Fisheries in the Southern Border Zone of Takamanda - Impact ...

Fisheries in the Southern Border Zone of Takamanda - Impact ...

Fisheries in the Southern Border Zone of Takamanda - Impact ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Smithsonian Institution<br />

SI/MAB Biodiversity Program<br />

SI/MAB Series #8<br />

© 2003 by SI/MAB Biodiversity Program<br />

All rights reserved<br />

ISBN # 1-893912-12-4<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Congress<br />

Catalog Control Number: 2003106957<br />

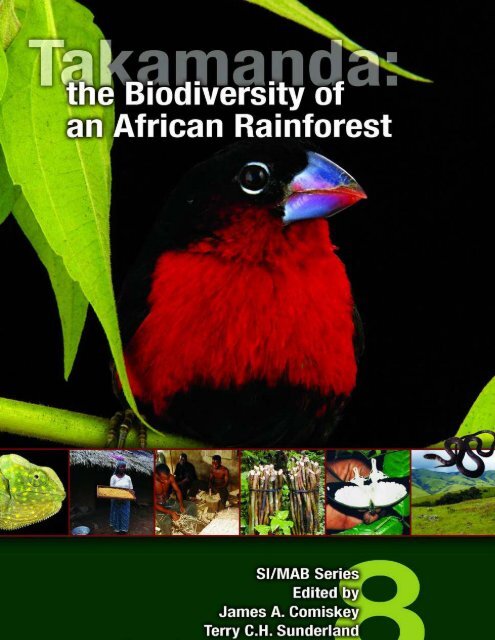

Cover design and <strong>in</strong>serts: Velvette De Laney<br />

Cover photographs: Western Bluebill, Spermophaga haemat<strong>in</strong>a (Carlton Ward, Jr). Views, animals, communities and<br />

research <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon (Sunderland, Dallmeier, Ward Jr, Lucas).<br />

Op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SI/MAB Series are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors and do not necessarily reflect those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Smithsonian Institution or partner organizations.<br />

Suggested citation: Comiskey, J. A., T. C. H. Sunderland, and J. L. Sunderland-Groves, eds. 2003. <strong>Takamanda</strong>: <strong>the</strong><br />

Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an African Ra<strong>in</strong>forest, SI/MAB Series #8. Smithsonian Institution, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>of</strong> America by Charter Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, Alexandria, VA, on recycled paper. This publication was<br />

made possible through <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups.

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Recent SI/MAB Publications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii<br />

Contributors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iv<br />

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi<br />

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . viii<br />

1. <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves, Terry C. H. Sunderland, James A. Comiskey<br />

Julius S. O. Ayeni, and Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1<br />

2. Adaptive Management: A Framework for Biodiversity Conservation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve,<br />

Cameroon<br />

James A. Comiskey and Francisco Dallmeier. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<br />

3. Vegetation Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Terry C.H. Sunderland, James A. Comiskey, Simon Besong, Hyac<strong>in</strong>th Mboh,<br />

John Fonwebon, and Mercy Abwe Dione. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

4. Butterfly Fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Ebwekoh Monya O’ Kah . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55<br />

5. Biodiversity Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Odonate Fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Graham S. Vick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73<br />

6. Reptiles <strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Mat<strong>the</strong>w LeBreton, Laurent Chirio, and Désiré Foguekem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83<br />

7. The Birds <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Marc Languy and Francis Njie Motombe. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

8. Large Mammals <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves and Fiona Maisels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111<br />

9 Surveys <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cross River Gorilla and Chimpanzee Populations <strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest<br />

Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves, Fiona Maisels, and Albert Ek<strong>in</strong>de . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

ii<br />

10. <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Border</strong> <strong>Zone</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli, Tim Du Feu and Julius S.O. Ayeni . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141<br />

11. Distribution, Utilization, and Susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Non-Timber Forest Products from <strong>Takamanda</strong><br />

Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Terry C.H. Sunderland, Simon Besong, and Julius S. O. Ayeni . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155<br />

12. Landcover Change <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon: 1986 - 2000<br />

Dan Slayback . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173<br />

13. Future Conservation and Management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Terry C. H. Sunderland, Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves, James A. Comiskey,<br />

Julius S. O. Ayeni, and Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181

Recent SI/MAB Publications<br />

Dallmeier, F., A. Alonso, and P. Campbell, eds. 2002. Special Issue: Biodiversity Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment for<br />

Adaptive Management: L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Conservation and Development. Environmental Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment 76.<br />

Dallmeier, F., A. Alonso and D. Kloepfer. 2002. Adventures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest: Discover<strong>in</strong>g Biodiversity. Smithsonian<br />

Institution/Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, A., F. Dallmeier, and P. Campbell, eds. 2001. Urubamba: The Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> a Peruvian Ra<strong>in</strong>forest, SI/MAB<br />

Series #7. Smithsonian Institution, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, L. E., A. Alonso, T. S. Schulenberg, and F. Dallmeier. 2001. Biological and social assessments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera<br />

de Vilcabamba, Peru. RAP Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers 12 and SI/MAB Series #6. Conservation International. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,<br />

DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, A., F. Dallmeier, E. Granek, and P. Raven. 2001. Biodiversity: Connect<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> Tapestry <strong>of</strong> Life.<br />

Smithsonian Institution/Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity Program and President’s Committee <strong>of</strong><br />

Advisors on Science and Technology. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, A. and F. Dallmeier. 2000. Work<strong>in</strong>g for Biodiversity. Smithsonian Institution/Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

Biodiversity Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Comiskey, J. A., F. Dallmeier, and A. Alonso. 2000. Framework for assessment and monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> biodiversity. In:<br />

Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity (S. Lev<strong>in</strong>, ed.). Volume 3, 63-73pp. Academic Press. San Diego, CA.<br />

Ojasti, J. 2000. Manejo de Fauna Silvestre Neotropical. Edited by F. Dallmeier. SI/MAB Series #5. Smithsonian<br />

Institution/MAB Biodiversity Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Herrera-MacBryde, O., F. Dallmeier, B. MacBryde, J.A. Comiskey and C. Miranda, eds. 2000. Biodiversidad,<br />

Conservación y Manejo en la Región de la Reserva de la Biosfera Estación Biológical del Beni, Bolivia /<br />

Biodiversity, Conservation and Management <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Region <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Beni Biological Station Biosphere Reserve,<br />

Bolvia, SI/MAB Series #4. Smithsonian Institution/MAB Biodiversity Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, A. and F. Dallmeier, eds. 1999. Biodiversity Assessment and Monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lower Urubamba Region,<br />

Peru: Pagoreni Well Site Assessment and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, SI/MAB Series #3. Smithsonian Institution/MAB Biodiversity<br />

Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Alonso, A. and F. Dallmeier, eds. 1998. Biodiversity Assessment and Monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lower Urubamba Region,<br />

Peru: Cashiriari-3 Well Site and <strong>the</strong> Camisea and Urubamba Rivers, SI/MAB Series #2. Smithsonian<br />

Institution/MAB Biodiversity Program, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, USA.<br />

Dallmeier, F. and J. Comiskey, eds. 1998. Forest Biodiversity <strong>in</strong> North, Central and South America, and <strong>the</strong> Caribbean:<br />

Research and Monitor<strong>in</strong>g, Man and <strong>the</strong> Biosphere Series, Vol. 21. Par<strong>the</strong>non Press, Carnforth, Lancashire, UK.<br />

Dallmeier, F. and J. Comiskey, eds. 1998. Forest Biodiversity Research, Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Model<strong>in</strong>g: Conceptual<br />

Background and Old World Case Studies, Man and <strong>the</strong> Biosphere Series, Vol. 20. Par<strong>the</strong>non Press, Carnforth,<br />

Lancashire, UK.

Mercy Abwe Dione<br />

Dept. <strong>of</strong> Biology, University <strong>of</strong> Buea<br />

Buea, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Julius S. O. Ayeni<br />

Project for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Forests around Akwaya<br />

(PROFA)<br />

GTZ-MINEF<br />

Mamfe, Manyu Division, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce,<br />

Cameroon<br />

Simon Besong<br />

Botanical Researcher<br />

Project for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Forests around Akwaya<br />

(PROFA),<br />

GTZ-MINEF<br />

Mamfe, Manyu Division, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce,<br />

Cameroon<br />

Laurent Chirio<br />

14 Rue des Roses<br />

06130 Grasse<br />

France<br />

James A. Comiskey<br />

Smithsonian Institution<br />

SI/MAB Program<br />

Conservation and Research Center, NZP<br />

1100 Jefferson Dr., SW, Suite 3123<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20560-0705<br />

USA<br />

Francisco Dallmeier<br />

Smithsonian Institution<br />

SI/MAB Program<br />

Conservation and Research Center, NZP<br />

1100 Jefferson Dr., SW, Suite 3123<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20560-0705<br />

USA<br />

Contributors<br />

Albert Ek<strong>in</strong>de<br />

Cross River Gorilla Research Project (Cameroon)<br />

Wildlife Conservation Society<br />

C/O Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

PO Box 437<br />

Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Tim du Feu<br />

Jersey JE3 6AW<br />

Channel Isles<br />

UK<br />

Désiré Foguekem<br />

Cameroon Biodiversity Conservation Society<br />

PB 3055 Messa Yaounde<br />

Cameroon<br />

John Fonwebon<br />

Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

PO Box 437<br />

Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Marc Languy<br />

BirdLife International Cameroon Programme<br />

Currently:<br />

Albert<strong>in</strong>e Rift Ecoregion Coord<strong>in</strong>ator<br />

WWF-Eastern Africa Regional Programme Office<br />

BP 62440<br />

00200 Nairobi<br />

Kenya<br />

Fiona Maisels<br />

Wildlife Conservation Society<br />

International Programmes<br />

2300 Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Boulevard<br />

Bronx, NY 10460, USA<br />

and<br />

I.C.A.P.B., Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh University, U.K.

Mat<strong>the</strong>w LeBreton<br />

Cameroon Biodiversity Conservation Society<br />

PB 3055 Messa Yaounde<br />

Cameroon<br />

Hyac<strong>in</strong>th Mboh<br />

Cross River Gorilla Research Project (Cameroon)<br />

Wildlife Conservation Society<br />

C/O Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

PO Box 437<br />

Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli<br />

Project for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Forests around Akwaya<br />

(PROFA),<br />

GTZ-MINEF<br />

Mamfe, Manyu Division, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Ebwekoh Monya O' Kah<br />

Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

P.O Box 437<br />

Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Francis Njie Motombe<br />

Club Ornithologique du Cameroun<br />

PO Box 437, Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Dan Slayback<br />

Science Systems and Applications, Inc.<br />

Biospheric Sciences Branch, Code 923<br />

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center<br />

Greenbelt, MD 20771<br />

USA<br />

Terry C.H. Sunderland<br />

SI/MAB Biodiversity Program<br />

Smithsonian Institution<br />

and<br />

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew<br />

C/O Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

PO Box 437, Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Biological Sciences<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Sussex, UK<br />

and<br />

Cross River Gorilla Research Project (Cameroon),<br />

Wildlife Conservation Society<br />

C/O Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

PO Box 437,<br />

Limbe, Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

Cameroon<br />

Graham S. Vick<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Biology<br />

Imperial College, University <strong>of</strong> London<br />

Silwood Park, Ascot, Berks, SL5 7PY<br />

United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

v

The Smithsonian Institution has long been aware <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> southwestern Cameroon to global<br />

biodiversity and as a storehouse <strong>of</strong> resources with<br />

potentially significant value to humank<strong>in</strong>d. In <strong>the</strong> 1990s,<br />

scientists from <strong>the</strong> Division <strong>of</strong> Experimental Therapeutics<br />

at Walter Reed Army Institute <strong>of</strong> Research and <strong>the</strong><br />

Bioresources Development and Conservation Programme<br />

approached <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian with an <strong>of</strong>fer to jo<strong>in</strong> research<br />

<strong>in</strong> Nigeria and Cameroon aimed at us<strong>in</strong>g development <strong>of</strong><br />

pharmaceutical drugs to catalyze conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity. Out <strong>of</strong> those <strong>in</strong>itial discussions, <strong>the</strong><br />

International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups for West<br />

Africa was formed, based on <strong>the</strong> belief that <strong>the</strong> discovery<br />

and development <strong>of</strong> pharmaceuticals and o<strong>the</strong>r useful<br />

products from natural resources can, under appropriate<br />

circumstances, promote susta<strong>in</strong>ed economic growth <strong>in</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries and conserve <strong>the</strong> biological<br />

resources from which <strong>the</strong> products are derived. Priority<br />

objectives were to establish and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>of</strong><br />

species used <strong>in</strong> traditional medic<strong>in</strong>e; collect, chemically<br />

analyze, and test plant samples for potential medic<strong>in</strong>al<br />

development; identify key compounds for <strong>the</strong> treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> diseases such as malaria, HIV-AIDS, cancer, cystic<br />

fibrosis, and leischmaniasis; establish and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

research plots for long-term assessment <strong>of</strong> ecological<br />

dynamics <strong>in</strong> ra<strong>in</strong>forests; conduct economic value<br />

assessments <strong>of</strong> major species <strong>in</strong> host countries; and tra<strong>in</strong><br />

Nigerian and Cameroonian scientists and technicians <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> various aspects <strong>of</strong> plant research and ecology.<br />

For nearly ten years, <strong>the</strong> Smithonsian and<br />

Bioresources Development and Conservation Programme<br />

have coord<strong>in</strong>ated biodiversity conservation and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

for <strong>the</strong> International Cooperative Biodiversity Group. The<br />

Smithsonian has focused on establish<strong>in</strong>g an extensive<br />

network <strong>of</strong> biodiversity monitor<strong>in</strong>g plots <strong>in</strong> Nigeria and<br />

Cameroon and an <strong>in</strong>tensively researched forest dynamics<br />

plot <strong>in</strong> Korup National Park, Cameroon. The goal is<br />

Preface<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> processes that ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

biodiversity <strong>in</strong> Central and West African forests.<br />

Smithsonian has conducted detailed forest<br />

biodiversity assessments <strong>in</strong> collaboration with numerous<br />

partner organizations to provide basel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

needed to develop regional conservation strategies. We<br />

have also provided pr<strong>of</strong>essional tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> plant<br />

taxonomy, collection techniques, biodiversity monitor<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

data analysis, and environmental leadership for <strong>in</strong>-country<br />

students and natural resource technicians. Our o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

efforts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region <strong>in</strong>clude support <strong>of</strong> herbariums,<br />

computer facilities, and o<strong>the</strong>r components <strong>of</strong> local<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure and capacity. Partners who have jo<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> drug screen<strong>in</strong>g and resource development aspect <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> program <strong>in</strong>clude Walter Reed Army Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Research, University <strong>of</strong> Buea (Cameroon), University <strong>of</strong><br />

Dschang (Cameroon), University <strong>of</strong> Jos (Nigeria), Pace<br />

University (New York), Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Research Institute<br />

(Alabama), <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Utah, <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong><br />

Miami, and Florida State University.<br />

Fund<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> overall program stems from <strong>the</strong><br />

International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups Program,<br />

a consortium <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health, <strong>the</strong><br />

Biological Sciences Directorate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Science<br />

Foundation, and <strong>the</strong> Foreign Agriculture Service <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture. Cooperat<strong>in</strong>g National<br />

Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health agencies <strong>in</strong>clude Fogarty International<br />

Center, National Cancer Institute, National Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and<br />

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.<br />

The <strong>Takamanda</strong> Project was a collaborative, multi<strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

effort to provide an <strong>in</strong>itial series <strong>of</strong><br />

assessments for selected taxa <strong>in</strong> this region <strong>of</strong><br />

southwestern Cameroon and elicit <strong>the</strong> data needed to form

a basel<strong>in</strong>e for future research and conservation.<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve was relatively unexplored<br />

until this project. Increas<strong>in</strong>g threats to <strong>the</strong> long-term<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> both flora and fauna <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve prompted<br />

<strong>the</strong> authors and <strong>the</strong>ir respective affiliations to conduct <strong>the</strong><br />

biodiversity assessments that we report on <strong>in</strong> this book..<br />

An additional outcome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Project<br />

was formal tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g through courses conducted by <strong>the</strong><br />

Smithsonian Institution <strong>in</strong> collaboration with <strong>the</strong><br />

Bioresources Development and Conservation Program,<br />

<strong>the</strong> International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups,<br />

WWF Cameroon, <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Conservation Society and<br />

<strong>the</strong> US Agency for International Development’s Central<br />

African Regional Program for <strong>the</strong> Environment.<br />

vii<br />

Cont<strong>in</strong>ued capacity build<strong>in</strong>g was conducted throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> different field activities.<br />

As an outgrowth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> International Cooperative<br />

Biodiversity Groups Program, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Project is<br />

based on <strong>the</strong> premise that <strong>the</strong> discovery and development<br />

<strong>of</strong> products (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pharmaceuticals) from natural<br />

resources may well promote susta<strong>in</strong>able use <strong>of</strong> those<br />

resources and contribute to <strong>the</strong> economic and social wellbe<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> local communities.<br />

Francisco Dallmeier<br />

National Zoological Park<br />

Smithsonian Institution

The editors <strong>of</strong> this publication extend <strong>the</strong>ir gratitude to <strong>the</strong><br />

many people who assisted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> preparation <strong>of</strong> this book,<br />

particularly those who worked <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> field and whose<br />

valuable contributions are reflected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> chapters<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Dan Slayback <strong>of</strong> NASA(formerly <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Peace Corps<br />

<strong>in</strong> Cameroon) was key to <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> maps, far<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> call <strong>of</strong> duty.<br />

We thank <strong>the</strong> many technicians who worked on this<br />

project, especially "tree spotters" Anacletus Koufani <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> National Herbarium and Bioresources Development<br />

Conservation Programme-Cameroon, Maurice Elad <strong>of</strong><br />

Tropenbos, and Aron Bibout and Paul Owono Nguille <strong>of</strong><br />

ONADEF. With <strong>the</strong>ir expertise, much <strong>of</strong> this work and<br />

that which preceded it was <strong>of</strong> great value.<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli and Julius Ayeni <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GTZ-funded<br />

project PROFA were <strong>in</strong>strumental <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

multi-taxa approach employed throughout <strong>the</strong> study and<br />

were <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> much logistical, f<strong>in</strong>ancial, and moral<br />

support. Thanks also to Raphael Ebot, former Division<br />

Chief <strong>of</strong> Forestry for Manyu Division, for his unst<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study and to <strong>the</strong> MINEF staff <strong>in</strong> Mamfe.<br />

The M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Scientific and Technical Research,<br />

most notably Mr. John Che, deserves our gratitude for<br />

facilitat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> procurement <strong>of</strong> relevant research and<br />

export permits.<br />

We are most pleased to recognize Dr. Nouhou Ndam<br />

and <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> Limbe Botanical and Zoological Gardens<br />

and its marvelous herbarium for giv<strong>in</strong>g us an <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

home. We hope that our work has succeeded <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> excellent research facilities <strong>of</strong> this center.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

We appreciate <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian MAB<br />

Program, most assuredly Tatiana Pacheco for her<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrative skills. Thanks also to Patricia Ojeda for her<br />

thorough work <strong>in</strong> verify<strong>in</strong>g species taxonomic<br />

nomenclatures, Deanne Kloepfer for review<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

edit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> chapters, and Bryan Hayum for his assistance<br />

<strong>in</strong> formatt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al publication, while Patrick<br />

Campbell, Alfonso Alonso, Francisco Dallmeier, Roger<br />

Soles, Adam Wilcox, Sandra Rub<strong>in</strong>i, and Geri Philpott<br />

provided additional reviews. Carlton Ward Jr. and authors<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chapters are responsible for photographs, while<br />

Velvette De Laney expertly executed <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sert and cover<br />

designs.<br />

Fund<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> vegetation assessments, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

courses, and current publication was provided by <strong>the</strong><br />

International Cooperative Biodiversity Group for West<br />

and Central Africa. We thank <strong>the</strong> Bioresources<br />

Development and Conservation Programme, and<br />

especially Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Maurice Iwu, for cont<strong>in</strong>ued support<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institution's work <strong>in</strong> Cameroon and<br />

Nigeria. Additional funds for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g were provided by<br />

USAID’s Central African Regional Program for <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment.<br />

Last but not least, we extend our heartfelt<br />

appreciation to all Chiefs, Traditional Council Members,<br />

Youth Leaders, and community representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve and its environs for <strong>the</strong>ir help,<br />

hospitality, and significant contributions to this<br />

publication. Mart<strong>in</strong> Ashu, Zach Abang, Mart<strong>in</strong> Tiko, Yisa<br />

Emmanuel, Jasper Obi, Denis Agbor, Esalo Godw<strong>in</strong>, and<br />

Jackson Aveh deserve special mention, although many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs showed dedication <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g this publication<br />

possible. As <strong>the</strong> say<strong>in</strong>g goes, "It takes two hands to tie a<br />

bundle!"

1 The region<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e L. Sunderland-Groves, Terry C. H. Sunderland,<br />

James A. Comiskey, Julius S. O. Ayeni, and Mar<strong>in</strong>a Mdaihli<br />

The Republic <strong>of</strong> Cameroon extends from 2° N to 13° N<br />

latitude and between 8° 25' E and 16° 20' W longitude.<br />

The country has a total area <strong>of</strong> 475,440 km² and is<br />

bordered by Chad, Nigeria, Congo, Gabon, Equatorial<br />

Gu<strong>in</strong>ea and a 350-km stretch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atlantic Ocean<br />

coastl<strong>in</strong>e. <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve (TFR) is located <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> Cameroon. The Reserve is<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gu<strong>in</strong>eo-Congolean forest, which<br />

encompasses approximately 2.8 million km 2 mostly<br />

below 600 m, except where Precambrian highlands such<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Jos Plateau <strong>of</strong> Nigeria and <strong>the</strong> Cameroon<br />

Highlands rise above 1000m (Lawson 1996). The<br />

highest po<strong>in</strong>t is Mount Cameroon at 4,079 m.<br />

Ra<strong>in</strong>fall <strong>in</strong> this vast forest varies from 1500 to more<br />

than 10,000 mm per year, giv<strong>in</strong>g rise to a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

vegetation floristic regions (White 1983). The region<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>s 84% <strong>of</strong> known African primates, 68% <strong>of</strong> known<br />

African passer<strong>in</strong>e birds, and 66% <strong>of</strong> known African<br />

butterflies (Groombridge and Jenk<strong>in</strong>s 2000). For this<br />

reason, <strong>the</strong> Gu<strong>in</strong>eo-Congolian ra<strong>in</strong>forest is an important<br />

focal po<strong>in</strong>t for conservation efforts <strong>in</strong> Africa.<br />

The Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce and adjacent portions <strong>of</strong><br />

sou<strong>the</strong>astern Nigeria are rich <strong>in</strong> biodiversity.<br />

Floristically, this area is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hygrophylous Coastal<br />

Evergreen Ra<strong>in</strong>forest, which occurs along <strong>the</strong> Gulf <strong>of</strong><br />

Biafra. This vegetation sub-unit is associated with high<br />

ra<strong>in</strong>fall levels (White 1983) and is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cross-<br />

Sanaga-Bioko Coastal Forest ecoregion, an area <strong>of</strong><br />

52,000 km 2 (Olson et al. 2001, World Wildlife Fund<br />

2001). The ecoregion is considered an important center<br />

<strong>of</strong> plant diversity because <strong>of</strong> its probable isolation dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pleistocene (Davis et al. 1994).<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Protected areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region <strong>in</strong>clude Cross River<br />

National Park <strong>in</strong> Nigeria and Korup National Park <strong>in</strong><br />

Cameroon, as well as an extensive network <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

reserves such as Ejagham and <strong>Takamanda</strong> (Figure 1).<br />

2 <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve (05º59’-06º21’N: 09º11-<br />

09º30’E), cover<strong>in</strong>g 67,599 ha, is situated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost corner <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce,<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extensive Cross River Valley. The<br />

Reserve stretches along <strong>the</strong> eastern border <strong>of</strong> Nigeria<br />

(Figure 2), which forms <strong>the</strong> north and northwest<br />

boundaries <strong>of</strong> TFR (Gartlan 1989).<br />

Created by decree <strong>in</strong> 1934, <strong>the</strong> area was first gazetted<br />

as part <strong>of</strong> a network <strong>of</strong> forest reserves (production<br />

forests) by <strong>the</strong> British colonial adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>in</strong> what<br />

was <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> British Cameroons. Ak<strong>in</strong> with forest policy<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> British Empire, TFR was <strong>in</strong>itially<br />

established to protect watersheds and restrict <strong>the</strong><br />

expansion <strong>of</strong> agricultural, but more importantly to<br />

conserve areas for future logg<strong>in</strong>g. As with all gazetted<br />

areas <strong>in</strong> Cameroon, <strong>the</strong> Reserve is managed on <strong>the</strong><br />

national level by <strong>the</strong> Cameroon Government Forestry<br />

Department’s M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Environment and Forests<br />

(MINEF) through <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry’s Manyu Division Office<br />

<strong>in</strong> Mamfe. The Manyu <strong>of</strong>fice is responsible to <strong>the</strong><br />

Prov<strong>in</strong>cial Delegate <strong>in</strong> Buea.<br />

3 Geomorphology and dra<strong>in</strong>age<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowland forest area <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn and<br />

central part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve lies between 100 and 400 m.<br />

The terra<strong>in</strong> is roll<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowland areas, but rises<br />

sharply to an altitude <strong>of</strong> 1,500 m <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Reserve, where slopes are extremely steep. Small<br />

SI/MAB Series #8, 2003, Pages 1 to 8

2 Sunderland-Groves et al.<br />

Figure 1. Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> Cameroon and <strong>the</strong> associated protected areas.<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong>: <strong>the</strong> Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an African Ra<strong>in</strong>forest<br />

Protected areas<br />

(NP=National Park; FR=Forest<br />

Reserve; WS=Wildlife Sanctuary;<br />

CF=Community Forest)<br />

1 Korup NP<br />

2 Cross River NP,<br />

Oban Division<br />

3 Cross River NP,<br />

Okwangwo Division<br />

4 Afi Mounta<strong>in</strong> WS<br />

5 Afi River FR<br />

6 Bakala FR<br />

7 Bambuko FR<br />

8 Banyang Mbo WS<br />

9 Cross River North FR<br />

10 Cross River South FR<br />

11 Dibombe Mabobe FR<br />

12 Ejagham FR<br />

13 Ek<strong>in</strong>ta FR<br />

14 Mbe CF<br />

15 Mbulu Hills CF<br />

16 Meme River FR<br />

17 Mokoko River FR<br />

18 Mone River FR<br />

19 Mouyouka Komp<strong>in</strong>a FR<br />

20 Nta Ali FR<br />

21 Rumpi Hills FR<br />

22 S Bakundu FR<br />

23 Stubbs Creek FR<br />

24 Ukpon River FR

3<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve<br />

SI/MAB Series #8, 2003<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

77<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

77<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

7<br />

w——<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

y2@w—˜A<br />

e—<br />

e<br />

e<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w<br />

y˜2P<br />

y˜2Q<br />

„———— „—<br />

w˜<br />

w˜<br />

e——<br />

w—<br />

x—<br />

y—˜<br />

e—<br />

f——<br />

„—<br />

w<br />

w——<br />

i˜<br />

„——<br />

f—<br />

w<br />

p<br />

‚<br />

6w—2PI2<br />

g2‚<br />

x——2€—<br />

y—2h<br />

g2‚2ƒ—<br />

ƒ2€<br />

gewi‚yyx<br />

„————<br />

p<br />

‚<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

u2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

y˜2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

f—2I<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

…˜<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

u—<br />

THH9<br />

THH9<br />

TS9<br />

TS9<br />

TIH9<br />

TIH9<br />

TIS9<br />

TIS9<br />

TPH9<br />

TPH9<br />

WIH9<br />

WIH9<br />

WIS9<br />

WIS9<br />

WPH9<br />

WPH9<br />

WPS9<br />

WPS9<br />

WQH9<br />

WQH9<br />

IXPSHHHH<br />

H S IH<br />

u<br />

I<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

f—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

w—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜—<br />

x˜— y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P<br />

y2P y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

y2I<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

f———2I8P<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

„<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

w<br />

xsqi‚se<br />

Figure 2. <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve and nearby villages.

4 Sunderland-Groves et al.<br />

Ra<strong>in</strong>fall (mm)<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

Humidity<br />

Ra<strong>in</strong>fall<br />

Temperature<br />

JAN<br />

FEB<br />

MARCH<br />

APRIL<br />

MAY<br />

JUNE<br />

JULY<br />

AUG<br />

SEPT<br />

hills, up to 725 m <strong>in</strong> elevation, lie to <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Obonyi villages along <strong>the</strong> border with Nigeria. The hills<br />

separat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> villages <strong>of</strong> Kekpane and Basho are similar<br />

<strong>in</strong> elevation, ris<strong>in</strong>g to between 600 and 700 m.<br />

A basement complex <strong>of</strong> granite, gneisses, schist, and<br />

quartzites underlies <strong>the</strong> region, giv<strong>in</strong>g to shallow<br />

sedimentary soils (ENPLAN 1974). Mar<strong>in</strong>e sediment<br />

deposition occurred dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Precambrian, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

ferrite derived from crystall<strong>in</strong>e rock and large areas <strong>of</strong><br />

alluvial soil toward <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve.<br />

The Cross River and its numerous headwater<br />

tributaries form <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> water system <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region. The<br />

general direction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>age pattern is from north to<br />

south, with two major rivers, <strong>the</strong> Makone and Magbe,<br />

flow<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> Reserve. (The Magbe is called <strong>the</strong><br />

Oyi on <strong>the</strong> Nigerian side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> border.) The Makone<br />

dra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> Matene Highlands and runs southwest through<br />

<strong>the</strong> Reserve to meet <strong>the</strong> Munaya River. The Magbe flows<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong>: <strong>the</strong> Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an African Ra<strong>in</strong>forest<br />

OCT<br />

NOV<br />

DEC<br />

Figure 3. Climatic data for Besong-Abang to <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

100<br />

Humidity (%)<br />

from Matene through Nigeria and curves back <strong>in</strong>to<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong>; it represents a portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve’s<br />

western boundary and eventually dra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> Mamfe<br />

River.<br />

4 Climate and temperature<br />

The <strong>Takamanda</strong> area lacks accurate climatological data,<br />

which undoubtedly vary due to <strong>the</strong> elevational gradient<br />

that occurs with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve. In general, <strong>the</strong> region has<br />

two dist<strong>in</strong>ct seasons with most ra<strong>in</strong>fall occurr<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

April to November, peak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> July and August with a<br />

second peak <strong>in</strong> September (Figure 3). The total annual<br />

ra<strong>in</strong>fall is probably similar to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nigerian side <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> border <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Okwangwo region—up to 4,500 mm<br />

per year (World Wildlife Fund 1990). From November to<br />

April, <strong>the</strong> climate is ma<strong>in</strong>ly dry; some months, usually<br />

January and February, may receive no ra<strong>in</strong> at all. The<br />

mean annual temperature is about 27º C. Normally, it is<br />

cooler <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ra<strong>in</strong>y season than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dry season.<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

30<br />

29<br />

28<br />

27<br />

26<br />

25<br />

Temperature (degrees centigrade)

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve<br />

5 Settlement and culture<br />

Three enclaved villages, Kekpane, Obonyi I, and Obonyi<br />

III, lie <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve. Five more villages are located<br />

along <strong>the</strong> Reserve’s boundary, and <strong>the</strong>re are additional<br />

outly<strong>in</strong>g villages. Letouzey (1985) estimated <strong>the</strong> human<br />

population <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> to be between 6 and 12<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals per km 2. A more recent survey calculated that<br />

<strong>the</strong> 43 villages with<strong>in</strong> and around TFR, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 12<br />

villages on <strong>the</strong> Nigerian side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> border, conta<strong>in</strong><br />

15,707 people (Schmidt-Soltau et al. 2001).<br />

The dom<strong>in</strong>ant tribe with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area is Anyang, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> spoken language is Denya. The majority <strong>of</strong><br />

villagers, especially those located close to <strong>the</strong> Nigerian<br />

border, also speak or understand <strong>the</strong> closely-related Boki<br />

language, which is spoken on <strong>the</strong> Nigerian side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

border. Because <strong>of</strong> ethnic ties, people <strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong><br />

communities appear to have long-stand<strong>in</strong>g aff<strong>in</strong>ity with<br />

nearby Nigerian villagers.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g gazettement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve, local<br />

poplulations were granted traditional rights to use <strong>the</strong><br />

forest for <strong>the</strong>ir subsistence-based livelihoods. They also<br />

have legal right <strong>of</strong> passage through TFR, and <strong>the</strong>ma<strong>in</strong><br />

travel route is <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> a strong cross-border trad<strong>in</strong>g<br />

pattern. Agriculture, hunt<strong>in</strong>g, fish<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>the</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> non-timber forest products are widespread throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> Reserve (Mdahli et al. this volume, Sunderland et al.<br />

this volume). The ma<strong>in</strong> agricultural activities are<br />

subsistence farm<strong>in</strong>g for maize, planta<strong>in</strong>, banana, yams,<br />

and cassava. Cultivation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se annual crops <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

extends for some distance from <strong>the</strong> villages and has<br />

resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> virtually all <strong>the</strong> trees <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

immediate vic<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> settlements. Fur<strong>the</strong>r from <strong>the</strong><br />

villages, less extensive cultivation occurs, notably for oil<br />

palm, which is a major export from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> area.<br />

In anticipation <strong>of</strong> improved road access, cash crops—<br />

primarily cocoa and c<strong>of</strong>fee—have recently been<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced to <strong>the</strong> area.<br />

6 Flora and fauna<br />

Despite identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area as a priority for<br />

conservation (Gartlan 1989), biodiversity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> region was not well known until relatively<br />

recently. Early expeditions concentrated on large<br />

mammals, particularly gorillas (Sanderson 1940, March<br />

1957, Critchley 1968 Struhsaker, 1967, Thomas 1988,<br />

Sunderland-Groves et al. this volume). A more<br />

comprehensive study <strong>of</strong> TFR provides significantly more<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>the</strong> unique fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area (Groves and<br />

Maisels 1999, Groves 2002). It is now known that <strong>the</strong><br />

Reserve and <strong>the</strong> neighbor<strong>in</strong>g Okwangwo region <strong>in</strong><br />

Nigeria are important areas for many large mammals,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g an isolated population <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cross River<br />

gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) and <strong>the</strong> Nigerian<br />

chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes vellerosus), drill<br />

(Mandrillus leucophaeus), and Preuss’s Guenon<br />

(Cercopi<strong>the</strong>cus preussi). As well, <strong>the</strong> forest elephant<br />

(Loxodonta africana cyclotis) and buffalo (Syncerus<br />

caffer nanus) are local denizens.<br />

The wider biodiversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

vegetation, rema<strong>in</strong>ed unstudied, although it was<br />

speculated that because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> transition from lowland<br />

forest to montane savanna, <strong>the</strong> area would be particularly<br />

diverse for all biological taxa (Gartlan 1989). Letouzey<br />

(1985) and ONADEF (n.d.) mapped vegetation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Reserve and <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>g area as part <strong>of</strong> a national<br />

vegetation survey, provid<strong>in</strong>g two broad classification<br />

categories. Those studies were based on aerial<br />

photographs, however, ground-truth<strong>in</strong>g was not<br />

conducted. Subsequent work by Thomas (1988) and<br />

Etuge (1998) elicited more details with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wide<br />

categories <strong>of</strong> Letouzey and ONADEF. Still, until <strong>the</strong><br />

present work (see Sunderland et al. this volume),<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> TFR vegetation was <strong>in</strong>adequate.<br />

The present study provides for <strong>the</strong> first time a<br />

comprehensive overview <strong>of</strong> biodiversity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> area us<strong>in</strong>g analytical techniques developed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian Institution’s Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity Program (SI/MAB) with<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> an adaptive management approach for<br />

conduct<strong>in</strong>g assessments and monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> biodiversity.<br />

The work was modeled <strong>in</strong> part on SI/MAB projects <strong>in</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Peru and Gabon<br />

(Comiskey et al. 2000, Dallmeier et al. 2002).<br />

5<br />

SI/MAB Series #8, 2003

6 Sunderland-Groves et al.<br />

7 Conservation issues at<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past, <strong>Takamanda</strong> and <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>g area had<br />

largely been protected, more by default than by design,<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its <strong>in</strong>accessibility. However, recent human<br />

activities such as a logg<strong>in</strong>g concession granted <strong>in</strong> 1995<br />

outside <strong>the</strong> Reserve and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> a road from<br />

Mamfe to Akwaya (ongo<strong>in</strong>g) have enabled easier access<br />

to <strong>the</strong> area. Subsequently, <strong>the</strong> export <strong>of</strong> non-timber forest<br />

products, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g bushmeat, has <strong>in</strong>creased. With<br />

enhanced access, future logg<strong>in</strong>g and agricultural<br />

expansion, ei<strong>the</strong>r by <strong>the</strong> local population or through<br />

government concessions, have become major concerns.<br />

Without <strong>of</strong>ficial elevation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> protected status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Reserve, <strong>the</strong> forest is open to such activities.<br />

The major threat fac<strong>in</strong>g fauna <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve is<br />

hunt<strong>in</strong>g. Local people have had hunt<strong>in</strong>g rights, us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

traditional methods, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> area was gazetted <strong>in</strong> 1934,<br />

but <strong>the</strong>y were prohibited from us<strong>in</strong>g firearms. Thus, most<br />

hunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> bygone years was for subsistence. Today,<br />

smaller mammals such as duikers are killed through wire<br />

traps or snares, while larger mammals, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g apes,<br />

primates, elephants, and buffalos, are killed with rifles or<br />

locally made shotguns (“dane” guns). Almost all hunters<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area own a gun, and with few o<strong>the</strong>r options for<br />

alternative employment, hunt<strong>in</strong>g to provide bushmeat for<br />

trade (<strong>in</strong>come) is now common. Meat is consumed<br />

locally and exported to Mamfe and Bamenda <strong>in</strong><br />

Cameroon and across <strong>the</strong> border to Nigeria <strong>in</strong> large<br />

quantities. As a result, many mammal populations are<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g depleted at an alarm<strong>in</strong>g rate.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important conservation species <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> is <strong>the</strong> gorilla. Recently, scientists concluded<br />

that <strong>the</strong> gorillas from this region are geographically and<br />

morphologically dist<strong>in</strong>ct from o<strong>the</strong>r gorillas (Sarmiento<br />

and Oates 2000), and <strong>the</strong>y are now recognized as <strong>the</strong><br />

fourth gorilla sub–species—<strong>the</strong> Cross River gorilla—and<br />

classified as critically endangered (IUCN 2000). Groves<br />

et al. (this volume) estimated <strong>in</strong> 2002 that <strong>the</strong>re were<br />

approximately 180 Cross River gorillas rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

TFR and <strong>the</strong> adjacent forest areas <strong>of</strong> Mone Forest<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong>: <strong>the</strong> Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an African Ra<strong>in</strong>forest<br />

Reserve and Mbulu, with a total overall population <strong>in</strong><br />

Cameroon and Nigeria <strong>of</strong> only about 270 weaned<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals. This total density is considerably less than<br />

that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> better known mounta<strong>in</strong> gorilla (Gorilla gorilla<br />

ber<strong>in</strong>gei). In <strong>the</strong> past, <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> threat to survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

gorilla was hunt<strong>in</strong>g. But s<strong>in</strong>ce 1998, when biological<br />

studies began <strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong>, hunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> apes all but<br />

ceased through local community hunt<strong>in</strong>g bans. Now by<br />

far <strong>the</strong> greatest threat fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Cross River gorilla is<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ued habitat fragmentation. Presently, <strong>the</strong> Cross<br />

River gorillas are restricted to highland areas where <strong>the</strong><br />

terra<strong>in</strong> is difficult to access and hunt<strong>in</strong>g pressure is thus<br />

lower. The gorillas appear to be unwill<strong>in</strong>g or unable to<br />

cross large tracts <strong>of</strong> lowland forest to <strong>in</strong>teract with o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

groups. The road from Mamfe to Akwaya, under<br />

construction, will almost certa<strong>in</strong>ly have an effect on any<br />

current gorilla movements between <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest<br />

Reserve and adjacent Mbulu forest, <strong>the</strong>reby <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> isolation <strong>of</strong> Cross River gorilla groups. If lowland<br />

forest corridors cannot be secured and if gorillas are<br />

deterred from us<strong>in</strong>g lowland corridors to reach gorilla<br />

groups <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r highland sites, <strong>in</strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g and loss <strong>of</strong><br />

genetic variation may imperil <strong>the</strong>se isolated groups.<br />

The forests <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> are also important for a<br />

great diversity <strong>of</strong> birds as recognized by Birdlife<br />

International when it designated <strong>the</strong> Reserve an<br />

Important Bird Area. Surveys by Languy and Motombe<br />

(this volume) registered 309 species, br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> total<br />

count for TFR to 313 species. Of <strong>the</strong>se, n<strong>in</strong>e species are<br />

classified threatened, one endangered, and two<br />

vulnerable with<strong>in</strong> IUCN categories. Sixteen additional<br />

bird species have restricted ranges—<strong>the</strong>ir total world<br />

range is less than 50,000 km 2 . Two species are new<br />

records for Cameroon, while an additional 20 species<br />

extend <strong>the</strong>ir range with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country (Languy and<br />

Motombe this volume).<br />

Reptile diversity is equally impressive. The present<br />

study described 81 species <strong>in</strong> TFR, or about 30% <strong>of</strong><br />

Cameroon’s total (LeBreton et al. this volume). An<br />

additional three undescribed species were collected<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g recent visits, and several endemics and regional<br />

endemics as well as endangered species have been<br />

registered.

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve<br />

Butterflies (111 species, O’Kah this volume) and<br />

dragonflies (67 species, Vick this volume) have high<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> diversity. Both groups are important <strong>in</strong>dicators<br />

<strong>of</strong> forest change. Likewise, 54 species <strong>of</strong> fish were<br />

registered, many <strong>of</strong> which provide an important prote<strong>in</strong><br />

source to local communities (Mdaihli et al. this volume).<br />

Flora also proves to be extremely rich with more<br />

than 950 species <strong>of</strong> plants registered over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> present surveys. Of <strong>the</strong>se, 351 species were trees with<br />

diameters greater than 10 cm (Sunderland et al. this<br />

volume). All species were registered <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity<br />

plots <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve that will be <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> long-term<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong>’s forest at different elevations.<br />

8 About <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Project<br />

The <strong>Takamanda</strong> Project arose from a general <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> area expressed by numerous government agencies<br />

and non-governmental organizations that have been<br />

conduct<strong>in</strong>g biodiversity assessments <strong>in</strong> Cameroon and<br />

neighbor<strong>in</strong>g Nigeria. Large mammal studies focus<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cross River gorilla <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Akwaya area, supported by<br />

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and <strong>the</strong> Wildlife<br />

Conservation Society (WCS), were <strong>in</strong>itiated <strong>in</strong> late 1997<br />

and are cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g. In early 2000, <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian<br />

Institution conducted a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g course (“Biodiversity<br />

Assessment and Monitor<strong>in</strong>g for Adaptive Management”)<br />

<strong>in</strong> Mundemba, Cameroon, where participants expressed<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir desire to conduct biodiversity assessments <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve. Follow-up activities led to<br />

<strong>the</strong> current project. The authors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> various chapters<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ated field teams <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reserve. Primary<br />

objectives follow.<br />

• Identify key habitats us<strong>in</strong>g cartographic <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

and remote sens<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

• Describe forest structure, composition, and diversity.<br />

• Determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> current conditions (species<br />

composition, frequency <strong>of</strong> encounters, population<br />

densities) <strong>of</strong> key taxonomic groups, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g large<br />

mammals, birds, reptiles, and selected arthropods.<br />

• Ga<strong>the</strong>r and understand <strong>in</strong>digenous knowledge on <strong>the</strong><br />

species and <strong>the</strong>ir uses.<br />

• Evaluate fisheries activities.<br />

• Develop land-use change maps.<br />

This volume presents <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surveys,<br />

which were conducted by numerous researchers and<br />

agencies. It provides an important first step <strong>in</strong><br />

document<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> impressive biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an area that<br />

has high conservation priority <strong>in</strong> Cameroon. Our goal is<br />

to provide a solid foundation for future conservation and<br />

management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve and <strong>the</strong><br />

species that call it <strong>the</strong>ir home.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

We gratefully acknowledge <strong>the</strong> contribution <strong>of</strong> all<br />

authors and <strong>the</strong>ir respective organizations. We thank <strong>the</strong><br />

Smithsonian Institution for its support and <strong>the</strong><br />

International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups for its<br />

fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vegetation studies and <strong>the</strong> current<br />

publication. Thanks to Dan Slayback for prepar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

maps.<br />

References<br />

Comiskey, J. A., F. Dallmeier, and A. Alonso. 2000.<br />

Framework for assessment and monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity. Pages 63-73 <strong>in</strong>: Lev<strong>in</strong>, S. ed.<br />

Encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity: Volume 3. San<br />

Diego, CA: Academic Press.<br />

Critchley, W. R. 1968. F<strong>in</strong>al report on <strong>Takamanda</strong><br />

gorilla survey. Unpublished report to W<strong>in</strong>ston<br />

Churchill Memorial Trust (typescript).<br />

Dallmeier, F., A. Alonso, and M. Jones. 2002.<br />

Plann<strong>in</strong>g an adaptive management process for<br />

biodiversity conservation and resource<br />

development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Camisea River Bas<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Environmental Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Assessment<br />

76(1): 1-17.<br />

Davis, S. D., V. H. Heywood, and A. C. Hamilton.<br />

1994. Centres <strong>of</strong> Plant Diversity: A Guide and<br />

Strategy for <strong>the</strong>ir Conservation. Volume 1:<br />

7<br />

SI/MAB Series #8, 2003

8 Sunderland-Groves et al.<br />

Europe, Africa, South West Asia and <strong>the</strong> Middle<br />

East. Cambridge, UK: IUCN Publications Unit.<br />

Etuge, M. 1998. Botanical collections and<br />

classifications <strong>of</strong> forest types throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve. Report to<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Surveys Project CM 00.36.02,<br />

WWF-Cameroon.<br />

Gartlan, S. 1989. La Conservation des Ecosystemes<br />

forestiers du Cameroon. IUCN Programme pour<br />

les Forets Tropicales. Gland. Switzerland: IUCN.<br />

Groombridge, B., and M. D. Jenk<strong>in</strong>s. 2000. Global<br />

Biodiversity: Earth’s Liv<strong>in</strong>g Resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

21st Century. Cambridge, UK: UNEP-World<br />

Conservation Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Centre.<br />

Groves, J. L. 2002. Good news for <strong>the</strong> Cross River<br />

Gorillas? Gorilla Journal (24): 12.<br />

Groves, J. L., and F. Maisels. 1999. Report on <strong>the</strong><br />

large mammal fauna <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest<br />

Reserve, South West Prov<strong>in</strong>ce, Cameroon, with<br />

special emphasis on <strong>the</strong> gorilla population.<br />

Unpublished report to WWF Cameroon.<br />

IUCN. 2000. 2000 IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened<br />

Species. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge,<br />

UK: IUCN<br />

Lawson, G. W. 1996. The Gu<strong>in</strong>ea-Congo lowland<br />

ra<strong>in</strong> forest: An overview. Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh Section B Biological<br />

Sciences 104: 5-13.<br />

Letouzey, R. 1985. Notice de la Carte<br />

Phytogeographique du Cameroon. Toulouse,<br />

France: Institute de la Carte Internationale de la<br />

Vegetation.<br />

March, E. W. 1957. Gorillas <strong>of</strong> eastern Nigeria. Oryx<br />

4: 30-34.<br />

Olson, D. M., E. D<strong>in</strong>erste<strong>in</strong>, E. D. Wikramanayake,<br />

N. D. Burgess, G. V. N. Powell, E. C.<br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong>: <strong>the</strong> Biodiversity <strong>of</strong> an African Ra<strong>in</strong>forest<br />

Underwood, J. A. D’Amico, I. Itoua, H. E.<br />

Strand, J. C. Morrison, C. J. Loucks, T. F.<br />

Allnutt, T. H. Ricketts, Y. Kura, J. F. Lamoreux,<br />

W. W. Wettengel, P. Hedao, and K. R. Kassem.<br />

2001. Terrestrial ecoregions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world: A new<br />

map <strong>of</strong> life on earth. Bioscience 51(11): 933-938.<br />

ONADEF. No date. Carte Forestiere d’Akwaya: NB-<br />

32-XVI. Scale 1:200 000.<br />

Sanderson, I. T. 1940. The mammals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> north<br />

Cameroon forest area. Transactions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Zoological Society <strong>of</strong> London 14: 623-725.<br />

Sarmiento, E. E., and J. F. Oates. 2000. The Cross<br />

River Gorillas: A dist<strong>in</strong>ct subspecies Gorilla<br />

gorilla diehli Matschie (1904). American<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History Novitates 3304.<br />

Schmidt-Soltau, K., M. Mdaihli, and J. S. O. Ayeni.<br />

2001. Socioeceonomic basel<strong>in</strong>e survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve. Unpublished report<br />

to PROFA (GTZ-MINEF) Office, Mamfe.<br />

Struhsaker, T. T. 1967. Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary report on a survey<br />

<strong>of</strong> high forest primates <strong>in</strong> West Cameroon.<br />

Report to Rockefeller University and <strong>the</strong> New<br />

York Zoological Society.<br />

Thomas, D. 1988. Status and Conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Takamanda</strong> Gorillas (Cameroon). F<strong>in</strong>al Report,<br />

WWF-1613. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: WWF-USA.<br />

White, F. 1983. The Vegetation <strong>of</strong> Africa. Paris:<br />

UNESCO.<br />

World Wildlife Fund. 1990. Cross River National<br />

Park (Okwango Division): Plan for Develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> Park and Its Support <strong>Zone</strong>. London: WWF-<br />

UK.<br />

World Wildlife Fund. 2001. Terrestrial Ecoregions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

World: A New Map <strong>of</strong> Life on Earth. Web page:<br />

http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/pr<strong>of</strong>iles/terres<br />

trial_at.html.

Adaptive Management: A Framework for Biodiversity Conservation<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong> Forest Reserve, Cameroon<br />

1 Introduction<br />

James A. Comiskey and Francisco Dallmeier<br />

As <strong>the</strong> world’s human population <strong>in</strong>creases, <strong>the</strong> threat to<br />

biodiversity becomes greater (WRI 2000). The situation<br />

is much more pronounced <strong>in</strong> tropical regions, with sub-<br />

Saharan Africa expect<strong>in</strong>g a rise <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current population<br />

<strong>of</strong> 133 million to an estimated 189 million by 2020 and<br />

307 million by 2050. For Cameroon, a country with 18<br />

protected areas cover<strong>in</strong>g just over 2 million has, or 4.4%<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country (WRI 2001), <strong>the</strong> current population <strong>of</strong><br />

about 15 million is estimated to <strong>in</strong>crease to 20 million by<br />

2020 and 31 million by 2050. The associated <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

demand for natural resources is likely to be expressed<br />

through land clearance for agriculture and bushmeat<br />

hunt<strong>in</strong>g at levels far beyond those now experienced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

region. The demand for bushmeat has had <strong>the</strong> greatest<br />

impact on regional biodiversity, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> localized<br />

species ext<strong>in</strong>ctions (Eves et al. 2002). Under <strong>the</strong>se<br />

circumstances, <strong>the</strong>re is an urgent need to protect and<br />

study what biodiversity rema<strong>in</strong>s and develop strategies<br />

for its conservation.<br />

Southwestern Cameroon and adjacent sou<strong>the</strong>astern<br />

Nigeria are known as an important area for biodiversity<br />

(Obot and Ogar 1997, Sunderland-Groves et al. this<br />

volume). The Gu<strong>in</strong>eo-Congolian ra<strong>in</strong>forest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area is<br />

unique because <strong>of</strong> high ra<strong>in</strong>fall levels (White 1983) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> highlands that provide a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

habitats for flora and fauna. The forests <strong>of</strong> <strong>Takamanda</strong><br />

Forest Reserve (TFR), located <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost tip <strong>of</strong><br />

Cameroon’s Southwest Prov<strong>in</strong>ce and rang<strong>in</strong>g from 100<br />

to 1,500 m <strong>in</strong> elevation, are <strong>of</strong> particular value<br />