

to be Dalbergia baronii [VU], D. bathiei [EN], D. davidii [EN],D.<br />

louvelii [EN], D. mollis [NT], D. monticola [VU], D. normandii<br />

[EN], D. purpurascens [VU], D. tsiandalana [EN], and D. viguieri<br />

[VU] (Barrett et al., 2010).<br />

Rosewood stockpile solutions?<br />

Approximately 10,280 tonnes of illegally logged rosewood<br />

remain stockpiled in numerous locations in northeastern<br />

Madagascar, such as the ports of Vohemar and Antalaha as<br />

well as private residences in those cities and Sambava,<br />

Ampanifena,Ambohitralalana,and others.Each <strong>15</strong>0 kg log has<br />

an approximate market value of US$1,300 usd.As unfinished<br />

logs, the value of the current stockpile is therefore approximately<br />

US$90 million.Value increases dramatically,of course,<br />

after being constructed, for example, into high-end Ming<br />

Dynasty style furniture in China.A single armoire composed<br />

of only a few logs can sell for US$20,000 or more.It’s a horrid<br />

contrast to the annual income in Madagascar (about<br />

US$400) or the daily wage provided to loggers (US$5) for<br />

the dangerous and physically debilitating work (Randriamalala<br />

and Liu, in press; Global Witness and Environmental<br />

Investigation Agency, 2009; anonymous local informants).<br />

If the export ban holds (numerous other bans did not),what<br />

should be done with these stockpiles? Several ideas have<br />

been suggested.<br />

1. The "Forest Counterpart Fund" (Wilme et al., 2009) aims<br />

to create a conservation and charitable works fund to assist<br />

local communities and forests damaged by the illegal logging.<br />

The logs are not sold on the open market as in the second<br />

proposal below.Rather,philanthropists,conservation organizations,<br />

and international aid agencies pay to "adopt" a log.<br />

Each log can be "adopted" for its market value (about<br />

US$1,300). The logs themselves are given to (carefully selected)<br />

local residents who are victims of the illegal logging.<br />

The logs would then be carved,engraved,and customized for<br />

public display as symbols. If sufficient donors can be found,<br />

this proposal offers a win-win solution for Madagascar’s forests<br />

as well as people.<br />

2. The Moratorium-Conservation-Amnesty-Reforestation<br />

(MCAR) program (Butler, 2009). This is essentially a one-off<br />

actual sale with conservation benefits. Logs would be auctioned<br />

via a transparent market system in which the price<br />

and the log code would be recorded, publicly available, and<br />

digitally traceable.Funds generated would mainly go towards

Page 4 Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010<br />

conservation programs such as reforestation and forest<br />

monitoring. Criminal traders would receive amnesty from<br />

prosecution as well as a very small percentage of the funds.<br />

An export moratorium would be required.There is always a<br />

danger that one-off sales can encourage further logging; a<br />

topic which has been extensively debated with respect to<br />

confiscated elephant ivory stockpiles. An impressive recent<br />

review paper in Science (Wasser et al., 2010):<br />

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/short/327/5971/1331)<br />

argued that no one-off ivory sales should be approved even if<br />

the funds go towards conservation.<br />

3. Destroy the stockpile. This was recently reiterated by<br />

Global Witness (GW) and Environmental Investigation<br />

Agency (EIA). Andrea Johnson, Director of Forest Campaigns<br />

at EIA explained that "To end the cycle of illegal harvest<br />

and corruption, the government should take the step of<br />

destroying all stocks that are not contained in the latest official<br />

inventories…Traders, who are currently stockpiling illegal<br />

timber, hoping for another ‘exceptional’ export authorization,must<br />

receive a clear signal that it will be impossible to<br />

profit from the illegal trade in the future." Numerous examples<br />

can be found from around the world of simple and effective<br />

destruction of stockpiles of contraband such as small<br />

arms,drugs,and ivory.Destruction also eliminates the not insignificant<br />

expense of storing and guarding the items.Burning<br />

the rosewood stockpiles would create a lot of pollution, it<br />

has been argued, and might be dangerous given the high volume.<br />

Other ways of destroying the wood are possible however.<br />

The wood could be hacked into tiny unusable pieces.<br />

This is already done sometimes by park rangers in Madagascar.<br />

This would take a very long time, but would be a fitting<br />

punishment of hard labor for members of the rich rosewood<br />

mafia! Of course, destruction of the wood, whatever the<br />

method,would contribute no money for any conservation or<br />

community development funds.<br />

Any of these possibilities are better than what has happened<br />

in the past:seized wood was auctioned off to the highest bidder.Foreign<br />

export remains a possibility too,despite the ban.<br />

French shipping company CMA-CGM Delmas exported<br />

rosewood from Madagascar several times in 2009 and 2010.<br />

Long-term solutions?<br />

Thinking long-term, what can be done to prevent another illegal<br />

logging crisis in Madagascar?<br />

Some may argue that so little rosewood and ebony remains,<br />

logging on this scale could never happen again.However,this<br />

had been claimed before 2009 too. More surveys are clearly<br />

needed. One hopes that some of the more impenetrable regions<br />

of mountainous Marojejy National Park may still have<br />

rosewood. But because rosewood tends to be harvested at<br />

lower elevations, near rivers (where the largest individuals<br />

are found), it is less protected by the physical challenges of<br />

the massif than some other tree species. It is encouraging<br />

that some Dalbergia and Diospyros species can form stump<br />

sprouts which can grow into a new tree over many many<br />

years. Unfortunately, some entire rosewood stumps are removed<br />

either to hide evidence of logging or for wood for<br />

small, locally made rosewood vases. Rosewood trees are<br />

known to be some of the oldest trees in the eastern Malagasy<br />

humid forests. They can live to be more than 400 years old,<br />

according to local guides. Traders explain that they can be<br />

harvested after 50 years (Patel 2007, 2009).<br />

1. CITES<br />

The surest way to reduce the likelihood of another illegal<br />

logging crisis in Madagascar, is to list all species in the genera<br />

of Dalbergia and Diospyros on CITES Appendix 1. Currently<br />

none of Madagascar’s ebony or rosewood species are protected<br />

under any appendices within the Convention on International<br />

Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Globally,<br />

only one species of rosewood,Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia<br />

nigra), is listed under CITES Appendix 1. This is the most<br />

stringent category,and prohibits all commercial trade of that<br />

wood from the date of listing. This has generally been effective.Guitars<br />

in the United States made of Brazilian rosewood<br />

are known to have risen in price and are harder to find since<br />

Appendix 1 listing. Similarly, Appendix 1 listing of Alerce<br />

(Fitzroya cupressoides),a heavily logged South American conifer,<br />

has significantly reduced logging and trade (Barrett et al.,<br />

2010; Keong, 2006).<br />

A few other Brazilian and Central American rosewood species<br />

are listed under CITES Appendix 2 and 3. These lower<br />

appendices aim to regulate trade,not prohibit it.Just this year,<br />

another species of Brazilian rosewood (Aniba rosaeodora),exported<br />

extensively as fragrant oil, was listed under CITES<br />

Appendix 2. Two additional species of Central American<br />

rosewood (D. retusa and D. stevensonii) are listed under Appendix<br />

3. Appendix 2, unlike Appendix 3, does require that<br />

the CITES authorities in the export nation determine that<br />

the species were legally obtained and that their export will<br />

not be detrimental to species survival.There seem to be few<br />

cases where Appendix 3 listing was sufficient, except as a<br />

means to Appendix 2 or higher listing. The well examined<br />

case-studies of big-leaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and<br />

ramin (Gonystylus spp.) both began as Appendix 3 species<br />

(which only requires unilateral listing by a habitat country)<br />

and were later voted in as Appendix 2 species by the CITES<br />

parties (Keong, 2006).<br />

To what degree can CITES regulations be implemented and<br />

enforced? The need for more officially trained import inspectors<br />

has been suggested numerous times. The agency<br />

chosen as the CITES management authority should be free<br />

of corruption and have experience in forest management.<br />

Insufficient trained staff has also hindered the ability of export<br />

authorities to determine whether an Appendix 2 species<br />

was legally obtained and non-detrimental to species survival.Range<br />

countries often require assistance in this respect.<br />

An unusually good example comes from Indonesia where biological<br />

data for ramin has been used in non-detriment findings<br />

to examine sustainability. Missing "certificates of origin"<br />

have been a problem for some Appendix 3 species. While<br />

ramin and big-leaf mahogany were listed on Appendix 3, the<br />

required ‘certificates of origin’ were not consistently issued<br />

by exporting nations;while importing countries were not always<br />

diligent about confirming that shipments arrived with<br />

such certificates (Blundell, 2007; Keong, 2006).<br />

2. Independent forest monitoring (IFM)<br />

In addition to CITES,actual improvements in forest monitoring<br />

on the ground are needed. A new system called independent<br />

forest monitoring (IFM) may be needed in order<br />

stop illegal logging, monitor implementation of REDD (Reducing<br />

Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Destruction)<br />

programs, restore the confidence of international donors,<br />

and ultimately to save Madagascar’s precious forests as<br />

well as attain social justice for Madagascar’s impoverished<br />

population. IFM has been defined as "the use of an independent<br />

third party that,by agreement with state authorities,provides<br />

an assessment of legal compliance, and observation of<br />

and guidance on official forest law enforcement systems"<br />

p. 18 (Global Witness,2005). IFM is similar in principle to unbiased<br />

international election observers. Local and international<br />

expertise is utilized, and monitoring teams operate

Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 Page 5<br />

independently but with the consent of the host government.<br />

Independent forest monitors are strictly observers, law enforcement<br />

remains the responsibility of local officials and<br />

governments.<br />

Of course other nations have been faced with similar forest<br />

monitoring problems.IFM has already been used successfully<br />

in several African and Central American nations seeking to<br />

improve the effectiveness of their forest monitoring. Since it<br />

was first introduced in 1999, IFM has been established in<br />

Cameroon, Cambodia, and Honduras. Smaller scale feasibility<br />

and pilot studies have been conducted in Ghana, Peru,<br />

Mozambique, Republic of Congo, Tanzania, and Democratic<br />

Republic of Congo. In Cambodia and Cameroon, donor<br />

countries have been the impetus behind IFM.Though in Honduras,the<br />

incentive for IFM was domestic,and hosted by the<br />

Honduran Commission for Human Rights (CONADEH).<br />

Furones (2006) and Young (2007) review the results of IFM in<br />

these nations, and consider them to be "broadly positive".<br />

Specific examples of the impact of IFM in these nations include:documentation<br />

of hundreds of forest crimes,cancellation<br />

of logging concessions,moratoriums on logging and timber<br />

transport,and creation of new "forest crimes monitoring<br />

units" in the forestry administrations. In some cases,IFM has<br />

earned money for these governments by identifying violations<br />

which led to large fines against logging companies and<br />

individuals breaching the law and forest management regulations.<br />

3. Update IUCN Red List assessments<br />

The approximately 10 Madagascar rosewood species listed<br />

above have not had their official conservation status evaluated<br />

by the IUCN since 1998. At that time, all were threatened<br />

except for D. mollis.Five of the ten were already classified<br />

as ‘endangered’ then. Given the extreme logging since<br />

that time, it is likely that their Red List categories should be<br />

reassessed (IUCN, 2010).<br />

4. UNESCO World Heritage Sites "in danger"<br />

The majority of the illegally logged rosewood in Madagascar<br />

comes from two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Masoala<br />

National Park and Marojejy National Park.Why have Masoala<br />

and Marojejy not been placed on the World Heritage Sites<br />

"In Danger" List? After all,2010 is the United Nations "International<br />

Year of Biodiversity". Nine national parks and seven<br />

other protected natural areas are currently on this danger<br />

list, mainly for extensive anthropogenic disturbance such as<br />

poaching, logging, and war. The extent of the logging damage<br />

in Masoala National Park, in particular, over the past 5 years,<br />

must rival that of some of the other national parks "in danger".<br />

Placing a site on the UNESCO "danger list" is not utter<br />

de-listing. It is a reversible process meant to draw attention<br />

to and attract possible resources which can alleviate the crisis.There<br />

are specific funds that can become available if a site<br />

is placed on the danger list. One can only speculate that the<br />

reasons for no change in status may well be political and<br />

practical. Perhaps it complicates matters that eight national<br />

parks (which include these two) comprise the single Atsinanana<br />

World Heritage Site Complex. Perhaps there are<br />

fears of triggering an even greater loss of tourism.Whatever<br />

the reasons may be, it is odd that UNESCO has not been<br />

more vocal or active in its support of these two national<br />

parks which are the biodiversity jewels of the Atsinanana<br />

World Heritage Site Complex (IUCN, 2007).<br />

5. DNA fingerprinting<br />

DNA fingerprinting has recently been used on confiscated<br />

ivory to determine which populations of African elephants<br />

were slaughtered. Similar genetic techniques would be of<br />

great assistance in determining which populations of Madagascar<br />

rosewood are being logged the most,and in identifying<br />

species. DNA testing has already been used to track timber,<br />

but not yet in Madagascar.One of the biggest methodological<br />

challenges is extracting DNA from the heartwood of dead<br />

tree trunks (e.g., rosewood stockpiles), which consist of<br />

dead cells with partly degraded DNA. In living trees, it is a<br />

routine process to obtain DNA from the cambium just beneath<br />

the bark or leaves or buds. Nevertheless, several new<br />

techniques have successfully extracted DNA from dry wood<br />

of ramin (Gonystylus spp.) and other woods including 1000<br />

year old beech (Fagus spp.) (Nielson and Kjaer, 2008).<br />

References and rosewood logging resources<br />

Barrett, M.A.; Brown, J.L.; Morikawa, M.K.; Labat, J-N.; Yoder,<br />

A.D. In press. CITES designation for endangered rosewood<br />

in Madagascar. Science.<br />

Blundell,A.G.2007.Implementing CITES regulations for timber.<br />

Ecological Applications 17: 323-330.<br />

Bohannon, J. 2010. Madagascar’s forests get a reprieve – But<br />

for how long? Science 328: 23-25.<br />

Bollen, A. 2009. Eighth continent quarterly. The Newsletter<br />

of the Madagascar Fauna Group.Autumn Issue.<br />

Bosser, J.; Rabevohitra, R. 1996. Taxa et noms nouveaux dans<br />

le genre Dalbergia (Papilionaceae) à Madagascar et aux<br />

Comores. Bulletin du Museum national d'Histoire Naturelle,<br />

4e sér., 18: 171-212.<br />

Bosser,J.;Rabevohitra,R.2005.espèces nouvelles dans le genre<br />

Dalbergia (Fabaceae, Papilionoideae) à Madagascar.<br />

Adansonia, Sér. 3, 27, 2: 209-216.<br />

Botokely (Marc Clique).1902.Chronique commerciale,industrielle<br />

et agricole. Revue de Madagascar 4: 356-365.<br />

Braun, D. 2009. Lemurs, rare forests, threatened by Madagascar<br />

strife. NatGeo News Watch.<br />

blogs.nationalgeographic.com/blogs/news/chiefeditor/<br />

2009/03/lemurs-threatened-by-madagascar-strife.html.<br />

Downloaded on 23 March 2009.<br />

Braun, D. 2010. Conservationists applaud renewed ban on<br />

Madagascar rosewood. NatGeo News Watch.<br />

blogs.nationalgeographic.com/blogs/news/chiefeditor/2010/<br />

03/madagascar-rosewood-ban-reaction.html. Downloaded on<br />

31 March 2010.<br />

Brown,K.A.;Gurevitch,J.2004.Long-term impacts of logging<br />

on forest diversity in Madagascar. Proceedings of the National<br />

Academy of Sciences 101: 6045-6049.<br />

Butler, R. A. 2010. How to end Madagascar’s logging crisis.<br />

news.mongabay.com/2010/0211-madagascar.html. Downloaded<br />

on 10 February 2010.<br />

Cochrane,M.A.;Schulze,M.D.1998.Forest fires in the Brazilian<br />

Amazon. Conservation Biology 12: 948-950.<br />

Cocks, T. 2005. Loggers cut madagascan rainforest with impunity.<br />

Reuters. July 4.<br />

Débois, R.2009. La fièvre de l’or rouge saigne la forêt malgache.<br />

Univers Maoré 13: 8-<strong>15</strong>.<br />

Du Puy, D. J.; Labat, J.-N.; Rabevohitra, R.;Villiers, J.-F.;Bosser,<br />

J.; Moat, J. 2002. The Leguminosae of Madagascar. Royal<br />

Botanic Gardens, Kew, U.K.<br />

Furones, L. 2006. Independent forest monitoring: Improving<br />

forest governance and tackling illegal logging and corruption.<br />

Trócaire Development Review 135-148.<br />

Gerety, R.M. 2010. Major international banks, shipping companies,<br />

and consumers play key role in Madagascar’s logging<br />

crisis.<br />

news.mongabay.com/2009/12<strong>15</strong>-rowan_madagascar.html.<br />

Downloaded on 16 December 2010.<br />

Gill, C. 2010. Log Jam. Guitar Aficionado. Spring Issue.<br />

Gillies, A.C.M. 1999. Genetic diversity in Mesoamerican populations<br />

of mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), assessed<br />

using RAPDs. Heredity 83: 722-732.<br />

Global Witness and Environmental Investigation Agency.<br />

2009.Investigation into the illegal felling,transport and export<br />

of precious wood in SAVA Region Madagascar. Unpublished<br />

report to the Government of Madagascar.

Page 6 Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010<br />

www.illegal-logging.info/uploads/madagascarreportrevi<br />

sedfinalen.pdf. Downloaded on 20 November 2010.<br />

Irwin, M. T. 2006. Ecological impacts of forest fragmentation<br />

on diademed sifakas (Propithecus diadema) at Tsinjoarivo,<br />

Eastern Madagascar:Implications for conservation in fragmented<br />

landscapes. Ph.D. thesis, Stony Brook University,<br />

New York, USA.<br />

IUCN. 2007. World heritage nomination. IUCN technical<br />

evaluation. Rainforests of the Atsinanana (Madagascar).<br />

IUCN Evaluation Report. ID No. 1257.<br />

IUCN. 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version<br />

3.1. www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 25 May 2010.<br />

Keong,C.H.2006.The role of CITES in combating illegal logging:<br />

Current and Potential. Traffic Online Report Series,<br />

No. 13. www.illegal-logging.info/item_single. php? it_id=<br />

504&it=document. Downloaded on 20 November 2010.<br />

Kett, G. 2005. Checking the reserve. Monthly from Madagascar.<br />

March. Madagascar Fauna Group.<br />

Labat, J.N.; Moat, J. 2003. Leguminosae (Fabaceae). Pp. 346-<br />

373. In: S.M. Goodman; J.P. Benstead (eds.) The Natural<br />

History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press, Chicago,<br />

USA.<br />

Michaels, S. 2009. Gibson guitars raided for alleged use of<br />

smuggled wood. www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/nov/<br />

20/gibson-guitars-raided. Downloaded on 20 November<br />

2009.<br />

Nielsen, L.R.; KjFr, E.D. 2008. Tracing timber from forest to<br />

consumer with DNA markers. Danish Ministry of the<br />

Environment, Forest and Nature Agency.<br />

www.skovognatur.dk/udgivelser. Electronic Publication.<br />

Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2010. US-<br />

China trade facts. www.ustr.gov/countries-regions/china.<br />

Downloaded on 23 May 23 2010.<br />

Patel, E.R. 2007. Logging of rare rosewood and pallisandre<br />

(Dalbergia spp.) within Marojejy National Park, Madagascar.<br />

Madagascar Conservation and Development 2(1):<br />

11-16.<br />

www.erikpatel.com/Logging_of_Rosewood_Patel_2007.pdf.<br />

Electronic Publication.<br />

Patel, E.R. In press. A tragedy with villains: Severe resurgence<br />

of selective rosewood logging in Marojejy National Park<br />

leads to temporary park closure. Lemur News.<br />

Patel,E.R.;Rasarely,E.;Tegtmeter,R.;Furones,N.;Fritz-Vietta,<br />

N.; Malan, S.; Waeber, P. In Prep. Beyond Ecological Monitoring:<br />

A proposal for "Independent Forest Monitoring"<br />

in Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation and Development.<br />

Randriamalala,H.;Liu,Z.In press.Bois de rose de Madagascar:<br />

Entre democratie et protection. Madagascar Conservation<br />

and Development.<br />

Ratsimbazafy, J. 2006. Diet composition, foraging, and feeding<br />

behavior in relation to habitat disturbance: Implications<br />

for the adaptability of ruffed lemurs (Varecia v.editorium)<br />

in Manombo forest, Madagascar. Pp. 403-422. In L. Gould;<br />

M.L.Sauther,(eds.) Lemurs:ecology and adaptation.Springer,<br />

New York.<br />

Rubel, A.; Hatchwell, M.; Mackinnon, J.; Ketterer, P. 2003. Masoala–L’oeil<br />

de la Forêt. Zoo Zurich.<br />

Schuurman, D.; Lowry, P.L. 2009. The Madagascar rosewood<br />

massacre. Madagascar Conservation and Development<br />

4(2): 98-102. www.mwc-info.net. Electronic Publication.<br />

Schuurman,D.2009.Illegal logging of rosewood in the rainforests<br />

of northeast Madagascar. TRAFFIC Bulletin 22(2):<br />

49.<br />

Stasse, A. 2002. La Filière Bois de Rose. Région d’Antalaha –<br />

Nord-est de Madagascar. Thèse de mastère non publiée,<br />

Université de Montpellier, France.<br />

Stephenson, P.J. 1993. The small mammal fauna of Reserve<br />

Speciale d’Analamazaotra, Madagascar: The effects of<br />

human disturbance on endemic species diversity. Biodiversity<br />

and Conservation 2: 603-6<strong>15</strong>.<br />

Wasser, S.; Poole, J.; Lee, P.; Lindsay, K.; Dobson, A.; Hart, J.;<br />

Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Wittemyer, G.; Granli, P.; Morgan, B.;<br />

Gunn,J.;Alberts,S.;Beyers,R.;Chiyo,P.;Croze,H.;Estes,R.;<br />

Gobush,K.;Joram,P.;Kikoti,A.;Kingdon,J.;King,L.;Macdonald,<br />

D.; Moss, C.; Mutayoba, B.; Njumbi, S.; Omondi, P.;<br />

Nowak, K. 2010. Elephants, ivory, and trade. Science 327<br />

(5971): 1331-1332.<br />

Wilmé,L.;Schuurman,D.;Lowry II,P.P.In Press.A forest counterpart<br />

fund:Madagascar’s wounded forests can erase the<br />

debt owed to them while securing their future, with support<br />

from the citizens of Madagascar. Lemur News.<br />

Wilmé, L.;Schuurman,D.; Lowry II, P.P.; Raven, P.H. 2009. Precious<br />

trees pay off – but who pays? Poster prepared for<br />

the World Forestry Congress in Buenos Aires,Argentina.<br />

www.mwc-info.net/en/services/Journal_PDF%27s/<br />

Issue4-2/MCD_2009_vol4_iss2_rosewood_massacre_<br />

Supplementary_Material.pdf. Downloaded on 23 October<br />

2009.<br />

Young, D. 2007. Independent forest monitoring: Seven years<br />

on. International Forestry Review 9(1): 563-574.<br />

Rosewood logging photos<br />

Photographer Toby Smith:<br />

www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/photography/7625511/<br />

Madagascar-undercover-slideshow.html<br />

Photographer Chris Maluszynsk:<br />

www.photoshelter.com/c/moment/gallery/ Rosewood-loggingin-Madagasar-by-Chris-<br />

Maluszynski/ G0000JWMAJa78LJ0/<br />

Rosewood logging films<br />

Dan Rather Reports:Treasure Island.Episode 437.A detailed<br />

investigation of the impact of the recent political crisis in<br />

Madagascar on the unique biodiversity of this island continent.<br />

Filmed in high-definition, active rosewood logging<br />

camps are shown. The impact of such habitat disturbance on<br />

the silky sifaka and the World Heritage Sites of Marojejy NP<br />

and Masoala NP are discussed. The debates surrounding the<br />

Ambatovy nickel mine adjacent to Andasibe-Mantadia NP<br />

are also discussed. The mine may be endangering one of the<br />

rarest animals on earth,the greater bamboo lemur (Prolemur<br />

simus) which is being protected there by the NGO Mitsinjo.<br />

Aired on HD-NET cable television November 2009. Purchasable<br />

and downloadable on I-Tunes in the United States.<br />

DVDs can be purchased online:<br />

hdnet-store.stores.yahoo.net/danrare437.html<br />

Sample Clip 1:<br />

www.facebook.com/video/video.php?v= 600388589544<br />

Sample Clip 2: www.youtube.com/watch?v= dEi-yRlJ-mk<br />

Carte Blanche: Madagascar (Part 1 and Part 2). Two short<br />

films examining illegal rosewood logging in Madagascar and<br />

the impact on the critically endangered silky sifaka. They<br />

were produced by Neil Shaw and commissioned and funded<br />

by Carte Blanche which is one of the most respected television<br />

news programs in the Southern Hemisphere. Aired on<br />

South African Television in April,2010,and streams freely online<br />

here:<br />

Carte Blanche: Madagascar Part 1:<br />

beta.mnet.co.za/carteblanche/Article.aspx?Id= 3919&ShowId=1<br />

Carte Blanche: Madagascar Part 2:<br />

beta.mnet.co.za/mnetvideo/browseVideo.aspx?vid=25570<br />

506: Bois de Rose. A Documentary Film by Joseph Areddy.<br />

2003. RSI, Comano/Signe, Genve/GAP, Antananarivo.<br />

Rosewood logging videos<br />

Madagascar Rainforest Massacre (English):<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FzWNPHBRrAc<br />

Madagascar Rainforest Massacre (French):<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtjmFWpGNKs&feature=related<br />

Madagascar Rainforest Massacre (Malagasy):<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHYYhhLHeQw&feature=related

Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 Page 7<br />

Global Witness – Environmental Investigation Agency - Illegal<br />

logging in Madagascar – Part 1<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1hPviSbRcU<br />

Global Witness – Environmental Investigation Agency - Illegal<br />

logging in Madagascar – Part 2<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=LBtsNBpWW0E<br />

Global Witness – Environmental Investigation Agency - Illegal<br />

logging in Madagascar – Part 3<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=payUUJed0dc<br />

Global Witness – Environmental Investigation Agency - Illegal<br />

logging in Madagascar – Part 4<br />

www.youtube.com/watch?v=lm6a6Hrat3o<br />

Rosewood logging radio programs<br />

BBC World Service – Africa. September 17, 2009.<br />

www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/2009/09/090917_<br />

madge_rosewood2.shtml<br />

Ongoing threats to lemurs and their habitat<br />

inside the Sahamalaza - Iles Radama<br />

National Park<br />

Melanie Seiler 1,2, Guy H. Randriatahina 3, Christoph<br />

Schwitzer 1*<br />

1Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, Bristol Zoo<br />

Gardens, Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA, UK<br />

2University of Bristol, School of Biological Sciences, Woodland<br />

Road, Bristol BS8 1UG, UK<br />

3Association Européenne pour l’Etude et la Conservation<br />

des Lémuriens (AEECL), Lot: IVH 169 N Ambohimanandray,<br />

Ambohimanarina, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar<br />

*Corresponding author: cschwitzer@bcsf.org.uk<br />

The Sahamalaza - Iles Radama National Park,officially inaugurated<br />

in July 2007 and managed by Madagascar National<br />

Parks (MNP), includes both marine and terrestrial ecosystems<br />

and is the first park that was created under the<br />

"Programme Environnemental III" of the Malagasy government<br />

and the World Bank. In addition to the few remaining<br />

forest fragments of the Southern Sambirano ecoregion, the<br />

park is home to extensive mangrove forests, which harbour<br />

their own highly endangered fauna, and also includes offshore<br />

coral reefs. In 2003, researchers from the Cologne<br />

Zoo, funded by AEECL, undertook an expedition to Sahamalaza<br />

to explore the opportunities for the establishment of<br />

a permanent field station in order to study and protect the<br />

Critically Endangered blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons)<br />

and its habitat.In 2004 and 2005,the field station in the<br />

Ankarafa Forest became reality (Schwitzer et al.,2006),and it<br />

has since been used by both European and Malagasy scientists<br />

as a basis for research on E. flavifrons and other lemur<br />

species, especially the Sahamalaza sportive lemur (Lepilemur<br />

sahamalazensis) and the northern giant mouse lemur (Mirza<br />

zaza),occurring on the Sahamalaza Peninsula (Schwitzer and<br />

Randriatahina, 2009).<br />

Sahamalaza - Iles Radama National Park lies within a transition<br />

zone between the Sambirano region in the north and<br />

the western dry deciduous forest region in the south, harbouring<br />

semi-humid forests with tree heights of up to 30m<br />

(Schwitzer et al.,2006).The forests include a mixture of plant<br />

species typical of both domains (Birkinshaw, 2004), and the<br />

remaining primary and secondary forest fragments vary in<br />

their degree of degradation. There are no larger connected<br />

areas of intact primary forest left on the Sahamalaza Penin-<br />

sula, and the remaining fragments all show some degree of<br />

anthropogenic disturbance and/or edge effects (Schwitzer et<br />

al., 2007). The forests and forest fragments are separated by<br />

grass savannah and shrubs. Sahamalaza is the only protected<br />

area that harbours the blue-eyed black lemur,the Sahamalaza<br />

sportive lemur and the northern giant mouse lemur. Other<br />

lemur species in the park include the aye-aye (Daubentonia<br />

madagascariensis), the western bamboo lemur (Hapalemur<br />

occidentalis),and an as yet unidentified species of dwarf lemur<br />

(Cheirogaleus spec.).<br />

The remaining forest of the Sahamalaza Peninsula and its<br />

unique fauna are in grave danger of disappearing.The habitat<br />

is already extremely degraded, nonetheless bush fires and<br />

tree-felling are activities that are routinely pursued and accepted<br />

within the local society (Ruperti et al., 2008). During<br />

the first field season of a study on the impact of habitat degradation<br />

and fragmentation on the ecology and behaviour of<br />

the Sahamalaza Peninsula sportive lemur (Lepilemur sahamalazensis),<br />

conducted by MS in 2009, local people from the<br />

villages surrounding the protected area were found logging<br />

trees in the already small forest fragments almost on a daily<br />

basis. Logging activities mainly occurred in forest fragments<br />

where no researchers had been present in previous years.<br />

During walks through different forest fragments, in addition<br />

to large numbers of logged trees, two places where trees<br />

were processed for further use were found. Trees were<br />

felled mainly in the early morning hours,on the one hand because<br />

of the high temperatures later in the day, on the other<br />

hand probably because of the assumption that the researchers<br />

started observing animals later in the day and therefore<br />

would not realise the illegal logging activities. Nonetheless,<br />

trees were sometimes also felled in the afternoons. Because<br />

locals immediately fled when becoming aware of researchers’<br />

presence, we believe that the presence of researchers<br />

and/or field guides, park authorities or park rangers is a crucial<br />

factor in stopping illegal logging in the remaining fragments.For<br />

the next field season (2010) we therefore plan to<br />

expand the observations of Lepilemur to other, not yet used<br />

forest fragments to help prevent their destruction. Of<br />

course this cannot be a long-term solution to this problem.<br />

The presence of park rangers and further environmental education<br />

of the local people will thus be extremely important<br />

to save the Sahamalaza forests from further degradation.<br />

About five times between August and October 2009, fires<br />

occurred near the Ankarafa field station, three times in the<br />

savannah and twice in the forest itself. After having extin-<br />

Fig. 1: Lepilemur sahamalazensis<br />

poached<br />

and roasted by locals in<br />

Sahamalaza - Iles Radama<br />

National Park“.

Page 8 Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010<br />

guished these fires it became obvious that they had all<br />

started right beside the fire breaks that are frequently used<br />

as paths by people on their way between villages. The Ankarafa<br />

field guides, all of them locals from the surrounding villages,<br />

assumed that the fires were set by villagers to show<br />

their dissatisfaction with the recently established national<br />

park that prohibits the use of the forests for collecting building<br />

material for their dwellings. As we followed the smoke<br />

that was coming from another fire, we found an area inside<br />

one of the core zones of the national park that was inhabited<br />

by a young couple. They harvested a rice field and regularly<br />

burned undergrowth around it. Additionally, they kept cattle<br />

and goats and had built 2 houses at this site,one for the cattle<br />

and one for themselves. As we talked to them, they claimed<br />

that they were allowed to stay on this site and that MNP had<br />

sold this part of the forest to them.They affirmed that,if they<br />

set fire on this site, they would keep an eye on it and would<br />

prevent the fire from expanding into the forest. Unfortunately<br />

this was not the case,however,as we later observed a<br />

fire around this site without anyone near it. Overall, it<br />

seemed that there were various people living inside the national<br />

park on permits given to them by what they claimed to<br />

have been MNP agents;we were told that there was a map of<br />

the park showing all the "excluded" areas available for housing<br />

and agriculture, which could be seen in the village of<br />

Marovato. If that was indeed the case (we did not have the<br />

opportunity to verify the information),it would be a massive<br />

problem for protecting Sahamalaza’s unique wildlife and forests.<br />

If people claiming to be MNP staff illegally sold permits<br />

for activities inside the national park, the destruction of the<br />

small forest fragments will continue rapidly.<br />

Another big problem comes with cattle; every day zebu cattle<br />

were observed in all forest fragments and on the savannah<br />

in Ankarafa, as people from nearby villages let their cattle<br />

roam freely.The abundance of zebu themselves and their excrements<br />

indicated that they frequently used the forest fragments<br />

as grazing grounds, especially those with remaining<br />

primary forest parts. When zebu were grazing in the forest<br />

rather than on the savannah, their movements were accompanied<br />

by crashing and breaking sounds;they were undoubtedly<br />

hindering the growth of many saplings,if not eating them.<br />

This is an additional threat to the forest fragments, and furthermore,<br />

the abundance of the excrements of local zebu<br />

has been found to negatively correlate with the density of L.<br />

sahamalazensis (Ruperti, 2007). Additionally, the introduced<br />

bush pig is responsible for considerable habitat destruction<br />

due to digging up large areas, thus hindering the growth of<br />

saplings. Unfortunately, the bush pig is reproducing wildly as<br />

it is regarded as fady (taboo) by the local people and therefore<br />

not hunted.<br />

Not only the activities of local people seem to be a threat to<br />

the endangered wildlife on the Sahamalaza Peninsula.One of<br />

the Ankarafa field guides encountered a foreigner,probably a<br />

resident living in Madagascar (since he spoke Malagasy fluently),<br />

with a 4x4 car and two local guides about 1 km from<br />

the researchers’ camp. These people had set up a tent and<br />

told the Ankarafa field guide that they were visiting all villages<br />

on the Sahamalaza Peninsula to look for fish. As we checked<br />

their camp site the next day, the three men were gone, but<br />

signs of a fire,logged branches and feathers of a harrier hawk<br />

were found,indicating that they had caught and killed this endangered<br />

bird of prey. We wrote a report about this event<br />

and handed it over, together with feathers of the bird, to<br />

MNP in Maromandia. However, as long as there are no signs,<br />

borders or fences indicating the national park area and its<br />

restrictions, these problems will continue.<br />

The ongoing political crisis is a further big concern that hinders<br />

the effective protection not only of the biodiversity of<br />

the Sahamalaza Peninsula, but of Madagascar and its national<br />

parks system as a whole. Only 10 years ago, Madagascar was<br />

notorious for its environmental degradation and deforestation,<br />

but that began to change in 2003 when then President<br />

Marc Ravalomanana, working with international conservation<br />

organizations and local groups, set aside 10 % of the<br />

country’s surface area as national parks and started supporting<br />

ecotourism, which slowed deforestation and helped to<br />

safeguard biodiversity.After the political events in early 2009<br />

that saw the ousting of the President and the installation of a<br />

transitional government, the majority of donor funds, which<br />

provided half the government’s annual budget, have been<br />

withdrawn, leading to major funding gaps that have affected<br />

protected areas and their management. There currently is<br />

almost no money to employ park rangers or to implement<br />

other measures to protect the forests inside Madagascar’s<br />

national parks, and forest degradation is going on without<br />

noticeable resistance from the relevant authorities. Despite<br />

the political crisis that affects most of the social and environmental<br />

activities of numerous NGOs, AEECL is still carrying<br />

out its research activities and support to the villagers surrounding<br />

the Sahamalaza - Iles Radama National Park. Since<br />

the establishment of the protected area in 2007, AEECL has<br />

been conducting, besides its research programme, different<br />

projects that aim to reduce the excessive environmental exploitation<br />

inside and around the park.As the major activity of<br />

the local population surrounding the Sahamalaza Peninsula<br />

National Park is rice-growing,every year AEECL organizes a<br />

rice-growing training course and rice-growing competition,<br />

using modern techniques in order to increase yield per ha<br />

and to decrease the use of slash and burn agriculture.To stop<br />

the ongoing overexploitation of the environment, environmental<br />

education is another important part of AEECL´s<br />

work.As many villages in Sahamalaza are unable to pay teachers,<br />

AEECL subsidizes teachers’ salaries to ensure the primary<br />

education of the local children. Additionally, leaflets<br />

about the Sahamalaza biodiversity and its importance are<br />

distributed. They inform and educate villagers about the importance<br />

of lemurs and other species for their forest ecosystem.<br />

To minimise bush fires and to protect the forest against<br />

uncontrolled fires, AEECL organizes firebreak programs<br />

around the Ankarafa Forest, close to the research camp,<br />

where during three days, hundreds of local people remove<br />

the grasses on a 7m wide strip around the forest fragments.<br />

Furthermore, several reforestation campaigns have been<br />

conducted, where villagers, including many teachers and<br />

their pupils,have planted trees around their villages with the<br />

help of AEECL.<br />

Because of all the factors described here, the protection of<br />

Sahamalaza’s unique flora and fauna continues to be a major<br />

challenge that has to be faced by the local human population<br />

with the help of Madagascar National Parks and foreign partners.<br />

Two essential parts of AEECL’s efforts to help meeting<br />

this challenge are to stimulate further scientific study of<br />

endangered lemurs and other wildlife at its research station<br />

in the Ankarafa Forest, especially by Malagasy students, and<br />

to enable the local human population around the Sahamalaza<br />

- Iles Radama National Park to sustainably use their natural<br />

resources.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to thank Madagascar National Parks (MNP),<br />

especially the director of Sahamalaza - Iles Radama National<br />

Park, M. ISAIA Raymond, for their continuing collaboration.

Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010 Page 9<br />

Thank you also to the DGEF and CAFF/CORE for granting<br />

us research permits for our work in Sahamalaza,and to Prof.<br />

RABARIVOLA Clément for his ongoing help. Tantely Ralantoharijaona<br />

and Bronwen Daniel,along with all Ankarafa field<br />

guides, contributed substantially to fighting forest fires and<br />

other environmental threats in Ankarafa in 2009. MS was<br />

funded by Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation,<br />

AEECL, Conservation International Primate Action Fund,<br />

Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation, Mohamed bin Zayed<br />

Species Conservation Fund,International Primatological Society<br />

and Christian-Vogel-Fonds.<br />

References<br />

Birkinshaw, C.R. 2004. Priority areas for plant conservation.<br />

Ravintsara 2(1): 14-<strong>15</strong>.<br />

Ruperti, F. 2007. Population density and habitat preferences<br />

of the Sahamalaza sportive lemur (Lepilemur sahamalazensis)<br />

at the Ankarafa research site, NW Madagascar.<br />

Unpublished MSc thesis, Oxford Brookes University, UK.<br />

82 p.<br />

Ruperti,F.;Smith,J.;Ratovonasy,L.;Thorn,J.2008.Sahamalaza<br />

Conservation Action Plan (SCAP).Unpublished report to<br />

the Association Européenne pour l’Etude et la Conservation<br />

des Lémuriens (AEECL). 17 p.<br />

Schwitzer, C.; Randriatahina, G.H. 2009. AEECL: Update on<br />

activities. Lemur News 14: 11-12.<br />

Schwitzer, N.; Randriatahina, G.H.; Kaumanns, W.; Hoffmeister,<br />

D.; Schwitzer, C. 2007. Habitat utilization of blue-eyed<br />

black lemurs,Eulemur macaco flavifrons (Gray,1867),in primary<br />

and altered forest fragments.Primate Conservation<br />

22: 79-87.<br />

Schwitzer, C.; Schwitzer, N.; Randriatahina, G.H.; Rabarivola,<br />

C.; Kaumanns, W. 2006. "Programme Sahamalaza": New<br />

perspectives for the in situ and ex situ study and conservation<br />

of the blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur macaco flavifrons)<br />

in a fragmented habitat.Pp.135-149.In:C.Schwitzer;<br />

S.Brandt;O.Ramilijaona;M.Rakotomalala Razanahoera;D.<br />

Ackermand; T. Razakamanana; J. U. Ganzhorn (eds.). Proceedings<br />

of the German-Malagasy Research Cooperation<br />

in Life and Earth Sciences. Berlin: Concept Verlag.<br />

News and Announcements<br />

Madagascar conservationist wins international<br />

environmental prize<br />

Mr Rabary Desiré has been awarded the 2010 Seacology<br />

Prize (www.seacology.org/prize/index.htm) for his his tireless<br />

efforts to further forest conservation in northeastern Madagascar.Mr<br />

Desiré will receive the US$10,000 Prize on October<br />

7, 2010 at a ceremony in Berkeley, California.<br />

Rabary Desiré is recognized by many as a major conservation<br />

leader in northeastern Madagascar, and is a highlysought-after<br />

research and eco-tourism guide. With the money<br />

he makes from guiding,he buys forested land in order to<br />

protect it.Years of work have finally culminated in the establishment<br />

of his own small private nature reserve called<br />

Antanetiambo (antanetiambo.marojejy.com/Intro_e.htm),<br />

which means "on the high hill". It is perhaps the only reserve<br />

in northern Madagascar that has been entirely created from<br />

start to finish by a single local resident.<br />

According to Mr Desiré, "I am very happy to receive this<br />

award and I feel very lucky for myself and Madagascar. After<br />

many years of hard work and political instability,finally we are<br />

having some local conservation success. I plan to use these<br />

funds for such projects as reforestation, developing tourist<br />

Fig. 1: Rabary Desiré next to the sign for the Antanetiambo<br />

Nature Reserve he created.<br />

infrastructure and purchasing the land around Antanetiambo<br />

Nature Reserve to increase the size of the reserve and the<br />

amount of protected land in this region. This award will help<br />

preserve the precious biodiversity and high endemism of<br />

Madagascar,as well as fight the ongoing battle against massive<br />

deforestation and possible extinction of many beloved species...<br />

Thanks Seacology for giving me this prize. The whole<br />

region will never forget it."<br />

Read the full press release:<br />

www.seacology.org/news/display.cfm?id=4238<br />

Célébration du quinzième anniversaire<br />

du GERP (1994-2009)<br />

Jonah Ratsimbazafy*, Rose Marie Randrianarison,<br />

Muriel Nirina Maeder<br />

GERP, 34, Cité des Professeurs, Antananarivo 101,<br />

Madagascar<br />

*Corresponding author: gerp@wanadoo.mg<br />

Quinze ans se sont écoulés depuis la création, en 1994, de la<br />

Société de Primatologie malgache ou Groupe d’Etude et de<br />

Recherche sur les Primates de Madagascar (GERP). Elle fut<br />

fondée par dix Primatologues dont le Professeur Berthe<br />

Rakotosamimanana qui occupait à la fois le poste de Secrétaire<br />

Général du GERP et le Co-éditeur de la revue Lemur<br />

News jusqu’à sa disparition en 2005. De son vivant, elle<br />

désirait ardemment passer le flambeau au Docteur Jonah<br />

Ratsimbazafy pour le poste de Secrétaire Général du GERP<br />

qui, en 2006, a été mandaté à l’unanimité par les membres<br />

nationaux et internationaux du GERP au titre de Leader du<br />

GERP.<br />

L’Association compte aujourd’hui 169 membres et 20 d’entre<br />

eux sont de nationalité étrangère. La multidisciplinarité<br />

des membres du groupe (Primatologues, Anthropologues,<br />

Paléontologues, Ornithologues, Herpétologues, Spécialistes<br />

de Micromammifères et Mammifères, Parasitologistes, Botanistes,<br />

Géographes, Vétérinaires, Agro-forestiers, Biochimis-

Page 10 Lemur News <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>15</strong>, 2010<br />

tes, Dessinateur, Financiers) apporte une importante potentialité<br />

dans l’accomplissement de la mission du GERP: transférer<br />

les compétences nécessaires à la préservation de la<br />

biodiversité pour les générations futures. Par ailleurs, les actions<br />

du GERP comprennent également la formation des<br />

pépinières de Primatologues, la mise en œuvre du plan de<br />

conservation des lémuriens, la contribution à l’amélioration<br />

des activités génératrices de revenu des communautés de<br />

base liées à la conservation,sans oublier l’éducation environnementale<br />

de la population cible.<br />

En 2007,l’attribution par le GERP du nom de Microcebus macarthurii<br />

à une nouvelle espèce découverte dans la forêt de<br />

Makira représentait un témoignage de reconnaissance au<br />

dévouement de la Fondation MacArthur. De plus, le GERP a<br />

depuis 2008 officiellement été mandaté par le MEFT/DGEF/<br />

DSAP comme Gestionnaire de la forêt de Maromizaha,pour<br />

que cette dernière devienne une Nouvelle Aire Protégée<br />

(NAP).Plus récemment encore,en février 2010,le prix "lifetime"<br />