Classical and augmentative biological control against ... - IOBC-WPRS

Classical and augmentative biological control against ... - IOBC-WPRS

Classical and augmentative biological control against ... - IOBC-WPRS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>IOBC</strong><br />

OILB<br />

<strong>WPRS</strong><br />

SROP<br />

In te rn atio na l O rg an isatio n fo r B iolog ical an d In teg ra te d C on tro l o f N o xiou s<br />

A nim als a n d P lan ts: W e st Pa la ea rctic R e gio na l S e ctio n<br />

O rg an isatio n In te rn a tio n ale d e L utte B io lo giqu e e t In te g ré e con tre les A n im a ux et le s<br />

P la ntes N u isibles: S e ction R é gio na le O u est P a lé a rctiq ue<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong><br />

<strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> diseases <strong>and</strong> pests:<br />

critical status analysis <strong>and</strong> review of factors<br />

influencing their success<br />

Edited by Philippe C. Nicot<br />

2011

The content of the contributions is the responsibility of the authors<br />

Published by the International Organization for Biological <strong>and</strong> Integrated Control of Noxious<br />

Animals <strong>and</strong> Plants, West Palaearctic Regional Section (<strong>IOBC</strong>/<strong>WPRS</strong>)<br />

Publié par l'Organisation Internationale de Lutte Biologique et Intégrée contre les Animaux<br />

et les Plantes Nuisibles, Section Ouest Palaéarctique (OILB/SROP)<br />

Copyright <strong>IOBC</strong>/<strong>WPRS</strong> 2011<br />

ISBN 978-92-9067-243-2<br />

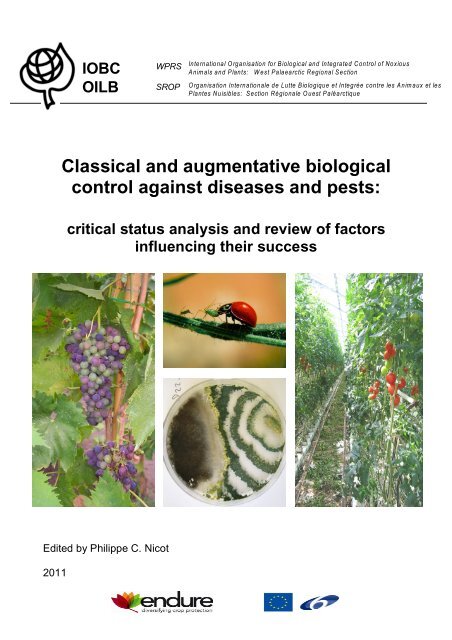

Cover page photo credits:<br />

1<strong>and</strong> 3: M Ruocco, CNR<br />

2: Anderson Mancini<br />

4. P.C. Nicot, INRA<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4

Preface<br />

One of the Research Activities (RA 4.3) of the European Network for Durable Exploitation of crop<br />

protection strategies (ENDURE * ) has brought together representatives of industry <strong>and</strong> scientists<br />

from several European countries with experience ranging from fundamental biology to applied field<br />

work on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> pests <strong>and</strong> diseases. The unique diversity of expertise <strong>and</strong><br />

concerns allowed the group to set up very complementary approaches to tackle the issue of the<br />

factors of success of bio<strong>control</strong>.<br />

The initial part of the work accomplished by this group consisted in a thorough review of<br />

scientific literature published on all types of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>. Although it had to be focused on<br />

selected key European crops <strong>and</strong> their major pests <strong>and</strong> pathogens, this review is unique in the scope<br />

of the topics it covered <strong>and</strong> in the comprehensive inventories it allowed to gather on the potential of<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>and</strong> factors of success at field level.<br />

In parallel with identifying knowledge gaps <strong>and</strong> key factors from published research,<br />

information was gathered on aspects linked to the production <strong>and</strong> commercialization of bio<strong>control</strong><br />

agents.<br />

These results, complemented by the views of experts in the field of bio<strong>control</strong> consulted at the<br />

occasion of meetings of <strong>IOBC</strong>-wprs, allowed the identification of majors gaps in knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

bottlenecks for the successful deployment of bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>and</strong> lead to the proposition of key issues for<br />

future work by the research community, the field of development <strong>and</strong> prospects for technological<br />

improvement by industry.<br />

Avignon, June 2011<br />

Philippe C. Nicot<br />

*<br />

EU FR6 project 031499, funded in part by the European Commission<br />

i

Contributors<br />

ALABOUVETTE Claude,<br />

INRA, UMR1229, Microbiologie du Sol et de l'Environnement, 17 rue Sully,<br />

F-21000 Dijon, France<br />

Claude.Alabouvette@dijon.inra.fr<br />

current address: AGRENE, 47 rue Constant Pierrot 21000 DIJON, c.ala@agrene.fr<br />

BARDIN Marc,<br />

INRA, UR 407, Unité de Pathologie végétale, Domaine St Maurice, BP 94,<br />

F-84140 Montfavet, France<br />

Marc.Bardin@avignon.inra.fr<br />

BLUM Bernard,<br />

International Bio<strong>control</strong> Manufacturers Association, Blauenstrasse 57,<br />

CH-4054 Basel, Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

bjblum.ibma@bluewin.ch<br />

DELVAL Philippe,<br />

ACTA, Direction Scientifique, Technique et Internationale,<br />

ICB / VetAgroSup, 1 avenue Claude Bourgelat , F-69680 Marcy l'Etoile, France<br />

Philippe.Delval@acta.asso.fr<br />

GIORGINI Massimo,<br />

CNR, Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante, via Università 133,<br />

80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

giorgini@ipp.cnr.it<br />

HEILIG Ulf,<br />

IBMA, 6 rue de Seine, F-78230 Le Pecq, France<br />

ulf.heilig@cegetel.net<br />

KÖHL Jürgen,<br />

Wageningen UR, Plant Research International, Droevendaalsesteeg 1,<br />

P.O. Box 69, 6700 AB Wageningen, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

jurgen.kohl@wur.nl<br />

LANZUISE Stefania,<br />

UNINA, Dip. Arboricoltura, Botanica e Patologia Vegetale,<br />

Università di Napoli Federico II, via Università 100, 80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

ii

LORITO Matteo<br />

UNINA, Dip. Arboricoltura, Botanica e Patologia Vegetale,<br />

Università di Napoli Federico II, via Università 100, 80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

lorito@unina.it<br />

MALAUSA Jean Claude,<br />

INRA, UE 1254, Unité expérimentale de Lutte Biologique,<br />

Centre de recherche PACA, 400 route des Chappes, BP 167,<br />

F-06903 Sophia Antipolis, France<br />

Jean-Claude.Malausa@sophia.inra.fr<br />

NICOT Philippe C.,<br />

INRA, UR 407, Unité de Pathologie végétale, Domaine St Maurice, BP 94,<br />

F-84140 Montfavet, France<br />

Philippe.Nicot@avignon.inra.fr<br />

RIS Nicolas,<br />

INRA, UE 1254, Unité expérimentale de Lutte Biologique,<br />

Centre de recherche PACA, 400 route des Chappes, BP 167,<br />

F-06903 Sophia Antipolis, France<br />

Nicolas.Ris@sophia.inra.fr<br />

RUOCCO Michelina,<br />

CNR, Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante, via Università 133,<br />

80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

ruocco@ipp.cnr.it<br />

VINALE Francesco,<br />

CNR, Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante, via Università 133,<br />

80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

frvinale@unina.it<br />

WOO Sheridan<br />

UNINA, Dip. Arboricoltura, Botanica e Patologia Vegetale,<br />

Università di Napoli Federico II, via Università 100, 80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

woo@unina.it<br />

iii

List of Tables<br />

Table 1:<br />

Table 2:<br />

Table 3:<br />

Table 4:<br />

Table 5:<br />

Table 6:<br />

Table 7:<br />

Table 8:<br />

Scientific papers published between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 2008 on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

<strong>against</strong> major plant diseases (from CAB Abstracts® database). ..........................................2<br />

Numbers of references on bio<strong>control</strong> examined per group of disease/plant<br />

pathogen......................................................................................................................3<br />

Numbers of different bio<strong>control</strong> compounds <strong>and</strong> microbial species reported as<br />

having successful effect <strong>against</strong> key airborne pathogens/diseases of selected<br />

crops. ..........................................................................................................................4<br />

Microbial species of fungi/oomycetes, yeasts <strong>and</strong> bacteria reported to have a<br />

significant effect <strong>against</strong> five main types of airborne diseases or pathogens in<br />

laboratory conditions or in the field.................................................................................5<br />

References extracted from the CAB Abstracts database <strong>and</strong> examined for<br />

reviewing augmentation <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in grapevine. .................................................13<br />

Bio<strong>control</strong> agents evaluated in researches on <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

of pests in grapevine. ..................................................................................................15<br />

Number of references on <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> agents per group <strong>and</strong><br />

species of target pest in grapevine.................................................................................16<br />

Number of references reporting data on the efficacy of <strong>augmentative</strong><br />

bio<strong>control</strong> of pests in grapevine. ...................................................................................18<br />

Table 9: Recent introductions of parasitoids as <strong>Classical</strong> Bio<strong>control</strong> agents ....................................31<br />

Table 10:<br />

Table 11:<br />

Consulted sources of information on authorized bio<strong>control</strong> plant protection<br />

products in five European countries: .............................................................................34<br />

Active substances suitable for <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> listed on Annex I of<br />

91/414/EEC (EU Pesticide Database) - Status on 21st April 2009.....................................36<br />

Table 12: Evidence for, <strong>and</strong> effectiveness of, induced resistance in plants by<br />

Trichoderma species (Harman et al., 2004a). .................................................................47<br />

Table 13:<br />

Table 14:<br />

Table 15:<br />

Table 16:<br />

Trichoderma-based preparations commercialized for <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of<br />

plant diseases. ............................................................................................................49<br />

Compared structure of the production costs for a microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agent<br />

(MBCA) <strong>and</strong> a chemical insecticide (source IBMA). ......................................................59<br />

Compared potential costs of registration for a microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agent<br />

(MBCA) <strong>and</strong> a chemical pesticide (source IBMA)..........................................................60<br />

Compared estimated market potential for a microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agent<br />

(MBCA) <strong>and</strong> for a chemical pesticide (source: IBMA) ....................................................60<br />

iv

List of Tables (continued)<br />

Table 17:<br />

Table 18:<br />

Table 19:<br />

Table 20:<br />

Table 21:<br />

Compared margin structure estimates for the production <strong>and</strong> sales of a<br />

microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agent (MBCA) <strong>and</strong> a chemical pesticide (source IBMA)....................61<br />

Production systems selected for a survey of factors influencing bio<strong>control</strong> use<br />

in Europe (source IBMA) ............................................................................................63<br />

Geographical distribution of sampling sites for a survey of factors influencing<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> use in Europe (source IBMA) .......................................................................63<br />

Structure of the questionnaire used in a survey of European farmers <strong>and</strong><br />

retailers of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> products...........................................................................64<br />

Impact of twelve factors on the future use of bio<strong>control</strong> agents by European<br />

farmers according to a survey of 320 farmers .................................................................66<br />

v

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1:<br />

Figure 2:<br />

Evolution of the yearly number of publications dedicated to <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

of plant diseases based on a survey of the CAB Abstracts® database. .................................1<br />

Range of efficacy of 157 microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agents <strong>against</strong> five main types<br />

of airborne diseases. Detailed data are presented in Table 4.............................................10<br />

Figure 3: Number of papers per year published during 1998-2008 concerning<br />

<strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of pests in grapevine......................................................13<br />

Figure 4:<br />

Figure 5:<br />

Figure 6:<br />

Figure 7:<br />

Figure 8:<br />

Figure 9:<br />

Figure 10:<br />

Figure 11:<br />

Figure 12:<br />

Groups of bio<strong>control</strong> agents investigated in <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

researches in grapevine. Number of references for each group is reported..........................19<br />

Groups of target pests investigated in <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

researches in grapevine. Number of references for each group is reported..........................19<br />

Large-scale temporal survey of the publications associated with classical<br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>........................................................................................................26<br />

Relative importance of the different types of bio<strong>control</strong> during the temporal<br />

frame [1999-2008]......................................................................................................27<br />

Number of pest species <strong>and</strong> related citation rate by orders during the period<br />

[1999 ; 2008] .............................................................................................................28<br />

Relationships between the number of publications associated to the main<br />

pests <strong>and</strong> the relative percentage of ClBC related studies.................................................29<br />

Frequencies of papers <strong>and</strong> associated median IF related to the different<br />

categories of work ......................................................................................................30<br />

Estimated sales of bio<strong>control</strong> products in Europe in 2008 (in Million €). The<br />

estimates were obtained by extrapolating use patterns in a representative<br />

sample of EU farmers..................................................................................................64<br />

Estimated distribution of bio<strong>control</strong> use among types of crops in 2008 in<br />

Europe ......................................................................................................................65<br />

vi

Contents<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Potential of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

1. Protection <strong>against</strong> plant pathogens of selected crops...................................................1<br />

P. C. Nicot, M. Bardin, C. Alabouvette, J. Köhl <strong>and</strong> M. Ruocco<br />

Chapter 2<br />

Potential of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

2. Beneficials for <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> insect pests. The<br />

grapevine case study .......................................................................................................12<br />

M. Giorgini<br />

Chapter 3<br />

Potential of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

3. Research <strong>and</strong> development in classical <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> with<br />

emphasis on the recent introduction of insect parasitoids .......................................20<br />

N. Ris <strong>and</strong> J.C. Malausa<br />

Chapter 4<br />

Registered Bio<strong>control</strong> Products <strong>and</strong> their use in Europe...................................................34<br />

U. Heilig, P. Delval <strong>and</strong> B. Blum<br />

Chapter 5<br />

Identified difficulties <strong>and</strong> conditions for field success of bio<strong>control</strong>.<br />

1. Regulatory aspects ................................................................................................. 42<br />

U. Heilig, C. Alabouvette <strong>and</strong> B.Blum<br />

Chapter 6<br />

Identified difficulties <strong>and</strong> conditions for field success of bio<strong>control</strong>.<br />

2. Technical aspects: factors of efficacy ...........................................................................45<br />

M. Ruocco, S. Woo, F. Vinale, S. Lanzuise <strong>and</strong> M. Lorito<br />

Chapter 7<br />

Identified difficulties <strong>and</strong> conditions for field success of bio<strong>control</strong>.<br />

3. Economic aspects: cost analysis ....................................................................................58<br />

B. Blum, P.C. Nicot, J. Köhl <strong>and</strong> M. Ruocco<br />

Chapter 8<br />

Identified difficulties <strong>and</strong> conditions for field success of bio<strong>control</strong>.<br />

4. Socio-economic aspects: market analysis <strong>and</strong> outlook ..............................................62<br />

B. Blum, P.C. Nicot, J. Köhl <strong>and</strong> M. Ruocco<br />

Conclusions <strong>and</strong> perspectives<br />

Perspectives for future research-<strong>and</strong>-development projects on <strong>biological</strong><br />

<strong>control</strong> of plant pests <strong>and</strong> diseases.................................................................................. 68<br />

P.C. Nicot, B. Blum, J. Köhl <strong>and</strong> M. Ruocco<br />

vii

Appendices....................................................................................................................... 71<br />

For Chapter 1<br />

Appendix 1.<br />

Appendix 2.<br />

Appendix 3.<br />

Appendix 4.<br />

Appendix 5.<br />

Inventory of bio<strong>control</strong> agents described in primary literature<br />

(1998-2008) for successful effect <strong>against</strong> Botrytis sp. in laboratory<br />

experiments <strong>and</strong> field trials with selected crops ...........................................72<br />

Inventory of bio<strong>control</strong> agents described in primary literature<br />

(1998-2008) for successful effect <strong>against</strong> powdery mildew in<br />

laboratory experiments <strong>and</strong> field trials with selected crops. .......................102<br />

Inventory of bio<strong>control</strong> agents described in primary literature<br />

(1973-2008) for successful effect <strong>against</strong> the rust pathogens in<br />

laboratory experiments <strong>and</strong> field trials with selected crops.........................111<br />

Inventory of bio<strong>control</strong> agents described in primary literature<br />

(1973-2008) for successful effect <strong>against</strong> the downy mildew / late<br />

blight pathogens in laboratory experiments <strong>and</strong> field trials with<br />

selected crops............................................................................................115<br />

Inventory of bio<strong>control</strong> agents described in primary literature<br />

(1973-2008) for successful effect <strong>against</strong> Monilinia in laboratory<br />

experiments <strong>and</strong> field trials with selected crops .........................................122<br />

Appendix 6. Primary literature (2007-2009) on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong><br />

Fusarium oxysporum.................................................................................128<br />

For Chapter 2<br />

Appendix 7.<br />

Appendix 8.<br />

Number of references retrieved by using the CAB Abstracts<br />

database in order to review scientific literatures on <strong>augmentative</strong><br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in selected crops for Chapter 2. .....................................139<br />

Collection of data on <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of pests in<br />

grapevine. Each table refers to a group of bio<strong>control</strong> agents.......................141<br />

For Chapter 3<br />

Appendix 9.<br />

References on classical <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> insect pests<br />

(cited in Chapter 3)....................................................................................152<br />

For Chapter 4<br />

Appendix 10. Substances included in the "EU Pesticides Database" as of April 21<br />

2009..........................................................................................................163<br />

Appendix 11.<br />

Invertebrate beneficials available as <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> agents<br />

<strong>against</strong> invertebrate pests in five European countries. ................................171<br />

viii

Chapter 1<br />

Potential of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

1. Protection <strong>against</strong> plant pathogens of selected crops<br />

Philippe C. Nicot 1 , Marc Bardin 1 , Claude Alabouvette 2 , Jürgen Köhl 3 <strong>and</strong> Michelina Ruocco 4<br />

1 INRA, UR407, Unité de Pathologie Végétale, Domaine St Maurice, 84140 Montfavet, France<br />

2 INRA, UMR1229, Microbiologie du Sol et de l'Environnement, 17 rue Sully, 21000 Dijon, France<br />

3 Wageningen UR, Plant Research International, Droevendaalsesteeg 1, P.O. Box 69, 6700 AB<br />

Wageningen, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

4 CNR-IPP, Istituto pel la Protezione delle Piante, Via Univrsità 133, Portici (NA) Italy<br />

Evolution of the scientific literature<br />

The scientific literature published between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 2008 comprises a wealth of studies on<br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> diseases <strong>and</strong> pests of agricultural crops. A survey of the CAB Abstracts®<br />

database shows a steady increase in the yearly number of these publications from 20 in 1973 to over<br />

700 per year since 2004 (Figure 1).<br />

900<br />

Number of publications per year<br />

800<br />

700<br />

600<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010<br />

Publication year<br />

Figure 1:<br />

Evolution of the yearly number of publications dedicated to <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of plant<br />

diseases based on a survey of the CAB Abstracts ® database.<br />

This survey was further refined by entering keywords describing some of the major plant<br />

pathogens/diseases of cultivated crops in Europe, alone or cross-referenced with keywords<br />

indicating bio<strong>control</strong>. Among studies published in the period between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 2008 on these<br />

plant pathogens <strong>and</strong> pests, the percentage dedicated to <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> was substantial, but<br />

unequally distributed (Table 1). It was notably higher for studies on soil-borne (9.5% ± 1.6% as<br />

average ± st<strong>and</strong>ard error) than for those on air-borne diseases (2.8% ± 0.7%).<br />

1

Nicot et al.<br />

Table 1: Scientific papers published between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 2008 on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> major<br />

plant diseases (from CAB Abstracts ® database).<br />

Disease or plant pathogen<br />

Total number<br />

of references<br />

References on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

%<br />

Soil-borne:<br />

Fusarium 34 818 1 925 5.5<br />

Rhizoctonia 10 744 1 278 11.9<br />

Verticillium 7 585 592 7.8<br />

Pythium 5 772 821 14.2<br />

Sclerotinia 5 545 456 8.2<br />

Air-borne:<br />

rusts 29 505 360 1.2<br />

powdery mildews 18 026 251 1.4<br />

Alternaria 12 766 415 3.3<br />

anthracnose 12 390 351 2.8<br />

Botrytis 9 295 705 7.5<br />

downy mildews 8 456 80 1.0<br />

Phytophthora infestans 5 303 61 1.1<br />

Monilia rot 1 861 81 4.3<br />

Venturia 3 870 104 2.7<br />

Inventory of potential bio<strong>control</strong> agents (microbials, botanicals, other natural<br />

compounds)<br />

The scientific literature described above was further examined to identify bio<strong>control</strong> compounds<br />

<strong>and</strong> microbial species reported to have a successful effect. Due to the great abundance of<br />

references, it was not possible to examine the complete body of literature. The study was thus<br />

focused on several key diseases selected for their general importance on cultivated crops, <strong>and</strong> in<br />

particular on those crops studied in the case studies of the European Network for Durable<br />

Exploitation of crop protection strategies (ENDURE * ).<br />

Methodology<br />

Three steps were followed. The first step consisted in collecting the appropriate literature references<br />

for the selected key diseases/plant pathogens to be targeted by the study. The references were<br />

extracted from the CAB Abstracts ® database <strong>and</strong> downloaded to separate files using version X1 of<br />

EndNote (one file for each target group). The files were then distributed among the contributors of<br />

this task for detailed analysis.<br />

In the second step, every reference was examined <strong>and</strong> we recorded for each:<br />

- the types of bio<strong>control</strong> agents (Microbial, Botanical or Other compounds) under study <strong>and</strong> their<br />

Latin name (for living organisms <strong>and</strong> plant extracts) or chemical name<br />

- the Latin name of the specifically targeted pathogens,<br />

- the crop species (unless tests were carried out exclusively in vitro),<br />

- the outcome of efficacy tests.<br />

Two types of efficacy tests were distinguished: Controlled environment tests (including tests on<br />

plants <strong>and</strong> in vitro tests), <strong>and</strong> field trials. The outcome of a test was rated (+) if significant effect<br />

was reported, (0) if no significant efficacy was shown <strong>and</strong> (-) if the bio<strong>control</strong> agent stimulated<br />

disease development.<br />

*<br />

EU FR6 project 031499, funded in part by the European Commission<br />

2

Chapter 1<br />

To allow for the analysis of a large number of references, the abstracts were examined for the<br />

presence of the relevant data. The complete publications were acquired <strong>and</strong> examined only when<br />

the abstracts were not sufficiently precise.<br />

The data were collected in separate tables for each type of key target pest. For each table, they<br />

were sorted (in decreasing order of priority) according to the type <strong>and</strong> name of the bio<strong>control</strong><br />

agents, the specifically targeted pest, <strong>and</strong> the outcome of efficacy tests.<br />

In the third step, synthetic summary tables were constructed to quantify the number of different<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> compounds <strong>and</strong> microbial species <strong>and</strong> strains reported to have successful effect <strong>against</strong><br />

each type of key pathogen/disease or pest target.<br />

Results<br />

A total number of 1791 references were examined for key airborne diseases including powdery<br />

mildews, rusts, downy mildews (+ late blight of Potato/Tomato) <strong>and</strong> Botrytis <strong>and</strong> Monilia rots,<br />

together with soilborne diseases caused by Fusarium oxysporum (Table 2). Based on the<br />

examination of these references, successful effect in <strong>control</strong>led conditions was achieved for all<br />

targets under study with a variety of species <strong>and</strong> compounds (Appendices 1 to 6, Table 3).<br />

Table 2:<br />

Numbers of references on bio<strong>control</strong> examined per group of disease/plant pathogen.<br />

Target disease / plant<br />

pathogen<br />

Botrytis<br />

Relevance to<br />

ENDURE Case<br />

Studies<br />

OR, FV, GR*<br />

(postharvest)<br />

Number of<br />

references<br />

examined<br />

Period of<br />

publication<br />

examined<br />

880 1998-2008<br />

Powdery mildews all 166 1998-2008<br />

Rusts AC, FV, OR 154 1973-2008<br />

Downy mildews +<br />

Phytophthora infestans<br />

FV, GR, PO, TO 349 1973-2008<br />

Monilinia rot OR 194 1973-2008<br />

Fusarium oxysporum FV, TO 48 2007-2009<br />

*AC: Arable Crops; FV: Field Vegetables; GR: Grapes; OR: orchard; PO: Potato; TO: Tomato<br />

Concerning airborne diseases <strong>and</strong> pathogens, the largest number of reported successes was<br />

achieved with microbials, but there is a growing body of literature on plant <strong>and</strong> microbial extracts,<br />

as well as other types of substances (Table 3). On average, reports of success were far more<br />

numerous for experiments in <strong>control</strong>led conditions (in vitro or in planta) than for field trials.<br />

Very contrasted situations were also observed depending on the type of target<br />

disease/pathogen, with rare reports on the bio<strong>control</strong> of rusts <strong>and</strong> mildews compared to Botrytis,<br />

despite the fact that the literature was examined over a 35 year period for the former diseases <strong>and</strong><br />

only over the last 10 years for the latter.<br />

In total in this review, 157 species of micro-organisms have been reported for significant<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> activity. They belong to 36 genera of fungi or oomycetes, 13 of yeasts <strong>and</strong> 25 of<br />

bacteria. Among them, 29 species of fungi/oomycetes <strong>and</strong> 18 bacteria were reported as successful in<br />

the field <strong>against</strong> at least one of the five key airborne diseases included in this review (Table 4).<br />

3

Nicot et al.<br />

Table 3: Numbers of different bio<strong>control</strong> compounds <strong>and</strong> microbial species reported as having<br />

successful effect <strong>against</strong> key airborne pathogens/diseases of selected crops. Detailed<br />

information <strong>and</strong> associated bibliographic references are presented in Appendices 1 to 5<br />

Botanicals Microbials y Others z<br />

Target plant pathogen /<br />

laboratory<br />

laboratory<br />

laboratory<br />

disease<br />

tests x field trials<br />

tests x field trials<br />

tests x field trials<br />

Botrytis<br />

in vitro 26 - 31 b, 21 f - 7 -<br />

legumes 4 2 10 b, 12 f 3b, 9 f 0 0<br />

protected vegetables 0 1 22 b, 24 f 8 b, 9 f 5 1<br />

strawberry 0 0 14 b, 21 f 2 b, 13 f 7 1<br />

field vegetables 0 0 5 b, 15 f 2 f 0 0<br />

grapes 1 3 5 b, 27 f 5 b, 13 f 0 1<br />

pome/stone fruits 1 0 12 b, 35 f 2 b, 6 f 4 0<br />

others 3 0 15 b, 25 f 6 b, 6 f 0 0<br />

Powdery mildews<br />

Grape 1 1 4b; 10f 2b; 12f 3 2<br />

Arable crops 1 0 2b;9f 1b 5 0<br />

Strawberry 0 0 4b; 6f 0 0 0<br />

Cucurbitaceae 4 0 14b; 22f 4b; 9f 9 1<br />

Pome/stone fruits 0 0 3f 1f 0 0<br />

Pepper 1 0 4f 0 1 0<br />

Tomato 5 0 4b; 5f 1f; 1b 0 0<br />

Various 2 0 2b; 10f 1b; 1f 5 0<br />

Rusts<br />

arable crops 0 0 5 b, 6 f 2 b 2 0<br />

others 0 0 8 b, 13 f 0 1 0<br />

Downy mildews + late<br />

blight<br />

grapes 2 4 2 f 3 b, 2 f 2 3<br />

field vegetables 0 0 4 0 4 6<br />

potato 9 1 8 b, 10 f 5 b, 4 f 3 1<br />

tomato 2 1 5 b, 5 f 4 b 12 1<br />

Monilia rot<br />

in vitro 0 - 8 - 1 -<br />

pome fruit 0 0 7 0 0 0<br />

stone fruit 0 1 23b, 19 7b, 7f 2 2<br />

others 0 0 1b 2b, 1f 0 0<br />

x tests conducted in vitro <strong>and</strong>/or in planta in <strong>control</strong>led conditions<br />

y b: bacteria; f: fungi / oomycetes / yeasts<br />

z including culture filtrates <strong>and</strong> extracts from microorganisms<br />

4

Chapter 1<br />

Table 4:<br />

Microbial species of fungi/oomycetes, yeasts <strong>and</strong> bacteria reported to have a significant<br />

effect <strong>against</strong> five main types of airborne diseases or pathogens in laboratory conditions<br />

or in the field (yellow highlight). Bibliographic references are presented in Appendices 1<br />

to 5.<br />

A. Fungi <strong>and</strong> oomycetes<br />

Target disease / pathogen<br />

Microbial species<br />

Powdery<br />

Botrytis<br />

mildew<br />

Rust<br />

Acremonium spp.<br />

others<br />

cereals,<br />

Acremonium alternatum<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

A. cephalosporium grapes<br />

A. obclavatum others<br />

Alternaria spp. grapes cereals<br />

Downy mildew,<br />

late blight<br />

A. alternata others grapes<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

strawberry,<br />

Ampelomyces quisqualis<br />

protected<br />

vegetables,<br />

others,<br />

Aspergillus spp. others tomato<br />

A. flavus others<br />

Beauveria sp<br />

protected vegetables<br />

Botrytis cinerea nonaggressive<br />

strains<br />

legumes<br />

Chaetomium cochlioides<br />

grapes<br />

C. globosum legumes<br />

Cladosporium spp. flowers others<br />

C. chlorocephalum others<br />

C. cladosporioides flowers, legumes others<br />

C. oxysporum flowers others others<br />

C. tenuissimum strawberry<br />

field vegetables,<br />

others<br />

Monillia rot<br />

flowers, legumes,<br />

Clonostachys rosea<br />

others, strawberries,<br />

field vegetables,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

Coniothyrium spp.<br />

grapes<br />

C. minitans field vegetables<br />

Cylindrocladium<br />

others<br />

Drechslera hawaiinensis<br />

others<br />

Epicoccum sp<br />

flowers, grapes, field<br />

vegetables<br />

E. nigrum legumes, strawberries plum, peach<br />

E. purpurascens apple, cherry<br />

Filobasidium floriforme<br />

fruits<br />

Fusarium spp. flowers others<br />

F. acuminatum cereals<br />

F. chlamydosporum others<br />

F. oxysporum cereals tomato<br />

F. proliferatum grapes<br />

Galactomyces geotrichum<br />

fruits<br />

5

Nicot et al.<br />

Table 4 (continued)<br />

Gliocladium spp.<br />

grapes, protected<br />

vegetables, others<br />

G. catenulatum<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

legumes<br />

G. roseum<br />

flowers, grapes,<br />

legumes, others<br />

others<br />

blueberry<br />

G. virens<br />

strawberries, field<br />

vegetables<br />

potato, others<br />

G. viride protected vegetables<br />

Lecanicillium spp.<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

L. longisporum<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Meira geulakonigii<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Microdochium dimerum<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

Microsphaeropsis ochracea field vegetables<br />

Muscodor albus fruits, grapes peach<br />

Paecilomyces farinosus<br />

cereals<br />

P. fumorosoroseus<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Penicillium spp. fruits, field vegetables others potato, tomato<br />

P. aurantiogriseum legumes potato<br />

P. brevicompactum legumes<br />

P. frequentans plum, peach<br />

P. griseofulvum<br />

legumes, field<br />

vegetables<br />

P. purpurogenum peach<br />

P. viridicatum potato<br />

Phytophthora cryptogea<br />

potato<br />

grapes,<br />

Pseudozyma floculosa<br />

protected<br />

vegetables,<br />

Pythium olig<strong>and</strong>rum protected vegetables<br />

P. paroec<strong>and</strong>rum grapes<br />

P. periplocum grapes<br />

Rhizoctonia flowers potato<br />

Scytalidium<br />

grapes<br />

S. uredinicola others<br />

Sordaria fimicola<br />

apple<br />

Tilletiopsis spp.<br />

grapes<br />

T. minor others<br />

Trichoderma spp.<br />

flowers, grapes,<br />

legumes, strawberries,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

potato<br />

others<br />

T. asperellum strawberries<br />

T. atroviride legumes, strawberries peach<br />

T. hamatum flowers, legumes<br />

T. harzianum<br />

flowers, grapes,<br />

others,<br />

grapes, potato,<br />

legumes, strawberries,<br />

strawberry,<br />

tomato, field<br />

field vegetables,<br />

others<br />

protected<br />

vegetables,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

vegetables,<br />

others<br />

others<br />

cherry, peach<br />

T. inhamatum flowers<br />

T. koningii<br />

strawberries, field<br />

vegetables<br />

peach<br />

T. lignorum others<br />

6

Chapter 1<br />

Table 4 (continued)<br />

T. longibrachiatum strawberries<br />

T. polysporum strawberries apple<br />

T. taxi protected vegetables<br />

T. virens grapes<br />

T. viride<br />

fruits, grapes, legumes,<br />

strawberries, field others others potato, others peach<br />

vegetables, others<br />

Trichothecium<br />

grapes<br />

T. roseum grapes, legumes<br />

Ulocladium sp.<br />

grapes, field vegetables<br />

U. atrum<br />

flowers, grapes,<br />

strawberries, field<br />

vegetables, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

U. oudemansii grapes<br />

Ustilago maydis<br />

protected vegetables<br />

Verticillium grapes legumes<br />

V. chlamydosporium cereals<br />

V. lecanii strawberries<br />

cereals,<br />

protected<br />

vegetables,<br />

others<br />

legumes, others<br />

B. Yeasts<br />

Microbial species<br />

Botrytis<br />

Powdery<br />

mildew<br />

7<br />

Target disease / pathogen<br />

Rust<br />

Downy mildew,<br />

late blight<br />

Monillia rot<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

apple, cherry<br />

Aureobasidium pullulans strawberries, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

C<strong>and</strong>ida spp. tomato peach<br />

C. butyri fruits<br />

C. famata fruits<br />

C. fructus strawberries<br />

C. glabrata strawberries<br />

C. guilliermondii<br />

grapes, protected<br />

cherry<br />

vegetables<br />

C. melibiosica fruits<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

C. oleophila<br />

strawberries, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

C. parapsilosis fruits<br />

C. pelliculosa protected vegetables<br />

C. pulcherrima fruits, strawberries<br />

C. reukaufii strawberries<br />

C. saitoana fruits<br />

C. sake fruits<br />

C. tenuis fruits<br />

Cryptococcus albidus<br />

fruits, strawberries,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

C. humicola fruits<br />

C. infirmo-miniatus fruits cherry<br />

C. laurentii<br />

fruits, strawberries,<br />

cherry, peach<br />

protected vegetables<br />

Debaryomyces hansenii fruits, grapes cherry, peach<br />

Hanseniaspora uvarum grapes<br />

Kloeckera spp<br />

grapes<br />

K. apiculata fruits cherry, peach<br />

Metschnikowia fructicola<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

strawberries<br />

M. pulcherrima fruits apple, apricot<br />

Pichia anomala<br />

grapes, fruits

Nicot et al.<br />

Table 4 (continued)<br />

P. guilermondii<br />

fruits, strawberries,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

P. membranaefaciens grapes peach<br />

P. onychis field vegetables<br />

P. stipitis fruits<br />

Rhodosporidium diobovatum protected vegetables<br />

R. toruloides fruits<br />

Rhodotorula<br />

peach<br />

flowers, fruits,<br />

R. glutinis<br />

strawberries, protected field vegetables,<br />

vegetables<br />

R. graminis flowers<br />

R. mucilaginosa flowers<br />

R. rubra protected vegetables<br />

Saccharomyces cerevisiae fruits<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Sporobolomyces roseus fruits<br />

Trichosporon sp.<br />

fruits<br />

T. pullulans<br />

fruits, grapes, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

C. Bacteria<br />

Microbial species<br />

Acinetobacter lwoffii<br />

Azotobacter<br />

Bacillus spp.<br />

B. amyloliquefaciens<br />

Botrytis<br />

grapes<br />

grapes, strawberry,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

others<br />

arable crops, flowers,<br />

fruits, field vegetables,<br />

Powdery<br />

mildew<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Target disease / pathogen<br />

Rust<br />

others<br />

Downy<br />

mildew, late<br />

blight<br />

other<br />

potato, field<br />

vegetables<br />

protected vegetables<br />

B. cereus flowers, legumes others tomato<br />

B. circulans protected vegetables<br />

B. lentimorbus others<br />

B. licheniformis<br />

fruits, strawberry,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

B. macerans legumes<br />

B. marismortui strawberry<br />

B. megaterium legumes, others<br />

B. pumilus fruits, strawberry tomato, others<br />

B. subtilis<br />

flowers, fruits, grapes,<br />

legumes, strawberry,<br />

field vegetables,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

B. thuringiensis strawberry<br />

Bakflor (consortium of<br />

valuable bacterial<br />

protected vegetables<br />

physiological groups)<br />

Brevibacillus brevis<br />

field vegetables,<br />

protected vegetables<br />

cereals,<br />

grapes,<br />

strawberry,<br />

protected<br />

vegetables,<br />

others<br />

grapes,<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

legumes<br />

grapes, potato,<br />

others<br />

grapes<br />

Monillia rot<br />

apricot<br />

peach<br />

apricot,<br />

blueberry,<br />

cherry, peach<br />

Burkholderia spp.<br />

tomato<br />

B. cepacia protected vegetables cherry<br />

B. gladii apricot<br />

B. gladioli flowers<br />

Cedecea dravisae<br />

others<br />

Cellulomonas flavigena<br />

tomato<br />

8

Chapter 1<br />

Table 4 (continued)<br />

Cupriavidus campinensis<br />

Enterobacter cloacae<br />

grapes, protected<br />

vegetables, others<br />

Enterobacteriaceae<br />

strawberry<br />

Erwinia<br />

fruits, others<br />

Halomonas sp.<br />

strawberry, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

H. subglaciescola protected vegetables<br />

Marinococcus halophilus protected vegetables<br />

Salinococcus roseus<br />

protected vegetables<br />

Halovibrio variabilis protected vegetables<br />

Halobacillus halophilus protected vegetables<br />

H. litoralis protected vegetables<br />

H. trueperi protected vegetables<br />

Micromonospora coerulea protected vegetables<br />

Paenibacillus polymyxa<br />

strawberry, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

Pantoea spp.<br />

grapes, protected<br />

vegetables<br />

P. agglomerans<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

legumes, strawberry<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

9<br />

legumes<br />

potato<br />

apple, apricot,<br />

blueberry,<br />

cherry, peach,<br />

plum<br />

Pseudomonas spp.<br />

flowers, fruits, grapes,<br />

potato, tomato,<br />

others<br />

field vegetables<br />

field vegetables<br />

apricot<br />

P. aeruginosa protected vegetables<br />

P. aureofasciens cereals cherry<br />

P. cepacia strawberry peach<br />

P. chlororaphis strawberry cherry<br />

P. corrugata peach<br />

P. fluorescens<br />

P. putida<br />

fruits, grapes,<br />

legumes, strawberry,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

others<br />

flowers, legumes,<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

others<br />

cereals, ,<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

others<br />

P. syringae<br />

fruits, strawberry, field<br />

vegetables<br />

grapes<br />

P. reactans strawberry<br />

P. viridiflava fruits<br />

Rhanella spp.<br />

R aquatilis<br />

fruits<br />

Serratia spp.<br />

S. marcescens flowers<br />

S. plymuthica protected vegetables<br />

Stenotrophomonas<br />

maltophilia<br />

Streptomyces spp.<br />

S. albaduncus legumes<br />

S. ahygroscopicus protected vegetables<br />

S. exfoliatus legumes<br />

S. griseoplanus legumes<br />

S. griseoviridis<br />

protected vegetables,<br />

others<br />

S. lydicus protected vegetables<br />

S. violaceus legumes<br />

Virgibacillus marismortui strawberry<br />

Xenorhabdus bovienii<br />

X. nematophilus<br />

protected<br />

vegetables<br />

legumes<br />

cereals<br />

legumes<br />

grapes, potato,<br />

tomato, others<br />

potato<br />

potato<br />

tomato<br />

potato<br />

blueberry,<br />

cherry<br />

apple, peach

Nicot et al.<br />

One striking aspect of this inventory is that although the five target diseases / pathogens<br />

included in our review are airborne <strong>and</strong> affect mostly the plant canopy, the vast majority of cited<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> microorganisms are soil microorganisms. The scarcity of bio<strong>control</strong> agents originating<br />

from the phyllosphere could be due to actual lack of effectiveness, or it could be the result of a bias<br />

by research groups in favour of soil microbes when they gather c<strong>and</strong>idate microorganisms to be<br />

screened for bio<strong>control</strong> activity. This question would merit further analysis as it may help to devise<br />

improved screening strategies. As "negative" results (the lack of effectiveness of tested<br />

microorganisms, for example) are seldom published, the completion of such an analysis would in<br />

turn necessitate direct information from research groups who have been implicated in screening for<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> agents, or the development of a specific screening experiment comparing equal numbers<br />

of phyllosphere <strong>and</strong> of soil microbial c<strong>and</strong>idates.<br />

Another striking aspect is that most of the beneficial micro-organisms inventoried in this study<br />

(49 fungi/oomycetes, 28 yeasts <strong>and</strong> 41 bacteria) are cited only for bio<strong>control</strong> of one of the five types<br />

of airborne diseases included in the survey (Figure 2). However, several species clearly st<strong>and</strong> out<br />

with a wide range of effectiveness, as they were successfully used <strong>against</strong> all five types of target<br />

diseases on a variety of crops. This includes the fungi Trichoderma harzianum <strong>and</strong> Trichoderma<br />

viride (2 of 12 species of Trichoderma reported as bio<strong>control</strong>-effective in the reviewed literature)<br />

<strong>and</strong> the bacteria Bacillus subtilis <strong>and</strong> Pseudomonas fluorescens.<br />

Number of species<br />

50<br />

45<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

fungi / oomycetes<br />

yeasts<br />

bacteria<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Number of <strong>control</strong>led target diseases / pathogens<br />

Figure 2:<br />

Range of efficacy of 157 microbial bio<strong>control</strong> agents <strong>against</strong> five main types of airborne<br />

diseases. Detailed data are presented in Table 4.<br />

Concerning Fusarium oxysporum. A data base interrogation with the key words “Fusarium<br />

oxysporum AND <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>” provided 2266 for the period 1973-2009. Using these key<br />

words we did not select only papers regarding <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of diseases induced by F.<br />

oxysporum but also all the paper dealing with the use of strains of F. oxysporum to <strong>control</strong> diseases<br />

<strong>and</strong> weeds. There are quite many papers dealing with the use of different strains of F. oxysporum to<br />

<strong>control</strong> Broom rape (orobanche) <strong>and</strong> also the use of F. oxysporum f. sp. erythroxyli to eradicate<br />

coca crops.<br />

We decided to limit our review to the two last years <strong>and</strong> to concentrate on references for which<br />

full text was available on line. Finally we reviewed 48 papers. All these papers were dealing with<br />

the selection <strong>and</strong> development of micro-<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> agents; only two were considering others<br />

methods. One was addressing the use of chemical elicitors to induce resistance in the plant; the<br />

10

Chapter 1<br />

other was aiming at identifying the beneficial influence of non-host plant species either used in<br />

rotation or in co-culture. Based on this very limited number of papers the formae speciales of F.<br />

oxysporum the most frequently studied was F.o. f. sp. lycopersici (17 studies). Other included f. spp.<br />

melonis, ciceris, cubense, niveum <strong>and</strong> cucumerinum. The antagonists studied included Bacillus spp<br />

<strong>and</strong> Paenibacillus (16 papers), Trichoderma spp. (14 papers), fluorescent Pseudomonads (7 papers),<br />

Actinomycetes (5 papers), non pathogenic strains of F. oxysporum (5 papers), mycorrhizal fungi<br />

<strong>and</strong> Penicillium.<br />

Most of the publications (28) reported on in vitro studies. Among them a few concerned the<br />

mechanisms of action of the antagonists, the others just related screening studies using plate<br />

confrontation between the antagonists <strong>and</strong> the target pathogens. In most of these papers (22) the in<br />

vitro screening was followed by pot or greenhouse experiments aimed at demonstrating the capacity<br />

of the antagonist to reduce disease severity or disease incidence after artificial inoculation of the<br />

pathogen. Finally only 9 publications report results of field experiments. Most of these papers<br />

concluded on the promising potential of the selected strains of antagonists able to decrease disease<br />

incidence or severity by 60 to 90%. Generally speaking, this limited literature review showed that<br />

most of the lab studies are not followed by field studies. There is a need for implementation of<br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in the fields.<br />

Identified knowledge gaps<br />

Several types of knowledge gaps were identified in this review. They include:<br />

- the near absence of information on bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> diseases of certain important European<br />

crops such as winter arable crops.<br />

- the scarcity of reports on bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> several diseases of major economic importance on<br />

numerous crops, such as those caused by obligate plant pathogens (rusts, powdery mildews,<br />

downy mildews)<br />

- the still limited (but increasing) body of detailed knowledge on specific mechanisms of action<br />

<strong>and</strong> their genetic determinism. The little knowledge available at the molecular level is<br />

concentrated on few model bio<strong>control</strong> agents such as Trichoderma <strong>and</strong> Pseudomonas.<br />

- the still very limited information on secondary metabolites produced by microbial bio<strong>control</strong><br />

agents<br />

- the lack of underst<strong>and</strong>ing for generally low field efficacy of resistance-inducing compounds<br />

- the lack of knowledge on variability in the susceptibility of plants pathogens to the action of<br />

BCAs <strong>and</strong> on possible consequences for field efficacy <strong>and</strong> its durability.<br />

References<br />

Due to their high number, the references used in this chapter are presented, together with<br />

summary tables, in Appendices 1 to 6.<br />

11

Chapter 2<br />

Potential of <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

2. Beneficials for <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> insect pests.<br />

The grapevine case study<br />

Massimo Giorgini<br />

CNR, Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante, via Università 133, 80055 Portici (NA), Italy<br />

Bibliographic survey on <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>against</strong> arthropod pests in<br />

selected crops<br />

We carried out a preliminary bibliographic survey to quantify the literature on <strong>augmentative</strong><br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of pests published from 1973 to 2008. The survey was restricted to crops relevant<br />

to case studies of ENDURE. They included grapevine; orchards: apple <strong>and</strong> pear; arable crops: corn<br />

<strong>and</strong> wheat; field vegetables: carrot <strong>and</strong> onion. Augmentative <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> (Van Driesche &<br />

Bellows, 1996) comprises of inoculative augmentation (<strong>control</strong> being provided by the offspring of<br />

released organisms) <strong>and</strong> inundative augmentation (<strong>control</strong> expected to be performed by the<br />

organisms released, with little or no contribution by their offspring).<br />

Our bibliographic survey was conducted by using the CAB Abstracts database by entering the<br />

name of each crop <strong>and</strong> one key word selected from the following list in order to retrieve the<br />

maximum number of references. For each selected crop, the key words used for the bibliographic<br />

survey were: a) <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>; b) augmentation <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>; c) inoculative<br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>; d) inundative <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>. The survey with these key words produced a<br />

very low number of results all of which were examined. For this reason we added two key words<br />

that were more general: e) insects <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>; f) mites <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>. For the searching<br />

criteria a to d, total records will be examined. In this case, given the extremely high number of<br />

records, only references within the period 1998-2008 were examined to select only the publications<br />

concerning the <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>. The results of this survey are reported in Appendix<br />

7.<br />

The analytical review of the scientific literature on <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong>, presented<br />

in the rest of this chapter, was then focused on grapevine.<br />

Status of researches on augmentation of natural enemies to <strong>control</strong> arthropod pests in<br />

grapevine<br />

The references extracted from the CAB Abstracts database, following the criteria described in the<br />

previous paragraph, were examined to identify those concerning the use of natural enemies in<br />

augmentation <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in grapevine. The abstracts of 607 references were examined <strong>and</strong><br />

only 70 papers reported data on application <strong>and</strong> efficiency of <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> (Table 5).<br />

12

Chapter 2<br />

Table 5:<br />

References extracted from the CAB Abstracts database <strong>and</strong> examined for reviewing<br />

augmentation <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in grapevine.<br />

Key words<br />

Total records 1998-2008<br />

(1973-2008)<br />

Augmentative <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 7 6<br />

Augmentation <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 10 6<br />

Inoculative <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 4 1<br />

Inundative <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 7 3<br />

Insects <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 373<br />

Mites <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> 190<br />

Total references examined 28 579<br />

Total references showing data on<br />

70<br />

<strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong><br />

The survey includes records for grapevine, grape <strong>and</strong> vineyard.<br />

Results<br />

Very few papers (62) on <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> in grapevine have been published during the period 1998-2008, with<br />

an average of 5.6 publications per year. Most references (93.5%) showed data on <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of insects <strong>and</strong> only<br />

4 papers on the <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of mites were published (Figure 3).<br />

Figure 3:<br />

Number of papers per year published during 1998-2008 concerning <strong>augmentative</strong><br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of pests in grapevine.<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> of insect pests<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> of mite pests<br />

The data extracted from the abstracts of the selected references were collected analytically in<br />

separate tables for each group of bio<strong>control</strong> agents (Appendix 8) <strong>and</strong> references were sorted<br />

chronologically (starting from the eldest). For each species of bio<strong>control</strong> agent, target species of<br />

pest, Country, type of augmentation (inundative, inoculative), type of test (laboratory, field),<br />

efficacy of bio<strong>control</strong>, additional information <strong>and</strong> results were reported.<br />

13

Giorgini<br />

Data reported in Appendix 8 were summarized in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Figure 4 <strong>and</strong><br />

Figure 5. A list of the bio<strong>control</strong> agents used in <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> in grapevine is<br />

reported in Table 6 <strong>and</strong> Figure 4. A list of groups <strong>and</strong> species of the targeted pests <strong>and</strong> the<br />

antagonists used for their <strong>control</strong> is reported in Table 7 <strong>and</strong> Figure 5; the efficacy of bio<strong>control</strong><br />

agents is reported in Table 8.<br />

The group of pests on which the highest number of researches on <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> has<br />

been carried out is Lepidoptera (60% of total references) with the family Tortricidae representing<br />

the main target (55%) (Figure 5) including the grape berry moths key pests Lobesia botrana <strong>and</strong><br />

Eupecilia ambiguella (Table 7). Bacillus thuringiensis has resulted the most frequently used<br />

bio<strong>control</strong> agent <strong>against</strong> Lepidoptera by achieving an effective <strong>control</strong> of different targets in<br />

different geographic areas (Table 7, Table 8, Appendix 8.7). We sorted 28 references (39% of the<br />

total citations) dealing with the use of B. thuringiensis of which 23 references were referred to the<br />

<strong>control</strong> of L. botrana. The augmentation of egg parasitoids of the genus Trichogramma<br />

(Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) resulted the alternative strategy to B. thuringiensis to <strong>control</strong><br />

Lepidoptera Tortricidae (13 references, 16% of total citations) (Table 7, Table 8). Field evaluations<br />

indicated T. evanescens as a promising bio<strong>control</strong> agent of L. botrana (El-Wakeil et al., 2008 in<br />

Appendix 8.1).<br />

Fewer researches were carried out on <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> of other group of pests. First in<br />

the list were mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) (9 references, 13% of the total citations). In<br />

field evaluations (4 papers) parasitoid wasps of the family Encyrtidae have resulted extremely<br />

active <strong>and</strong> promising to be used in <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> of mealybugs (Appendix 8.2).<br />

Antagonists used in <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> in grapevine were mainly represented by insect<br />

pathogens (59% of the total citations), including the bacterium B. thuringiensis, fungi <strong>and</strong><br />

nematodes (Figure 4, Table 6). Beside the efficacy of B. thuringiensis, promising results were<br />

obtained from researches in the <strong>control</strong> of the grape phylloxera Daktulosphaira vitifolie, a gallforming<br />

aphid, by soil treatments with the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae (Table 8, Appendix 8.5).<br />

Once <strong>control</strong>led by grafting European grape cultivars onto resistant rootstocks, the grape phylloxera<br />

has gone to resurgence in commercial vineyards worldwide <strong>and</strong> new <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> strategy<br />

could be necessary to complement the use of resistant rootstocks <strong>and</strong> to avoid the distribution of<br />

chemical insecticides in the soil.<br />

Entomophagous arthropods, including parasitoid wasps <strong>and</strong> predators represented 41% of the<br />

total citations (Figure 4, Table 6). Best results were obtained from researches on parasitoids (18<br />

references), namely the use of Trichogrammatidae <strong>and</strong> Encyrtidae in <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> of<br />

grape moths (Tortricidae) <strong>and</strong> mealybugs (Pseudococcidae) respectively (Table 7, Table 8,<br />

Appendix 8.1 <strong>and</strong> 8.2). Among predators, augmentation of Phytoseiidae mites has produced some<br />

positive results in <strong>control</strong>ling spider mites <strong>and</strong> eriophyid mites on grape (Table 7, Table 8,<br />

Appendix 8.3).<br />

Brief considerations<br />

Key pests of grapevine like L. botrana <strong>and</strong> E. ambiguella can be <strong>control</strong>led effectively with<br />

<strong>augmentative</strong> strategies that rely on the use of B. thuringiensis. To date, formulations of B.<br />

thuringiensis are currently used in IPM strategies. The specificity of B. thuringiensis could be a<br />

problem in those vineyards where other pests can reach the status of economically importance, if<br />

not <strong>control</strong>led by indigenous <strong>and</strong>/or introduced natural enemies. Researches on <strong>augmentative</strong><br />

bio<strong>control</strong> should be implemented in order to develop new strategies to solve problems related to<br />

emerging pests <strong>and</strong> alternatives to B. thuringiensis if resistant strains should appear in target<br />

species.<br />

References<br />

Due to their high number, the references for this chapter are presented in Appendix 8.<br />

14

Chapter 2<br />

Table 6:<br />

Bio<strong>control</strong> agents evaluated in researches on <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> of pests in<br />

grapevine.<br />

Target pests <strong>and</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> agents<br />

References<br />

before 1998<br />

References<br />

1998-2008<br />

Number of<br />

citations<br />

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF INSECTS<br />

Bacteria<br />

[1 species: 2 subspecies]<br />

0 28<br />

- Bacillus thuringiensis<br />

28<br />

(subsp. kurstaki, subsp. aizawai)<br />

Fungi [5 species] 0 10<br />

- Metarhizium anisopliae 7<br />

- Beauveria bassiana 2<br />

- Beauveria brongniartii 1<br />

- Verticillium lecanii 1<br />

- Clerodendron inerme 1<br />

Nematodes [5 species] 1 3<br />

- Steinernema spp. 2 spp. 2<br />

- Heterorabditis spp. 3 spp. 3<br />

Parasitoid Hymenoptera [15 species] 2 16<br />

- Trichogramma spp. (Trichogrammatidae) 10 spp 13<br />

- Coccidoxenoides spp. (Encyrtidae) 2 spp. 2<br />

- Anagyrus spp. (Encyrtidae) 2 spp. 3<br />

- Muscidifurax raptor (Pteromalidae) 1 spp. 1<br />

Predators [5 species] 2 4<br />

- Chrysoperla (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) 3 spp. 3<br />

- Cryptolaemus montrouzieri<br />

2<br />

(Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)<br />

- Nephus includens (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) 1<br />

BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF MITES<br />

Predators (Acari: Phytoseiidae) [4 species]<br />

2 4<br />

- Typhlodromus pyri 5<br />

- Kampimodromus aberrans 2<br />

- Amblyseius <strong>and</strong>ersoni 1<br />

- Phytoseiulus persimilis 1<br />

15

Giorgini<br />

Table 7:<br />

Number of references on <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> agents per group <strong>and</strong> species of target pest in grapevine.<br />

Pest References Bacillus<br />

thuringiensis<br />

(2 subspecies)<br />

Trichogramma<br />

(10 species)<br />

other<br />

parasitoids<br />

(5 species)<br />

Predators of<br />

mites<br />

Acari:<br />

Phytoseidae<br />

(4 species)<br />

Predators of<br />

insects<br />

Coleoptera:<br />

Coccinellidae<br />

(2 species)<br />

Predators of<br />

insects<br />

Neuroptera:<br />

Chrysopidae<br />

(3 species)<br />

Fungi<br />

(5 species)<br />

Nematodes<br />

(5 species)<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

39<br />

Tortricidae<br />

Lobesia botrana<br />

28 23 5<br />

(grape berry moth)<br />

Eupoecilia ambiguella<br />

6 3 3<br />

(grape berry moth)<br />

Epiphyas postvittana<br />

3 3<br />

(light brown apple moth)<br />

Argyrotaenia sphaleropa 3 1 2<br />

(South American tortricid moth)<br />

Bonagota cranaodes<br />

2 2<br />

(Brasilian apple leafroller)<br />

Endopiza viteana<br />

2 2<br />

(grape berry moth)<br />

Sparganothis pilleriana 1 1<br />

(grape leafroller)<br />

Epichoristodes acerbella 1 1<br />

(South African carnation tortrix)<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

1<br />

Pyralidae<br />

Cryptoblabes gnidiella<br />

1 1<br />

(honey moth)<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

1<br />

Arctiidae<br />

Hyphantria cunea<br />

1<br />

(fall webworm)<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

2<br />

Sesiidae<br />

Vitacea polistiformis 2 2<br />

16

Table 7 (continued)<br />

Chapter 2<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

9<br />

Pseudococcidae<br />

Planococcus ficus 6 4<br />

2<br />

Encyrtidae<br />

Pseudococcus maritimus 1 1<br />

Pseudococcus longispinus 1<br />

Maconellicoccus hirsutus 1<br />

1<br />

Encyrtidae<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

3<br />

Cicadellidae<br />

Erythroneura variabilis 3 3<br />

Erythroneura elegantula 3 3<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

5<br />

Phylloxeridae<br />

Daktulosphaira vitifoliae<br />

4 1<br />

(grape phylloxera)<br />

Diptera:<br />

1<br />

Tephritidae<br />

Ceratitis capitata 1 1<br />

Pteromalidae<br />

Coleoptera:<br />

2<br />

Scarabeidae<br />

Melolontha melolontha 2 1 1<br />

Thysanoptera:<br />

3<br />

Thripidae<br />

Frankliniella occidentalis 2 2<br />

grape thrips 1 1<br />

Acari:<br />

6<br />

Tetranichidae<br />

Panonychus ulmi 5 5<br />

Tetranychus urticae 1 1<br />

Tetranychus kanzawai 1 1<br />

Eotetranychus carpini 2 2<br />

Acari:<br />

2<br />

Eriophyidae<br />

Calepitrimerus vitis 1 1<br />

Calomerus vitis 1 1<br />

17

Giorgini<br />

Table 8:<br />

Number of references reporting data on the efficacy of <strong>augmentative</strong> bio<strong>control</strong> of<br />

pests in grapevine.<br />

Groups of Pests Bio<strong>control</strong> agents Total<br />

number of<br />

references<br />

Number of references reporting data<br />

on efficacy in pest <strong>and</strong> related<br />

damage <strong>control</strong> *<br />

Laboratory assays Field evaluation<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

Tortricidae<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

Pyralidae<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

Arctiidae<br />

Lepidoptera:<br />

Sesiidae<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

Pseudococcidae<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

Cicadellidae<br />

Hemiptera:<br />

Phylloxeridae<br />

Diptera:<br />

Tephritidae<br />

Acari:<br />

Tetranichidae<br />

Acari:<br />

Eriophyidae<br />

Coleoptera:<br />

Scarabeidae<br />

Thysanoptera:<br />

Thripidae<br />

Bacillus thuringiensis 26 2 + 16 +<br />

1 -<br />

Trichogramma spp.<br />

parasitoids<br />

13<br />

1 -<br />

9 +<br />

1 -<br />

Bacillus thuringiensis 1 1 +<br />

Bacillus thuringiensis 1 1 +<br />

Nematodes 2 2 + 1 +<br />

1 + (greenhouse)<br />

Encyrtidae parasitoids 5 4 +<br />

Coccinellidae 3 1 + (greenhouse)<br />

Fungi 1 1 +<br />

Chrysopidae 3 2 -<br />

Nematodes 1 1 +<br />

Fungi 5 1 + 2 +<br />

1 -<br />

Pteromalidae parasitoids 1 1 + 1 +<br />

Phytoseidae 6 4 +<br />

Phytoseidae 2 1 +<br />

Nematodes 1 1 +<br />

Fungi 1 1 +<br />

Fungi 3 1 + 2 +<br />

* + means effective, - means not effective bio<strong>control</strong> agent<br />

18

Chapter 2<br />

Bacillus thuringiensis: 28 (39%)<br />

Fungi: 10 (14%)<br />

Nematodes: 4 (6%)<br />

Parasitoid Hymenoptera: 18 (25%)<br />

Predators of insects (Chrysopidae,<br />

Coccinellidae): 6 (8%)<br />

Predators of mites (Phytoseidae): 6 (8%)<br />

Figure 4:<br />

Groups of bio<strong>control</strong> agents investigated in <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

researches in grapevine. Number of references for each group is reported.<br />

Lepidoptera Tortricidae: 39 (55%)<br />

Lepidoptera Sesiidae: 2 (3%)<br />

Lepidoptera Arctiidae: 1 (1%)<br />

Lepidoptera Pyralidae: 1 (1%)<br />

Hemiptera Pseudococcidae: 9 (13%)<br />

Hemiptera Phylloxeridae: 5 (7%)<br />

Hemiptera Cicadellidae: 3 (4%)<br />

Acari Tetranichidae <strong>and</strong> Eriophyidae: 6 (8%)<br />

Thysanoptera Thripidae: 3 (4%)<br />

Coleoptera Scarabeidae: 2 (3%)<br />

Diptera Tephritidae: 1 (1%)<br />

Figure 5:<br />

Groups of target pests investigated in <strong>augmentative</strong> <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> researches<br />

in grapevine. Number of references for each group is reported.<br />

19

Chapter 3<br />

Potential of bio<strong>control</strong> based on published research.<br />

3. Research <strong>and</strong> Development in classical <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> with<br />

emphasis on the recent introduction of insect parasitoids<br />

Nicolas Ris <strong>and</strong> Jean Claude Malausa<br />

INRA, UE 1254, Unité expérimentale de Lutte Biologique, Centre de recherche PACA,<br />

400 route des Chappes, BP 167, F-06903 Sophia Antipolis, France<br />

Scope of the review<br />

Defined as “the intentional introduction of an exotic, usually co-evolved, <strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong><br />

agent [hereafter BCA] for permanent establishment <strong>and</strong> long-term pest <strong>control</strong>’, classical<br />

<strong>biological</strong> <strong>control</strong> [hereafter ClBC] is a pest <strong>control</strong> strategy that has crystallized numerous<br />

studies since more than one century <strong>and</strong> provided numerous efficient solutions for pest<br />

<strong>control</strong>. The main advantages <strong>and</strong> risks of this strategy can be summarized as follows. In a<br />

context of the globalisation of international trade <strong>and</strong> human mobility, an ever growing<br />

number of exotic pests emerge locally. Such species can rapidly pullulate <strong>and</strong> jeopardize<br />

cultural practices. This general trend can also be favoured by global climatic changes that<br />

may allow the development of agronomic pests beyond their initial distribution area <strong>and</strong><br />