Prairie Sandreed Plant Guide - Plant Materials Program

Prairie Sandreed Plant Guide - Plant Materials Program

Prairie Sandreed Plant Guide - Plant Materials Program

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PRAIRIE SANDREED<br />

Calamovilfa longifolia (Hook.)<br />

Scribn.<br />

<strong>Plant</strong> Symbol = CALO<br />

Contributed by: USDA NRCS Bismarck, North<br />

Dakota and Manhattan, Kansas <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Materials</strong><br />

Centers<br />

<strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><br />

while available carbohydrates increase from 45<br />

percent in May to 55 percent in November (Craig,<br />

2002). <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is usually considered a<br />

decreaser with grazing pressure, but will initially<br />

increase under heavy grazing use, especially if<br />

growing within a big bluestem/sand bluestem plant<br />

community. <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed generally is seeded as a<br />

component of a native mix for range seeding on<br />

sandy sites.<br />

Wildlife Value: <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed provides fair forage<br />

for grazing and browsing wildlife in early spring and<br />

summer. The plant becomes more important in late<br />

fall and winter as the plant cures well on the stem and<br />

provides upright and accessible forage. Seed is used<br />

by songbirds and small rodents.<br />

Erosion Control: The rhizomatous growth habit and<br />

extensive fibrous root system of prairie sandreed<br />

makes it an excellent species for stabilization of<br />

sandy sites. On the shores of the Great Lakes it<br />

provides wind erosion control, dune stabilization, and<br />

water quality improvement.<br />

Status<br />

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State<br />

Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s<br />

current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species,<br />

state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).<br />

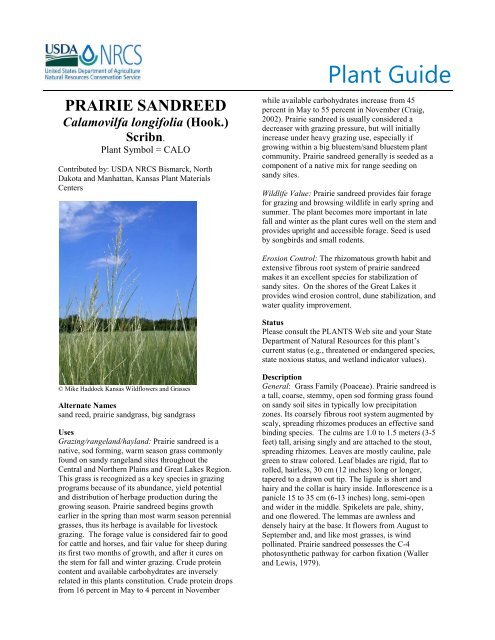

© Mike Haddock Kansas Wildflowers and Grasses<br />

Alternate Names<br />

sand reed, prairie sandgrass, big sandgrass<br />

Uses<br />

Grazing/rangeland/hayland: <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is a<br />

native, sod forming, warm season grass commonly<br />

found on sandy rangeland sites throughout the<br />

Central and Northern Plains and Great Lakes Region.<br />

This grass is recognized as a key species in grazing<br />

programs because of its abundance, yield potential<br />

and distribution of herbage production during the<br />

growing season. <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed begins growth<br />

earlier in the spring than most warm season perennial<br />

grasses, thus its herbage is available for livestock<br />

grazing. The forage value is considered fair to good<br />

for cattle and horses, and fair value for sheep during<br />

its first two months of growth, and after it cures on<br />

the stem for fall and winter grazing. Crude protein<br />

content and available carbohydrates are inversely<br />

related in this plants constitution. Crude protein drops<br />

from 16 percent in May to 4 percent in November<br />

Description<br />

General: Grass Family (Poaceae). <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is<br />

a tall, coarse, stemmy, open sod forming grass found<br />

on sandy soil sites in typically low precipitation<br />

zones. Its coarsely fibrous root system augmented by<br />

scaly, spreading rhizomes produces an effective sand<br />

binding species. The culms are 1.0 to 1.5 meters (3-5<br />

feet) tall, arising singly and are attached to the stout,<br />

spreading rhizomes. Leaves are mostly cauline, pale<br />

green to straw colored. Leaf blades are rigid, flat to<br />

rolled, hairless, 30 cm (12 inches) long or longer,<br />

tapered to a drawn out tip. The ligule is short and<br />

hairy and the collar is hairy inside. Inflorescence is a<br />

panicle 15 to 35 cm (6-13 inches) long, semi-open<br />

and wider in the middle. Spikelets are pale, shiny,<br />

and one flowered. The lemmas are awnless and<br />

densely hairy at the base. It flowers from August to<br />

September and, and like most grasses, is wind<br />

pollinated. <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed possesses the C-4<br />

photosynthetic pathway for carbon fixation (Waller<br />

and Lewis, 1979).

Distribution: For current distribution, please consult<br />

the <strong>Plant</strong> Profile page for this species on the<br />

PLANTS Web site.<br />

Habitat: <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is native from Manitoba to<br />

Quebec, Canada and south to Idaho, Colorado,<br />

Kansas and Indiana. Optimal performance can be<br />

expected on a sandy textured soil in the 40 to 50 cm<br />

(16-20 inch) rainfall zone. It exhibits strong drought<br />

tolerance when well established. It is intolerant of<br />

high water tables and early spring flooding.<br />

Steve Hurst, From PLANTS, provided by ARS Systematic Botany<br />

and Mycology Laboratory.<br />

Adaptation<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is drought tolerant and adapted to<br />

mean annual precipitation of less than 25 cm up to 50<br />

cm (10-20 inches). It is predominately found growing<br />

in clumps or colonies on coarse or sandy soil types. It<br />

will grow on soils that are somewhat alkaline, but it<br />

is not tolerant to salt. <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed occurs<br />

naturally in mixed native stands with sand bluestem<br />

Andropogon hallii, little bluestem Schizachyrium<br />

scoparium, and sand lovegrass Eragrostis trichodes<br />

on choppy sand range sites. Several shrubs, including<br />

yucca Yucca glauca and sand sage Artemisia filifolia<br />

and a variety of forbs occur intermixed on these sites.<br />

It has been found growing on blow out sites in the<br />

Nebraska Sandhills.<br />

Establishment<br />

Propagation of Calamovilfa longifolia is<br />

accomplished by seed and vegetative means. Maun<br />

(1981) studied germination and seedling<br />

establishment on Lake Huron sand dunes at Pinery<br />

Provincial Park, Ontario. Seedling establishment is<br />

considered risky on sand dunes where high soil<br />

surface temperatures, low nutrient supply, low<br />

moisture availability, and erosion can limit seedling<br />

establishment and growth. Maun (1981) found that<br />

Calamovilfa longifolia produces large numbers of<br />

intermediate size seed (mean seed weight 1.64 mg +<br />

.14 mg standard deviation). He further noted that the<br />

endosperm of sandreed exhibited a dimorphic color<br />

scheme (brown and white) and that the brown<br />

endosperm types were significantly heavier than the<br />

white types. Maun’s (1981) seed germination studies<br />

indicated that the best germinations of Calamovilfa<br />

were produced when growth chamber settings were<br />

25 degrees C (14 hours) and 10 degrees C (10 hours).<br />

Temperatures higher (35 and 20 degrees C) and<br />

lower (15 and 0 degrees C) than those reduced<br />

germination significantly. Stratification of sandreed<br />

seed did not improve total germination, but it<br />

produced a faster rate of germination overall.<br />

Maun and Riach (1981) studied sand deposition<br />

effects on seedling emergence at field sites and<br />

greenhouse plantings. They found that seedling<br />

emergence from greater than 8.0 cm (3 inch) depths<br />

was not probable. Excavation of sites with seed<br />

buried by more than 8 cm (3 inch) of sand indicated<br />

that seed had germinated, but failed to emerge from<br />

that depth. Thus seedling emergence was negatively<br />

correlated with planting depth. Therefore, planting of<br />

prairie sandreed should be accomplished with a drill<br />

equipped with depth bands to better control depth of<br />

seeding. Seed should be planted at a depth of 2.54 cm<br />

(1 inch) on coarse textured soils and 1.27 cm (1/2<br />

inch) or less on medium to fine textured soils.<br />

Seedbed preparation should provide a weed free, firm<br />

surface on which to plant. Seedling vigor is only fair<br />

and stands develop rather slowly. Stands may require<br />

as long as two to three years to fully develop.<br />

Seeding rate will vary by region and may be<br />

influenced by the amount of processing provided by<br />

the seed producer. Some seed vendors process the<br />

seed down to the bare caryopsis. This will influence<br />

the seeding rate that is utilized.<br />

Management<br />

Mullahey et al. (1991) found that a June and August<br />

defoliation of prairie sandreed over a three year<br />

period produced the greatest dry matter yield<br />

compare to other treatments and the control.<br />

Generally annual dry matter yields declined for all<br />

defoliation treatments and the control during the three<br />

year study. Burlaff (1971) concluded that the<br />

concentration of crude protein in prairie sandreed<br />

declined with increased maturity of the forage. Dry<br />

matter digestibility also declined with advanced<br />

maturity of the plants. In similar studies Cogswell<br />

and Kamstra (1976) found that highly lignified<br />

species had lower in vitro dry matter digestibility<br />

values. Protein content of prairie sandreed decreased<br />

with maturity of the plant. Aase and Wight (1973)<br />

proved that water infiltration rates on undisturbed<br />

prairie sandreed were significantly higher and<br />

averaged about four times those on undisturbed<br />

surrounding vegetation. The duo attributed the<br />

greater infiltration rate in prairie sandreed colonies to<br />

the vigorous growth and resultant residue which<br />

intercepts rain drops and reduces the energy with<br />

which the rain impacts and seals the soils surface.<br />

They also discussed the effect of soil texture on<br />

infiltration rates and noted that coarse textured soils<br />

had higher infiltration rates. Total water use during<br />

the growing season was higher by prairie sandreed<br />

than by the surrounding vegetation, however dry<br />

matter production was twice as great. Production data<br />

collected at Pierre, SD reported prairie sandreed

(ND-95) production at 5,912 kg/ha (5,279 lbs/acre) of<br />

forage compared to 6,667 kg/ha (5,953 lbs/acre) for<br />

big bluestem (‘Bison’) at the same location. <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

sandreed responds positively to prescribed spring<br />

burns.<br />

Pests and Potential Problems<br />

Grasshopper infestations can damage seedlings.<br />

Gophers have been known to undercut, smother and<br />

utilize the forage. Leaf rust (Puccinia amphigena<br />

Dietel.) was identified as a potential antiquality factor<br />

in the forage production of prairie sandreed. Mankin<br />

(1969) also identified leaf mold (Hendersonia<br />

calamovilfae Petr.), leaf spot (Septoria calamovilfae<br />

Petr.) and rust as plant pathogens that can affect<br />

prairie sandreed plants. <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed plants with<br />

origins in the Great Plains are increasingly<br />

susceptible to rust when moved eastward.<br />

Environmental Concerns<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed does not pose any known negative<br />

concerns to the environment. It can form dense<br />

colonies on coarse soils where it is well adapted. This<br />

attribute is often looked at as a positive trait for<br />

increasing ground cover which reduces both wind<br />

and water erosion on these sites.<br />

Control<br />

Please contact your local agricultural extension<br />

specialist or county weed specialist to learn what<br />

works best in your area and how to use it safely.<br />

Always read label and safety instructions for each<br />

control method.<br />

Seeds and <strong>Plant</strong> Production<br />

Calamovilfa is a genus native to North America and<br />

contains five individual species (Rogers, 1970).<br />

Calamovilfa closely resembles Calamagrostis and<br />

Ammophila in gross morphological characteristics,<br />

and was placed close to them in the tribe Agrostideae<br />

by Hitchcock (1951). Reeder and Ellingson (1960)<br />

pointed out that Calamovilfa differs from these<br />

genera in several important embryo characteristics,<br />

types of lodicules, leaf anatomy, and chromosome<br />

size and number. Calamovilfa and Sporoblus appear<br />

to be more closely related and have several features<br />

in common, including the peculiar fruit characteristic<br />

of having its pericarp free from the seed coat, thus<br />

not a true caryopsis (Gould and Shaw, 1983). Reeder<br />

and Singh (1967) determined that the basic<br />

chromosome number of x=10 for Calamovilfa. They<br />

reported that the chromosome number for<br />

Calamovilfa longifolia determined from study of the<br />

meiosis in pollen mother cells in anthers revealed that<br />

the chromosome number is 2n=40. The average seed<br />

production at Bridger, Montana has been 183 kg/ha<br />

under irrigation in 91 cm (36 inch) rows. Seed yields<br />

in North Dakota range from 56 to 560 kg/ha (50 to<br />

500 pounds/acre) under irrigation and 56 to 168<br />

kg/ha (50 to 150 pounds/acre) under dry land<br />

conditions. It is recommended that seed production<br />

fields be planted in row widths of 61 to 91<br />

centimeters (2-3 feet). <strong>Prairie</strong> sandreed is difficult to<br />

harvest in large quantities due to late maturity, seed<br />

shattering, lodging, and hairy seed units. Soil<br />

moisture on seed production fields should be kept at<br />

half field capacity up to flowering. No irrigation<br />

water should be applied during flowering and a<br />

minimum amount of irrigation water should follow<br />

flowering. Combining should be carried out during<br />

the hard dough stage of seed development. Seed<br />

processing should begin with a hammer milling and<br />

then re-cleaning in a fanning mill. A good seed<br />

quality is approximately 85 percent purity with a 75<br />

percent germination which produces a 64 percent<br />

Pure Live Seed (PLS). There are approximately<br />

695,960 seeds in a kilogram (2.54 pounds) of seed.<br />

Cultivars, Improved, and Selected <strong>Materials</strong> (and<br />

area of origin)<br />

Contact your local Natural Resources Conservation<br />

Service office for more information. Look in the<br />

phone book under “United States Government.” The<br />

Natural Resources Conservation Service will be<br />

listed under the subheading “Department of<br />

Agriculture.”<br />

‘Goshen’ prairie sandreed was cooperatively named<br />

and released by the Soil Conservation Service <strong>Plant</strong><br />

<strong>Materials</strong> Center, Bridger, Montana and the Montana<br />

and Wyoming Agriculture Experiment Stations in<br />

1976 (Scheetz and Lohmiller, 1978). The original<br />

germplasm was collected near Torrington, Wyoming<br />

in 1959. It was released without selection and tested<br />

under the experimental designations WY-17 and P-<br />

15588.<br />

‘Pronghorn’ prairie sandreed was released by the<br />

USDA-ARS, the Agriculture Research Division of<br />

the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and the USDA-<br />

SCS Manhattan <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Materials</strong> Center, Manhattan,<br />

Kansas in 1988 (Vogel et al., 1996). An assembly of<br />

48 accessions was collected in 1968 from Kansas,<br />

Nebraska, and South Dakota and established in a<br />

space plant nursery at Manhattan, Kansas. The top<br />

ranked accessions from the nursery were provided to<br />

L.C. Newell, ARS agronomist, for further evaluation.<br />

Selections from the nursery were evaluated for vigor,<br />

forage production and rust tolerance. Evaluation trials<br />

comparing Goshen and Pronghorn revealed that<br />

Pronghorn produced stands and forage equivalent to<br />

Goshen, but was significantly superior with respect to<br />

leaf rust resistance.<br />

ND-95 (Bowman) was selected at the USDA-SCS<br />

<strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Materials</strong> Center, Bismarck, ND. ND-95 is an<br />

informal release of materials collected in 1956 from<br />

southwestern North Dakota (Bowman County). Seed<br />

production is average for the species. Forage<br />

production is comparable to Goshen, in the northern

U.S., but ND-95 has demonstrated improved<br />

performance in parts of Canada. Its dense wiry root<br />

mass makes it well adapted for stabilizing sandy<br />

soils.<br />

Koch Germplasm prairie sandreed was released by<br />

USDA-NRCS Rose Lake <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Materials</strong> Center and<br />

the Michigan Association of Conservation Districts<br />

in 2007. Original germplasm was collected from<br />

native stands in costal zones along Lakes Michigan<br />

and Huron and subjected to three cycles of recurrent<br />

phenotypic selection for upright growth habit, seed<br />

production, and general vigor. Koch Germplasm<br />

prairie sandreed’s anticipated uses include wind<br />

erosion control, dune stabilization, and water quality<br />

improvement in costal zones of the Great Lakes<br />

Region and other sandy areas.<br />

References<br />

Aase, J.K. and J.R. Wight. 1973. <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Sandreed</strong><br />

(Calamovilfa longifolia): water infiltration and<br />

use. Journal of Range Management. 26(3): 212-<br />

214.<br />

Burzlaff, D.F. 1971. Seasonal variations of the in<br />

vitro dry-matter digestibility of three sandhill<br />

grasses. Journal of Range Management. 24:60-<br />

63.<br />

Cogswell, C. and L.D. Kamstra. 1976. The stage of<br />

maturity and its effects upon the chemical<br />

composition of four native range species.<br />

Journal of Range Management. 29(6): 460-463.<br />

Craig, D., K. Sedivec, D. Tober, I. Russell, and T.<br />

Faller. 2002. Nutrient composition of selected<br />

warm-season grasses: Preliminary Report.<br />

USDA-NRCS, Bismarck, ND.<br />

Gould, F.W. and R.B. Shaw.1983. Grass Systematics<br />

2 nd Edition. Texas A&M University Press.<br />

College Station, Texas.<br />

Hitchcock, A.S. 1951. Manual of the grasses of the<br />

United States, 2 nd ed. (Revised by Agnes Chase.)<br />

U.S. Dept. Agric. Misc. Publ. 200.<br />

Mankin, C.J. 1969. Diseases of Grasses and Cereals<br />

in South Dakota. Agriculture Experiment Station<br />

Technical Bulletin 35. South Dakota State<br />

University, Brookings, SD.<br />

Maun, M.A. 1981. Seed germination and seedling<br />

establishment of Calamovilfa longifolia on Lake<br />

Huron sand dunes. Canadian Journal of Botany.<br />

59: 460-469.<br />

Maun, M.A. and S. Riach. 1981. Morphology of<br />

caryopses, seedlings, and seedling emergence of<br />

the grass Calamovilfa longifolia from various<br />

depths in sand. Oecologia. 49:137-1Mullahey,<br />

J.J., S.S. Waller, and L.E. Moser. 1991.<br />

Defoliation effects on yield and bud and tiller<br />

numbers of two Sandhills grasses. Journal of<br />

Range Management. 44(3): 241-245.<br />

Reeder, J.R. and M.A. Ellington. 1960. Calamovilfa,<br />

a misplaced genus of Gramineae. Brittonia.<br />

12:71-77.<br />

Reeder, J.R. and N. Singh. 1967 Chromosome<br />

number in Calamovilfa. Bulletin of the Torrey<br />

Botanical Club. 94:199-200.<br />

Rogers, K.E. 1970. A new species of Calamovilfa<br />

(Gramineae) from North America. Rhodora.<br />

72:72-79.<br />

Scheetz, J.G. and R.G. Lohmiller. 1978. Registration<br />

of Goshen <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Sandreed</strong>. Crop Science.<br />

18:693-694.<br />

Vogel, K.P., L.C. Newell, E.T. Jacobson, J.E.<br />

Watkins, P.E. Reece, and D.E. Bauer. 1996.<br />

Registration of Pronghorn <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Sandreed</strong><br />

Grass. Crop Science. 36:1712.<br />

Waller, S.S. and J.K. Lewis. 1979. Occurrence of C3<br />

and C4 photosynthetic pathways in North<br />

American grasses. Journal of Range<br />

Management. 32:12-28.<br />

Prepared By: Wayne Duckwitz and Richard Wynia<br />

Citation<br />

Duckwitz Wayne, and Wynia, Richard USDA-<br />

Natural Resources Conservation Service <strong>Plant</strong><br />

<strong>Materials</strong> Centers, Bismarck, ND 58502, and<br />

Manhattan, KS 66502 with additional information on<br />

Koch prairie sandreed provided by Rose Lake <strong>Plant</strong><br />

<strong>Materials</strong> Center staff East Lansing, MI 48823.<br />

Published May, 2006<br />

Edited: 16Nov2006jsp, 27Nov2006jsp,<br />

30July2007hsom13Apr2011erg<br />

For more information about this and other plants,<br />

please contact your local NRCS field office or<br />

Conservation District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/<br />

and visit the PLANTS Web site at<br />

http://plants.usda.gov/ or the <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Materials</strong> <strong>Program</strong><br />

Web site http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov.<br />

PLANTS is not responsible for the content or<br />

availability of other Web Sites.<br />

USDA IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY PROVIDER AND EMPLOYER