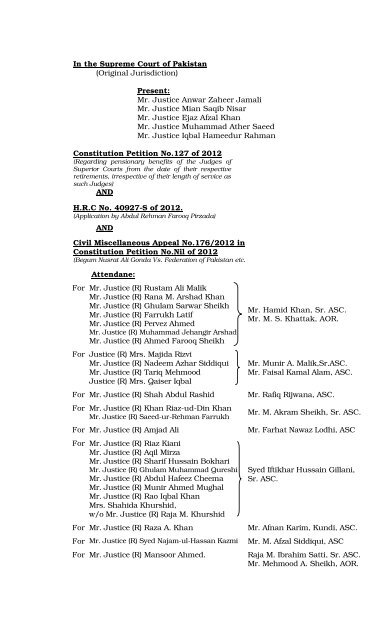

Mr. Justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar M

Mr. Justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar M

Mr. Justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar M

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 3On Court noticeOn Court notice(amici curiae):On Court’s Call:Dates of Hearing:<strong>Mr</strong>. Irfan Qadir, Attorney General for Pakistan.<strong>Mr</strong>. Azam Khan Khattak, Addl. AG., Balochistan.<strong>Mr</strong>. Muhammad Qasim Mirjut, Addl. AG, Sindh.<strong>Mr</strong>. Muhammad Hanif Khatana, Addl. AG PunjabSyed Arshad Hussain Shah, Addl: AG, KPKKhawaja Haris Ahmed, Sr. ASC<strong>Mr</strong>. Salman Akram Raja, ASC<strong>Mr</strong>. Abdul Qadeer Ahmed,Deputy Accountant General, Sindh.26 th , 27 th , 28 th , 29 th March, 2013 and2 nd , 3 rd , 8 th , 9 th , 10 th & 11 th April, 2013.JUDGMENT<strong>Anwar</strong> <strong>Zaheer</strong> <strong>Jamali</strong>, J.- By our short orderannounced in open Court on 11.4.2013, this case and the otherconnected cases were disposed of in the following manner:-“…..we hereby, in exercise of all the enabling powers vested inthis Court, hold and declare that the law enunciated in the caseof Accountant General Sindh and others versus Ahmed Ali U.Qureshi and others (PLD 2008 SC 522) is per incuriam andconsequently this judgment is set aside. The titled appeal isaccepted and the judgment impugned therein is also set aside.Other miscellaneous applications moved therein and in theseproceedings are dismissed accordingly.”In support of above short order, now we proceed to record ourdetailed reasons as under:-2. This Petition, for suo moto review of judgment dated6.3.2008, passed in Civil Appeal No.1021 of 1995, other connectedpetitions and miscellaneous applications, emanates from the officenote dated 21.11.2012 submitted by the Registrar of the SupremeCourt of Pakistan for the perusal of Honourable Chief <strong>Justice</strong>,which reads thus:-“It is submitted that the Civil Petition for Leave toAppeal No. 168-K of 1995 was filed in this Court by theAccountant General Sindh, challenging the validity ofthe judgment of High Court of Sindh, at Karachi, dated02.02.1995, wherein the Court had granted the relief ofpension to the respondent (since dead), a former judge

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 4of the High Court of Sindh, who while holding the postof District and Sessions Judge was posted as Secretaryto the Government of Sindh, Law Department and waselevated as Additional Judge, High Court of Sindh in1985. He retired on 25.10.1988 and was allowedpension at the rate of Rs.4,200 per month with thebenefit of commutation, gratuity and additional sum ofRs.2,100 per month as cost of living allowance payableto a retired Judge of the High Court under paragraph16-B of President's Order No.9 of 1970, as amended byP.O. No.5 of 1988. In pursuance of the Constitution(Twelfth Amendment) Act, 1991 (Act XIV of 1991), thepension of the respondent was revised and fixed asRs.6300 per month and thereafter by virtue of P.O. No.2of 1993, the pension of retired Judges of superiorjudiciary was again revised, wherein the pension of HighCourt Judges was fixed with minimum and maximumratio of Rs.9.800 and Rs.10,902 per mensum but thisincrease in pension was declined to the respondent onthe basis of departmental interpretation of thePresident's Orders referred to above read with FifthSchedule of the Constitution. The respondentthereafter, invoking the Constitutional jurisdiction ofthe High Court, filed a constitution petition wherein hesought a declaration that he was also entitled to thebenefit of P.O. No.2 of 1993. Relief was granted to himby the Sindh High Court. The Accountant General,Sindh feeling aggrieved approached this Court by filingsaid Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal.2. Leave to appeal was granted by this Courtvide order dated 28th August 1995, on the followingterms:"2. So far the main petition is concerned, it issubmitted by the learned Deputy Attorney General forthe petitioner that respondent No.1 was a District andSession Judge and was elevated as Judge of theHigh Court in July, 1985 and retired after completingtenure of three years two months and twenty-sevendays in that capacity, hence for the purpose ofpension his case is covered by Article 15 of the HighCourt Judges (Leave, Pension and Privileges) Order,1970, which is applicable to such judges of the HighCourt who retire before completion of five yearsservice in the High Court and are entitled to drawpension as having retired from the service they weretaken from for elevation to the High Court.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 53. Leave is granted to examine the followingquestions. Firstly, whether for claim of respondentNo.1 for extra/maximum pension writ petition beforethe High Court was competent to and maintainable.Secondly, whether P.O.9/70 is to be read inconjunction with P.O.2/93, P.O.3/95 and Article 205read with Fifth Schedule to the Constitution, if yes,what will be its effect on the claim of respondent.Thirdly, whether the President can only increase ordecrease the amount of pension with altering theterms and conditions as contemplated under Article205 read with the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution.Fourthly, whether respondent No.1 is entitled to theminimum and maximum amount of the pension ascontemplated under P.O.2/93."3. Pending disposal of the Appeal, a number ofother retired Judges of the High Courts, who were notallowed pension on the ground that they having beennot put minimum service of five years in terms ofparagraph 3 of Fifth Schedule to the Constitution werenot entitled to the grant of pension, moved a jointrepresentation to the President of Pakistan, through theMinistry of Law, <strong>Justice</strong> and Human Rights,Government of Pakistan and having received no reply,filed direct petitions before this Court under Article184(3) of the Constitution, whereas, some of the retiredJudges filed miscellaneous applications to be impleadedas party in the proceedings before this Court.Constitution Petition No.40 of 2002 filed by <strong>Mr</strong>. <strong>Justice</strong>(Retd) S.A. Manan was disposed of as withdrawn, but inview of the nature of right claimed in these petitions,this withdrawal was inconsequential to the right ofpension of the judges. The appellant in the main appealand the petitioners in the other constitution petitionssought declaration, as under:a. The provision of President's Order No.3 of1997 was in derogation to Article 205 of theConstitution read with Fifth Schedule of theConstitution wherein the right of pension ofonly those Judges who have put minimum fiveyears of service as Judge of the High Court,was recognized.b. The retired Judges of the High Court,irrespective of their length of service wereentitled to the grant of pension, as per theirentitlement under Article 205 read withparagraph 2 of the Fifth Schedule of theConstitution.4. On 06.3.2008, the Civil Appeal No. 1021 of1995 and the connected constitution petitions involving

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 6common question of law and facts, were disposed ofthrough the single judgment (PLD 2008 SC 522) bythree member Bench of this Court comprising <strong>Mr</strong>.<strong>Justice</strong> Nawaz Abbasi, <strong>Mr</strong>. <strong>Justice</strong> Muhammad QaimJan Khan and <strong>Mr</strong>. <strong>Justice</strong> Muhammad FarrukhMahmud in the following terms:“34. In consequence to the above discussion,the Constitution Petitions Nos. 8/2000,10/2001, 26/2003, 34/2003, 04/2004 and26/2007, filed by the retired Judges of theHigh Courts are allowed and thepetitioners/applicants in these petitions andmiscellaneous applications, along with allother retired Judges of the High Courts, whoare not party in the present proceedings, areheld entitled to get pension and pensionarybenefits with other privileges admissible tothem in terms, of Article 205 of theConstitution read with P.O.No.8 of 2007 andArticle 203-C of the Constitution read withparas 2 and 3 of Fifth Schedule and P.O. No.2of 1993 and P.O.3 of 1997 from the date oftheir respective retirements, irrespective oftheir length of service as such Judges.”5. It is evident from the above that the matterwas decided on the basis of High Court Judges(Pensionary Benefits) Order, 8 of 2007. This Order waspromulgated on 14.12.2007 and at the time of decisionof the matter was considered as a valid piece oflegislation. But subsequently, vide this CourtJudgment dated 31.07.2009 (Sindh High Court BarAssociation V. Federation of Pakistan), reported as (PLD2009 SC 879) this P.O 8 of 2007 was declaredunconstitutional, illegal, ultra vires and void ab initio.The relevant paragraph of said judgment is reproducedas under:“179. All the acts/actions done or taken by GeneralPervez Musharraf from 3rd November, 2007 to 15thDecember, 2007 (both days inclusive), that is to say,Proclamation of Emergency and the subsequent'acts/actions done or taken in pursuance thereof,having been held and 'declared to be unconstitutional,illegal, ultra vires and void ab initio are not capable ofbeing condoned. These include Proclamation ofEmergency and the PCO No.1 of 2007 issued by himas Chief of Army Staff and Oath Order, 2007 issuedby him as President of Pakistan in pursuance of theaforesaid two instruments, all dated 3rd November,2007; Provisional Constitution (Amendment) Order,2007 dated 15 th November, 2007; Constitution(Amendment) Order, 2007 (President's Order No.5 of2007 dated 20th November, 2007); Constitution(Second Amendment) Order, 2007 (President's OrderNo.6 of 2007 dated 14th December, 2007);, Islamabad

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 7High Court (Establishment) Order 2007 (President'sOrder No.7 of 2007 dated 14th December 2007); HighCourt Judges (Pensionary Benefits) Order, 2007(President's Order No.8 of 2007 dated 14thDecember, 2007) and Supreme Court Judges(Pensionary Benefits) Order, 2007 (President'sOrder No.9 of 2007 dated 14th December, 2007).The aforesaid actions of General Pervez Musharraf arealso shorn of the validity purportedly conferred uponthem by the decisions in Tikka Iqbal MuhammadKhan's case. The said decisions have themselves beenheld and declared to be coram non judice and nullityin the eye of law. The amendments purportedly madein the Constitution in pursuance of PCO No. 1 of 2007themselves having been declared to beunconstitutional and void ab initio, all the actions ofGeneral Pervez Musharraf taken on and from 3rdNovember, 2007 till 15th December, 2007 (both daysinclusive) are also shorn of the validity purportedlyconferred upon them by means of Article 270AAA.”6. It is further submitted that the issue in handhas far reaching implications. The practical effect of thejudgment is that Judges of the superior courts arebeing granted pension and pensionary benefits withoutany consideration of tenure or length of service.7. It is pointed out that Supreme Court in thecase of Province of Punjab v. Dr. Muhammad DaudKhan Tariq (1993 SCMR 508) held that it is not againstany principle for the Courts of this country to protectthe interest of the tax-payers as well as the publicexchequer notwithstanding the follies or illogical andsome times even casual attitude of the custodians of thepublic exchequer. Furthermore, this Court in the caseof Secretary, Board of Revenue, Punjab v. Khalid AhmadKhan (1991 SCMR 2527) held that the Government haschosen to spend much more on the litigation instead ofpaying Rs. 15,000 as judgment-debt to the respondenttowards the discharge of the decree in case wheresubstantial justice has been done. Further, althoughthe law point has been decided in favour of theappellants yet in the interest of justice we do not wantto inflict further heavy burden on the public exchequer;which would indeed be burdened with more expenses.8. The matter is therefore of great publicimportance as huge public money is being expendedwithout any legal justification despite the fact that thebasis of judgment itself has lost its validity. It istherefore a fit case for Suo Moto Review.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 89. There are precedents, when this Court tookup issues suo moto in the interest of justice. In the caseof rowdysim in the Supreme Court premises titledShahid Orakzai v PML(N) (2000 SCMR 1969), a Bench ofthree Judges acquitted the contemnor. CriminalOriginal Petition was filed by the Petitioner and thesame was heard by a Bench of 5 Judges and the samewas converted into Appeal. It was objected that thematter could not be reviewed by filing a CriminalOriginal Petition by a third person who was not party inthe matter. However, the Counsel for the Contemnerconceded that this Court is not precluded from recallingof its earlier order by taking Suo Moto action on comingto know that such miscarriage of justice had occurreddue to the Court having proceeded on wrong premises.It was held that under Article 187(1) of the Constitution,Supreme Court can recall its earlier order by taking SuoMoto action on coming to now that sum miscarriage ofjustice has occurred. In yet another judgment, whentwo different interpretations by two Benches of theSupreme Court taking contrary views of the judgment ofShariat Appellate Bench passed in a pre-emption caseof Said Kamal Shah, a Suo Moto Review (PLD 1990 SC865) was taken by the Shariat Appellate Bench to clarifythe effect of its judgment given in the said case. Again,it was held in the case State v. Zubair (PLD 1986 SC173) that if a Judge of High Court had heard a bailapplication of an accused person, all subsequentapplications for bail of the same accused or in the samecase, should be referred to the same Bench/Judgewherever he is sitting and in case it was absolutelyimpossible to place the second or subsequent bailapplication before the same Judge, who had dealt withthe earlier bail application of the same accused or in thesame case in such cases, the Chief <strong>Justice</strong> of theconcerned High Court may order that it be fixed fordisposal before any other Bench/Judge of that Court.The Supreme Court by taking suo moto action of thedifficulties arising out of the strict implementation ofthe ratio in the State v. Zubair and on receipt of thereports from the High Courts and hearing the AttorneyGeneral of Pakistan and Advocates-Generals of the

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 9Provinces it was observed (2002 SCMR 177) that thespirit underlying the said case which still held the filedwas not intended to create difficulties/bottlenecks or towork prejudicially to the interest of all concerned. It washeld that the rule laid down in the above case shallcontinue but due to exigency of service or any othersufficient cause departure can be made in the largeinterest of justice and may be referred to any otherbench for reason to be recorded in writing by the Chief<strong>Justice</strong>. Recently, a Constitution Petition filed forrevisiting of this Court judgment dated 13.9.2011passed in Constitution Petition No. 50/2010 fordeclaratory judgment regarding existence of Article186A of the Constitution was treated as Civil MiscApplication (CMA No. 4711/2012 in ConstitutionPetition No. 50/2010) for the purpose, which awaitshearing before the Court.10. In view of the above, if approved, Suo Motoaction may be taken in the matter for review ofjudgment dated 6.3.2008 passed in Civil Appeal No.1021 of 1995 etc and the matter may be fixed before aLarger Bench comprising minimum five members.Registrar21.11.2012HCJ 223. Taking notice of the facts and circumstances disclosed inthe above reproduced submission note, coupled with the legalposition canvassed therein for taking cognizance in the matter, on23.11.2012, following order was passed by the Honourable Chief<strong>Justice</strong> of Pakistan:-“Perusal of above note prima facie makes out a casefor examination of points raised therein. Therefore,instant note be registered as Suo Motor Misc.Petition and it may be fixed in Court in the weekcommencing from 03.12.2012. Notice to Hon’bleRetired Judges, who are beneficiaries of thejudgment dated 6.3.2008 be issued. Office shall

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 10provide their addresses. Notice to Attorney Generalfor Pakistan may also be issued.”.It is in this background that subsequently this petition cameup for hearing before this five member larger Bench:-4. At the commencement of the proceedings in the matter,Syed Iftikhar Hussain Gillani, learned senior ASC, representingeight of the honourable retired judges of the High Court, M/s RiazKiyani, Muhammad Aqil Mirza, Sharif Hussian Bukhari, GhulamMehmood Qureshi, Abdul Hafeez Cheema, Dr. Munir AhmedMughal, Tariq Shamim and Rao Iqbal Ahmed Khan, JJ and thewidow of one honourable retired Judge Raja Muhammad Khurshid,who have been issued notices of these proceedings, came at therostrum and made his submissions as one of the lead counsel forthese judges.5. At the outset, he gave a brief summary of the relevantfacts regarding the services rendered by the judges represented byhim, to show their actual period of service as judge of the HighCourt before becoming entitled for pensionary benefits in the lightof judgment dated 6.3.2008, passed in civil appeal No.1021/1995and other connected petitions (PLD 2008 SC 522), (hereinafterreferred to as the “judgment under challenge”). In the samecontext, he also made reference of C.M.A No.802/2013, whichcontains relevant facts as regards their respective service as judgeof the High Court. He further made reference to the statement inwriting subsequently submitted by him, containing theformulations of his arguments, which read as under:-“a.Entitlement to the remuneration of the Judges of the SuperiorCourts are guaranteed by the Constitution and no Sub-Constitutional legal instrument can take away such entitlement.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 11b. Para 2 in the V th Schedule is an independent provision and is notto be ‘governed’ by Para 3.c. Dictum of Qureshi’s judgment reported in PLD 2008 SC 522 wasnot decided ‘on the basis’ of the Presidential Order 8 of 2007, asobserved in para 5 of learned Registrar’s note, but founded on themandate of the Constitution.d. That High Court Judges (Leave, Pension and Privileges) Order,1997 (President’s Order 3 of 1997) is violative of Article-205 andSchedule V of the Constitution.”6. The learned Sr.ASC referring to some legal aspects of thecontroversy involved in the present petition, made specificreference to all the relevant statutes starting from the Governmentof India Act, 1935 upto the Constitution of 1973 as well as variousorders and President’s Orders issued in this regard from time totime. Making reference to the language of Article 205 read withparagraph-2 of its Fifth Schedule, relating to High Court judges, heemphasized that the language of paragraph-2 of the FifthSchedule, commencing from the word “Every judge” makes itabundantly clear that irrespective of his length of service, everyjudge, once elevated to the High Court is entitled, inter alia, for thepensionary benefits while the authority for determination vestedwith the President in terms of this para is only confined to thequantum of such pension and nothing more. He added thatparagraph-3 of the Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of theConstitution, which was available in the original text of theConstitution of 1973, and subsequently amended in the year 1991,was to be read independent and separate from paragraph-2, whichprovides for pensionary benefits for the two categories of thehonourable retired judges, depending upon their length of service,when read in conjunction with it. He reiterated that every judge ofthe High Court is entitled for pensionary benefits, but for thedetermination of quantum of such benefit, they are categorized

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 12into two; one, who have served as such for a period of five years ormore and, the others, having served for less than five years.According to <strong>Mr</strong>. Gillani, insofar as the entitlement of pensionarybenefits of those judges of the High Courts is concerned, who haverendered more than five years of service, there is no dispute orcontroversy at all about their entitlement of pensionary benefits.However, for the other category of judges, having rendered lessthan five years actual service, till date no independentdetermination, as required by law and under the Constitution, hasbeen made by the President. At this stage, he also made referenceto the judgment under challenge to show that it was in thisbackground of the controversy that this Court resolved the issue ofpensionary benefit of all the retired judges, including those, whohave rendered less than five years service, and such conclusionbased on valid reasonings is not open to interference in any form.More so, in a situation when such judgment was passed more thanfour years ago; it has already been implemented in its letter andspirit, and not challenged by the Government or from any othercorner.7. Touching to the moral side of this controversy relating topayment of pension, he further argued that all judges of thesuperior judiciary, including those who have retired from theiroffice before rendering complete five years actual service as HighCourt Judge, are highly respected segment of the society, who needto maintain special protocol befitting to their earlier status andoffice; further in terms of Article 207 of the Constitution, they aredisqualified to practice in the same High Court. In suchcircumstances, merely due to the fact that they have rendered less

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 13than five years of service in the said position, they cannot bediscriminated and deprived of such benefit, which in turn would,in many cases, result in leaving them at the mercy of the societyfor the purpose of meeting their financial needs in the old age. Inorder to gain support to his submissions, learned Sr. ASC furthermade reference to 12 th Constitutional Amendment; President’sOrder No.2 of 1993 (PLD 1994 C.S 192) and President’s Order No.5of 1996 (PLD 1997 C.S 199) and relied upon the cases reported asM.A Rashid v. Pakistan (PLD 1988 Quetta 70), Ahmed Ali U.Qureshi v. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 1995 Karachi 223) and I.ASharwani v. Government of Pakistan (1991 SCMR 1041). Amongstthese cases, in the 1 st case decided by learned Division Bench ofBalochistan High Court on 08.5.1988, a dispute was agitated byhonourable retired <strong>Justice</strong> M.A Rashid, as regards the entitlementof his pensionary benefits under the High Court Judges (Leave,Privileges and Pension) Order, 1970 qua the effect of amendingorder 5 of 1983, of which benefit was refused to him. In this case,the honourable Judge of the Balochistan High Court had initiallyadorned the office in that position on 07.10.1974, after beingelevated to the High Court of Sindh and Balochistan. Thereafter heceased to hold the office as Judge of the Balochistan High Courtw.e.f. 25.3.1981, after having served for a period of more than sixyears. The Court, while holding him entitled for the benefit ofamending order 5 of 1983, concluded that Constitution is afundamental document and while interpreting a provision of theConstitution, article thereof must receive a construction whichwould be beneficial to the widest maximum extent. Moreover,making reference to some Presidential Orders, the Court observedthat such Orders nowhere stipulate that the benefit of these

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 14Presidential Orders would not be available to the Judges who hadretired before the dates mentioned in the two orders, as the Ordersare clear and admit of no ambiguity, therefore, the necessaryconclusion would be that the benefit of these Orders would beavailable to all the Judges irrespective of their date of retirement.The 2 nd case of Ahmed Ali U. Qureshi (supra), need not bediscussed here as it was against the same judgment that an appealwas preferred before this Court, which was decided vide judgmentunder challenge dated 6.3.2008. The 3 rd case of I.A Sharwani(supra) is also not being discussed here as it will be discussed indetail in some later part of the judgment.8. At the conclusion of his arguments, <strong>Mr</strong>. Gillani also madereference to Article 260 of the Constitution to show the definition of‘remuneration’, which includes the word ‘pension’, however, whenconfronted with other definitions contained in this Article, heconceded that since ‘pension’ has been separately defined therein,therefore, its inclusion in the definition of “remuneration” will notmake much difference.9. After conclusion of arguments of <strong>Mr</strong>. Iftikhar HussainGillani, <strong>Mr</strong>. Munir A. Malik, learned Sr. ASC, who is representingfour other honourable retired judges M/s Majida Rizvi, NadeemAzhar Siddiqui, <strong>Mr</strong>s. Qaiser Iqbal and Tariq Mehmood, JJ, came atthe rostrum and made his submissions. In the first place, he madereference of C.M.A’s No.867 to 869 of 2013, to give some detailsabout the services rendered by each one of them as honourablejudge of High Court, particularly the dates of their appointment asan additional judge, permanent judge; and retirement/resignation,with total length of their respective service. Before commencing his

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 15arguments on legal footing, <strong>Mr</strong>. Malik, frankly stated that none ofthe retired judge of the High Court represented by him hasrendered actual service as such for a period of five years, but lessthan five years. In the context of entitlement of pensionarybenefits, he gave brief history of constitutional legislation andother provisions of law including the President’s Orderspromulgated/ issued in the sub-continent before and after theindependence of Pakistan from time to time and reiterated thatparagraph-2 of the Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of the Constitutionof 1973 is to be read independently; it covers the right of “everyjudge” of the High Court for the purpose of pensionary benefit to bedetermined by the President, therefore, irrespective of the factwhether no such determination has yet been made by thePresident for the category of those honourable retired judges of theHigh Court, who have rendered service as such for less than fiveyears, they are entitled for the pensionary benefits. Whenconfronted with the query as to how and in what manner thequantum of such pension for these judges could be determined, ifno mode of determination in this regard is available before us inany form, he candidly stated that as yet no such determination hasbeen made by the President even once, nor this matter was earlieragitated by any of the honourable retired judge of the High Court,who had rendered less than five years of service in the said office,since the promulgation of the Constitution of 1973 or even beforethat under the Constitution of 1956 or 1962 etc. The pith andsubstance of his submissions was that “every judge” as mentionedin paragraph-2 of the Fifth Schedule to Article 205, has its ownconnotation and significance which makes it abundantly clear thatthey all are entitled for pensionary benefits, but only the questionof determination of quantum of pension is left with the President in

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 16line with the spirit of paragraph-2 and nothing more. For thisreason, in either of the two situations when paragraph-2 is readseparately, independently and hermetically or together withparagraph-3, the claim of every retired judge of the High Court forpensionary benefits is fully established. In order to add force to hissubmissions about the entitlement of every judge of the High Courtfor pensionary benefits, he also laid stress upon Article 207 of theConstitution, which places an embargo on every honourable retiredjudge of the High Court from practicing within the territorial limitsof the same High Court, wherein he has served as a permanentjudge even for a single day. In between the lines, his submissionwas that when such an embargo becomes operative againsthonourable retired judges soon after their confirmation then thecondition of five years minimum length of service for theirentitlement to pension as judge of the High Court seems to beinconsistent, illogical, harsh and violative of Article 18 of theConstitution. He also made reference to the National JudicialPolicy 2009 and 2012 and contended that even after retirement,honourable judges of the High Court are required to maintainbefitting standard of living in the society, which may not bepossible for them under financial constraints, thus, their claim forentitlement of pension even for less than five years actual service isfully justified and in accordance with law. However, he added that,indeed, retired judges of the High Court, who have rendered lessthan five years service as such and those who have rendered fiveyears or more service, cannot be placed in the same category forthe purpose of pensionary benefits. He also conceded to theposition that as yet, not even once any determination regardingpensionary benefits of honourable retired judges, who haverendered less than five years service, has been made by the

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 17President and such purported inaction on his part has never beenchallenged earlier in the history of the Sub-continent and ourCountry either under the dispensation of Government of India Act,1935 or the Constitutions of 1956, 1962 and 1973, except thepresent litigation emanating from the case of Ahmed Ali U.Qureshi. In his further submissions learned ASC also dilated uponthe concept of independence of the judiciary as a third pillar of theState, which, according to him, also covers its financialindependence qua right to pension for every judge of the HighCourt irrespective of his length of service in the office.10. <strong>Mr</strong>. Munir A. Malik, learned Sr. ASC in his furtherarguments, made reference to the office note dated 21.11.2012,submitted by the Registrar of Supreme Court of Pakistan for theperusal of Honourable Chief <strong>Justice</strong> of Pakistan, which formedbasis of these proceedings and contended that no doubt videjudgment in the famous case of Sindh High Court Bar Associationv. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 2009 SC 879), President’s OrdersNo.8 of 2007 dated 14.12.2007 and Judges Pensionary BenefitsOrder 9 of 2007, have been declared to be coram non judice andnullity in the eyes of law, but on the basis of this case alone, thejudgment under challenge cannot be set aside, as many otherstrong independent reasons have been recorded in its paragraphs1 to 19, which still hold the field as alternate grounds for grant ofpensionary benefits. Further submissions of <strong>Mr</strong>. Malik was thateven if the Court comes to the conclusion about the nonentitlementof pensionary benefits for the honourable retiredjudges of the High Court, having rendered less than five yearsservice, keeping in view their high status in the society andbonafide implementation of the judgment under challenge, any

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 18order contrary to it, if passed, should be made operativeprospectively and not retrospectively. During his furtherarguments, <strong>Mr</strong>. Munir A. Malik, made detailed reference of P.ONo.9/1970, PO No.7/1991, P.O No.2/1993, P.O No.3/1995, P.ONo.5/1995, P.O No.3/1997 and 12 th Constitutional Amendment inan effort to show that it will be a legitimate and holistic approach ifthe claim of honourable retired judges of the High Court, who haverendered less than five years actual service, is looked intopragmatically and liberally in order to determine their right andquantum of pension, which exercise has not yet been undertakenby the President, though required under the mandate of theConstitution. Making reference to the case of one of the honourableretired judge of Sindh High Court Ms. Majida Rizvi, he also broughtto our notice the judgment dated 1.7.2008 in C.P No.D-24/2002,which remained unchallenged till this date and has, thus,according to him, attained finality. In the end, he made referenceto the principles of locus poenitentiae etc and cited the followingcases:-a) Attiyya Bibi Khan v. Federation of Pakistan(2001 SCMR 1161).b) M/s Haider Automobile Ltd v. Pakistan(PLD 1969 SC 623).c) Elahi Cotton Ltd. v. Federation of Pakistan(PLD 1997 SC 582).d) Amir Khatoon v. Faiz Ahmad (PLD 1991 SC 787).e) R v. A [2001 (3) All England Reporter 1 (17)].11. In the case of Attiyya Bibi Khan, relating to some disputebetween the students of a medical college and the educationalinstitutions, the provisions of Article 25 of the Constitution weredilated upon and in that context it was held that the judgment

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 19would be operative from the date of its announcement and wouldhave no retroactive legal implications. In the case of M/s HaiderAutomobile Ltd (supra) and other connected case titled Province ofWest Pakistan versus Manzoor Qadir Advocate and another,dispute revolved around the availability of right of practice to aretired judge of the High Court of West Pakistan in view of the barimposed by Ordinance II of 1964. The Court held that thelegislature is competent to make a law and has full and plenarypowers in that behalf and can even legislate retrospectively orretroactively. There is no such rule that even if the Legislature has,by the use of clear and unambiguous language, sought to takeaway a vested right, yet the Courts, must hold that such alegislation is ineffective or strike down the legislation on theground that it has retrospectively taken away a vested right. Afterdetailed discussion, the learned five members Bench of the apexCourt unanimously held that the two learned former judges weredebarred by Ordinance No. II of 1964 from practicing in the HighCourt of West Pakistan or any Court or tribunal subordinate to it.In the case of Elahi Cotton Ltd, discussing some broad principlesof interpretation of statutes qua constitutional provisions viewexpressed by the Court was that the law should be saved ratherthan be destroyed and the Court must lean in favour of upholdingthe Constitutionality of a legislation, keeping in view that the ruleof Constitutional interpretation is that there is a presumption infavour of the Constitutionality of the legislative enactments unlessex facie it is violative of a Constitutional provision. It was furtherheld that where power is contained in the Constitution to legislate,one's approach while interpreting the same should be dynamic,progressive and oriented with the desire to meet the situation,

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 20which has arisen, effectively. The interpretation cannot be narrowand pedantic, but the Court's efforts should be to construe thesame broadly; so that it may be able to meet the requirements ofan ever changing society. The general words cannot be construedin isolation but the same are to be construed in the context inwhich they are employed. In other words, their colour and contentsare derived from their context. In the case of Amir Khatoon, incriminal proceedings, principle of interpretation of statute wasdiscussed and it was held that if a provision of law is presentingsome difficulty in interpretation, it has to be so interpreted as toharmonise with the other provisions of the Act of which it is a partand it is only when there is a manifest and established failure toharmonise it with the other provisions that it either prevails overother provisions or yields to the other provisions. It was furtherobserved that provisions of any particular Act are to be sointerpreted as to harmonise and to remain consistent with theother laws having a relevance or nexus with the law sought to beinterpreted. In the case of R v A, involving criminal proceedingsrelating to some sexual offence, expressing his view on theprinciple of reading down, it was observed by a learned Member ofthe Bench that this principle is at least relevant as an aid to theinterpretation of section 3 of the 1998 Act against the executive. Asin accordance with the will of parliament reflected in section 3, itwill sometimes be necessary to adopt an interpretation whichlinguistically may appear strained. The techniques to be used willnot only involve the reading down of express language in a statutebut also the implication of provisions. A declaration ofincompatibility is a measure of last resort. It must be avoidedunless it is plainly impossible to do so. If a clear limitation on

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 21convention rights is stated in terms, such an impossibility willarise.12. At this stage, <strong>Mr</strong>. Rafique Rijwana, learned ASC, who isrepresenting honourable retired <strong>Justice</strong> Shah Abdul Rasheed inthese proceedings, made his submissions. He gave relevant datesof his appointment and retirement to show that at the time ofretirement on 11.2.1986, he had served as a judge of the HighCourt for 04-years, 07-months and 05-days. He did not advanceany further arguments except adopting the arguments of SyedIftikhar Hussain Gillani, learned senior ASC, who has alreadymade his submission in this case, as noted above.13. <strong>Mr</strong>. Hamid Khan, learned Sr. ASC, who is representingseven honourable retired judges of the High Court, at thecommencement of his submissions, made reference to the materialplaced on record by him alongwith C.M.As No.847 to 853 of 2013to give details regarding the service of each of the honourableretired judges represented by him, so as to show their actuallength of service as judges of the High Court. For the purpose ofclearity in his arguments, he divided the honourable retired judgesrepresented by him into two categories i.e. Rana MuhammadArshad Khan and Muhammad Jehangir Arshad, two honourableretired judges, who were elevated to the Bench from the bar andthe remaining five retired judges, who before their elevation, hadrendered about thirty years service in the District judiciary indifferent capacities. Details of these honourable retired judges andother judges in similar position, regarding service rendered bythem, is being provided in the judgment separately in the form of achart.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 2214. <strong>Mr</strong>. Hamid Khan, during his arguments, also placed onrecord written formulations, which read as under:-1. “Para 2 of the schedule 5 has an independent existencefrom that of para 3 and cannot be read as superfluousor redundant, therefore, under the recognized principlesof independence of the Constitution, the Court is calledupon to give comprehensive meaning to this para.2. Despite having independent existence para 2 has to beread with para 3 in order to give meaning of the formerpara, if read together they would cater for two distinctclassifications, one of those who had put in five or moreyears of service and the other of those who have put inless than five years of service and finally within thisformulation that those, who belonged to each of theclassification, are entitled to pension and none of themcan be deprived thereof.3. Reading of two paragraphs together, it can also beconstrued that para 3 lays down a bench mark for thosewho are entitled to pension under para 2, this wouldlead to the exercise of principle of proportionalitynevertheless if will not apply to the petitioners becausesuch a principle can only be applied prospectively.4. That having received pension under a judicialdetermination rights have been vested in favour of thepetitioners which cannot be taken away at this stageunder the established exception to the principle of locuspoenitentiae.5. Having once received pension under the judicialdetermination there is legitimate expectancy on the partof the petitioner to continue to receive such pensionaryamounts, any deprivation at this stage would lead toprivation and financial problems to the petitioners whoare of advanced age.6. There is a special case relating to judges elevated fromthe subordinate judiciary because:-a. They had put a long service before they becomeJudges of the High Court;b. They cannot be relegated to the position of thosewho retired as District Judges and so they cannotbe given the pension of District and SessionJudges.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 23c. Doing so would be against the independence ofJudiciary and would undermine the office of aJudge of a High Court.”15. He contended that paragraph-2 of Fifth Schedule toArticle 205 has an independent existence from paragraph-3,otherwise this paragraph would become superfluous andredundant, which status cannot be attributed to any piece oflegislation, as under the well recognized principle of interpretation,every provision of law is to be given its comprehensive meaning.Following the arguments of earlier two learned ASCs, who haveargued the case before him, he insisted that paragraph 2 of FifthSchedule to Article 205 visualizes two categories of judges, butboth of them are equally entitled for pensionary benefits under thePresident’s Orders and in this regard power of determinationconferred to the President is only confined to the quantum ofpensionary benefits and not the determination of right to pensionor otherwise. He further contended that reading of paragraph-2together with paragraph-3 lays down benchmark for those who areentitled under paragraph-2 and in case no determination has beenmade by the President for entitlement of pension of retired judgesof the High Court who have rendered less than five years of actualservice, the principle of proportionality could be applied, but thattoo only prospectively, as the rights accrued and benefits alreadydrawn by the honourable retired judges of the High Court throughjudgment under challenge cannot be withdrawn, being staredecisisand past and closed transaction under a judicialpronouncement. He further submitted that on account of suchjudicial determination, vested rights have accrued in favour ofhonourable retired judges, which cannot be taken away orwithdrawn, being protected under the principle of locus

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 24poenitentiae. To a question posed to him, whether on the principleof locus poenitentiae, retired judges represented by him seekprotection of only those benefits which have already been drawn bythem or also continuation of such benefits in future, his reply wasthat the principle of legitimate expectancy has accrued in theirfavour to continue receiving such pensionary benefits, which areeven otherwise very necessary for them to meet their financialneeds at this advanced age. Therefore, such benefits in their favour(honourable retired judges of the High Court) shall be continued,irrespective of any adverse pronouncement by this Court in thepresent proceedings. Making his further submissions, he alsoattempted to press into service the principle of past and closedtransaction based on the premise that the judgment underchallenge was announced on 6.3.2008 i.e. more than four yearsago and has already been followed and implemented by theconcerned government functionaries without any objection.16. As to the claim of five honourable retired judges of theHigh Court, who were elevated to the bench after rendering morethan thirty years service in District Judiciary in each case, beforetheir elevation to the High Court, he further submitted that forgrant of pensionary benefits, they cannot be relegated to theposition of retired District and Sessions Judges as it will be a stepagainst the independence of judiciary which will be underminingthe status and office of the judge of a High Court. Making referenceto Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of the Constitution of 1973,Learned senior ASC submitted that the original paragraph-3 in theFifth Schedule was borrowed from the President’ Order 9 of 1970,though in the different form, which was subsequently amendedand introduced in the present form in the year 1991. When

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 25confronted with a query that in case paragraph-2 (ibid) is to beread independently and separately, then it contains and denotesonly one category of judges and not two, the learned Sr. ASCconceding to this position, criticized the language of paragraph-3(ibid) by submitting that it has been grafted and drafted in theConstitution of 1973 in a crude form so as to leave the honourableretired judges, who have served the institution for a period of lessthan five years, without entitlement of any pensionary benefits. Inthis regard, he also made reference to some relevant Indianprovisions of law and contended that there is no specificprohibition regarding the entitlement of payment of pension to thejudges who have rendered less than five years service in the HighCourt before their retirement either in paragraph-2 or paragraph-3of the Fifth Schedule to Article 205, therefore, the principle thatwhatever is not prohibited is permissible shall be applied on theprinciples of equity and fair-play to address the unforeseendifficulties of the honourable retired judges of the High Court. Thepith and substance of his arguments was that looking to theconstitutional provisions, status of honourable retired judges ofthe High Court in the society and their old age, a pragmaticapproach may be followed by the Court in order to accommodatethem for the purpose of granting them pensionary benefits, whichis lacking determination in specific terms by the President underany of the earlier President’s Orders issued from time to time.17. <strong>Mr</strong>. Amir Alam Khan, learned ASC, who is appearing inthis matter for five other honourable retired judges of High CourtM/s Muhammad Nawaz Bhatti, Fazal-e-Miran Chohan, SyedAsghar Haider, Sheikh Javed Sarfraz and Tariq Shamim, JJ, in hisarguments made reference of C.M.As No.803, 855, 856, 857 and

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 26858 all of 2013, filed in the form of concise reply and also gotrecorded their respective dates of appointments as additionaljudge/permanent judge of the High Court, date ofretirement/resignation as judge of the High Court, date ofsuperannuation and the actual period of their respective length ofservice as judge of the High Court. He candidly stated before usthat all the five honourable retired judges represented by him, arethose, who, for one or the other reason, have not rendered actualservice as a High Court Judge for five years or more and thus forthe purpose of pension, they have availed the benefit of judgmentunder challenge.18. As first limb of his arguments, <strong>Mr</strong>. Amir Alam Khanchallenged the maintainability of this petition on the ground thatadjudication made by a three member Bench of this Court inexercise of its appellate jurisdiction under Article 185(3) of theConstitution, has attained finality in all respect, rather it has beenimplemented by the concerned government functionaries in its letterand spirit more than four years ago. Thus, on any legal premisethese proceedings cannot be subjected to interference, if consideredto be proceedings under Article 184(3) of the Constitution, whichconfers only limited jurisdiction to this Court relating to the issuesinvolving question of public importance and for the enforcement offundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution. Hereiterated and added that the judgment under challenge is staredecisis, thus, final in all respect, and not open for reconsiderationin any manner, therefore, these proceedings are not maintainablein the present form. Discussing the fallout of judgment underchallange, he also made reference of Article 203C(9) of theConstitution to show that not only retired judges of the High Court

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 27having less than five years actual service to their credit havebecome entitled for pensionary benefits, but the Chief <strong>Justice</strong> andother honourable retired judges of the Federal Shariat Court havealso become eligible and entitled for pensionary benefits despitebeing contract employees for a fixed term of three years. Hisfurther submission was that since a pragmatic and liberalapproach has been followed by the Court in the judgment underchallenge, its spirit may not be negated only on technical groundsor the fact that while interpreting the relevant provisions of theConstitution and President’s Orders, another view of the matterprejudicial to the interest of the retired judges of the High Court,was also possible. <strong>Mr</strong>. Amir Alam Khan, when confronted with thequestion that in case judgment under challenge is found to be perincuriam then what will be its legal position, candidly stated thatin that eventuality it will be a judgment liable to be ignored for allintent and purposes, thus, the ground urged by him forchallenging the maintainability of these proceedings will not be anobstacle for the Court from adjudicating the case on merits.19. Learned ASC also made reference to paragraph 178 of thejudgment in the case of Sindh High Court Bar Association (supra)in support of his arguments that the judgment under challengehas been already protected by application of doctrine of de factoexercise of jurisdiction, and as such judgment has been passed bya 14 members Bench of the apex Court, therefore, such protectioncannot be taken away by a five member Bench for denying itsbenefit to the retired judges of the High Court. Dilating upon themoral side of these proceedings, learned ASC also argued that allthe honourable retired judges of the High Court, irrespective oftheir length of service, are highly respected segment of society, who

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 28deserve extra compassionate consideration in the matter of grantof pension and other benefits, therefore, once a judgment of thisCourt has remained in the field for a period over four years andfully acted upon, it shall not be withdrawn so as to take away allits benefits retrospectively, being past and closed transaction.Advancing his further arguments with reference to the case ofFazal-e-Miran Chohan, J., learned ASC pointed out that after hiselevation to the Bench as Additional Judge of the High Court w.e.f.1.12.2004 and confirmation vide notification dated 30.11.2005, heresigned from the service under very special circumstances on11.10.2009, though otherwise his date of superannuation was25.12.2010. Leaving apart these facts, which need sympatheticconsideration for extending him the pensionary benefits, in thismanner he has actually served as Judge of the High Court for aperiod of 04-years, 10-months and 09-days. Thus, upon readingpara 29 of President’s Order No.3 of 1997, together with serviceregulation No.423 of the Civil Service Regulations (in short “CSR”),providing for automatic relaxation/concession of six months incase of short service of a civil servant, he is otherwise also entitledfor pensionary benefits, independent to the ratio of judgmentunder challenge. In this context, he also placed reliance upon thecases Secretary Finance Division, Islamabad v. MuhammadZaman, Ex-Inspector, I.B., Islamabad (2009 SCMR 769) andMuhammad Aslam Khan v. Agricultural Development Bank ofPakistan (2010 SCMR 522). In the first case of Secretary FinanceDivision (supra), with reference to regulation No.423 of CSR, ofwhich benefit was claimed by the legal heirs of a deceasedgovernment employee/pensioner, it was held that regulationNo.423 of CSR is without any qualification and is not restricted to

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 29pensionary benefit of a widow. Of course, regulation No.423(2)empowers the competent authority to condone the deficiency ofmore than 6 months but less than one year where an officer hasdied while in service, or has retired under circumstances beyondhis control. In this context, the case of Postmaster-General EasternCircle (E.P.) Dacca and another v. Muhammad Hashim (PLD 1978SC 61) was also refered wherein it was held that if the Rules werecapable of bearing a reasonable interpretation favourable to theemployee then that interpretation should be preferred. In thesecond case of Muhammad Aslam Khan (supra), again the scope ofregulation No.423 of CSR was discussed with reference to the factsof the case, where a retired government servant, who had servedfor 31 years, 11 months and 14 days and was short of 17 daystowards completion of 32 years, was claiming pensionary benefitsfor 32 years. The Court held that regulation No.423(1) of CSRunder Chapter XVII with the heading "Condonation ofInterruptions and Deficiencies" would undoubtedly suggest thatthe shortage of period not exceeding six months becomeautomatically condoned, rather shortage of period exceeding sixmonths was also condonable by competent authority, providedthe conditions under regulation No.423(2) of CSR were fulfilled.20. At the conclusion of his arguments he also pointed outthe incident of plane crash, which took the life of honourable<strong>Justice</strong> Muhammad Nawaz Bhatti in the line of his duty on10.7.2006, who otherwise would have reached the date of hissuperannuation on 31.8.2009, after rendering service of roughly04-years and 09-months. In this context, he stressed for a mercifuland lenient view in the matter for the widow and orphans of thedeceased judge.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 3021. <strong>Mr</strong>. Muhammad Akram Sheikh, who is representingbefore us M/s Saeed-ur-Rehman Farrukh and Khan Riaz-ud-DinAhmed, JJ, at the commencement of his arguments madereference of C.M.A No.871 and 872 of 2013 to give relevant dates oftheir appointment as Additional Judges/permanent judges of theHigh Court and date of their retirement on 31.7.1998 and31.12.1997 respectively. According to his calculations, the actualperiod of service rendered by them, including the period of gap intheir service, both of them have served as a Judge of the HighCourt for a period of more than five years and thus, their cases arenot covered by the ratio of judgment under challenge and they are,therefore, not its beneficiary. Further, according to learned ASC,issuance of notice of these proceedings to them is uncalled for andliable to be withdrawn/set aside. However, when we have lookedinto some relevant factual aspects of the case in the context oftheir actual period of service as judge of the High Court, we havenoticed that they have served as such for a period of about 03-years, 06-months and 12-days; and 04-years, 02-months and 28-days respectively, if the period when they remained out of serviceas Judge of the High Court is excluded from consideration in linewith the definition of actual period of service given underparagraph-2 of President’s Order No. 3 of 1997, which provides foronly computing the actual service for eligibility and payment ofpensionary benefits. Learned ASC making reference to FifthSchedule to Article 205 of the Constitution, also attempted to showthe element of discrimination in the matter of entitlement ofpensionary benefits for a retired judge of the High Court and aretired judge of the Supreme Court, as separately provided in thesaid Schedule. In this regard, his submission was that no

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 31minimum period of service as a judge of the Supreme Court isprescribed in the first part of the Schedule relating to right topension while the condition of minimum five years service forentitlement of pensionary benefits has been discriminately madeapplicable for the retired judges of the High Court. Learned ASC,during his arguments, also made reference to the case of I.ASharwani (supra), to lay stress to his arguments upon the right ofpension to a retired civil servant.22. In addition to the above, in his written submissions,learned ASC further reiterated as under:-a. Notice issued to the retired judges represented by him isnot only uncharitable from its language, but also basedon wrong premise.b. Pensionary benefits paid to the retired judges on the basisof judgment under challenge is past and closedtransaction and stare decisis, thus, no order for itsrecovery can be made even if the said judgment isreviewed and put at naught.c. Though the principle of stare decisis has very limitedapplication to the proceedings before the Supreme Court,being apex Court, but the rights and obligationsdetermined under any proceedings shall be considered asa past and closed transaction, which has created vestedrights under the judicial pronouncement in favour ofsome party.d. Suo moto exercise of jurisdiction in the presentproceedings in any form are not maintainable under thelaw as held in the cases of Asif Saeed v. Registrar Lahore(PLD 1999 Lahore 350), Nusrat Elahi v. Registrar, Lahore

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 32High Court (PLJ 1991 Lahore 471), Abdul RehmanAntulay v. Union of India (AIR 1984 SC 1358). In case thepresent proceedings are being entertained under Article184(3) of the Constitution, then no violation or breach ofany fundamental right of any citizen of this Country hasbeen urged, which is sine qua non for exercise of suchjurisdiction.e. Principle of res judicata is squarely applicable after lapseof five years of pronouncement of judgment in the caseunder consideration, as held in the cases of Abdul Jalil v.State of U.P. (AIR 1984 SC 882), Virundhunagar S.R.Mills v. Madras Govt. (AIR 1968SC 1196) andAmalgamated Coalfields v. Janapada Sabah (AIR 1964 SC1013).f. The honourable retired judges of the High Court receivedthe pensionary benefits on the basis of judgment underchallenge in good faith and the bonafide orders of theapex Court, therefore, question of its refund does notarise, even if the said judgment is reviewed or revisited.23. At the conclusion of his arguments, with reference to theplea of stare decisis, <strong>Mr</strong>. Sheikh also read some passage from thebook titled as “Fundamental Law of Pakistan” authored by <strong>Mr</strong>. A.K.Brohi, a prominent jurist of this country. In the context of past andclosed transaction, he also placed reliance upon the cases of MissAsma Jilani v. Government of the Punjab (PLD 1972 SC 139),Liaqat Hussain v. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 1999 SC 504),Jamat-i-Islami Pakistan versus Federation of Pakistan (PLD 2000SC 111).

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 3324. In the case of Miss Asma Jillani (supra), dealing with acriminal appeal wherein question arose, whether the High Courthad jurisdiction under Article 98 of the Constitution of Pakistan(1962) to enquire into the validity of detention under the MartialLaw Regulation No.78 of 1971 in view of the bar created by theprovisions of the Jurisdiction of Courts (Removal of Doubts) Order,1969 and the doctrine of law enunciated in the case of State versusDosso (PLD 1958 S.C. (Pak.) 533), the successive manoeuvrings forusurpation of power under the Pseudonym of Martial Law werejustified or valid, the Court while discussing various principles ofinterpretation of statutes held that: no duty is cast on the Courtsto enter upon purely academic exercise or to pronounce uponhypothetical questions: Courts’ judicial function; is to adjudicateupon real and present controversy formally raised before it by thelitigant; Court would not suo moto raise a question or decide it;doctrine of stare decisis is not inflexible in its application; lawcannot stand still nor can the Courts and Judges be made mereslaves of precedent. In this case finally upholding the doctrine ofnecessity it was further observed that the transactions which arepast and closed may not be disturbed as no useful purpose can beserved by reopening them.25. In the case of Sh. Liaqat Hussain (supra) reviewing thejurisdiction of the Apex Court under Article 184 (3) of theConstitution, it was held that law if validly enacted cannot bestruck down on the ground of malafide but the same can be struckdown on the ground that it was violative of Constitutionalprovision. Further with reference to Article 6 of the Constitution,application of doctrine of necessity was rejected. Moreover, theconcept of public importance within the meaning of Article 184 (3)

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 34of the Constitution was discussed in detail and it was held thatunder Article 9 of the Constitution right of access to justice to all isa fundamental right guaranteed to every citizen of the country.However, in the end this petition and other connected petitionsunder Article 184(3) of the Constitution, challenging the PakistanArmed Forces (Acting in Aid of the Civil Power) Ordinance 1998promulgated on 20 th November, 1998, thereby empowering theMilitary Courts to try civilians for civil offences, were dismissed inthe terms as detailed in the short order dated 17.2.1999.26. In the case of Jamat-i-Islami Pakistan (supra), it was heldthat a statute must be intelligibly expressed and reasonablydefinite and certain and it is the duty of the Court to find out thetrue meaning of a statute while interpreting the same. In the samecontext the underlining principle of doctrine of “ejusdem generis”was also enumerated. Finally it was held that where the wordsused in a statute are ambiguous and admit of two constructionsand one of them leads to a manifest absurdity or to a clear risk ofinjustice and the other leads to no such consequence, the secondinterpretation must be adopted. It may also be added here that theother cases referred to by the learned Sr. ASC in paragraph “d” and“e” relating to the subject of maintainability and res judicata arepremised on entirely different facts and circumstances, and thushave no relevancy or applicability to the present proceedings.27. <strong>Mr</strong>. Gulzarin Kiyani, learned Sr. ASC, who is representing<strong>Mr</strong>. Muhammad Muzammal Khan, J., another honourable retiredjudge of the High Court and beneficiary of the judgment underchallenge, in his arguments firstly made reference to C.M.ANo.801/2013, and gave relevant dates of appointment of <strong>Justice</strong><strong>Justice</strong> Muhammad Muzammal Khan as additional Judge and

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 35permanent Judge of the High Court and the date of his retirement,to show that admittedly before retirement he rendered actualservice as a judge of the High Court for a period of 04-years, 05-months and 27-days. In his further arguments, learned Sr. ASCfirmly disagreed with the submissions of many other learned ASCs,who earlier to him have argued the case, on the point ofmaintainability of this petition as well as about the interpretationof paragraphs-2 and 3 of Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of theConstitution. He contended that this Court, being the apex Court,has wide jurisdiction to exercise suo moto review powers and theprinciple of stare decisis is not application in this regard. To fortifyhis submissions in this regard, he placed reliance upon the case ofAbdul Ghaffar-Abdul Rehman v. Asghar Ali (PLD 1998 SC 363).28. Again, making reference to the language of paragraph-2 ofFifth Schedule to Article 205 of the Constitution, he stronglycontended that there is only one category of judges of the HighCourt i.e. “Every judge” mentioned in this paragraph, either read itseparately and independently or together with paragraph-3, whoseright to pension are to be determined by the President from time totime and until so determined, they are entitled to the privileges,allowances and rights, to which immediately before itscommencing day, the judges of the High Court were entitled. Forthis purpose, he also made reference to High Court Judges OrderNo.7 of 1937, President’s Order No.9 of 1970 and President’s OrderNo.3 of 1997, to show that even before partition of the subcontinent,the rights, qualifications and entitlement of the judgesof the High Court for the purpose of pension were being regularlydetermined, but at no point in time, any judge of the High Court

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 36who had served as such for a period of less than five years, wasever found eligible or entitled under any dispensation for paymentof pension. It is only for this reason that right from the prepartitiondays, till the decision by way of judgment underchallenge, no retired judge of the High Court was found entitled forpayment of pensionary benefits if he has served in the High Courtfor any period less than five years. He added that it looks strangeand ridiculous that in case such right to pension was everavailable to the retired judge of the High Court at any time duringthe last sixty years, still all of them, who were jurists in their ownrights and adjudicators of law at the highest level, could not dareto interpret such Constitutional provisions or President’s Ordersissued in furtherance thereof in their favour, so as to avail thebenefit of pension upon their retirement before completing actualservice of less than five years. He also argued that paragraphs-2and 3 of the Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of the Constitution are tobe read together and in conjunction with the President’s Ordersissued under the said constitutional mandate from time to timeand this scheme of law makes it clear beyond any shadow of doubtthat there is no entitlement to pension for a judge of the HighCourt, who has served as such for actual period of less than fiveyears.29. Reverting to the case of his own client, learned seniorASC read before us paragraph 14, 15, 16 and 29 of the President’sOrder No.3 of 1997, the definition clause (b) and (g) from paragraph-2, relating to ‘actual service’ and ‘service for pension’ respectively,relevant for determination of pensionary rights of a High CourtJudge, read with regulation No.423(b) of CSR, which in the firstplace provides automatic dispensation of deficiency upto six months

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 37and further visualizes, subject to fulfillment of other conditions, thediscretion for dispensation and relaxation of such period upto oneyear by the President. According to <strong>Mr</strong>. Kiyani, in such eventuality,by pressing into service these constitutional and sub-constitutionalprovisions of the law, having rendered service of four years, fivemonths and twenty-seven days, his client has become entitled forthe pensionary benefits, more so, as benefit of addition of another30 days service period to his credit in terms of definition clause (g)of President’s Order No. 3 of 1997 cannot be denied to him. He alsocited the two earlier referred cases of Secretary Finance Division v.Muhammad Zaman and Muhammad Aslam Khan v. ADBP.30. At the conclusion of his arguments, learned Sr. ASCsubmitted that in case the arguments advanced by him are notsustained and the judgment under challenge is reviewed/revisited,still the application of such judgment should be madeprospectively, so as to save the benefits, which his client hasalready availed in the form of pension etc on the basis of judgmentunder challenge.31. Raja Muhammad Ibrahim Satti, learned Sr. ASC,representing in these proceedings one honourable retired judge ofthe High Court, <strong>Mr</strong>. Mansoor Ahmed, J., also made reference ofC.M.A No.873/2013, which is a reply on his behalf. He providedrelevant details about the date of his appointment as additionaljudge of the High Court and the date of his retirement, whichshows his actual period of service as 03-years, 02-months and 04-days. Learned ASC in his arguments strongly challenged themaintainability of this review petition on account of the fact that ithas emanated from a note of the Registrar of the Supreme Court in

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 38this regard, who has no judicial or administrative jurisdiction orauthority at all to undertake such critical examination of an earlierjudgment of the Supreme Court, which has become final, followingthe doctrine of stare decisis, and become past and closedtransaction. He, however, in the same breath also candidlyconceded about the unbridled jurisdiction of this Court to correctany legal error and submitted that indeed where there is a wrongthere is a remedy is a well recognized principle of jurisprudence, soalso the fact that when superstructure is built on wrong legalfoundation, then upon its removal in any form, suchsuperstructure is bound to collapse. The learned counsel furtherplaced on record written formulations of his argument, which readas under:-“1. Whether the Registrar of this Court as defined in Order 1Rule 2(1) and has been assigned certain powers andfunctions under Rule 1 of Order III and also Under OrderV Rule 1, could in any way authorized or competent tomonitor, supervise, scrutinize or having a watch over theJudicial Function of the Court and particularly tocomment/point out legal flaws or defects in the judgmentsfinally passed by the Court or any Bench of the Court.2. Whether the Registrar who is Executive head of the Officehas any role to get reopen the Final judgments of thisCourt which have attained finality and if this course isadopted it will disturb whole the Scheme of Constitution.3. Whether even the note of Registrar is not misleading asapparently he based the note on total misconception asmentioned in para 5 of the Note that the judgment (PLD2008 SC 522) is based on PO.NO.8 of 2007 and thatPO.No.8 of 2007 has been declared void ab-initio in PLD2009 SC 879, in fact the judgment is otherwise and itmainly based on interpretations of Article 25, 205, 207(3)Schedule V of the Constitution read with PO 2 of 1993, PO3 of 1997 and reference has been made to PO 8/2007 injudgment which in fact removed the anomaly and Retiredjudges were entitled to pension even independent of P.ONo.8 of 2007 and the said judgment is valid for otherreasons as mentioned in judgment.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 394. What prompted the Registrar to put up a note on judicialside after lapse of almost four years of the passing ofjudgment which had attained finality.5. Whether it was not proper to place the matter before anappropriate Bench to proceed with the matter if at all itwas necessary whereas the Hon’ble Chief <strong>Justice</strong> hadhimself decided the fate of note that prima facie the notemake out case of examination and accordingly issuedNotices straightaway to the Retired Judges.6. Whether when a judgment is passed in regular jurisdictionunder Article 185 the same can be reopened by recourseto other jurisdictions under Article 184, 186 of theConstitution, Human Right Forum or even Suo Moto.7. Whether the judgment is also not sustainable onadditional ground qua discrimination amongst Judges ofSuperior Courts.8. Whether the retired Judge who never applied or party tothe judgment can suffer for the Act of Court throughwhich benefit is extended to them and at any rate recoverycould be made for no fault of them.9. Whether in any case the re-visitation of the judgmentwould be operative retrospectively or prospectively.10. What should be effects and consequences and way-outregarding inaction of President of Pakistan for notdetermining the pension according to the scheduleregarding the Judges of the High Court who had notcompleted five years as permanent service though he wasempowered under the Constitution to do so.”32. In addition to the above, he contended that in casepresent proceedings are deemed to be in exercise of powers ofreview conferred upon this Court under Article 188 of theConstitution, read with Order XXVI of the Supreme Court Rules,1980, in that eventuality the guiding principle for determining theparameters of review as laid down by this Court in the case ofAbdul Ghaffar - Abdul Rehman (supra) are to be strongly adheredto. Reiterating his stance on the point of maintainability of thispetition, he stated that in case the note of the Registrar is takenout of consideration and upon perusal of the judgment underchallenge this Court feels it appropriate to proceed further with

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 42or taken oath under the Oath of Office of (Judges)Order, 2000 (I of 2000), and ceased to hold theoffice of a Judge shall, for the purposes ofpensionary benefits only, be deemed to havecontinued to hold office under the Constitution tilltheir date of superannuation.”35. <strong>Mr</strong>s. Asma Jehangir, representing <strong>Justice</strong> TariqMehmood, honourable retired judge of the High Court and thewidow of late <strong>Justice</strong> Khiyar Khan, former Judge of the High Court,in her arguments firstly furnished relevant details about theircareer as a judge of the High Court, which reveal that the formerserved as a Judge of the High Court from 06.9.2000 to 6.4.2002i.e. 01-year, 07-months and 04-days, while the late husband oflatter, who was elevated as additional judge of the High Court on16.9.1990 and reached the age of superannuation on 18.11.1994,had served for 04-years and 03-days. Arguing the case, she firmlyquestioned the maintainability of the petition in the present formas according to her, note of the Registrar cannot be taken as suomoto review petition against the judgment under challenge beforethis Court. Rather, such conduct of the Registrar is to bedeprecated. She further argued that even if the discussion andobservations contained in the judgment under challange, withreference to Presidents Order No.8 of 2007, are totally discarded,still the said judgment on the basis of other sound reasons issustainable in law and not open to interference under the limitedscope of review. She further argued that in paragraph-2 of the FifthSchedule to Article 205 of the Constitution word “every judge” alsoincludes additional judges for the purpose of pensionary benefits.Lastly, supporting the judgment under challenge on the principleof stare decisis, she placed reliance upon the judgment in the case

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 43of Bengal Immunity Co. v. The State of Bihar (AIR 1955 SC 661),which, inter alia, lays down that:-“This Court has never committed itself to any rule orpolicy that it will not “bow to the lessons of experience and theforce of better reasoning” by overruling a mistaken precedent…….This is especially the case when the meaning of the Constitutionis at issue and a mistaken construction is one which cannot becorrected by legislative action. To give blind adherence to a rule orpolicy that no decision of this Court is to be overruled would beitself to overrule many decisions of the Court which do not acceptthat view.But the rule of ‘stare decisis’ embodies a wise policybecause it is often more important that a rule of law be settledthan that it be settled right. This is especially so where as here,congress is not without regulatory power…… The question then isnot whether an earlier decision should ever be overruled, butwhether a particular decision ought to be. And before overruling aprecedent in any case it is the duty of the court to make certainthat more harm will not be done in rejecting than in retaining arule of even dubious validity.”……………………………………….It would be seen that in this case the Court acted uponthe limitations which they have laid down in the course of theirdecisions, that reconsideration and overruling of a prior decisionis to be confined to cases where the prior decision ‘is manifestlywrong and’ its maintenance is productive of great public mischief.The second is the case in –‘G. Nkambule v. The King’, 1950 AC379 (Z37), where the Privy Council declined to follow its priordecision in – ‘Tuumahole Bereng v. R.’, 1949 AC 253 (X38). In thiscase, the Privy Council, while it reaffirmed the proposition that aprior decision upon a given set of facts ought not to be reopenedwithout the greatest hesitation, explained why they, in fact,differed from the previous one in the following passage:“From a perusal of the judgment in ‘Tumahole’s case’,(Z38), it is apparent that the history of the adoption andpromulgation of the various statutes and proclamations dealingwith the effect of the evidence of accomplices in South Africa wasonly partially put before the Board, and much material which hasnow been ascertained was not presented to their Lordships onthat occasion. The present case, therefore, is one in which freshfacts have been adduced which were not under considerationwhen Tumahole’s case (Z38) was decided, and accordingly it isone in which, in their Lordships’ view, they are justified inreconsidering the foundations on which that case wasdetermined”.

Const. Petition No.127 of 2012 44……… It will be noticed that the overruling of the priordecision in this case was based on the fact that important andrelevant material was not placed before the Judicial Committee inthe earlier case. These cases emphasis under what exceptionalcircumstances a prior decision or the highest and final court in acountry is treated as not binding on itself.”36. <strong>Mr</strong>. Sadiq Leghari, another honourable retired judge ofthe High Court, who appeared in person, invited our attention toC.M.A No.686/2013, which is his reply to this petition. He gaverelevant details of his appointment as a judge of the High Courtbefore having served the District judiciary in Sindh for a period ofover thirty years to show that his actual period of service as judgeof the High Court is 03-years, 10-months and 04-days. He madereference to the operative part of the judgment under challenge toshow that by this judgment, no unrestricted or open ended reliefhas been granted to the retired judges of the High Court, but onlyto those retired judges of the High Court, who have retired in termsof Article 195 of the Constitution. As per his formulations, para 33of the judgment under challenge excludes the additional judges ofthe High Court from availing its benefit. He, while makingreference to Article 188 of the Constitution, candidly stated thatvast powers of review are available with this Court, which areaimed to foster the cause of justice and to undo any injustice orirregularity, legal or factual. <strong>Mr</strong>. Leghari also made reference to thejudgment in the case of Muhammad Mubeen-us-Salam v.Federation of Pakistan (PLD 2006 SC 602) to fortify hissubmissions that benefit of judgment under challenge oncereceived by him and other retired judges of the High Court hascreated a vested right in their favour and now it is a past andclosed transaction, which can not be reopened; more over, the twoparts of Fifth Schedule to Article 205 of the Constitution, relating