BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET

BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1. uONTROL NUMBER 2. SUBJECT CLASSIF! CT:ON (695T<br />

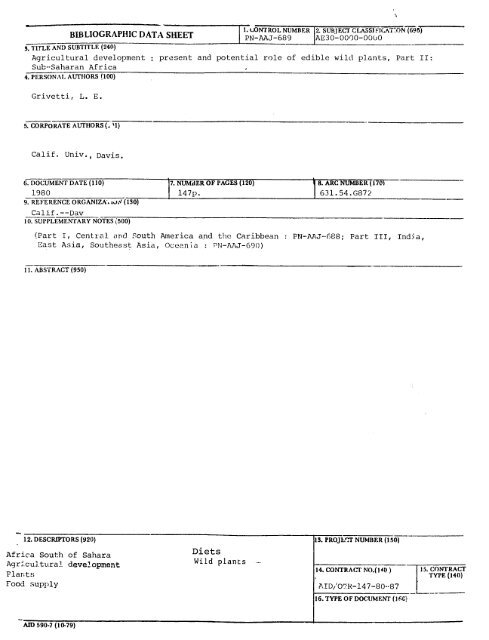

<strong>BIBLIOGRAPHIC</strong> <strong>DATA</strong> <strong>SHEET</strong> PN-AAJ-689 AE30-0000-00o0<br />

3. TITLE AND SUBTITLE (240)<br />

Agricultural development present and potential role of edible wild plants, Part II:<br />

Sub--Saharan Africa<br />

4. PERSONAL AUTHORS f100)<br />

Grivetti, L. E.<br />

5. CORPORATE AUTHORS (. 1)<br />

Calif. Univ., Davis.<br />

6. DOCUMENT DATE (110)<br />

1980<br />

9. REFERENCE ORGANIZA. iV (130)<br />

Calif. --Day<br />

10. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (500)<br />

7.NUMER<br />

l47p.<br />

(Part I, Central ard South America and the Caribbean<br />

East Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania : PN-AAJ-690)<br />

11. ABSTRACT (950)<br />

OF PAGES (120) 8. ARC NUMBER (1I0<br />

631.54.G872<br />

: PN-AAJ--688; Part III, India,<br />

12. DESCRIPTORS (920) 13. PROJL'T NUMBER (150)<br />

Africa South of Sahara<br />

Agricui.tural deve.opment<br />

Plants<br />

Food supply<br />

AID 590-7 (10-79)<br />

Diets<br />

Wild plants .. 14. CONTRACT NO.(]1)<br />

AIDi'OTR-147-80--87<br />

16. TYPE OF DOCUMENT (160?<br />

1. CONTRACT<br />

TYPE (140)

AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: PRESENT AND POTENTIAL<br />

ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS<br />

PART II<br />

SUB-SAHAIRAN AFRICA<br />

November 1980

REPORT TO THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE<br />

AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT<br />

AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: PRESENT AND POTENTIAL<br />

ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS<br />

PART 2<br />

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA<br />

by<br />

Louis Evan Grivetti<br />

Departments of Nutrition and Geography<br />

University of California<br />

Davis, California 95616<br />

With the Research Assistance of:<br />

Christina J. Frentzel<br />

Karen E. Ginsberg<br />

Kristine L. Howell<br />

Britta M. Ogle<br />

1980

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

INTRODUCTION ------ 1. i-------------<br />

M[ETHODS ------ 2.<br />

WILD PLANTS AS HUMAN FOOD IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA<br />

Introduction to the Region and Theme --------- 3.<br />

Introduction to Botanical Resources for Sub-Saharan Africa ---------- 9.<br />

West Africa: General ---- --------- - --- ---- 20.<br />

West Afriza: Botanical/Dietary Data by State<br />

Page<br />

Senegal 21.<br />

Mali 21.<br />

Ghana 21.<br />

Nigeria 22.<br />

Cameroons 23.<br />

Zaire (Congo) ------- 23.<br />

East Africa: General --------------------- 35.<br />

East Africa: Botanical/Dietary Data by State<br />

Chad-Sudan-Ethiopia-Somaliland 35.<br />

Uganda ---------- ----------- 37.<br />

Kenya 38.<br />

Tanzania (Tanganyika; Zanzibar) 39.<br />

South Africa: General 51.<br />

South Africa: Botanical/Dietary Data by State<br />

Swaziland-Lesotho-Malawi-Mozambique 51.<br />

Zimbabwi (Southern Rhodesia) and Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) --- 52.<br />

Republic of South Africa 54.

TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED)<br />

WILD PLANTS AS HUMAN FOOD IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA (CONTINUED)<br />

South Africa: Botanical/Dietary Data by State (Continued)<br />

Page<br />

Republic of Botswana 58.<br />

DISCUSSION AND SYNTHESIS ------------------------- 82.<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS --------------- ------------------ -- 86.<br />

APPENDICES<br />

1. Sub-Saharan Africa Search Request ---------------- 88.<br />

2. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa. Being an Appendix<br />

to the Flora of West Tropical Africa by J. Hutchinson and J.<br />

M. Dalziel: Sample Page and Sample Index 89.<br />

3. Woody Plants of Ghana. With Special Reference to Their Use, by<br />

F. R. Irvine: Sample F3ges ------------------------ 91.<br />

4. The Role of Wild Plants in the Native Diet in Ethiopia, by Amare<br />

Getahun: Table II, Wild Edible Plants of Ethiopia ---------- 102.<br />

REFERENCES CITED --------- ---- ------------ ------ 109.

TABLES<br />

1. Library Research Organizational Plan ----- 12<br />

2. Classification of African Cultivated Plants by Type and Origin -------- 13<br />

3. Wild Edible Foods of /Gwi and //Gana Bushmen ------------- 14<br />

4. Plants Used by Bushmen in Obtaining Food and Water --------------- 15<br />

5. Nutrient Composition of Some Edible Wild Fruits; Transvaal,<br />

Republic of South Africa ----------- 16<br />

6. Staple Wild Plants and Famine Foods of the Sandawe------ 17<br />

7. Edible Wild Plants of Zanzibar and Pemba --------------- 19<br />

8. Supplementary and Emergency Wild Food Plants of West Africa ----------- 24<br />

9. Edible Semi-Cultivated Leaves of West Africa --------------- 29<br />

10. Edible Wild Plants from Bamako, Mali ------------------ 30<br />

11. Nutritive Value of Some Ghanaian Edible Wild Plants --------------- 31<br />

12. Indigenous Wild Edible Plants of Nigeria ----------------- ---- 32<br />

13. Edible Wild Plants, Benin, Nigeria ------------ 33<br />

14. Nutritional Value of Edible Mushrooms, Upper-Shaba, Zaire ---- 34<br />

15. Edible Wild Plants of the Zaghawa, Sudan and Chad ----------- 41<br />

16. Indigenous Edible Wild Plants, West Nile and Madi Districts, Uganda --- 42<br />

17. Edible Wild Plants of the Masai and Kipsigis, Kenya --------- 44<br />

18. Indigenous Plants Used as Food by East African Coastal Fishermen ------ 47<br />

19. Edible Wild Plants, Shinyanga District, Sukumaland, Tanzania --- 49<br />

20. Edible Wild Plants, Lushoto District, Tanzania ---- 50<br />

21. Swazi Edible Wild Plants ------------------- 64<br />

22. Edible Wild Plants of the baSotho --------------------- 65<br />

23. Edible Wild Plants of Malawi ---------------- 66<br />

24. Gwembe Tonga Edible Wild Plants, Zambia -------- 70<br />

Page

TABLES (CONTINUED)<br />

25. Xhosa Edible Wild Plants, Transkei, Republic of South Africa ---------- 74<br />

26. Pedi Edible Wild Plants, Republic of South Africa ----- 75<br />

27. Nutritional Value of Selected Edible Wild Plants, Natal, Republic<br />

of South Africa ------------------------------------------------ 76<br />

28. Anti-Pellagragenic Properties of Selected Edible Wild Plants, Natal,<br />

Republic of South Africa ------------------------ 77<br />

29. Edible Wild Cucumbers (Cucurbitaceae) of Botswana and Selected<br />

iv.<br />

Page<br />

Kalahari Edible Species 78<br />

30. Edible Wild Plants Used by the Moshaweng Tlokwa, Botswana ------ 79<br />

31. Comparative Utilization of Edible Wild Plants: Agro-Pastoral<br />

Moshaweng Tlokwa and !Kung, /Gwi, =/Kade San, and !Xo<br />

Bushman Societies ------------------ -------- 81

INTRODUCTION<br />

Before domestication of plants and animals all humans lived as hunter<br />

gatherers. The agricultural revolution, first in China and Southeast Asia at<br />

least 20,000 years ago, radically altered human economic systems and food pat<br />

terns, permitting the development of agricultural, pastoral, and ultimately<br />

urban societies. While domesticated plants allowed expansion of human activi<br />

ties, with associated social and technological developments, domestication<br />

also initiated a basic human nutritional paradox. As reliance upon domesti<br />

cated foods increases, dietary diversity and food selection diminishes -- as<br />

food selection diminishes, the probability that all essential nutrients can be<br />

obtained from the diet also diminishes.<br />

While principle efforts in agricultural development, heretofore, have been<br />

directed toward improving productivity -- not the diversification of domesticat<br />

ed plants and animals -- a major question may be posed: can nutritionally im<br />

portant wild plants offer a legitimate focus for development research? Recent<br />

reports by Doughty (1979a;1979b), National Research Council/National Academy of<br />

Sciences (1975; 1979), Nietschmann (1971), Pirie (1962; 1969a; 1969b), Robson<br />

(1976), von Reis (1973), and Wilkes (1977) suggest that substantial economic and<br />

nutritional gains can be achieved by increasing dietary utilization of wild<br />

plants.<br />

Such suggestions form the objective of this report, to explore the role<br />

wild plants already play in human diet in Sub-Saharan Africa. To accomplish<br />

this objective three goals are established: 1) document dietary uses for wild<br />

plants, using published accounts of the past 150 years, 2) identify the relative<br />

dietary-nutritional importance of selected species, and 3) examine the research

potential for such species within the context of agricultural development as<br />

part of existing USAID themes of improving agriculture and nutrition in Third<br />

World nations.<br />

Basic study questions associated with these objectives may be identified.<br />

In regions or societies where wild plants are used as human food, are the plants<br />

central or peripheral to maintaining dietary quality? Is their use seasonally<br />

important, or is utilization common throughout the agricultural year? Do wild<br />

species complement or duplicate energy and nutrients obtained from domesticated<br />

field crops? What role do wild plants have in maintaining nutritional quality<br />

of diet during drought and periods of associated social unrest? Should research<br />

on dietary wild plants be sponsored directly by USAID within the context of<br />

agricultural development, or be assigned a low USAID priority?<br />

METHODS<br />

This contract, awarded September 1980, was designed for library research<br />

only; no field surveys or correspondence with appropriate governmental agencies<br />

were initiated due to time and financial constraints. Four assistants trained<br />

in library research-retrieval methods were employed to assist the principal<br />

investigator. One computer literature-retrieval search was coordinated using<br />

DIALOG/AIRS systems available through the Peter J. Shields library, University<br />

of California, Davis. This system, drawing from a publication data base exceed<br />

ing 12 million articles is a cross-tabulation process whereby key words associat<br />

ed with wild plant use in diet were matched with respective countries of Sub-<br />

Saharan Africa (Appendix 1). The literature search using the DIALOG/AIRS system<br />

was disappointing, yielding less than twenty suitable references. Accordingly,<br />

a standard literature search on dietary wild plants was initiated using a method<br />

ology outlined in Table 1. Basic anthropological, botanical, geographical,<br />

2.

medical, nutritional, and sociological journals appropriate to each country<br />

were scanned for the years 1975-1980. Any journal containing one article<br />

appropriate to the topic of human utilization of wild plants as food during<br />

the most recent five years was scanned chronologically to volume 1; if no*<br />

suitable article appeared within the survey period, the journal was not<br />

further inspected.<br />

Each article identified was read, reference cards prepared, and coded<br />

for region, country, ethnic group, and specific plants utilized. Information<br />

was summarized on index cards to permit rapid assembly of data. Data<br />

presented in subsequent sections of this report are arranged by general region<br />

then by specific reports on pla-Lt use within each country. The accounts<br />

are quite diverse and time of publication is not the criterion of quality; stme<br />

accounts are merely passing reference to human dietary use of wild plants while<br />

others provide detailed botanical documentation by Latin terminology. Still<br />

others give nutritional information on the vitamins and minerals by plant species.<br />

Following the presentation of information on wild plant use as human food<br />

in Sub-Saharan Africa will be a summary and recommendations.<br />

WILD PLANTS AS HUMAN FOOD IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA<br />

Introduction to the Region and Theme<br />

The question of food production within the tropics and the interrelation<br />

ships between domesticated and wild species has long attracted botanists and<br />

social scientists (Anderson, 1952). At first inspection it appears easy to<br />

distinguish wild from domesticated species; cultivated from uncultivated; diet<br />

ary from non-dietary species. On close examinatiun, however, these semantical<br />

boundaries become blurred. Numerous wild plants are carefully cultivated;<br />

former domesticated species may dot long abandoned humah settlements; and many<br />

3.

medicinal plants are ingested, providing important nutritional returns. Thus,<br />

any approach to understanding the interrelationships between dietary roles of<br />

wild or domesticated species must be carefully documented, especially given the<br />

long historical-archaeological history of plant use exhibited in Sub-Saharan<br />

Africa.<br />

The relationships between cultivated field crops, forest-bush destruction,<br />

and dietary use of domesticated and wild food resources are considered in depth<br />

by several writers on African agrarian, agricultural systems, among them Allan<br />

(1965), de Schlippe (1956), Gourou (1955), and McLoughlin (1970). All consider<br />

patterns of variation within shifting cultivation systems and address the question<br />

whether technological change automatically improves food sufficiency. Theynote<br />

that under tropical conditions shifting cultivation -- a mixed blessing -- has<br />

generally provided substantial quantities of food and permitted maintainence of<br />

quality human nutrition.<br />

Other writers have examined African food production systems throughout the<br />

tropical regions of the continent. Some, like Schnell (1957), Murdock (1960),<br />

Jones (1961), and Joy (1966), have described dietary patterns and food resources<br />

whereas others, among them Githens and Wood (1943), Baker (1949), Lagercrantz<br />

(1950), and Jardin (1967), have focused on regional patterns of food intake.<br />

It is the view of this writer, however, that any examination of African<br />

food systems must consider the processes associated with plant and animal do<br />

mestication as well as the shift from hunting-gathering to agriculture. Current<br />

evidence advanced by Chang (1973; 1977), Solheim (1971), and Gorman (1969) sug<br />

gests domestication of plants first evolved in east China, subsequently in the<br />

Middle East and Africa. Whatever the dates, direction, or impetus for domesti<br />

cation, two regions of Africa must be considered early centers of agricultural<br />

activity; the Egyptian Nile valley and highland Ethiopia. Murdock (1959, pp.<br />

4.

64-77) advanced a third region in West Africa, among the ancestors of the<br />

Nuclear Mande peoples.<br />

Archaeological data documenting early human use of wild plants as food<br />

and the subsequent shift to cultivation in Africa have been summarized by<br />

Clark (1959; 1960; 1962; 1968) and Seddon (1968, pp. 489-494). Murdock (1959,<br />

pp. 17-24) presents a synthesis of African food patterns based on domesticat<br />

ed plants that reached Africa from four geographical sources: Southwest Asia,<br />

Southeast Asia, Europe, and the New World (Table 2). Other authors, specifical<br />

ly Greenway (1944a; 1944b), Goodwin (1939), and Mc1aster (1963), have reviewed<br />

the geographical origins and dispersals of non-African foods and their result<br />

ing nutritional role in Eastern and Southern Africa.<br />

The most important archaeological record of food in Africa has been reveal<br />

ed along the Nile Valley where recent suggestions by Wendorf et aL (1970) and<br />

Wendorf et al. (1979) show wild cereals used as human food at least by 19,000<br />

B.C. in the vicinity of southern Egypt/northern Sudan. There, human use of wild<br />

barley, teff, and other cereals with associated tool technologies, suggests a<br />

shift from gathering to insipient agriculture. Such early archaeological data<br />

become soundly based with research on wild and domesticated plant foods utiliz<br />

ed by the pre-dynastic ancient Egyptians (before 3200 B.C.) and subsequent mono<br />

graphs outlining dietary use of wild and domesticated plants throughout the<br />

historical periods of Egyptian civilization. Of specific importance in assembl<br />

ing the ancient data on wild and domesticated plant use are monographs by<br />

Daressy (1922) on wild rice; Keimer (1924) on Egyptian garden plants; Lauer et<br />

al. (1951) on early cereals associated with the site of Saqqara; Loret (1886;<br />

1892; 1893) on the plant foods used by the ancient Egyptians; Ruffer<br />

(1919) on the diet and nutritional status of the Egyptians; Schweinfurth (1873;<br />

5.

1883) on diet and plants in ancient Egypt; and research by Unger (1860) and<br />

b6nig(1886) on the plants known, named, and used by the ancient Egyptians<br />

(see also Darby et al., 1977, Vols. 1 and 2).<br />

The aridity of the Nile valley protected t-b archaeological remains of<br />

ancient plant foods and the dry zones of West Africa also provide a wealth<br />

of information on Medieval African diet and the use of wild plants. Lewicki<br />

(1963; 1974) identified early travel accounts by Arab geographers and physicians<br />

noting use throughout much of West Africa wild grasses as human food, namely<br />

Panicum turgidum, Sorghum virgatum, Poa abyssinica, Eragrostis spp., Cenchrus<br />

echinatus, and Pennisetum distichum. Lewicki also notes Medieval use of se<br />

veral West African wild fruits, specifically Blighia sapida, Adansonia digitata,<br />

Balanites aegyptica, Hyphaene thebaica, Ziziphus jujuba, Ziziphus mauritiana,<br />

Ziziphus spina-Christi, Ziziphus mauritiana, Ampelocissus bakeri, wild forms of<br />

Phoenix dactylifera, and numerous unidentified "truffles". Parallel data on<br />

the use of domesticated and wild plants as food for the Egyptian Nile valley<br />

have been gathered by Schweinfurth (1888; 1912).<br />

Existing in the 20th century and forming a bridge between the archaeological<br />

data on wild plants and any understanding of the shift from gathering to plant<br />

domestication are numerous African societies still living as hunter-gatherers.<br />

Hunter-gatherer ethnobotanical/dietary utilization of wild plants has attracted<br />

botanists, physicians, and social scientists for nearly one hundred years, es<br />

pecially on the Bushman societies of southern Africa. Early research on wild<br />

dietary plants use by Bushmen was conducted by Stow (1910, pp. 44-45, 54-61)<br />

and Theal (1910, pp. 36-38), with subsequent notes by Dornan (1925, pp. 114<br />

123), Fourie (1928, pp. 98-103), Schapera (1930, pp. 91-102, 127-147), and<br />

Dunn (1931, pp. 28-31). These early works, however, focused on nutritional<br />

6.

odditities of Bushman diet and must be considered ethnocentric in organization<br />

when evaluating the dietary role of wild plants.<br />

Systematic examination of the dietary ecological relationships between<br />

wild plants, seasonality, and Bushman nutritional status stem from the report<br />

of Tobias (1956) alerting social scientists to field research opportunities<br />

on these Kalahari peoples. Subsequently, teams of social scientists and phy<br />

sicians have spent nearly twenty-five years conducting work on Bushman food<br />

habits, the quest for food, and nutritional status. Many of these reports are<br />

classic and deserve mention in any assessment of cultural nutrition, especial<br />

ly accou-its by Thomas (1959, pp. 102-113), Marshall (1960; 1961), and Lee (1965;<br />

1968; 1969), who worked among !Kung Bushman populations describing food procure<br />

ment strategies during wet and dry years, social division of scarce plant food<br />

resources, and ultimately examining the associations between sound Bushman diet<br />

and good health.(see also J. Tanaka, 1976).<br />

Other important research on wild plants used by Bushman societies of the<br />

Kalahari has been conducted by Heinz and Maguire (1974) and Heinz (1975) on the<br />

!Xo Bushman and that by Silberbauer (1965) and Tanaka (1969) on the /Gwi and<br />

//Gana Bushmen of the central Kalahari (Table 3).<br />

Medical-nutritional research on Bushman societies of southern Africa has<br />

also focused on the dietary role played by wild plant foods in maintaining<br />

adequate nutrition during periods of drought and environmental stress. Early<br />

research blending botany-medicine-nutrition was conducted by Maingard (1937),<br />

Brock and Bronte-Stewart (1960), Bronte-Stewart and Brock (1960), Truswell and<br />

Hansen (1968), Truswell et al. (1969), Truswell (1977), and Wilmsen (1978).<br />

Central to these works is the theme of sound Bushman diet and a Bushman economy<br />

based on wild plant consumption. Perhaps the most important of the nutritional<br />

7.

eports, however, is that by Metz et al. (1971) documenting clearly that rapid<br />

acculturation may lead to serious deterioration of health and nutritional<br />

status and suggesting that dietary deficiencies may have resulted initially<br />

(historically) after the shift from hunting-gathering to agrarian food pro<br />

duction.<br />

Complementing these cultural and medical-nutritional accounts of Bushman<br />

hunter-gatherers are reports providing nutritional data on the composition of<br />

wild plants used by these Kalahari peoples. Story (1958) presents information<br />

on more than seventy species (Table 4) while subsequent work by Wehmeyer (1966;<br />

1971) and Wehmeyer et al. (1969) includes information on six important wild<br />

foods and suggests that they be examined closely for potential economic/nutritional<br />

reward: Sclerocarya caffra (high in ascorbic acid and protein), Ricinodendron<br />

rautanenii (high in ascorbic acid and protein), Adansonia digita:.ta (high in<br />

ascorbic acid and protein), Bauhinia esculenta (high in protein), Carissa<br />

marcocarpa (high in ascorbic acid), and Vigna dinteri (high in calories) (Table<br />

5). Augmenting these reports is the important paper by Lee (1973) on mongongo<br />

(Ricinodendron rautanenii) and its dietary role in !Kung Bushman diet -- a role<br />

that casts serious doubt on the validity of the theme "Man the Hunter" and ele<br />

vates t'e important roles played by "Woman the Gatherer".<br />

Elsewhere in East Africa researchers have investigated the dietary role<br />

of wild plants in ot' hunter-gatherer societies. Newman (1970; 1975) con<br />

ducted basic research on the wild plants used by Sandawe hunters (Table 6), a<br />

topic also reviewed by Porter (1979, p. 70). In addition to identifying the<br />

basic wild staples of Sandawe, Newman noted important "famine" foods, plants<br />

consumed on: ing drought or periods of social distress that provide impor<br />

8.

tant nutrients and calories to diet, specifically Ceropegia spp., Coccinia<br />

trilobata, Commiphora caerulea, Dactyloctenium giganteum, Panicum hetero<br />

stachyum , Rynchosia comosa, and Thylachium africanum.<br />

Woodburn (1962-1963) provided vernacular terms for the edible wild plants<br />

used by Tindiga hunters while Tomita (1966) and Woodburn (1968; 1970; 1972)<br />

focused on the ecological-dietary relationships between wild plants and diet<br />

of Hadza (Hadzapi) bands, noting snecific use of Cordia gharaf, Cordia oralis,<br />

Grewia bicolor, Grewia villosa, Momordica spp., 0pilia spp., and Salradora<br />

persiea.<br />

Introduction to Botanical Resources for Sub-Saharan Africa<br />

Information on African botany is extensive. Most accounts provide not<br />

only taxonomic data, but include information on cultural uses, even dietary<br />

data. Many botanical texts, especially those by Hendrick (1919), Upton (1968),<br />

U3her (1974), and Tanaka (1976), consider the African continent, providing data<br />

on nearly 15,000 plants utilized by humans! Other resources, however, are more<br />

regional or thematic in orientation.<br />

The botany of West and Central Africa is especially well documented. Im<br />

portant contributions to West Africa as a region have been made by Irvine (1952a),<br />

Dalziel (1937), Hutchinson and Dalziel (1954; 1963; 1968), Lawson (1966), van<br />

Eijnatten (1968), Pille (1962), and Busson (1965) and Busson and Lunven (1963)<br />

(see Appendix 2). Specific country/national accounts providing detailed notes<br />

on edible wild plants have been produced by Berhaut (1954; 1967) for Senegal;<br />

Boughey (1955) on eastern Nigeria (Biafra) and by Holland (1922) on Nigeria;<br />

Chipp (1913) on the Ashanti territory of northern Ghana (Gold Coast) and Irvine<br />

(1960) on Ghana (see Appendix 3); Deighton (1957) on Sierra Leone; Percival<br />

(1968) on Gambia; Savonnet (1973) on Upper Volta; Williams'(1969) on Dahomey;<br />

and Sillans (1953) and Thomaq (19,1) on the Central African Republic,<br />

9.

Turning to East Africa, important botanical monographs may be noted for<br />

Kenya by Greenway (1937) and Dale and Greenway (1961). Eggeling and Dale (1951)<br />

have written on the botany of Uganda, while Williams (1949) (Table 7) and<br />

Fleuret (1979a; 1979b) have contributed extensively to the botany of Tanzania.<br />

Getahun (1974) produced a major work on the ethnobotany of Ethiopia, identi<br />

fying numerous edible wild plants (Appendix 4).<br />

The botany of Southern Africa has been especially well described. The classic<br />

work of Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) provides accounts of several thousand<br />

medicinal and toxic species (many consumed regularly as food), while Wilde et al.<br />

(1967) has identified the principal plants common throughout the Zambesi basin,<br />

a botanical zone extending through northern Botswana and South Africa, Zambia,<br />

Zimbabwe, and Malawi.<br />

Botanical monographs, with notes on edible food, have been produced by<br />

1972)<br />

Williamson (19551/and Binns (1976) for Malawi (Nyasaland) and for Zimbabwe<br />

(Rhodesia) by Orpen (1951) and Wilde (1952). The landlocked states of Lesotho<br />

(Basutoland) and Swaziland have been described, respectively, by Phillips (1918)<br />

and Compton (1966).<br />

Turning specifically to Botswana (Bechuanaland) the Kalahari and eastern<br />

thorn-bush grasslands have been research localities for numerous botanists and<br />

notes or monographs on economic plant use have been published by Miller (1952),<br />

Norton (1923), van Rensburg (1971; 1971b), Weare (1971), and Weare and Yalala<br />

(1971). A checklist of common Botswana plants (many edible) was compiled by<br />

an individual known only by his initials (REHA, 1966); this list was consulted<br />

by the present Triter when conducting field work in Botswana, 1973-1975, and<br />

is available through the Btswana National Archives.<br />

10.

The Republic of South Africa is also well represented by national and<br />

regional botanical publications. General works that include notes an wild<br />

plant use include those by Chippindall (n.d.) on wild grasses; de Winter et<br />

al. (1966) and Stapleton (1937) on trees of the Transvaal; and the work of<br />

Phillips (1938) on common weeds of South Africa (many with edible portions).<br />

Overviews of South African botanical regions may be obLained from Hutchinson<br />

(1946) while Zulu terminology for edible and non-edible species has been<br />

collected by Gerstner (1939). Other botanists have especially focused on<br />

1941),<br />

plant toxicology, for example Smith (1895) and Steyn (1934;/ who investi<br />

gated the toxic effects of many plants commonly consumed as dietary components<br />

by citizens of South Africa.

TABLES 1 - 7 FOLLOW<br />

TEXT RESUMES ON PAGE 20<br />

lla.

TABLE 1. Library Research Organizational Plan<br />

LITERATURE SOURCES<br />

TOPIC<br />

(Dietary Use of Wild Plants)<br />

STUDY REGIONS<br />

1) Central America, South America, Caribbean<br />

2) Sub-Saharan Africa<br />

3) South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania<br />

TIME CONSTRAINT: THREE WEEKS PER EACH REGION FOR LIBRARY RESEARCH<br />

PERSONNEL ASSIGNMENTS<br />

Research Assistant 1: works concerning anthropology and geography<br />

by study region<br />

Research Assistant 2: works concerning botany by study region<br />

Research Assistant 3: wor.ks of medical-nutritional content by<br />

study region<br />

Research Assistant 4: works of a regional nature that contain<br />

botanical, cultural, or mEdical-nutritional<br />

information<br />

1. General journals (multi-disciplinary)<br />

2. General books (multi-disciplinary)<br />

3. Specific journals (by discipline, study region, and country)<br />

4. Specific books (by discipline, study region, and country)<br />

5. Bibliographies (by discipline, study region, and country)<br />

6. Dissertations/Theses (by discipline, study region, and country)<br />

7. Abstract services (by discipline): Anthropology Abstracts; Food Science<br />

Abstracts; Geographical Abstracts; Nutrition Abstracts; World<br />

Agriculture, Economics, and Sociology Abstracts<br />

8. Current Contents (natural sciences. and social sciences)<br />

9. Science Citation Index (examination by key word; key word selected by<br />

topic, sub-theme, region, and country)<br />

10. Index Medicus (examination by key word; key word selected by topic, sub<br />

theme, region, and country)<br />

12.

TABLE 2. Classification of African Cultivated Plants by Type and Origin<br />

GEOGRAPHICAL SOURCE<br />

TYPE W. Africa Ethiopia SW Asia SE Asia Americas<br />

Cereal grains Fonio Eleusine Barley Rice Maize<br />

Pearl millet<br />

Sorghum<br />

Legumes Cow pea Broad bean Gram bean Haricot<br />

Chick pea Hyacinth beau<br />

Lentil bean Lima bean<br />

Pea Pigeon pea<br />

Sword bean<br />

Tubers and Coleus Ensete Beet Taro Malanga<br />

root crops Earth pea Chufa Yam Manioc<br />

Geocarpa Onion Peanut<br />

bean Radish Sweet potato<br />

Guinea yam<br />

Leaf and stalk Okra Cress Cabbage Jew's<br />

vegetables Lettuce mallow<br />

Vine and ground Fluted Grape Cucumber Pineapple<br />

fruits pumpkin Melon Eggplant Pumpkin<br />

Gourd Squash<br />

Watermelon Tomato<br />

Tree fruits Akee Date palm BanaLa Avocado<br />

Tamarind Fig Coconut Papaya<br />

Pomegranate palm<br />

Mango<br />

Condiments and Kola Coffee Coriander Ginger Cacao<br />

indulgents Roselle Fenugreek Garlid Hemp Red pepper<br />

Kat Opium Sugarcane Tobacco<br />

Textile plants Ambary Flax Cotton<br />

Oil plants Oil palm Castor oil Olive<br />

Sesame Remtil Rape<br />

SOURCE: Murdock (1959, p. 23)<br />

13.

TABLE 3. Wild Edible Foods of /Gwi and //Gana Bushmen<br />

Latin Terminology<br />

Citrullus lanatus<br />

Citrullus naudinanus<br />

Cucumis anguria<br />

Cucumis kalahariensis<br />

Coccinia rehmannii<br />

Raphionacme burkei<br />

Bauhinia macrantha<br />

Ochna pulchra<br />

Scilia spp.<br />

Aloe zebrina<br />

Grewia flava<br />

Grewia retinervis<br />

Terfezia spp.<br />

Grewia avellana<br />

Ximenia caffra<br />

Bauhinia esculenta<br />

Strophanthus spp.<br />

Brachystelma spp.<br />

Strychnos cocculoides<br />

Talinum crispatulum<br />

Talinum tenuissimum<br />

Oxygonum latum<br />

Vigna longiloba<br />

Kedrostis foetidiosima<br />

Corallocarpus bainesii<br />

Caralluma krobelii<br />

Vigna parviflora<br />

SOURCE: Tanaka (1969, pp. 6-7)

TABLE 4. Plants Used by Bushmen in Obtaining Food and Water<br />

Latin Terminology<br />

Acacia detinens Lannea edulis var glabrescens<br />

Acacia dulcis Mariscus congestus<br />

Acacia fleckii Momordica balsamina<br />

Acacia giraffae Ochna pulchra<br />

Acacia heteracantha Ophioglossum sarcophyllum<br />

Acacia unci-ata Pentarrhinum insipidum<br />

Adansonia digitata Pollichia campestris<br />

Aloe rubrolutea Raphionacme burkei<br />

Aloe zebrina Rhigozum brevispinosum<br />

Bauhinia esculenta Rhus commiphoroides<br />

Bauhinia macrantha Ricinodendron rautanenii<br />

Boscia albitrunca Royena sericea<br />

Burkea africana Sansevieria scabrifolia<br />

Cavalluma knobelii Sarcostemma viminale<br />

Catophractes alexandri Scilla cf. lancifolia<br />

Ceropegia tentaculata Sclerocarya caffra<br />

Ceropegia cf. leucotaenia Stapelia kwebensis<br />

Ceropegia cf. lugardae Strychnos cocculoides<br />

Ceropegia cf. mozambicensis Strychnos pungens<br />

Citrullus naudinianus Talinum arnotii<br />

Citrullus vulgaris Terfezia spp.<br />

Coccinia rehmanii Terminalia sericea<br />

Coccinia sessilifolia Typha capensis<br />

Combretum apiculatum Vigna dinteri<br />

Combretum coriaceum Vigna triloba<br />

Combretum imberbe Walleria nutans<br />

Commiphora pyracanthoides Ximenia americana var. microphylla<br />

Corallocarpus sphaerocarpus Ximenia caffra<br />

Corallocarpus welwitschii Ziziphus mucronata<br />

Cucumis hookeri<br />

Cucumis metuliferus<br />

Dichapetalum cymosum<br />

Dipcadi spp.<br />

Duvalia polita<br />

Ehretia rigida<br />

Eulophia cf. pillansii<br />

Eulophia spp.<br />

Fockea spp.<br />

Grewia avellana<br />

Grewia flava<br />

Grewia flavescens<br />

Grewia retinervis<br />

Grewia cf. bicolor<br />

Hydnora spp.<br />

Hyphaene ventricosa<br />

Ipomoea verbascoidea<br />

SOURCE: Story (1958, pp. 114-115)<br />

15.

TABLE 5. Nutrient Composition of Some Edible Wild Fruits; Transvaal, Republic<br />

of South Africa<br />

Species 100 gms mg. edible portion<br />

Protein Ca Fe Thiamin Riboflavin N. acid+ Vit. C<br />

Bequaertiodendron 0.9 20.0 0.69 0.07 0.03 1.64 14.1<br />

magalismontanum<br />

Sclerocarya caffra 0.5 6.2 0.10 0.03 0.05 0.25 67.9<br />

Landolphia capensis 1.0 11.1 0.34 0.03 0.53 1.89 60.1<br />

Strychnos pungens 1.6 45.5 0.91 2.74 1.85 1.78 21.9<br />

Carissa macrocarpa 0.5 22.6 0.56 0.08 0.08 0.31 74.1<br />

Adansonia digitata 3.0 387.0 2.20 0.57 0.16 1.78 213.0<br />

Ximenia caffra 3.1 5.9 0.20 0.04 0.04 0.81 22.5<br />

Dovyalis caffra 0.4 4.8 0.14 0.01 0.05 0.30 17-<br />

Coccinia sessilifolia 2.1 17.9 0.20 0.19 0.13 538.0<br />

SOURCE: Wehmeyer (1966, p. 1103)<br />

16.

TABLE 6. Staple Wild Plants and Famine Foods of the Sandawe<br />

Latin Terminology Portion Used Seasonality<br />

STAPLE WILD SPECIES<br />

Adansoila digitata Pulp; seeds Year round<br />

Berchemia discolor Fruit March-May<br />

Boscia mossambicensis Fruit November-December<br />

Brachystegia spiciformis Seeds January-April<br />

Bussea massaiensis Seeds August-November<br />

Canthirum burtii Fruit April-May<br />

Cissus trothae Fruit February-March<br />

Cordia ovalis Fruit February-March<br />

Cordia rothii Fruit February-March<br />

Cyphostemma knittelli Fruit January<br />

Delonix elata Seeds June-October<br />

Erythrococca antrovirens Seeds February-April<br />

Ficus fischeri Fruit April-May<br />

Ficus hochstetteri Fruit April-May<br />

Ficus sycmorus Fruit June-August<br />

Grewia bicolor Fruit April-May<br />

Grewia holstii Fruit April-November<br />

Grewia mollis Fruit March<br />

Grewia platyclada Fruit June-July<br />

Grewia similis Fruit March-April<br />

Haplocoelum foliolosum Fruit March-April<br />

Hydnora johannis Pulp December-May<br />

Kedrostis hirtella Fruit January-April<br />

Lannea floccosa Fruit March-May<br />

Lannea stuhlmanni Fruit March-May<br />

Maerua edulis Fruit January-April<br />

Momordica rostrata Fruit Year round<br />

Neorantenenia pseudo-pachyriza Pods March<br />

Opilia campestris Fruit February-March<br />

Peponium boqelii Fruit January-October<br />

Pouzolzia parasitica Leaves December-January<br />

Sclerocarya birrea Nuts April-May<br />

Strychnos innocua Fruit November-January<br />

Tapiphyllum floribundum Fruit April-May<br />

Vagueria acutiloba Fruit Year round<br />

Vangueria tomentosa Fruit Year round<br />

Ximenia americana Fruit Year round<br />

Ximenia caffra Fruit November-February<br />

Ziziphus mucronata Fruit November-December<br />

17.

Latin Terminology<br />

FAMINE FOODS<br />

Ceropegia spp.<br />

Coccinia trilobata<br />

Commiphora caerulea<br />

Dactyloctenium giganteum<br />

Panicum heterostachyum<br />

Rynchosia comosa<br />

Thylachium africanum<br />

Vigna sp.<br />

SOURCE: Newman (195, pp. 36, 38).<br />

TABLE 6 (CONTINUED)<br />

Portion Used<br />

Roots<br />

Leaves<br />

Roots<br />

Seeds<br />

Roots<br />

Roots<br />

Roots<br />

Roots<br />

Seasonality<br />

During drought<br />

"<br />

"<br />

"<br />

"<br />

"<br />

"<br />

18.

TABLE 7. Edible Wild Plants of Zanzibar and Pemba<br />

Latin Terminology Traditional Name Portion Used<br />

Dolichos spp. Bonavist Bean Seed<br />

Tacca spp. African Arrowroot Tuber<br />

Typhonodorum spp. Mgombakofi Tuber<br />

Adansonia digitata Baobab Leaves, shoots,<br />

fruits<br />

Amaranthus spp. Mchicha Leaf<br />

Cassia tora Kunde nyika Leaf<br />

Celosia spp. Mfungu Leaf<br />

Cleome strigosa Mwaangu Leaf<br />

Commelina spp. Kongwa Leaf<br />

Gynandropsis gynandra Mchicha Leaf<br />

Ipomoea reptans Mriba wa ziwa Leaf<br />

Jacquemontia tamnifolia Kikopwe Leaf<br />

Lobelia spp. Kisambare Leaf<br />

Moringa spp. Mronge Seeds, leaves<br />

Sesuvium spp. Mboga wa pwani Shoots<br />

Stachytarpheta Vervain Leaves<br />

Afromomum spp. Wild cardamom Seeds<br />

Cordia spp. Mkamasi Fruit<br />

Moringa spp. Mronge Root<br />

Bauhinia thonningii Mkuungo Pods<br />

Borassus spp. Mvumo Fruit<br />

Brexia madagascariensis Mfukufuku Fruit<br />

Eugenia cumini Java plum Fruit<br />

Landolphia spp. Mbungo Fruit<br />

Parinarium Mbura Fruit, kernels<br />

Zizyphus spp. Mkunazi Fruit<br />

Argemone spp. Mexican poppy Seeds<br />

Cassia occidentalis Wild coffee Seeds<br />

SOURCE: Williams (1949, pp. 39-44).<br />

19.

West Africa: General<br />

General accounts of agricultural. practices, food, diet, and nutrition for<br />

West Africa are numerous. Among the more important monographs on ethnobotany<br />

is that by Dalziel (1937), identifying more than one hundred wild edible plants<br />

with extensive data on the non-nutritional economic uses for thousands of West<br />

African plants (Appendix 2). The text by Johnston (1958) on food economies of<br />

West Africa is essential to understanding the agricultural-dietary-economic<br />

practices of the region, while more recent agro-economic resources by Tindall<br />

and Sai (1965) and Sai (1969) identify more than one hundred of the most common<br />

food resources encountered in West Africa. Regional accounts of diet and nut<br />

rition have been prepared for the nations of West Africa by May (1965; 1968)<br />

and May and McLellan (1970).<br />

The most siginificant references on edible wild plants common to West Africa<br />

stem from Irvine (1948a; 1948b) who identified more than one hundred species,<br />

providing important cultural and nutritional data on each. Irvine (1952a; 1952b)<br />

expanded this important earlier work to document famine foods regularly consum<br />

ed during periods of drought that possessed nutritionally sustaining properties<br />

(Table 8). Irvine (1956) continued his intensive research on edible wild plants<br />

of West Africa and produced amother monograph identifying more than 150 leafy<br />

plants serving regularly as food (Table 9).<br />

Specific accounts of wild foods include those by Hepper (1963) on dietary<br />

use of wild Kerstingiella spp. (Kersting's groundnut) and wild Voandzeia spp.<br />

(Bambara groundnut) long used throughout West Africa as a dietary component.<br />

Nzekwu (1961) presented a general botanical overview of the kola nut, while<br />

Adam (1969) identified the baobab fruit as high in ascorbic acid. An early<br />

account by Walker (1931) identified the edible mushrooms of Gabon.<br />

20.

West Africa: Botanical/Dietary Data by State<br />

Senegal<br />

Gamble (1957, p. 38), writing on the Wolof of Senegal, noted that<br />

children consume many wild fruits but did not identify the species. Toury<br />

(1961) provided minimal nutrient data on the composition of regional plant<br />

foods, while de Garine (1962), writing on the Wolor and Serer, commented<br />

briefly on the dietary role of wild plants but provided no identifications.<br />

Mali<br />

An important contribution by Diarra (1977) identified numerous<br />

species of edible plants common to the region near Bamako (Table 10).<br />

Ghana<br />

The dietary role of edible wild plants in Ghana was discussed by<br />

Chipp (1913) who identified nineteen edible species with no comment. Irvine<br />

(1961), however, identified more than seven hundred commonly used wild plants<br />

from Ghana and provided the nutritional composition for more than eighty (for<br />

an example of his work see Appendix 3). Adansi (1970, pp. 207-210) provided<br />

botanical/chemical data on three wild plants with unusual taste properties;<br />

Synsepalum dulcificum (magic berry) that makes sweet foods taste sour and sour<br />

foods sweet, while Dioscoreophyllum cumminsii and Thaumatococcus danielli are<br />

800-1500 times more sweet than sucrose. Watson (1971), writing on the nutri<br />

tional composition of selected foods from Ghana, reports protein and mineral<br />

values for exceptional wild species (Table 11).<br />

Information on the cultural-food data in Ghana stems from the work<br />

of Fortes and Fortes (1936) on the food practices of the Tallensi, with special<br />

reference to four widely consumed wild plants: Butyrospermum parkii, Parkia<br />

filicordea, Adansonia digitata, and Celtis integrifolia.<br />

21.

Byers (1961), working on leaf protein concentrate in Ghana, re<br />

states the commonly accepted view that LPC can contribute to resolving the<br />

world food crisis in societies where edible leaves already play important<br />

dietary roles.<br />

Nigeria<br />

Major researcl. on the dietary role played by wild plants in Nigeria<br />

has been summarized by Okiy (1960) who has identified the principal species<br />

consumed (Table 12). Johnson and Johnson (1976) also examined the economic<br />

uses of both wild and domesticated plants identified in rural markets at<br />

Benin City (Table 13).<br />

Despite the important works cited above there is relatively little<br />

cultural data on edible wild plants by ethnic group. Forde (1951, p. 6),<br />

writing on the Yoruba, notes domesticated foods are supplemented by limited<br />

quantities of wild green vegetables and fruits. Bradbury (1957, p. 25)<br />

worked among the Edo of Benin noting that they collect wild bush plants daily<br />

but provides no specifics. Netting (1968, p. 101) states that the Kofyar<br />

farmers of the Jos plateau use wild plants in sauces or as relishes poured<br />

over porridge. Forde and Scott (1946) report use of wild plants by the<br />

Hausa and note important contributions by the shea butternut tree and various<br />

locust trees, with additional contributions from baobab and the leaves of<br />

wild ebony. While Forde and Scott mention that 13% of the foods used by the<br />

Hausa are from wild resources, they provide no additional details. Vermeer<br />

(1979), commenting on the Tiv, identified an experimental agricultural system<br />

whereby wild foods are planted and tended along with domesticated plants in<br />

household gardens, specifically Amaranthus tricolor, Gynandropsis gynandra,<br />

22.

and Solanum indicum. The most important food-dietary reports from Nigeria,<br />

however, were produced by Bascom (1951a; 1951b) but while mentioning use of<br />

edible wild plants, he provides only vernacular terms.<br />

Cameroons<br />

An account by Malzy (1954) identified the basic botanical resources<br />

of Cameroons, while de Garine (1980), working among the Massa and Mussey<br />

peoples, provides dietary information -- but only passing reference to dietary<br />

utilization of wild plants as food.<br />

Zaire (Congo)<br />

Baxter and Bush (1953, p. 44), working among the Azande, identified<br />

dietary use of wild grasses, fruits, leafy vegetables, and roots and edible<br />

mushrooms, especially during the period immediately preceeding harvest. Bokoam<br />

and Droogers (1975) provide a basic ethnobotanical listing of more than 100<br />

plants used by the Wagenia for housing, food, fishing, medicine, and ritual.<br />

Reports by Thoen et al. (1973) and Parent and Thoen (1977) identify more than<br />

twenty species of edible mushrooms, noting that more than 20 tons of these<br />

products are consumed annually within Zaire (Table 14).<br />

23.

TABLES 8 - 14 FOLLOW<br />

TEXT RESUMES ON PAGE 35<br />

23a.

TABLE 8. Supplementary and Emergency Wild Food Plants of West Africa<br />

Latin Terminology<br />

RHIZOMES, ROOTS AND AERIAL TUBERS<br />

Dioscorea macroura<br />

Dioscorea preussii<br />

Dioscorea smilacifolia<br />

Dioscorea dumetorum<br />

Dioscorea hirtiflora<br />

Dioscorea minutiflora<br />

Dioscorea bulbifera<br />

Dioscorea bulbifera anthropophagorum<br />

Nymphaea lotus<br />

Boscia salicifolia<br />

Eriosema cordifolium<br />

Psophocarpus palustris<br />

Vigna vexillata<br />

Asclepias lineolata<br />

Raphionacme brownii<br />

Cryptolepis nigritana<br />

Ceropegia spp.<br />

Brachystelma bngeri<br />

Adansonia digitata<br />

Tacca involucrata<br />

Canna bidentata<br />

Trochomeria dalzielii<br />

Gladiolus quartinianus<br />

Gladiolus unguiculatus<br />

Gladiolus klattianus<br />

Solenostemon ocymoides<br />

Coleus dysentericus<br />

Ipomoea aquatica<br />

Dissotis grandiflora<br />

Icacina senegalensis<br />

Smilax kraussiana<br />

Orchis spp.<br />

Eulophia spp.<br />

Stylochiton warneckei<br />

Anchomanes difformis<br />

Amorphophallus dracontioides<br />

Amorphophallus aphyllus<br />

Cyperus esculentus<br />

Kyllinga erecta<br />

Mariscus umbellatus<br />

Thonningia spp.<br />

Carissa edulis<br />

Combretum spp.<br />

Dissotis spp.<br />

Hippocratea spp.<br />

24.

LATIN TERMINOLOGY<br />

TABLE 8 (CONTINUED)<br />

RHIZOMES, ROOTS AND AERIAL TUBERS (CONTINUED)<br />

BARK<br />

PITH<br />

BUDS<br />

Zygotritonia crocea<br />

Typha australis<br />

Craterispermum cerinanthum<br />

Bridelia ferruginea<br />

Bridelia micrantha<br />

Napoleona leonesis<br />

Boscia angustifolia<br />

Cadaba farinosa<br />

Ficus ovata<br />

Anogeissus schimperi<br />

Grewia mollis<br />

Adansonia digitata<br />

Acacia spp.<br />

Aristida stapoides<br />

Typha australis<br />

Borassus spp.<br />

Calamus deeratus<br />

Elaeis guineensis<br />

Cocos nucifera<br />

Hyphaene thebaica<br />

Phoenix reclinata<br />

Ancistrophyllum secundiflorum<br />

GUMS OR RESINS<br />

Acacia senegal<br />

Anogeissus schimperi<br />

Balanites spp.<br />

Sterculia setigera<br />

Sterculia cinera<br />

Lannea acida<br />

Acacia macrostachya<br />

SAP OR LATEX<br />

Calotropis procera<br />

Tetracera potatoria<br />

Sterculia setigera<br />

Gymnema sylvestre<br />

25.

STEMS<br />

TABLE 8 (CONTINUED)<br />

Euphorbia balsamifera<br />

Hymenocardia acida<br />

Borassus spp.<br />

Carica papaya<br />

Ehinochloa stagnina<br />

Ancistrophyllum secundiflorum<br />

Pergularia tomentosa<br />

Asparagus pauli-guilelmi<br />

Veronia amygdalina<br />

LEAVES (ore than 150 species regularly used as food; 25 semi-cultivated, 100 wild)<br />

FLOWERS<br />

Sesuvium portulacastrum<br />

Ancistrophyllum secundiflorum<br />

Stylochiton warneckei<br />

Momordica balsamina<br />

Tribulus terrestris<br />

Cassia tora<br />

Urera mannii<br />

Fleurya spp.<br />

Adansonia digitata<br />

Lippia adoensis<br />

Hyptis suaveolens<br />

Napoleona spp.<br />

Salvadora persica<br />

Grewia mollis<br />

Balanites spp.<br />

Parkia spp.<br />

Crotalaria glauca<br />

Tamarindus spp.<br />

Acacia spp.<br />

Sesbania aegyptiaca<br />

Sesbania grandiflora<br />

Sphenostylis schweinfurthi<br />

Bombax buonopozense<br />

Hibiscus sabdariffa<br />

Nymphaea lotus<br />

Leptadenia lancifolia<br />

Aloe barteri<br />

Taccazea barteri<br />

Taccazea nigritana<br />

Taccazea spiculata var. benedicta<br />

Cocculus pendulus<br />

Glossonema nubicum<br />

Tylostemon mannii<br />

26.

FLOWERS (CONTINUED)<br />

FRUITS<br />

SEEDS<br />

Anona senegalensis<br />

Lecaniodiscus cupanioides<br />

Typha australis<br />

Spilanthes acmella<br />

TABLE 8 (CONTINUED)<br />

Ochrocarpus africanus<br />

Hyphaene thebaica<br />

Zizyphus jujuba (Rhamnus lotus)<br />

Zizyphus spina-christi<br />

Sorindeia juglandifolia<br />

Uapaca esculenta<br />

Antrocaryon micraster<br />

Spondias monbin<br />

Cordyla africana<br />

Sarcocephalus esculentus<br />

Carissa edulis<br />

Anona senegalensis<br />

Cucumis anguria<br />

Lagenaria vulgaris<br />

Luffa acutangula<br />

Luffa cylindrica<br />

Momordica charantia<br />

Anacardium occidentale<br />

Lepidium sativum<br />

Anacardium occidentale<br />

Capsicum frutescens<br />

Capsicum annuum<br />

Lepidium sativum silvestre<br />

Trapa bispinosa<br />

Sesamum alatum<br />

Ceratotheca sesamoides<br />

CucumiL melo var. agrestis<br />

Parkia spp.<br />

Balanites aegyptiaca<br />

Cassia occidentalis<br />

Cassia tora<br />

Zizyphus mucronata<br />

Feretia apodanthera<br />

Tricalysia coffeoides<br />

Parkia biglobosa<br />

Abutilon spp.<br />

Entada gigas<br />

Boscia senegalensis<br />

Coffea maclaudii<br />

Coffea excelsa<br />

Coffea brevipes<br />

27.

SEEDS (CONTINUED)<br />

FUNGI<br />

FERNS<br />

Oryza barthii<br />

Oryza stapfii<br />

Panicum turgidum<br />

Panicum laetum<br />

Saccolepis africana<br />

Volvaria volvacea<br />

Volvaria esculenta<br />

Puccinia caricis<br />

Pteris aquilina<br />

SOURCE: Irvine (1952, pp. 23-40)<br />

TABLE 8 (CONTINUED)<br />

28.

TABLE 9. Edible Semi-Cultivated Leaves of West Africa<br />

Latir Terminology<br />

Lactuca taraxacifolia<br />

Justicia insularis<br />

Talinum triangulare<br />

Solenostemon ocymoides<br />

Sesamum radiatum<br />

Solanum nodiflorum<br />

Justicia insularis<br />

Justicia melampyrum<br />

Hibiscus abelmoschus<br />

Hibiscus cannabinus<br />

Gynura cernua<br />

Gynandropsis gynandra<br />

Cleome spp.<br />

Balanites aegyptiaca<br />

Corchorus acutangulus<br />

Ceratotheca sesamoides<br />

Celosia argentea<br />

Celosia laxa<br />

Celosia trigyna<br />

Amaranthus blitum<br />

Amaranthus graecizans<br />

Amaranthus viridus<br />

Vitex doniana<br />

Peperomia pellucida<br />

Amaranthus hybridus cruentus<br />

Corchorus acutangulus<br />

Solanum macrocarpum<br />

Gynura cernua<br />

Lactuca taraxacifolia<br />

Parkia oliveri<br />

Aframomum granum-paradisi<br />

Senecio biafrae<br />

Ceratotheca sesamoides<br />

Veronia amygdaliana<br />

Vernonia colorata<br />

SOURCE: Irvine (1956, pp. 35-41)<br />

Use<br />

Salad<br />

Salad<br />

Salad; pot-herb<br />

Tuber; pot-herb<br />

Leaves; seed<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Salad; pot-herb<br />

Vegetable<br />

Leaves; shoots; soup plant<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Soup; sauce<br />

Salad; pot-herb<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf; nut<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Leaves; soup<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Soup; sauce<br />

Soup; sauce<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Leaf; fruit<br />

Vegetable<br />

Leaf<br />

Pot-herb<br />

Leaves; fruits<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

Leaf<br />

29.

TABLE 10. Edible Wild Plants from Bamako, Mali<br />

Latin Terminology<br />

Adansonia digitata<br />

Aframomum melegueta<br />

Amaranthus cruentus<br />

Amaranthus viridis<br />

Andropogon canaliculatus<br />

Andropogon gayanus<br />

Andropogon pinginpes<br />

Andropogon pseudapricus<br />

Andropogon tectorum<br />

Boerhaavia diffusa<br />

Boerhaavia erecta<br />

Borassus aethiopium<br />

Burkea africana<br />

Canavalia virosa<br />

Canthium acutiflorum<br />

Cola nitida<br />

Camellia thea var. bokea<br />

Commiphora pedunculata<br />

Cymbopogon citratus<br />

Cymbopogon giganteus<br />

Cyperus articulatus<br />

Cyperus esculentus<br />

Digitaria exilis<br />

Dioscorea cayennensis<br />

Fagara xanthoxyloides<br />

Hibiscus esculentus<br />

Hibiscus sabdariffa<br />

Hyphaene thebaica<br />

Lippia chevalieri<br />

Loeseneriella africana<br />

Mentha spp.<br />

Oryza glaberrima<br />

Parkia biglobosa<br />

Pennisetum gambiense<br />

Phoenix dactylifera<br />

Portulaca oleracea<br />

Solanum aethiopicum<br />

Solanum lycopersicum<br />

Solanum melongena<br />

Solanum tuberosum<br />

Xylopia aethiopica<br />

Ziziphus mauritiana<br />

SOURCE: Diarra (1977, pp. 42-49).<br />

30.

TABLE 11. Nutritive Value of Some Ghanaian Edible Wild Plants<br />

LATIN PROTEIN Ca Fe<br />

TERMINOLOGY<br />

Voandzeia subterranea 19.7 108 195 9.7<br />

Psophocarpus tetragonolobus 31.2 210 410 15.0<br />

Coleus dysentericus 1.9 80 '90 2.0<br />

Cyperus esculentus 3.0 9 195 5.5<br />

Adansonia digitata 11.5 300 350 10.5<br />

Ceratotheca sesamoides 14.8 776 415 32.0<br />

Hibiscus cannabinus 17.6 280 550 18.0<br />

Cola acuminata 3.6 35 68 3.0<br />

Elaeis guineensis 6.5 71 195 6.0<br />

Butyrospermum parkii 6.0 10 124 3.8<br />

Ceiba spp. 20.4 310 640 10.0<br />

Amaranthus spp. 4.4 230 55 5.0<br />

Adasonia digitata (leaf) 11.5 2210 235 15.0<br />

Solanum spp. 1.1 8 30 1.0<br />

Portulaca oleracea 1.4 52 15 0.5<br />

Hibiscus sabdariffa (flower) 3.6 1176 160 14.2<br />

Bombax buonopoense (flower) 8.0 1670 152 7.0<br />

Monodora myrisitica 12.8 43 300 6.3<br />

SOURCE: Watson (1971, pp. 98-109)<br />

31.

TABLE 12. Indigenous Wild Edible Plants of Nigeria<br />

Latin Terminology<br />

Dioscorea praehensilis<br />

Dioscorea smilacifolia<br />

Dioscorea hirtiflora<br />

Dioscorea preussii<br />

Colocasia esculenta<br />

Amorphophallus dracontioides<br />

Treculia africana<br />

Musanga cercopioides<br />

Raphia vinifera<br />

Telfairia occidentalis<br />

Digitaria debilis<br />

Digitaria exilis<br />

Paspalum scrobiculatum<br />

Cenchrus biflorus<br />

Eleusine indica<br />

Oryza glaberrima<br />

Panicum spp.<br />

Eragrostis cilianensis<br />

Pennistum purpureum<br />

Elaeis guineensis<br />

Pentaclethra macrophylla<br />

Sphenostylis stenocarpa<br />

Voundzeia subterranea<br />

Mucuna urens<br />

Chrysophyllum africanum<br />

Irvingia gabonensis<br />

Pachylobus edulis<br />

Dennettia tripetala<br />

Uapaca guineensis<br />

Spondias monbin<br />

Landophia owarriensis<br />

Cyperus esculentus<br />

Tetracarpidium conorphorum<br />

Telfaria occidentalis<br />

Talinum trianrilare<br />

Amaranthus caudatus<br />

Celosia argentea<br />

Hibiscus esculentus<br />

Solanum torvum<br />

SOURCE: Okiy (1960, pp. 118-121)<br />

32.

TABLE 13. Edible Wild Plants, Benin, Nigeria<br />

Latin Terminology English Bini Terminology<br />

Aframomum melegueta Alligator pepper ehie ado<br />

Buchholzia coriacea owi<br />

Chrysophyllum africanum Apo otien<br />

Cola nitida Kola evbe<br />

Cucumeropsis edulis Egusi ogi<br />

Dacryodes (Pachylobus)<br />

edulis Native pear orumu<br />

Desplatzia subericarpa oghia wogha<br />

Dissotis rotundifolia ebafo<br />

Elaeis guineensis Oil palm udi<br />

Hibiscus esculentus Okora ikhievbo<br />

Irvingia gabonensis African Mango ogwi<br />

Plentaclethra Oil bean okpagha<br />

Piper guineense Benin pepper akboko<br />

Telfairia occidentalis Oyster nut umwenkhen<br />

Tetracarpidum conophorum African walnut okhue<br />

Thaumatococcus danielli abieba<br />

Uvaria chamae Yellow fever root agio<br />

Vernonia amygdalina Bitter leaf oriwo<br />

Xylopia ethiopica Guinea pepper unien<br />

Indigenous leaves:<br />

Amaranthus hybridus<br />

Talinum triangulare<br />

SOURCE: Johnson and Johnson (1976, pp. 376-377, 379).<br />

33.

TABLE 14. Nutritional Value of Edible Mushrooms, Upper-Shaba, Zaire<br />

Latin Terminology Protein Caloric Ca P Fe<br />

Value<br />

Amanita aff. aurea 16.0 295 180 630 450<br />

Amanita loosii 30.6 319 570 650 980<br />

Amanita cf. robusta 19.0 315 160 1325 500<br />

Cantharellus cibarius var.<br />

latifolius 14.5 300 148 707 1368<br />

Cantharellus congolensis 2.2 321 110 1050 8250<br />

Cantharellus luteopunctatus 21.4 313 475 700 990<br />

Cantharellus platyphyllus 22.6 319 127 713 978<br />

Cautharellus cf. ruber 25.5 256 424 711 1050<br />

Cantharellus sp. 10.8 305 210 800 1800<br />

Russula sp. 28.8 314 293 620 3140<br />

Lactarius latifolius 8.4 328 310 430 1000<br />

Lactarius cf. latifolius 3,.0 300 157 1044 1334<br />

Lactarius cf. inversus 11.9 325 800 350 2400<br />

Lactarius sp. 34.0 303 532 880 380<br />

Schizophyllum commune 17.0 315 90 646 280<br />

Termitomyces letestui 45.0 277 900 1130 390<br />

Termitomyces microcarp. 33.4 261 200 940 730<br />

Termitomyces sp. 41.0 279 517 460 650<br />

Termitomyces schiw;eri 37.3 285 400 870 266<br />

Termitomyces striatus f.<br />

urantiacus 4.0 290 165 1100 5600<br />

SOURCE: Parent and Thoen (1977, p. 443)<br />

34.

East Africa: General<br />

General introduction to nutrition and traditional agriculture in East<br />

Africa may be obtained from Culwick and Culwick (1941). One primary nutri<br />

tional topic associated with edible wild plants is the protein concentration<br />

of wild seeds and leaves as reported by Fowden and Wolfe (1957). More recent<br />

work on protein from wild plant resources has been conducted by Imbamba (1973)<br />

who noted values for 19 species, with special attention to the leaf protein<br />

contentration (LPC) for Crotolaria brevidens, Gynandropsis gynandra, and<br />

Solanum tuberosm -- all with values exceeding 30%. Olatumbosum (1976) also<br />

working on leaf protein content of wild greens, identified high values for<br />

Amaranthus caudatus, Celosia argentia, Solanum incanumi and Solanum modiflorum,<br />

noting that LPC from these species could easily be incorporated into field<br />

trials to improve diet where green leaves already were widely accepted as<br />

human food.<br />

East Africa: Botanical/Dietary Data by State<br />

Chad-Sudan-Ethiopia-Somaliland<br />

The transition zone between the arid Sahara and arid East Africa<br />

and the lush vegetation zones of "sub-Saharan Africa" are not a focal effort<br />

of this report. Nevertheless, a number of significant accounts deal with<br />

human utilization of edible wild plants that provide important data to the<br />

central question of this report. Tubiana and Tubiana (1977, pp. 13-29) re<br />

port an extensive list of edible wild plants used by the Zaghawa inhabiting<br />

the zone between Chad and the Republic of the Sudan (Table 15). Lewis (1969,<br />

pp. 74, 169), describing nomadic populations of Somalia, Afar, and Saho,<br />

briefly comments on the role wild edible fruits play in the dietary of no<br />

madic pastoralists. Huntingford (1953, pp. 61, 108) noted use of wild plants<br />

35.

y the Mondari Baronga, near Tali, northwest of Juba in the Sudan, while<br />

Corkill (1948) may be cited as an important early reference that wild plant<br />

use is not without danger, as seen in his report on Dioscorea dumetorum, a<br />

traditional famine food common to the Sudan.<br />

It is Ethiopia, however, that has attracted the most botanical and nutri<br />

tional attention. The Interdepartmental Committee on Nutrition for National<br />

Defense (ICNND, 1959) completed the initial nutritional survey of E.hiopia<br />

while Schaefer (1961) and Selinus (1968-1971, pp. 3-12) have identified the<br />

common dietary elements throughout Ethiopia. Such data, augmented by publi<br />

cation of extensive food composition tables for use in Ethiopia by Agren (1969),<br />

havepermitted research to continue on numerous important topics, for example<br />

the work by Selinus (1970) on preparation of home-made weaning foods prepared<br />

from both domesticated and wild food resources available locally. But perhaps<br />

the most intriguing report on nutrition to emerge from Ethiopia is the classic<br />

report by Knutsson and Selinus (1970) outlining cultural and historical problems<br />

of maintaining adequate nutritional quality under severe conditions of fasting<br />

as required by Ethiopian Coptic ritual.<br />

Huntingford (1969, p. 28), writing on the Galla, mentions widespread use<br />

of edible wild plants and provides documentation tor three; Rhamnus prinoides,<br />

Rhamnus tsaddo, and Vernonia amygdalina. Kloos (1976) completed a detailed<br />

examination of medicinal and dietary plants present in the rural markets of<br />

central Ethiopia, while Simoons (1965) reported cultivation of the wild plant<br />

Rhamnus prinoides (gesho) used in the preparation of Ethiopian fermented<br />

beverages. Lemordant (1971) reported comm consumption of four wild plants<br />

in Ethiopia .Balanites aegyptiaca, Carissa edulis, Rhamnus prinoides, and<br />

Rhamnus staddo), while Getahum (1974) identified more than one hundred widely<br />

36.

consumed wild plants (Appendix 4) noting general utilization increases with<br />

onset of the dry season between February and May. Getahum also comments on<br />

what he sees as a critical problem emerging in Ethiopia, loss of plant know<br />

ledge by the young. Miege and Marie-Noelle (1978) present data on Cordeauxia<br />

edulis, an arid zone species widely consumed in Ethiopia, whose seeds have<br />

a very favorable amino acid balance. They note that extinction of this plant<br />

would be an irreplaceable loss for the food supply of some East African peoples.<br />

Examination and review of the recent droughts experienced by Ethiopia<br />

is not within the scope of this report. Nevertheless, it is important to note<br />

that Ethiopian societies had generally been able to cope with the stress of<br />

drought by utilization of edible wild plants. Turton (1977) worked among the<br />

Mursi of southwestern Ethiopia and examined their response to drought. He<br />

found that prior to 1973 the Mursi had always been able to fall back upon wild<br />

bush foods as dietary staples when their domesticated field crops failed during<br />

drought. He reports that the increased severity of the drought in 1973, coupled<br />

with loss of knowledge relative to which plants were suitable for consumption, led<br />

to deprivation, malnutrition, and famine in a society that formerly had been able<br />

to cope well under drought conditions.<br />

Uganda<br />

Agricultural and food production systems for Uganda have been reported<br />

by Amann et al. (1972), building on research conducted by agronomists, physicians,<br />

and social scientists of preceeding decades. Relatively little work has been<br />

produced on the nutritional composition of Ugandan foodstuffs, although Jameson<br />

(1958) has produced tables of protein content of subsistence foods (primarily<br />

domesticated). Two reports, however, are central co understanding the dietary<br />

utilization of edible wild plants in Uganda. The first by Bennet et al. (1965)<br />

37.

is an overview of dietary practices of traditional Bantu Ganda, noting that<br />

eighteen unidentified "wild leaves" are common along with seven species of<br />

mushrooms. The second, by Tallantire and Goode (1975), is a recent monograph<br />

examining wild plants (many utilized as food) of West Nile and Madi districts,<br />

especially species whose leaves and fruits are used to supplement domesticated<br />

staples (Table 16). Tallantire and Goode comment severely on the loss of<br />

knowledge relative to edible wild plants in recent times and they note with<br />

concern that more and more of the important dietary supplements will be elimin<br />

ated from diet by traditional Ugandans who will no longer be able to identify<br />

such potential foods.<br />

Kenya<br />

Gerlach (1961; 1964; 1965) has presented a series of excellent publi<br />

cations on diet, food habits, and nutritional characteristics of Bantu peoples<br />

occupying the coastal regions of north-central Kenya but the classic work on<br />

food and nutrition in Kenya must stem from Boyd-Orr and Gilks (1913) in their<br />

important examination of diet and health comparing the Masai (a regimen based<br />

on flesh foods) and the Kukuyu (diet based on vegetable foods). Important re<br />

cent work on nutrition and wild plants has been completed by Taylor (1970)<br />

who investigated diet of the Kikuyu, noting important roles for Chenopodium<br />

opulifolium and Maranta arundinacea as the principal wild plants used. Taylor<br />

(p. 343) noted with concern that the development and expansion of agriculture<br />

has led to a significant decline in the dietary utilization of indigenous wild<br />

plants, with resulting decreased nutritional values in humans for vitamins A,<br />

B-complex, C, and the minerals calcium, iron, and phosphorus.<br />

Huntingford (1969, p. 59), writing on the Dorobo of the Kenya Highlands,<br />

states that wild foods include Rubus rigidus, Ximenia americana, wild forms of<br />

38.

Musa enset, with widespread consumption of miscellaneous resions and leaves<br />

that are gathered regularly for food. He also notes (p. 23) that the Nandi<br />

of the Uasin-Gisho Plateau, west of the Rift valley, regularly use wild<br />

vegetable leaf relishes, specifically Kigelia aethiopica, and that they fer<br />

ment the juice of the wild date palm (Phoenix reclinata). Huntingford (1969,<br />

p. 43) also wr..res on the Kipsigis of the Mau forest and Kisii Highlands, stat<br />

ing that wild vegetables and leaves are used, but he does not identify them by<br />

species.<br />

Glover et al. (1966), building on the work of Boyd-Orr and Gilks cited<br />

earlier, has presented a recent view of Masai diet in comparison with patterns<br />

exh 4 .bited by the related Kipsigis, noting extensive utilization of wild plants<br />

as food (Table 17). McMaster (1969, pp. 204-263), writing on the pastoral<br />

Turkana, noted utilization of Amaranthus spp. used regularly as dietary re<br />

lishes. Wagner (1970, pp. 59-60), working with the Logoli and Vugusu of<br />

Kavirondo district, noted that they rely on wild plants in the manufacture<br />

of local salts for human consumption and that wild fruits and mushrooms (not<br />

identified by species) are frequently collected. Gulliver and Gulliver (1968,<br />

pp. 34-35), worked among the Jie and identified wild greens as an important<br />

dietary element during the lean food months just before harvest. Weiss (1979)<br />

presents a general review of ed-ible wild plants utilized by coastal fishermen<br />

throughout Kenya (Table 18).<br />

Tanzania (Tanganyika; Zanzibar)<br />

Early research on nutrition and diet in Tanzania (Tanganyika, Zanzibar<br />

or both) stems from Smith and Smith (1935) and Culwick and Culwick (1939) with<br />

important contributions by Latham and Stare (1967), and the re<br />

cent investigations by Kreysler and Mndeme (1975). Such work, coupled with re<br />

39.

gional informaton on the nutritional composition of foods by Raymond (1941),<br />

provides background to important work completed on ethnic studies and the<br />

role of wild plants in maintaining quality nutrition.<br />

Glegg (1945), writing on the Sukuma, identified forty-six species<br />

with important dietary use (Table 19), yet Abrahams (1967, p. 33) made only<br />

brief comment that Sukuma females gather mushrooms and leaves from numerous<br />

wild plants. -ukui (1969), working. with the agro-pastoral Iraqw, identified<br />

five wild plants with important dietary roles, specifically Acalypha grantii,<br />

Coieus oguatics, Erucastrum arabicum, Ranunculus multifidus, and Solanum<br />

nigrum. Fleuret (1979a; 1979b), reporting on edible wild plants in Shamba<br />

diet in the vicinity of Lushoto, noted extensive, important roles for wild<br />

plants providing for high intakes of plant protein, carotene, calcium, and<br />

iron. Of equal important was her finding that Shamba women were able to<br />

sell wild plants, thus providing cash income to the sophisticated, energetic<br />

gatherer (Table 20).<br />

Wilson (1978), working on wild kenaf species (Hibiscus spp.) as commonly<br />

encountered in Kenya and Tanzania, documented dietery use of Hibiscus sabdariffa<br />

leaves and flowers.<br />

40.

TABLES 15 - 20 FOLLOW<br />

TEXT RESUMES ON PAGE 51<br />

40a.

TABLE 15. Edible Wild Plants of the Zaghawa, Sudan and Chad<br />

Latin Terminology Zaghawa Terminology<br />

Dactyloctenium aegyptiacum Absabe; bou; kreb<br />

Eragrostis pilosa Am-hoy; kwoinkwoin<br />

Pennisetum tiphoideum Bonu; bolu; bini<br />

Oryza breviligulata Am-belele; tomso<br />

Cenchrus biflorus Askanit; nogo<br />

Tribulus terrestris Drese; tara<br />

Grewia villosa Tomur el abid; korfu<br />

Grewia populifolia Giddem; nari<br />

Grewia flavescens Kabayna; gugur<br />

??? Baxshem; sono<br />

Ziziphus mauritiana Korno; kie<br />

Ziziphus spina-christi Nabak; kabara<br />

Balanites aegyptiaca Hejlij; gie<br />

Sclerocarya birroea Himed; gene<br />

Boscia senegalensis Moxet; madi<br />

Capparis decidua Tumtum; tundub; namar<br />

Maerua crassifolia Kurmut; nur<br />

Cordia rothii Andarab; turu<br />

Commiphora africana Gafal; togoria<br />

Cyperus rotundus tuberosus Siget; nogu<br />

Salvadora persica Shao; ui<br />

Colocynthis citrullus Battikh; oru<br />

Colocynthis vulgaris ???<br />

Coccinia grandis Tudu<br />

Hibiscus sabdariffa Karkan; anara; kerkere<br />

SOURCE: Tubiana and Tubiana (1977, pp. 14-25)<br />

41.

TABLE 16. Indigenous Edible Wild Plants, West Nile and Madi Districts, Uganda<br />

Latin Terminology Portion Used<br />

Nymphaea lotus root<br />

Cleome monophylla leaf<br />

Gyandropsis gynandra leaf<br />

Portulaca oleracea leaf<br />

Portulaca quadrifida leaf<br />

Amaranthus dubiu., leaf<br />

Amaranthus graecizans leaf<br />

Amaranthus hybridus hybridus leaf; seed<br />

La-enaria siceraria leaf; fruit<br />

Corchorus ol!torius leaf<br />

Corchorus tridLns leaf<br />

Corchorus trilocularis leaf<br />

Hibiscus surattenis leaf<br />

Sida alba leaf<br />

Acalypha bipart.ta leaf<br />

Acalypha ciliara leaf<br />

Acalypha racemasa leaf<br />

Micrococca mercurialis leaf<br />

Cassia obtusfolia leaf<br />

Tamarindus indica leaf; fruit<br />

Crotalaria brevidens var.<br />

intermeiia leaf<br />

Crotalar.a ochroleuca leaf<br />

Vigna urguiculata dekindtiana leaf<br />

Cyphosti:mma spp. leaf<br />

Leptaderia hastata leaf<br />

Aspilia pluriseta fruit<br />

Bidens piiisa leaf<br />

Crassocephaiim crepidioides leaf<br />

Crassocephalum rubens leaf<br />

Guizotia scabra fruit<br />

Capiscum frutescens leaf; fruit<br />

Solanum nigrum leaf<br />

Ipomoea eriocarpa leaf<br />

Sesamum angustifolium leaf<br />

Asystasia gangetica leaf<br />

Asystasia schimperi leaf<br />

Commelina benghalensis leaf<br />

Oxytenanthera abyssinica root<br />

Annona senegalensis fruit<br />

Syzygium guineense fruit<br />

Grewia mollis fruit<br />

Parinari curatellifolia fruit<br />

42.

TABLE 16 (CONTINUED)<br />

Latin Terminology Portion Used<br />

Afzelia africana fruit<br />