Rapid survey of the birds of the Atewa Range Forest Reserve, Ghana

Rapid survey of the birds of the Atewa Range Forest Reserve, Ghana

Rapid survey of the birds of the Atewa Range Forest Reserve, Ghana

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

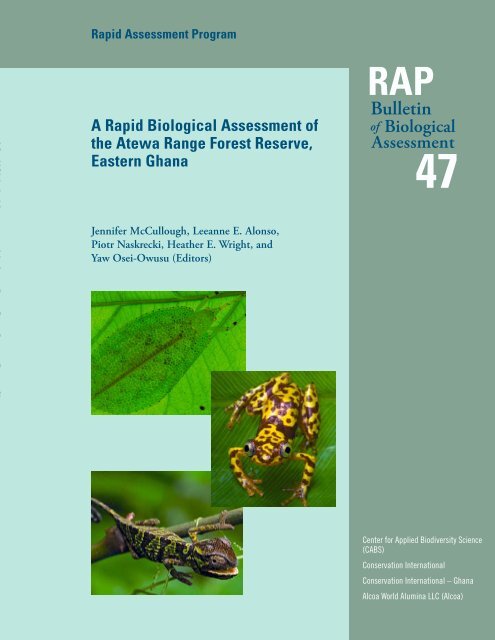

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>,<br />

Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

RAP<br />

Bulletin<br />

<strong>of</strong> Biological<br />

Assessment<br />

47<br />

Jennifer McCullough, Leeanne E. Alonso,<br />

Piotr Naskrecki, Hea<strong>the</strong>r E. Wright, and<br />

Yaw Osei-Owusu (Editors)<br />

Center for Applied Biodiversity Science<br />

(CABS)<br />

Conservation International<br />

Conservation International – <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Alcoa World Alumina LLC (Alcoa)

Cover photos (Piotr Naskrecki)<br />

Top: Sylvan katydid (Mustius afzelli)<br />

Center: Frog (Afrixalus vebekensis)<br />

Botton: Chameleon (Chamaeleo gracilis)

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>,<br />

Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

RAP<br />

Bulletin<br />

<strong>of</strong> Biological<br />

Assessment<br />

47<br />

Jennifer McCullough, Leeanne E. Alonso,<br />

Piotr Naskrecki, Hea<strong>the</strong>r E. Wright, and<br />

Yaw Osei-Owusu (Editors)<br />

Center for Applied Biodiversity Science (CABS)<br />

Conservation International<br />

Conservation International – <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Alcoa World Alumina LLC (Alcoa)

The RAP Bulletin <strong>of</strong> Biological Assessment is published by<br />

Conservation International<br />

Center for Applied Biodiversity Science<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA USA 22202<br />

Tel : 703-341-2400<br />

www.conservation.org<br />

www.biodiversityscience.org<br />

Editors: Jennifer McCullough, Leeanne E. Alonso, Piotr Naskrecki, Hea<strong>the</strong>r E. Wright and Yaw Osei-Owusu<br />

Design: Glenda Fabregas<br />

Map: Mark Denil<br />

Photography: Piotr Naskrecki<br />

RAP Bulletin <strong>of</strong> Biological Assessment Series Editors:<br />

Jennifer McCullough and Leeanne E. Alonso<br />

ISBN #978-1-934151-09-9<br />

© 2007 Conservation International<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> Congress Card Catalog Number 2007940630<br />

Conservation International is a private, non-pr<strong>of</strong>it organization exempt from federal income tax under section<br />

501c(3) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Internal Revenue Code.<br />

The designations <strong>of</strong> geographical entities in this publication, and <strong>the</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> material, do not<br />

imply <strong>the</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> any opinion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Conservation International or its supporting<br />

organizations concerning <strong>the</strong> legal status <strong>of</strong> any country, territory, or area, or <strong>of</strong> its authorities, or concerning <strong>the</strong><br />

delimitation <strong>of</strong> its frontiers or boundaries.<br />

Any opinions expressed in <strong>the</strong> RAP Bulletin <strong>of</strong> Biological Assessment Series are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> writers and do not<br />

necessarily reflect those <strong>of</strong> Conservation International or its co-publishers.<br />

RAP Bulletin <strong>of</strong> Biological Assessment was formerly RAP Working Papers. Numbers 1-13 <strong>of</strong> this series were<br />

published under <strong>the</strong> previous series title.<br />

Suggested citation:<br />

McCullough, J., L.E. Alonso, P. Naskrecki, H.E. Wright and Y. Osei-Owusu (eds.). 2007. A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>. RAP Bulletin <strong>of</strong> Biological Assessment 47.<br />

Conservation International, Arlington, VA.

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Participants and Authors..................................................5<br />

Organizational Pr<strong>of</strong>iles.....................................................7<br />

Acknowledgements...........................................................9<br />

Report at a Glance...........................................................10<br />

Executive Summary.........................................................13<br />

Map and Photos................................................................31<br />

Chapters.............................................................................35<br />

Chapter 1............................................................................35<br />

An ecological, socio-economic and conservation overview <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Chapter 2............................................................................41<br />

The botanical diversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong><br />

Carel C. H. Jongkind<br />

Chapter 3............................................................................43<br />

A rapid botanical <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

D.E.K.A Siaw and Jonathan Dabo<br />

Chapter 4............................................................................50<br />

Dragonflies and Damselflies (Odonata) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Klaas-Douwe B. Dijkstra<br />

Chapter 5............................................................................55<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> butterflies in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Kwaku Aduse-Poku and Ernestina Doku-Marfo<br />

Chapter 6 ...........................................................................61<br />

Additional comments on butterflies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upland Evergreen<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Torben Larsen<br />

Chapter 7............................................................................63<br />

The katydids <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Piotr Naskrecki<br />

Chapter 8..........................................................................69<br />

A rapid assessment <strong>of</strong> fishes in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

E. K. Abban<br />

Chapter 9..........................................................................76<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> amphibians from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern Region, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

N’goran Germain Kouamé, Caleb Ofori Boateng and<br />

Mark-Oliver Rödel<br />

Chapter 10........................................................................84<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>birds</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Ron Demey and William Ossom<br />

Chapter 11........................................................................90<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> small mammals from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern Region, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Natalie Weber and Jakob Fahr<br />

Chapter 12........................................................................99<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> large mammals from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern Region, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Moses K<strong>of</strong>i Sam, Kwaku Oduro Lokko, Emmanuel Akom and<br />

John Nyame<br />

Chapter 13......................................................................103<br />

A rapid <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> primates from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Nicolas Granier and Vincent Awotwe-Pratt<br />

Gazetteer........................................................................113<br />

Appendices...................................................................114<br />

Appendix 1.....................................................................114<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Vascular Plants known from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong><br />

Carel Jongkind<br />

Appendix 2.....................................................................130<br />

List <strong>of</strong> plant species recorded during <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

RAP <strong>survey</strong>, June 2006<br />

D.E.K.A Siaw and Jonathan Dabo<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>

Appendix 3.......................................................................137<br />

Checklist <strong>of</strong> Odonata recorded from <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Klaas-Douwe B. Dijkstra<br />

Appendix 4.......................................................................143<br />

Checklist <strong>of</strong> butterflies from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong> with a list <strong>of</strong> those collected at each site<br />

during <strong>the</strong> 2006 RAP <strong>survey</strong><br />

Kwaku Aduse-Poku and Ernestina Doku-Marfo<br />

Appendix 5.......................................................................171<br />

Ant species collected from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong> during <strong>the</strong> 2006 RAP <strong>survey</strong><br />

Lloyd R. Davis Jr. and Leeanne E. Alonso<br />

Appendix 6.......................................................................173<br />

List <strong>of</strong> bird species recorded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Ron Demey and William Ossom<br />

Appendix 7.......................................................................178<br />

Bats collected during <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> and<br />

deposited in <strong>the</strong> research collection <strong>of</strong> Jakob Fahr,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Ulm<br />

Natalie Weber and Jakob Fahr<br />

Appendix 8.......................................................................179<br />

Shrews and rodents collected during <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> RAP<br />

<strong>survey</strong> and deposited in <strong>the</strong> collections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Zoologisches<br />

Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Bonn (ZFMK)<br />

Natalie Weber and Jakob Fahr<br />

Appendix 9.......................................................................180<br />

List <strong>of</strong> small mammal species reported from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> in previous <strong>survey</strong>s<br />

Natalie Weber and Jakob Fahr<br />

Appendix 10.....................................................................181<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> Initial Biodiversity Assessment<br />

and Planning (IBAP) Working Group Results from <strong>the</strong><br />

Consultative Workshop held at Okyehene’s Palace, Kibi<br />

Appendix 11.....................................................................183<br />

Participants in <strong>the</strong> Consultative Workshop held at<br />

Okyehene’s Palace, Kibi<br />

Appendix 12.....................................................................185<br />

IUCN Red-listed amphibian, bird and mammal species<br />

recorded from 16 reserves studied during West African RAP<br />

<strong>survey</strong>s<br />

<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Participants and Authors<br />

K<strong>of</strong>i Abban (freshwater fish)<br />

Water Research Institute<br />

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)<br />

P.O. Box M-32<br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. csir_wri@yahoo.com<br />

Kwaku Aduse-Poku (butterflies)<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Renewable Natural Resources (FRNR)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. kadusepoku@yahoo.com<br />

Leeanne E. Alonso (ants, editor)<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program (RAP)<br />

Conservation International<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA 22202<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

Email. l.alonso@conservation.org<br />

Okyeame Ampadu-Agyei (CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> host)<br />

Country Director-<strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Conservation International-<strong>Ghana</strong><br />

P.O. Box KAPT 30426<br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. Oampadu-agyei@conservation.org<br />

Vincent Awotwe-Pratt (primates-field assistant)<br />

University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. vincepratt@yahoo.com<br />

Caleb Ofori Boateng (amphibians-field assistant)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. caleb<strong>of</strong>ori@gmail.com<br />

Kwame Botchway (small mammals-field assistant)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. obotwe@yahoo.com<br />

Jonathan Dabo (plants)<br />

<strong>Forest</strong>ry Research Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> (FORIG)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Box 63 Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. Jdabo@forig.org<br />

Lloyd R. Davis Jr. (ants)<br />

3920 NW 36th Place<br />

Gainesville, FL 32606<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

Email. ants@gru.net<br />

Ron Demey (<strong>birds</strong>)<br />

Van Der Heimstraat 52<br />

2582 SB Den Haag, THE NETHERLANDS<br />

Email. rondemey@compuserve.com<br />

Klaas-Douwe B. Dijkstra (dragonflies)<br />

Gortestraat 11<br />

2311 MS Leiden, THE NETHERLANDS<br />

Email. dijkstra@nnm.nl<br />

Ernestina Doku-Marfo (butterflies-field assistant)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. tinammarfo@yahoo.com<br />

Jakob Fahr (contributing author)<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Experimental Ecology (Bio III)<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Ulm<br />

Albert-Einstein Allee 11<br />

D-89069 Ulm, GERMANY<br />

Email. jakob.fahr@uni.ulm.de<br />

Nicolas Granier (primates)<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Zoology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Liege<br />

2 rue Vanloo<br />

13100 Aix-en-Provence, FRANCE<br />

Email. nicogranier@yahoo.fr<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>

Paticipants and Authors<br />

N’Goran Germain Kouamé (amphibians)<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Aquatic Biology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Abobo-Adjame<br />

02 BP 801 Abidjan 02, CÔTE D’IVOIRE<br />

Email. ngoran_kouame@yahoo.fr<br />

Carel Jongkind (contributing author)<br />

Wageningen University<br />

Tarthorst 145<br />

6708 HG Wageningen, NETHERLANDS<br />

Email. Carel.Jongkind@wur.nl<br />

Torben Larsen (contributing author)<br />

Butterflies <strong>of</strong> West Africa<br />

358 Coldharbour Lane<br />

London SW9 8PL, UK<br />

Email. torbenlarsen@compuserve.com<br />

Kwaku Oduro Lokko (large mammals-field assistant)<br />

University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. kwakul@yahoo.com<br />

Jennifer McCullough (editor)<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program (RAP)<br />

Conservation International<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA 22202<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

Email. j.mccullough@conservation.org<br />

Piotr Naskrecki (invertebrates, editor)<br />

Director, Invertebrate Diversity Initiative (IDI)<br />

Conservation International<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Comparative Zoology<br />

Harvard University<br />

26 Oxford St.<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

Email. pnaskrecki@conservation.org<br />

William Kwao Ossom (<strong>birds</strong>)<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Renewable Natural Resources (FRNR)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. wwkossom@yahoo.com<br />

Mark-Oliver Rödel (amphibians)<br />

Curator <strong>of</strong> Herpetology<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History<br />

Invalidenstr. 43<br />

10099 Berlin, GERMANY<br />

Email. mo.roedel@museum.hu-berlin.de<br />

Moses K<strong>of</strong>i Sam (large mammals)<br />

<strong>Forest</strong>ry Commission<br />

Wildlife Division<br />

P.O. Box 1457<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. osmo288@yahoo.co.uk<br />

D.E.K.A. Siaw (plants)<br />

<strong>Forest</strong>ry Research Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> (FORIG)<br />

Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology<br />

(KNUST)<br />

Box 63<br />

Kumasi, GHANA<br />

Email. dekasiaw@yahoo.co.uk<br />

Nana Abena Somaa (small mammals-field assistant/<br />

coordination)<br />

Conservation International-<strong>Ghana</strong><br />

P.O. Box KAPT 30426<br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. n.somaa@conservation.org<br />

Natalie Weber (small mammals)<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Experimental Ecology<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Ulm<br />

Albert-Einstein-Allee 11<br />

89069 Ulm, GERMANY<br />

Email. natalieweber@gmx.de<br />

Hea<strong>the</strong>r E. Wright (coordination)<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program<br />

Conservation International<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA 22202<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

Email. Hea<strong>the</strong>r.Wright@moore.org<br />

Yaw Osei-Owusu (coordination, editor)<br />

Conservation International-<strong>Ghana</strong><br />

P.O. Box KAPT 30426<br />

Accra, GHANA<br />

Email. yosei-owusu@CI.conservation.org<br />

<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Organizational Pr<strong>of</strong>iles<br />

Conservation International<br />

Conservation International (CI) is an international, nonpr<strong>of</strong>it organization based in Washington,<br />

DC. CI believes that <strong>the</strong> Earth’s natural heritage must be maintained if future generations<br />

are to thrive spiritually, culturally and economically. Our mission is to conserve <strong>the</strong> Earth’s living<br />

heritage, our global biodiversity, and to demonstrate that human societies are able to live<br />

harmoniously with nature.<br />

Conservation International<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA 22202<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

tel. 1-703-341-2400<br />

fax. 1-703-553-0654<br />

www.conservation.org<br />

Conservation International – <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Conservation International <strong>Ghana</strong>’s work started in 1990 with <strong>the</strong> Kakum National Park,<br />

where <strong>the</strong> habitat <strong>of</strong> globally threatened species was secured against fur<strong>the</strong>r degradation and<br />

species extinction through innovative ecotourism development. To fur<strong>the</strong>r secure Kakum<br />

National Park, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> implemented <strong>the</strong> Cocoa Agro-forestry Programme in partnership<br />

with Kuapa Kokoo, assisting cocoa farmers within <strong>the</strong> Kakum Conservation Area to adopt ecologically<br />

sustainable agronomic practices for increased production. This agr<strong>of</strong>orestry initiative<br />

has provided a buffer zone and additional wildlife habitat for <strong>the</strong> threatened species within <strong>the</strong><br />

Park. As a result <strong>of</strong> CI-<strong>Ghana</strong>’s interventions, Kakum National Park currently receives about<br />

80,000 visitors annually, contributing significantly to <strong>the</strong> socio-economic development <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> project site at Kakum National Park, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> has expanded its focus to <strong>the</strong><br />

national level. CI-<strong>Ghana</strong>’s work focuses on preventing species extinction, increasing protection<br />

and improving management <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remaining forest fragments, and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> biodiversity<br />

corridors. To curb <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> species extinction in <strong>Ghana</strong>, as a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bushmeat<br />

trade, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> carried out a two-year nation-wide bushmeat campaign. This was done in<br />

partnership with <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Division, Atomic Energy Commission, <strong>Ghana</strong> Standards Board<br />

and Food and Drugs Board. O<strong>the</strong>rs included <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> Food and Agriculture and <strong>the</strong><br />

Environmental Protection Agency <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>. In partnership with <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment<br />

and Science, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> provided technical support, secretariat and funding for <strong>the</strong> completion<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Biodiversity Strategy for <strong>Ghana</strong>. To ensure <strong>the</strong> effective implementation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Strategy, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> also provided technical support for <strong>the</strong> formulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Action<br />

Plan. Currently, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> is represented on <strong>the</strong> National Biodiversity Committee in <strong>Ghana</strong>.<br />

In December 1999, CI-<strong>Ghana</strong> facilitated a conservation priority-setting workshop that built a<br />

broad-based consensus on priorities for biodiversity conservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upper Guinea forest<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>

ecosystem through active participation <strong>of</strong> 146 individuals<br />

from 90 institutions. Government, NGOs and private sector<br />

participants developed a common platform to guide and coordinate<br />

new investment and conservation at various scales<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

Conservation International <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

P.O. Box KA 30426<br />

Airport, Accra<br />

GHANA<br />

tel. +233 21 773893 / 780906<br />

fax. +233 21 762009<br />

email. cioaa@ghana.com<br />

Center for Applied Biodiversity Science (CABS)<br />

The mission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Center for Applied Biodiversity Science<br />

(CABS) is to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> Conservation International<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r institutions to identify and respond to<br />

elements that threaten <strong>the</strong> earth’s biological diversity. CABS<br />

collaborates with universities, research centers, multilateral<br />

government and non-governmental organizations to address<br />

<strong>the</strong> urgent global-scale concerns <strong>of</strong> conservation science.<br />

CABS researchers are using state-<strong>of</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-art technology to<br />

collect data, consult with o<strong>the</strong>r experts around <strong>the</strong> world,<br />

and disseminate results. In this way, CABS research is an<br />

early warning system that identifies <strong>the</strong> most threatened<br />

regions before <strong>the</strong>y are destroyed. In addition, CABS provides<br />

tools and resources to scientists and decisions-makers<br />

that help <strong>the</strong>m make informed choices about how best to<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> hotspots.<br />

Alcoa World Alumina LLC (Alcoa)<br />

As one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’s leading aluminium producers with operations<br />

in a number <strong>of</strong> countries throughout <strong>the</strong> world Alcoa<br />

has given priority to addressing environmental concerns<br />

in its operations and developments. Alcoa has implemented<br />

a sustainability strategy that it applies in its processing operations<br />

and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> new projects such as <strong>the</strong> proposed<br />

refinery in Guinea. The strategy is based on <strong>the</strong> goal<br />

<strong>of</strong> simultaneously achieving financial success, environmental<br />

excellence, and social responsibility through partnerships in<br />

order to deliver net long-term benefits to shareholders, employees,<br />

customers, suppliers, and <strong>the</strong> communities in which<br />

Alcoa operates.<br />

Alcoa World Alumina LLC<br />

201 Isabella Street<br />

Pittsburgh, PA<br />

15212-5858<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

tel. 412-553-4545<br />

fax. 412-553-4498<br />

www.alcoa.com<br />

Conservation International<br />

2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500<br />

Arlington, VA 22202<br />

UNITED STATES<br />

www.biodiversityscience.org<br />

<br />

<strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Acknowledgements<br />

The success <strong>of</strong> this RAP <strong>survey</strong> would not have been possible without <strong>the</strong> collective effort <strong>of</strong> many<br />

dedicated individuals and organizations. The RAP team would like to thank <strong>the</strong> following people and<br />

groups for helping to make this RAP <strong>survey</strong> a success. First <strong>of</strong> all, we thank <strong>the</strong> <strong>Forest</strong>ry Commission<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> for permitting access to <strong>the</strong> forest reserves and we are especially grateful for <strong>the</strong> collaboration<br />

from Okyehene, Osagyefo Amoatia Ofori Panin and chiefs and elders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fringe communities surrounding<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong>.<br />

We appreciate <strong>the</strong> strong commitment shown by ALCOA’s Eric Black, Anita Roper, Kevin Lowery,<br />

John Gardner, Augustus Amegashie, Oumar Toguyeni, and Ibrahima Danso to incorporate biodiversity<br />

conservation into <strong>the</strong>ir project plans in <strong>Ghana</strong>. We are fur<strong>the</strong>rmore grateful for ALCOA’s financial support<br />

to conduct this <strong>survey</strong> in such a biologically unique area.<br />

We thank <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> CI-<strong>Ghana</strong>, especially <strong>the</strong> Country Director, Okyeame Ampadu-Agyei, Emmanuel<br />

Owusu, Philip Badger for assistance with permits, logistics and equipment, Nana Abena-Somaa<br />

for logistical support and help in <strong>the</strong> field, and Yaw Osei-Owusu for his leadership and dedication in<br />

<strong>the</strong> field.<br />

Local assistants and field guides were <strong>of</strong> invaluable help during field work, including Joshua Akyeaner,<br />

Daniel Koranteng, Agyare Duodu, Kwabena Frempong, Alex Boapeah and Eric Boadi. Their<br />

hard work, dedication and <strong>the</strong>ir inspiring companionship helped make this expedition a success. Special<br />

thanks to our cooks, Ohenewaa Boadu Portia and Teye Maccarthy, who kept us nourished and well fed.<br />

Their good nature and cooking gave us <strong>the</strong> energy to carry out our long days <strong>of</strong> fieldwork. We also owe<br />

a debt <strong>of</strong> gratitude to our drivers, Collins Nuamah, Kwesi Amissah and Eric Mensah, and our videographer<br />

Isaac Amissah and his assistant Jacob Zong.<br />

The RAP participants thank Leeanne Alonso, Piotr Naskrecki, Hea<strong>the</strong>r Wright and Peter Hoke <strong>of</strong><br />

Conservation International for <strong>the</strong> invitation to participate to this RAP <strong>survey</strong>. The editors thank Mark<br />

Denil <strong>of</strong> CI’s Conservation Mapping Program and both Glenda Fabregas and Kim Meek for <strong>the</strong>ir attention<br />

to detail and patience in designing RAP publications.<br />

This project was made possible through Conservation International’s Center for Environmental<br />

Leadership in Business (CELB) and West Africa programs, and we particularly thank Marielle Canter<br />

and Jessica Donovan for <strong>the</strong>ir input and support throughout this RAP <strong>survey</strong>.<br />

The primate group wishes to thank Vincent for field assistance, as well as <strong>the</strong> many local workers,<br />

especially Joshua Akyeanor (our guide from Tete), as well as all <strong>the</strong> RAP participants. Thanks also to <strong>the</strong><br />

local villagers for participating in interviews.<br />

The butterfly team wishes to thank Yaw Osei-Owusu <strong>of</strong> CI- <strong>Ghana</strong> for <strong>the</strong> opportunity to take part<br />

in <strong>the</strong> expedition. They are indebted to Dr. Torben B. Larsen for his valuable comments on <strong>the</strong> manuscript<br />

and continual assistance on butterfly species identification. They also thank all <strong>the</strong> team members<br />

for <strong>the</strong> fun and good time at <strong>the</strong> muddy camp sites.<br />

The amphibian team thanks Nana Abena, Leeanne E. Alonso, Piotr Naskrecki, Yaw Osei-Owusu,<br />

and Hea<strong>the</strong>r Wright, as well as all o<strong>the</strong>r RAP participants, for <strong>the</strong>ir support.<br />

The small mammal team thanks Kwame Botchway and Nana Abena Somaa for <strong>the</strong>ir dedicated assistance<br />

in <strong>the</strong> field. The identification <strong>of</strong> shrews and murids by Rainer Hutterer (ZFMK) is highly appreciated.<br />

Jan Decher, University <strong>of</strong> Vermont, provided helpful information and comments on <strong>the</strong> manuscript.<br />

Laurent Granjon, IRD Montpellier, and Mark-Oliver Rödel, University <strong>of</strong> Würzburg, <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

suggestions on <strong>the</strong> manuscript. Analysis and publication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> data is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> BIOLOG-program <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> German Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education and Science (BMBF; project W09 BIOTA-West, 01 LC 0411).<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>

Report at a Glance<br />

Expedition Dates<br />

6 – 24 June 2006<br />

Area Description<br />

The <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> (<strong>Atewa</strong>) was established as a national forest reserve in 1926<br />

and has since been designated as a Globally Significant Biodiversity Area (GSBA) and an<br />

Important Bird Area (IBA) (Abu-Juam et al. 2003). The <strong>Atewa</strong> mountain range, located in<br />

south-eastern <strong>Ghana</strong>, runs roughly from north to south and is characterized by a series <strong>of</strong><br />

plateaus. One <strong>of</strong> only two reserves in <strong>Ghana</strong> with Upland Evergreen forest (Hall and Swaine<br />

1981, Abu-Juam et al. 2003), <strong>Atewa</strong> represents about 33.5% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remaining closed forest<br />

in <strong>Ghana</strong>’s Eastern Region. <strong>Atewa</strong> is home to many endemic and rare species, including black<br />

star plant species and several endemic butterfly species (Hawthorne 1998, Larsen 2006). Seasonal<br />

marshy grasslands, swamps and thickets on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> plateaus are nationally unique<br />

(Hall and Swaine 1981).<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> has long been recognized as a nationally important reserve because its<br />

mountains contain <strong>the</strong> headwaters <strong>of</strong> three river systems, <strong>the</strong> Ayensu, Densu and Birim rivers.<br />

These three rivers are <strong>the</strong> most important sources <strong>of</strong> domestic, agricultural and industrial water<br />

for local communities as well as for many <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>’s major population centers, including Accra.<br />

The RAP <strong>survey</strong> was conducted around three sites within <strong>Atewa</strong>: Atiwiredu<br />

(6°12’24.7’’N, 0°34’37.2’’W, 795 m); Asiakwa South (6°15’44.3’’N, 0°33’18.8’’W, 690 m);<br />

and Asiakwa North (6°16’16.4’’N, 0°33’52.8’’W, 769 m). The RAP sites were chosen to coincide<br />

with areas <strong>of</strong> potentially high biodiversity and concentrated bauxite deposits that had<br />

been earmarked for exploitation activities by ALCOA. The fish and dragonfly teams also sampled<br />

streams, rivers and o<strong>the</strong>r freshwater sites outside <strong>the</strong> reserve that are part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> watershed<br />

originating within <strong>Atewa</strong>.<br />

Expedition Objectives<br />

In addition to high biodiversity, <strong>Atewa</strong> is known to harbor mineralogical wealth including<br />

both gold and bauxite deposits. The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> granted an exploration license<br />

to ALCOA to prospect within <strong>Atewa</strong> for bauxite deposits. Due to <strong>Atewa</strong>’s classification as a<br />

GSBA, ALCOA initiated an agreement with Conservation International (CI) to assist <strong>the</strong>m<br />

in better understanding <strong>the</strong> area’s biodiversity context. The aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> agreement was to provide<br />

significant gains for biodiversity conservation, industry, government, and <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>.<br />

Specifically, <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> aimed to derive a brief but thorough overview <strong>of</strong> species<br />

diversity in <strong>Atewa</strong>, to evaluate <strong>the</strong> area’s relative conservation importance, to provide management<br />

and research recommendations, and to increase awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> ecosystems in<br />

order to promote <strong>the</strong>ir conservation.<br />

Overall RAP results<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> show that <strong>Atewa</strong> is an exceptionally important site for national<br />

and global biodiversity conservation. All taxonomic groups <strong>survey</strong>ed were comprised almost<br />

10 <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Report at a Glance<br />

exclusively <strong>of</strong> forest species, indicating an intact forest ecosystem,<br />

which is a highly unusual and (from a conservation<br />

perspective) highly significant finding for West Africa, where<br />

most forests are highly fragmented and disturbed.<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> harbors a high diversity <strong>of</strong> species especially <strong>of</strong><br />

butterflies (<strong>Atewa</strong> has <strong>the</strong> highest butterfly diversity <strong>of</strong> any<br />

site in <strong>Ghana</strong>), dragonflies, katydids, <strong>birds</strong>, and plants. Included<br />

among <strong>the</strong> many rare and threatened species at <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

are six black star plant species, six bird species <strong>of</strong> global conservation<br />

concern, two primates and 10 o<strong>the</strong>r large mammals,<br />

and a high proportion <strong>of</strong> threatened amphibian species<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> Critically Endangered frog Conraua derooi, for<br />

which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> is likely to hold <strong>the</strong> largest remaining<br />

populations.<br />

The unique and diverse species assemblages documented<br />

during <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong>, especially <strong>of</strong> amphibians, Odonata<br />

(dragonflies and damselflies) and fishes, all depend on <strong>the</strong><br />

clean and abundant water that originates in <strong>Atewa</strong> for <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

survival. <strong>Ghana</strong>ians around <strong>Atewa</strong> and as far as Accra also<br />

depend on this water source, which is provided by <strong>the</strong> plateau<br />

formations which soak up rain and mist and <strong>the</strong>n hold,<br />

clean and discharge fresh water.<br />

Conservation Conclusions and Recommendations<br />

This RAP <strong>survey</strong> confirms that <strong>Atewa</strong> is a site <strong>of</strong> extremely<br />

high importance for global biodiversity conservation and<br />

should be protected in its entirety. <strong>Atewa</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

remaining forest blocks in <strong>Ghana</strong> and contains <strong>Ghana</strong>’s<br />

last intact stand <strong>of</strong> Upland Evergreen forest. The only<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r forest <strong>of</strong> this type in <strong>Ghana</strong>, in <strong>the</strong> Tano Ofin <strong>Forest</strong><br />

<strong>Reserve</strong>, is smaller and significantly more disturbed. <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

is also an extremely important watershed – holding, cleaning<br />

and discharging freshwater that supports a rich biodiversity<br />

and provides clean water to millions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>ians. There is<br />

no o<strong>the</strong>r place like <strong>Atewa</strong> in <strong>Ghana</strong>.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> and previous<br />

studies, we <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>the</strong> following two principal conservation<br />

recommendations. See <strong>the</strong> Executive Summary section for<br />

more details and for management recommendations.<br />

• Within <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Government<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> should delimit and establish an integrally<br />

protected area with high protection status, such<br />

as a National Park, that includes all remaining intact<br />

Upland Evergreen forest, especially on <strong>the</strong> plateaus. A<br />

buffer zone covering <strong>the</strong> more disturbed slopes and valleys<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve should be established surrounding <strong>the</strong><br />

core protected area.<br />

• To ensure <strong>the</strong> sustainable protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong>, alternative<br />

incomes for <strong>the</strong> local communities, particularly<br />

in Kibi, should be developed to reduce existing or<br />

potential dependence on extractive industries and forest<br />

products from <strong>Atewa</strong>. This should be done as a collaborative<br />

effort between government, private, NGO,<br />

scientific, development, and community groups.<br />

References<br />

Abu-Juam, M., Obiaw, E., Kwakye, Y., Ninnoni, R., Owusu,<br />

E. H. and Asamoah, A. (eds.). 2003. Biodiversity<br />

Management Plan for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s.<br />

<strong>Forest</strong>ry Commission. Accra.<br />

Hall, J. B., and Swaine, M. D. 1981. Distribution and Ecology<br />

<strong>of</strong> Vascular Plants in a Tropical Rain <strong>Forest</strong> - <strong>Forest</strong><br />

Vegetation in <strong>Ghana</strong>. Dr W. Junk Publishers. The<br />

Hague, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. xv+382 pp.<br />

Hawthorne, W.D. 1998. <strong>Atewa</strong> and associated Upland Evergreen<br />

forests. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> recent data, and recommendations<br />

for a forthcoming management plan Report for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> Lands and <strong>Forest</strong>ry / biodiversity unit.<br />

IUCN. 2007. IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened Species.<br />

www.iucnredlist.org.<br />

Larsen, T. B. 2006. The <strong>Ghana</strong> Butterfly Fauna and its<br />

Contribution to <strong>the</strong> Objectives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Protected Areas<br />

System. WDSP Report no. 63. Wildlife Division<br />

(<strong>Forest</strong>ry Commission) & IUCN (World Conservation<br />

Union). 207 pp.<br />

Species recorded at <strong>the</strong> three RAP sites<br />

All RAP sites in this <strong>survey</strong> Atiwiredu Asiakwa South Asiakwa North<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> species recorded 839 295* 435* 307*<br />

Species <strong>of</strong> conservation concern** 36 20 13 14<br />

New species discovered 9*** 4 6 4<br />

New records for <strong>Ghana</strong> 46 16 28 24<br />

*excludes <strong>birds</strong>, fishes and dragonflies which were not sampled by site<br />

**species <strong>of</strong> global conservation concern as listed by IUCN (2007) and <strong>of</strong> national conservation concern (Schedule I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> Wildlife<br />

Conservation Regulation and black star species)<br />

***includes a new species <strong>of</strong> spider tick (see ‘o<strong>the</strong>r invertebrates’ in Executive Summary)<br />

11

Report at a Glance<br />

Results by Taxonomic Group<br />

Total species<br />

recorded<br />

Plants 314<br />

Species new<br />

to science<br />

New records for<br />

<strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Species <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

concern*<br />

6<br />

(Black Star)<br />

Species endemic to Upper<br />

Guinea<br />

Odonata 72 8 1 n.r.<br />

Butterflies 143 16<br />

Orthoptera (katydids) 61 8 36 n.r.<br />

Fishes 19 1 n.r.<br />

Amphibians 32 9 16<br />

Birds 155 1 6<br />

11 from Upper Guinea<br />

Endemic Bird Area<br />

Small mammals 15 2 2 3<br />

Large mammals 22 10 n.r.<br />

Primates 6 2 1<br />

*see Executive Summary for list <strong>of</strong> species<br />

n.r. = not reported by RAP scientists<br />

n.r.<br />

12 <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Executive Summary<br />

Introduction<br />

Across West Africa, forest cover has been reduced to less than 30% <strong>of</strong> its potential extent (Bakarr<br />

2001). The highly fragmented forest patches that remain continue to be degraded or completely<br />

lost at an alarming rate. Based on high levels <strong>of</strong> species endemism, coupled with intense<br />

and ongoing threats to <strong>the</strong>ir survival, <strong>the</strong> remaining West African forests have been designated<br />

as one <strong>of</strong> 34 global hotspots <strong>of</strong> biodiversity (Mittermeier et al. 2004).<br />

Montane habitats are extremely restricted in extent within this region. Long-term geological<br />

erosion has turned West Africa into a mostly flat landscape with significant tracts <strong>of</strong><br />

montane forest limited to <strong>the</strong> Upper Guinea Highlands. These montane forest areas constitute<br />

unique ecosystems with exceptional species richness and high levels <strong>of</strong> endemism (Bakarr et al.<br />

2001, 2004). Between <strong>the</strong> Upper Guinea and Cameroon Highlands, only <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> in<br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Volta Highlands between <strong>Ghana</strong> and Togo, and <strong>the</strong> Jos Plateau in Nigeria harbor<br />

significant upland forest patches. Among <strong>the</strong>se three, Upland Evergreen <strong>Forest</strong> is found only<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong>. The <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> (hereafter referred to as ‘<strong>Atewa</strong>’) is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> only two forest reserves in <strong>Ghana</strong> where Upland Evergreen <strong>Forest</strong> occurs (Hall and Swaine<br />

1981, Abu-Juam et al. 2003), <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r being <strong>the</strong> Tano Ofin <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, which is already<br />

highly degraded.<br />

<strong>Ghana</strong> has lost roughly 80% <strong>of</strong> its forest habitat since <strong>the</strong> 1920s (Cleaver 1992) and <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

represents one-third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remaining closed forest in <strong>the</strong> Eastern Region <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> (Mayaux<br />

et al. 2004, Chapter 11). <strong>Atewa</strong> is known to hold numerous endemic and rare species, in part<br />

due to <strong>the</strong> unique floristic composition <strong>of</strong> its Upland Evergreen forest generated by <strong>the</strong> misty<br />

conditions on top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateaus (Swaine and Hall 1977). In addition, several butterfly species<br />

are strictly endemic to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> (Larsen 2006). Seasonal marshy grasslands, swamps<br />

and thickets on <strong>the</strong> tops <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong>’s plateaus are also thought to be nationally unique (Hall and<br />

Swaine 1981).<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> has been <strong>of</strong>ficially classified in various ways over <strong>the</strong> past 90 years, with changes due<br />

mainly to new programs and designations assigned by <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> and not to<br />

any changes in <strong>Atewa</strong>’s biodiversity or ecological values. <strong>Atewa</strong> was declared a national forest<br />

reserve in 1925, <strong>the</strong>n was classified as a Special Biological Protection Area in 1994, as a Hill<br />

Sanctuary in 1995 and, finally in 1999, as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>’s 30 Globally Significant Biodiversity<br />

Areas (GSBAs) (Abu-Juam et al. 2003) based on its high botanical diversity. Designation as a<br />

GSBA is equivalent to IUCN’s Category IV designation: a protected area designated mainly for<br />

conservation through management intervention (IUCN 1994). In 2001, <strong>Atewa</strong> was listed as an<br />

Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International, one <strong>of</strong> 36 such areas in <strong>Ghana</strong> (Ntiamoa-<br />

Baidu et al. 2001).<br />

Historically, <strong>Atewa</strong> has been recognized as a nationally important reserve because <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> provides <strong>the</strong> headwaters <strong>of</strong> three river systems, <strong>the</strong> Ayensu River, <strong>the</strong> Densu<br />

River and <strong>the</strong> Birim River. These three rivers are <strong>the</strong> most important source <strong>of</strong> domestic and<br />

industrial water for local communities as well as for many <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>’s major population centers,<br />

including Accra. Thus, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> forests protect and provide a clean water source for much <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>’s human population and for key elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s biodiversity.<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

13

Scope <strong>of</strong> Project<br />

In addition to high biodiversity, <strong>Atewa</strong> is known to harbor<br />

mineralogical wealth including both gold and bauxite deposits.<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> opened several forest reserves<br />

for mining in 2001, but <strong>Atewa</strong> was not included. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Government granted an exploration license to ALCOA<br />

to prospect for bauxite deposits in <strong>Atewa</strong>.<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>Atewa</strong> had been classified as a<br />

Globally Significant Biodiversity Area (GSBA), ALCOA<br />

entered into an agreement with Conservation International<br />

(CI) to assist <strong>the</strong>m in better understanding <strong>the</strong> biodiversity<br />

context <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> in order to incorporate biodiversity into<br />

<strong>the</strong> company’s risk assessment and Environmental Impact<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project, should it proceed. This partnership<br />

involved applying CI’s Initial Biodiversity Assessment<br />

and Planning (IBAP) methodology to increase understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> an area’s ecosystems and socio-economic dynamics<br />

and to provide recommendations for incorporating biodiversity<br />

considerations in <strong>the</strong> earliest stages <strong>of</strong> decision-making.<br />

This partnership was formed in <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> providing<br />

significant gains for biodiversity conservation and industry,<br />

as well as for <strong>the</strong> government and people <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>.<br />

Previously, ALCOA and CI had partnered successfully<br />

to utilize <strong>the</strong> IBAP methodology and conduct biodiversity<br />

<strong>survey</strong>s in Guinea (West Africa) and Suriname (South<br />

America). For <strong>Atewa</strong>, CI first worked with partners to conduct<br />

desktop and preliminary field research on <strong>Atewa</strong>’s biodiversity<br />

in 2005, followed by a <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program<br />

(RAP) <strong>survey</strong> in June 2006 to assess a wide range <strong>of</strong> taxa, as<br />

well as potential threats to and opportunities for conservation<br />

in <strong>Atewa</strong>. Following <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong>, a consultative<br />

workshop was held at <strong>the</strong> Palace <strong>of</strong> Paramount Chief Okyehene<br />

in Kibi on June 26, 2006 with participation from local<br />

community members and Chiefs, representatives from AL-<br />

COA and several NGOs, and several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP scientists<br />

(see Appendix 11 for complete list <strong>of</strong> participants).<br />

RAP Expedition Overview and Objectives<br />

Conservation International’s <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program<br />

(RAP), a department within <strong>the</strong> Center for Applied Biodiversity<br />

Science (CABS), was founded in 1990 in response<br />

to <strong>the</strong> increasing loss <strong>of</strong> biodiversity in tropical ecosystems.<br />

RAP is an innovative biological inventory program designed<br />

to generate scientific information to catalyze conservation<br />

action in tropical areas that are under imminent threat <strong>of</strong><br />

habitat conversion.<br />

Toge<strong>the</strong>r with CI’s <strong>Ghana</strong> program and Center for Environmental<br />

Leadership in Business (CELB), RAP organized<br />

a rapid biological <strong>survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> in June 2006. Prior to <strong>the</strong><br />

RAP <strong>survey</strong>, most biological research had focused on plants<br />

and butterflies, with little data available for o<strong>the</strong>r taxonomic<br />

groups. The primary objective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> was to<br />

collect scientific data on <strong>the</strong> diversity and status <strong>of</strong> species<br />

within <strong>Atewa</strong> in order to make recommendations regarding<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir conservation and management. The specific aims <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

expedition were to:<br />

• Derive a brief but thorough overview <strong>of</strong> species diversity<br />

within <strong>Atewa</strong> and evaluate <strong>the</strong> area’s relative conservation<br />

importance;<br />

• Undertake an evaluation <strong>of</strong> threats to this biodiversity;<br />

• Provide management and research recommendations for<br />

this area toge<strong>the</strong>r with conservation priorities; and<br />

• Make RAP data publicly available for decision-makers<br />

as well as members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> general public in <strong>Ghana</strong> and<br />

elsewhere, with a view to increasing awareness <strong>of</strong> this<br />

ecosystem and promoting its conservation.<br />

RAP Criteria<br />

Criteria generally considered during RAP <strong>survey</strong>s in order<br />

to identify priority areas for conservation across taxonomic<br />

groups include species richness, species endemism, rare, new<br />

to science, and/or threatened species, and critical habitats.<br />

Measurements <strong>of</strong> species richness can be used to compare<br />

<strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species per area among areas within a given<br />

region. Measurements <strong>of</strong> species endemism indicate <strong>the</strong><br />

number <strong>of</strong> species endemic to some defined area and give<br />

an indication <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> uniqueness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area and <strong>the</strong><br />

species that will be threatened by degradation or loss <strong>of</strong> that<br />

area’s habitats (or conversely, <strong>the</strong> species that will likely be<br />

conserved through protected areas). Describing <strong>the</strong> number<br />

<strong>of</strong> critical habitats or sub-habitats within an area identifies<br />

sparse or poorly known habitats within a region that contribute<br />

to habitat variety and, <strong>the</strong>refore, to species diversity.<br />

RAP scientists use <strong>the</strong> IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened<br />

Species (IUCN 2007) to determine if species are globally<br />

threatened. Categories, from most to least threatened include:<br />

Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable<br />

(VU), Near Threatened (NT), Least Concern (LC).<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> rare and/or threatened species that are known<br />

or suspected to occur within a given area provides an indicator<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area for <strong>the</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity. The presence or absence <strong>of</strong> such species also aids<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir conservation status. Many species on <strong>the</strong><br />

IUCN Red List carry increased legal protection, thus giving<br />

greater importance and weight to conservation decisions.<br />

RAP Team and Focal Taxonomic Groups<br />

The RAP <strong>survey</strong>’s 20-member, multi-disciplinary team<br />

included representatives from <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Forest</strong>ry Commission, Water Research Institute, <strong>the</strong> Faculty<br />

<strong>of</strong> Renewable Natural Resources, <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kwame Nkrumah University <strong>of</strong> Science and Technology,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Forest</strong>ry Research Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>, l’Université<br />

d’Abobo-Adjamé (Côte d’Ivoire), University <strong>of</strong> Liège (Bel-<br />

14 <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

gium), University <strong>of</strong> Ulm (Germany), Natuurhistorisch<br />

Museum Naturalis (Leiden, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands), and Harvard<br />

University (USA).<br />

The RAP team, comprising experts specializing in West<br />

Africa’s ecosystems and biodiversity, examined selected taxonomic<br />

groups to determine <strong>the</strong> area’s biological diversity, its<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> endemism, and <strong>the</strong> uniqueness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ecosystem.<br />

RAP expeditions <strong>survey</strong> focal taxonomic groups as well as<br />

indicator species, with <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> choosing taxa whose presence<br />

can help identify a habitat type and its condition.<br />

At <strong>Atewa</strong>, <strong>the</strong> RAP team <strong>survey</strong>ed plants, Odonata<br />

(dragonflies and damselflies), Orthoptera (katydids), butterflies,<br />

fish, amphibians, <strong>birds</strong>, and mammals (including three<br />

mammal <strong>survey</strong> teams: small mammals, large mammals and<br />

primates).<br />

Study Area<br />

Surveys <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 23,665 ha <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> were<br />

conducted over 19 days (6 - 24 June 2006) at <strong>the</strong> beginning<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rainy season. Each RAP site ranged from lowland and<br />

some gallery forest down in <strong>the</strong> valleys to highland forest<br />

in <strong>the</strong> upper elevation as a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau formations.<br />

The mountain range, which peaks at 842 m a.s.l. (SRTM90<br />

data), runs roughly from north to south and is characterized<br />

by plateaus, which are remnants <strong>of</strong> a Tertiary peneplain. In<br />

addition to <strong>the</strong> three sites described below, <strong>the</strong> fish and dragonfly<br />

teams sampled streams and rivers (namely <strong>the</strong> Birim,<br />

Densu and Ayensu) and associated standing water habitats,<br />

with headwaters located within <strong>the</strong> reserve, as well as freshwater<br />

sites outside <strong>the</strong> reserve.<br />

<strong>Atewa</strong> lies within two climatic zones: <strong>the</strong> dry and <strong>the</strong><br />

wet semi-equatorial transition zone. The larger, nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> lies in <strong>the</strong> wet semi-equatorial climatic<br />

zone, which is characterized by high temperatures and a<br />

double maxima rainfall regime. It has a mean monthly temperature<br />

<strong>of</strong> between 24 and 29°C, and experiences a mean<br />

annual rainfall <strong>of</strong> between 120 and 1600 mm. The first rainfall<br />

peak occurs in May-July with <strong>the</strong> second one occurring<br />

in September-November.<br />

The area also lies in two vegetation zones. The transitional<br />

climatic zone and <strong>the</strong> thicket vegetation is <strong>the</strong> result<br />

<strong>of</strong> human activities in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> land cultivation, logging,<br />

and extraction <strong>of</strong> fuel wood. The vegetation cover<br />

also includes elephant grass, and <strong>the</strong> invasive “Siam weed”<br />

or “Acheampong weed” (Chromolaena odorata). North <strong>of</strong><br />

this zone, and covering about 80% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Akyem Abuakwa<br />

area is a moist deciduous forest. Unlike <strong>the</strong> evergreen forest,<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trees in <strong>the</strong> moist deciduous zone shed <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

leaves during various periods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> year. However, trees <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> lower layer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> zone remain evergreen throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

year. About 17,400 ha <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve is Upland Evergreen<br />

forest. <strong>Atewa</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> only two forest reserves in <strong>the</strong> country<br />

in which this forest-type occurs, <strong>the</strong> second one being Tano<br />

Ofin, and <strong>the</strong>se two reserves toge<strong>the</strong>r hold approximately<br />

95% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upland Evergreen forest in <strong>the</strong> country. The<br />

diverse flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> contains submontane elements, with<br />

characteristic herbaceous species, and abundant and diverse<br />

epiphytic and terrestrial ferns; a number <strong>of</strong> plant species<br />

found here are not known to occur elsewhere in <strong>Ghana</strong>. The<br />

bowals (seasonal marshy grasslands on bauxite outcrops),<br />

swamps and thickets that occur here are also thought to be<br />

nationally unique.<br />

Overall, <strong>Atewa</strong> is considered to have a forest condition<br />

score <strong>of</strong> 3 (on a scale <strong>of</strong> 1-6), which indicates that it is<br />

slightly degraded but has predominantly good forest with<br />

healthy and abundant regeneration <strong>of</strong> timber trees and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

forest plants (Hawthorne and Abu-Juam 1995).<br />

RAP camps were established at three sites within <strong>Atewa</strong>.<br />

The RAP sites were chosen to coincide with areas <strong>of</strong> high<br />

biodiversity and concentrated bauxite deposits (Atiwiredu,<br />

Asiakwa South and Asiakwa North) that had been earmarked<br />

for exploitation activities by ALCOA. The most<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> was not <strong>survey</strong>ed because it is fairly<br />

degraded and was not a focus <strong>of</strong> ALCOA’s activities at <strong>the</strong><br />

time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong>.<br />

Site 1 (Atiwiredu) was located at 6°12’24.7’’N,<br />

0°34’37.2’’W, at an elevation 795 m, and sampling was conducted<br />

here from 6 – 10 June, 2006. This site had an extensive<br />

network <strong>of</strong> roads, and was subject to prospecting activity<br />

by ALCOA. Despite this activity, <strong>the</strong> forest condition was<br />

rated as 2 by <strong>the</strong> botanical team, indicating a low level <strong>of</strong><br />

disturbance. Two plant species endemic to Upper Guinea,<br />

Neolemonniera clitandrifolia and Aframomum atewae, were<br />

present at <strong>the</strong> site, and <strong>the</strong> dominant trees were Cola boxiana<br />

and Chidlowia sanguinea. This site showed evidence <strong>of</strong> previous<br />

logging <strong>of</strong> economically important tree species. There<br />

were also indications <strong>of</strong> hunting (spent cartridges, snares,<br />

and hunting trails.)<br />

Site 2 (Asiakwa South) was situated at 6°15’44.3’’N,<br />

0°33’18.8’’W, at an elevation <strong>of</strong> 690 m, and sampling was<br />

conducted here from 11 – 16 June, 2006. This site, while<br />

not currently subject to prospecting activity, still contained<br />

an extensive network <strong>of</strong> roads from previous exploration activity,<br />

some overgrown with tall grasses. These roads appear<br />

to act as passages allowing <strong>the</strong> penetration <strong>of</strong> invasive elements,<br />

such as grasses or species <strong>of</strong> insects normally associated<br />

with open habitats, deep into <strong>the</strong> forest. The condition<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest at this site was rated as 3, and <strong>the</strong> dominant<br />

tree species were Rinorea oblogifolia and Hymenostegia afzelii.<br />

This site showed evidence <strong>of</strong> hunting (spent cartridges, wire<br />

snares) and harvesting <strong>of</strong> chewing stick, sponge and cane.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong>re were no signs <strong>of</strong> previous farming activities.<br />

Site 3 (Asiakwa North) was located at 6°16’16.4’’N,<br />

0°33’52.8’’W, elevation 769 m, and was sampled from 16 –<br />

24 June, 2006. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> site was covered with tall, closedcanopy<br />

forest, with little underbrush and no open roads. Its<br />

condition was rated as 2, and <strong>the</strong> dominant tree species was<br />

Rinorea oblongifolia. There were few gaps in <strong>the</strong> forest, which<br />

A <strong>Rapid</strong> Biological Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>, Eastern <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

15

Executive Summary<br />

accounts for <strong>the</strong> low number <strong>of</strong> species associated with such<br />

habitats. The only gaps present were overgrown with tall,<br />

broad-leaved plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family Marantaceae. Of <strong>the</strong> three<br />

sites sampled, this site showed <strong>the</strong> most extensive evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

hunting, with hundreds <strong>of</strong> spent cartridges, wire snares, and<br />

an extensive network <strong>of</strong> hunting trails.<br />

RAP Results<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> this RAP <strong>survey</strong> confirm that <strong>Atewa</strong> is a site<br />

<strong>of</strong> extremely high importance for global biodiversity conservation<br />

and should be protected in its entirety. This forest<br />

reserve represents <strong>the</strong> last intact piece <strong>of</strong> Upland Evergreen<br />

forest in <strong>Ghana</strong> and is a critical source <strong>of</strong> clean water for <strong>the</strong><br />

local people and many <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>’s human population cen-<br />

Table 1. Species <strong>of</strong> conservation concern recorded in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> <strong>Range</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> during <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong>.<br />

Taxon Species name Common name Threat status*<br />

Sites<br />

Atiwiredu Asiakwa S Asiakwa N<br />

Amphibian Conraua derooi CR x x<br />

Amphibian Hyperolius bobirensis EN x x<br />

Amphibian Phrynobatrachus ghanensis EN x<br />

Plant Neolemonniera clitandrifolia EN / Black star x<br />

Amphibian Kassina arboricola VU x x<br />

Bird Bleda eximius Green-tailed Bristlebill VU<br />

Bird Criniger olivaceus Yellow-bearded Greenbul VU<br />

Bird Melaenornis annamarulae Nimba Flycatcher VU<br />

Primate Colobus vellerosus Ge<strong>of</strong>froy’s pied colobus VU x x x<br />

Plant Sapium aubrevillei VU / Black star x<br />

Amphibian Amietophrynus togoensis NT x<br />

Amphibian Acanthixalus sonjae NT x<br />

Amphibian Afrixalus nigeriensis NT x x<br />

Amphibian Afrixalus vibekensis NT x<br />

Amphibian Phrynobatrachus alleni NT x<br />

Bird Bycanistes cylindricus Brown-cheeked Hornbill NT<br />

Bird Illadopsis rufescens Rufous-winged Illadopsis NT<br />

Bird Lamprotornis cupreocauda Copper-tailed Glossy Starling NT<br />

L. Mammal Anomalurus pelii Pel’s flying squirrel NT x<br />

Sm. Mammal Crocidura grandiceps Large-headed shrew NT x<br />

Sm. Mammal Scotonycteris zenkeri Zenker’s Fruit Bat NT x x<br />

L. Mammal Cephalophus dorsalis Bay Duiker LR/nt x x x<br />

L. Mammal Cephalophus maxwelli Maxwell’s Duiker LR/nt x x x<br />

L. Mammal Cephalophus niger Black Duiker LR/nt x<br />

L. Mammal Cephalophus silvicultor Yellow-backed Duiker LR/nt / Sch. I x<br />

L. Mammal Neotragus pygmaeus Royal Antelope LR/nt x x x<br />

Primate Procolobus verus Olive colobus LR/nt x<br />

L. Mammal Epixerus ebii Western palm squirrel DD x x<br />

Odonate Atoconeura luxata VU in WA<br />

L. Mammal Civettictis civetta African Civet Sch. I x x<br />

L. Mammal Nandinia binotata African Palm Civet Sch. I x x<br />

L. Mammal Uromanis tetradactyla Long-tailed Pangolin Sch. I x<br />

Plant Gilbertiodendron splendidum Black star x x<br />

Plant Ixoria tenuis Black star x x<br />

Plant Psychotria longituba Black star x<br />

Plant Psychotria subglabra Black star x<br />

Sm. Mammal Hypsugo [crassulus] bellieri Bellier’s Broad-headed Pipistrelle n.a. x x<br />

Sm. Mammal Pipistrellus aff. grandidieri Grandidier’s Pipistrelle n.a. x<br />

* Threat status:<br />

IUCN Red List categories: Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), Near Threatened (NT), Lower Risk/near threatened (LR/nt),<br />

Data Deficient (DD) (IUCN 2007)<br />

Sch. I Species wholly protected in <strong>Ghana</strong> and listed on Schedule I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong> Wildlife Conservation Regulation<br />

Black star Species ranked as internationally rare and uncommon in <strong>Ghana</strong> (Hawthorne and Abu-Juam 1995)<br />

n.a. Not assessed by <strong>the</strong> last IUCN revision due to recent taxonomic results, but when assessed it will be added to IUCN Red List<br />

VU in WA Listed by IUCN as regionally vulnerable for western Africa<br />

16 <strong>Rapid</strong> Assessment Program

Executive Summary<br />

ters, including Accra. Our results show that <strong>Atewa</strong> is still a<br />

uniquely important site that continues to harbor a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> rare and threatened species within an intact and unique<br />

habitat type (Table 1).<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RAP <strong>survey</strong> not only corroborate<br />

previous designations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong> as an important site for<br />

biodiversity conservation (see below), but strongly suggest<br />

that <strong>the</strong> biological community present at <strong>Atewa</strong> represents a<br />

very rare example <strong>of</strong> a relatively intact West African forest, a<br />

highly unusual and (from a conservation perspective) highly<br />

significant finding. All taxonomic groups <strong>survey</strong>ed were<br />

found to include unique species assemblages that are representative<br />

<strong>of</strong> Upper Guinean rainforest fauna. <strong>Atewa</strong> harbors<br />

a high and unique diversity <strong>of</strong> dragonflies and butterflies, as<br />

well as primates that are highly threatened throughout West<br />

Africa (Table 2).<br />

The RAP results add to previous biological data in<br />

several ways, most notably by showing that <strong>Atewa</strong> is an<br />

important site for amphibians. An extremely high proportion<br />

<strong>of</strong> threatened amphibian species were recorded (almost<br />

one-third <strong>of</strong> recorded species are Red-Listed), including <strong>the</strong><br />

Critically Endangered Conraua derooi, for which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Atewa</strong><br />

<strong>Range</strong> is likely to hold <strong>the</strong> largest remaining populations.<br />

While this species is historically known from a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> sites close to <strong>the</strong> Togolese border, recent <strong>survey</strong>s have<br />

recorded it only from some <strong>of</strong> its previously known localities,<br />

where it is under extreme pressure from habitat destruction<br />

and consumption. Hence, <strong>Atewa</strong> could hold <strong>the</strong> last<br />