Volume 10(1): Summer 2003 - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

Volume 10(1): Summer 2003 - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

Volume 10(1): Summer 2003 - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Bulletin<br />

of the<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>10</strong> No.1 <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2003</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> seeks to promote the appreciation, conservation and study of<br />

the lichens. <strong>The</strong> interests of the society include the entire western part of the continent, although<br />

the focus is on <strong>California</strong>. Dues categories (in $US per year): Student and fixed income<br />

- $<strong>10</strong>, Regular - $18 ($20 for foreign members), Family - $25, Sponsor and Libraries<br />

- $35, Donor - $50, Benefactor - $<strong>10</strong>0 and Life Membership - $500 (one time) payable to the<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, P.O. Box 472, Fairfax, CA 94930. Members receive the Bulletin and<br />

notices of meetings, field trips, lectures and workshops.<br />

Board Members of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>:<br />

President: Bill Hill, P.O. Box 472, Fairfax, CA 94930,<br />

email: <br />

Vice President: Boyd Poulsen<br />

Secretary: Judy Robertson (acting)<br />

Treasurer: Stephen Buckhout<br />

Editor: Charis Bratt, 1212 Mission Canyon Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93015,<br />

e-mail: <br />

Committees of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>:<br />

Data Base:<br />

Charis Bratt, chairperson<br />

Conservation: Eric Peterson, chairperson<br />

Education/Outreach: Lori Hubbart, chairperson<br />

Poster/Mini Guides: Janet Doell, chairperson<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (ISSN <strong>10</strong>93-9148) is edited by Charis Bratt with<br />

a review committee including Larry St. Clair, Shirley Tucker, William Sanders and Richard<br />

Moe, and is produced by Richard Doell. <strong>The</strong> Bulletin welcomes manuscripts on technical<br />

topics in lichenology relating to western North America and on conservation of the lichens,<br />

as well as news of lichenologists and their activities. <strong>The</strong> best way to submit manuscripts is<br />

by e-mail attachments or on 1.44 Mb diskette or a CD in Word Perfect or Microsoft Word formats.<br />

Submit a file without paragraph formatting. Figures may be submitted as line drawings,<br />

unmounted black and white glossy photos or 35mm negatives or slides (B&W or color).<br />

Contact the Production Editor, Richard Doell, at for e-mail requirements<br />

in submitting illustrations electronically. A review process is followed. Nomenclature<br />

follows Esslinger and Egan’s 7 th Checklist on-line at . <strong>The</strong> editors may substitute abbreviations of author’s<br />

names, as appropriate, from R.K. Brummitt and C.E. Powell, Authors of Plant Names,<br />

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1992. Style follows this issue. Reprints may be ordered and will<br />

be provided at a charge equal to the <strong>Society</strong>’s cost. <strong>The</strong> Bulletin has a World Wide Web site at<br />

and meets at the group website .<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1) of the Bulletin was issued June 15, <strong>2003</strong>.<br />

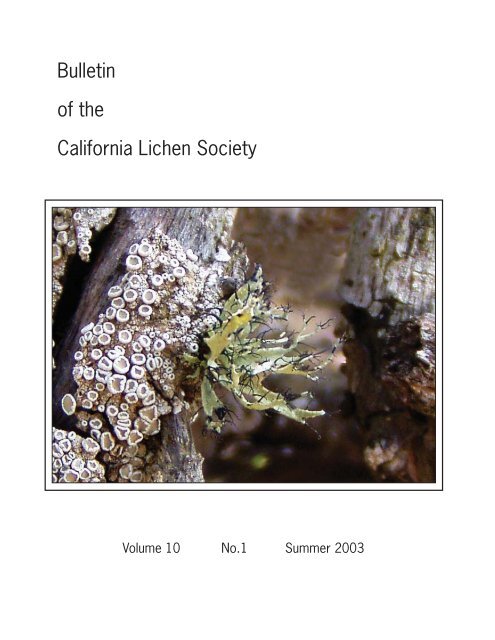

Front cover: Trichoramalina crinata (Tuck.) Rundel & Bowler was photographed by Andrew<br />

Pigniolo with an unidentified crust on a dead branch of Rhus integrefolia on Point Loma in<br />

April <strong>2003</strong>. Ca. 1.5×. (see also Article on p. 9.)

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>10</strong> No.1 <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

<strong>California</strong> and New Zealand: Some <strong>Lichen</strong>ological Comparisons<br />

Darrell Wright<br />

2/150A Karori Rd., Karori<br />

Wellington, New Zealand<br />

dwright3@xtra.co.nz<br />

Abstract: <strong>California</strong> and New Zealand are compared lichenologically with respect to lowland forests and cities.<br />

Usnea wirthii Clerc is reported as new to New Zealand.<br />

<strong>California</strong> lichenologists might wonder if there<br />

is any other place as fascinating for its lichens as<br />

their state, but there are a few areas of the world<br />

to challenge it, and New Zealand looks like a<br />

contender. Although it lacks a true desert such as<br />

the Mojave, it does on the other hand have areas of<br />

very high rainfall, reaching 6985 mm (275 inches)<br />

annually in parts of the South Island (Wards<br />

1976). <strong>California</strong>’s maximum, reached in eastern<br />

Del Norte County, is about 38<strong>10</strong> mm (150 inches:<br />

Spatial Climate Analysis Service 2000). <strong>The</strong> range<br />

of habitats in New Zealand, although wide, would<br />

not be as wide as in <strong>California</strong> with its deserts and<br />

much higher mountains. Table 1 gives some other<br />

numeric com parisons.<br />

90% are gone in <strong>California</strong>; well over half are gone<br />

in New Zealand. <strong>The</strong> great kauri Agathis australis,<br />

(Araucariaceae) and podocarp forests of the North<br />

Island, especially those of totara, Podocarpus totara;<br />

matai, Prumnopitys (Podocarpus) taxifolia, and rimu,<br />

Dacrydium cupressin um (Podocarpaceae, note 1),<br />

were cut and replaced with pasture or with timber<br />

plantations. <strong>The</strong> timber plantations are mostly<br />

of Monterey Pine, Pinus radiata, introduced from<br />

<strong>California</strong> and now the construction timber of New<br />

Zealand. I have looked at several of these ubiquitous<br />

pine plantations, including one quite old one that is<br />

now public open space, and found few lichens in<br />

them. I suspect these plantations, especially the<br />

younger ones (they are harvested at about 30 years)<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong><br />

Genera(1)<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong><br />

Species(1)<br />

Species<br />

richness (2)<br />

Area<br />

km 2 (3)<br />

Latitude (3)<br />

Population<br />

/km 2 (4)<br />

Pop. increase<br />

since 1965 (4)<br />

CA 296 1442 3.6 406,000 33º - 42° N 84 116%<br />

NZ 308 1378 5.1 269,000 34º - 47° S 14 (!) 60%<br />

Table 1. Some comparisons between <strong>California</strong> and New Zealand<br />

Man’s impact on the vegetation of both <strong>California</strong><br />

and New Zealand has been severe. Two pairs of<br />

maps in New Zealand Atlas (Wards 1976, p.<strong>10</strong>4-<strong>10</strong>7),<br />

comparing the vegetation of New Zealand in 1840<br />

with that in 1970, remind me of a map of the North<br />

Coast of <strong>California</strong> on display at the Humboldt<br />

Watershed Council in Eureka, comparing old<br />

growth forests in about 1950 with those of 1990:<br />

do not contribute much to New Zealand lichen<br />

habitat, although more of them, especially in rural<br />

areas, should be examined. <strong>The</strong> pristine lichen<br />

situation in New Zealand must have suffered<br />

badly then with the removal of these forests of<br />

phoro phytes, much as it has suffered in <strong>California</strong>,<br />

and in some areas there would have been a change<br />

towards a drier climate influencing even saxicolous<br />

1

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

communities. New Zealand, however, might be<br />

expected to be overall a better environment for<br />

lichens than <strong>California</strong> in view of its low human<br />

population density (Table 1) and correspondingly<br />

low atmospheric pollution, including acid rain, and<br />

the species richness numbers in Table 1 suggest that<br />

it is a better environment.<br />

Lowland Rainforest<br />

About 40 km north and east of Wellington, the<br />

capital city, is the southern end of the Tararua<br />

Range, part of a 190 km long spine in the lower<br />

third of the North Island with peaks reaching 1570<br />

m (5150 ft.). It is comparable to the Coast Ranges of<br />

<strong>California</strong>, separating the west coast which fronts<br />

on the Tasman Sea, that part of the Pacific Ocean<br />

separating New Zealand from Australia, from the<br />

Wairarapa Valley, comparable on a small scale to the<br />

Central Valley of <strong>California</strong> (although its climate is<br />

more like that of the Napa Valley). This part of<br />

the Tararuas is temperate lowland mixed beech<br />

(Nothofag us, Fagaceae) rain forest and looks more<br />

like coastal Washington State than <strong>California</strong> with<br />

tree trunks and the ground covered by bryo phytes<br />

and lichens (contrary to a theory advanced<br />

once on the Honolulu listserver that, when the<br />

mosses become luxuriant, the lichens recede). <strong>The</strong><br />

appearance is something like the wet coastal forests<br />

of <strong>California</strong> dominated by Pseudotsuga and Sequoia.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are, of course, almost no vascular species in<br />

common. Nothofag us menziesii, the silver beech<br />

(the closest thing New Zealand has to a native<br />

oak) along with N. fusca and perhaps N. solandri<br />

is plentiful in this forest bordering the Waingawa<br />

River. I found other hardwood tree species as well,<br />

like kamahi, Weinmann ia racemosa (Cunoniaceae),<br />

and Five-finger, Pseudopan ax arboreus (Araliaceae),<br />

and a dense understory of shrubs like Coprosma<br />

(Rubiace ae), some of which are garden subjects in<br />

<strong>California</strong>.<br />

At the Mt. Holdsworth entrance to Tararua Forest<br />

Park west of Masterton, Pseudocyphellaria and Sticta<br />

take the place of the Parmeliaceae in <strong>California</strong>, with<br />

huge thalli hanging from tree branches and wet,<br />

bright green, muscicolous-terricolous individuals<br />

growing like lettuce along the trail (more than a<br />

third of Pseudocyphellar ia species here have green<br />

algal photobionts). I have not seen a statistical<br />

survey of this situation, but as early as 1865 the<br />

Scottish lichenologist, W. Lauder-Lindsay (quoted<br />

by Galloway 1985), noted a similar replacement<br />

on the South Island. Although <strong>California</strong> has its<br />

Pseudocyphellar ia species, three to be exact with a<br />

fourth, P. rainierensis, hoped for in Del Norte County,<br />

New Zealand has 50 Pseudocyphellari as according<br />

to Malcolm and Galloway (1997). Galloway (1985)<br />

notes that New Zealand and southern South<br />

America are the two great centers of speciation<br />

for this genus. One of the most remarkable species<br />

is P. coronata (figs. 1 and 2, back cover) in which<br />

red-brown pigment can be seen with the naked<br />

eye in natural cracks in the upper cortex. I did not<br />

observe it in pseudocyphellae of the lower cortex.<br />

A tangential removal of cortex (Hale 1979, p. 11)<br />

shows scattered red-brown areas at the interface<br />

between algal layer (green) and the yellow medulla.<br />

At 400x these are seen to be aggregations of fine,<br />

K+ purple, probably crystalline granules. Polyporic<br />

acid and unidentified anthraquin ones have been<br />

reported (C. Culberson 1969, 1970; C. Culberson et<br />

al. 1977) along with an array of 9 triterpen oids and<br />

3 pulvinic acid-related substances. In connection<br />

with the use of this lichen to produce fabric dyes<br />

Galloway (1985) notes: “Very often populations are<br />

devastated by collectors who imagine that because<br />

the lichen is usually well-developed and also often<br />

common, it must regenerate quickly. In the interests<br />

of conserving New Zealand’s unique lichen flora the<br />

use of lichens for dyeing must be strongly condemned”<br />

(italics mine). <strong>The</strong>re are simply not enough lichens<br />

left in New Zealand or in <strong>California</strong> to be harvesting<br />

them on the scale required for making dyes.<br />

Another Pseudocyphellaria with a quite different,<br />

dissected appearance is P. episticta (fig. 3, back<br />

cover). It occurs inside the forest with Sticta (S.<br />

subcaperata, fig. 4, back cover) and is characteristic<br />

of partially shaded situations. I found it also in the<br />

Johnston Hill Reserve not far from my home in the<br />

city of Wellington. <strong>The</strong>re are 13 species of Sticta<br />

in New Zealand (perhaps three in <strong>California</strong>) of<br />

which the evidently fairly common S. subcaperata<br />

is representative. <strong>The</strong> thallus photographed had<br />

fallen from a tree on the Waingawa River.<br />

Usneas, of which Galloway (1985) lists 16 for New<br />

Zealand (Tavares [1997] gives 24 for <strong>California</strong> in<br />

her preliminary key), are on trees and shrubs in<br />

well-lit places in the rainforest, including several<br />

“reds”, all subsumed by Galloway under U.<br />

2

<strong>Lichen</strong> Comparisons <strong>California</strong>/New Zealand<br />

rubicunda, although he notes the chemistry with<br />

salazinic and norstictic acids does not conform to<br />

the stictic acid chemistry of the type. In fact, some<br />

of these look like the candy-striped material with<br />

norstic tic and salazinic acids (confirmed by TLC,<br />

K+ bright red) which turned up a few years ago<br />

at Pt. Reyes, Marin County, <strong>California</strong> and which<br />

is similar morphologically and chemically to U.<br />

rubescens Stirton. Other specimens have other<br />

distributions of the orangish cortical pigment.<br />

Down in the forest where light levels are low,<br />

Usnea does not occur much, but individuals fallen<br />

from high up will be found lying on the forest<br />

floor (equally the case, for example, in redwood-<br />

Douglas fir forest at Prairie Creek Redwoods<br />

State Park, Humboldt Co., <strong>California</strong>). Handsome,<br />

very fertile U. xanthopha na turned up in this way.<br />

It has fumarprotocetrar ic acid (Galloway 1985)<br />

with a PD+ bright orange-red reaction in the inner<br />

medulla and an interesting PD+ bright yellow<br />

reaction just beneath the cortex (my observation),<br />

perhaps representing a second lichen product<br />

and the one responsible for the K+ brownish<br />

reaction which becomes reddish after a minute. I<br />

wondered how close it might be to U. rigida of the<br />

Pacific Northwest (Halonen et al. 1998), since the<br />

surface morphologies are similar. <strong>The</strong> CMA’s differ<br />

considerably, however: 7:26:33 for Wright 7428, 9:<br />

30:22 for U. rigida from data of Motyka (1936-1938),<br />

who synonymized U. xanthopha na under the New<br />

Zealand endemic U. xanthopoga, a quite different<br />

lichen according to Galloway’s account.<br />

Usnea wirthii Clerc, known in the Western Hemisphere<br />

from Chile and Peru (Clerc 1997) as well as<br />

from <strong>California</strong> and the Mediterranean region, is<br />

also present in New Zealand. I have 2 collections of<br />

this taxon, not yet chromatograph ed, Wright 7340<br />

(medulla K-, PD-; soralia K-, PD+ golden yellow:<br />

presumably the psorom ic acid chemotype), from<br />

Mt. Lees Reserve near Palmers ton North which<br />

agrees well with <strong>California</strong> material except for<br />

the lack of red spots, a condition which may be<br />

the norm for continental Europe (Clerc 1984) and<br />

which is encountered in <strong>California</strong> although rarely<br />

(Wright unpubl.). <strong>The</strong> second collection, this time<br />

with red spots, is Wright 7467 (medulla K+ yellow<br />

becoming quickly deep orange red, PD+ light<br />

orange; what may be incipient soralia are K- and<br />

PD-: presumably the norstict ic acid chemotype<br />

[Wright 2001, Tavares et al. 1998, p. 196]) from<br />

coastal brush on the flank of Makara Hill (400 m<br />

alt.) west of Wellington, establishing the known<br />

range in New Zealand as the Manawatu District<br />

(Palmers ton North) 120 km south to Wellington.<br />

This is the first report of U. wirthii for New Zealand<br />

(W. Malcolm, pers. comm.).<br />

Urban <strong>Lichen</strong>s<br />

All cities I have seen have a few lichens. <strong>The</strong><br />

operative word is “few”: cover is typically low<br />

to very low and the assemblages are species<br />

poor. Berkeley, <strong>California</strong>, for example, has<br />

crustose species on the curb at the incredibly busy<br />

intersection of Ashby and Telegraph Avenues, and<br />

even Red Bluff, set in the center of a lichenological<br />

wasteland in the now chronically desiccated<br />

northern Central Valley, has significant Xanthor ia<br />

on street trees. Wellington, the capital city of New<br />

Zealand with a population of 350,000 at the south<br />

end of the North Island, is rather different in<br />

this respect. <strong>The</strong>re is plentiful Xanthoria parietina<br />

around town, and it is not hard to find other lichens<br />

like the weedy Stereocaulon ramulosum in a garden<br />

in the Kelburn district about 3 km from the city<br />

center (fig. 7). In the same garden was Baeomyces<br />

heterophyl lus and four Cladonia species: C. fimbriata,<br />

Fig. 7. Stereocaulon ramulosum,<br />

Wright 7436. 0.5×.<br />

another member of the C. chlorophaea complex, C.<br />

ochrochlo ra (syn. C. coniocraea), and C. subulata with<br />

an unusual twisting growth habit (fig. 8). All four<br />

species are known also from <strong>California</strong>. Across<br />

3

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

in the city and is considered by Galloway to be<br />

probably a non-native species “whose range has<br />

been greatly increased by man and his activities.”<br />

At the edge of the city Pseudocyphellar ia cf. crocata<br />

does well on the pavement with Xanthoparmel ia<br />

scabrosa. <strong>The</strong>re is even a common urban Usnea, the<br />

“intensely polymorphic” U. arida, which appears to<br />

belong to the U. fragilescens aggregate (Clerc 1987,<br />

p. 487 ff.). It reaches about <strong>10</strong> cm on trees in gardens<br />

here.<br />

Far and away the most remarkable urban<br />

lichen, however, is Xanthoparmelia scabrosa. I am<br />

reproducing here my posting on this species to the<br />

Honolulu lichen listserver in an edited version:<br />

Fig. 8. Cladon ia subula ta,<br />

Wright 7434. 0.6×.<br />

the street on the tile roof of St. Michael’s Church,<br />

Cladia cf. schizophora (fig. 9 and note 2) mingles with<br />

Xanthoparmel ia scabrosa. Downtown along a freeway<br />

exit Xanthoparmel ia mexicana, a species, indeed a<br />

genus, which <strong>California</strong>ns know only from rock,<br />

does well on a wooden fence rail; it is reported also<br />

from bark by Galloway (1985). Parmotre ma chinense,<br />

which I associate with comparatively clean coastal<br />

environments in <strong>California</strong>, is frequent on plantings<br />

Fig. 9. Clad ia cf. schizopho ra,<br />

Wright 7401. 9×<br />

Xanthoparmelia scabrosa is a finely isidiate species<br />

with a very interesting and complex secondary<br />

product chemistry (scabrosins, sulfur and nitrogen<br />

containing compounds with potent activity against<br />

human breast cancer [Ernst-Russell et al. 1999])<br />

known from Argentina, Australia, Japan, New<br />

Guinea, and New Zealand. In New Zealand it has,<br />

at least by the standards of western North America,<br />

a remarkable distribution, on which Mason Hale<br />

commented in his monograph of the genus (Hale,<br />

1990): “It is especially common in New Zealand<br />

where it even grows on pavement and sidewalks<br />

in cities.” A stronger statement could be made: it<br />

is nearly ubiquitous and frequently abundant and<br />

luxuriant, as in the city of Wellington on sidewalks,<br />

asphalt, stone walls, and rocks (figs. 5 and 6,<br />

back cover). I have seen it on glass of a window<br />

in the Kelburn district. It is downtown where it<br />

grows in some cases even where automobiles are<br />

rolling and pedestrians are treading continually.<br />

I am not aware of any equivalent phenomenon<br />

in <strong>California</strong>. T. Ahti (pers. comm., 2002) reports<br />

that there is some Xanthoparmel ia on pavement in<br />

Australia, and M. McCanna in Virginia noted by e-<br />

mail that a Xanthoparmel ia does occur on pavement<br />

of the Blue Ridge Parkway there but not as<br />

luxuriantly as shown in figures 5 and 6 on the back<br />

cover of this issue of the Bulletin. Macrolich ens<br />

(Xanthoparmel ia, Flavoparmelia, even Heteroderm ia)<br />

may rarely be found on pavement in central and<br />

northern <strong>California</strong> on unused streets in housing<br />

developments which were abandoned before the<br />

homes were built and on other little used byways;<br />

X. scabrosa, however, is ex tremely common on<br />

streets and sidewalks, including busy ones.<br />

4

Some of this must have to do with the frequent<br />

light rainfall and comparatively unpolluted air<br />

of a city scoured fairly clean by winds from the<br />

Antarctic and elsewhere, and the use of catalytic<br />

converters to reduce motor vehicle emissions,<br />

but it would seem there must be<br />

something about this lichen as well<br />

that enables it to perform as it does.<br />

Does Xanthoparmel ia scabro sa convert<br />

SO 2<br />

and NO (x)<br />

products into scabrosi n,<br />

rendering those pollutants harmless<br />

<strong>The</strong> fine isidia, which could be<br />

transported by rain wash and to some<br />

extent on the feet of pedestrians, even<br />

on automobile tires, appear to be<br />

high ly effective propagule s.<strong>The</strong> damp<br />

climate with plentiful rain and fog<br />

must contribute also. I have observed<br />

X. scabrosa to be superabundant and<br />

luxuriant on high cliffs that receive<br />

much fog from the Cook Straits,<br />

which separate the North and South<br />

Islands, and on particularly mesic,<br />

protected sidewalks that still get a<br />

fair amou nt of sun. James Bennett<br />

of the University of Wisconsin and<br />

I will soon publish a survey and<br />

interpretation of the elemental<br />

content of X. scabrosa from clean and<br />

from polluted areas in New Zealand.<br />

Names of the New Zealand taxa<br />

follow Galloway (1985) for lichens and Metcalf<br />

(2002) for vascular plants. Names of the <strong>California</strong><br />

taxa follow Esslinger (1997) for lichens and<br />

Hickman (1993) for vascular plants.<br />

Notes:<br />

1. Podocarpaceae, unfamiliar to most Americans,<br />

reach the Northern Hemisphere only in Asia. <strong>The</strong><br />

native taxa closest to them are the Taxaceae: the<br />

Western Yew, Taxus brevifolia, and the <strong>California</strong><br />

Nutmeg, Torreya californica, both uncommon to rare.<br />

Podocarpaceae and Taxaceae are gymnosperms<br />

which produce seeds not in cones but singly atop<br />

brightly colored receptacles.<br />

2. Cladia, a southern hemisphere genus is known to<br />

North Americans chiefly, I suspect, from photos of C.<br />

retipora (see, e.g., Nash [1996], p.44, fig.9), an unusual<br />

species comparable for its strong fenestration to<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong> Comparisons: Califronia/New Zealand<br />

Ramalina menziesii, although it is much smaller and<br />

less conspicuous. Cladia is much like Cladina but with<br />

a cortex, often with tiny perforations (except in C.<br />

retipora which has very large perforations compared<br />

with other Cladia species). In fig. 9 see below and to<br />

Fig. <strong>10</strong>. A magnificent tree, probably Silver Beech, Nothofag us menzies ii,<br />

photographed on the bank of the Wainga wa River near the Pseudocyphellar ia and<br />

Sticta collecting sites. Note the abundant epiphytes, many of which are lichens<br />

(the large epiphyte in the center is a monocot flowering plant).<br />

the right of center.<br />

Notes for Table 1:<br />

1. <strong>California</strong>: S. Tucker, pers. comm., 11-2002; New<br />

Zealand: Malcolm and Galloway 1997.<br />

2. Species richness for purposes of this discussion =<br />

total spp. ÷ area x <strong>10</strong>00 (species per square km x <strong>10</strong>00),<br />

using values from references 1 and 3.<br />

3. Hammond Universal World Atlas, C.S. Hammond<br />

Co., New Jersey, 1965.<br />

4. Based on a population for <strong>California</strong> of 34 million<br />

(http://www.ca.gov/state/portal/myca_homepage.<br />

jsp, <strong>California</strong> Facts, <strong>California</strong> Demographics,<br />

accessed 11-7-02), and for New Zealand of 3.9 million<br />

(http://www. stats.govt.nz, Top 20 Statistics, accessed<br />

11-7-02).<br />

5

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

References Cited<br />

Clerc, P. 1984. Usnea wirthii – A new species of<br />

lichen from Europe and North Africa. Saussurea<br />

15: 33-36.<br />

Clerc, P. 1987. Systematics of the Usnea fragilescens<br />

aggregate and its distribution in Scandinavia.<br />

Nordic Journal of Botany 7: 479-495.<br />

Clerc, P. 1997. Notes on the genus Usnea Dill. ex<br />

Adanson. <strong>Lichen</strong>ologist 29(3): 209-215.<br />

Culberson, C. 1969. Chemical and Botanical Guide<br />

to <strong>Lichen</strong> Products. University of North Carolina<br />

Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.<br />

Culberson, C. 1970. Supplement to “Chemical<br />

and Botanical Guide to <strong>Lichen</strong> Products.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> American Bryological and <strong>Lichen</strong>ological<br />

<strong>Society</strong>, St. Louis, Missouri.<br />

Culberson, C., W. Culberson, and A. Johnson. 1977.<br />

Second Supplement to “Chemical and Botanical<br />

Guide to <strong>Lichen</strong> Products.” <strong>The</strong> American<br />

Bryological and <strong>Lichen</strong>ological <strong>Society</strong>, St.<br />

Louis, Missouri.<br />

Ernst-Russell, M.A., C. Chai, A. Hurne, P. Waring,<br />

D. Hockless, and J. Elix. 1999. Structure revision<br />

and cytotox ic activity of the scabrosin esters,<br />

epidithiopiperazinedi ones from the lichen<br />

Xanthoparmel ia scabrosa. Australian Journal of<br />

Chemistry 52: 279-283<br />

.<br />

Esslinger, T. L. 1997. A cumulative checklist for the<br />

li chen-forming, lichenicolous and allied fungi<br />

of the continental United States and Canada.<br />

ndsu.nodak.edu/instruct/esslinge/1997,<br />

most recent update July 17, 2002, Fargo, North<br />

Dakota.<br />

Galloway, D.J. 1985. Flora of New Zealand.<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s. P.D. Hasselberg, Government Printer,<br />

Wellington, New Zealand.<br />

Hale, M.E. 1979. How to Know the <strong>Lichen</strong>s.<br />

William Brown Co., Dubuque, Iowa.<br />

Hale, M.E. 1990. A synopsis of the lichen genus<br />

Xanthoparmel ia (Vainio) Hale (Ascomycotina,<br />

Parmeliaceae). Smithsonian Contributions to<br />

Botany 74: 189.<br />

Halonen, P., P. Clerc, T. Goward, I.M. Brodo, and<br />

K. Wolff. 1998. Synopsis of the genus Usnea<br />

(<strong>Lichen</strong>ized Ascomy cetes) in British Columbia,<br />

Canada. <strong>The</strong> Bryologist <strong>10</strong>1(1): 36-60.<br />

Hickman, J., ed. 1993. <strong>The</strong> Jepson Manual. Higher<br />

Plants of <strong>California</strong>. U.C. Press, Berkeley,<br />

<strong>California</strong>.<br />

Metcalf, L. 2002. Trees of New Zealand. New<br />

Holland Publishers, Auckland, New Zealand.<br />

Motyka, J. 1936-1938. <strong>Lichen</strong>um Generis Usnea<br />

Studium Monographicum. Pars Systematica.<br />

Published by the author, Leopoli.<br />

Nash, T.H. III, ed. 1996. <strong>Lichen</strong> Biology. Press<br />

Syndicate of the University of Cambridge,<br />

Cambridge, England.<br />

Spatial Climate Analysis Service, Oregon State<br />

Uni versity. 2000. Average Annual Precipitation,<br />

<strong>California</strong> (map of precipitation averaged over<br />

the period 1961-1990). On-line at http://<br />

www.ocs.orst.edu/pub/Precipita tion/Total/<br />

States/CA/ca.gif, accessed November 11, 2002.<br />

Tavares, I. 1997. A preliminary key to Usnea in<br />

<strong>California</strong>. Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> 4(2): 19-23.<br />

Tavares, I., D. Baltzo, and D. Wright. 1998. Usnea<br />

wirthii in western North America, pp. 187-<br />

199. In M. Glenn et al. (Eds.), <strong>Lichen</strong>ographia<br />

Thomsonia na: North American <strong>Lichen</strong>ology in<br />

Honor of John W. Thomson, Mycotax on Ltd.,<br />

Ithaca, New York.<br />

Wards, I., ed. 1976. New Zealand Atlas. A.R.<br />

Shearer, Gov ernment Printe r, Wellington, New<br />

Zealand.<br />

Wright, D. 2001. Some species of the genus Usnea<br />

(licheniz ed ascomy cetes) in <strong>California</strong>. Bulletin<br />

of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 8(1): 1-21.<br />

6

Pacific Northwest <strong>Lichen</strong>s in Northern <strong>California</strong><br />

Tom Carlberg<br />

Six Rivers National Forest<br />

Eureka, CA 95501<br />

tcarlberg@fs.fed.us<br />

Northern <strong>California</strong> and southern Oregon share<br />

many attributes of climate and geography, with<br />

the result that the lichen flora of these two political<br />

entities is similar. Common to both states are<br />

the coastal environs of the Pacific Ocean, the<br />

Klamath, Siskiyou and Cascade Mountains, the<br />

Coast Ranges, the Illinois and Klamath Rivers,<br />

and large fast-growing conifer forests that include<br />

both ubiquitous commercially valuable species and<br />

scarce remnant species. A number of lichen species<br />

approach the southern extent of their ranges here,<br />

becoming rare or confined to specific habitats,<br />

including Usnea longissima, Platismatia lacunosa,<br />

Ramalina thrausta, Nephroma bellum and others.<br />

<strong>The</strong> coastal influence that extends strongly to the<br />

Cascade Mountains in Oregon does not penetrate<br />

as far inland in <strong>California</strong>, with the result that lichen<br />

species widely distributed in western Oregon are<br />

confined to more coastal areas in <strong>California</strong>.<br />

As a result of an ongoing correspondence with<br />

Dr. Shirley Tucker at the University of <strong>California</strong>,<br />

Santa Barbara, there is new information available<br />

regarding the occurrence of some lichens in<br />

northern <strong>California</strong> that are considered to be<br />

infrequent to common in the Pacific Northwest but<br />

are apparently either unreported from <strong>California</strong><br />

in the literature or reported only in secondary<br />

sources (keys or general texts). <strong>The</strong>se omissions<br />

came to light as a result of Dr. Tucker’s review of<br />

a species list from the Six Rivers National Forest<br />

cryptogamic herbarium, and her review of selected<br />

specimens towards the eventual revision of A<br />

Catalog of <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong>s (Tucker & Jordan 1979).<br />

Some of the lichens discussed are new reports for<br />

<strong>California</strong>, although given that none are truly rare<br />

in the Northwest, their absence from the published<br />

literature is probably more a matter of omission,<br />

undercollecting, and the limited number of lichen<br />

surveys that have taken place in the area.<br />

Alectoria lata (Taylor) Lindsay – Primary citation in<br />

Brodo & Hawksworth (1977); secondary citations<br />

in Brodo et al. (2001) and Tucker & Jordan (1979).<br />

Brodo & Hawksworth (1977) cite a Weber collection<br />

(Weber Lich. Exs. 417) from the summit of Horse<br />

Mountain. Recent collections of A. lata have been<br />

made by Darrell Wright and Doug Glavich (Wright,<br />

pers. comm., Glavich, pers. comm.) in what is<br />

now the Horse Mountain Botanical Area in Six<br />

Rivers National Forest. It is also known from Elk<br />

Valley Ridge in Six Rivers National Forest (Hoover<br />

LDH01). <strong>The</strong> Northwest <strong>Lichen</strong> guild considers<br />

it uncommon enough to include it in their Listed<br />

Macrolichens in the Pacific Northwest (<strong>2003</strong>).<br />

Cornicularia normoerica (Gunn.) Du Rietz – Primary<br />

citation in Sigal & Toren (1974); secondary citations<br />

in Brodo et al. (2001) and Tucker & Jordan (1979).<br />

This lichen might be underreported because<br />

of its affinity for exposed rocky alpine and<br />

subalpine habitats, although as with Alectoria lata<br />

it is included in Listed Macrolichens in the Pacific<br />

Northwest. Collected from the summit of Broken<br />

Rib Mountain in the Broken Rib Botanical Area in<br />

Six Rivers NF (Carlberg 00633).<br />

Icmadophila ericitorum (L.) Zahlbr. – Common on<br />

conifers in the older redwood forests, this lichen<br />

has one primary citation in Tucker & Kowalski<br />

(1975) and secondary citations in Brodo et al. (2001),<br />

Jørgensen & Goward (1994), and Tucker & Jordan<br />

(1979). <strong>The</strong> common name is “fairy puke”. It is<br />

distributed across most of Canada but is largely<br />

absent from North America, except for a few areas<br />

of incursion, extending no further south than<br />

Northern <strong>California</strong> on the Pacific coast (Brodo et<br />

al. 2001). <strong>The</strong> Six Rivers collection (Isaacs/McFarland<br />

23) is from the southern part of the forest.<br />

Leptogium polycarpum P.M. Jørg. & Goward – No<br />

primary citations; secondary citation in Brodo et al.<br />

(2001). Goward et al. (1994) list this lichen as rare in<br />

British Columbia; McCune & Geiser (1997) describe<br />

it as one of the most common Leptogium species in<br />

western Oregon. <strong>The</strong> two reported locations in<br />

<strong>California</strong> are both associated with riparian areas.<br />

In Six Rivers NF (Carlberg 00612) it was found in the<br />

headwaters of the Little Van Duzen River. <strong>The</strong> other<br />

location is in the Mattole River valley (Carlberg<br />

7

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

00658). It is only recently described (Jorgensen &<br />

Goward 1994) and may appear in collections under<br />

other names.<br />

Leptogium subaridum Jørgensen & Goward – No<br />

primary or secondary citations. This appears to<br />

be a first report for <strong>California</strong>, although as with<br />

L. polycarpum it was newly described in 1994<br />

(Jorgensen & Goward [1994]). Two collections, both<br />

from riparian areas in Six Rivers NF (Carlberg 00560<br />

and 00600).<br />

Parmelia pseudosulcata Gyelnik – No primary<br />

citations; two secondary citations in Goward et al.<br />

(1994) and Hale & Cole (1988). In Six Rivers NF<br />

(Isaacs/Bergman 42).<br />

Peltigera neckeri Hepp ex Müll. Arg – No primary<br />

or secondary citations. One collection from Six<br />

Rivers (Isaacs/Bergman 51) from a densely-forested<br />

north slope, and another from private land near the<br />

coast (Carlberg 00436), in an oak pocket in a tanoak-<br />

Douglas-fir forest.<br />

Peltigera neopolydactyla (Gyelnik) Gyelnik – No<br />

primary citations; one secondary citation in Brodo<br />

et al. 2001. Occurs with some frequency in moist<br />

coastal forests on the immediate coast near the town<br />

of Orick (Carlberg 00056, 00801) and on the Samoa<br />

Peninsula near Arcata (Glavich, pers. comm.).<br />

Peltigera ponojensis Gyelnik – No primary citations;<br />

three secondary citations in Brodo et al. 2001,<br />

Goward et al. (1994) and McCune & Geiser (1997).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Six Rivers occurrence is on the immediate<br />

coast, but another location on Grizzly Creek on<br />

the Shasta-Trinity National Forest (Carlberg 00748)<br />

demonstrates that this species has the potential for<br />

a broader range in northern <strong>California</strong>.<br />

Psoroma hypnorum (Vahl) Gray – No primary<br />

citations; one secondary citation in Hale (1979).<br />

Dr. Tucker included a request in the <strong>CALS</strong> Bulletin<br />

(Winter 2002) for information on <strong>California</strong><br />

collections of this species. It is not mentioned in<br />

Hale & Cole (1988). <strong>The</strong> three locations in Six Rivers<br />

NF are very different, one being a moist location<br />

at the top of Mill Creek where it is abundant in<br />

mosses on rocks and soil. <strong>The</strong> other two are both<br />

in the Broken Rib Botanical Area, but occur there<br />

sparsely and are restricted to the bases of trees.<br />

I would be interested to hear from others who have<br />

collections of any of these species, since there is a<br />

strong possibility that these lichens are not really<br />

unusual for <strong>California</strong>. If so it argues strongly for<br />

an accessible database of <strong>California</strong> lichens that<br />

reports at least the verified presence of taxa in the<br />

state, and at best includes information regarding<br />

abundance and location, and the likelihood of new<br />

species based on their presence in adjacent areas.<br />

Brodo, I.M., S. Duran Sharnoff, S. Sharnoff. 2001,<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s of North America. Yale University<br />

Press, New Haven CT.<br />

Brodo, I.M. & D.L. Hawksworth. 1977. Alectoria and<br />

allied genera in North America. Opera Botanica<br />

42:1-164.<br />

Glavich, D. 2001. Personal communication. USDA<br />

Forest Service.<br />

Goward, T., B. McCune, D. Meidinger. 1994. <strong>The</strong><br />

lichens of British Columbia, part 1 – foliose<br />

and squamulose species. Research Program,<br />

Ministry of Forests, Victoria, BC.<br />

Hale, M.E., Jr. 1979. How to know the lichens. 2nd<br />

Edition. Wm. C. Brown Co., Dubuque, Iowa.<br />

Hale, M.E. & M. Cole. 1988. <strong>Lichen</strong>s of <strong>California</strong>.<br />

University of <strong>California</strong> Press, Berkeley.<br />

Jørgensen, P.M. & T. Goward. 1994. Two new<br />

Leptogium species from western North America.<br />

Acta Botanica Fennica 150:75-78.<br />

McCune, B. & L. Geiser. 1997. Macrolichens of<br />

the pacific northwest. Oregon State University<br />

Press, Corvallis, OR.<br />

Northwest <strong>Lichen</strong> Guild. <strong>2003</strong>. Listed<br />

macrolichens in the Pacific Northwest. http:<br />

//www.proaxis.com/~mccune/listed.htm.<br />

Accessed April <strong>2003</strong>.<br />

Sigal, L.L. & D. Toren. 1974. New distribution of<br />

lichens in <strong>California</strong>. <strong>The</strong> Bryologist 77: 469-<br />

470.<br />

Tucker, S.C. & D.T. Kowalski. 1975. New state<br />

records of lichens from northern <strong>California</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bryologist 78:366-368.<br />

Tucker, S.C. & W.P. Jordan. 1979. A catalog of<br />

<strong>California</strong> lichens. Wassmann Journal of<br />

Biology 36:1-<strong>10</strong>5.<br />

Wright, D. 2001. Personal communication.<br />

<strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

8

An Exciting Find<br />

Charis C. Bratt<br />

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden<br />

1212 Mission Canyon Road<br />

Santa Barbara, CA 93<strong>10</strong>4<br />

cbratt@sbbg.org<br />

Years ago when I first started studying lichens,<br />

I was inspired by specimens at the Smithsonian<br />

Institution which were collected in the late 1800s<br />

and the early 1900s. Hasse’s book of southern<br />

<strong>California</strong> lichens listed many species and their<br />

distributions. Small wonder that I was led to start<br />

searching for those that I had seen or read about.<br />

Teloschistes californica, or T. villosus as it was known<br />

then, was represented at the Smithsonian by lovely<br />

specimens and was described in Hasse from Lower<br />

<strong>California</strong> (Baja), Point Loma near San Diego, near<br />

Newport and as far north as Santa Cruz Island<br />

where it was collected by Blanche Trask. Hasse’s<br />

Exsiccati #134 of this species was collected at San<br />

Quintin Bay in Baja. This may indicate that it was<br />

not plentiful at Point Loma. For over 20 years now,<br />

this species has eluded me on mainland <strong>California</strong>.<br />

In all my explorations of Point Loma and in the<br />

Newport area, it has not been found. I have found it<br />

in Baja and I have collected it on 6 of the 8 Channel<br />

Islands, but not Catalina or Santa Cruz Islands.<br />

It was not included in the Flora of Santa Catalina<br />

Island.<br />

Trichoramalina crinata, or Ramalina crinata as it<br />

was called then, is another species represented in<br />

the Smithsonian collections and in Hasse’s book.<br />

It, too, is found in Baja but only the Point Loma<br />

location was given for <strong>California</strong>. Hasse’s Exsiccati<br />

#115 was collected at Point Loma in 1909 which<br />

would lead us to suppose that it existed there in<br />

quantity.<br />

After the lichen walk at Point Loma in April, I<br />

was shown a different area of Point Loma. While<br />

there, Andrew Pigniolo handed me a tiny specimen<br />

asking what the thing with black cilia was (see<br />

front cover image). I knew immediately that he<br />

had found Trichoramalina! Quite obviously, he<br />

would not have picked it had he know its rarity.<br />

<strong>The</strong> specimen now resides at the Santa Barbara<br />

Botanic Garden as proof that it still exists in <strong>2003</strong>. A<br />

few other small specimens were located in the area.<br />

Andy is now working with people from the City of<br />

San Diego to see if some protection can be given to<br />

the area as there are other rare things known from<br />

this place.<br />

It was a very exciting day for Andy, Kerry Knudsen<br />

and me. It also points out that the more people we<br />

have in the field looking at lichens, the more we<br />

are going to find and learn about. Nothing could<br />

demonstrate this more clearly than last issue’s<br />

article and pictures of Texosporium sancti-jacobi.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re has been an explosion of sitings since then<br />

which will be presented in the December issue.<br />

Happy lichening!<br />

References<br />

Hasse, H.E. 1913. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> Flora of Southern<br />

<strong>California</strong>, Contributions from the United States<br />

National Herbarium, Vol. 17, Part 1.<br />

Millspaugh, C.F., L.W. Nuttall. 1923. Flora of Santa<br />

Catalina Island. Field Museum, Publication 212,<br />

Vol. V, Chicago, IL.<br />

9

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

Clarification of three Umbilicaria species new to <strong>California</strong><br />

Eric Peterson<br />

Nevada Natural Heritage<br />

1550 E. College Pkwy, Suite 145<br />

Carson City, NV 89706<br />

peterson@govmail.state.nv.us<br />

In 1998 I reported Umbilicaria lambii Imshaug and<br />

U. rigida (Du Rietz) Frey as new to <strong>California</strong> in the<br />

Proceedings of the First Conference on Siskiyou<br />

Ecology (Peterson 1998). Unfortunately those<br />

proceedings were informally published, leading to<br />

a difficult-to-find, and potentially invalid, report of<br />

the species. This note is to establish a more tangible<br />

report that the two species occur in <strong>California</strong>.<br />

Further, the only published specimen report of<br />

Umbilicaria phaea var. coccinea Llano in <strong>California</strong><br />

was more than 50 years ago (Llano 1950), so two<br />

locations for that taxon are also reported here.<br />

Umbilicaria lambii and U. rigida were found on the<br />

same ultramafic rock outcrop near Sanger Peak in<br />

Del Norte County, <strong>California</strong>. <strong>The</strong> site was along a<br />

wind (and fog) swept ridge at ca. 1700 m elevation<br />

and within 50 km of the Pacific Coast. <strong>The</strong> original<br />

specimens collected by myself with Martin Hutten<br />

were identifiable but small, so I collected additional<br />

voucher specimens at a later date. U. lambii is<br />

rather unusual for the genus in that it has a nearly<br />

squamulose growth form. Previously U. rigida was<br />

known from Oregon and northward, while U. lambii<br />

was known from Washington and northward.<br />

Umbilicaria phaea var. coccinea is unusual for the<br />

genus in that it has a deep red color. It is commonly<br />

called the “lipstick lichen” because in its habitat, it<br />

looks like someone took a tube of red lipstick and<br />

dotted the rock. <strong>The</strong> taxon was found at 2 locations<br />

near Interstate Highway 5, Siskiyou County. It is<br />

abundant in the area, frequently growing right<br />

along side of var. phaea. U. phaea var. coccinea is a<br />

rather locally distributd taxon, occurring in the<br />

drier, eastern portion of the Klamath region of<br />

northern <strong>California</strong> and southern Oregon, and with<br />

several disjunct populations in eastern Oregon and<br />

eastern Washington.<br />

Specimens<br />

Umbilicaria lambii: EBP #2485 (OSC) and EBP #2539<br />

(hb. Peterson, hb. McCune, OSC); on ultramafic<br />

rock; subalpine rocky outcrops among dense<br />

shrubs and sparse trees (Abies sp., Picea breweriana,<br />

Pinus monticola, Pseudotsuga menziesii); along trail<br />

to Sanger Peak on S side before it crosses ridge;<br />

41°55.2’N, 123°39.2’W; 1700 m elevation; 1 June<br />

1997 (#2485) and 15 August 1997 (#2539).<br />

Umbilicaria phaea var. coccinea: EBP #1527 (hb.<br />

Peterson); on rock; chaparral and oak savanna<br />

on NW facing slope with rocky ground (Quercus<br />

garryana, Ceanothus spp.); 1 km E of Hilt, Jefferson<br />

road, NE side of small rock quarry at end of county<br />

road; 41°59.8’ N, 122°36.5’W; 900-1<strong>10</strong>0 m elevation;<br />

17 May 1996. EBP #2458 (hb. Peterson); on rock,<br />

basalt; chaparral dominated by Ceanothus, lower<br />

slope, S face; along Klamath River upstream from<br />

Shasta River – just SW of intersection of HWY 96<br />

and Interstate 5, along an annual creek just after<br />

HWY 96 curves right when going south from<br />

intersection; 41°50.9’ N, 122°34.4’W; m elevation;<br />

3 May 1997.<br />

Umbilicaria rigida: EBP #2494 (OSC) and EBP #2540<br />

(OSC); on ultramafic rock; subalpine rocky outcrops<br />

among dense shrubs and sparse trees (Abies sp.,<br />

Picea breweriana, Pinus monticola, Pseudotsuga<br />

menziesii); along trail to Sanger Peak on S side<br />

before it crosses ridge; 41°55.2’ N, 123°39.2’W; 1700<br />

m elevation; 1 June 1997 (#2494) and 15 August<br />

1997 (#2540).<br />

Literature Cited<br />

Llano, GA 1950. A Monograph of the <strong>Lichen</strong> Family<br />

Umbilicariaceae in the Western Hemisphere.<br />

Navexos P-831. Office of Naval Research,<br />

Washington, D.C. 281 pp.<br />

Peterson, E. B. 1998. <strong>Lichen</strong>s of the Klamath<br />

Region: what do we know and why haven’t<br />

we found endemics In: J. K. Beigel, E. S. Jules,<br />

and B. Snitkin (eds.), Proceedings of the First<br />

Conference on Siskiyou Ecology. Siskiyou<br />

Regional Education Project and <strong>The</strong> Nature<br />

Conservancy, Portland, Oregon.<br />

<strong>10</strong>

Questions and Answers<br />

Janet Doell<br />

1200 Brickyard Way #302<br />

Point Richmond, CA 94801<br />

rdoell@sbcglobal.net<br />

When talking to the general public about lichens<br />

on field trips or at workshops, I am asked certain<br />

questions which are of common interest to those<br />

attending. Three such questions are answered<br />

below. <strong>The</strong> column is meant to serve people who<br />

are new to lichens and do not have easy access to<br />

lichen literature.<br />

1. Question: How are lichens classified<br />

Answer: This question was addressed in this<br />

column a few years ago. It keeps reappearing,<br />

however. Maybe it is time to take it up again.<br />

Whatever method of classification is used, the<br />

huge input of information becoming available<br />

to lichenologists in the modern world leads to<br />

constant change and rearrangements. Taxa come<br />

and taxa go and sometimes taxa return. <strong>The</strong><br />

advent of scanning electron microscopy was one<br />

new source of information some years ago, soon<br />

followed by the results of ongoing DNA and other<br />

molecular studies.<br />

Classification involves placing individuals in<br />

groups according to their similarities in morphological,<br />

chemical and molecular characteristics. In<br />

some branches of biology cladistics are used – that<br />

is, grouping according to known ancestry. Phenetics<br />

is another method of classification, which is<br />

more numerical and relies on overall percentage<br />

similarities. <strong>Lichen</strong>ologists, on the whole, have<br />

continued to use traditional, evolutionary systematics.<br />

In our newest major lichen text, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong>s<br />

of North America, by Brodo and the Sharnoffs, classification<br />

follows this model.<br />

We start with the kingdom. <strong>Lichen</strong> names all refer<br />

to the fungal partner only, and lichens are thus in<br />

the Kingdom Fungi.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lichen forming fungi are divided into two<br />

Classes (sometimes called Phyla): 1. Basidiomycetes,<br />

of which there are only a few, where the spores are<br />

formed outside the basal cell called a bacidium,<br />

and 2. Ascomycetes, in which the spores are formed<br />

internally in a sac-like ascus. In this class we find<br />

80% of lichens.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n there are two subclasses: 1. Euascomycetes<br />

in which the asci have single layered walls and<br />

the ascocarps (fruiting bodies) have paraphyses<br />

(specialized fungal filaments) in the hymenium<br />

(spore bearing layer). 2. Loculoascomycetes,<br />

without true paraphyses and with double walled<br />

asci.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se subclasses are divided into orders. <strong>The</strong> names<br />

of these orders end in “ales”, i.e., Caliciales, and<br />

these divisions are based on general characteristics<br />

of asci and apothecia and type of photobiont (algal<br />

or cyanobacterial partner). <strong>The</strong> largest order is<br />

that of the Lecanorales, which is divided into suborders.<br />

<strong>The</strong> orders are divided into families, names ending<br />

in “aceae”, i.e., Caliciaceae. <strong>The</strong>se divisions are<br />

based on general morphological characters and<br />

reproductive details .<br />

Within the families you find the genera, i.e.,<br />

Calicium, determined by more details about<br />

chemicals, spore structure and other features. From<br />

11

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

there you go to species. <strong>The</strong> question of exactly<br />

what determines a species in lichenology probably<br />

deserves an answer all its own. Perhaps in the next<br />

Bulletin<br />

2. Question: How do toxic compounds actually<br />

kill a lichen<br />

Answer: Absorption of toxic compounds causes<br />

degradation of the chlorophyl until photosynthesis<br />

is no longer possible and the lichen has no source<br />

of nourishment.<br />

3. Question: What can one do to keep a lichen<br />

alive on a rock or manmade surface<br />

Answer: This question is asked so often that the<br />

British <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> has published a free brochure<br />

on the subject, also including advice on how to get<br />

rid of an unwanted lichen. I quote:<br />

“Over the past few years many different substances<br />

have been painted onto buildings to encourage<br />

more rapid colonization. <strong>The</strong>se include yogurt,<br />

beer, skimmed milk, thin porridge and, in Japan,<br />

rice water. To all these substances a small quantity<br />

of PVA (polyvinyl acetate) adhesive may be added.<br />

This acts as a binder, improves the adhesion of the<br />

nutrient and possibly allows more gradual release<br />

over a longer period. On very alkaline materials,<br />

such as new concrete, a slightly acid substance<br />

will assist in neutralizing the high alkalinity. Dilute<br />

cow slurry is frequently used, the urine present<br />

providing the acid content and the brown staining,<br />

caused by the slurry, giving an immediate toning<br />

down of the concrete. Little work so far has been<br />

done to determine the frequency of application or<br />

strength required. <strong>The</strong> evidence from those who<br />

have tried these methods seems to show that they<br />

work. Various timings have been suggested but it<br />

is probably worth trying about four applications at<br />

yearly intervals. Even a single application would<br />

probably assist, but due to the very alkaline nature<br />

of new concrete it would be more effective to give<br />

at least a second coat after about two years. On<br />

more acid stones, such as granite and sandstone,<br />

it is suggested that, especially in polluted areas,<br />

powdered chalk be added to the mixture to<br />

neutralize this acidity to some extent. To aid<br />

colonization, coarsely ground up pieces of lichen<br />

can be added to the mixture before it is painted<br />

on to the surface. Care should be taken to use only<br />

lichens that are growing abundantly in the local<br />

area, and which are found in a similar microhabitat<br />

to that on which they are placed.”<br />

References<br />

Brodo, I.M., S.D. Sharnoff, and S. Sharnoff. 2001.<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s of North America. Yale University<br />

Press, New Haven.<br />

Dobson, Frank S. 1996. <strong>Lichen</strong>s on Manmade<br />

Surfaces. British <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, London.<br />

Gries, C. 1996. In <strong>Lichen</strong> Biology. Thomas H. Nash<br />

III, Editor. Cambridge University Press, New<br />

York.<br />

12

Literature Reviews and Remarks<br />

Kerry Knudsen<br />

33512 Hidden Hollow Drive<br />

Wildomar, CA 92595<br />

kk999@msn.com<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin by John Thomson<br />

(Wisconsin State herbarium, <strong>2003</strong>) sets the standard<br />

for what a state lichen flora should be. 148 genera<br />

and 615 species are covered including species to<br />

be expected in the area but not yet collected. <strong>The</strong><br />

keys are relatively easy and excellent. <strong>The</strong>y can be<br />

utilized experimentally in <strong>California</strong> to key a crust<br />

to genus or find a Lecidea segregate. <strong>The</strong> descriptions<br />

of species are in the concise minimalist style of<br />

Thomson’s Arctic floras. Like Hasse’s equally short<br />

descriptions, they can contain gems of information<br />

mined from the author’s direct observations of<br />

numerous specimens.<br />

<strong>The</strong> comprehensiveness, the concise descriptions,<br />

and efficient keys of Thomson’s flora should be<br />

the principle characteristics of any good state flora.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se virtues guarantee its value for use by nonlichenologist<br />

professionals, who can utilize it in the<br />

context of ecological and biodiversity studies, land<br />

management and other work, and for the serious<br />

amateur who is ready to graduate from macrolichen<br />

guides. It is hoped that one day we will see Hale’s<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s of <strong>California</strong> surpassed by a state flora<br />

equaling Thomson’s <strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin.<br />

One of the imperatives of lichenology in the<br />

beginning of the 21 st century is to establish a finelydetailed<br />

model of the distribution of lichens in<br />

North America and Mexico. To show how much<br />

work has to still be done in this area, the Preface to<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin gives an illuminating example.<br />

A lichen workshop was held in Wisconsin in April,<br />

2002. After making field collections in northern<br />

Wisconsin, participants in the workshop were given<br />

preview copies of <strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin to key out<br />

their collections. <strong>The</strong> workshop produced 130 new<br />

county records and 47 new state records (which are<br />

included in Appendix 1.) And Wisconsin is not only<br />

a state where Thomson himself collected for years,<br />

but was also collected by his graduate students<br />

Mason E. Hale Jr. and William L. Culberson.<br />

Though the Sonoran Flora will be the ultimate<br />

and magisterial reference for the lichen flora of<br />

Southern <strong>California</strong>, and will be the touchstone<br />

of accurate determinations, only a state flora of<br />

<strong>California</strong> will bring into proper perspective the<br />

unique natural history of cismontane Southern<br />

<strong>California</strong> and its relation to Northern <strong>California</strong>’s<br />

lichen flora. <strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin does that service<br />

for its state. Wisconsin is divided into two natural<br />

provinces. Glaciers covered most of the state. But<br />

the “Driftless Area” in southwestern Wisconsin<br />

has not been glaciated in the last two million years<br />

and forms a province with contiguous parts of<br />

Minnesota, Iowa, and Illinois. Thomson’s flora, for<br />

instance, shows the links of these two provinces<br />

through its mapping of disjunctive occurrences of<br />

northern lichens in southern microhabitats.<br />

In the historical development of scientific literature,<br />

the artificial floras of states prepare the way for<br />

national and continental floras.<br />

Unfortunately, there will be no volumes on the<br />

lichen flora of North America included among<br />

the many projected volumes of the Flora of North<br />

America which is slowly being published. In this,<br />

Australia is far ahead of the United States. So<br />

far twenty-six books of the Australian flora have<br />

been published since 1981, including three on the<br />

lichen flora, the latest of which is <strong>Volume</strong> 58A,<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s 3, in 2001. This volume is written mostly<br />

by Australian and New Zealand lichenologists<br />

including Dr. Patrick M. McCarthy and Dr. David<br />

J. Galloway, but also includes sections written<br />

by such eminent international authorities as Dr.<br />

Othmar Breuss, familiar to users of the Sonoran<br />

flora for his excellent work on Endocarpons and<br />

13

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

Placidiums. While probably not of much utilitarian<br />

value to <strong>California</strong>ns, <strong>Lichen</strong>s 3 nonetheless brings<br />

into perspective the global distribution of lichens,<br />

something that should always be kept in mind<br />

as one develops an understanding of one’s local<br />

flora and is an unavoidable fact in studying lichen<br />

genera or in the conservation of lichens.<br />

I did find one section very helpful, especially<br />

combined with Hasse’s flora and Bruce Ryan’s<br />

CD. McCarthy has written an absolutely excellent<br />

illustrated section on the global genus Verrucaria,<br />

which in the natural history of Australia represents<br />

a temperate intrusion into their flora.<br />

In fact, A. Aproot cites McCarthy’s “Trichotheliales<br />

and Verrucariaceae” from <strong>Lichen</strong>s 3 in the slim<br />

amount of references he used in preparing<br />

“Pyrenocarpous <strong>Lichen</strong>s and Related Non-<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>ized Ascomycetes from Taiwan,” published<br />

in the hardback Journal of the Hattori Botanical<br />

Laboratory, No. 93, <strong>2003</strong>. In an amazing feat, Andre<br />

Aproot and Laurens Sparrius, at the invitation of<br />

Prof. Ming-Jou Lai, collected in two weeks <strong>10</strong>1<br />

pyrenocarpous lichens and related ascomycetes,<br />

of which 96 were new records for Taiwan. And in<br />

those two weeks they went everywhere, from the<br />

tops of mountains at 3500 meters to the seashore<br />

to collect Verrucarias off volcanic outcrops and<br />

Verrucaria hocstetler off a coral reef. Taiwan “has<br />

become one of the best-known tropical areas for<br />

pyrenocarpous lichens in the world,” to quote a<br />

modest Aproot on page 156.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bryologist has published two important<br />

articles of special interest to <strong>California</strong>ns.<br />

In the last issue of 2002, Vol. <strong>10</strong>5(4), John W.<br />

Shead and Halmut Mayrhoffer’s “New Species of<br />

Rinodina (Physciaceae, <strong>Lichen</strong>ized Ascomycetes)<br />

from Western America,” describe seven new species<br />

with distributions in <strong>California</strong>. <strong>The</strong> descriptions of<br />

all the new western species are excellent and the<br />

drawings of spore development are of immediate<br />

practical value when you are analyzing your<br />

mount. Transcending the value of the new taxa<br />

is a key to the Rinodina species of Western North<br />

America which is very easy to use if you read the<br />

article carefully.<br />

In the first issue of <strong>The</strong> Bryologist in <strong>2003</strong>, Vol. 6(1),<br />

Clifford M. Wetmore published “<strong>The</strong> Caloplaca<br />

squamosa Group in North and Central America,”<br />

with fine color photographs. It is an elegant piece of<br />

work describing the diversity of this evolutionaryrelated<br />

group in four species with an easy-to-use<br />

key. To fully appreciate Wetmore’s achievement one<br />

should read the selection of specimens examined in<br />

the process of the formulation of each taxon.<br />

Of interest to all of us who have ever examined<br />

a lichen without ignoring those “anomalies,” is<br />

“<strong>Lichen</strong>icolous Fungi: Interactions, Evolution,<br />

and Biodiversity” by James D. Lawrey and Paul<br />

Diederich in <strong>The</strong> Bryologist, Vol. 6(1). In an exciting<br />

intellectual tour-de-force they roam through the<br />

subject of lichenicolous fungi throwing around<br />

facts, ideas, and hypotheses with the joy and agility<br />

of Cirque du Soleil acrobats juggling Ming dynasty<br />

vases. All serious lichen collectors should read<br />

and re-read this essay and consider developing a<br />

segregated collection of lichenicolous fungi because<br />

in the future these undetermined collections will be<br />

of value.<br />

Last but not least are two items printed in <strong>2003</strong> but<br />

probably now unavailable. Frank Burgatz’s ASU<br />

Herbarium <strong>Lichen</strong> Calendar of <strong>2003</strong> is graced with<br />

beautiful pictures of Sonoran species. A great deal<br />

were the sturdy T-shirts sold by the Northwestern<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>ologists. <strong>The</strong>y feature Letharia columbiana,<br />

looking like the mandala of an alien civilization.<br />

<strong>The</strong> lichen design is absolutely stunning in yellow<br />

on a black T-shirt. I could have sold five straight<br />

off on the last Nature Conservancy walk I went<br />

on. If they are still available, buy one. Amiable<br />

Erin Martin has done a wonderful job handling the<br />

promotion and sales.<br />

<strong>Lichen</strong>s of Wisconsin and issues of the Bryologists<br />

are available through the ABLS website at http:<br />

//www.unomaha.edu/~abls/<br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the Hattori Botanical Laboratory<br />

is available through the Hattori website at http:<br />

//www7.ocn.ne.jp/~hattorib/<br />

For Northwest <strong>Lichen</strong>ologist T-shirts try http://<br />

www.proaxis.com/~mccune/nwl.htm<br />

14

News and Notes<br />

<strong>CALS</strong> Field trip to Redwood Regional Park,<br />

General Meeting, and Birthday celebration<br />

January 11, <strong>2003</strong><br />

Redwood Regional Park is one of the many parks<br />

in the East Bay Regional Park district. Situated<br />

above Skyline Blvd. in Oakland, many trails have<br />

spectacular views of the San Francisco Bay. Also,<br />

the Bay Area Ridge trail runs lengthwise through<br />

the park. Twelve lichen enthusiasts met at the<br />

Redwood Gate on the east side of the park. We<br />

focused on lichen ecology. Close to the parking<br />

lot was a large grassy area with some non-native<br />

trees. A creek lined with willows was close by.<br />

A small amount of chaparral scrub was on the<br />

hillside. We looked at various trees in the grassy,<br />

open area. Noticeable was the predominance of<br />

the Xanthorian assemblage on the non-native trees<br />

especially on the lower part of the trunks. Xanthoria<br />

parietina was present and Physcia adscendens was<br />

very common. <strong>The</strong> willows along the creek had<br />

many more species and numbers of lichens than<br />

any of the other trees we observed. <strong>The</strong> lichens<br />

found there were common in the Bay area:<br />

Parmotrema chinense, Evernia prunastri, Parmelia<br />

sulcata, Punctilia subrudecta, Flavoparmelia caperata,<br />

Physconia isidiigera, Xanthoria candelaria, Melanelia<br />

sp., Heterodermia leucomelaena, Hypotrachyna revoluta,<br />

Usnea sp., and a variety of crustose lichens. Even<br />

the picnic tables where we had lunch had lichen<br />

growth.<br />

After lunch, we drove to a Serpentine prairie in<br />

the park and walked a short trail. Again, Xanthoria<br />

species were very common on the shrubs along the<br />

path.<br />

Participating were Arlyn Christopherson, Irene<br />

Winston, Shelly Benson, Cherie Bratt, Janet and<br />

Richard Doell, Bill Ferguson, Bill Hill, Kathy<br />

Faircloth, Susanne Altermann, Judy Robertson,<br />

and Kuni Kitajima.<br />

Following the field trip we drove to the Brickyard<br />

Landing Clubhouse in Pt. Richmond.<br />

We held our annual General Meeting followed by a<br />

delicious pot luck dinner. Some of the dishes were<br />

Coq au Vin, stuffed squash, spinach salad, polenta,<br />

and a salad of black rice, apples, and nuts. After<br />

dinner, we had a Birthday cake to celebrate the 9 th<br />

anniversary of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

After the the eating was over, the board members<br />

present held their board meeting.<br />

It was a special day for all attending.<br />

Reported by Judy Robertson.<br />

<strong>CALS</strong> field trip to Fairfield Osborne Preserve,<br />

Sonoma County<br />

March 1, <strong>2003</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> day was mostly sunny and slightly cool when<br />

14 people met in the SSU parking lot to carpool to<br />

Fairfield Osborne Preserve, named in honor of the<br />

pioneer ecologist, Fairfield Osborne. <strong>The</strong> preserve<br />

was established by the Roth Family in 1972. It was<br />

acquired by <strong>The</strong> Nature Conservancy, but is now<br />

owned and managed by Sonoma State University.<br />

A group of dedicated volunteers are working to<br />

protect and restore the natural communities on the<br />

Preserve as well as foster ecological understanding<br />

through education.<br />

Our group spent much time at the large valley oak<br />

near the parking lot. At least 25 species of lichens<br />

were counted on trunk, branches and twigs. With<br />

a simple key, Judy led the participants through<br />

identification of the most common lichens present:<br />

Flavopunctelia flaventior, and Flavoparmelia caperata,<br />

Parmelia sulcata and Parmotrema chinense, Physcia<br />

adscendens, Physconia sp., Xanthoria polycarpa and<br />

Teloschistes chrysophthalmus.<br />

We walked up the trail on a nearby hillside looking<br />

for lichens found on soil banks. At least 4 species<br />

of Cladonia, 2 species of Leptogium, Leptochidium<br />

albociliatum, and 2 species of Peltigera were on<br />

display. We also observed Diploschistes muscorum<br />

15

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>10</strong>(1), <strong>2003</strong><br />

parasitizing many of the Cladonia patches.<br />

We headed to the vernal pool for lunch. Again<br />

using the simple key to lichens of Sonoma County,<br />

we identified Hypogymnia imshaugii and H. tubulosa.<br />

Other species on the oaks were: Physconia americana,<br />

Physcia stellaris, and Hypotrachyna revoluta.<br />

Across the small bridge we found Normandina<br />

pulchella and Waynea stoechadiana, on the trunk<br />

of a small live oak with Lobaria pulmonaria,<br />

Pseudocyphellaria anthraspis, P. anomola and<br />

Nephroma helveticum nearby.<br />

As we returned on the same route, we observed the<br />

crustose lichens on the rocks. Common was Lecidea<br />

tessellata, with a variety of Aspicilia sp., Caloplaca sp.,<br />

and Xanthoparmelia sp.<br />

This was a very enjoyable day for all participating:<br />

Bill Hill, Kathy Faircloth, Earl Alexander, Don<br />

Brittingham, Janet and Richard Doell, Jessica<br />

Wilson, Daniel George, Devi Rao, Irene Winston,<br />

Walter Levison, Celia Chong, Kuni and leader Judy<br />

Robertson<br />

In addition to the lichens listed above, these species<br />

are known to occur at Fairfield Osborne Preserve:<br />

Caloplaca chrysophthalma Degel<br />

Candelaria concolor (Dickson) Stein<br />

Cladonia cervicornis subsp. verticillata (Hoffm.) Ahti<br />

Cladonia chlorophaea (Florke ex Sommerf.) Sprengel<br />

Cladonia fimbriata (L.) Fr.<br />

Cladonia furcata (Hudson) Schrader<br />

Cladonia macilenta Hoffm.<br />

Cladonia ochrochlora Florke<br />

Cladonia pyxidata (L.) Hoffm.<br />

Collema furfuracium (Arnold) Du Rietz<br />

Collema nigrescens (Hudson) DC.<br />

Dermatocarpon miniatum (L.) W. Mann<br />

Diploschistes scruposus (Schreber) Norman<br />

Evernia prunastri (L.) Ach.<br />

Fuscopannaria leucostictoides (Ohlsson) P.M. Jorg.<br />

Graphis scripta (L.) Ach.<br />

Hyperphyscia adglutinata (Florke) H. Mayrh. &<br />

Poelt<br />

Hypogymnia enteromorpha (Ach.) Nyl.<br />

Hypogymnia physodes (L.) Nyl.<br />

Lecanora muralis (Schreber) Rabenh.<br />

Lecidea atrobrunnea (Ramond ex Lam. & DC.)<br />

Schaerer<br />

Leptogium corniculatum (Hoffm.) Minks<br />

Leptogium lichenoides (L.) Zahlbr.<br />

Leptogium corniculatum (Hoffm.) Minks<br />