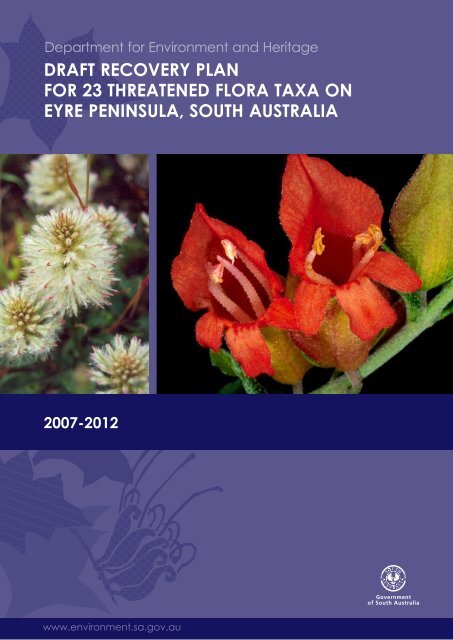

Draft Recovery Plan for threatened flora on Eyre Peninsula 2007

Draft Recovery Plan for threatened flora on Eyre Peninsula 2007

Draft Recovery Plan for threatened flora on Eyre Peninsula 2007

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Table 1. <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species addressed within this recovery plan: level of endemism,c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status, priority category and target c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status within 5 yearsEndangeredEPBC ActVulnerableEPBC ActThreatenedwattlesChalky Wattle (Acacia cretacea)Whibley Wattle (Acacia whibleyana)Fat-leaved Wattle (Acacia pinguifolia)Jumping-jack Wattle (Acaciaenterocarpa)P1P1P1P1Resin Wattle (Acacia rhetinocarpa) P2Threatenedorchids^ Mt Olinthus Greenhood (Pterostylis‘Mt Olinthus’ )Metallic Sun-orchid (Thelymitraepipactoides)P3P1Nodding Rufous-hood (Pterostylis aff.despectans)Winter Spider-orchid (Caladeniabrumalis)Desert Greenhood (Pterostylisxerophila)P2P1P2Threatenedannuals-Annual Candles (Stackhousia annua)Silver Candles (Pleuropappusphyllocalymmeus)P2P3Prickly Raspwort (Haloragis eyreana) P2 West Coast Mintbush (Prostantheracalycina)P2Other <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species(perennials)Tufted Bush-pea (Pultenaeatrichophylla)Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla (Ptilotusbeckerianus)Silver Daisy-bush (Olearia pannosa ssp.pannosa)Bead Samphire (Halosarciaflabelli<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mis)^ Sandalwood (Santalum spicatum)Club Spear-grass (Austrostipanullanulla)Granite Mudwort (Limosella granitica)Microlepidium alatumYellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea (Swains<strong>on</strong>apyrophila)P2P1P1P2P2P3P3P3P3Key Bold and black text = Endemic to <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> Grey text = Known populati<strong>on</strong>s in other Australian statesBlack text = Endemic to South Australia ^ = Only listed under the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 = Aim to maintain and stabilise species populati<strong>on</strong> over 5 years = Aim to down-list species <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> status within 5 yearsP1 = Priority 1 species P2 = Priority 2 species P3 = Priority 3 species2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

CostsA minimum financial investment of approximately $ 154 000 <strong>on</strong> average per year <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>5 years is required to implement the plan’s Core per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria, which focusprimarily <strong>on</strong> Priority 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species. To fund the entire recovery plan, a financialinvestment of approximately $ 300 000 per year <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 years will start meeting thec<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> needs of all <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa and cricital habitat identified within thisplan.Wider benefitsImplementati<strong>on</strong> of this plan c<strong>on</strong>tributes to holistic natural resource management goals,including habitat protecti<strong>on</strong> and management, linking fragmented habitats, strategicthreat abatement, and community engagement in regi<strong>on</strong>al biodiversity and c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>issues. Anticipated broader ecological benefits of the plan include:• maintenance of habitat integrity that facilitates ecosystem adaptati<strong>on</strong> to climatechange• protecti<strong>on</strong> of water dependent ecosystems, such as wetlands and riparian areas,within <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species critical habitat• an improved understanding of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> and insect/pollinati<strong>on</strong> processes• an improved understanding of soil biota functi<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant habitats.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 3

9.7 Main references ...........................................................................................................6810 Whibley Wattle Acacia whibleyana RS Cowan & Maslin...............................................6910.1 Status .............................................................................................................................6910.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>.....................................................................................................................6910.3 Habitat critical to survival............................................................................................6910.4 Biology and ecology ...................................................................................................7310.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ..................................................................................7410.6 Threats to Whibley Wattle and associated recovery goals ....................................7510.7 Main references ...........................................................................................................7811 Winter Spider-orchid Caladenia brumalis syn. Arachnorchis brumalis DL J<strong>on</strong>es .......7911.1 Status .............................................................................................................................7911.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>.....................................................................................................................7911.3 Habitat critical to survival............................................................................................7911.4 Biology and ecology ...................................................................................................8211.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ..................................................................................8311.6 Threats to Winter Spider-orchid and associated recovery goals ...........................8311.7 Main references ...........................................................................................................8512 Club Spear-grass Austrostipa nullanulla J Everett and SWL Jacobs .............................8612.1 Status .............................................................................................................................8612.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>.....................................................................................................................8612.3 Habitat critical to survival............................................................................................8612.4 Biology and ecology ...................................................................................................8912.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ..................................................................................8912.6 Threats to Club Spear-grass and associated recovery goals .................................8912.7 Main references ...........................................................................................................9113 Prickly Raspwort Haloragis eyreana Orchard .................................................................9213.1 Status .............................................................................................................................9213.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>.....................................................................................................................9213.3 Habitat critical to survival............................................................................................9213.4 Biology and ecology ...................................................................................................9413.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ..................................................................................9513.6 Threats to Prickly Raspwort and associated recovery goals...................................9613.7 Main references ...........................................................................................................9814 Bead Samphire Halosarcia flabelli<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mis PG Wils<strong>on</strong>.......................................................9914.1 Status .............................................................................................................................9914.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>.....................................................................................................................9914.3 Habitat critical to survival............................................................................................9914.4 Biology and ecology .................................................................................................10114.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ................................................................................10214.6 Threats to Bead Samphire and associated recovery goals..................................10214.7 Main references .........................................................................................................10415 Granite Mudwort Limosella granitica WR Barker...........................................................10515.1 Status ...........................................................................................................................10515.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>...................................................................................................................10515.3 Habitat critical to survival..........................................................................................10515.4 Biology and ecology .................................................................................................10715.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ................................................................................10715.6 Threats to Granite Mudwort and associated recovery goals...............................10815.7 Main reference...........................................................................................................10916 Microlepidium alatum JM Black; EA Shaw ....................................................................11016.1 Status ...........................................................................................................................11016.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong>...................................................................................................................11016.3 Habitat critical to survival..........................................................................................11016.4 Biology and ecology .................................................................................................11216.5 Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s ................................................................................11316.6 Threats to Microlepidium alatum and associated recovery goals ......................11316.7 Main reference...........................................................................................................11517 Silver Daisy-bush Olearia pannosa ssp. pannosa I Hook ............................................116<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 5

TablesTable 1. <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species addressed within this recovery plan: levelof endemism, c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status, priority category and target c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>status within 5 years ...................................................................................................2Table 1.1. Status of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species covered within this plan .................................13Table 1.2. Species and percentage of their populati<strong>on</strong> within <strong>Eyre</strong> Hills IBRA Subregi<strong>on</strong>.....16Table 1.3. Current and potential regi<strong>on</strong>al, state and nati<strong>on</strong>al stakeholders involved in themanagement of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ..........................18Table 3.1. Summary of direct threats to <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> and asummary of recommended acti<strong>on</strong>s .....................................................................26Table 3.2. Summary of impediments to <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> and asummary of recommended acti<strong>on</strong>s .....................................................................27Table 5.1. Risk matrix table used throughout plan to analyse threat severity to individualspecies ......................................................................................................................37Table 6.1. Chalky Wattle vital attributes .....................................................................................39Table 6.2. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Chalky Wattle...................................43Table 6.3. Key threats to Chalky Wattle and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria44Table 7.1. Jumping-jack Wattle vital attributes..........................................................................46Table 7.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of northern <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> Jumping-jack Wattle subpopulati<strong>on</strong>s...............................................................................................................48Table 7.3. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of southern Jumping-jack Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s .......49Table 7.4. Jumping-jack Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ....................49Table 7.5. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Jumping-jack Wattle .......................51Table 7.6. Key threats to Jumping-jack Wattle and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .......................................................................................................................52Table 8.1. Fat-leaved Wattle vital attributes ..............................................................................54Table 8.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of northern Fat-leaved Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s ............56Table 8.3. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of southern Fat-leaved Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s............57Table 8.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Fat-leaved Wattle............................59Table 8.5. Key threats to Fat-leaved Wattle and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .......................................................................................................................60Table 9.1. Resin Wattle vital attributes ........................................................................................62Table 9.2. Resin Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ...................................64Table 9.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Resin Wattle ......................................66Table 9.4. Key threats to Resin Wattle and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria ..67Table 10.1. Whibley Wattle vital attributes .................................................................................69Table 10.2. Important Whibley Wattle sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s ............................................................73Table 10.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Whibley Wattle ...............................74Table 10.4. Key threats to Whibley Wattle and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria...................................................................................................................................76Table 11.1. Winter Spider-orchid vital attributes ........................................................................79Table 11.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of selected Winter Spider-orchid sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s......81Table 11.3. Winter Spider-orchid sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ...................81Table 11.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Winter Spider-orchid ......................83Table 11.5. Key threats to Winter Spider-orchid and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .......................................................................................................................84Table 12.1. Club Spear-grass vital attributes ..............................................................................86<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 9

Table 12.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of Club Spear-grass sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s............................88Table 12.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Club Spear-grass............................89Table 12.4. Key threats to Club Spear-grass and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .......................................................................................................................90Table 13.1. Prickly Raspwort vital attributes................................................................................92Table 13.2. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Prickly Raspwort .............................95Table 13.3. Key threats to Prickly Raspwort and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .......................................................................................................................97Table 14.1. Bead Samphire vital attributes.................................................................................99Table 14.2. Examples of niche sharing species, soil descripti<strong>on</strong> and associated edgevegetati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Bead Samphire.............................................................................101Table 14.3. Bead Samphire sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>..........................101Table 14.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Bead Samphire ............................102Table 14.5. Key threats to Bead Samphire and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................103Table 15.1. Granite Mudwort vital attributes............................................................................105Table 15.2. Granite Mudwort sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>.......................107Table 15.3. Key threats to Granite Mudwort and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................108Table 16.1. Microlepidium alatum vital attributes ...................................................................110Table 16.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Microlepidium alatum............................................112Table 16.3. Microlepidium alatum sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ..............112Table 16.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Microlepidium alatum .................113Table 16.5. Key threats to Microlepidium alatum and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................114Table 17.1. Silver Daisy-bush vital attributes .............................................................................116Table 17.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of northern Silver Daisy-bush sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s ...........118Table 17.3. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of southern Silver Daisy-bush sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s...........119Table 17.4. Silver Daisy-bush sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ........................119Table 17.5. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Silver Daisy-bush ...........................121Table 17.6. Key threats to Silver Daisy-bush and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................122Table 18.1. Nodding Rufous-hood vital attributes ...................................................................124Table 18.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Nodding Rufous-hood sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><strong>Peninsula</strong>.................................................................................................................126Table 18.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Nodding Rufous-hood.................126Table 18.4. Key threats to Nodding Rufous-hood and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................127Table 19.1. Mount Olinthus Greenhood vital attributes ..........................................................129Table 19.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Mount Olinthus Greenhood sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong><strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ........................................................................................................131Table 19.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Mount Olinthus Greenhood........132Table 19.4. Key threats to Mount Olinthus Greenhood and summary of associatedper<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria .............................................................................................133Table 20.1. Silver Candles vital attributes..................................................................................134Table 20.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Silver Candles..........................................................136Table 20.3. Silver Candles sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ............................137Table 20.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Silver Candles ...............................13710 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

Table 20.5. Key threats to Silver Candles and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria.................................................................................................................................138Table 21.1. West Coast Mintbush vital attributes .....................................................................140Table 21.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s of West Coast Mintbush sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in the vicinityof Streaky Bay and Venus Bay .............................................................................142Table 21.3. West Coast Mintbush sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>................143Table 21.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve West Coast Mintbush...................144Table 21.5. Key threats to West Coast Mintbush and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................145Table 22.1. Desert Greenhood vital attributes .........................................................................147Table 22.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Desert Greenhood..................................................149Table 22.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Desert Greenhood.......................150Table 22.4. Key threats to Desert Greenhood and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................151Table 23.1. Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla vital attributes .....................................................................153Table 23.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s.................155Table 23.3. Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s within reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>.........156Table 23.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla ..................157Table 23.5. Key threats to Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................158Table 24.1. Tufted Bush-pea vital attributes..............................................................................160Table 24.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Tufted Bush-pea sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s .........................162Table 24.3. Important populati<strong>on</strong>s of Tufted Bush-pea...........................................................163Table 24.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Tufted Bush-pea ...........................164Table 24.5. Key threats to Tufted Bush-pea and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................165Table 25.1. Sandalwood vital attributes ...................................................................................167Table 25.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Sandalwood sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ....169Table 25.3. Sandalwood sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ..............................170Table 25.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Sandalwood.................................172Table 25.5. Key threats to Sandalwood and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria.................................................................................................................................173Table 26.1. Annual Candles vital attributes..............................................................................175Table 26.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Annual Candles <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> .......................177Table 26.3. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Annual Candles ...........................178Table 26.4. Key threats to Annual Candles and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................179Table 27.1. Yellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea vital attributes.....................................................................180Table 27.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Yellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea locati<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ..182Table 27.3. Yellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>................183Table 27.4. Key threats to Yellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................184Table 28.1. Metallic Sun-orchid vital attributes ........................................................................186Table 28.2. Vegetati<strong>on</strong> associated with Metallic Sun-orchids <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ................188Table 28.3. Metallic Sun-orchid sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s in reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> ...................189Table 28.4. Previous management acti<strong>on</strong>s to c<strong>on</strong>serve Metallic Sun-orchid ......................190Table 28.5. Key threats to Metallic Sun-orchid and summary of associated per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mancecriteria .....................................................................................................................191<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 11

Table 29.1. Prioritised <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species ......................................................................193Table 30.1. Summary of percentage of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s within <strong>Eyre</strong> Hills IBRASubregi<strong>on</strong>................................................................................................................194Table 30.2. Decisi<strong>on</strong> making table used to prioritise Focus Work Areas................................195Table 30.3. State <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> and fauna species within Priority 1A-D Focus Work Areas.................................................................................................................................195Table 31.1. Key to budget tables ..............................................................................................199Table 31.2. Timetable of recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s and per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria (Part 1of 3) ..............200Table 31.3. Break down of per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria and associated funding tier by species.203Table 31.4. Species by species breakdown of research per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria <strong>on</strong>ly ...........204Table 32.1. Examples of management practices that may c<strong>on</strong>tribute to the extent andimpact of identified threats and impediments to the recovery of nati<strong>on</strong>ally<str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> .......................................................205Table E1. Matrix of extent of current threats and impediments to recovery of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g>plant species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>…………………………………………………….. 230Table E2. Matrix of future threats and impediments to the recovery of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plantspecies <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> …………………………………………………………… 231Table E3. Criteria used to allocate threat scores <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> matrix of extent of current threats andimpediments to the recovery of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>(Table E1) .………………………………………………………………………………. 232Table E4. Criteria used to allocate threat scores <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> matrix of future threats andimpediments to the recovery of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>(Table E2) ……………………………………………………………………………….. 234Table F1. Percentage of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s within the <strong>Eyre</strong> Hills IBRASubregi<strong>on</strong>, SA ………………………………………………………………………..… 237Table I1. Suspected fire and disturbance dependant species .…………………………..… 245Table J1. Threatened <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s within NPWSA Reserves <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> …..… 24812 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

Table 1.2. Species and percentage of their populati<strong>on</strong> within <strong>Eyre</strong> Hills IBRA Subregi<strong>on</strong>Species% populati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>Eyre</strong> HillsIBRA Sub Regi<strong>on</strong> SASpecies% populati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>Eyre</strong> HillsIBRA Sub Regi<strong>on</strong> SASilver Daisy-bush 100 Jumping-jack Wattle 95Nodding Rufous-hood 100 Whibley Wattle 86Desert Greenhood 100 Metallic Sun-orchid 83Tufted Bush-pea 100 Winter Spider-orchid 65Annual Candles 100 Resin Wattle 50Mt Olinthus Greenhood 100 Silver Candles 34Fat-leaf Wattle 99 Bead Samphire 11Prickly Raspwort 99 Yellow Swains<strong>on</strong>-pea 11Chalky Wattle 97 West Coast Mintbush 10Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla 961.3 C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status and legislati<strong>on</strong>In Australia, species can be listed as <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> at a nati<strong>on</strong>al level, under theComm<strong>on</strong>wealth Government’s Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Protecti<strong>on</strong> and Biodiversity C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Act1999 (EPBC Act). All species listed under this Act are recognised as Matters of Nati<strong>on</strong>alEnvir<strong>on</strong>mental Significance (Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth of Australia 2006). Species can also be listedas <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> at a state level. In South Australia, state level <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> areprotected under the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (NPW Act) and listed inSchedules 7, 8 and 9.Species c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status is periodically reviewed. For example, at the time ofpublicati<strong>on</strong>, Senna Wattle (Acacia praemorsa) is being c<strong>on</strong>sidered <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> listing under theEPBC Act 1999 as nati<strong>on</strong>ally endangered. Similarly, Feathery Wattle (Acacia imbricata) isbeing c<strong>on</strong>sidered <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> down-listing, as a result of recommendati<strong>on</strong>s from local experts andextensive surveys completed under the interim recovery plan.Threatened plant species in this plan are assessed and reviewed against the WorldC<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Uni<strong>on</strong> criteria (IUCN) (Table 1.1). This is an important review process becauseit ensures internati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status classificati<strong>on</strong> standards are applied. Australianlegislati<strong>on</strong> bases its criteria <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> status <strong>on</strong> IUCN criteria. All acti<strong>on</strong>s andper<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria in this plan are structured to link back to IUCN criteria.Objectives of the Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Protecti<strong>on</strong> and Biodiversity C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Act 1999This plan has been developed in line with Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Protecti<strong>on</strong> and BiodiversityC<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Act 1999 objectives 1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.2.3 and 1.2.4.EPBC Act Objective 1.2.1: Promoting a cooperative approach to the protecti<strong>on</strong> andmanagement of the envir<strong>on</strong>ment involving governments, the community, land holdersand indigenous people.To be successful, this plan requires the community and stakeholders to adopt andimplement recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s, and complete a critical review to progress future work.There<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e, expected outcomes include involvement of stakeholders and promoti<strong>on</strong> ofcooperative natural resource management (Acti<strong>on</strong>s 2a – 2c).16 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

EPBC Act Objective 1.2.2: Assisting in the co-operative implementati<strong>on</strong> of Australia’senvir<strong>on</strong>mental resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities.This plan c<strong>on</strong>tains per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria that directly deliver and/or support envir<strong>on</strong>mentallegislati<strong>on</strong> and policy at nati<strong>on</strong>al, state and regi<strong>on</strong>al levels. This legislati<strong>on</strong> and policyincludes:• United Nati<strong>on</strong>s C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Biological Diversity (Internati<strong>on</strong>al)• C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora(Internati<strong>on</strong>al)• Nati<strong>on</strong>al Strategy <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> the C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> of Australia’s Biological Diversity (Nati<strong>on</strong>al)• Nati<strong>on</strong>al Biodiversity and Climate Change Acti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Nati<strong>on</strong>al)• South Australia’s Strategic <str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g> (State)• No Species Loss – A Nature C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Strategy <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> SA <strong>2007</strong>-2017 (State)• State Natural Resources Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2006 (State)• NatureLinks: East Meets West Corridor <str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Regi<strong>on</strong>al)• Initial Natural Resources Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> NaturalResources Management Regi<strong>on</strong> 2006-07 (Regi<strong>on</strong>al).EPBC Act Objectives 1.2.3 and 1.2.4: Recognising the role of indigenous people in thec<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> and ecologically sustainable use of Australia’s biodiversity and promotingthe use of indigenous peoples’ knowledge with the involvement of, and in co-operati<strong>on</strong>with, the owners of the knowledge.1.4 Internati<strong>on</strong>al obligati<strong>on</strong>sThe goals in this plan are c<strong>on</strong>sistent with Australia’s obligati<strong>on</strong>s under the C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>Biological Diversity, ratified by Australia in 1993, and the Nati<strong>on</strong>al Strategy <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> theC<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> of Australia’s Biological Diversity (1996).Although some species covered by this plan are known to occur within wetlands, therecovery acti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> these species will not impact <strong>on</strong> obligati<strong>on</strong>s made under theC<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Wetlands of Internati<strong>on</strong>al Importance (Ramsar C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> 1971).The Winter Spider-orchid (Caladenia brumalis syn. Arachnorchis brumalis), DesertGreenhood (Pterostylis xerophila), Nodding Rufous-hood (Pterostylis aff. despectans) andMetallic Sun-orchid (Thelymitra epipactoides) are listed under the C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>Internati<strong>on</strong>al Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1975) (CITES). Allcorresp<strong>on</strong>ding recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s in this plan are c<strong>on</strong>sidered within Australia's obligati<strong>on</strong>sunder CITES.1.5 Affected interestsThe successful implementati<strong>on</strong> of this plan will require that all stakeholders are identifiedand engaged in the implementati<strong>on</strong> of this plan. This plan is designed to link withcommunity groups, land managers and statutory organisati<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>nected with<str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> (Table 1.3).Private land holders, land developers, mining lease holders, SA Water, ETSA Utilities, LocalGovernment, the Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment and Heritage (DEH), and the Department<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Transport Energy and Infrastructure (DTEI) are all major stakeholders that directly own ormanage sites where these <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species are known to occur. When new subpopulati<strong>on</strong>sor populati<strong>on</strong>s are discovered, the relevant land managers will be c<strong>on</strong>sultedregarding recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> land <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> which they are resp<strong>on</strong>sible.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 17

(leaving staff distressed and in need of support),from armed robbery to customers having heartattacks. Through the EAP, the employer wasable to ensure that managers were sufficientlytrained to resp<strong>on</strong>d to such incidents and,where appropriate, encourage staff to accessthe EAP support services. This enabled themanagers to delegate support to those betterqualified to provide such help and left them toc<strong>on</strong>centrate <strong>on</strong> their core managing roles.How the service works:Service promoti<strong>on</strong>All staff receive a credit card-sized in<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong>card giving a service summary al<strong>on</strong>g with c<strong>on</strong>tactdetails. Posters are placed in every workplacelocati<strong>on</strong> (within sight of staff but not customers!)and these are replaced regularly, to keep theimages fresh and the message current. The EAPprovider provides both an intranet and a website<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Peters<strong>on</strong>s, with company-specific in<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong>.Staff are encouraged to view this regularly.On-site employee briefings are given by the EAPprovider and a DVD about the service is used at allstaff inducti<strong>on</strong> sessi<strong>on</strong>s. A briefing, specificallyaimed at managers, not <strong>on</strong>ly explains how theservice works but also helps them understand howthey can receive management support and howthey can help their staff access the service.C<strong>on</strong>fidentiality and feedback protocolEvidence has shown that staff access a servicemore freely when they believe that theirc<strong>on</strong>fidentiality is not compromised, yet theemployer who pays <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> the service understandablyexpects and needs feedback. ManagementIn<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> is agreed during the setting-up of thec<strong>on</strong>tract. In this case, Peters<strong>on</strong>s receive a quarterlyreport showing service usage across eight regi<strong>on</strong>sin the UK. They do not receive individual storefeedback, because fewer than 50 employees workin most of their stores and 50 is the minimum sizeof pooled data permitted by the EAP provider.The in<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> provides an analysis of thenumbers of people who accessed the service andthe issues they presented with. It identifies howmany progressed to face-to-face counselling andhow many sessi<strong>on</strong>s these people used. It alsohighlights any trends and patterns that may berelevant <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> the employer.Access and referral processStaff can access professi<strong>on</strong>al support and advicethrough the freeph<strong>on</strong>e teleph<strong>on</strong>e service run bythe EAP provider. Because this is available 24hours, staff can ph<strong>on</strong>e when it suits them.Employees self-refer to counselling with a range ofproblems, the most frequent of which could beclassified as relati<strong>on</strong>ship issues, encompassingeverything from the breakup of a marriage todifficulties with teenage offspring. These issueshave a real effect <strong>on</strong> people’s ability to focus atwork, yet the issues were not specifically workrelated. Prior to purchasing an EAP, Peters<strong>on</strong>s hadno resources to support staff in these areas.Measurement and evaluati<strong>on</strong>The Management In<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mati<strong>on</strong> provided to theemployer also analyses the workplace issues thatare impacting <strong>on</strong> staff. The EAP is able to showsome regi<strong>on</strong>al variati<strong>on</strong>, so that with somepresenting issues, such as ‘bullying’, theorganisati<strong>on</strong> can better direct training resources ortake appropriate remedial acti<strong>on</strong>. Another exampleof the positive use of this MI featured recent usagedata identifying staff affected by change - thestores were going through a major refit, and thisleft some staff feeling more vulnerable andanxious, <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> several reas<strong>on</strong>s, including greaterexposure to assault from customers. By sharingthis trend with the employer, the provider was ableto identify the support which staff needed andintroduce c<strong>on</strong>sultati<strong>on</strong> and training activities tohelp staff adjust to the changes. In this way,Peters<strong>on</strong>s finds that the counselling service not<strong>on</strong>ly meets the needs of individual employees butalso helps corporately - bringing value from theshop floor to the boardroom.Proven benefits to the organisati<strong>on</strong>After two years, the company feels that the EAPpurchase cost has been more than justified.Sickness absence has reduced and staff arestaying l<strong>on</strong>ger (when asked whether Peters<strong>on</strong>sis a good employer, more than 80 per centresp<strong>on</strong>ded positively - even though <strong>on</strong>ly 15 percent of all staff had used the EAP over the twoyears). Awareness of the service is high across allstaff groups - and there is some evidence thatwastage has also declined. Furthermore, thecompany feels it has a far better understanding of19Guidelines <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> counselling in the workplace© BACP <strong>2007</strong>

1.6 Existing recovery documentsPast recovery plans or documents with management recommendati<strong>on</strong>s exist <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> severalspecies covered by this plan (Appendix C).1.7 Roles and interests of Indigenous peopleThe requirements of the Native Title Act 1993 <strong>on</strong>ly apply to land where Native Title rightsand interests may exist. When implementing any recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s in this <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g>species plan where there has been no Native Title determinati<strong>on</strong>, or where there has beenno clear extinguishment of Native Title, c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> must be made as to the possibilitythat Native Title may c<strong>on</strong>tinue to exist.Generally, the Native Title Act 1993 requires certain procedures to be followed prior toundertaking activities that may affect Native Title rights and interests. Such activities areknown as future acts, and these may include certain recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s in this plan. Theadopti<strong>on</strong> of this plan will be subject to any Native Title rights and interests that mayc<strong>on</strong>tinue in relati<strong>on</strong> to the land and/or waters.Nothing in the plan is intended to affect Native Title. The relevant provisi<strong>on</strong>s of the NativeTitle Act 1993 should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered be<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e undertaking any future acts that might affectNative Title. Procedures under the Native Title Act 1993 are additi<strong>on</strong>al to those requiredunder the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1998.A draft of this recovery plan has been referred to the Aboriginal Partnership Unit of theDepartment <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment and Heritage, who will undertake c<strong>on</strong>sultati<strong>on</strong> with relevantIndigenous communities. This c<strong>on</strong>sultati<strong>on</strong> will determine the role and interests ofIndigenous communities with regard to the implementati<strong>on</strong> of this plan.1.8 Benefits to other species/ecological communitiesThreatened <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery work has anticipated benefits <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> many fauna species andplant communities <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>. Objectives within the plan strive towards holistichabitat protecti<strong>on</strong> and management, strategic threat abatement, and increasingcommunity awareness of, and engagement in, c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> and sustainability issues.Benefits to vegetati<strong>on</strong> communitiesImportant vegetati<strong>on</strong> communities (DEH 2002) are expected to benefit from <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> example:• Sugar Gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) Woodlands (regi<strong>on</strong>ally Threatened <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><strong>Peninsula</strong>) – Part of Ir<strong>on</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e Mulla Mulla, Metallic Sun-orchid, Silver Daisy-bush andWinter Spider-orchid critical habitat. Also support the <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> Yellow-tailedBlack-Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus; state Vulnerable, regi<strong>on</strong>allyEndangered) and Comm<strong>on</strong> Brushtail Possum (Trichosurus vulpecular; stateVulnerable, regi<strong>on</strong>ally Rare)• Purple-flowered Mallee Box (Eucalyptus lansdowneana ssp. albopupurea),Drooping Sheoak (Allocasuarina verticillata) +/- Coastal White Mallee (E.diversifolia) Mallee and Woodland (regi<strong>on</strong>ally Rare <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>) – Part ofMetallic Sun-orchid critical habitat• Broad-leaf Box (Eucalyptus behriana) Woodland communities (regi<strong>on</strong>allyVulnerable) – Part of Jumping-jack Wattle critical habitat• <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> Blue Gum (Eucalyptus petiolaris) Woodlands (state Endangered) –Part of Fat-leaved Wattle critical habitat.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Plan</str<strong>on</strong>g>t species that are similar to the species included in this plan are expected to benefitfrom baseline data, m<strong>on</strong>itoring and research that addresses knowledge deficiencies andfuture trends in <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s. Gaining knowledge and addressing comm<strong>on</strong> threatsrelated to these similar plant species will improve our understanding of aspects such aslimited niches and the impact of climate change, failed and successful flowering<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 19

esp<strong>on</strong>ses, potential pests and diseases, pollinator needs, and fire sensitivity and necessity.Eighty-eight regi<strong>on</strong>ally <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species grow within the <strong>Eyre</strong> Hills IBRA subregi<strong>on</strong>(DEH-EGIS <strong>2007</strong>) and 20 state <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species occur within Priority 1 Focus WorkAreas (Table 30.3). These species are expected to benefit from the implementati<strong>on</strong> ofrecovery acti<strong>on</strong>s within these areas.Benefits to faunaThirteen state <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> fauna species are known to occur within Priority 1 Focus WorkAreas identified within this plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery. These and other faunaspecies are expected to benefit indirectly from acti<strong>on</strong>s that deliver broad-scaleimprovement to the landscape (e.g. envir<strong>on</strong>mental weed c<strong>on</strong>trol, more appropriate fireregimes, and habitat restorati<strong>on</strong> activities). Fauna are likely to directly benefit fromrecovery acti<strong>on</strong>s that focus <strong>on</strong> plants that provide them with shelter and food(e.g. prostrate or spiky plants that provide safe refuge <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> species such as reptiles, smallwrens and spiders). As an example, <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sandalwood plants provide shelter sites <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>native spotted Jezebel butterflies to breed and grow, and the butterflies’ larvae haveactually been observed growing better <strong>on</strong> Sandalwood than <strong>on</strong> any other plant species(DEC <strong>2007</strong>).Wattle species provide direct food resources (mainly seeds) to native ants and birds(e.g. cockatoos, Emus, Malleefowl), and indirect food resources to beetles and wasps,which eat mites and thrips feeding <strong>on</strong> wattle flowers (Tame 1992). H<strong>on</strong>eyeaters and birdspecies of c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> significance within the Koppio woodlands include the WesternGeryg<strong>on</strong>e (Geryg<strong>on</strong>e fusca; state Rare) and Diam<strong>on</strong>d Firetail (Stag<strong>on</strong>opleura guttata;state Vulnerable) (DEH-EGIS <strong>2007</strong>; DEH 2002; S Way [DEH] <strong>2007</strong>, pers. comm.). Each ofthese <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> bird species has been recorded within Priority 1 Focus Work Areasidentified within this plan (Table 30.3). Other species include the White-striped Freetail-bat(Tadarida australis), the Inland Freetail-bat (Mormopterus planiceps) and Greater L<strong>on</strong>gearedBat (Nyctophilus timoriensis; state Vulnerable), which flies above the vegetati<strong>on</strong>canopy searching <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> insects within dry woodlands across <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> (DEH-EGIS <strong>2007</strong>;DEH 2002; S Way [DEH] <strong>2007</strong>, pers. comm.).Benefits to ecosystem servicesEcosystem services are the natural processes that are resp<strong>on</strong>sible <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> clean air and water,and numerous other envir<strong>on</strong>mental goods such as pollinati<strong>on</strong> of crops and nativevegetati<strong>on</strong>, shade and shelter, maintenance of fertile soil, and climate regulati<strong>on</strong> (CSIROAustralia <strong>2007</strong>; Lindenmayer & Burgman 2005).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Recovery</str<strong>on</strong>g> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> critical habitat is expected to benefit symbiotic fungi(mycorrhiza) in the soil. Mycorrhiza assist with plant uptake of water, nutrients and traceelements, helping to produce terrestrial ecosystems that are more resilient to stresses, i.e.attack from pathogens and insects (Grey & Grey 2005).Threatened wattle (Acacia) and pea (Pultenaea) species, and other species in theLeguminoseae family, use symbiotic soil bacteria (Rhizobia spp.) to fix nitrogen. ‘Nitrogenfixing’plays an essential role in ecosystem functi<strong>on</strong> by producing nitrate and/oramm<strong>on</strong>ium, which benefits the whole system of plants and provides flow-<strong>on</strong> nitrogen toanimals (CILR <strong>2007</strong>).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Recovery</str<strong>on</strong>g> acti<strong>on</strong>s seeking to address <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> orchid reproducti<strong>on</strong> and recruitmentissues are expected to increase our understanding of invertebrates and pollinator species.Healthy invertebrate populati<strong>on</strong>s are an important foundati<strong>on</strong> to trophic systems thatsupport larger animals such as birds, bats and reptiles. In turn, these animals offer insect‘cleaning and pest c<strong>on</strong>trol services’, which are fundamental ecosystem services.20 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

1.9 Social and ec<strong>on</strong>omic impactsImplementati<strong>on</strong> of this recovery plan is not intended to cause significant adverse socialand ec<strong>on</strong>omic impacts. Beneficial social and envir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts are likely to resultfrom the implementati<strong>on</strong> of a significant number of the planned recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s. Suchbenefits include provisi<strong>on</strong> of funding and professi<strong>on</strong>al human resources to <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>,promoting and fostering cooperative community teamwork, and the development ofcommunity interest and skills in natural resource management. The recovery of vegetati<strong>on</strong>communities associated with <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>’s <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant species is expected toenhance ecosystem services, which may in turn benefit agricultural producti<strong>on</strong> andproduce positive social and ec<strong>on</strong>omic impacts.1.10 Evaluati<strong>on</strong> of plan per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>manceThe South Australian Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment and Heritage, in c<strong>on</strong>juncti<strong>on</strong> with therecovery team, will evaluate the per<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance of this recovery plan. The plan is to bereviewed within 5 years of its commencement (Table 31.2). Any changes to managementor recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s will be documented accordingly.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 21

2 Definiti<strong>on</strong>sWords and terms uncomm<strong>on</strong> to everyday language are used within this plan, with manyalso having very specific legal meanings (e.g. critical and potential habitat). For furtherdefiniti<strong>on</strong>s please refer to the glossary in Appendix B.2.1 Critical and potential habitatThis document is a regi<strong>on</strong>ally based recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> nati<strong>on</strong>ally <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g>occurring <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>. Critical and potential habitat occurring outside of the <strong>Eyre</strong><strong>Peninsula</strong> Natural Resources Management regi<strong>on</strong> is there<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>e not addressed in this plan.Under regulati<strong>on</strong> 7.09 of the Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Protecti<strong>on</strong> and Biodiversity C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> (EPBC)Regulati<strong>on</strong>s 2000, habitat critical to survival is defined as:• sites needed to meet essential life cycle requirements,• sites of food sources, water, shelter, fire and flood refuges or those used at othertimes of envir<strong>on</strong>mental stress,• essential travel routes between sites,• sites necessary <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed dispersal mechanisms to operate or to maintainpopulati<strong>on</strong>s of species essential to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> species or ecologicalcommunity,• habitat used by important populati<strong>on</strong>s,• habitat that is required to maintain genetic diversity, and/or• areas that may not be occupied by the species and/or ecological community, butthat are essential <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> the maintenance of those areas where they do occur.Critical habitatCurrent knowledge of the ecology and biology of nati<strong>on</strong>ally <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong><strong>Peninsula</strong> is c<strong>on</strong>sidered insufficient to precisely determine the spatial boundaries of criticalhabitat required under the EPBC criteria outlined above. For the purpose of this recoveryplan, known and historic distributi<strong>on</strong> mapping has been substituted as the interim criticalhabitat mapping <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>. Known distributi<strong>on</strong> meets themajority of EPBC criteria and will be used until critical habitat can be determined(<str<strong>on</strong>g>Recovery</str<strong>on</strong>g> Acti<strong>on</strong> 1c).Potential habitatPotential habitat is defined as habitat that is not critical to the current survival of<str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> species, but that may be important to the l<strong>on</strong>g term recovery of aparticular species as that species is encouraged to expand in distributi<strong>on</strong>. Twoper<str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>mance criteria in this plan (1c.2 and 1c.3) address mapping of potential habitat.2.2 Extent of occurrence and area of occupancyIUCN (2001) defines extent of occurrence as the area c<strong>on</strong>tained within the shortestc<strong>on</strong>tinuous imaginary boundary that can be drawn to encompass all the known (inferredor projected) sites of present occurrence of a tax<strong>on</strong> (Figure 2.1, Pictures A and B).The measurement of extent of occurrence may exclude disc<strong>on</strong>tinuities or disjuncti<strong>on</strong>swithin the overall distributi<strong>on</strong>s of taxa (e.g. large areas of obviously unsuitable habitat), butsee ‘Area of occupancy’. Extent of occurrence can often be measured by a minimumc<strong>on</strong>vex polyg<strong>on</strong> (the smallest polyg<strong>on</strong> in which no internal angle exceeds 180 degreesand which c<strong>on</strong>tains all the sites of occurrence) (IUCN 2001).22 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012

Key: (A) Is the spatial distributi<strong>on</strong> of known, inferred or projected sites of present occurrence. (B) Shows <strong>on</strong>epossible boundary to the extent of occurrence, which is the measured area within this boundary. (C) Shows<strong>on</strong>e measure of area of occupancy, which can be achieved by the sum of the occupied grid squares(IUCN 2001).Figure 2.1. Diagrams explaining extent of occurrence and area of occupancyArea of occupancyArea of occupancy is defined as the area within a species’ extent of occurrence that isoccupied by that tax<strong>on</strong> (Figure 2.1, Picture C). The measure reflects the fact that a tax<strong>on</strong>will not usually occur throughout the area of its extent of occurrence, which may c<strong>on</strong>tainunsuitable or unoccupied habitat. In some cases, the area of occupancy is the smallestarea essential at any stage to the survival of existing populati<strong>on</strong>s of a tax<strong>on</strong>. The size of thearea of occupancy will be a functi<strong>on</strong> of the scale at which it is measured, and should beat a scale appropriate to relevant biological aspects of the tax<strong>on</strong>, the nature of threatsand the available data.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012 23

2.3 Populati<strong>on</strong>s and sub-populati<strong>on</strong>sPopulati<strong>on</strong>The legal definiti<strong>on</strong> of a populati<strong>on</strong> is an occurrence of the species or community in aparticular area (EPBC Act 1999). A populati<strong>on</strong> is a group of c<strong>on</strong>specific individuals (i.e.bel<strong>on</strong>ging to the same species), comm<strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g>ming a breeding unit within which theexchange of genetic material is more or less unrestricted, and/or a group sharing aparticular habitat at a particular time (Lindenmayer & Burgman 1998). However, in theIUCN Red List criteria the term ‘populati<strong>on</strong>’ is used differently to its comm<strong>on</strong> biologicalusage, and populati<strong>on</strong> is defined as the total number of individuals of the tax<strong>on</strong> (IUCN2001).This plan uses the term ‘populati<strong>on</strong>’ in two slightly different ways. It refers to the whole <strong>Eyre</strong><strong>Peninsula</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> of a species, and it refers to populati<strong>on</strong>s where there is an obviousand large geographical separati<strong>on</strong> in locati<strong>on</strong>s of the same species.Sub-populati<strong>on</strong>Sub-populati<strong>on</strong>(s) are defined as geographically or otherwise distinct groups in thepopulati<strong>on</strong> between which there is little demographic or genetic exchange (typically <strong>on</strong>esuccessful migrant individual or gamete per year or less) (IUCN 2001).At the time of publicati<strong>on</strong> the genetic relati<strong>on</strong>ship between <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘populati<strong>on</strong>s’or ‘sub-populati<strong>on</strong>s’ <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong> is unknown, so the use of the terms ‘populati<strong>on</strong>’and ‘sub-populati<strong>on</strong>’ are based <strong>on</strong> presumed genetic exchange <strong>on</strong>ly.24 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Draft</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery plan <str<strong>on</strong>g>for</str<strong>on</strong>g> 23 <str<strong>on</strong>g>threatened</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>flora</str<strong>on</strong>g> taxa <strong>on</strong> <strong>Eyre</strong> <strong>Peninsula</strong>, South Australia <strong>2007</strong>-2012