Inoculum 56(4) - Mycological Society of America

Inoculum 56(4) - Mycological Society of America

Inoculum 56(4) - Mycological Society of America

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Newsletter <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Mycological</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong><br />

— In This Issue —<br />

Fungal Cell Biology: Centerpiece<br />

for a New Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Microbiology in Mexico . . . 1<br />

Cordyceps Diversity<br />

in Korea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

MSA Business . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

Abstracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

<strong>Mycological</strong> News . . . . . . . . 68<br />

Mycologist’s Bookshelf . . . . 71<br />

<strong>Mycological</strong> Classifieds . . . . 74<br />

Mycology On-Line . . . . . . . . 75<br />

Calender <strong>of</strong> Events . . . . . . . 76<br />

Sustaining Members . . . . . . 78<br />

— Important Dates —<br />

August 15 Deadline:<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(5)<br />

July 23-28, 2005:<br />

International Union <strong>of</strong><br />

Microbiology Societies<br />

(Bacteriology and<br />

Applied Microbiology,<br />

Mycology, and Virology)<br />

July 30-August 5, 2005:<br />

MSA-MSJ, Hilo, HI<br />

August 15-19, 2005:<br />

International Congress on<br />

the Systematics<br />

and Ecology<br />

<strong>of</strong> Myxomycetes V<br />

Editor — Richard E. Baird<br />

Entomology and Plant Pathology Dept.<br />

Box 9655<br />

Mississippi State University<br />

Mississippi State, MS 39762<br />

Telephone: (662) 325-9661<br />

Fax: (662) 325-8955<br />

Email: rbaird@plantpath.msstate.edu<br />

MSA Homepage:<br />

http://msafungi.org<br />

Supplement to<br />

Mycologia<br />

Vol. <strong>56</strong>(4)<br />

August 2005<br />

Fungal Cell Biology: Centerpiece for a New<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Microbiology in Mexico<br />

By Meritxell Riquelme<br />

With a strong emphasis on Fungal Cell Biology, a new Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Microbiology was created at the Center for Scientific<br />

Research and Higher Education <strong>of</strong> Ensenada (CICESE) located<br />

in Ensenada, a small city in the northwest <strong>of</strong> Baja<br />

California, Mexico, 60 miles south <strong>of</strong> the Mexico-US border.<br />

Founded in 1973, CICESE is one <strong>of</strong> the most prestigious research<br />

centers in the country conducting basic and applied research<br />

and training both national and international graduate students<br />

in the areas <strong>of</strong> Earth Science, Applied Physics and<br />

Oceanology. Just 2 years ago a new Experimental and Applied<br />

Biology Division was created under the direction <strong>of</strong> Salomon<br />

Bartnicki-Garcia, who retired after 38 years as faculty member<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Plant Pathology at the University <strong>of</strong> California,<br />

Riverside and decided to move south to his country <strong>of</strong><br />

origin to create a Division in an area that was not developed at<br />

CICESE. The Experimental and Applied Biology Division is<br />

Continued on following page<br />

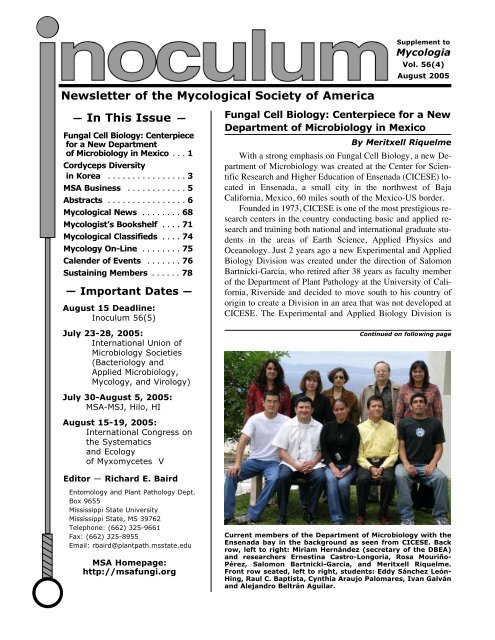

Current members <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Microbiology with the<br />

Ensenada bay in the background as seen from CICESE. Back<br />

row, left to right: Miriam Hernández (secretary <strong>of</strong> the DBEA)<br />

and researchers Ernestina Castro-Longoria, Rosa Mouriño-<br />

Pérez, Salomon Bartnicki-Garcia, and Meritxell Riquelme.<br />

Front row seated, left to right, students: Eddy Sánchez León-<br />

Hing, Raul C. Baptista, Cynthia Araujo Palomares, Ivan Galván<br />

and Alejandro Beltrán Aguilar.

Fungal foray in the Chichihuas forest (road from Ensenada<br />

to Tijuana) with UABC Mycology students during<br />

raining season (It does rain from time to time in<br />

Baja!).<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> 3 Departments (Microbiology, Marine<br />

Biotechnology and Conservation Biology).<br />

The Department <strong>of</strong> Microbiology gives an opportunity<br />

to young investigators to develop independent research<br />

projects under the unifying theme <strong>of</strong> Fungal Cell<br />

Biology. Although government funding for research in<br />

Mexico is less generous than in other countries, the Department<br />

is equipped to conduct both molecular studies<br />

and cell biology projects (video-microscopy, confocal<br />

microscopy and transmission electron microscopy) and<br />

is scheduled to move into a new building this year. An<br />

initial core <strong>of</strong> 4 researchers composes the Department:<br />

Salomon Bartnicki-Garcia (Mathematical and computer-assisted<br />

modeling <strong>of</strong> fungal growth), Rosa Mouriño-<br />

Perez (The fungal microtubular cytoskeleton), Ernestina<br />

Castro-Longoria (Cellular basis <strong>of</strong> the circadian<br />

a b<br />

2 <strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005<br />

rhythm in Neurospora) and Meritxell Riquelme (The<br />

secretory pathway in filamentous fungi).<br />

A major aim <strong>of</strong> the Department is to promote International<br />

Research Cooperation. The proximity to the<br />

US makes it practical to establish close links with US<br />

researchers. We already have ongoing projects with<br />

colleagues <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> California, Arizona<br />

State University, the University <strong>of</strong> Oregon and Massachusetts<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology. The Department has<br />

also established strong links with local institutions,<br />

such as the Autonomous University <strong>of</strong> Baja California<br />

(UABC) and the National Institute for Forest and Agricultural<br />

Research (INIFAP). We participate in undergraduate<br />

Mycology courses at the UABC.<br />

For further information and current openings<br />

please visit the websites www.cicese.mx and microbio.cicese.mx/.<br />

Immunolocalization<br />

<strong>of</strong> microtubules in a<br />

chemically fixed cell<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sclerotium rolfsii.<br />

(R. Mouriño-Pérez)<br />

Questions or comments should be sent to<br />

Meritxell Riquelme Pérez, Departamento de<br />

Microbiología, DBEA, CICESE, Km. 107 Carretera<br />

Tijuana-Ensenada, 22860 Ensenada,<br />

Baja Califo. Email: riquelme@cicese.mx<br />

Molecular tagging <strong>of</strong> proteins involved in<br />

hyphal growth and morphology with GFP.<br />

Laser scanning confocal micrographs <strong>of</strong><br />

growing hyphae <strong>of</strong> N. crassa with a) a fluorescent<br />

Spk; c) fluorescent plasma membrane.<br />

(M. Riquelme)

Cordyceps Diversity in Korea<br />

Cordyceps is traditionally known as a highly medicinal<br />

mushroom in oriental society <strong>of</strong> Asia. It is quite<br />

diverse in its morphological characters, host range, natural<br />

habitat, etc. Due to contrast climatic variation and<br />

its unique geographical position, Cordyceps diversity is<br />

rich in Korea. Research on Cordyceps <strong>of</strong> Korea during<br />

last 20 years has shown that some species are widely<br />

distributed, while others grow in specific locations.<br />

Maturation periods <strong>of</strong> stromata range from late spring to<br />

summer till early autumn every year. Most species<br />

show their host specificity, but few species grow in diverse<br />

hosts. Microscopically, Cordyceps species differ<br />

in their spore shape, size, and their conidiation nature.<br />

There are about 300-400 Cordyceps species all over<br />

the world and are distributed universally (Kobayasi,<br />

1982; Kobayasi and Shimizu, 1983; Sung, 1996).<br />

Species <strong>of</strong> Cordyceps (Clavicipitaceae, Hypocreales,<br />

Ascomycota) grow inside insect host bodies as endosclerotium<br />

during winter and produce stromata in summer.<br />

Hosts <strong>of</strong> Cordyceps species include different stages<br />

<strong>of</strong> insect life cycle ranging from larva to adult <strong>of</strong> different<br />

insect orders, bee, wasp, cicadae, beetle, etc., except<br />

few which grow on hypogeous Elaphomyces species.<br />

Their scientific study and cultivation have been done in<br />

Korea for a long time. Every year, entomopathogenic<br />

fungal specimens including Cordyceps species are collected<br />

from different parts <strong>of</strong> Korea and are air-dried and<br />

preserved along with their isolates in Entomopathogenic<br />

Fungal Culture Collection (EFCC), Kangwon National<br />

University, Korea (Sung, 2004). The specimens are<br />

identified on the basis <strong>of</strong> their morphological characters.<br />

By Jae-Mo Sung, Bhushan Shrestha, Sang-Kuk Han, Su-Young Kim,<br />

Young-Jin Park, Won-Ho Lee, Kwang-Yeol Jeong, Sung-Keun Choi<br />

Continued on following page<br />

Fig. 3. C. gracilis<br />

Fig. 1. C. militaris<br />

Fig. 2. C. bifusispora<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005 3

Fig. 4. C. longissima<br />

Cordyceps species are collected from different parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> Korea every year from early May to late October.<br />

Cordyceps species, such as C. militaris (Fig. 1), C. pruinosa<br />

and C. sphecocephala are frequently collected,<br />

while C. bifusispora (Fig. 2), C gracilis (Fig. 3), C. heteropoda,<br />

C. longissima (Fig. 4), C. nakazawai, C.<br />

ochraceostromata, C. pentatomi, C. ramosopulvinata<br />

(Fig. 5), C. rosea, C. scarabaeicola, C. staphylinidaecola<br />

and C. yakushimensis are moderate or rare in distribution.<br />

Ascospores are discharged from fresh specimens<br />

and observed for their morphology and germination by<br />

staining with cotton blue in Lactophenol. Ascospores are<br />

inoculated in nutrient agar media in test-tubes and incubated<br />

till pr<strong>of</strong>use mycelium growth occurs. Original isolates<br />

and their sub-cultures are preserved at 4C in Entomopathogenic<br />

Fungal Culture Collection (EFCC),<br />

Kangwon National University, South Korea. Specimens<br />

are air-dried and preserved in herbarium boxes.<br />

4 <strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005<br />

Fig. 5. C. ramosopulvinata<br />

It is very interesting to observe ascospore morphology<br />

and their germination behavior <strong>of</strong> different Cordyceps<br />

species. Among the observed species, only few<br />

such as C. bifusispora and C. pruinosa produced filamentous<br />

ascospores with threads in the center, while the<br />

remaining produced filamentous ascospores with continuous<br />

part-spores throughout the length. The germination<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> C. bifusispora, C. militaris, C. pentatomi, C.<br />

pruinosa, C. scaraebaeicola, C. staphylinidaecola were<br />

found faster, while those <strong>of</strong> C. gracilis, C. heteropoda,<br />

C. longissima, C. nakazawai, C. ochraceostromata, C.<br />

ramosopulvinata, C. rosea, C. sphecocephala, C.<br />

yakushimensis were found shower. Microscopic figures<br />

<strong>of</strong> ascospores are shown in sides <strong>of</strong> each figure <strong>of</strong> different<br />

Cordyceps species. C. militaris and C. pruinosa<br />

developed conidia on germinating hyphae soon, showing<br />

microcyclic conidiation character. Cordyceps isolates<br />

vary in their growth speed and cultural characteristics.<br />

Stromata <strong>of</strong> different Cordyceps species, such as<br />

C. militaris, C. scarabaeicola, C. pruinosa have been<br />

successfully produced in brown rice medium.<br />

References: Kobayasi, Y. 1941., Sci. Rept. Tokyo.<br />

Bunrika, Daigaku Sect. B. 5:53-260; Kobayasi, Y.<br />

1982. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan. 23:329-364; Kobayasi,<br />

Y. and D. Shimizu. 1983. Hoikusha Publishing Company<br />

Ltd. Osaka. 280 pp.; Sung, J.M. 1996. Kyo-Hak<br />

Publishing Co. Ltd., Seoul. 299 pp.; Sung, J.M. 2004.<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> 55(4):1-3.<br />

Questions or comments should be sent to<br />

Jae-Moe Sung, Entomopathogenic Fungal<br />

Culture Collection (EFCC), Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Applied Biology, Kangwon National University,<br />

Chuncheon 200-701, South Korea.<br />

Email: cordyceps@nate.com.

From the President’s Corner …<br />

Dear Friends and Colleagues,<br />

The success <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Mycological</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>America</strong> depends heavily<br />

on the volunteer contributions <strong>of</strong> its<br />

members. We are always looking for<br />

volunteers who would like to be involved<br />

in the various functions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

society, and there are many <strong>of</strong> them<br />

from annual meeting preparations to<br />

specialized committees on subdisciplines<br />

within mycology. The list <strong>of</strong><br />

committees is on the MSA website.<br />

We need to hear from you if you<br />

would like to participate in some<br />

MSA Secretary Email Express<br />

Council completed five email polls since my May report and<br />

approved the following:<br />

• Poll 2005-3. Editor-in-Chief Donald Natvig nominated<br />

Dr. Robby Roberson to serve as Mycologia Associate<br />

Editor for the term 2005-2007. Approved.<br />

• Poll 2005-5. It was moved by President McLaughlin and<br />

seconded by Secretary Murrin that Executive Council approve<br />

a further increase <strong>of</strong> $4000 for the MSA Student<br />

Mentor Travel Awards for Hilo, to be awarded from income<br />

from the Uncommitted Endowment Fund. Approved.<br />

Background: The MSA had previously allotted<br />

an increased amount for Student Mentor Travel Awards<br />

this year, from approximately $4000 to $10,000, based on<br />

the anticipated increased costs <strong>of</strong> travel for the Hilo meeting.<br />

The Mentor Travel Awards Committee received 38<br />

applications this year, which appears to be a record number.<br />

The increase approved here allowed for an additional<br />

5 students to be funded for a total <strong>of</strong> 18 students. MSA<br />

coordinated efforts with Deep Hypha, the NSF-funded<br />

Research Coordination Network (RCN), which also<br />

awarded travel funding for Hilo.<br />

• Polls 2005 6-8: Approved. These motions concerned the<br />

approval <strong>of</strong> the Honorary Member and MSA Fellows for<br />

2005 following recommendations by George Carroll,<br />

Chair <strong>of</strong> the Honorary Awards Committee, and one other<br />

special award. Due to the confidential nature <strong>of</strong> these decisions<br />

until they are announced at the Annual Business<br />

Meeting in Hilo, August 3rd , they will not be reported on<br />

fully until the next issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Inoculum</strong>.<br />

New Members: The MSA extends a warm welcome to all<br />

new (and returning) members. New memberships will be formally<br />

approved by the <strong>Society</strong> at the Annual Business Meeting<br />

in Hilo, Hawaii (Aug 3rd , 2005).<br />

• Australia: Susanna Ann Driessen, Kelli Maria Gowland<br />

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

BUSINESS<br />

way. Whether there is a topic in<br />

which you would especially like to<br />

be involved or whether you would<br />

just like to contribute in some way,<br />

please consider volunteering. Send<br />

and email or talk to me or Vice President<br />

James Anderson or Secretary<br />

Faye Murrin and let us know your<br />

interest. Participating on a <strong>Society</strong><br />

committee is a great way to get to<br />

know the society and even a small<br />

contribution <strong>of</strong> your time and energy<br />

will be very helpful to the <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

David J. McLaughlin,<br />

MSA President<br />

• Canada: Melissa Day<br />

• Ghana: Hubert D Nyarko<br />

• Hong Kong: Justin Bahl, Wing Yan Chum<br />

• Japan: Yuko Ota<br />

• Mexico: Cristina Medina<br />

• United States: Anabelle Aranda, Kelly D Craven, Jennifer<br />

M. Davidson, Joyce Eberhart, Javesh Garan,<br />

Michele Therese H<strong>of</strong>fman, Bradley Warren Miller, Anil<br />

Kumar H Raghavendra, Kim Ryall, Marian N Viveros,<br />

Sandra W Woolfolk<br />

Emeritus membership: There has been one new application<br />

for emeritus membership: L J Wickerham <strong>of</strong> Tucson,<br />

Arizona. Emeritus memberships will be formally approved<br />

by the <strong>Society</strong> at the Annual Business Meeting in Hilo,<br />

Hawaii (Aug 3 rd , 2005).<br />

Faye Murrin<br />

MSA Secretary<br />

fmurrin@mun.ca<br />

Canine Foray — Faye Murrin’s dog, Rosie, protects the<br />

catch from mushroom bandits.<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005 5

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

Aaltonen, Ronald E.*, Barrow, Jerry R., Lucero, Mary L., Osuna-Avila, Pedro<br />

and Reyes-Vera, Isaac. USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, Las Cruces,<br />

NM 88003, USA. jbarrow@nmsu.edu. The microscopic identification <strong>of</strong> vertically<br />

transferred symbiotic fungi intrinsically integrated with cells, tissues<br />

and organs <strong>of</strong> host plants.<br />

Dual staining methodology and analysis with light microscopy and scanning<br />

electron microscopy were used to determine the nature and extent <strong>of</strong> symbiotic<br />

fungi with native desert grasses shrubs. Trypan Blue that targets fungal chitin<br />

and sudan IV that targets lipid bodies attached to fungal structures were used to<br />

stain cleared roots and leaves. Trypan blue revealed a densely stained fungal network,<br />

bound to the plasmalema <strong>of</strong> meristematic cells, that were transferred to cells<br />

in culture, tissues and all plant organs. Fungal structures were atypical and were<br />

substantially different than commonly observed fungal structures such as hyphae,<br />

spores, etc. Fungal associations with meristem cells facilitate their distribution and<br />

vertical transfer to all parts <strong>of</strong> the plant, seed and to succeeding generations. Significant<br />

are fungal associations with vascular tissue, photosynthetic cells and with<br />

the stomatal complex and suggests significant plant-fungus interactions within<br />

these critical plant cells. poster<br />

Abdelzaher, Hani M. A. Faculty <strong>of</strong> Science, El-Minia University 61519, Egypt.<br />

abdelzaher@link.net. Biological control <strong>of</strong> damping-<strong>of</strong>f and root rot diseases<br />

<strong>of</strong> soybean caused by Pythium spinosum Sawada var. spinosum using three<br />

rhizosphere species <strong>of</strong> soil fungi.<br />

Pythium spinosum was isolated from rhizosphere soil and rhizoplane <strong>of</strong><br />

healthy and infected soybean roots cultivated in an agricultural field located in<br />

Shahean district, El-Minia city, Egypt in June 2003. Rhizosphere and rhizoplane<br />

myc<strong>of</strong>lora isolated from the same sites were tested for their antagonism toward<br />

Pythium spinosum in agar plates. Among the isolated fungi, Aspergillus sulphureus,<br />

Penicillium islandicum and Paecilomyces variotii were chosen according<br />

to their antagonism on agar plates for experimentation to test their effectiveness<br />

for biological control in either autoclaved or nonsterilized soil. Coating<br />

soybean seeds and roots with spores and mycelia <strong>of</strong> these three antagonists gave<br />

germinating seeds and seedlings a very good protection from root-rot, pre- and<br />

post-emergence damping-<strong>of</strong>f caused by P. spinosum. Applying these biocontrol<br />

agents to autoclaved and nonsterilized soil infested with P. spinosum provided an<br />

excellent way <strong>of</strong> protection. contributed presentation<br />

Abe, Jun-ichi P. University <strong>of</strong> Tsukuba, Graduate School <strong>of</strong> Life and Environmental<br />

Science, 1-1, Tennoudai 1 chome, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan. jave@sakura.cc.tsukuba.ac.jp.<br />

An arbuscular mycorrhizal genus in the Ericaceae.<br />

Enkianthus is an ericaceous genus with about 17 spp. <strong>of</strong> shrubs and small<br />

trees, commonly distributed in Japan and southern China. Four Japanese native<br />

species <strong>of</strong> the genus Enkianthus (E. campanulatus, E. cernuus f. rubens, E. perulatus,<br />

E. subsessilis) were examined to determine the mycorrhizal status by comparing<br />

with typical ericoid mycorrhizal roots <strong>of</strong> Rhododendron kaempferi. The<br />

roots <strong>of</strong> all species were collected from trees <strong>of</strong> natural stands or public gardens<br />

and from seedlings <strong>of</strong> E. cernuus f. rubens grown in controlled conditions. These<br />

roots were observed with a compound light microscope and SEM. All examined<br />

roots <strong>of</strong> Enkianthus spp. formed only arbuscular mycorrhiza <strong>of</strong> the Paris-type.<br />

The fine roots <strong>of</strong> these species were usually thicker (approx. 150 µm) than the hair<br />

roots <strong>of</strong> R. kaempferi (approx. 80 µm). Short root hair- like structures with thick<br />

walls (approx. 5 µm) were observed occasionally on the fine roots <strong>of</strong> all<br />

Enkianthus spp. and root hairs were observed in E. subsessilis. Consequently, the<br />

mycorrhizal and root morphology <strong>of</strong> these four species are completely different<br />

from R. kaempferi. This result reveals that at least these four species <strong>of</strong> Enkianthus<br />

seem to be arbuscular mycorrhizal and lack ericoid mycorrhiza. These findings<br />

and the mycorrhizal status <strong>of</strong> the ancient ericaceous species are discussed. contributed<br />

presentation<br />

Aime, M. Catherine. USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany &<br />

Mycology Lab, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA. cathie@nt.ars-grin.gov. Molecular<br />

systematics <strong>of</strong> Uredinales.<br />

Rust fungi (Basidiomycota, Uredinales) consist <strong>of</strong> > 7000 species <strong>of</strong> obligate<br />

plant pathogens that possess some <strong>of</strong> the most complex life cycles in the Eumycota.<br />

Traditionally, phylogenetic inference within the Uredinales has been<br />

hampered by a lack <strong>of</strong> morphological characters and incomplete life cycle and<br />

host-specificity data. The application <strong>of</strong> modern molecular characters to rust systematics<br />

has been limited by several factors, including, to name a few, the inability<br />

to pure culture most rusts or unequivocally separate rust from host cells and<br />

other associated fungi in a specimen. Previous molecular systematic studies <strong>of</strong><br />

rusts have focused on analyses <strong>of</strong> 28S or 18S ribosomal DNA, but current contradictions<br />

in rust systematics, especially in the deeper nodes, have not yet been<br />

resolved. In this study, several genes (including 18S, 28S, and EF1alpha) were examined<br />

across the breadth <strong>of</strong> the Uredinales to resolve systematic conflicts and<br />

provide a framework for the group. It is concluded that morphology alone is a<br />

poor predictor <strong>of</strong> rust relationships at most levels and strict morphology-based<br />

classifications and species-delimitations appear obsolete. Host selection, on the<br />

other hand, has played a significant role in rust evolution. The difficulties and utility<br />

<strong>of</strong> analyzing protein-coding genes vs. rDNA in rust systematics are also discussed.<br />

symposium presentation<br />

6 <strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005<br />

Aime, M. Catherine 1 * and Henkel, Terry W. 21 USDA-Agricultural Research Service,<br />

Systematic Botany & Mycology Lab, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA, 2 Humboldt<br />

State University, Dept. <strong>of</strong> Biological Sciences, Arcata, CA 95521, USA.<br />

cathie@nt.ars-grin.gov. Strategies for bioinventory: lessons from Guyana.<br />

Bioinventory, the identification and enumeration <strong>of</strong> taxa within a given<br />

area, provides the foundation for numerous biological and ecological studies. Yet<br />

fungal inventories are vastly underrepresented in the literature, and the conduction<br />

<strong>of</strong> such inventories presents a host <strong>of</strong> unique difficulties and problems. Special<br />

problems faced in conducting fungal inventories include deciding at which level<br />

to record units (e.g., fruiting bodies, cultures, and/or environmental sequences);<br />

how to construct significant sampling strategies (e.g. plot studies, transects, and/or<br />

sweeps); and, especially, how to conduct the alpha-taxonomy. We have completed<br />

five years <strong>of</strong> comparative plot studies for fungi in a remote, rain-forested region<br />

<strong>of</strong> west-central Guyana. To date we have documented nearly 1,000 species<br />

or morphospecies <strong>of</strong> macromycetes, both ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic, and<br />

counted >20,000 fruiting bodies. Yet the most time-consuming aspect <strong>of</strong> this<br />

study is the taxonomy. To date, we have been able to identify and publish less than<br />

10% <strong>of</strong> the Guyanese taxa; > 40% <strong>of</strong> these have been species or genera new to<br />

science. Some ideas for recording, analyzing, and identifying fungal taxa from<br />

previously under-sampled areas will be discussed. symposium presentation<br />

Akamatsu, Y. and Saikawa, Masatoshi*. Department <strong>of</strong> Environmental Science,<br />

Tokyo Gakugei University, Koganei-shi, Tokyo 184-8501, Japan. saikawa@ugakugei.ac.jp.<br />

Giant mycelium by Sommerstorffia spinosa.<br />

Since 1984, Sommerstorffia spinosa was obtained several times from samples<br />

<strong>of</strong> debris floating on the water <strong>of</strong> a fire reservoir located in the campus <strong>of</strong><br />

Tokyo Gakugei University. The species has been known as a rotifer-parasite, to<br />

have the ability to capture the animals with a peg, a distal narrow protuberance <strong>of</strong><br />

hypha, or to parasitize them with a bowling-pin shaped sporeling developed from<br />

an encysted, secondary zoospore. In all the strains reported up to now, each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

isolates finished capturing animals after 3 to 7 times <strong>of</strong> capture by the peg and became<br />

solely to produce zoospores. Thus the mycelium was quite limited in size in<br />

all cases. However, in spring, 2004, we obtained a strain <strong>of</strong> the species, the<br />

mycelium <strong>of</strong> which did not finish capturing rotifers (Lepadella oblonga) and grew<br />

unlimitedly to establish a giant mycelium. At 30 days <strong>of</strong> cultivation under water,<br />

it could be seen with a naked eye, because the size being 0.5-3.0 mm in diameter.<br />

The hyphae (7-9 µm wide) constituting the giant mycelium were empty except<br />

only their distal portion terminated with a peg (6-8 µm long, 3-5 µm wide). After<br />

capturing a rotifer, the peg grew into an endozoic thallus that developed one or<br />

two hyphae externally and transformed itself into a zoosporangium with an evacuation<br />

tube (50-80 µm long, 8-10 µm wide). The primary zoospores encysted at<br />

the mouth <strong>of</strong> the evacuation tube to form a mass <strong>of</strong> cysts (7-9 µm). In normal<br />

strains, each <strong>of</strong> the primary cysts soon produces a secondary zoospore, though the<br />

cyst <strong>of</strong> our strain did not produce it, but lost its content, or, in rare occasion, developed<br />

a sporeling (ca. 17 µm long, 8 µm wide). The giant mycelium <strong>of</strong> our<br />

strain also captured two testaceous rhizopods <strong>of</strong> Cryptodifflugia and Euglypha.<br />

contributed presentation<br />

Almeida-Leñero, Lucia 1 , Ludlow-Wiechers, Beatriz 1 , Geel, Bas van 2 , González,<br />

María C. 3 * and Aptroot, André. 4 1 Dept. Ecología y Rec. Nat, Fac. Ciencias,<br />

UNAM, Mexico DF 04510, 2 IBED, Paleoecology and Landscape Ecology, Univ.<br />

Amsterdam Kruislaan 318, 1098 SM Amsterdam The Netherlands, 3 Inst. Biología,<br />

UNAM, Mexico, 4 Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Fungal<br />

Biodiversity Centre, P.O. Box 85167, 3508 AD Utrecht, The Netherlands.<br />

mcgv@ibiologia.unam.mx. Records <strong>of</strong> mid-Holocene fungi from Lake Zempoala,<br />

Central Mexico.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> the present study is to describe and illustrate fungal spores<br />

recorded on Zempoala lake at 2800 m altitude. The studied interval is <strong>of</strong> mid-<br />

Holocene age. The lake with submerged aquatical and hydroseral shore vegetation,<br />

lie today in the Abies religiosa dominated forest belt. The samples were prepared<br />

using standard techniques for palynological studies. A number <strong>of</strong> selected<br />

fungal spores have been identified, described and illustrated. Ecological environmental<br />

preferences <strong>of</strong> present fungi are also given. Among the fungi type spores<br />

analysed are 2 basidiospores: Enthorriza (type 527), and Urocystis, 3 ascospores:<br />

Astrosphaeriella, Ustulina, Valsaria, and 10 mitospores: Acrodictys, Antennatula,<br />

Brachydesmiella, Endophragmiella, Monodictys, Trichocladium type 1 and 2,<br />

Papulospora, and Virgatospora. These fungus occur together with pollen elements<br />

that define a landscape <strong>of</strong> forest and a water body. Antennatula confirm an<br />

Abies sp. forest, Acrodictys suggests species <strong>of</strong> Populus sp., Virgatospora <strong>of</strong><br />

broad leaved tree forest, and Ustulina the presence <strong>of</strong> deciduous trees. Enthorriza,<br />

and Trichocladium are evidence <strong>of</strong> freshwater. Environment conditions may be<br />

presumed <strong>of</strong> high air humidity considering the presence <strong>of</strong> decaying plant debris<br />

and soil forming fungi such as Monodictys and Papulospora. The fungi were<br />

recorded for first time in paleoecological studies in Mexico. poster<br />

An, Zhiqiang. Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA, USA. Polyketide<br />

synthase genes in the pneumocandin-producing fungus Glarea lozoyensis.<br />

Glarea lozoyensis is the producer <strong>of</strong> pneumocandin B0, a potent inhibitor<br />

Continued on following page

<strong>of</strong> fungal glucan synthesis. This industrially important filamentous fungus is<br />

slow-growing, is very darkly pigmented, and has not been easy to manipulate genetically.<br />

Using a PCR strategy to survey the G. lozoyensis genome for secondary<br />

metabolic encoding pathways, we have identified three polyketide synthase<br />

genes: pks1, pks2, and pks3. pks1 encodes a 2,124 amino-acid protein with five<br />

catalytic modules: ketosynthase, acyltransferase, two acyl carrier sites, and<br />

thioesterase/Claisen cyclase. Pks2 encodes a 1,791 amino-acid protein with five<br />

catalytic modules: â-ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), dehydratase (DH),<br />

â-ketoacyl reductase (KR), and acyl carrier protein (ACP). The pks3 gene acts as<br />

an operon and encodes two enzymes, PKS3-NRPS1 and NRPS2. Cluster analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> 37 fungal ketosynthase modules grouped the pks1p with PKSs involved in<br />

1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis; the pks2p with PKSs involved<br />

in 6-methylsalicylic acid biosynthesis; and the pks3p was grouped with PKSs that<br />

synthesize structurally and bioactively complex polyketides. An Agrobacteriummediated<br />

transformation system was developed for the disruption <strong>of</strong> these three<br />

pks genes. Disruption <strong>of</strong> pks1 yielded knockout mutants that displayed an albino<br />

phenotype, suggesting that pks1 encodes a tetrahydroxynaphthalene synthase.<br />

Heterologous expression <strong>of</strong> pks2 in Aspergillus nidulans showed that pks2 encodes<br />

for 6-methylsalicylic acid synthase. Disruption <strong>of</strong> pks3 showed no difference<br />

in chemical pr<strong>of</strong>iles under the fermentation conditions used. Other genes reside<br />

in the three pks loci will also be discussed. symposium presentation<br />

Anagnost, Susan E. 1 *, Catranis, Catharine M. 2 , Fernando, Analie A. 1 , Morey,<br />

Shannon R. 1 , Zhou, Shuang 1 , Zhang, Lianjun 3 and Wang, C.J.K. 41 Wood Products<br />

Engineering, SUNY College <strong>of</strong> Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse,<br />

NY 13210, 2 <strong>America</strong>n Type Culture Collection, 10801 University Blvd.,<br />

Manassas, VA 20110 USA, 3 Forest and Natural Resources, SUNY-ESF, Syracuse,<br />

NY, 4 Faculty <strong>of</strong> Environmental and Forest Biology, SUNY-ESF, Syracuse<br />

NY 13210, USA. seanagno@esf.edu. Aeromycology <strong>of</strong> homes in Syracuse,<br />

New York.<br />

Airborne fungi were recovered at 103 homes in Syracuse, New York as part<br />

<strong>of</strong> an environmental survey <strong>of</strong> homes <strong>of</strong> infants predisposed to asthma (EPA project<br />

No. R-82860501-0). Total colony-forming units per cubic meter <strong>of</strong> air<br />

(CFU/m 3 ) and isolate identifications were obtained from samples collected with<br />

the Andersen N6 sampler. Samples collected on two consecutive days, indoors<br />

and outdoors, during 147 visits to these homes yielded 14<strong>56</strong>5 isolates that were<br />

classified into 170 fungal taxa. Among the most frequent were Hyaline unknowns,<br />

Cladosporium cladosporioidies, Penicillium spp., Aspergillus spp., basidiomycetes,<br />

Cladosporium herbarum, and Alternaria spp. Aspergillus spp were<br />

more frequent indoors (547 isolations) compared to outdoors (59 isolations), as<br />

were Penicillium spp (771 indoor, 137 outdoor). The total CFU/m3 was greater<br />

during the summer and fall seasons; certain species only appeared during summer<br />

and fall. Three new records for the USA were: Acrodontium myxomyceticola, 173<br />

isolates from 41 homes; Acremonium roseolum, 36 isolates from 18 homes; and<br />

Tetracoccosporium paxianum, once. A new sub-culturing method (Random-50)<br />

allowed the recovery <strong>of</strong> slow-growing, sometimes rare, fungi. These same Random-50<br />

plates can estimate with high confidence the total fungal concentration in<br />

these homes. poster<br />

Aoki, Takayuki 1 *, Tomomi, Tsunematsu 2 and Sato, Toyozo 3 . 1 Genetic Diversity<br />

Department, National Institute <strong>of</strong> Agrobiological Sciences, Kannondai, Tsukuba,<br />

Japan, 2 University <strong>of</strong> Tsukuba, Tennodai, Tsukuba, Japan, 3 Genebank, National<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Agrobiological Sciences, Kannondai, Tsukuba, Japan.<br />

taoki@nias.affrc.go.jp. Re-identification <strong>of</strong> Fusarium moniliforme isolates deposited<br />

at the MAFF Genebank, NIAS, Japan based on analysis <strong>of</strong> DNA sequences<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Histone H3 gene region.<br />

On a long used fungal name, Fusarium moniliforme, a recommendation to<br />

refrain its usage was issued by the ISPP/ICTF Subcommittee on Fusarium Systematics.<br />

This is because <strong>of</strong> the facts that: (1) the name, F. moniliforme represents<br />

an unacceptably broad species concept; and (2) F. verticillioides as mating population<br />

(MP) A <strong>of</strong> the Gibberella fujikuroi (GF) species complex is the older name<br />

for the species in strict sense. Microorganisms Section <strong>of</strong> the MAFF Genebank,<br />

NIAS, Japan has been preserving rather many number <strong>of</strong> strains identified previously<br />

as F. moniliforme for a distribution purpose. To respond to the recommendation,<br />

70 strains <strong>of</strong> F. moniliforme deposited at MAFF were re-identified based<br />

on the DNA sequences <strong>of</strong> the Histone H3 gene region. By using a PCR primerset,<br />

H3-1a and H3-1b, gene fragments <strong>of</strong> this region, ca. 520 bps, were amplified<br />

and sequenced. DNA sequences were aligned with Clustal X ver. 1.8 and phylogenetic<br />

analyses were made with PAUP ver. 4.0b10 by generating NJ and MP<br />

trees. Sequence data for the same gene region <strong>of</strong> related species <strong>of</strong> Fusarium were<br />

downloaded from the GenBank site, NCBI, and analyzed together. Out <strong>of</strong> 70<br />

strains examined, <strong>56</strong>, 7 and 4 strains were identified as F. fujikuroi (corresponding<br />

to the MP-C <strong>of</strong> the GF-complex.), F. proliferatum (MP-D), F. subglutinans (MP-<br />

E), respectively. Identity <strong>of</strong> 3 strains was still under consideration. poster<br />

Aranda, Anabelle*, Viveros, Marian N. and Elley, Joanne T. Biological Sciences,<br />

The University <strong>of</strong> Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968-0519, USA.<br />

jellzey@utep.edu. Localization <strong>of</strong> G-Protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and<br />

Schizosaccharomyces pombe.<br />

It has been suggested that components <strong>of</strong> the cytoskeleton contribute to the<br />

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

signal transduction process in association with one or more members <strong>of</strong> the G protein<br />

family. Relatively high-affinity binding between dimeric tubulin and the<br />

alpha subunits <strong>of</strong> Gs and Gi1 has also been reported (Wang N. and Rasenick,<br />

1991). Tubulin has binding domains for microtubule-associated proteins. Tubulin<br />

modifies G-protein signaling. Heterotrimeric G-proteins regulate microtubule assembly<br />

in mammalian cells. G alpha inhibits microtubule assembly and increases<br />

microtubule disassembly by activating the intrinsic GTPase <strong>of</strong> tubulin. G beta<br />

gamma promotes microtubule assembly (Roychowdhury et al, 1999). In the present<br />

study, we have analyzed the interaction between alpha and beta gamma subunits<br />

<strong>of</strong> G proteins and tubulin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the Schizosaccharomyces<br />

pombe by immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence (Hagan and Hyams, 1988). Results<br />

from the immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence experiments were confirmed by electrophoresis<br />

and immunoblotting. We have obtained protein analyses and immunoblotting for<br />

S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. The visualization <strong>of</strong> the gamma and alpha tubulin is<br />

most evident in S. cerevisiae. There is evidence <strong>of</strong> a G-protein role in microtubule<br />

assembly/disassembly. poster<br />

Arenz, Brett E.*, Held, Ben W., Jurgens, Joel A. and Blanchette, Robert A. Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Plant Pathology, University <strong>of</strong> Minnesota, 495 Borlaug Hall, 1991<br />

Upper Buford Circle, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA. aren0058@umn.edu. Fungal<br />

diversity in wood and soils at the historic expedition huts <strong>of</strong> Ross Island,<br />

Antarctica, as revealed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE).<br />

Culture-dependent methods have long been the primary tool to determine<br />

the biodiversity <strong>of</strong> microorganisms in soils and other substrates. New molecular<br />

methods to study fungal pr<strong>of</strong>iles in samples from the environment have shown<br />

that these previous methods usually give an incomplete picture <strong>of</strong> all the organisms<br />

present. This study utilized denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE)<br />

to analyze the fungal diversity in wood and other materials brought to Ross Island,<br />

Antarctica by explorers Robert Scott and Ernest Shackleton. Fungal diversity in<br />

soils near the historic structures was also analyzed. Fungal specific primers were<br />

used to target the ITS 2 region which shows significant variability between<br />

species. The DNA was separated by DGGE, and bands extracted and sequenced.<br />

Although previously reported Antarctic fungi such as Geomyces, Cladosporium,<br />

Cadophora, and Phoma, were frequently identified, DNA <strong>of</strong> many species show<br />

very little similarity to sequences available in databases based on BLASTn<br />

searching. Species <strong>of</strong> Cadophora and Cladosporium were found associated with<br />

deteriorating historic woods and other artifacts. These fungi were also found in<br />

Antarctic soil samples. This work is providing a more comprehensive understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> the microbes found in Antarctica and provides new insights on the<br />

fungi attacking wood in the historic huts. contributed presentation<br />

Arnold, A. Elizabeth 1 *, Miadlikowska, Jolanta 2 , Higgins, K. Lindsay 2 , Dalling,<br />

James W. 3 , Gallery, Rachel E. 3 , Henk, Daniel A. 2 , Eells, Rebecca L. 2 , Vilgalys,<br />

Rytas J. 2 and Lutzoni, François 2 . 1 Division <strong>of</strong> Plant Pathology and Microbiology,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Plant Sciences, University <strong>of</strong> Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA,<br />

2 Department <strong>of</strong> Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA, 3 Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Plant Biology, University <strong>of</strong> Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA.<br />

arnold@ag.arizona.edu. What can environmental PCR tell us about foliar<br />

fungal endophyte communities?<br />

While it is clear that a tremendous diversity <strong>of</strong> endophytic fungi can be isolated<br />

from leaves using standard culturing techniques, the potential occurrence <strong>of</strong><br />

unculturable endophytes limits our understanding <strong>of</strong> the ecology, evolution, and<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> endophytic symbioses. In particular, environmental sampling may be<br />

key to uncovering endophytes with obligate host associations and/or vertical<br />

transmission, slowly growing species that do not occur readily in standard media,<br />

and species that lose in competitive interactions within cultured leaf pieces. Results<br />

<strong>of</strong> paired environmental sampling (direct PCR) + culturing approaches to assessing<br />

endophyte diversity and community structure in boreal, temperate, and<br />

tropical foliage, and tropical seeds, will be compared. In each case, environmental<br />

sampling was complementary to culturing: direct PCR recovered numerous<br />

lineages that were not represented in cultures from the same hosts, recovered sequences<br />

that have few close matches in GenBank, provided evidence for infections<br />

in apparently uninfected tissues, and fundamentally changed our view <strong>of</strong> the<br />

taxonomic distribution <strong>of</strong> endophytes present in each host species. In discussing<br />

these case studies, special attention will be given to (1) the importance <strong>of</strong> multilocus<br />

datasets for phylogenetic analyses <strong>of</strong> environmental samples; (2) methods<br />

<strong>of</strong> phylogenetic analysis that can result in reliable topologies given limited data<br />

from clones; (3) the utility <strong>of</strong> BLAST results based on ITS data for identifying<br />

clones; and (4) the utility <strong>of</strong> ITS genotype groups as functional taxonomic units<br />

for ecological analyses <strong>of</strong> environmental samples. symposium presentation<br />

Avis, Peter G.*, Leacock, Pat R. and Mueller, Greg M. Department <strong>of</strong> Botany,<br />

The Field Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL<br />

60605, USA. pavis@fieldmuseum.org. Potential changes in ectomycorrhizal<br />

fungal communities caused by nitrogen deposition in oak forests <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Chicago region.<br />

Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi may mediate the impact nitrogen (N) deposition<br />

has on temperate deciduous forests. To test this hypothesis, we are documenting<br />

the above- and belowground components <strong>of</strong> ECM communities in con-<br />

Continued on following page<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005 7

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

trol and experimentally N-fertilized treatments at three forest sites found along a<br />

N deposition gradient in the Chicago region. Field surveys <strong>of</strong> sporocarps in treatment<br />

plots have identified over 90 ECM fungal species across the three sites since<br />

2003. Over 200 <strong>of</strong> these collections were used to develop a reference database <strong>of</strong><br />

terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms (T-RFLP) for the identification<br />

<strong>of</strong> ECM collected belowground. In 2004, we conducted morphological and<br />

T-RFLP analyses <strong>of</strong> ECM collected from soil cores from each treatment plot.<br />

Early results indicate that the ECM communities in these sites are rich and potentially<br />

vulnerable to N increase. Over 130 likely species <strong>of</strong> ECM fungi have<br />

been identified from over 5000 oak root tips examined. Species richness estimates<br />

indicate that significantly fewer numbers <strong>of</strong> ECM species are found on oak roots<br />

in N fertilization treatments at two <strong>of</strong> three sites. We will continue to monitor<br />

ECM community responses to N fertilization over the next two years and also examine<br />

how the composition <strong>of</strong> these communities relates to their function within<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> N deposition. contributed presentation<br />

Badalyan, Suzanna M.*, Garibyan, Narine G. and Sakeyan, Carmen Z. Dept. <strong>of</strong><br />

Botany, Yerevan State University, Aleg Manoogian St., 375025, Yerevan, Armenia.<br />

badalyan_s@yahoo.com. Culture collection <strong>of</strong> Basidiomycetes fungi at<br />

the Yerevan State University (Armenia).<br />

Establishment and maintenance <strong>of</strong> Culture Collection <strong>of</strong> macroscopic fungi<br />

(Basidiomycetes) at the Yerevan State University are the way <strong>of</strong> preserving biodiversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> mushrooms and extending fungal genetic and biotechnological research<br />

in Armenia. Study <strong>of</strong> mushroom cultures can also be valuable in obtaining<br />

novel bio-pharmaceuticals and functional food additives with health-enhancing<br />

effect. Presently, the Collection comprises around 210 living strains <strong>of</strong> 60 mushroom<br />

species. They were mostly isolated in Armenia and obtained from other institutions.<br />

Among them, 35 species and 197 strains possess known medicinal<br />

properties. The Flammulina velutipes, Pleurotus ostreatus and Coprinus spp. collections<br />

are represented by a wide eco-geographical diversity <strong>of</strong> strains. ITSrDNA<br />

nucleotide sequence analyses <strong>of</strong> collected 25 species and 105 strains were<br />

carried out together with international collaborators. The project <strong>of</strong> genetic identification<br />

<strong>of</strong> Armenian medicinal mushrooms is currently realizing. Further extension<br />

<strong>of</strong> taxonomic, ecological and geographical diversity <strong>of</strong> species/strains and<br />

their genetic identification, as well as digitalization and creation <strong>of</strong> information<br />

DataBase are in progress. The catalogue <strong>of</strong> Culture Collection will be available<br />

soon. This research is supported by NATO (#FEL.RIG.980764) and DAAD<br />

(#548.104401.174) grants. poster<br />

Badalyan, Suzanna M. 1 * and Kües, Ursula 2 . 1 Dept. <strong>of</strong> Botany, Yerevan State University,<br />

Aleg Manoogian St., 375025, Yerevan, Armenia, 2 Section Molecular<br />

Wood Biotechnology, Institute <strong>of</strong> Forest Botany, Georg-August University, Büsgenweg<br />

2, D-37077 Göttingen, Germany. badalyan_s@yahoo.com. Mycelial<br />

morphology and growth characteristics <strong>of</strong> wood-related coprinoid mushrooms.<br />

Around 80 species <strong>of</strong> the traditional genus Coprinus (Coprinoid mushrooms)<br />

have been observed on wooden material. Mycelial micro-, macromorphology<br />

and growth characteristics <strong>of</strong> xylotrophic species Coprinus comatus, Coprinellus<br />

angulatus, C. bisporus, C. curtus, C. disseminatus, C. domesticus, C.<br />

ellisii, C. micaceus, C. xanthothrix, Coprinopsis atramentaria, C. cinerea, C.<br />

cothurnata, C. gonophylla, C. radians, C. romagnesiana, C. scobicola, C. strossmayeri<br />

and Parasola plicatilis have been studied. Cultures were grown on Malt-<br />

Extract Agar (MEA), Potato-Dextrose Agar (PDA) and Glucose-Peptone Agar<br />

(GPA) at 25 ∞C and pH 6. Growth rates and growth coefficients were highest on<br />

MEA (up to 85 mm and above 20, respectively), then PDA and GPA. Macromorphological<br />

characteristics were described after 10 days <strong>of</strong> growth. Oval and<br />

round shape clamps occur in most <strong>of</strong> the Coprini. Clamps were not found in some<br />

Coprinellus species. Material for micromorphological investigations was obtained<br />

by slide cultures. Hyphal loops were particularly formed in Coprinellus<br />

species. Arthroconidia were <strong>of</strong>ten observed, whereas blastic sporulation was rare.<br />

Chlamydospore formation is also typical for Coprini. Mycelial cysts, micr<strong>of</strong>ilaments<br />

and crystals were detected in some species.Thanks DAAD, NATO and<br />

Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt for financial support. poster<br />

Bahl, Justin, Jeewon, Rajesh* and Hyde, Kevin. Dept. Ecology & Biodiversity,<br />

The University <strong>of</strong> Hong Kong, Hong Kong, SAR, China. jbahl@hkusua.hku.hk.<br />

Intergeneric relationships <strong>of</strong> Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon: does phylogenetic<br />

analysis support the generic delineation?<br />

Species from the genera Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon are common<br />

saprobic fungi found in subtropical to tropical regions and mainly occurs on<br />

monocotyledonous hosts. Both genera are <strong>of</strong>ten found on the same host. Based on<br />

morphology these genera share many similarities and have resulted in difficulties<br />

in assigning taxa. The most significant delineating characters are ascomata position<br />

and morphology. Based on parsimony and likelihood analyses <strong>of</strong> multi-locus<br />

partial sequences derived from nuclear encoded ribosomal DNA, beta-tubulin and<br />

RNA polymerase regions from fresh and dried herbarium material, an attempt has<br />

been made to assess which morphological characters are phylogenetically significant<br />

for generic delineation or whether the genera should be circumscribed under<br />

the priority name, Linocarpon. Analysis confirmed that the two genera are not<br />

monophyletic and indicates parallel evolution <strong>of</strong> morphological and ecological<br />

8 <strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005<br />

characters. Results are discussed in relation to the significance <strong>of</strong> morphological<br />

characters currently used in the taxonomy <strong>of</strong> Linocarpon and Neolinocarpon.<br />

contributed presentation<br />

Barnes, Irene*, Wingfield, Michael J. and Wingfield, Brenda D. Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Genetics, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University <strong>of</strong><br />

Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa. irene.barnes@fabi.up.ac.za. Development<br />

<strong>of</strong> microsatellite markers for the red band needle blight pathogen Dothistroma<br />

septosporum using two different isolation methods.<br />

Very little is known regarding the population biology <strong>of</strong> Dothistroma septosporum,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most important pathogens <strong>of</strong> plantation grown pines in the<br />

southern hemisphere. Thus, twelve sets <strong>of</strong> microsatellite markers have been developed<br />

to study the population dynamics <strong>of</strong> this pathogen. Two techniques,<br />

ISSR-PCR and FIASCO enrichment were used to screen for microsatellite rich<br />

regions. ISSR-PCR was effective in locating many microsatellite sites. However,<br />

after the necessary genome walking, many <strong>of</strong> the microsatellites were found to be<br />

redundant artifacts <strong>of</strong> the initial primers used. With FIASCO, variable success<br />

was observed depending primarily on the primer combination used in the enrichment.<br />

In one screen, 57 % <strong>of</strong> the clones contained microsatellites, in others, none<br />

were found. From a total <strong>of</strong> 22 primer pairs, 11 were found to be polymorphic<br />

amongst isolates <strong>of</strong> D. septosporum. An additional primer was polymorphic between<br />

D. pini and D. septosporum and can be used for further diagnostic purposes<br />

within populations. Cross-species amplification was successful in D. pini, D.<br />

rhabdoclinis and Mycosphaerella dearnessi. Future studies using these primers<br />

will focus on gaining an improved understanding <strong>of</strong> the population structure, genetic<br />

diversity, gene flow and the genetic relatedness between different populations<br />

<strong>of</strong> these important tree pathogens. poster<br />

Barnes, Irene 1 *, Crous, Pedro W. 2 , Wingfield, Michael J. 1 and Wingfield, Brenda<br />

D. 11 Department <strong>of</strong> Genetics, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute<br />

(FABI), University <strong>of</strong> Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 0002, 2 Centraalbureau<br />

voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Fungal Biodiversity Centre, P.O. Box 85167,<br />

3508 AD Utrecht, The Netherlands. irene.barnes@fabi.up.ac.za. Multigene phylogenetic<br />

analyses reveal that Dothistroma septosporum and D. pini represent<br />

two distinct taxa and a serious threat to pine forestry.<br />

The sudden increase in severity <strong>of</strong> the red band needle blight disease in the<br />

U.K., Canada and parts <strong>of</strong> Europe where Dothistroma has been present for decades<br />

is a matter <strong>of</strong> great concern. Although the etiology <strong>of</strong> the disease is well known,<br />

phylogenetic and population level relationships amongst isolates <strong>of</strong> the fungus are<br />

poorly understood. We have thus constructed multigene phylogenies for isolates <strong>of</strong><br />

Dothistroma from 13 different countries. These have illustrated that the isolates are<br />

separated into two distinct lineages representing two discrete species and supported<br />

by morphological differences. The one species, referred to as D. septosporum<br />

occurs worldwide and infects over 30 species <strong>of</strong> pines. It is the major cause <strong>of</strong> the<br />

serious blight disease plaguing Pinus radiata plantations in New Zealand, Chile<br />

and other Southern Hemisphere countries The second species, D. pini, is restricted<br />

in its distribution to the North Central United States where it causes a serious disease<br />

on exotic P. nigra. A simple ITS-PCR-RFLP is also presented that allows accurate<br />

and rapid distinction between the two species. contributed presentation<br />

Baroni, Timothy J. 1 *, Lindner Czederpiltz, Daniel L. 2 , Lodge, D. Jean 3 , H<strong>of</strong>stetter,<br />

Valérie 4 and Franco-Molano, Ana Esperanza 5 . 1 Department <strong>of</strong> Biological<br />

Sciences, State University <strong>of</strong> New York, College at Cortland, Cortland, NY<br />

13045, USA, Center for Forest Mycology Research, USDA Forest Service, Forest<br />

Products Laboratory, One Gifford Pinchot Dr., Madison, WI 53726-2398,<br />

USA, Center for Forest Mycology Research, USDA Forest Service, P.O. Box<br />

1377, Luquillo, PR 00773-1377, USA, 4 Botany Department, Duke University,<br />

Durham, NC 27708-0338, USA, 5 Laboratorio de Taxonomía de Hongos, Instituto<br />

de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, A.A.1226, Medellín, Colombia. baronitj@cortland.edu.<br />

Arthrosporella, a recently rediscovered neotropical<br />

genus, is phylogenetically related to Termitomyces in the Lyophylleae.<br />

In 1996, Sharon Cantrell and TJB collected an odd nail-shaped agaric covered<br />

with dark brown conidia in Puerto Rico; that collection could not be named<br />

at that time. Over the next 9 years <strong>of</strong> intense collecting, this odd arthrospore-producing<br />

species was collected only three more times in Puerto Rico, but also twice<br />

in the Dominican Republic. TJB realized this was a new species <strong>of</strong> Arthrosporella,<br />

originally described by Rolf Singer as a monotypic genus from Argentina. A<br />

second, distinctly different and new conidia producing agaricoid species was<br />

found just recently in Colombia by AEFM, and we now know <strong>of</strong> two other collections<br />

<strong>of</strong> this taxon from the Dominican Republic by Egon Horak and TJB.<br />

Very recently (August 2004) a third new, and completely different arthrosporeproducing<br />

agaricoid species was found by TJB, DJL and CDL, fruiting abundantly<br />

in the cloud forest on the highest peak in Belize (Doyle’s Delight). All <strong>of</strong><br />

these new taxa possess siderophilous granules in the basidia. Phylogenetic analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> nLSU indicates, with significant support, the monophyly <strong>of</strong> Arthrosporella<br />

with Termitomyces (Lyophylleae) and suggests a sister relationship between these<br />

two genera. All collections <strong>of</strong> Arthrosporella appear to be saprotrophic and not<br />

termitophilous, thus perhaps indicating a closer relationship with Podabrella,<br />

which is also in this branch <strong>of</strong> the Lyphylleae clade. poster<br />

Continued on following page

Barrett, Luke G., Thrall, Peter H., Burdon, Jeremy J. and van der Merwe, Marlien<br />

M.* Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, CSIRO – Plant Industry, GPO Box<br />

1600, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia. marlien.vandermerwe@csiro.au Pancontinental<br />

patterns <strong>of</strong> genetic variation in the rust fungus Melampsora lini.<br />

The Linum marginale-Melampsora lini plant-pathogen interaction is endemic<br />

to Australia and has been a focus <strong>of</strong> epidemiological and coevolutionary<br />

studies for more than a decade. Considerable variation for both host resistance and<br />

pathogen virulence has been shown at a range <strong>of</strong> spatial scales from the local to<br />

the continental. Here we report on a study using AFLP and SSR markers to examine<br />

pancontinental patterns <strong>of</strong> genetic variation in 102 clonal lines <strong>of</strong> M. lini<br />

representing 35 populations. Molecular marker genotypes partition all <strong>of</strong> the isolates<br />

into two major lineages, and in combination with subsequent sequencing <strong>of</strong><br />

beta-tubulin and elongation factor genes suggest a possible hybrid origin for one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the lineages. Subsequent comparison with data on phenotypic variation for virulence<br />

in a subset <strong>of</strong> these isolates also demonstrates striking differences between<br />

the two lineages in terms <strong>of</strong> pathogenicity on the host L. marginale. Molecular genetic<br />

variation within the lineages was very limited, and within populations both<br />

AFLP and SSR markers regularly failed to distinguish among several lines with<br />

different pathotypes. These results are important for developing an understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> how pathogen virulence might evolve within natural populations. poster<br />

Barrow, Jerry R.*, Lucero, Mary L., Osuna-Avila, Pedro, Reyes-Vera, Isaac and<br />

Aaltonen, Ronald E. USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, Las Cruces, NM<br />

88003, USA. jbarrow@nmsu.edu. Hybrid vigor, structural modification and<br />

enhanced plant performance induced by symbiotic fungi-plant interactions.<br />

Hybrid vigor, structural modification and enhanced plant performance induced<br />

by symbiotic fungi-plant interactions. Communities <strong>of</strong> symbiotic fungi are<br />

intrinsically integrated with single cells, tissues and organs <strong>of</strong> desert plants. They<br />

are obligately associated with living tissues and generally cannot be isolated and<br />

cultured separately. Symbiotic fungi indigenous to native desert plants were transferred,<br />

using cell culture methods, to non-host plants and reciprocally transferred<br />

between native grasses. Crop and native plants, with recipient fungi have astounding<br />

and increased levels <strong>of</strong> vigor. Up to five-fold increases in root and shoot<br />

biomass and substantial morphological changes and reproductive potential were<br />

obtained. Enhanced chlorophyll and phosphorous content were common responses.<br />

Once integrated, fungi were intimately interfaced with the plasmalema<br />

<strong>of</strong> the new host plant and were ecto-cytoplasmically inherited. This technology<br />

accesses a previously unexplored source <strong>of</strong> genetic variability within native<br />

ecosystems with the potential <strong>of</strong> immediate transfer to improve tolerance <strong>of</strong> native<br />

and crop plants to stress, disease and pests. Symbiotic fungal transfers provides<br />

a powerful alternative for genetic improvement <strong>of</strong> plants. contributed presentation<br />

Bartnicki-García, Salomón. Microbiology Dept., CICESE, Ensenada, Baja California,<br />

22860, México. bartnick@cicese.mx. Introductory remarks: Current<br />

perspectives in hyphal morphogenesis.<br />

Hyphal morphogenesis is clearly the most basic developmental process in<br />

mycology. The origin <strong>of</strong> the fungal kingdom could be traced to the “invention” <strong>of</strong><br />

hyphal morphogenesis, i.e. the ability <strong>of</strong> a cell to form long tubular walls by tip<br />

growth. Not surprisingly, over the years, fungal biologists have become increasingly<br />

interested in elucidating the cellular and molecular basis <strong>of</strong> hyphal morphogenesis.<br />

The problem revolves basically about understanding the mechanism(s)<br />

responsible for polarized growth <strong>of</strong> the cell wall. A number <strong>of</strong> structural and molecular<br />

players have been identified but the mechanism cannot be attributed to a<br />

single gene or protein. Polarized secretion probably requires a specific concerted<br />

action between cytoskeleton and secretory vesicles to produce a pattern <strong>of</strong> vesicle<br />

discharge that would generate cells with a pr<strong>of</strong>ile described by the hyphoid equation:<br />

y = x cot (xV/N). This symposium on Advances in Fungal Morphogenesis<br />

will cover developments in different fronts: a new way <strong>of</strong> probing the surface<br />

properties <strong>of</strong> the hyphal wall (S. Kaminskyj), assessing the importance <strong>of</strong> protein<br />

glycosylation in the maintenance <strong>of</strong> hyphal growth (B. Shaw), and analyzing the<br />

role <strong>of</strong> the Spitzenkörper in apical growth (M. Riquelme). symposium presentation<br />

Baucom, Deana L.*, Bruhn, Johann N. and Mihail, Jeanne D. Division <strong>of</strong> Plant<br />

Sciences, University <strong>of</strong> Missouri, Columbia MO 65211, USA. dlba3c@mizzou.edu.<br />

Armillaria species involved in Missouri Ozark forest decline.<br />

In the Missouri Ozark Mountains, Armillaria spp. contribute to oak decline.<br />

To investigate the distributions and roles <strong>of</strong> Armillaria spp., 142 isolates collected<br />

in 2002 from 40 plots were identified. Amplification <strong>of</strong> IGS1 followed by restriction<br />

with AluI identified 121 isolates as A. mellea (52 %), A. gallica (38 %),<br />

and A. tabescens (10 %). Two new RFLP patterns were found to represent 41 %<br />

<strong>of</strong> A. mellea and 17 % <strong>of</strong> A. gallica isolates. Isolates yielding these patterns are<br />

currently being characterized by sequence analysis <strong>of</strong> IGS1. Major hosts were<br />

dogwood (44 %), red oaks (18 %), and white oaks (7 %). Armillaria mellea predominated<br />

on both white and red oaks; A. mellea and A. gallica occurred equally<br />

on dogwood. Recently killed trees provided 28 % <strong>of</strong> study isolates. Armillaria<br />

was almost universally present on recently killed trees. Red oaks, dogwood, and<br />

white oaks provided 38 %, 32 %, and 10 % <strong>of</strong> recent mortality isolates, respectively.<br />

Nearly all recent oak mortality yielded A. mellea. Recent dogwood mor-<br />

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

tality yielded A. gallica (54 %) more frequently than A. mellea (38 %). Ozark oak<br />

decline affects red oaks and dogwoods most heavily. The Armillaria sp. which<br />

most commonly contributed to oak mortality on our plots in 2002 was A. mellea,<br />

though A. gallica was more commonly recovered from recent dogwood mortality.<br />

We found little evidence <strong>of</strong> mortality caused by A. tabescens. poster<br />

Beeson, Esther 1 , Beltz, Shannon 2 , Klich, Maren 2 and Bennett, Joan W. 1 * 1 Tulane<br />

University, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2 Southern Regional Resource Center, New<br />

Orleans, LA, USA. ebeeson1@cox.net. Sclerotial production in Aspergillus<br />

flavus varies with temperature and nitrogen source.<br />

Twenty strains <strong>of</strong> Aspergillus flavus from the culture collection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Southern Regional Research Laboratory, New Orleans, LA, were grown on defined<br />

and complex media at 25 o C and 37 o C for one week. Colonies were<br />

screened for sclerotial production as well as other colony characters including production<br />

<strong>of</strong> conidia, floccose hyphae, and mycelial pigment. When grown on complex<br />

media with yeast extract as the nitrogen source, 9 <strong>of</strong> the strains produced<br />

sclerotia at 25 o C and 11 produced sclerotia at 37 o C. When grown on a defined<br />

medium with nitrate as nitrogen source, 8 <strong>of</strong> the strains produced sclerotia at 37<br />

o C and 5 produced sclerotia at 25 o C. When ammonium was used as the nitrogen<br />

source, only one strain produced sclerotia at 37 o C and there was no sclerotial production<br />

at 25 o C. Sporulation was sparse or absent for all strains grown on ammonium<br />

at 37 o C. When microarrays <strong>of</strong> the A. flavus genome become available,<br />

these data will be useful in designing conditions for RNA isolation in order to<br />

probe the genes involved in sclerotial formation. poster<br />

Bennett, Chandalin 1 *, Newcombe, George 1 and Aime, M. Catherine 2 . 1 Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> Forest Resources, University <strong>of</strong> Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844, USA,<br />

2 USDA ARS Systematic Botany and Mycology Lab, Beltsville, Maryland 20705,<br />

USA. benn4449@uidaho.edu. Regional studies <strong>of</strong> Melampsora on Salix in the<br />

Pacific Northwest.<br />

Melampsora epitea Thuem. is a species complex that represents all willow<br />

rusts in N. <strong>America</strong>. To better understand how much host-specialization and genetic<br />

diversity exists in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), a large-scale host-range inoculation<br />

study was performed along with ITS sequencing, morphological analysis,<br />

and a two-year field survey. Distinct host-specificity was shown for three<br />

different Melampsora isolates inoculated on nearly equal sets <strong>of</strong> 440 willows.<br />

Less than 20 percent <strong>of</strong> the plants in each experiment were susceptible to the inoculum<br />

and greater than 15 percent <strong>of</strong> those showed some signs <strong>of</strong> resistance. The<br />

genetic sequencing resulted in four distinct clades, the largest <strong>of</strong> which likely represents<br />

a complex in this region. The other three clades were strongly divergent<br />

from the complex. There was up to three genetically distinct rusts present in a<br />

given geographic location and four or more genetically distinct rusts on a given<br />

Salix sp. There was found at most two distinct rusts on the same species from the<br />

same population. It’s evident that willow rusts are incredibly diverse in the PNW.<br />

Every experimental inoculum was specialized in its host range and the genetic diversity<br />

was spread across four unique and highly divergent clades. symposium<br />

presentation<br />

Bennett, Joan W. Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118, USA.<br />

jbennett@tulane.edu. Industrial mycology: from Takamine’s diastase to<br />

TIGR’s database.<br />

Industrial mycology has its roots in numerous food fermentations that were<br />

developed early in human history. Of these, the Japanese koji process, utilizing<br />

Aspergillus oryzae , is <strong>of</strong> particular interest because the first microbial enzyme<br />

ever patented was a secreted diastase (amylase) isolated from A. oryzae by Dr. Jokichi<br />

Takamine, a Japanese chemist working in the U.S.A during the late nineteenth<br />

century. In the first half <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century, several filamentous fungi<br />

were harnessed for the production <strong>of</strong> additional commercial enzymes and for organic<br />

acids. Although the discovery <strong>of</strong> penicillin and the subsequent golden age<br />

<strong>of</strong> antibiotics transformed fermentation technology, the molecular biology <strong>of</strong> industrial<br />

molds lagged behind that <strong>of</strong> model species. Now, in the twenty-first century,<br />

genomic research has ushered in a new era <strong>of</strong> understanding. Genome projects<br />

for several Aspergillus species are completed or underway, revealing new<br />

insights into secondary metabolism, carbon and nitrogen regulation, and other genetic<br />

control mechanisms. aymposium presentation<br />

Berbee, Mary L. 1 *, James, Tim Y. 2 , Longcore, Joyce E. 3 , Stajich, Jason 4 and Vilgalys,<br />

Rytas J. 2 . 1 Dept. <strong>of</strong> Botany, University <strong>of</strong> British Columbia, V6T 1Z4<br />

Canada, 2 Dept. <strong>of</strong> Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 USA, 3 Biological<br />

Sciences, University <strong>of</strong> Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5722 USA, 4 Dept. <strong>of</strong> Molecular<br />

Genetics and Microbiology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA.<br />

berbee@interchange.ubc.ca. What makes a fungus? Fungal-specific genes<br />

from EST libraries <strong>of</strong> the basal fungi Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and<br />

Mortierella verticillata.<br />

The Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota include ancient fungal lineages that<br />

may have originated hundreds <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong> years before plants invaded land. We<br />

looked for shared genes that distinguish the fungi from other kingdoms through<br />

comparison <strong>of</strong> expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries, from a chytrid, Batrachochytrium<br />

dendrobatidis (1588 ESTs, average length, 572 nucleotides) and<br />

Continued on following page<br />

<strong>Inoculum</strong> <strong>56</strong>(4), August 2005 9

MSA ABSTRACTS<br />

from Mortierella verticillata, a readily cultured terrestrial mold in the Zygomycota<br />

(1278 ESTs, average length, 5<strong>56</strong> nucleotides). Of 1247 non-redundant ESTs<br />

from B. dendrobatidis, 100 were ‘fungal- specific’ in that sequence similarity<br />

within fungi is high but drops <strong>of</strong>f sharply beyond the kingdom level. From M. verticillata,<br />

64 ESTs were fungal-specific. Fungal-specific genes included six subfamilies<br />

<strong>of</strong> chitin synthases that arose through ancient gene duplications. Suggesting<br />

that early fungi had to scavenge for iron, B. dendrobatidis and higher<br />

fungi share a high affinity iron permease. Septins are also present in animals, but<br />

they help control the form <strong>of</strong> fungi during development. We found four septin paralogues<br />

among ESTs from Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and two from<br />

Mortierella verticillata. The septins from the spheroidal chytrid appeared to be<br />

basal to genes from other fungi. contributed presentation<br />

Bérube, Jean A. 1 *, Stefani, Frank O.P. 1 and Sokolski, S. 1 Canadian Forest Service,<br />

1055 du PEPS, P.O. Box 3800, Ste-Foy, QC, G1V 4C7 Canada.<br />

jberube@cfl.forestry.ca. Comparison <strong>of</strong> foliar endophyte biodiversity from<br />

three boreal conifers.<br />

We compared the foliar endophyte biodiversity <strong>of</strong> white spruce (Picea glauca),<br />

black spruce (P. mariana) and eastern white pine (Pinus strobus). Asymptomatic<br />

healthy needles were collected from 67 conifer populations in eastern Canada,<br />

surface sterilized and then plated on nutrient agar. The ribosomal ITS region<br />

were amplified, sequenced and analyzed using maximum parsimony and<br />

Bayesian inference. Results from morphological and molecular studies indicate<br />

white spruce is hosting as many as 49 fungal endophyte species, black spruce is<br />

hosting 42 species and white pine is hosting 30 species. Only four endophyte<br />