Recipes for Survival_English_tcm46-28192

Recipes for Survival_English_tcm46-28192

Recipes for Survival_English_tcm46-28192

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Recipes</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Survival</strong>:Controlling the Bushmeat TradeReport 2006Across the globe, <strong>for</strong>ests are being treatedas convertible, rather than renewableresources. The consequences of thebushmeat trade <strong>for</strong> endangered species,biodiversity and people are no longer indoubt – unless a concerted, multifacetedef<strong>for</strong>t, equal in gravity to the severity ofthe crisis is initiated, the ‘empty <strong>for</strong>estsyndrome’ will be realised in the<strong>for</strong>eseeable future.WPSA Headquarters89 Albert EmbankmentLondon SE1 7TPTel: +44 (0) 20 7587 5000Fax: +44 (0) 20 7793 0208email: wspa@wspa.org.ukWebsite: www.wspa.org.ukApe Alliance reportfunded by WSPA

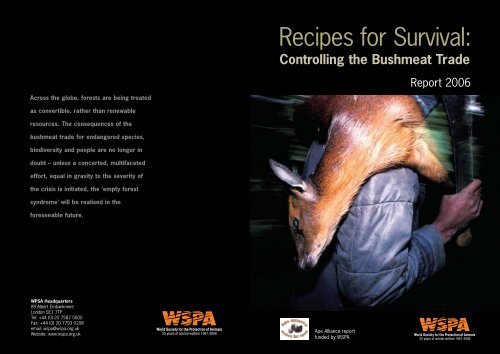

Cover:Black-frontedduiker carried bypoacher, DRC<strong>Recipes</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Survival</strong>:Controlling the Bushmeat TradeIan Redmond, Tim Aldred, Katrin Jedamzikand Madelaine Westwood2006Funded by the World Society <strong>for</strong> the Protection of Animals

3.4. The effects of bushmeat hunting onspecies and ecosystems ................................................... 323.4.1. Importance of <strong>for</strong>est wildlife ....................................... 343.4.2. Species vulnerability .................................................. 353.4.3. Geographic repercussions .......................................... 363.4.4. Species at risk .......................................................... 383.4.5. Outlook .................................................................... 403.5. Bushmeat supply, demand and price dynamics ............... 403.5.1. Supply ...................................................................... 403.5.2. Demand ................................................................... 413.5.3. Price ........................................................................ 423.6. Global health concerns linked to the bushmeat trade ..... 423.7. Outlook ................................................................................. 434. Primate bushmeat: current situation ...................................... 444.1. Introduction .......................................................................... 454.2. Scale and distribution of the problem ............................... 464.3. Exacerbating factors ........................................................... 464.3.1. Hunting techniques .................................................... 464.3.2. Armed conflict .......................................................... 464.3.3. Economic importance ............................................... 474.3.4. Persecution ............................................................... 474.3.5. The primate pet trade ............................................... 474.4. Primates at risk ................................................................... 494.5. Health implications .............................................................. 564.5.1. Simian immunodeficiency viruses and HIV .................... 574.5.2. Ebola haemorrhagic fever .......................................... 584.5.3. Simian foamy viruses ................................................. 584.5.4. Anthrax ..................................................................... 584.5.5. T-lymphotropic viruses ............................................... 584.6. Ethical Implications............................................................... 594.7. Outlook........................................................................ ..........595. Actions ongoing and their effectiveness .............................. 605.1. General actions ongoing and their effectiveness ............. 615.1.1. Government and policy ............................................... 615.1.1.1. Africa ........................................................ 615.1.1.2. USA .......................................................... 625.1.1.3. Europe ...................................................... 635.1.1.4. UK ............................................................ 635.1.1.5. International ............................................... 645.1.2. Private sector ............................................................ 655.1.3. Public awareness and education.................................. 665.1.4. Protection and management ....................................... 66CONTENTS5WSPA/APE ALLIANCE4RECIPES FOR SURVIVALContentsPageAcknowledgments .................................................................................... 7Executive Summary ................................................................................. 8Preface ..................................................................................................... 121. Introduction ...................................................................................... 142. History ............................................................................................... 183. The broader bushmeat issue: current situation ................. 203.1. Scale and distribution of the bushmeat crisis .................. 223.2. The socio-economic importance of bushmeat ................. 233.2.1. Social significance ..................................................... 233.2.2. Food security..............................................................233.2.3. Economic significance ................................................ 233.2.4. Cultural significance .................................................. 243.3. Factors contributing to commercial bushmeat hunting ... 253.3.1. Increasing human population and rising demand ........... 253.3.2. Uncontrolled access to <strong>for</strong>est wildlife facilitatedby logging, mining and hydroelectric or fossilfuel transport companies ............................................ 273.3.3. War and civil strife ..................................................... 293.3.4. Weak governance, institutional deficiencyand civil disobedience ................................................ 293.3.5. Sophistication of hunting techniques ........................... 303.3.6. Lack of capital or infrastructure <strong>for</strong> domesticmeat production ........................................................ 313.3.7. Changes in the cultural environment and discardingof social taboos and traditional hunting embargoes ...... 323.3.8. Structural adjustment plans imposed by internationalfinancial institutions resulting in civil service job losses.. 323.3.9. Unemployment, poverty and dysfunctional economies,with lack of alternative monetary opportunities ............. 32

RECIPES FOR SURVIVAL5.1.5. Capacity building ....................................................... 675.1.6. Symposia and conferences ........................................ 675.1.7. Research and monitoring ............................................ 685.1.8. Community support ................................................... 685.2. Primate-specific actions ongoing and their effectiveness 685.2.1. Policy ....................................................................... 685.2.2. Protection ................................................................. 696. Organisations involved in projects and campaigns ........... 707. Obstacles to change .................................................................... 768. Potential solutions ......................................................................... 808.1. General solutions ................................................................ 818.1.1. Protein alternatives ................................................... 818.1.2. Improving agricultural infrastructure ............................ 838.1.3. Economic opportunities and employment .................... 848.1.4. Strengthening governance and political capacityto address the bushmeat crisis ................................... 858.1.5. Community ............................................................... 868.1.6. Private sector ........................................................... 878.1.7. Protection ................................................................ 888.1.8. Education ................................................................. 898.1.9. Integration of conservation and development .............. 908.1.10. Research ................................................................ 908.1.11. Improving hunting efficiency ..................................... 918.1.12. Market dynamics ..................................................... 928.1.13. Resolving institutional deficiencies ............................. 928.2. Primate-specific solutions .................................................. 949. Conclusions...................................................................................... 989.1. General conclusions ........................................................... 999.2. Primate-specific conclusions ..............................................101Appendices ..............................................................................................102Appendix 1 Species worldwide recorded as being hunted<strong>for</strong> bushmeat ...............................................................102Appendix 2 Primate species worldwide recorded as being hunted<strong>for</strong> bushmeat ...............................................................104Appendix 3 Organisations involved in bushmeat projectsand campaigns ............................................................108Appendix 4 Index of organisations involved in bushmeat projectsand campaigns ............................................................108References ...............................................................................................109ACKNOWLEDGMENTS7WSPA/APE ALLIANCE6AcknowledgmentsThe authors are grateful to WSPA <strong>for</strong> funding this research, and to all the organisationsand individuals who contributed in<strong>for</strong>mation and their thoughts and opinions. The listof organisations is appended in Appendix 3, but in particular we would like to thank theBushmeat Crisis Task Force and the members of the Ape Alliance <strong>for</strong> responding toour questionnaire and subsequent emails. Any mistakes or omissions are solely ourresponsibility, and we encourage readers to send us corrections and updates.We also thank BCTF and IUCN <strong>for</strong> the use of their online resources when producingour databases.Special thanks go to Jane Wisbey <strong>for</strong> her skilful editing in the final stages, and to WSPAand especially Jo Hastie and Garry Richardson <strong>for</strong> their help.Participants in the Ape Alliance/WSPA Bushmeat Side-event at the GRASP Inter-Governmental Meeting in Kinshasa, DRC (5th – 9th September 2005), made manyuseful comments which we incorporated as appropriate.We would also like to recognise the role of our families and friends <strong>for</strong> their supportand tolerance during many late nights and working weekends.

8RECIPES FOR SURVIVALExecutive SummaryThe bushmeat trade provides a staple in the diet of the people of West and Central Africa,as well as in many other parts of the world under different names (wild-meat, game, bushtucker,chop, etc.). Over a thousand species are hunted / traded, from caterpillars toelephants, but many of these species are facing population crashes through overexploitation<strong>for</strong> commercial purposes. This ‘bushmeat crisis’ will inevitably lead to speciesextinction and consequent protein shortages unless it can be brought under control. Thereare also serious public health concerns regarding potential zoonoses on poorly preservedbushmeat. Thus, <strong>for</strong> bushmeat to be acceptable, it must be legal, sustainable and diseasefree(or ‘LSD’, Redmond, In press). In other words, Legal – no hunting or trading ofprotected species or hunting in protected areas; Sustainable – numbers hunted must beless than or equal to reproductive capacity, and Disease-free – markets should be subjectto meat inspections and other public health regulations the same as domestic meat.These are the standards that, if en<strong>for</strong>ced, would protect endangered species, publichealth, food security and sustainable livelihoods. In an ideal world, the animals wouldalso be killed using humane methods, thereby reducing animal suffering too.Bushmeat and apesDespite the wide range of taxa and the complex issues involved, media coverage of the‘bushmeat crisis’ has focused largely on the great apes. Bushmeat, however, is seldomape-meat. Surveys of African markets have shown that ape-meat, if present, comprisesonly one or two per cent of the trade (Stein, 2002b); the rest is mostly meat of <strong>for</strong>estungulates, large-bodied rodents and monkeys. Even so, ape populations decline underalmost any level of hunting, because they reproduce so slowly and the sudden deathof key individuals disrupts their complex societies.What of the few cultures <strong>for</strong> whom eating apes is a tradition? It is important that peoplewho grew up thinking it normal to eat gorilla, chimpanzee or bonobo body-parts, arenot demonised by those who baulk at the thought. But equally, people who do eatapes must realise that they will stop doing so soon. At current inferred rates of decline– there will simply be none left within our lifetime. Surely it is better to stop now,by choice, than later by extinction?EXECUTIVE SUMMARYConclusionsThis review set out to examine the current state of knowledge of the bushmeat trade,and how the conservation community has reacted to the bushmeat crisis. Manyorganisations have raised money to respond to the threats posed to charismaticendangered species; it is interesting to note how this money has been applied. Insummary, the results show:• Hundreds of species are being hunted <strong>for</strong> food but surprisingly, preliminary resultsshow that 45 per cent of them are insects, and only 23 per cent mammals and 20per cent bird species.• 27% of recorded mammals, 63% of birds, 61% of reptiles and 35% of amphibianshunted are listed by IUCN as endangered or vulnerable to extinction.• The greatest number of recorded bushmeat projects concern research at 24%, theneducation at 11% and protection 9%. Very few projects address the issue of providingalternative protein sources, better management of wildlife or alternative livelihoods.• The number of projects commencing per year increased dramatically in 1999 and2000; the first Ape Alliance bushmeat review was published in 1998.• The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has the most projects (58), followed byCameroon (53), Gabon (35) and Congo (23), but most countries have only one or ahandful. The USA ranks third with 47 projects, but these are mainly awareness raisingand education.How can the bushmeat trade be controlled?Whilst it is clearly necessary to understand a problem be<strong>for</strong>e designing a solution,there is a growing feeling that more research is not the top priority at this stage. Otheractivities urgently need funding if the bushmeat trade is to be reduced to sustainableoff-take levels of legally hunted species. These activities include (in no particular order):Education – is needed at every level of society, and materials / activities must be tailoredto the target audience: in villages with hunters and traders, in urban markets / restaurantswith traders and consumers; law-en<strong>for</strong>cement agents, judiciary and decision-makers.Further funding is also needed <strong>for</strong> NGOs and Education Ministries to reproduceeducational materials <strong>for</strong> schools and wildlife centres. Training should be provided <strong>for</strong>environmental journalists to increase the number and quality of articles in local pressand stories on local radio / television news channels. The Great Ape Film Initiative hasestablished a system of increasing the number of ape documentaries shown in rangestates, but it limited by lack of funds.Wildlife law en<strong>for</strong>cement and prosecution – is weak throughout the regions wherebushmeat is traded. There is an urgent need to:• build the capacity of law en<strong>for</strong>cement agencies,9

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVAL• provide incentives <strong>for</strong> wildlife law en<strong>for</strong>cement officers, e.g. set up open andtransparent bonus and award schemes <strong>for</strong> good work• train officers in evidence gathering and preparing cases <strong>for</strong> prosecution• give training in wildlife law to members of the judicial system, and• publicise fines and prison sentences to deter others.These are the approaches practiced by the Last Great Ape Organisation (LAGA) inCameroon. Following reports of initial successes using this approach in Cameroon, LAGAhas been requested by DRC authorities to advise on setting up a similar project there, andother African countries are showing interest. This suggests a need to run training coursesand possibly explore secondments in Cameroon <strong>for</strong> officials from surrounding countries.One might also investigate the secondment to the region of en<strong>for</strong>cement officers ormembers of the judiciary from UK / Europe to work with counterparts in building capacity.Sanctuaries and Wildlife Centres – play an important role in housing confiscatedlive animals and serve as centres <strong>for</strong> education and awareness-raising of the bushmeatcrisis. Some countries which have a significant problem with live animal trade andillegally held pets, still have nowhere to house confiscated animals, and so confiscationsare rare and require special arrangements each time.The country from which many of the confiscated African <strong>for</strong>est primates originatesis the DRC. Sanctuaries in Kenya, Zambia, South Africa (via Angola), etc are full ofsmuggled primates – especially chimpanzees – from DRC. But apartfrom Lola ya Bonobo, there are no adequate facilities in DRC, and sofew confiscations. As part of the DRC National Great Ape <strong>Survival</strong> Plan(NGASP), there is a move to convert DRC’s three zoos (Kinshasa,Kisangani and Lubumbashi) into sanctuaries / wildlife education centres.If a firm commitment that meets the concerns of NGO partners can bereached, we will have the opportunity to do <strong>for</strong> chimpanzees and otherillegally traded wildlife, what Lola ya Bonobo has done <strong>for</strong> bonobos.Gabon also has an illegal wild animal trade and no facility to houseconfiscated animals – hence, no confiscations, and no law en<strong>for</strong>cementor prosecutions. The draft Gabon NGASP highlights this need, andseeks support <strong>for</strong> a sanctuary to be established <strong>for</strong> this purpose.Alternative protein – is the corollary of improved law en<strong>for</strong>cement. If the bushmeat tradein legal species is to be reduced to sustainable levels, and the illegal trade stopped,alternative sources of protein must be introduced to the system. These might include:• vegetable protein sources (nuts, mango-kernels, soy beans, smoked texturedvegetable protein (TVP))• domestic animals: improved husbandry of traditional domestic stock;• developing methods of humane farming of wild species, such as grass-cutters, landsnails;farming edible insects – an as yet untried option with many advantages –EXECUTIVE SUMMARYperhaps adapting the methods used <strong>for</strong> silkworms to suitable African species (thishas been done <strong>for</strong> silk rearing in Uganda, but not yet as a food source).• managing sustainable hunting of legal species in <strong>for</strong>ests (where hunting is allowed).These are effectively business opportunities <strong>for</strong> enterprising entrepreneurs, andthere<strong>for</strong>e more likely to appeal to development organisations. It is, however, animportant measure to support, so interested donors could, <strong>for</strong> example, hold seminarsadvising bushmeat dealers of how to source alternatives, perhaps making small loansto set them up in business importing or manufacturing smoked vegetable proteinproducts designed <strong>for</strong> bushmeat consumers.Alternative livelihoods – are one way of removing poachers from the bushmeat trade.Jobs in conservation, research, tourism, cultural crafts and displays, improved farmingtechniques, sustainable harvest of Non-Timber Forest Products all present possibilities.Bio-monitoring – is essential <strong>for</strong> good wildlife management; the training ofcommunities and/or rangers to gather data on the health of the <strong>for</strong>est, speciesnumbers, and also the health of human population in and around hunting zones, areimportant measures in establishing a system to control the bushmeat trade. Whereexisting projects have established a <strong>for</strong>mula that works, these should be expandedor replicated (with necessary adaptations <strong>for</strong> local differences) in another area ofhigh-biodiversity value habitat under threat from commercial bushmeat hunters.Protection of species function,not just survival of speciesFor more than a century, protected areas have been at the centre of conservationthinking, and ef<strong>for</strong>ts have concentrated on ensuring that protected areas includerepresentative populations of important species. This gives the impression that aslong as a population of a species survives somewhere, then we have achieved ourconservation goal. But preventing total extinction is surely a last resort goal, andwe should not be setting this last resort as our target. Such a goal (and much ofthe popular conservation literature) carries with it the idea that species are like livingornaments that it would be a shame to lose, and ignores the important role eachspecies plays in the ecology of the habitat that evolved with it. Large mammalsin particular, such as apes and elephants, play such an important ecological role –dispersing seeds in their dung, pruning trees as they pluck leaves and creating lightgaps in the canopy as they break branches – that they are sometimes referred to asthe gardeners of the <strong>for</strong>est. As such, they are needed in habitats which have evolvedto depend on them across the whole of their historical range, and in densitiesappropriate to their function. If we value <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>for</strong> the products and services theyprovide, and want healthy <strong>for</strong>est ecosystems, is it not foolish to shoot the gardeners?11WSPA/APE ALLIANCE10Above:Chimpanzeeorphans atthe TacugamaChimp Sanctuary,Sierra Leone© WSPA

WSPA/APE ALLIANCE12RECIPES FOR SURVIVALPrefaceIt is a decade since WSPA drew the world’s attention to the Slaughter of the Apes.The report was influential in triggering the launch of the Ape Alliance in 1996 andthe commissioning of The African Bushmeat Trade – <strong>Recipes</strong> <strong>for</strong> Extinction, a detailedreview of what was then known about bushmeat trade (Ape Alliance, 1998). There hassince been a flurry of academic and NGO activity, and a widespread recognition of the‘bushmeat crisis’ by governments and inter-governmental agencies. This new reviewwas commissioned in late 2004 by WSPA to summarise the current state of knowledgeof the bushmeat trade, and assess what is being done to solve the problems that thislargely unregulated trade causes. It is hoped that the database of projects andreferences compiled will be of use to all those interested in this issue, and that theconclusions drawn will help to guide the application of funds in the future. For furtherdetails on the database, see Section 6As well as the Ape Alliance network, resources used in researching and compiling thisreport include the scientific literature, reports from organizations involved in thebushmeat issue, media and news reportage, documentaries, personal contacts and theWorld Wide Web.Species analysis:The IUCN Red List website (www.redlist.org) was the principal resource <strong>for</strong> compilingthe species database, which was developed with in<strong>for</strong>mation from the scientificliterature, reports and research data from concerned organisations.The databases presented in this report are by no means exhaustive, but represent adetailed overview and are designed to be used and expanded upon. Likewise, thegraphs and figures generated from our data are thorough but not fully comprehensiveand should be used as an interpretative tool.The data and research presented here should be treated as an active, ongoingresource and as such, comments, corrections and further contributions are welcome.With effective communication, the ever-changing international bushmeat crisis can betackled with appropriate and novel solutions.Comments and corrections should be sent to: BushmeatWG@4apes.comTaxonomic note:Except where indicated otherwise, this work follows Groves (2001), which recognisestwo species in each of the three great ape genera, Gorilla, Pan and Pongo. We note thenewly described sub-species of Eastern Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes marungensisdescribed in Groves (2005).The authors are grateful to WSPA <strong>for</strong> funding this research, and to all the organisationsand individuals who contributed in<strong>for</strong>mation and their thoughts and opinions. The listof organisations is appended in Appendix 3, but in particular we would like to thank theBushmeat Crisis Task Force and the members of the Ape Alliance <strong>for</strong> responding toour questionnaire and subsequent emails. Any mistakes or omissions are solely ourresponsibility, and we encourage readers to send us corrections and updates.We also thank BCTF and IUCN <strong>for</strong> the use of their online resources when producingour databases.Special thanks go to Jane Wisbey <strong>for</strong> her skilful editing in the final stages, and to WSPAand especially Jo Hastie and Garry Richardson <strong>for</strong> their help.Participants in the Ape Alliance/WSPA Bushmeat Side-event at the GRASP Inter-Governmental Meeting in Kinshasa, DRC (5th – 9th September 2005), made manyuseful comments which we incorporated as appropriate.We would also like to recognise the role of our families and friends <strong>for</strong> their supportand tolerance during many late nights and working weekends.PREFACE13

IntroductionIt is ten years since the alarm bells first began to ring about ‘the bushmeat crisis’, asthe booming trade in the meat of wild animals quickly became known. In this decade,we have seen bushmeat rise from a fringe concern of a few NGOs to being firmly on theinternational agenda, of equal concern to both conservation and development agencies.The problems raised by the commercial bushmeat trade – whether its activities arelegal or illegal – are complex, and any solutions proffered must reflect this. Bushmeatcuts across concerns about endangered species and biodiversity loss, povertyalleviation, food security, livelihoods and the sustainable utilisation of natural resources.The problems it raises are widespread and cannot be approached in isolation fromother global environmental challenges, such as climate change, desertification,declining marine fish stocks and emerging diseases in an increasingly crowded world.Prevailing scientific opinion is that we are entering a period of mass extinction, <strong>for</strong>which the human species is almost entirely accountable. The geographic nuclei ofthese extinctions are areas where human populations and pressure from hunting andagriculture are most intense (Ceballos & Ehrlich, 2002). Human use of biodiversity isnatural, but the scale of that use has risen exponentially in the past century.INTRODUCTIONAbove: Legaltraditional huntersbutcher a duiker,Central AfricanRepublic15© Ian Redmond© Ian Redmond1Opposite:Bushmeat vendor,DRC, with monkeycarcass, smoked topreserve meat.

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALreaches international markets as part of the US$159 billion annual global wildlife trade(Wasser et al, 2004).Even in the world’s most productive ecosystems, modern hunting has proved to beunsustainable, and in tropical <strong>for</strong>ests, where the meat productivity is too low to supporteven subsistence hunting if the human density is more than about one person per squarekilometre, the threat posed by commercial trade is acute (Bennett et al, 2002).Moreover, in <strong>for</strong>ested habitats, where wildlife is difficult to observe, the impact of huntingmay go undetected until after the damage is too severe to rectify (Wasser et al, 2004).The bushmeat crisis is a complex, multifaceted issue that poses one of the mostchallenging problems in contemporary conservation. An all encompassing descriptionwas devised by Mainka and Trivedi in 2002:“Wildlife populations and the livelihoods of people in many countries are threatened byescalating unsustainable use of wild meat, driven by increasing demand due to humanpopulation growth, poverty and consumer preferences and aggravated by problems ofgovernance, use of increasingly efficient technology and provision of hunting access inremote areas by logging roads.”Awareness of and support <strong>for</strong> addressing the crisis was instituted during the mid-1990s and has since been mainstreamed by wildlife and humanitarian concerns, alongwith the global health implications of hunting and eating bushmeat. Much work hasalready been carried out to combat the bushmeat trade, yet despite progress, huntingstill continues unabated.In this report, we will explore the current status of the bushmeat trade, both in broadterms and <strong>for</strong> primates in particular. We will outline the scale and consequences ofhunting and the factors and stakeholders driving it. We will assess what has alreadybeen achieved and what successes need to be built upon to bring about further change.INTRODUCTION17WSPA/APE ALLIANCE16Despite progress in agricultural productivity and plantation <strong>for</strong>estry, natural biodiversityis still important to humans in providing food security, micronutrients, medicines, fuel,construction materials, raw materials, farming inputs (such as fodder, compost, fencingand stakes), ecosystem services (such as soil, watershed, pollinator and wildlifehabitat) and as an asset convertible into other assets, such as savings, investments,barter or trade (ABCG, 2004).Though <strong>for</strong> decades de<strong>for</strong>estation has been cited as the most immediate threat totropical wildlife in <strong>for</strong>est habitats, popular contemporary belief is that hunting is cause<strong>for</strong> greater concern. The term ‘empty <strong>for</strong>est syndrome’ (Red<strong>for</strong>d, 1992) has now beenintroduced in recognition of major global anxiety over commercialised hunting and thewidespread prediction that large species will disappear long be<strong>for</strong>e the <strong>for</strong>ests do.‘Empty savannah syndrome’ is also becoming a reality, with the rise of commercialbushmeat trade from savannah habitats in Africa and elsewhere.Below:The Goldencrowned sifakais threatened bybushmeat huntingand de<strong>for</strong>estation.Traditionally, decision-makers and <strong>for</strong>est managers in the developed world havedisregarded the value of non-timber <strong>for</strong>est products to people, ranking them belowthe more productive timber industry (Nasi, 2001). The subsistence of traditional <strong>for</strong>estpeople on wildlife has occurred since humans first evolved, but the past decade hasseen a drastic increase in the amount of wild meat being removed from <strong>for</strong>ests (Wilkie& Carpenter, 1999). People eat bushmeat because it is af<strong>for</strong>dable, familiar, culturallytraditional or prestigious, and because it tastes good and adds variety to domesticallycultivatedprotein (Wilkie et al., 2005). Economic recession over the past 20 years hasdriven the commercialisation of bushmeat as a trade item, and today, bushmeat© Pete Ox<strong>for</strong>d/naturepl.com

HistoryWildlife has been hunted <strong>for</strong> food since humans first evolved, but this has onlyrecently become a problem of crisis proportions. In rural Africa, people havetraditionally generated income by growing and selling rice, coffee, cacao, cottonand peanuts; hunting wildlife <strong>for</strong> meat was mostly subsistence-motivated or <strong>for</strong> barter.Historically, in Congo and Cameroon, bartering existed between Baka pygmies andBantu farmers, who exchanged wild meat and agricultural produce respectively(Pearce & Ammann, 1995). Subsistence hunting is still important today in thesecommunities (Matsura, 2004).The past 20 years has seen a degradation of roads and trading routes in the war-tornregions of the Congo Basin, making it difficult to transport bulky agricultural goods tomarkets (Wilkie & Eves, 2001). The commercial bushmeat trade emerged here due tothe imperative of rural people to replace their incomes with relatively high value, easilytransportable goods such as bushmeat and/or ivory. Hunting camps were soonestablished by migrants suffering economic hardships in outlying cities; they provedeven less inclined to practice restraint than rural hunters nutritionally dependent onwildlife. It has now become difficult to differentiate subsistence and commercial hunting(Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999).The sudden boom in the bushmeat trade was facilitated in no small way by the loggingindustry. Traditionally, hunters would have to trek <strong>for</strong> days to reach new hunting areas,carrying snares, spears, bows and arrows and bringing back only what bushmeat theycould physically carry. Logging provided road access to remote areas, as well ascheap transport <strong>for</strong> importing large numbers of carcasses to urban markets, therebyincreasing capacity to hunt and inflating profitability of the trade. Furthermore, shotgunsbecame more readily available after the colonial period (Barnes, 2002) and werevirtually universally adopted by anyone who could af<strong>for</strong>d to buy one (or hire one from anentrepreneur) to increase hunting success. Thus, <strong>for</strong> a small investment, the economicpay-off was substantial, and uncontrolled hunting became widespread.Today, bushmeat continues to be an economically important food and trade item.Much evidence exists to show that, <strong>for</strong> most species, the current level of huntingis unsustainable.HISTORY2Opposite: Lorrytransportingtimber fromprimary rain<strong>for</strong>est,Sabah, Borneo.19© Neil Lucas/naturepl.com

THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEThe broader bushmeatissue: current situation3There are two broadly opposing academic views of the bushmeat ‘crisis’, which can becharacterised as:(i) Anthropocentric – in which declining stocks of prey species are seen as loss of ahuman resource, leading to:• threat to livelihoods• threat to food security• threat to cultural values• loss of other potential human uses of ecosystem, e.g. ecotourism, NTFPs (non timber<strong>for</strong>est products), bio-prospecting.(ii) Biocentric, in which the same situation is seen in terms of a loss of biodiversity:• common species become rare, endangered species become extinct• breakdown in ecological processes• local loss of ecological services leads to negative impact on biosphere, ultimatelyaffecting all life-<strong>for</strong>ms.These views are sometimes characterised as ‘pro-people versus pro-wildlife’, but thereality is much more complex than that; ef<strong>for</strong>ts to aid sustainable development arehampered by political and economic factors far removed from the biological systemson which they depend, and yet the destruction of those systems due to overexploitationwill negatively impact on the very people the aid is designed to help(<strong>for</strong> a discussion of these issues, see Robinson, 2006, versus Brown 2006 anda response by Redmond 2006).Bushmeat harvesting has strong parallels with fisheries. Both:• are open access resources, where it is difficult to control off-take• have hidden assets, and so difficult to assess stocks• show improved yield with modern technology, and better access leads toover-exploitation• show boom and bust pattern of exploitation as population crashes lead to localextinction.Opposite:Wild animals <strong>for</strong>sale on marketstall, Lagos,West Africa.21© Fabio Liverani/naturepl.com

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALAnd in both cases, restraining measures in response to declining stocks face:• resistance to change by those whose livelihood depends on harvesting or trade• cultural conservatism in consumption patterns despite evidence of declining stocks• difficulty in imposing top-down restraint (law en<strong>for</strong>cement)• lack of self-restraint because open access resource – the ‘tragedy of the commons’.3.1 Scale and distribution of the bushmeat crisisThere is evidence to show that the multi-million dollar bushmeat trade has nowsurpassed habitat loss as the greatest threat to tropical wildlife (Brashares et al, 2004;Bennett et al, 2002). In the Congo Basin, researchers estimate that up to five millionmetric tons of bushmeat is traded annually (Wilkie & Carpenter, 1999; Fa et al, 2002),representing the most immediate threat to the region’s wildlife over the next 5 – 25years (Wilkie & Carpenter, 1999; Robinson et al, 1999; BCTF, 2004b). By comparison,up to 0.15 million tons is traded in the Amazon Basin (Fa et al, 2002; Robinson &Red<strong>for</strong>d, 1991), with an estimated market value of $190.7 million. (Peres, 2000).Annual harvest rates in Sarawak reach 23,500 tons (Bennett, 2000); elsewhere in Asia,the scale of the problem is largelyunquantified, though local extinctionshave occurred (Kümpel, 2005).The commercial trade in bushmeatoccurs across almost all of tropicalAfrica, Asia and the Neotropics(Robinson & Bennett, 2000), but it ismost critical in the densely <strong>for</strong>estedregions of Central and West Africa.Here, the magnitude of hunting is sixtimes the sustainable rate (Bennett,2002). The Congo Basin is the world’ssecond largest rain<strong>for</strong>est, stretchingacross 10 countries and housingmore than half of Africa’s animalspecies. Uncontrolled bushmeathunting in this region there<strong>for</strong>ethreatens the health of a <strong>for</strong>estecosystem of planetary importance,both in terms of biodiversity and ofglobal climate stability.Until recently, bushmeat hunting in East and Southern Africa was thought of as asubsistence-motivated activity, carried out exclusively by rural families with a history oftraditional use, but commercial trade across the region is now of serious conservationTHE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEconcern (Barnett, 2000; Born Free, 2004). At least 25% of meat in Nairobi butcheriesis bushmeat, sold under the auspices of domestic meat, and a further 19% is adomestic-bushmeat mix, suggesting mixing and cross-contamination during storageor transit (Born Free, 2004).Bushmeat is also a problem on a global scale, since a proportion of it (albeit low)enters international markets. It is not difficult to find bushmeat in Paris, Brussels,London and New York (Agnagna, 2002). Between 4,000 and 29,000 tons of illegalmeat enters the UK annually from non-EU countries, with more entering undetected(Kümpel, 2005). Much of this is meat of domestic animals; the proportion ofbushmeat is not known.Evidence shows that illegal wildlife trade in the UK operates through existing organisedcrimesmuggling routes. 50% of people prosecuted <strong>for</strong> wildlife trade have had previousconvictions <strong>for</strong> drugs and firearms (Cook et al, 2002). The UK has some of thestrongest CITES legislation in the EU, <strong>for</strong>tified by COTES (Control of Trade inEndangered Species) regulations. But offenders are rarely prosecuted, because HerMajesty’s Customs and Excise (HMCE) destroy all confiscated meat on the groundsof health risks, without first identifying the species (Kümpel, 2005). The proportionof meat from endangered species in UK imports has not, there<strong>for</strong>e, been quantified.Bushmeat imported into Europe is on the increase, indicating a need <strong>for</strong> strongercontrols at airports (CITES, 2004).3.2 The socio-economic importance of bushmeat3.2.1 Social significanceThe network of people involved in the bushmeat industry includes (locally) the ruralpoor, commercial poachers, traders, vendors (including restaurateurs), loggingcompanies, vehicle drivers (who ferry meat to urban centres) and local administrations,as well as (internationally) <strong>for</strong>eign businesses that consume tropical timber, governmentand non-governmental organisations.3.2.2 Food securityThe loss of wildlife threatens the livelihoods and food security of those who mostdepend on it as a staple or supplement to their diet (ABCG, 2004). Wildlife providesprotein <strong>for</strong> many poor rural families without land or access to agricultural markets.In several tropical countries, there is no replacement <strong>for</strong> bushmeat (Kaul et al, 2004).Surveys reveal that bushmeat represents 80% of all animal-based household proteinconsumed in Central Africa, and more in some regions (Draulans & Van Krunkelsven,2002; Pfeffer, 1996). Where crop-based agriculture is practiced, bushmeat hunting ofcrop-raiding species occurs in tandem to fulfil the twin imperatives of meeting proteinneeds and defending crops to maximise agricultural output <strong>for</strong> further economic gain.23WSPA/APE ALLIANCE22Below: WestAfrican monkey,smoked, on sale inLondon. The vendorwas successfullyprosecuted.© Ian Redmond

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALThe Food and Agriculture Organization recommends an annual intake of 22kg of meatprotein per capita. In many areas, bushmeat consumption exceeds this (Barnett, 2000).With average Central Africans eating as much meat per capita as Americans but lackingthe abundant agricultural protein sources found in the US and Europe, a reduction inbushmeat hunting and consumption could <strong>for</strong>ce already malnourished people to furtherreduce their meat consumption (Barnett, 2000).Of 800 million people in developing countries, 200 million in Sub-Saharan Africa areundernourished (ABCG, 2004). In many African regions, agricultural productivity isdiminished by poor soils giving disappointing yields, land tenure security, high seasonalvariability and by prevalence of tsetse fly and trypanosomiasis, which kills livestock(Barnett, 2000, Stein & BCTF, 2001). Even in areas where livestock can be raisedsuccessfully, they are largely regarded as insurance commodities, relied on as a bufferduring periods of severe hardship. Domestic meat tends to be available only in rural orurban markets that are situated close to savannahs and ethnic groups with a traditionof pastoralism (Barnett, 2000). In Gabon, 38% of people are dependent on agriculturecompared with 60 – 70% in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Democratic Republicof Congo (DRC) (Fa et al, 2003).The current non-bushmeat protein sources are mainly starchy root vegetables such asmanioc or agricultural meat, seafood and fish. Some of this is available domesticallyand some imported (6% imported in DRC and 55% in Congo-Brazzaville (Congo-B)). Ingeneral, the food production in this region has not increased significantly in the past40 years; in Congo-B, it has decreased by 10% annually (Fa et al, 2003).3.2.3 Economic significanceThe annual contribution of the bushmeat trade to national economies is difficult toestimate, because it is largely unregulated and un-taxed. Nevertheless, it has beenestimated to equal US$24 million in Gabon, US$42 million in Liberia, US$117 million inCôte d’Ivoire and up to US$150 million in Ivory Coast (Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999;Kümpel, 2005). The estimated overall annual value of the trade could exceed US$1 billion,with commercial hunters in Central Africa making up to US$1,000 per year – more thanthe average household income (BCTF, 2000c; Wilkie & Eves, 2001). Many rural familiesliving in extreme poverty are making less than US$1 per day (Merode et al, 2004).In Central and West Africa, the trade in bushmeat can supply 90% to 100% of allhousehold income <strong>for</strong> rural families (Matsura, 2004; Williamson, 2001). In Eastern andSouthern Africa, 39% of household income is supplied by the bushmeat trade; in theKitui District of Kenya, even part-time trading provides an income competitive with more<strong>for</strong>mal professions (Barnett, 2000). A study found that 74.5% of people arrested <strong>for</strong>illegal hunting in Serengeti National Park said that they hunted to generate cash incomeand only 24.7% claimed they hunted to obtain food (Loibooki et al, 2002). The samestudy reported that those who owned livestock were significantly less likely to hunt wildanimals but that those who did hunt relied on hunting to supply 51.4% of their protein.THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEAn estimated 5,226 young adult men from the subsistence farming communities on theboundary of the National Park obtained their primary income from illegal hunting. Foodexpenditure <strong>for</strong> both poor and wealthy families in Kenya represents more than 70%of monthly income, and so savings made from eating no-cost bushmeat significantlycontribute to living standards (Barnett, 2000).In 1996, it was estimated that wild meat represented 1.4% (about US$150 million) ofCôte d’Ivoire’s gross national product (Williamson, 2001); 120,000 tons of wild meatwas harvested – more than double the annual production from domestic livestock(Caspary, 1999, cited by Williamson, 2001).Bushmeat allows people to purchase materials and items that a subsistence life cannotprovide, as well as generating income <strong>for</strong> shelter, clothing, taxes and schooling (Ziegleret al, 2002; Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999). At a time when per capita spending on socialservices is decreasing, and incomes have plummeted due to falling agricultural prices andcurrency devaluation, the monetary incentive <strong>for</strong> hunting bushmeat is highly attractive.The likelihood of detection or punishment is minimal and the cost/benefit ratio is veryfavourable, further enhancing the appeal and justification <strong>for</strong> hunting wildlife. Indeed, theimportance of bushmeat in the Gross Domestic Product and national economy is nowbeing recognised in Central and West Africa (Barnett, 2000; Kümpel, 2005).3.2.4 Cultural significanceCultural and religious importance is also attributed to bushmeat (Apaza et al, 2002).Hunters in Kenya, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe have esteemed status, becausethey provide food <strong>for</strong> the less capable elderly and female-led households (Barnett,2000). Hunting is, in many cases, a revered activity and/or a social pastime.Furthermore, bushmeat is often sought after by urban elites seeking to retain links toa traditional village lifestyle (BCTF, 2004). In Sarawak, <strong>for</strong> example, city-dwelling menhunt recreationally, just as do many of their North American and European equivalents.3.3 Factors contributing to commercialbushmeat huntingThe most important driving factors in commercial bushmeat hunting are:1. Increasing human population and rising demand2. Uncontrolled access to <strong>for</strong>est wildlife facilitated by logging, mining and hydroelectricor fossil fuel transport companies3. War and civil strife4. Weak governance, institutional deficiency and civil disobedience5. Sophistication of hunting techniques6. Lack of capital or infrastructure <strong>for</strong> meat production7. Changes in the cultural environment and discarding of social taboos and traditional25WSPA/APE ALLIANCE24

WSPA/APE ALLIANCE26RECIPES FOR SURVIVALhunting embargoes8. Structural adjustment plans imposed by international financial institutions resulting incivil service job losses9. Unemployment, poverty and dysfunctional economies, with lack of alternativemonetary opportunitiesLocal factors, including topography, available infrastructures, market access, taboos,religions, weapon availability and hunting seasons, are also important in affecting trade(Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999).3.3.1 Increasing human population and rising demandWhere people live at low densities, wildlife populations are given the chance to recoverfrom gradual harvesting. But as human populations increase, so, inevitably, does therate of <strong>for</strong>est loss and demand <strong>for</strong> bushmeat.There are 522 people per km 2 in Asia, 99 per km 2 in West and Central Africa and 46per km 2 in Latin America (Milner-Gulland et al, 2003). Between 1950 and 1992, thepopulation of Sub-Saharan Africa increased by 387% (ABCG, 2004).Thirty-four million people living in the <strong>for</strong>ests of Central Africa are consuming approximately1.1 metric tonnes of bushmeat annually – the domestic equivalent of 4 million cattle –matching consumption rates of meat in Europe and North America (BCTF, 2000c).In West Africa, human population densities are even higher, and hunting here has beenso extensive that dietary dependence on rodents, the only group remaining inabundance, has emerged (BCTF, 2004). The current rate of population growth in WestAfrica is 2.6% per annum, but as the number of people grows and the area of <strong>for</strong>estshrinks, pressure and demand will exceed this rate (Barnes, 2002).Across Africa, the number of consumers has increased from 100 million in 1900 tomore than 800 million in 2000. A projected increase to 1.6 billion is expected in lessthan 25 years (Apaza et al, 2002). National statistics obscure exponential pressures(Barnes, 2002), and across Africa, it is likely that bushmeat demand will increase by2 – 4% annually (Eves et al, 2002). Wildlife populations are incapable of replenishingrapidly enough to supply current demand, let alone future projections (Wilkie &Carpenter, 1999).If the main protein source in a tropical moist <strong>for</strong>est is wild meat, then the sustainablecarrying capacity should be no more than one person per km 2 (Robinson & Bennett,2000, Ling et al, 2002). Even then, trade routes would need to be poorly establishedand population growth rates low (BCTF, 2004b).The demand <strong>for</strong> bushmeat around the world is increasing as expatriate Africanpopulations expand. Up to 427kg of animal products (including bushmeat) areTHE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEconfiscated at Heathrow each week. A suitcase of bushmeat can have a street valueof £1000. The preparation of bushmeat <strong>for</strong> transport makes it very hard to identifyspecies confiscated; DNA (mitochondrial) analysis is becoming an important tool inidentification and law en<strong>for</strong>cement (Kelly et al, 2003).Sustainable subsistence hunting may still be possible in the few areas where humanpopulation densities do not exceed two people per km 2 , growth rates are low and tradingroutes to bushmeat markets have yet to be established (BCTF, 2004). But <strong>for</strong> great apesand other species with slow reproduction rates and slow maturation, a hunting pressureof even a few percent per annum can result in a decline leading to extinction.3.3.2 Uncontrolled access to <strong>for</strong>est wildlife facilitated by logging,mining and hydroelectric or fossil fuel transport companiesPrivate logging companies have timber exploitation rights to major tracts of tropical<strong>for</strong>est (Elkan, 2002). In Central Africa, annual <strong>for</strong>est loss ranges from 0.2% in Congo-Brazaville to 0.7% in DRC (Fa et al, 2003). An estimated 80,000ha of <strong>for</strong>est isdestroyed in the Congo Basin each year <strong>for</strong> a total of 80 commercially logged species(Gouala, 2005; BCTF, 2004).Africa’s annual production of about 11 million cubic metres of wood make it the thirdmost important timber producer worldwide (Pearce & Ammann, 1995). In 1996, 81%of exploited Cameroonian <strong>for</strong>ests were under the control of EU-based companies(WSPA, 1996). In Gabon, logging is particularly prevalent, with the area of harvestable<strong>for</strong>est rising from 3 million hectares in 1960 to 11 million (60% of the national territory)in 2000 (WRI, 2000, cited by Medou, 2001).There are currently no FSC-accredited logging concessions in the whole of CentralAfrica (Peterson, 2003). Forest recovery periods are generally not satisfied be<strong>for</strong>e newconcessions are allocated (Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999).Though ‘defaunation’ of <strong>for</strong>ests is widely perceived as a greater threat to tropicalspecies survival than habitat loss, it is the synergy between the hunting andde<strong>for</strong>estation that is the greatest cause <strong>for</strong> concern (Milner-Gulland, 2002). The loggingindustry provides the transport infrastructure (roads, airports, ferries) and tradingroutes necessary <strong>for</strong> the bushmeat industry, and there is evidence to suggest that,where transport infrastructure is poor, hunting is less severe (Butynski & Koster, 1994).Pearce (1995) reported a significant reduction of hunting when Congolese loggingtrucks were on strike, and some hunting camps closed completely.Roads built by prospecting logging companies cause indiscriminate fragmentation of<strong>for</strong>ests and provide commercial hunters with virtually unlimited access to remote areas,<strong>for</strong>cing rural families that lack the legal or practical capacity to restrict hunting toharvest as much as possible be<strong>for</strong>e others do (BCTF, 2000a).27

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALWithin logging concessions, large numbers of workers create a massive demand <strong>for</strong>bushmeat and provide an in-situ market <strong>for</strong> hunters to sell meat. As a result, some ofthe most lucrative hunting settlements are those established within logging townships.Families living in logging communities eat two to three times more bushmeat than ruralcommunities (Wilkie & Eves, 2001). Very few logging concessions currently providefood <strong>for</strong> their work <strong>for</strong>ce.Mining <strong>for</strong> tantalum, a rare metal used in capacitors <strong>for</strong> mobile phones and portablecomputers, has created further pressure on Central African wildlife. The demand <strong>for</strong>PlayStations in 2000 led to a world shortage of tantalum and a massive increase in itsprice from $40 to $500 per pound (Hayes, 2002). In eastern DRC, protected areassuffered an influx of thousands of miners wishing to exploit the newly lucrative market<strong>for</strong> columbo-tantalite (an ore of tantalum known as coltan). The mining camps subsistedon bushmeat and were responsible <strong>for</strong> decimating the most important population ofEastern lowland gorilla Gorilla beringei graueri (an endemic subspecies) as well asEastern chimpanzees, <strong>for</strong>est elephants, buffalo, antelope and many medium-bodiedspecies (Redmond, 2001; Hayes, 2002). Panic-buying by major companies during theperiod of shortage created temporary stockpiles and reduction in demand/unit price.Some miners have withdrawn but others cannot af<strong>for</strong>d to stop, and it is likely thatbushmeat dependency will increase as the population suffers from chronic poverty(Hayes, 2002). Reports from the Kahuzi-Biega National Park staff indicate that somemining settlements are now cultivating crops in the lowland sector of the park. Thefull extent of the large mammal population crash has yet to be established, becausecontinuing insecurity has prevented surveys (Bernard Iyomi, pers. comm.).Thibault and Blaney (2003) have reported that the oil industry has a significant impacton the bushmeat problem and recruits more people into the <strong>for</strong>est than logging.In 1963, Shell Gabon was granted an exploration permitwithin the Gamba protected areas complex in Gabon. Workerswere recruited nationally, and thousands of people moved tothe area, necessitating the creation of a township within thepark. Bushmeat was exploited to meet the protein demand,and company vehicles, including private jets, were used tosupply outlying urban areas, despite company policies<strong>for</strong>bidding this. In 1986, a collapse in oil prices <strong>for</strong>ced men toreturn to their natal villages, where hunting provided the onlyalternative source of income (Barnes, 2002).The Congo Basin is a likely target <strong>for</strong> further oil exploration,because it holds high-quality petroleum and production costsare low in the region. Currently, oil companies are not requiredto provide the means necessary to mitigate their impact onbiodiversity.THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUE3.3.3 War and civil strifeAccording to the UN Security Council, the illegal mining of coltan (and other naturalresources) has helped support the civil war in DRC, which began in 1996. War affectsbushmeat hunting in a number of ways, not least of which is the increased circulationof weapons and ammunition, which are used successfully <strong>for</strong> hunting. Most soldiers areunpaid and rely on terrorising villagers and traders <strong>for</strong> food. They have been recordedwith live parrots, monkeys and apes on their way to markets (Draulans & VanKrunkelsven, 2002). Refugees may also include armed factions, who practice terrorismand increase pressure on locally available resources as well as <strong>for</strong>ests, which arecleared <strong>for</strong> refugee camps. Harrassment often drives local people into the <strong>for</strong>ests,where they try to make a living from hunting (Draulans & Van Krunkelsven, 2002).Civil unrest in DRC has led to collapse of the transport system due to river and roadblocks, where goods can be confiscated or stolen (Draulans & Van Krunkelsven, 2002).Though it appears that reduced trading opportunities <strong>for</strong> bushmeat leads to huntingbeing abandoned in some areas, there is evidence to suggest that hunting continuesand yields are hidden in the <strong>for</strong>est until such time that trading can resume (Draulans& Van Krunkelsven, 2002).In the proposed Lomako Reserve area of DRC, the ongoing war has led to a decreasein hunting, because villagers are too scared to enter the <strong>for</strong>est, where they riskmeeting soldiers (Dupain et al, 2000).In Liberia, timber and wildlife harvesting have been very poorly regulated since theend of the civil war, when the country has been in social and economic crisis (Hoyt& Frayne, 2003).3.3.4 Weak governance, institutional deficiency and civil disobedienceWeak governance and corrupt administrations are common in areas where bushmeat ishunted. Even where legislation regimes exist, resources and political will to en<strong>for</strong>ce them donot (Kümpel, 2005). Political instability, armed conflict, economic and social strife and AIDShamper state capacity <strong>for</strong> proper management and are significant disincentives <strong>for</strong> wildlifeconservation (CITES, 2000). Wildlife policies are seldom regarded as legitimate, mandatorylaws. Hunters have little fear of breaking the law (Eves et al, 2002), not least becauseofficials themselves often benefit from the trade by accepting bribes (Kümpel, 2005).In 1995, Cameroonian traders licensed by the government were recorded collectingup to 200kg of bushmeat on trips to hunting camps, despite the fact that many of thespecies had been hunted illegally. The government has also been known to suspendclosed hunting seasons to encourage the bushmeat trade (Pearce & Ammann, 1995).Anecdotal evidence also exists of hunters being commissioned by policemen to shootgorillas (WSPA, 1994).29WSPA/APE ALLIANCE28Below:Skull of friendly,habituated gorillakilled <strong>for</strong> bushmeatduring war, Kahuzi-Biega NationalPark, DRC.© Ian Redmond

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVAL3.3.5 Sophistication of hunting techniquesSnaring is currently the cheapest and easiest way to catch wild animals <strong>for</strong> meat; itaccounts <strong>for</strong> 84% of village-based hunting harvests (WCS, 1996). Snaring requires littletime and, compared with hunting with firearms, reduces the risk of apprehension. Butit usually results in more animals being trapped than can be retrieved (Barnett, 2000).Studies have shown that about a quarter of animals trapped by snaring are lost todecomposition or scavengers and a third escape injured (Newing, 2001; Noss, 1998).Snaring is indiscriminate and inevitably affects non-target species. Though carnivoresare often able to chew themselves free, death from residual injuries is probable (Ray,Stein & BCTF, 2002).Firearms have been ubiquitous in <strong>for</strong>ests since colonial times (Barnes, 2002). Theyhave greatly improved hunting success, particularly of arboreal species, such asprimates, which are less easily snared.THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEResearch in the Peruvian Amazon showed no difference in harvests between traditionalhunters using bows and those using shotguns, even though the latter were four timesmore effective (Alvard, 1995). In larger communities, however, overexploitation andthe potential <strong>for</strong> extinction in some species was observed, suggesting that demand,rather than modern technologies, is driving the hunting to crisis state (Bowen-Jones& Pendry, 1999).Table 1 shows the hunting activity and techniques employed by native hunters incapturing wild mammals in central-western Tanzania (December 1995 to February1996) (Carpaneto & Fusari, 2000).3.3.6 Lack of capital or infrastructure <strong>for</strong> domestic meat productionOver the past 30 years, funding <strong>for</strong> agricultural research and development in Centraland West Africa has declined significantly. Over the same period, the US and Australiahave doubled and quadrupled their spending respectively (Milner-Gulland et al, 2003).Forest-dwellers are often hostile to the idea of livestock farming (CITES, 2004),because the costs involved are far more prohibitive than those incurred by commercialbushmeat hunters, who are able to avoid paying <strong>for</strong> animal husbandry, veterinary care,transport, slaughter and certification (Born Free, 2004). Moreover, agricultural marketspromote unfair prices, and rural communities often lack the skills or resources tonegotiate trade practices more favourable to their needs (ABCG, 2004).In Asia, bushmeat is generally a luxury <strong>for</strong> wealthy city-dwellers; rural people haveturned to domestic meat to compensate <strong>for</strong> the lack of wild species (Kümpel, 2005).31WSPA/APE ALLIANCE30Left: Dikdikcaught in snareand Right:Bushmeat drying,Tsavo NationalPark, Kenya.Taxonomic group Guns Traps Spears Dogs Total %Insectivors – 9 – 1 10 4.23Nocturnal Primates – 2 – – 2 0.84Diurnal Primates 6 1 4 3 14 5.93Carnivora 22 8 4 20 54 22.88Hyracoidea 1 – – 1 2 0.84Suidae 7 – 5 – 12 5.08Hippopotamidae 1 – – – 1 0.42Bovidae 82 9 10 3 104 44.06Pholidota – 1 – 1 0.42Rodenta 6 6 2 3 17 7.20Lagomorpha 2 10 – 7 19 8.05Total 127 45 26 38 236 100% 53.81 19.06 11.01 16.1 100Table 1: Numberof specimens <strong>for</strong>each taxonomicgroup killed bynative huntersduring the studyperiod in centralwesternTanzania(Source:Carpaneto &Fusari, 2000)© David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust© www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALIt is unlikely that this opportunity will be available to Africans faced with a shortage of<strong>for</strong>est wildlife. As well as problems of low agricultural productivity (due to poor soils,prevalence of disease and frequent wars), African <strong>for</strong>est-dwellers have lower accessthan Asians to coastline and fish supplies (Kümpel, 2005).3.3.7 Changes in the cultural environment and discarding ofsocial taboos and traditional hunting embargoesThe continuous, year-round demand <strong>for</strong> bushmeat has gradually eradicated traditionalhunting seasons, and wildlife no longer benefits from recovery periods during closedseasons (Barnett, 2000). Moreover, gender selection and embargoes on pregnantindividuals, as well as traditional taboo and totem restrictions are being abandonedin favour of maintaining supply (Barnett, 2000).Bushmeat represents a coping mechanism during periods of prolonged drought andfamine, when domestic stocks are likely to have perished and horticultural produce isscarce (Merode et al, 2004). Wild animals become more nomadic as they search <strong>for</strong>water and are easier to locate in the typically thinner vegetation (Barnett, 2000).Thus, bushmeat hunting can be seasonally acute.3.3.8 Structural adjustment plans imposed by internationalfinancial institutions resulting in civil service job lossesWhilst hunting is a traditional way of life <strong>for</strong> some people, many commercial bushmeathunters in Africa have turned to hunting after being made redundant. This has beenobserved in countries <strong>for</strong>ced to slim down the civil service to curb governmentspending. With family responsibilities, there are few opportunities <strong>for</strong> alternativeemployment and many have turned to commercial hunting because it is profitableand requires little capital to start a business.3.3.9 Unemployment, poverty and dysfunctional economies,with lack of alternative monetary opportunitiesThis has been discussed in section 3.2.3.4 The effects of bushmeat hunting on speciesand ecosystemsA list of species worldwide recorded as being hunted <strong>for</strong> bushmeat is included asAppendix 1 (see separate document). Figure 1 and Graphs 1 and 2 respectivelysummarise the taxonomic composition of species hunted internationally <strong>for</strong> bushmeat,the number of species hunted <strong>for</strong> bushmeat per geographic region, and the number ofspecies hunted <strong>for</strong> bushmeat per taxa per geographic region.THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUE33WSPA/APE ALLIANCE328007006005004003002001000Insecta 45%Mammalia 23% Aves 20%Reptiles6%Amphibia6%Figure 1:Taxonomiccomposition ofspecies huntedinternationally <strong>for</strong>bushmeatCarribbean Islands Asia Europe Latin America Africa North America OceaniaRegionGraph 1: Numberof species hunted<strong>for</strong> wild meat pergeographic regionNumber of species

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVAL3.4.1 Importance of <strong>for</strong>est wildlifeInvertebrates, amphibians, insects, fish, reptiles, birds and mammals are all targetedby the bushmeat trade. Forest animals are ecologically fundamental, and many <strong>for</strong>estplants – some of which are economically valuable – are reliant on herbivory andpredation practices <strong>for</strong> pollination, seed dispersal and germination (Williamson, 2001;Serio-Silva & Rico-Gray, 2002; Riley, 2002).In Gabon, regeneration of tree species such as Irvingia gabonensis and Tieghemella sp. islow in areas where animals responsible <strong>for</strong> dipersing their seeds are rare (Medou, 2001).Large-bodied frugivores, the seed dispersal agents of plants with large fruits are chieftargets of bushmeat hunters. Moore (2001) showed that Inga ingoides trees in Bolivia hadsignificantly lower genetic diversity in areas where there sole seed vectors (Spidermonkeys) had been driven to extinction.150 species of fruit among the rumen contents of duikers suggests that they arecrucial <strong>for</strong> seed dispersal (Eves, Stein & BCTF, 2002). Up to 80% of all tree speciescould have their seed dispersal affected by the loss of tropical <strong>for</strong>est frugivores(Peres & van Roosmalen, 2002, cited by Apaza et al, 2002).Over-exploitation of wildlife is expected to alter <strong>for</strong>est composition, architecture andbiomass, as well as altering ecosystem dynamics, such as regrowth and successionpatterns, deposition of soil nutrients and carbon sequestration (Apaza et al, 2002).The ‘empty <strong>for</strong>est syndrome’ there<strong>for</strong>e threatens thefuture not only of species but also of the ecosystemas a whole.3.4.2 Species vulnerabilityResearch suggests that bushmeat use is positivelycorrelated with availability, the most commonly huntedspecies being those that are abundant, proximal tohuman habitation and commonly regarded as pests(Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999). Habitat type andlocation are also crucial factors; bushmeatconsumption is more prevalent in <strong>for</strong>est communitiesthan in any other type of habitat (see Graph 3), despiteevidence that tropical <strong>for</strong>ests are relativelyunproductive compared to other habitat types (Kümpel,2005). In agricultural park-boundary areas, whereonly small game is present, the loss from cropraiding can exceed the gain from bushmeat hunting (Naughton-Treves et al, 2003).The most profitable species to hunt are large-bodied animals, weighing more than1kg (<strong>for</strong> example, apes and duikers), which provide more meat per gun cartridge thansmaller species (Kaul et al, 1994; Robinson, 1995). Concurrently, large-bodied animalsare also the most vulnerable to hunting due to their low reproductive rates (Barnes,2002). Even when the most productive species to hunt become scarce, hunting will7654321ForestMosaicSavannaMangrove035RodentsMonkeysAntelopesPangolinsWild birdsSnakesWild pigs & hippoWild catsSnailsChimpanzeesInsectsElephantsGorillasBatsTaxaWSPA/APE ALLIANCEAverage number of meals per person per month600500400300Number of species© Ian Redmond200AmphibiaAvesMammaliaReptilesInsectsAll1000Carribbean IslandsEast AsiaEuropeMesoAmericaNorth AfricaNorth AmericaNorth AsiaOceaniaSouth AmericaSouth and SE AsiaSouth and SW AsiaSub-Saharan AfricaWest/Central Asia34RegionGraph 2: Numberof species hunted<strong>for</strong> wild meat pertaxa pergeographic regionleft Graph 3:Consumption ofbushmeat taxa byhabitat (Source:Wolfe, 2004)THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUEBelow: Mbinzo(smoked caterpillars):nutritious, legalbushmeat <strong>for</strong> sale inKinshasa, DRC.

WSPA/APE ALLIANCERECIPES FOR SURVIVALstill be profitable, because small-bodied species will remain common (Fa et al, 2001).The opportunistic nature of hunting keeps pressure on large animals high andaccelerates their extinction (Barnes, 2002; Wilkie and Carpenter, 1999).The vulnerability of a species to hunting is, there<strong>for</strong>e, a product of biologicalcharacteristics, including size, growth rate and reproductive biology, as well asdemographic factors, including population density, distribution and habitat specificity.3.4.3 Geographic repercussionsHunting of wild animals <strong>for</strong> meat is not just an African problem. Twenty-five tonnes of turtlesare exported every week from Sumatra, Indonesia, 1,500 <strong>for</strong>est rats are sold per week in aSulawesi market and 28,000 primates are hunted annually in Loreto, Peru (Milner-Gulland etal, 2003). Referring to wild meat rather than bushmeat reflects the global nature of thisissue. Preliminary research presented in Appendix 1 suggests that 27% of Latin Americanmammals, 50% of Asian mammals and 50% of African mammals recorded amongstbushmeat harvests are categorised as endangered or vulnerable to extinction.The status of many <strong>for</strong>est species is difficult to determine by traditional censustechniques (Ray, Stein & BCTF, 2002). Annual variations mean that accurate estimatescan be made only by several surveys over consecutive years (Barnes, 2002).Table 2:Composition ofbushmeatcaptured in theCongo Basin(Source: Wilkie &Carpenter, 1999)Species loss occurred in Asia first. Many species have been hunted to extinction,including 12 species of mammal in Vietnam since 1975 (Whitfield, 2003). Bushmeatis still consumed in large quantities throughout Asia (Kümpel, 2005). In Indonesia, thetrade in babirusa is purely commercial, with no subsistence motivation at all (Milner-Gulland & Clayton, 2002).In Central Africa, hunting pressure has been specifically identified as a threat to 84Location Ungulates a Primates Rodents OtherInturi <strong>for</strong>est, DRC 1 60 – 95% 5 – 40% 1% 1%Makokou, Gabon 2 58% 19% 14% 9%Diba, Congo 3 70% 17% 9% 4%Ekom, Cameroon 4 85% 4% 6% 5%Brazzaville, Congo 13 76% 8% 6% 10%Ouesso, Congo 5 57% 34% 5% 4%Ndoki and Ngatongo, Congo 6 81 – 87% 11 – 16% 2 – 3% 2 – 3%Dzanga-Sangha, CAR 7 77 – 86% 0% 11 – 12% 2 – 12%Libreville, Port Gentil, Oyem, and Makokou, Gabon 8 34 – 61% 20 – 45% 5 – 27% 3 – 12%Bioko and Rio Muni, Equatorial Guinea 9 36 – 43% 23 – 25% 31 – 37% 2 – 4%Dja, Cameroon 12 88% 3% 5% 4%Ekom, Cameroon 10 87% 1% 6% 6%Oleme, Congo 11 62% 38%THE BROADER BUSHMEAT ISSUESpecies Hunted individuals/km 2 Unhunted individuals/km 2 ImpactCephalophus sylvicultur 0 0.03 -100%Gorilla gorilla 0 0.24 -100%Cercocebus albigena 2.5 51.2 -95%Pan troglodytes 0.03 0.36 -92%Cephalophus callipygus 0.6 6.7 -91%Clolbus abyssinicus 0.8 6.8 -88%Tragelaphus spekei 0.005 0.03 -83%Potamochoerus porcus 0.36 1.7 -79%Hyemoschus aquaticus 0.02 0.09 -78%Cercopithecus nictitans 21.9 80.2 -73%Cephalophus dorsalis 2.5 5.8 -57%Cercopithecus pogonias 11.1 19.8 -44%Cercopithecus cephus 12.5 22 -43%Cephalophus monticola 30.4 53 -43%mammalian species and subspecies (IUCN, 2000) (see Tables 2 and 3). Thirty-fourspecies are listed as threatened by extinction, the majority of which are primates (17),and the rest duikers (12), carnivores (4) and rodents (1) (CITES, 2004). Localextinctions have been recorded in populations of leopard Panthera pardus, golden catProfelis aurata and elephant Loxodonta africana, with similar declines expected <strong>for</strong>giant pangolins Smutsia gigantaea and slender-snouted crocodiles Crocodyluscataphractus (various authors cited by Bowen-Jones & Pendry, 1999).Commercial bushmeat hunting in West Africa has already caused local extinctions(BCTF, 2000a).Table 3:Bushmeat speciesdensities in huntedand unhunted<strong>for</strong>est in theCongo Basin(Source: Wilkie &Carpenter, 1999)Kenya provides a model <strong>for</strong> East Africa, where wildlife populations have declined by58% over the past 20 years and the scale of hunting appears to be escalating (BornFree, 2004). Decreasing wildlife populations have intensified hunting ef<strong>for</strong>t,necessitating more sophisticated and unsustainable methods, such as night torchhunting (Barnett, 2000).According to a recent comparative study of 57 and 31 mammalian taxa in the Congoand Amazon Basins respectively, 60% of Congo animals were exploited unsustainably,compared with no Amazon species (Fa et al, 2002). This research also showed that Congomammals must annually produce 93% of their body mass to balance extraction rates,whereas Amazon species need only produce 4%. Conversely, studies in 25 Amazonian<strong>for</strong>est sites showed that even small-scale subsistence hunting reduced the number oflarge-bodied game species (Peres, 2000). Milner-Gulland et al (2003) assert that we canexpect extinctions in even the remote areas of Latin America in the next 10 – 20 years.37WSPA/APE ALLIANCE36