of Psilocybe - Mycophilia

of Psilocybe - Mycophilia

of Psilocybe - Mycophilia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

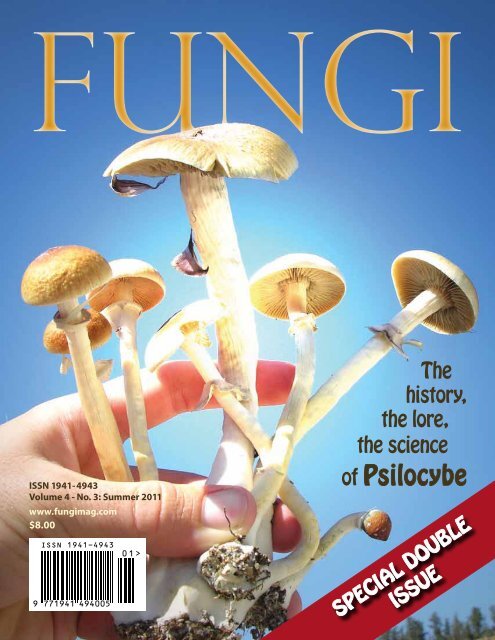

C alendar2011 MushroamingTibetan ToursJuly 31–Aug 13, 2011Summer Fungal & Floral ForaySee ad in this issue orinfo@mushroaming.com.2011 Eagle Hill and HumboldtInstitute Seminars & WorkshopsSteuben, MaineFor information seewww.eaglehill.us/programs/nhs/nhs-calendar.shtml.79th Mycological Society <strong>of</strong>America Annual MeetingUniversity <strong>of</strong> Alaska,Fairbanks, AKAugust 1–6, 2011For information seehttp://msafungi.org/.51st Annual NAMA ForayClarion, PAAugust 4–7, 2011Hosted by the Western PennsylvaniaMushroom Club.For information seewww.namyco.org.35th Annual NEMF Foray:The Samuel Ristich ForayPaul Smith’s College,Paul Smith’s, NYAugust 11–14, 2011For information, seewww.nemf.org.31st Annual Telluride MushroomFestivalTelluride, COAugust 18–21, 2011For information, seewww.tellurideinstitute.orgor this issue <strong>of</strong> FUNGI.2011 Foray Newfoundlandand LabradorTerra Nova National Park,Newfoundland, CanadaSeptember 9–11, 2011For information, seewww.nlmushrooms.ca.7th International Congresson Systematics & Ecology <strong>of</strong>Myxomycetes (ICSEM7)Federal University <strong>of</strong> Pernambuco,Recife, BrazilSeptember 10–17, 2011The congress will feature minicourses,posters, and PowerPointpresentations on topics relatedto the systematics and ecology <strong>of</strong>Myxomycetes and Protostelids. Awebsite will be available in the nearfuture. Please direct inquiries to:icsem7@gmail.com.7th Annual Sicamous FungiFestivalSicamous, BC, CanadaSeptember 18–25, 2011For information, seewww.fungifestival.com.10th AnnualTexas Mushroom FestivalMadisonville, TXOctober 21–22, 2011Gala dinner Friday; Festival onSaturday. This is a big one, folks,more than 15,000 attended in2010! For information, see www.texasmushroomfestival.com orfuture issues <strong>of</strong> FUNGI.25th Annual BreitenbushMushroom GatheringDetroit, OROctober 20–23, 2011For information, contactpatrice@mushroominc.org or www.mushroominc.orgor see ad in this issue <strong>of</strong> FUNGI.On the cover: Original photoby R. White with creativeenhancement by T. Orin Moshier.C ontents2461820243141434548495161646668Editor’s Letter, Britt BunyardLetters to the EditorThe Genus <strong>Psilocybe</strong>in North America,Michael W. BeugThe Legal Status <strong>of</strong>Psilocybin or PsilocinContaining Fungi,Jack SilverPsilocybin – Its Use andMeaning, Gary Linc<strong>of</strong>fNotes from Underground,David RosePsilocybin – History,Michael W. BeugMagic Mushrooms andAllowed Use Abroad,William Harrison<strong>Psilocybe</strong> 101, Britt Bunyard,Photos by P. Stamets, M. Beug,A. Rockefeller & J.HutchinsFamily Trees: A Mycolegium<strong>of</strong> Fungal Literature,Else C. VellingaForay: 2010 Fungi Festival atSicamous, BC, Kora Page SauterWhat Mushrooms Have TaughtMe About the Meaning <strong>of</strong> Life,Nicholas P. MoneySwedish Mushrooms,Maria JönssonMysterious Asian Beauty,J. Ginns & Lawrence MillmanThe Wild Epicure,Albert J. CascieroBookshelf FungiAdvertiser ListingFUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 20111

etters to The EditorLBlue staining <strong>Psilocybe</strong>s lookinggreat on a blue background. Photosent anonymously.Ienjoyed reading Denis Benjamin’ssatirical article on Amanita muscariain the Winter 2011 issue <strong>of</strong> FUNGI(vol. 4, no. 1). I especially appreciatedhis enumeration <strong>of</strong> five different waysthat one can die after eating Amanitamuscaria. Unfortunately, he missedone important potential cause <strong>of</strong> death.Consuming the mushroom outdoors incold weather can and has led to deathfrom hypothermia while in a deep comalikesleep. Since the deep coma-like sleepis a common occurrence after eatingAmanita muscaria, the dangers <strong>of</strong> eatingthis mushroom in cold weather shouldnot be underestimated.Thus there are six modes <strong>of</strong> lethalityinvolving Amanita muscaria, not justfive and precisely half <strong>of</strong> the modes <strong>of</strong>lethality do not involve the helping hand<strong>of</strong> the police. Furthermore, all <strong>of</strong> themodes <strong>of</strong> lethality except for gluttonyapply to the mind-altering mushroomscontaining psilocybin and psilocin. Itappears that there is no lethal upper limitto the amount <strong>of</strong> psilocybin and psilocinyou can consume and thus gluttony isnot a problem with <strong>Psilocybe</strong>s. However,while under the influence <strong>of</strong> psilocybinmushrooms, you may encounter policewho may shoot you, Taser® you orsuffocate you using a restraint hold.You may instead suffocate yourself bychoking on your vomit. Finally, youmay die <strong>of</strong> hypothermia if you consumepsilocybin mushrooms out <strong>of</strong> doors incold weather. The hypothermia threatcomes not from a deep coma-like sleep,but from a complete loss <strong>of</strong> control<strong>of</strong> your limbs. Thus you can have theprivilege <strong>of</strong> being initially conscious asyou freeze to death, unable to get yourlimbs functioning to get you to safety.Finally, while it has not been reportedwith Amanita muscaria, there has beenmore than one death from anaphylacticshock after consuming <strong>Psilocybe</strong>mushrooms. Thus both groups providesix ways to die.There is a serious problem withAmanita muscaria as a potentialinebriant. Based on my review <strong>of</strong>hundreds <strong>of</strong> ingestion cases, I find that innearly half <strong>of</strong> the reports I have received,there is no mention <strong>of</strong> any extraordinaryvisions. The person who has ingestedthe mushroom <strong>of</strong>ten goes straight tothe vomiting and diarrhea and then intothe deep coma-like sleep. There is notemporary chemical vacation, at leastthat he or she can remember. They dovividly remember the size <strong>of</strong> the hospitalbill, assuming that they are unfortunateenough to have been hospitalized. Isay unfortunate because they wouldgenerally survive the experience just fineon their own, assuming that they do notgo berserk and run afoul <strong>of</strong> the police ordie <strong>of</strong> hypothermia or inhalation <strong>of</strong> theirvomitus.Finally, I have to take issue with DenisBenjamin’s proposal for serving peopleproperly cooked Amanita muscaria.While I have not tried the recentlyfamous method <strong>of</strong> detoxifying cookedAmanita muscaria myself, I have talkedto numerous people who have. Theyhave all reported that the properlycooked mushrooms were rather soggyand bland. One can hardly make any realrevenue running a restaurant cookingsoggy, bland food. The analogy to fugu(blowfish) restaurants simply doesn’twork for me. What we need to do is totrain chefs to properly prepare and serveraw Amanita muscaria, because thathas both good flavor and good texture.Also, like fugu, there is a way to removemost, but not all, <strong>of</strong> the toxin. After all,the excitement <strong>of</strong> eating fugu is thatthe chefs leave some <strong>of</strong> the toxin in theblowfish, not enough to paralyze you,but just enough to give the diner a goodtingling sensation. I know how to do asimilar thing with Amanita muscaria.But, as Denis so wisely advised in hisarticle, I plan to keep my method secretso that I can pr<strong>of</strong>it from giving trainingcourses to the many chefs who I amcertain will rush forward to learn mysecret technique.Michael W. BeugPr<strong>of</strong>essor Emeritus,The Evergreen State CollegeP.O. Box 116Husum, WA 98623beugm@evergreen,ed“Should the harvesting and selling <strong>of</strong>wild mushrooms be regulated?”The real reason I’m writing is toask if I can copy and distribute to a fewpeople, Denis Benjamin’s article, “Shouldthe harvesting and selling <strong>of</strong> wildmushrooms be regulated?” This takesan interesting point <strong>of</strong> view (not to<strong>of</strong>ar from my own). I’d like to distributeit to a few <strong>of</strong> the members on a statesubcommittee investigating this veryquestion in Washington.Fred RhoadesPuget Sound Mycological SocietyWe got many requests for copies<strong>of</strong> this article by Denis Benjamin. Ifanyone else is interested, please visitthe FUNGI website where you will finda downloadable / printable version<strong>of</strong> Denis’s paper. Please feel free todistribute.-Ed.Spring FUNGI, minor error andcommentTo the Editor:It puts a smile on my face when iextract a new issue <strong>of</strong> fuNGi from mymailbox. it was great to see the picturethat Glen Schwartz took in “UnusualSightings” for the spring issue (vol. 4,no. 2). one minor correction: We arethe Prairie States Mushroom Club notMycological Society.There was a mention <strong>of</strong> taking photosthrough a stereo microscope in thepiece about the German publicationDer Tintling. i think the idea washatched by birders a decade ago takingpictures through a spotting scope—agreat way to capture and documentrare or unusual bird sightings. But whylimit it to a stereo microscope? i’vetaken shots through my compoundmicroscope with good success. Aninexpensive point and shoot is a greattool to document everything frommacro to micro. i took these images(pictured) with an “old” Canon 520Awith 4 megapixel. A slime moldthrough Dean Abel’s stereo scope andthe other <strong>of</strong> a section taken from anEyelash Cup through my compoundscope at 400X. i went the extra stepand turned a wooden sleeve on mylathe with some concentric bores; oneto match the eyepiece diameter and theother to match the camera lens barreldiameter. There is also a step to spacethe camera as i have “high eyepoint”eyepieces. Helps with the alignment <strong>of</strong>the optics. i first focus the microscopeand then let the camera auto focus. Sosimple!Roger HeidtPrairie States Mushroom ClubIhave been collectingand drying a local<strong>Psilocybe</strong> speciesfor several years. (Inow have plenty <strong>of</strong>them dried in mycupboard, although Ihave heard that theylose their potency withtime.) Well, I finally gotaround to trying those<strong>Psilocybe</strong>s; cooked upa few mushrooms afterdinner last night. Noeffect after 45 minutesso I cooked up anotherfew mushrooms. Thatworked! It was a very,very nice evening.Haven’t laughed somuch in a very, verylong time. The viewfrom my terrace wasrather amazing! Allkinds <strong>of</strong> colors and myroom first got largethen it got small…But what was reallyamazing was that I feltno knee pain and lowerback pain for the firsttime in several years!To go on a mushroomwalk or just aboutany walking I need major pain killers(opiates). Lots <strong>of</strong> them and then I stillfeel pain when I walk. It was such aliberating experience last night. I wasactually dancing around. I haven’t readvery much <strong>of</strong> the literature regardingpsilocybin and pain. Is this a commonexperience?Name withheld,New York CityGary Linc<strong>of</strong>f responds: The mushroomin question, above (pictured, right), is<strong>Psilocybe</strong> “subaeruginascens,” whichmay actually be a recently describedspecies, <strong>Psilocybe</strong> ovoideocystidiata.It’s not uncommon around here. Thewriter has been gathering and drying itfor a few years. This letter is importantbecause the writer is not a drug user.He drinks alcohol. Period. The painrelief he experienced is importanthere, <strong>of</strong> course. I think we’re on theedge <strong>of</strong> discovering a decidedly useful,socially approved, function <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>mushrooms. It’s still at an anecdotalstage, but the evidence, such as it is, ismounting.Since this was an unsolicitedtestimonial from a naïve user – onewho knew nothing <strong>of</strong> the on-goingliterature on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>to control or reduce, even if onlytemporarily, pain that is otherwiseuntouched by standard medications– I think it deserves a place whereit can be seen. I’ve heard conflictingreports about the value <strong>of</strong> psilocybinuse for controlling the onset <strong>of</strong> clusterheadaches or reducing their pain,but this is another example <strong>of</strong> usingpsilocybin – and deserves moreattention. It might result in nothingnew down the line, but we have t<strong>of</strong>ollow it down that line to know forsure. If I were in the kind <strong>of</strong> paindescribed in the letter, I’d be usingpsilocybin every time I go mushroomhunting. (I know some people probablythink I’m ON psilocybin when I’m outmushroom hunting. I don’t go out <strong>of</strong> myway to disabuse them <strong>of</strong> that idea.)Cheers, GaryPhotos courtesy G. Linc<strong>of</strong>f4 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 5

The Genus <strong>Psilocybe</strong> in North Americaby Michael W. BeugPr<strong>of</strong>essor Emeritus, The Evergreen State College. P. O. Box 116, Husum, WA 98623, beugm@evergreen.eduThe genus <strong>Psilocybe</strong> is rathersmall, composed <strong>of</strong> mostlylittle brown non-descriptsaprobic mushrooms that no one wouldnormally give a second thought toexcept for the presence in some <strong>of</strong> apair <strong>of</strong> very special indoles. <strong>Psilocybe</strong>was until fairly recently thought tobe closely related to Stropharia andseveral members, including <strong>Psilocybe</strong>cubensis, have been moved back andforth between the two genera. However,current interpretation <strong>of</strong> DNA resultsshows that the <strong>Psilocybe</strong> genus iscaused considerable consternationwith taxonomists because it meansthat whatever species are related to thetype species for the genus will retainthe name <strong>Psilocybe</strong> and the unrelatedspecies will have to go into a newgenus. The accepted type for <strong>Psilocybe</strong>,at least as i understood the situation,was a small non-descript mossinhabitingspecies, <strong>Psilocybe</strong> montana(Pers.) P. Kumm 1871, that does notproduce psilocybin or psilocin (Fig. 1).That appeared to mean that all <strong>of</strong> thehallucinogenic mushrooms commonlyFigure 2. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceataIn the 1970s and 1980s when PaulStamets, Jeremy Bigwood and Iwere doing our research on thechemistry <strong>of</strong> these mushrooms andnaming a new species and new variety,the large <strong>Psilocybe</strong> species (similar insize to Agaricus campestris or to thestore-bought button mushrooms) wereconsidered by some authors to belongin the genus Stropharia. Of these larger,meaty species there is one species <strong>of</strong>particular interest due to the presence<strong>of</strong> psilocybin and psilocin. That speciesis <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis Earle (Singer) (Fig.3). It is a beautiful mushroom reachingFigure 3. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensisup to 8 cm across. The cap can startout with an umbo and becomes firstbell-shaped and then convex as it ages.The cap is biscuit brown fading to paletan as it dries out and has tiny whitishscales. There is a partial veil leaving adistinct ring on the <strong>of</strong>f-white stipe. Allparts bruise blue. In the United Statesit is found in the wild throughout theSoutheast and in Texas and Hawaii. Itis common in Mexico. Its habitat is onwell-manured ground and on dung –and that can be the dung <strong>of</strong> cattle, oxen,yaks, water buffalo, horses or elephants.This is a truly widespread tropicalspecies fruiting spring, summer and fall.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> subcubensis is a highly similartropical species and though reportedFigure 1. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> montanacomprised <strong>of</strong> two groups that are onlydistantly related to each other andboth groups are only distantly relatedto Stropharia. one group <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>species produces the hallucinogenpsilocybin (and usually also the closelyrelated hallucinogen psilocin) and theother group does not. Both groupscurrently in the genus <strong>Psilocybe</strong> areactually much more closely related toHypholoma and Pholiota than they areto Stropharia.The news that <strong>Psilocybe</strong> was composed<strong>of</strong> two only distantly related groupsknown as psilocybes (sometimes simply“‘shrooms”) were going to need a newgenus.Fortunately a well-respected group<strong>of</strong> mycologists (Redhead et al., 2007)came to the rescue with a proposal toconserve the name <strong>Psilocybe</strong> with aconserved type. As <strong>of</strong> february 2010(Norvel, 2010), it was <strong>of</strong>ficial – thegenus <strong>Psilocybe</strong> was conserved with<strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceata (Fr.) P. Kumm1871 as the conserved type (Fig. 2).<strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceata is one <strong>of</strong> thehallucinogenic <strong>Psilocybe</strong> species, anda very potent one at that, averagingaround 1% by dry weight psilocybin,but more about that later. Whatwill happen to the nomenclature <strong>of</strong><strong>Psilocybe</strong> montana and its relatives isa story yet to be told, and one aboutwhich few will care.Most species <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>,hallucinogenic or not, are small andthin fleshed. All are saprobic – someon dung, some on woody debris, someon other plant remains, some on soiland others among mosses. The capis smooth, <strong>of</strong>ten a bit viscid (slimy),sometimes with a few small appressedsquamules (small scales) or veilremnants, colored whitish, ochraceous,grayish, buff, brown or red-brown,<strong>of</strong>ten hygrophanous (the color lightensto pale tan as the cap loses moisture,<strong>of</strong>ten starting in the center). Most <strong>of</strong>the hallucinogenic species bruise fromslightly blue to intensely blue-black.The spore prints are usually dark violetbrown but in some non-hallucinogenicspecies can be reddish brown orochraceous. Microscopically the sporesare smooth, rather thick-walled, witha germ pore. Cheilocystidia occur ina range <strong>of</strong> shapes but pleurocystidiaare usually lacking and chrysocystidiaare absent. There are about 30 speciesin the united States and Canada andan additional 50+ species in Mexico– with some <strong>of</strong> the Mexican speciesappearing in florida and other tropicalto subtropical parts <strong>of</strong> the united States(Guzmán, 2008).Breitenbush MushroomGatheringOctober 20-23, 2011Eastern European Mushroom TraditionsAlexander Viazmensky, mushroom artist fromSt. Petersburg will teach watercolor paintingChef Michasia Pawluskiewicz will lead themushroom culinary workshopFeatured Speakers: Dr. Denis Benjamin, Daniel Winkler,Debbie ViessCost: $175 plus lodgingRegistration: Breitenbush 503.854.3320Info: patrice@mushroominc.org 206.819.4842www.mushroominc.org6 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 7

from California, it was probably theresult <strong>of</strong> an outdoor growing operation(Stamets, 1996). I have even found<strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis outdoors in thesummer near Olympia, Washington,but again it was undoubtedly the briefresult <strong>of</strong> someone having planted aspawn bed there. For illicit cultivators,<strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis is generally themushroom <strong>of</strong> choice since it is easy togrow and produces a significant amount<strong>of</strong> biomass with each flush (Stamets andChilton, 1983).Jeremy Bigwood and I devotedconsiderable effort to trying tounderstand when the indoles psilocybinand psilocin were produced, if thechemicals <strong>of</strong> interest were concentratedin any one part <strong>of</strong> the mushroom, andwhether or not there was much variationfrom one stain <strong>of</strong> this species to another(Bigwood and Beug, 1982). Jeremy had aphenomenal knack for obtaining streetsamples <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis and ascoauthor (under a pseudonym) <strong>of</strong> anearly cultivation guide (Oss and Oeric,1976) had considerable cultivationexperience as well. His connections withleading DEA authorities smoothed theway for approval <strong>of</strong> my drug researchapplication.Our finding with <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensiswas that the chemicals psilocybinand psilocin were reasonably evenlydistributed throughout the mushrooms.With the exceptionally potent Peruvianstrain we were working with, the levelsvaried by a factor <strong>of</strong> four from onegrowing session to another growingsession and even from one flush to thenext. <strong>of</strong> even more concern was theobservation that in collections fromthe street, levels varied by a factor <strong>of</strong>10 from one collection to the next.We found levels <strong>of</strong> psilocybin pluspsilocin combined varying from 0.1%by dry weight up to 0.6-0.8%, even astaggering 1.4% in one case from ourespecially potent cultivated strain.Individuals who choose to ignore thesteep penalties for use <strong>of</strong> psilocybinor psilocin (it is a Class i Drug, withpossession treated similar to possession<strong>of</strong> heroin or cocaine), and choose touse this mushroom do not have anypractical way <strong>of</strong> knowing how strong theeffects <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis are likelyto be. While it is a good presumptionthat cultivated material will have about0.5% active material by dry weight andmaterial collected in the wild will haveabout 0.2 to 0.3% active material, manycollections will be much less potent anda few collections will be twice as potentas one might have assumed.Figures 4 (above) & 5a (below). Twowatercolors <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescensby Roger Heim<strong>Psilocybe</strong> weilii Guzmán, Tapia &Stamets is a medium (2-6 cm broad)semitropical species so far reported onlyfrom Georgia where it is found on redclay soil near both loblolly pine (Pinustaeda) and sweetgum (Liquidambarstyraciflua). <strong>Psilocybe</strong> weilii has capswith an inrolled corrugated marginreminiscent <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> baeocystis.The bluing reaction is very strong andthe psilocybin plus psilocin contentis nearly 0.9 % with 0.05% baeocystinand some tryptophan present as well.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescens Murrill is anotherspecies that seems to prefer disturbedor cultivated ground <strong>of</strong>ten withoutherbaceous plants present. <strong>Psilocybe</strong>caerulescens Murrill can also be foundon sugar cane residues and tends togrow in clusters. While it was firstfound in Montgomery, Alabama, it iscurrently only known from MexicoFigure 6. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> hoogshageniiis the illustration labeled<strong>Psilocybe</strong> zapotecorum in anotherwatercolor by Roger Heimwhere it is most commonly found onmuddy orangish brown soils. <strong>Psilocybe</strong>caerulescens is quite potent and is themushroom that R. Gordon Wassonconsumed in Mexico, as reported in afamous Life magazine article (Wasson,1957). Watercolor illustrations <strong>of</strong> twovarieties <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescens(Figures 4 and 5a) appeared in thatfamous Life magazine article. Thewatercolors were all done by RogerHeim, a French mycologist whoaccompanied Wasson on some <strong>of</strong> hisexploration trips to Mexico.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> hoogshagenii Heim sensulato (= <strong>Psilocybe</strong> zapotecorum Heimsensu Singer) also grows in muddyclay soils <strong>of</strong> Mexico, but very far southin subtropical c<strong>of</strong>fee plantations.Specimens from Brazil were found tocontain 0.6% combined psilocybin pluspsilocin (Stijve and de Meijer, 1993).It can fruit in massive abundance inthe c<strong>of</strong>fee plantations <strong>of</strong> Central andSouth America. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> hoogshageniiis the illustration labeled <strong>Psilocybe</strong>zapotecorum (Figure 6) in the Lifemagazine article (Wasson, 1957).Confusingly, <strong>Psilocybe</strong> zapotecorumHeim emend Guzmán is also ahallucinogenic species found in c<strong>of</strong>feeplantations as well as in marshydeciduous forests. However, <strong>Psilocybe</strong>zapotecorum Heim emend Guzmán doesnot look much like the mushroom withthat name illustrated in the Life magazinearticle but instead looks much like<strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescens var. mazatecorum(Figure 5a), and indeed is frequentlyconfused with <strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescens(Stamets, 1996). <strong>Psilocybe</strong> zapotecorumis one <strong>of</strong> the most prized <strong>of</strong> thehallucinogenic mushrooms <strong>of</strong> Mexicoas it can be up to 1.3% psilocybin pluspsilocin (Stijve and de Meijer, 1993). It isFigure 5b. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescensvar. mazatecorum. Photo courtesy<strong>of</strong> A. Rockefeller.typically cespitose to gregarious, rarelyscattered and like many <strong>of</strong> the Mexican<strong>Psilocybe</strong> species, it is frequently foundin steep ravines on exposed soils. Itsappearance is reminiscent <strong>of</strong> a large<strong>Psilocybe</strong> caerulescens var. mazatecorumthat is particularly convoluted and withan asymmetrical cap (see Figure 5band additional photos elsewhere in thisissue). <strong>Psilocybe</strong> muliericula Singer andSmith is another bluing Mexican speciesfound on muddy or swampy soils.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> muliericula is found in the state<strong>of</strong> Mexico under Abies and Pinus. TheFrench mycologist Heim had planned toname this species <strong>Psilocybe</strong> wassonii butRolf Singer and Alex Smith, using Heimand Wasson’s contacts, published theirname 24 days ahead <strong>of</strong> Heim’s plannedpublication (Stamets, 1996). I came to bevery aware <strong>of</strong> the resultant rift betweenWasson and Smith because Alex Smithcollaborated with Paul Stamets. Alexwas enamored <strong>of</strong> the spectacularScanning Electron Microscope imagesthat Paul was taking at The EvergreenState College. Another <strong>of</strong> my students,Jonathan Ott, became a close associate <strong>of</strong>R. Gordon Wasson.Two <strong>of</strong> the Mexican <strong>Psilocybe</strong> speciesare characterized by having a longpseudorhiza – a root-like extension <strong>of</strong>the stipe going into the ground. one<strong>of</strong> these species is the rare <strong>Psilocybe</strong>wassoniorum Guzmán and Pollock,named in honor <strong>of</strong> R. Gordon Wassonand his wife Valentina. <strong>Psilocybe</strong>wassoniorum is found solitary or insmall groupsin subtropicaldeciduous forests.It is known to beactive but is <strong>of</strong>unknown potency.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> herreraeGuzmán has anextremely longstipe and a verylong pseudorhiza.<strong>Psilocybe</strong> herreraeis moderatelyactive. it isfound in Chiapasand Veracruz,Mexico solitary togregarious in openforests <strong>of</strong> pines,sweetgums, andoaks.In Florida andpossibly otherparts <strong>of</strong> theSoutheast, some<strong>of</strong> the Mexican<strong>Psilocybe</strong> speciesare sometimesencountered butexactly which species can be foundthere is still somewhat unclear as mostseekers <strong>of</strong> hallucinogenic species in thatregion seek out <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cubensis. Oneknown tropical species that is also foundin florida is <strong>Psilocybe</strong> mammillata(Murrill) Smith – the classical bluingreaction is a clue to the presence <strong>of</strong>psilocybin and psilocin, but the specieshas not been quantitatively analyzedand i know <strong>of</strong> no experimental use <strong>of</strong>this species. it is found in soils rich inwoody debris and sometimes on claysoils. <strong>Psilocybe</strong> tampanensis is foundin florida and Mississippi but is quiterare in the wild so its preferred habitatis unknown. it has become popular withcultivators (Stamets and Chilton, 1983).<strong>Psilocybe</strong> tampanensis has a cap that isonly 1 to 2.4 cm broad (less than 1”) anda slim stipe with the classical blue-blackspore print and bluing reaction. it cancontain up to 1% psilocybin and psilocinby dry weight.Some individuals have also beentempted to try some <strong>of</strong> the largetemperate <strong>Psilocybe</strong> species because<strong>of</strong> their more or less pronouncedblue-green coloration. One exampleis <strong>Psilocybe</strong> aeruginascens (Fig. 7). Inthe samples <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> aeruginascens8 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 9

altered habitats. Thesame appears to be truefor <strong>Psilocybe</strong> baeocystis,<strong>Psilocybe</strong> stuntzii and<strong>Psilocybe</strong> weilii.The combinedpsilocybin plus psilocincontent <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>azurescens was foundby J. Gartz (in Stamets,1996) to be over 2%with a staggering 0.35%baeocystin. The fleshcan become indigo blackfrom bruising. It is easilyone <strong>of</strong> the most potentmagic mushrooms inthe world. Frankly, thestaggering baeocystincontent is <strong>of</strong> concern to me. Years ago,Repke, who identified baeocystin inmany <strong>of</strong> these species, told me that hefelt that baeocystin produced strongerhallucinations than psilocin/psilocybin.But it, or something also produced bymushrooms producing baeocystin,also seems to produce stronger adversereactions and more cases <strong>of</strong> bad trips.The newest named <strong>Psilocybe</strong> in the<strong>Psilocybe</strong> cyanescens-complex is <strong>Psilocybe</strong>hopii Guzmán et J. Greene (Guzmán etFigure 23. “No mushroom picking” signal., 2010) found in a temperate forestin Arizona, a place not previouslyassociated with hallucinogenic <strong>Psilocybe</strong>species. It was found on black soils inan aspen (Populus tremuloides) forestwith douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) plusbracken ferns (Pteridium aquilinum)– and this makes it the only member<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Psilocybe</strong> cyanescens complex inNorth America so far found in its nativewoodland habitat, though since it canbe readily cultivated, it may soon beturning up in wood mulch in manynew areas. Microscopically <strong>Psilocybe</strong>hopii differs from other members <strong>of</strong>the P. cyanescens complex by havingspecial cheilocystidia (sterile cell on thegills) with long and sinuous necks. Allparts are strongly bluing and the odoris farinaceous. It was found in the SanFrancisco Peaks region, an area sacredto the Hopi people, though the Hopi arenot known to have used hallucinogenicmushrooms.In another paper I will discussthe historical use, recreational useand potential medical use <strong>of</strong> thesespecies. However, be aware <strong>of</strong> the legalsituation. Possession <strong>of</strong> psilocybin orpsilocin in any form is illegal. The lawdoes not name specific mushroomsbut worldwide, according to JohnAllen, a long time pursuer <strong>of</strong> thesespecies, there are over 150 psilocybincontaining mushrooms in many generaand families <strong>of</strong> gilled mushrooms(see http://www.mushroomjohn.org)and possession <strong>of</strong> any one <strong>of</strong> thesespecies can get you arrested. uniquely,their spores are <strong>of</strong>ten traded on theinternet. Since the spores have neverbeen shown to contain psilocybin orpsilocin, trading the spores is not illegal.However, growing the mushroomsfrom the spores produces psilocybinand psilocin and thus makes you a drugmanufacturer. i have been an expertwitness in a case where a mushroomcultivator was arrested (after beingturned in by a neighbor for suspiciousactivity) – fortunately for him the onlymushrooms he had fruiting were severalvarieties <strong>of</strong> the choice edible Pleurotusostreatus! i am on retainer now fora person arrested for possessing justspores – and spores <strong>of</strong> what i don’t yetknow. Whether the case ever will goto court or not is as yet unclear, but itis clear that the defense expenses arealready substantial for this individual. inanother case, years ago, i was an expertwitness where a dealer had been sellingto school children – except that themushrooms he was trying to sell werenot magic mushrooms! i never foundout whether or not the dealer thoughthe knew what he was doing or wassimply committing fraud on unwittingyoung people.In one notable event near tillamook,Oregon, i took a large group <strong>of</strong>prominent West Coast mycologists outinto a field to see if we could find anymagic mushrooms. They had never seenthem. i had obtained permission fromthe wife at the farmhouse, was licensedto possess and study these mushrooms,and still the farmer threatened toshoot us all and it was a VERY scaryencounter – and yet the farmer ignoredmany carloads <strong>of</strong> fisherman who haddriven across his field to fish for salmonin the river. We did not find anythingbut harmless cow-pie fungi in hisfield – that was before i knew to stickto boggy pastures if i wanted to find<strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceata. in anotherOregon incident, my oldest son wasonce stopped hours after photographing<strong>Psilocybe</strong> azurescens. He was miles awayfrom the spot, but his license was notedby a local and turned over to the police.Fortunately for him, he had not made avoucher collection and he had a copy <strong>of</strong>Paul Stamets’s Psilocybin Mushrooms<strong>of</strong> the World. He used that book to pointout that he was my son and was takingthe picture for me and thus escapedjailing (though i never did receive a copy<strong>of</strong> the picture). By the way, if you wantto collect <strong>Psilocybe</strong> mushrooms, youtoo should get a copy <strong>of</strong> Paul’s book.The descriptions and photos that i haveprovided here are certainly not enoughto go on if you want to collect thesespecies. if you are new to mushrooms,make certain to get your finds confirmedby a genuine expert. And unless youpotentially want to pay me $200/houras an expert witness in your trial, becareful to just look and not gather thesespecies at the wrong time or place. The“no mushroom picking” sign (Fig. 23)was not placed in the farmer’s field tokeep people from picking the MeadowMushrooms!REFERENCESBeug, M., and J. Bigwood. 1982.Psilocybin and psilocin levels in twentyspecies from seven genera <strong>of</strong> wildmushrooms in the Pacific Northwest,USA. Journal <strong>of</strong> Ethnopharmacology 5:271-285.Bigwood, J., and M. W. Beug. 1982.Variation <strong>of</strong> psilocybin and psilocinlevels with repeated flushes (harvests)<strong>of</strong> mature sporocarps <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong>cubensis (Earle) Singer. Journal <strong>of</strong>Ethnopharmacology 5: 287-291.Christiansen, A. L., K. E. Rasmussen,and K. Høiland. 1981. The content<strong>of</strong> psilocybin in Norwegian <strong>Psilocybe</strong>semilanceata. Planta Medica 42(7): 229-235.Gartz, J. 1994. Extraction and analysis<strong>of</strong> indole derivatives from fungalbiomass. Journal <strong>of</strong> Microbiology 34:17-22.Guzmán, G. 2008. Hallucinogenicmushrooms in Mexico: an overview.Economic Botany 62(3): 404-412.Guzmán, G., J. Greene, and F. Ramirez-Guillén. 2010. A new for scienceneurotropic species <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> (Fr.) P.Kumm. (Agaricomycetideae) from thewestern United States. InternationalJournal <strong>of</strong> Medicinal Mushrooms 12(2):201-204.Guzmán, G., F. Tapia, and P. Stamets.1997. A new bluing <strong>Psilocybe</strong> from USA.Mycotaxon 65: 191.Jokiranta, J., S. Mustola, E. Ohenoja,and M. M. Airaksinen. 1984. Psilocybinin Finnish <strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceata. PlantaMedica 50(3): 277-278.McCawley, E. L., R. E. Brummet,and G. W. Dana. 1962. Convulsionsfrom <strong>Psilocybe</strong> mushroom poisoning.Mushroaming inTibet&BeyondDetails at: www.MushRoaming.comOur “mushroaming” trips to Tibet are a once in a lifetime fungal, botanical andcultural experience in some <strong>of</strong> the most stunning landscapes on the planet. Tibetis not only endowed with an incomparably rich, ancient spiritual culture but alsoa long tradition in collecting, eating and trading mushrooms. Today, with unprecedenteddemand for caterpillar fungus (Cordyceps sinensis), matsutake and morels, Tibet hasthe highest fungal income per capita in the world. Of great importance are also boletes,Caesar’s, chanterelles, ganoderma, gypsies, wood ears and many other exotic species.We explore Tibetan forests, meadows, mountains and monasteries.Guided by Daniel Winkler and Tibetan local guides.Inquiries: info@mushroaming.comSummer Fungal & Floral Foray: July 31-Aug 13, 2011Mushroaming Ecuador & Bolivia: Jan / Feb 2012Cordyceps Expedition: June 2012Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Western PharmacologySociety 5: 27-33.Norvell, L. L. 2010. Conserved<strong>Psilocybe</strong> with <strong>Psilocybe</strong> semilanceata asthe conserved type. Taxon 59(1): 291-293.Oss, O. T., and O. N. Oeric. 1976.Psilocybin: Magic Mushrooms Grower’sGuide. Seattle: Homestead BookCompany.Redhead, Scott A., J-M. Moncalvo,R. Vilgalys, P. B. Matheny, L. Guzmán-Davalos, and G. Guzmán. 2007.Proposal to conserve the name <strong>Psilocybe</strong>(Basidiomycota) with a conserved type.Taxon 56(1): 255-257.Repke, D., D. Leslie, and G. Guzmán.1977. Baeocystin in <strong>Psilocybe</strong>, Conocybe,and Panaeolus. Lloydia 40: 566-578.Stamets, P. 1996. Psilocybin Mushrooms<strong>of</strong> the World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.Stamets, P., M. W. Beug, J. E. Bigwood,and G. Guzmán. 1980. A new species anda new variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psilocybe</strong> from NorthAmerica. Mycotaxon 11: 476-484.Stamets, P., and J. S. Chilton. 1983.The Mushroom Cultivator. Olympia:Agarikon Press.Stijve, T. C., and A. A. R. de Meijer.1993. Macromycetes from the state<strong>of</strong> Parana, Brazil. 4. The psychoactivespecies. Brazilian Archives <strong>of</strong> Biology andTechnology 36(2): 313-329.Stijve, T. C., and T. W. Kuyper. 1985.Occurrence <strong>of</strong> psilocybin in varioushigher fungi from several Europeancountries. Planta Medica 51(5): 385-387.Wasson, R. G. 1957. Seeking the MagicMushroom. Life May 13, 1957: 100-120.16 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 17

ABSTRACTThis article reviews the most recentlegal status <strong>of</strong> psilocybin and psilocinin the USA and select foreign countries.This article is not intended to constitutelegal advice. Persons on U.S. soil aregenerally subject to federal laws as wellas the laws <strong>of</strong> the state in which theyreside and/or do business concerningan activity within that state. Underfederal law psilocybin or psilocin areSchedule I drugs. Possession, sales,manufacturing and transportation areall prohibited. Spores do not containpsilocybin or psilocin and are thereforenot illegal under federal law, but canbe used as evidence <strong>of</strong> the intent tomanufacture. Fungi, at any stage and inany form, are not specifically prohibitedunless they contain psilocybin orpsilocin. The laws <strong>of</strong> each state vary.Generally, the states follow federal law.Three states, California, Georgia, andIdaho prohibit spores. In California,mere possession <strong>of</strong> spores is not illegal.It’s odd to think that walking in the woodsand stopping to pick a mushroom couldbe considered a criminal act. if themushroom you pick contains psilocybin itcould be.1 in Georgia you could be guilty <strong>of</strong>possessing a “dangerous drug” by unwittinglypicking up spores on a stroll.Georgia Code - Crimes andOffenses - Title 16 § 16-13-71(b) in addition to subsection (a) <strong>of</strong>this Code section, a “dangerous drug”means any other drug or substance declaredby the General Assembly to be a dangerousdrug; to include any <strong>of</strong> the followingdrugs, chemicals, or substances . . .(627)Mushroom spores which, when mature,contain either psilocybin or psilocin;Also considered “dangerous drug(s)”in Georgia are penicillin (694), sodiumthiosulfate (880.5); vitamin K (1035) andestrogenic substances (354)2. in a strictreading <strong>of</strong> Georgia law the possession <strong>of</strong>any soy product could be considered thepossession <strong>of</strong> a dangerous drug. Although,as Dickens observed, sometimes “the lawis a ass-a idiot.”3 ignorance <strong>of</strong> the law is nodefense to felony or misdemeanor charges.by Jack SilverA person on u.S. soil is generally subjectto federal laws as well as the laws <strong>of</strong> the statein which they reside and/or do businessconcerning an activity within that state.Under federal law psilocybin and psilocinare Schedule i drugs.4 Possession, sales,manufacturing and transportation are allprohibited. Spores do not contain psilocybinand are therefore not illegal under federal lawbut can be used as evidence <strong>of</strong> the intent tomanufacture. fungi, at any stage and in anyform, are not specifically prohibited unlessthey contain psilocybin. The laws <strong>of</strong> eachstate vary. Generally, the states follow federallaw. in other words, it is illegal to possess,sell, transport or manufacture a controlledsubstance. California, Georgia, idaho alsoprohibit spores even though the sporesthemselves do not contain any controlledsubstance.In California possession <strong>of</strong> spores in and<strong>of</strong> itself is not illegal. it is illegal to cultivate“any spores or mycelium capable <strong>of</strong> producingmushrooms or other material which containssuch a controlled substance” (CA Health& Safety Code § 11390). it is also illegal totransport, import, sell, furnish, give away, or<strong>of</strong>fer to transport, import, sell, furnish, orgive away “any spores or mycelium capable<strong>of</strong> producing mushrooms or other materialwhich contain a controlled substance” (CAHealth & Safety Code § 11391). So, if you arejust acquiring spore prints for a collectionwith no intention they be cultivated or usedto produce psilocybin containing mycelium orfungi you are not violating the law.CA Health & Safety Code§§ 11390-1139111390. Except as otherwise authorizedby law, every person who, with intent toproduce a controlled substance specifiedin paragraph (18) or (19) <strong>of</strong> subdivision(d) <strong>of</strong> Section 11054, cultivates anyspores or mycelium capable <strong>of</strong> producingmushrooms or other material whichcontains such a controlled substanceshall be punished by imprisonment in thecounty jail for a period <strong>of</strong> not more thanone year or in the state prison.11391. Except as otherwise authorizedby law, every person who transports,imports into this state, sells, furnishes,gives away, or <strong>of</strong>fers to transport, importinto this state, sell, furnish, or give awayany spores or mycelium capable <strong>of</strong>producing mushrooms or other materialwhich contain a controlled substancespecified in paragraph (18) or (19) <strong>of</strong>subdivision (d) <strong>of</strong> Section 11054 forthe purpose <strong>of</strong> facilitating a violation<strong>of</strong> Section 11390 shall be punished byimprisonment in the county jail for aperiod <strong>of</strong> not more than one year or inthe state prison.Generally the federal government is onlyinterested in crimes committed in areasunder federal jurisdiction such as post <strong>of</strong>fices,airports, federal land, federal buildings orlarge scale multi-state operations. using theU.S. Postal Service to transport controlledsubstances across state lines violates severalfederal laws as would transporting controlledsubstances into the u.S., including lying to afederal agent by going through customs andfailing to claim your substance.States vary not only state to state butregionally within a state. The reach <strong>of</strong> any lawis limited by the language which was enacted.If you are in the woods in California selecting<strong>Psilocybe</strong> spp. specimens for your spore printcollection you would not be violating the law.But in Georgia you might be.Most criminal laws require that prosecutorsprove scienter, that is, the defendants knewthey were violating the law.5 Thus in fiskev. State <strong>of</strong> florida, No. 50796, SupremeCourt <strong>of</strong> florida (1978), the court found thatpsilocybin mushrooms could not reasonablybe considered “containers” <strong>of</strong> the ScheduleI substance psilocybin. The court essentiallyheld that if the florida legislature wished tomake wild psilocybin mushrooms illegal, itwould have to name them in the law. Thecourt ruled: “the statute does not advise aperson <strong>of</strong> ordinary and common intelligencethat this substance is contained in a particularvariety <strong>of</strong> mushroom. The statute, therefore,may not be applied constitutionally to [thedefendant fiske who was caught with freshlypicked psilocybes].” The court did not addresswhether fiske would have been breakingthe law if the prosecution had proven fiskeknew the mushrooms contained psilocybin.Subsequent cases in other states have foundthe knowledge component to be the decidingfactor.In 2005 a New Mexico appeals courtruled that growing psilocybin mushroomsfor personal consumption could not beconsidered “manufacturing a controlledsubstance” under state law, State v. PrattNo. 24,387 (NM Court <strong>of</strong> Appeals 2005).Although Pratt was able to reverse the charge<strong>of</strong> manufacturing a controlled substance, hewas still convicted <strong>of</strong> possession.Therefore whether it is a crime to pickmushrooms containing psilocybin dependsupon where you are and the laws <strong>of</strong> thatjurisdiction.6,7Resources within state and local lawenforcement are allocated toward serious<strong>of</strong>fenses such as sales, transportation andmanufacturing before they are used to builda case for possession. Mushrooms containingpsilocybin are generally low priority for thefederal government and most state and locallaw enforcement prefer pursuing hard drugslike meth and heroin or popular targets suchas marijuana. Although the entheogenic orpsychedelic effect from psilocybin can be aspowerful as that from DMt or its cousin LSD,psilocybin is considered a mild intoxicant.8Worldwide, the legal status <strong>of</strong> psilocybinmushrooms varies.9 Psilocybin and psilocinare listed as Schedule i drugs under theUnited Nations 1971 Convention onPsychotropic Substances.10 However,psilocybin mushrooms themselves are notregulated by uN treaties. As a matter <strong>of</strong>international law, no plants (natural material)containing psilocin and psilocybin are atpresent controlled under the Conventionon Psychotropic Substances <strong>of</strong> 1971.Consequently, preparations made <strong>of</strong> theseplants are not under international controland, therefore, not subject <strong>of</strong> the articles <strong>of</strong>the 1971 Convention. uN recommendationsnotwithstanding, many countries have somelevel <strong>of</strong> regulation or prohibition <strong>of</strong> psilocybinmushrooms. Criminal cases regardingpsilocybin-containing fungi are decidedwith reference to the laws <strong>of</strong> the country orjurisdiction in which a person find themselves.Within national, state, and provincialjurisdictions there is a great deal <strong>of</strong>ambiguity as to the legal status <strong>of</strong> psilocybinmushrooms, as well as a strong element <strong>of</strong>selective enforcement. The legal status <strong>of</strong>spores is even more ambiguous, as sporescontain neither psilocybin nor psilocin, andhence are not illegal to sell or possess in manyjurisdictions, though these jurisdictions mayprosecute under broader laws prohibitingitems that are used in drug manufacturing.In some countries such as indonesia,trafficking in psilocybin can technicallycarry the death penalty. Though like mostjurisdictions, indonesia considers mushroomsa “s<strong>of</strong>t drug” and until recently allowedrestaurants in Bali to serve magic mushroomsmoothies and omelets. However, do notexpect other jurisdictions such as China,Singapore or the Middle Eastern countries tobe so forgiving.As mentioned above, psilocin andpsilocybin are controlled substances underSchedule 1 <strong>of</strong> the 1971 uN Convention onPsychotropic Substances, so all MemberStates control them accordingly. However,control <strong>of</strong> the mushrooms themselves isinterpreted in many different ways acrossEurope – this may reflect the extent to whichthey grow freely in certain conditions, andthe fact that they appear to be a somewhatregional phenomenon. A number <strong>of</strong> countriesremain with unclear legislation, simply asthere have been so few cases to reach thecourts.No matter where you are, the threshold forcharging someone with a crime is very lowcompared to the threshold for a conviction.As a general rule the knowing possession <strong>of</strong>psilocybin containing fungi in any stage orform is illegal in all jurisdictions within theU.S. and most outside the u.S. if a prosecutorwants to make an example <strong>of</strong> you the laws arethere to support the prosecution, requiring anexpensive defense.ABOUT THE AUTHORJack Silver is a mycophile and public interestattorney living in Sebastopol California.In addition to environmental law Jack hasdefended the First Amendment rights <strong>of</strong>individuals from groups like Critical Massand Food Not Bombs as well the right <strong>of</strong> theSanto Daime Church to use ayahuasca as asacrament.FOOTOTES1For simplicity, i refer to psilocybin andpsilocin as psilocybin.2Estrogenic substances also occur naturallyin cultivated plants, e.g. subterranean clover,and in fungi growing on plants and plantproducts, e.g. fusarium graminearum, f.roseum.3“That is no excuse,” replied Mr. Brownlow.“You were present on the occasion <strong>of</strong> thedestruction <strong>of</strong> these trinkets, and indeed arethe more guilty <strong>of</strong> the two, in the eye <strong>of</strong> thelaw; for the law supposes that your wife actsunder your direction.”“If the law supposes that,” said Mr. Bumble,squeezing his hat emphatically in both hands,“the law is a ass- a idiot. if that’s the eye <strong>of</strong>the law, the law is a bachelor; and the worstI wish the law is, that his eye may be openedby experience - by experience.” oliver twist,Charles Dickens.4The Controlled Substances Act (CSA)Pub. L. 91-513, 84 Stat. 1236, enacted october27, 1970, codified at 21 u.S.C. § 801 et. seq.The CSA is the federal u.S. drug policyunder which the manufacture, importation,possession, use and distribution <strong>of</strong> certainsubstances is regulated. The legislationcreated five Schedules (classifications),with varying qualifications for a substanceto be included in each. Schedule i drugsare classified as having a high potential forabuse; no currently accepted medical use intreatment in the united States and, a lack<strong>of</strong> accepted safety for use <strong>of</strong> the drug orother substance under medical supervision.Other Schedule i drugs include heroin andmarijuana. Cocaine and methamphetamine(“meth”) are Schedule ii drugs.5Generally in order to convict a person fora criminal felony, due process requires thata prosecutor prove the defendant knew hewas committing a crime. However, certaincrimes are strict liability requiring no scienter.In certain states statutory rape is a strictliability crime as is selling alcohol to a minor.Under federal law environmental crimes aregenerally strict liability.6An excellent text for identification isPsilocybin Mushrooms <strong>of</strong> the World by PaulStamets; ten Speed Press; 1996.7For a state by state list see North floridaShroom Guide’s mushroom law page www.jug-or-not.com/shroom/statelaw.html.8Based upon arrests compared toother substances including heroin,methamphetamine and cocaine.9For a comprehensive list <strong>of</strong> the laws invarious countries see European MonitoringCentre for Drugs and Drug Addiction(EMCDDA) http://www.emcdda.europa.eu//html.cfm//index17341EN.html?. AlsoEROWID has numerous references asto the legality <strong>of</strong> psilocybin containingmushrooms. See http://www.erowid.org/plants/mushrooms/mushrooms_law.shtmland related links.10See “List <strong>of</strong> psychotropic substancesunder international control” internationalNarcotics Control Board. August 2003. http://www.incb.org/pdf/e/list/green.pdf.18 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 19

So, can psilocybin save you from decades <strong>of</strong> therapy(at the cost <strong>of</strong> tens <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> dollars)? If it can,what “pr<strong>of</strong>ound psychological realignments” can youexpect to realize?Freud would probably say that thebest you could hope for would beto accept the “human condition,”that is, the general unhappiness <strong>of</strong> life.Other therapists would say some verydifferent things. Sandor Ferenczi mightsay that the human quest is to returnto the peaceful condition <strong>of</strong> the fetusbefore birth, before being thrust outinto the world. Other therapists, likeOtto Rank, might focus on the trauma<strong>of</strong> birth itself, well before the onset <strong>of</strong>early childhood issues, as the ultimatesource <strong>of</strong> our most disabling neuroses.One therapist, Stanislav Gr<strong>of</strong>, thinks thatunder the influence <strong>of</strong> a mind-alteringsubstance or a trance-induced state, onecan experience pr<strong>of</strong>ound encounterswith life before conception, prior lives,similar in a way, perhaps, to experiencingJung’s archetypes. The general consensus<strong>of</strong> those therapists not in the “Freudianschool” seems to be that the oceanicfeelings <strong>of</strong>ten associated with mindalteringsubstances, like psilocybin, is notso much a return to “life” in the amnioticfluid as it is the sense <strong>of</strong> connectednesswith all life, with all creatures, great andsmall, as well as all plants and all fungi.Is this sense <strong>of</strong> “oneness,” this strongfeeling <strong>of</strong> bonding with all sentient life,real or illusory, and in what sense? Canthe experience give us a window onto aworld otherwise denied us, or is it justby Gary Linc<strong>of</strong>fPrefaceIn a matter <strong>of</strong> hours, mind-altering substances may induce pr<strong>of</strong>ound psychological realignmentsthat can take decades to achieve on a therapist’s couchFrom “Hallucinogens as Medicine,” Roland Griffiths and Charles Grob,December 2010 issue <strong>of</strong> Scientific AmericanSit back, relax, take 5 mg and call me whenthe moon is in the seventh house and Jupiteraligns with Mars.a journey through the looking glass?Are metaphors inescapable here? “Ifthe doors <strong>of</strong> perception were cleansed,”would everything “appear to man as it is,infinite”?First, a few caveatsPsilocybin is a value-free, nonintegratedmolecular strategy fordeveloping cooperative individuals in thepursuit <strong>of</strong> social equality in a democraticsociety. This might sound like anoxymoron, if not outright moronic, and itis something that seems easier to disprovethan prove, but that doesn’t deter exercise<strong>of</strong> its use or prevent belief in its efficacy.Warning: If you are having an experience lasting morethan 4 hours, consult a shaman as soon as possible, iftime has any meaning for you.Psilocybin is not to be taken aloneor with your doppelganger (if you canrecognize him or her), or with totalstrangers (assuming you know a strangerwhen you see one). Taken with friendsit can lead to intense emotional bondingbetween individuals that others mayinterpret as totally inappropriate, andthat the affected couple finds nearlyimpossible to dissolve amicably.Psilocybin is not to be taken by thoseadherents <strong>of</strong> Freudian psychologywho believe that a feeling <strong>of</strong> “oceanicwholeness” is a symptom <strong>of</strong> infantileregression, and that this is something tobe eschewed.Psilocybin is not for those unpreparedto experience phylogenetic regression;the event, not manifested in physicalterms, as shown in the film Altered States,but capable <strong>of</strong> being described as clear,concrete, and accurate memories <strong>of</strong> a lifein the body <strong>of</strong> a different species.Psilocybin is not for people who displaya rigid personality or for those who fearloss <strong>of</strong> control; or, as Lily Tomlin hassaid, “reality is a crutch for those whocan’t handle drugs.” It might be truethat there are no atheists in a foxhole,as the saying goes, but an atheist highdosingpsilocybin will be unpreparedto experience God face to face, as itwere, and consequently will most likelymisinterpret the experience.Psilocybin is not for males who planto become pregnant; nor is it for malesattempting to breast-feed a baby.Psilocybin is not for femalesexperiencing acute penis envy or SDS(Sports Distraction Syndrome).The successful use <strong>of</strong> psilocybindepends in part on one’s set and setting.If you are in the wrong place at the wrongtime, or your expectations or thosearound you are creating stress, its use insuch situations cannot be recommended.Psilocybin is not the drug <strong>of</strong> choice toget you through rush-hour traffic or acolonoscopy.People taking psilocybin while on anMAO inhibitor medication can find theexperience more intense, perhaps toointense, and longer lasting, perhaps neverending. Who knew?So, who in their right mind, you mightask, would take psilocybin? Someone out<strong>of</strong> their (left) mind? Or, if you are findingyourself on planet Earth in the HumanChristian Earth-year <strong>of</strong> 2011, and arewondering who took the wrong turn, it’stoo late to check your genome. In thiscase, it might just be better to sit back,relax, take 5 mg and call me when themoon is in the seventh house and Jupiteraligns with Mars. Or, if you are wonderinghow the best minds <strong>of</strong> our generationgot wasted by the evening news, or howpeople who have reached the biblical age<strong>of</strong> three score years and ten, seem to bedisappearing before your very eyes, orare finding themselves with lots <strong>of</strong> bodyparts that aren’t the ones they were bornwith, or are entering the dark world <strong>of</strong>dementia, now may not be too soon todouble the dose.SOME CASE REPORTS:1 The YouTube clip from the movieKnow Your Mushrooms is essentiallytrue, at least as it was experienced. ifI learned anything from the event, itwas that there’s more to a psilocybinexperience than set and setting, since ididn’t know or trust the people i had metwho wanted me to share this mushroomwith them, and i wasn’t in the “mood”for having a non-dreaming out <strong>of</strong> bodyexperience; in fact, i was anxious to getto the airport on time and not miss myflight home. How naïve i was (and stillam) is beyond belief. Still and all, theexperience, as described on YouTubeand in the film was quite exhilarating.Whether it was an actual out-<strong>of</strong>-bodyexperience, or only an imagined one, itwas one that was intensely experienced.It was not spiritual in any normal sense<strong>of</strong> that term, although space travel doesseem to have a spiritual component.The only sense i could make <strong>of</strong> it wassome kind <strong>of</strong> attempt on my part toescape from wherever i was, which i didthanks to the light beam that i followedout to somewhere in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> theAndromeda galaxy. Was it the acting out<strong>of</strong> a birth trauma event, an escape from aliving “womb” that was no longer a placeI felt comfortable being in? Was my out<strong>of</strong>-bodyexperience a snake-like slitheringout <strong>of</strong> my “mortal coil,” an escape fromlife rather than an escape into life? Didit in some way change my life? Since iremember it so vividly, something thathappened so long ago, it must havechanged me in some way or other.2 I was in the Amazon with agroup on a ship exploring a few <strong>of</strong> itstributaries. We passed by a pastureand pulled in to see what mushroomsmight be coming up in the cow pies.We were ecstatic to find a blue-staining,black-spored mushroom, a species <strong>of</strong>Panaeolus, now called Copelandia. Weput a handful or two in a bowl with somefruit juice and mashed bananas. We hadno idea what its potency was. We calledthe mixture a blue banana smoothie.It wasn’t blue at all, but it tasted great.We became unusually quiet, quite oddfor a group <strong>of</strong> American eco-tourists(something we didn’t know we wereat the time). I lay in a hammock andbecame somewhat dreamy. A stormblew up out <strong>of</strong> nowhere. It suddenly gotquite dark and there was lightning andloud crashes <strong>of</strong> thunder. The ship’s crewlowered large, blue plastic sheets alongthe sides <strong>of</strong> the deck, to keep the rainfrom blowing in. I was immobilized inthe hammock, imagining myself in alifeboat. I remembered reaching underthe hammock and feeling all the holesbetween the interconnected strands <strong>of</strong>rope. Everything around me had becomedeep blue. Lightning would light up thescene and the blue plastic sheets floodedthe deck with its color. I was panicky. Itried to talk but couldn’t; words wouldn’tcome out <strong>of</strong> my mouth. I was overboardin a lifeboat full <strong>of</strong> holes. I was drowning.I was scared beyond belief. I must havepassed out because the next thing Iknew it was morning, the sun was out,the blue sheets had been raised, and Ihad not drowned in a leaky lifeboat. Theexperience, as horrific as it seemed atthe time, has become a mere cocktailcircuit anecdote. Many questions remainunanswered. For example, was thisexperience a pre-natal one, a sense <strong>of</strong>being mute and helpless in the womb atthe very moment <strong>of</strong> being pushed outinto the world? What, if anything, is tobe made <strong>of</strong> such an experience? Why isit such an indelible memory for me whenso little else from that trip down theAmazon can be recalled?3 We were in Hobart, Tasmania. Wehad gathered in a motel room one night.We ate a number <strong>of</strong> mushrooms we hadfound earlier that day. We spent hourssitting around mostly responding towhat anyone else was saying. It seemedto get progressively colder. One personwrapped herself in blankets that wereon the bed. Another clutched a warmradiator, and hugged it like it was asentient being. Not much happened. Itwas very late and we realized we werevery hungry. We went out in search <strong>of</strong> anopen restaurant. Everything was closedexcept for a Chinese restaurant, whichwas practically empty. We sat arounda large table. After too long an intervalsomeone came out <strong>of</strong> the kitchen andasked us what we wanted. We ordered.The food took forever to arrive. We askedfor chopsticks. The dishes <strong>of</strong> food wereplaced on a large Lazy Susan. We had tomove it around to bring whatever dish <strong>of</strong>Chinese food we wanted to sit in front <strong>of</strong>us so we could take some for ourselves.That’s when we knew the experiencewasn’t over. The Lazy Susan startedmoving. The problem was it wouldn’tstop. Someone was always moving it. Ifyou tried to grab some food with yourchopsticks while the dish passed byyou, you would inevitably fail. The LazySusan seemed to move faster and faster.Nobody was able to take any food <strong>of</strong>f it.The few people in the restaurant noticedour dilemma and watched us. Theypulled up chairs around our table andsat there silently observing us. Peoplewalking by the restaurant saw somethinghappening inside and came in and joinedthe group watching us. Every now andthen the Lazy Susan slowed sufficientlyso that we could get something out<strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the dishes <strong>of</strong> food, even if itwasn’t something that we really wantedto eat. We were convulsed in laughterthe whole time, incapable <strong>of</strong> controllingour movements or communicatingwith one another. We were not gettingdinner, as it were, but we were having agreat time. Eventually, chairs were putup on tables, and the restaurant gaveevery sign <strong>of</strong> closing for the night. Welurched out into the street, still laughing,still hungry, still wondering whetherthis was the way things worked in thesouthern hemisphere. Across the streettwo kids were walking along as a groupapproached them. One <strong>of</strong> the kids in thegroup took <strong>of</strong>f and ran full out at thetwo kids and tackled one <strong>of</strong> them. Weassumed we were watching a mugging.But all we heard was laughter, and thekids involved got up and hugged andtalked like this was the appropriate way<strong>of</strong> greeting someone in Tasmania. Wethought they must have been high onsomething or other, or they were living intoo close proximity to a large variety <strong>of</strong>marsupials, whatever that means. Whatsense, if any, could be made out <strong>of</strong> thisgroup experience? Why, after a couple <strong>of</strong>decades, do I still feel connected to thepeople who just happened to be in thatplace at that time?4 We were in Telluride, in a condoone night, about a dozen or so <strong>of</strong> us,taking mushrooms the way some peoplemight have a drink or a smoke, a form<strong>of</strong> relaxation after a long, busy day.Someone said it was the night <strong>of</strong> thefull moon. She went outside to watchit. After some time another person saidshe wanted to see it, too. She got up andwent to the door. Unfortunately, therefrigerator was so placed that she hadto pass it on her way to the door. Shemistook the door <strong>of</strong> the refrigerator forthe condo door, opened it, noticed the20 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 FUNGI Volume 4:3 Summer 2011 21