3S9rydC3U

3S9rydC3U

3S9rydC3U

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

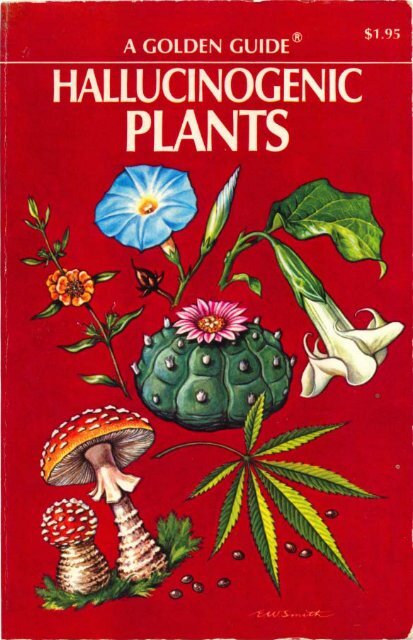

HALLUCINOGENICPLANTSbyRICHARD EVANS SCHULTESIllustrated byELMER W. SMITH® GOLDEN PRESS • NEW YORKWestern Publishing Company, Inc.Racine, Wisconsin

WHAT AREHALLUCINOGENIC PLANTS?In his search for food, early man tried all kinds of plants.Some nourished him, some, he found, cured his ills, andsome killed him. A few, to his surprise, had strangeeffects on his mind and body, seeming to carry him intoother worlds. We call these plants hallucinogens, becausethey distort the senses and usually produce hallucinations-experiences that depart from reality. Although mosthallucinations are visual, they may also involve the sensesof hearing, touch, smell, or taste-and occasionallyseveral senses simultaneously are involved .The actual causes of such hallucinations are chemicalsubstances in the plants. These substances are true narcotics.Contrary to popular opinion, not all narcotics aredangerous and addictive. Strictly and etymologicallyspeaking, a narcotic is any substance that has a depressiveeffect, whether slight or great, on the centralnervous system.Narcotics that induce hallucinations are variouslycalled hallucinogens (halluCination generators), psychotomimetics(psychosis mimickers), psychotaraxics(mind disturbers), and psychedelics (mind manifesters).No one term fully satisfies scientists, but hallucinogenscomes closest. Psychedelic is most widely used inthe United States, but it combines two Greek rootsincorrectly, is biologically unsound, and has acquiredpopular meanings beyond the drugs or their effects.In the history of mankind, hallucinogens have probablybeen the most important of all the narcotics. Theirfantastic effects made them sacred to primitive man andmay even have been responsible for suggesting to himthe idea of deity.5

RiveacarymbasaNicotianatabacumStatue of Xochipilli, the Aztec "Prince of Flowers," unearthed inTlalmanalca on the slopes of the volcano Popocatepetl and now ondisplay in the Museo Nacional in Mexico City. Labels indicateprobable botanical interpretation of stylized glyphs.8

USE IN MODERN WESTERN WORLDOur modern society has recently taken up the use,sometimes illegally, of hallucinogens on a grand scale.Many pe·ople believe they can achieve "mystic" or"religious" experience by altering the chemistry of thebody with hallucinogens, seldom realizing that they aremerely reverting to the age-old practices of primitivesocieties. Whether drug-induced adventures can be

PTERIDOPHYT ABRYOPHYTADISTRIBUTION OF HALLUCINOGENSThe majority of hallucinogenic species occur amongthe highly evolved flowering plants and in onedivision (fungi) of the simpler, spore-bearing plants.No hallucinogenic species are yet known from theother "branches" of the plant kingdom (see pp. 12-13). Plants illustrated are representative psychoactivespecies.14

CHEMICAL COMPOSITIONHallucinogens are limited to a small number of typesof chemical compounds. All hallucinogens found in plantsare organic compounds-that is, they contain carbonas an essential part of their structure and were formedin the life processes of vegetable organisms. No inorganicplant constituents, such as minerals, are known to havehallucinogenic effects.Hallucinogenic compounds may be divided convenientlyinto two broad groups: those that contain nitrogenin their structure and those that do not. Those withnitrogen are far more common. The most important ofthose lacking nitrogen are the active principles of marihuana,terpenophenolic compounds classed as dibenzopyransand called cannabinols-in particular, tetrahydrocannabinols.The hallucinogenic compounds with nitrogenin their structure are alkaloids or related bases."THC"A1-TETRAHYDROCANNABINOLcarbon atomQl hydrogen atoma oxygen atom16

pounds that act on various parts of the body so feware hallucinogenic. The indole nucleus of the hallucinogensfrequently appears in the form of tryptamine derivatives.It is composed of phenyl and pyrrol segments (see diagramon opposite page).Tryptamines may be "simple" -that is, without substitutions-orthey may have various "side chains" knownas hydroxy (OH), methoxy (Oh), or phosphogloxy(OP03H) groups in the phenyl ring.The indole ring (shown in red in the diagram) is evidentnot only in the numerous tryptamines (dimethyltryptamine,etc.) but also in the various ergoline alkaloids{ergine and others), in the ibogaine alkaloids, and in the,8-carboline alkaloids (harmine, harmaline, etc.). lysergicacid diethylamide (lSD) has an indole nucleus. Onereason for the significance of the indolic hallucinogensmay be their structural similarity to the neurohumoraltryptamine serotonin (5-hydroxydimethyltryptamine), presentin the nervous tissue of warm-blooded animals.Serotonin plays a major role in the biochemistry of thecentral nervous system. A study of the functioning ofhallucinogenic tryptamine may experimentally help toexplain the function of serotonin in the body.A chemical relationship similar to that between indolichallucinogens and serotonin exists betweenmescaline, an hallucinogenic phenylethylamine base inpeyote, and the neurohormone norepinephrine.These chemical similarities between hallucinogenic compoundsand neurohormones with roles in neurophysiologymay help to explain hallucinogenic activity and evencertain processes of the central nervous system. Otheralkaloids-the isoquinolines, tropanes, quinolizidines, andisoxazoles-are more mildly hallucinogenic and mayoperate differently in the body.18

HALLUCINOGENIC ALKALOIDS WITHTHE INDOLE NUCLEUS(CH2h - N (CH3hHN,N = DimethyltryptamineHSerotoninHarmalineTHE INDOLE RING®(CH2h-NH (CH3)2HPsilocybinHErgine

PSEUDOHALLUCIN OGEN SThese are poisonous plant compounds that cause whatmight be called secondary hallucinations or pseudohallucinations.Though not true hallucinogenic agents,they so upset normal body functions that they inducea kind of delirium accompanied by what to all practicalpurposes are hallucinations. Some components ofthe essential oils-the aromatic elements responsiblefor the characteristic odors of plants-appear to actin this way. Components of nutmeg oil are an example.Many plants having such components are extremely dangerousto take internally, especially if ingested in doseshigh enough to induce hallucinations. Research has notyet shed much light on the kind of psychoactivity producedby such chemicals.Myristico frogrons isthe source of nutmegand mace.20Nepeto catariais known for itsstimulatingeffect on cots.

HOW HALLUCINOGENS ARE TAKENHallucinogenic plants are used in a variety of ways,depending on the kind of plant material, on the activechemicals involved, on cultural practices, and on otherconsiderations. Man, in primitive societies everywhere,has shown great ingenuity and perspicacity in bendinghallucinogenic plants to his uses.PLANTS MAY BE EATEN, eitherfresh or dried, as are peyoteand teonanacatl; or juice fromthe crushed leaves may be drunk,as with Salvia divinorum (inMexico). Occasionally a plantderivative may be eaten, as withhasheesh. More frequently, abeverage may be drunk:ayahuasca, caapi, or yaje fromthe bark of a vine; the SanPedro cactus; jurema wine; ibaga;. leaves of toloache; or crushedseeds from the Mexican morningglories. Originally peculiar toNew World cultures, where itwas one way of using tobacco,smoking is now a widespreadmethod of taking cannabis. Narcoticsother than tobacco, suchas tupa, may also be smoked.SNUFFING is a preferred methodfor using several hallucinogens-yopo, epena, sebil, rape dosindios. like smoking, snuffingis a New World custom. A fewNew World Indians have takenhallucinogens rectally-as inthe case of Anadenanthera.One curious method of inducingnarcotic effects is theAfrican custom of incising thescalp and rubbing the juice fromthe onionlike bulb of a speciesof Pancratium across the incisions.This method is a kindof primitive counterpart of themodern hypodermic method.Several methods may be usedin the case of some hallucinogenicplants. Virola resin, forexample, is licked unchanged, isusually prepared in snuffform, is occasionally made intopellets to be eaten, and maysometimes be smoked .PLANT ADDITIVES or admixturesto major hallucinogenicspecies are becoming increasinglyimportant in research.Subsidiary plants are sometimesadded to the preparation toalter, increase, or lengthen thenarcotic effects of the mainingredients. Thus, in making theayahuasca, caapi, or yajedrinks, prepared basically fromBanisteriopsis caapi or B.inebrians, several additives areoften thrown in: leaves ofPsychotria viridis or Banisteriopsisrusbyana, which themselves containhallucinogenic tryptamines;or Brunfelsia or Datura, both ofwhich are hallucinogenic in theirown right.21

OLD WORLD HALLUCINOGENSExisting evidence indicates that man in the Old World-Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia-has made lessuse of native plants and shrubs for their hallucinogenicproperties than has man in the New World.There is little reason to believe that the vegetation ofone half of the globe is poorer or richer in species withhallucinogenic properties than the other half. Why, then,should there be such disparity? Has man in the OldWorld simply not discovered many of the native hallucinogenicplants? Are some of them too toxic in otherways to be utilized? Or has man in the Old World beenculturally less interested in narcotics? We have no realanswer. But we do know that the Old World has fewerknown species employed hallucinogenically than does theNew World: compared with on ly 15 or 20 species used inthe Eastern Hemisphere, the species used hallucinogenicallyin the Western Hemisphere number more than 1 00!Yet some of the Old World hallucinogens today holdplaces of primacy throughout the world. Cannabis,undoubtedly the most widespread of all the hallucinogens,is perhaps the best example. The several solanaceousingredients of medieval witches' brews-henbane, nightshade,belladonna, and mandrake-greatly influencedEuropean philosophy, medicine, and even history for manyyears. Some played an extraordinarily vital religiousrole in the early Aryan cultures of northern India.The role of hallucinogens in the cultural and socialdevelopment of many areas of the Old World is onlynow being investigated. At every turn, its extent anddepth are becoming more evident. But much moreneeds to be done in the study of hallucinogens andtheir uses in the Eastern Hemisphere.22

Amanita muscariavariantyellow formwhitespores,greatlyenlargedyoung"button"stage23

FLY AGARIC MUSHROOM, Amanita muscaria, may beone of man's oldest hallucinogens. It has been suggestedthat perhaps its strange effects contributed toman's early ideas of deity.Fly agaric mushrooms grow in the north temperate regionsof both hemispheres. The Eurasian type has abeautiful deep orange to blood-red cop flecked withwhite scales. The cop of the usual North Americantype varies from cream to on orange-yellow. There orealso chemical differences between the two, for the NewWorld type is devoid of the strongly hallucinogeniceffects of its Old World counterpart.The use of this mushroom as on orgiastic and shamanisticinebriant was discovered in Siberia in 1730. Subsequently,its utilization has been noted among severalisolated groups of Finno-Ugrion peoples (Ostyak andVogul) in western Siberiaand three primitive tribes(Chuckchee, Koryok, andKomchodol) in northeasternSiberia. These tribeshod no other intoxicantuntil they learned recentlyof alcohol.These Siberians ingestthe mushroom alone, eithersun-dried or toasted slowlyover a flre, or they maytoke it in reindeer milkor with the juice of wildplants, such as a speciesAmanita muscaria typically occursin association with birches.

A Siberian Chukchee man with wooden urine vessel, about to recycleand extend intoxication from Amanita muscaria.of Vaccinium and a species of Epilobium. When eatenalone, the dried mushrooms are moistened in themouth and swallowed, or the women may moisten androll them into pellets for the men to swallow.A very old and curious practice of these tribesmenis the ritualistic drinking of urine from men whohave become intoxicated with the mushroom. The activeprinciples pass through the body and are excretedunchanged or as still active derivatives. Consequently,a few mushrooms may inebriate many people.The nature of the intoxication varies, but one orseveral mushrooms induce a condition marked usuallyby twitching, trembling, slight convulsions, numbness ofthe limbs, and a feeling of ease characterized by happiness,a desire to sing and dance, colored visions,and macropsia (seeing things greatly enlarged). Violencegiving way to a deep sleep may occasionally occur. Participantsare sometimes overtaken by curious beliefs,25

such as that experienced by an ancient tribesman whoinsisted that he had just been born! Religious fervoroften accompanies the inebriation.Recent studies suggest that this mushroom was themysterious God-narcotic soma of ancient India. Thousandsof years ago, Aryan conquerors, who sweptacross India, worshiped soma, drinking it in religiousceremonies. Many hymns in the Indian Rig-Veda are devotedto soma and describe the plant and its effects.The use of soma eventually died out, and its identityhas been an enigma for 2,000 years. During the pastcentury, more than 100 plants have been suggested,but none answers the descriptions found in the manyhymns. Recent ethnobotanical detective work, leadingto its identification as A. muscaria, is strengthened bythe reference in the vedas to ceremonial urine drinking,since the main intoxicating constituent, muscimole (knownHOller\1, 0 _/-- H-coo -co2Ell NH3. H20 -H20lbotenic AcidMuscimoleH O=C, __/-CH-C0080 IEll NH3MuscazoneChemical formulas ofthe important Amanitamuscaria alkaloids.26

only in this mushroom), is the sole natural hallucinogenicchemical excreted unchanged from the body.Only in the last few years, too, has the chemistryof the intoxicating principle been known. For a century,it was believed to be muscarine, but muscarine is presentin such minute concentrations that it cannot act as theinebriant. It is now recognized that, in the drying orextraction of the mushrooms, ibotenic acid forms severalderivatives. One of these is muscimole, the mainpharmacologically active principle. Other compounds,such as muscazone, are found in lesser concentrationsand may contribute to the intoxication.Fly agaric mushroom is so called because of its ageolduse in Europe as a fly killer. The mushrooms wereleft in an open dish. Flies attracted to and settling onthem were stunned, succumbing to the insecticidalproperties of the plant. ARCTIC OCEAN. . ,..Birches and Pines- Chukchee-Koryok peoples- Uralic peoples (Ostyok, Vogul, etc.Mop of northern Eurasia shows regions of birches and pines, whereAmanita muscorio typically grows, and areas inhabited by ethnic groupsthat use the mushroom as on hallucinogen.27

AGARA (Galbulimima Belgraveana) is a tall forest treeof Malaysia and Australia. In Papua, natives make adrink by boiling the leaves and bark with the leavesof ereriba. When they imbibe it, they become violentlyintoxicated, eventually falling into a deep sleep duringwhich they experience visions and fantastic dreams.Some 28 alkaloids have been isolated from this tree, andalthough they are biologically active, the psychoactiveprinciple is still unknown. Agora is one of four speciesof Galbulimima and belongs to the Himantandraceae,a rare family related to the magnolias.ERERIBA, an undetermined species of Homo/omena, isa stout herb reported to have narcotic effects when itsleaves are taken with the leaves and bark of agara.The active chemical constituent is unknown. Ereriba is amember of the aroid family, Araceae. There are some140 species of Homo/omena native to tropical Asiaand South America.GalbulimimaHomalomenalauterbachii

Bushman applyingPancrotium bulbto scalp incisions.KWASHI (Pancratium trianthum) is considered to bepsychoactive by the Bushmen in Dobe, Botswana. Thebulb of this perennial is reputedly rubbed over incisionsin the head to induce visual hallucinations. Nothing isknown of its chemical constitution. Of the 14 other speciesof Pancratium, mainly of Asia and Africa, manyare known to contain psychoactive principles, mostlyalkaloids. Some species are potent cardiac poisons.Pancratium belongs to the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae.GALANGA or MARABA (Kaempferia galanga) is anherb rich in essential oils. Natives in New Guinea eatthe rhizome of the plant as an hallucinogen. It is valuedlocally as a condiment and, like others of the 70species in the genus, it is used in local folk medicine tobring boils to a head and to hasten the healing of burnsand wounds. It is a member of the ginger family, Zingiberaceae.Phytochemical studies have revealed nopsychoactive principle.29

Hemp field in Afghanistan, showing portly harvested crop of the short,conical Cannabis indica grown there.MARIHUANA, HASHEESH, or HEMP (species of thegenus Cannabis), also called Kif, Bhang, or Charas, isone of the oldest cultivated plants. It is also one of themost widely spread weeds, having escaped cultivation,appearing as an adventitious plant everywhere,except in the polar regions and the wet, forested tropics.Cannabis is the source of hemp fiber, an ediblefruit, an industrial oil, a medicine, and a narcotic. Despiteits great age and its economic importance, the plantis still poorly understood, characterized more by whatwe do not know about it than by what we know.Cannabis is a rank, weedy annual that is extremelyvariable and may attain a height of 18 feet. Flourishingbest in disturbed, nitrogen-rich soils near human habitations,it has been called a "camp follower," going withman into new areas.It is normally dioecious-that is, the male and femaleparts are on different plants. The male or staminateplant is usually weaker than the female or pistillateplant. Pistillate flowers grow in the leaf axils. Theintoxicating constituents are normally concentrated in aresin in the developing female flowers and adjacentleaves and stems.30

CLASSIFICATION OF CANNABIS is disputed bybotanists. They disagree about the family to which itbelongs and also about the number of species. Theplant is sometimes placed in the fig or mulberry family(Moraceae) or the nettle family (Urticaceae ), but it isnow usually separated, together with the hop plant(Humulus), into a distinct family: Cannabaceae.It has been widely thought that there is one species,Cannabis sativa, which, partly as a result of selectionby man, has developed many "races" or "varieties,"for better fiber, for more oil content, or for. strongernarcotic content. Selection for narcotic activity has beenespecially notable in such areas as India, where intoxicatingproperties have had religious significance. Environmentalso has probably influenced this biologicallychangeable species, especially for fiber excellence andnarcotic activity. Current research indicates that theremay be other species: C. indica and C. ruderalis. AllCannabis is native to central Asia.Cannabis leaves ore palmately divided-normally into 3-7 leaflets,occasionally into 11- 13. Leaflets vary in length from 2 to 6 inches.

MARIHUANACannabis sativaseedling/

Chinese characters T A MA, theoldest known name far cannabis.;k =TA (pronounced DA).Literally this means an adultman, and by extension maysignify great or tall.J#. =MA. It represents afiber plant, literally a clump ofplants ( ), growing near adwelling (} ). Hence, thetwo symbols together mean"the tall fiber plant,"which everywhere inChina signifies cannabis.HISTORY OF CANNABIS USE dates to ancient times.Hemp fabrics from the late 8th century B.C. havebeen found in Turkey. Specimens have turned up inan Egyptian site nearly 4,000 years of age. In ancientThebes, the plant was made into a drink with opiumlikeeffects. The Scythians, who threw cannabis seedsand leaves on hot stones in steam baths to producean intoxicating smoke, grew the plant along the Volga3,000 years ago.Chinese tradition puts the use of the plant back4,800 years. Indian medical writing, compiled before1000 B.C., reports therapeutic uses of cannabis. Thatthe early Hindus appreciated its intoxicating propertiesis attested by such names as "heavenly guide" and"soother of grief." The Chinese referred to cannabisas "liberator of sin" and "delight giver." The Greekphysician Galen wrote, about A.D. 160, that general34

use of hemp in cakes produced narcotic effects. In 1 3thcenturyAsia Minor, organized murderers, rewarded withhasheesh, were known as hashishins, from which maycome the term assassin in European languages.Hemp as a source of fiber was introduced by thePilgrims to New England and by the Spanish and Portugueseto their colonies in the New World.Objects connected with the useof cannabis were found in frozentombs of the ancient Scythians,in the Altai Mountains on theborder between Russia and OuterMongolia.The small, tepee-like structurewas covered with a felt orleather mat and stood over thecopper censer (four-legged stoollikeobject). Carbonized hempseeds were found nearby. Thetwo-handled pot contained cannabisfruits. The Scythian customof breathing cannabis fumesin the steam bath was mentionedabout 500 B.C. by theGreek naturalist Herodotus.35

THE MEDICINAL VALUE OF CANNABI S has beenknown for centuries. Its long history of use in folk medicineis significant, and it has been included more recentlyin Western pharmacopoeias. It was listed in theUnited States Pharmacopoeia until the 1930's as valuable,especially in the treatment of hysteria. The progressmade in modern research encourages the belief thatso prolific a chemical factory as Cannabis may indeedoffer potential for new medicines.THE CHEMISTRY OF CANNABIS is complex. Many organiccompounds have been isolated, some with narcoticproperties and others without. A fresh plantyields mainly cannabidiolic acids, precursors of thetetrahydrocannabinols and related constituents, such ascannabinol, cannabidiol, tetrahydrocannabinol-carboxylicacid, stereaisomers of tetrahydrocannabinol, and cannabichromene.It has been demonstrated recently that the main effectsare attributable to delta-1 -tetrahydrocannabinol. Thetetrahydrocannabinols, which form an oily mixture ofseveral isomers, are non-nitrogenous organic compoundsderived from terpenes (see page 16). They arenot alkaloids, although traces of alkaloids have beenreported in the plant.Until recently, little was known about the effects ofpure tetrahydrocannabinol on man. Controlled studiesare basic to any progress. These are now possible withthe recent synthesis of the compound, a major advancein studying the mechanism of physiological activity of thisintoxicant. Because the crude cannabis preparationsnormally used as a narcotic vary greatly in their chemicalcomposition, any correlations of their biologicalactivity would be relatively meaningless.36

three contemporary designssilver hookahfrom IndioAssortment of cannabis pipes and water pi pes.METHODS OF USING CANNABIS vary. In the NewWorld, marihuana ( maconha in Brazil) is smoked-thedried, crushed flowering tips or leaves, often mixedwith tobacco in cigarettes, or ''reefers.'' Hasheesh, theresin from the female plant, is eaten or smoked, oftenin water pipes, by millions in Moslem countries ofnorthern Africa and western Asia. In Afghanistan andPakistan, the resin is commonly smoked. Asiatic Indiansregularly employ three preparations narcotically: bhangconsists of plants that are gathered green, dried, andmade into a drink with water or milk or into a candy(majun) with sugar and spices; charas, normally smokedor eaten with spices, is pure resin; ganjah, usually smoked38

with tobacco, consists of resin-rich dried tops from thefemale plant. Many of these unusually potent preparationsmay be derived from C. indica.NARCOTIC USE OF CANNABIS has grown in popularityin the past 40 years as the plant has spread tonearly all parts of the globe. The narcotic use ofcannabis in the United States dates from the 1920'sand seems to have started in New Orleans and vicinity.Increase in the plant's use as an inebriant inWestern countries, especially in urban centers, has ledto major problems and dilemmas for European andAmerican authorities. There is a sharp division ofopinion as to whether the widespread narcotic use ofcannabis is a vice that must be stamped out or is aninnocuous habit that should be permitted legally. Thesubject is debated hotly, usually with limited knowledge.We do not yet have the medical, social, legal, and moralinformation on which to base a sound judgment. Asone writer has said, the marihuana problem needs"more light and less heat." Controlled, scientificallyvalid experiments with cannabis, involving large numbersof individuals, have not as yet been made.Contemporary American cannabis shoulder patches.

EFFECTS OF CANNABIS, even more than of otherhallucinogens, are highly variable from person to personand from one plant strain to another. This variabilitycomes mainly from the unstable character of someof the constituents. Over a period of time, for example,the inactive cannabidiolic acid converts to active tetrahydrocannabinolsand eventually to inactive cannabinol,such chemical changes usually taking place more rapidlyin tropical than in cooler climates. Material from plantsof different ages may thus vary in narcotic effect.The principal narcotic effect is euphoria. The plantis sometimes not classified as hallucinogenic, and it istrue that its characteristics are not typically psychotomimetic.Everything from a mild sense of ease andwell-being to fantastic dreams and visual and auditoryhallucinations are reported. Beautiful sights, wonderfulmusic, and aberrations of sound often entrance themind; bizarre adventures to fill a century take place ina matter of minutes.Soon after taking the drug, a subject may find himselfin a dreamy state of altered consciousness. Normalthought is interrupted, and ideas are sometimes plenti-In many parts of Asia theuse of cannabis preparationsis both socially and legallyacceptable. In predominantlyMoslem countries, cannabis isusually smoked in water pipes,sometimes called hookahs.The illustration shows anAfghani using one of themany kinds of water pipesseen in Asia.

Market forms of cannabis include finely ground or "manicured"marihuana, "reefers" (smaller than commercial tobacco cigarettes),pure hasheesh, and compressed kilo bricks.ful, though confused. A feeling of exaltation and innerjoy may alternate, even dangerously, with feelings ofdepression, moodiness, uncontrollable fear of death,and panic. Perception of time is almost invariablyaltered. An exaggeration of sound, out of all relation tothe real force of the sound emitted, may be accompaniedby a curiously hypnotic sense of rhythm. Although theoccasional vivid visual hallucinations may have sexualcoloring, the often-reported aphrodisiac properties ofthe drug have not been substantiated.Whether cannabis should be classified primarily as astimulant or depressant or both has never been determined.The drug's activities beyond the central nervoussystem seem to be secondary. They consist of a rise inpulse rate and blood pressure, tremor, vertigo, difficultyin muscular coordination, increased tactile sensitivity,and dilation of the pupils.Although cannabis is definitely not addictive, psychologicaldependence may often result from continualuse of the drug.41

TURKESTAN MINT (Lagochilus inebrians) is a small shrubof the dry steppes of Turkestan. For centuries it hasbeen the source of an intoxicant among the Tajik,Tartar, Turkoman, and Uzbek tribesmen. The leaves,gathered in October, are toasted, sometimes mixedwith stems, fruits, and flowers. Drying and storage increasetheir aromatic fragrance. Honey and sugar areoften added to reduce their intense bitterness.Valued as a folk medicine and included in the 8thedition of the Russian pharmacopoeia, it is used totreat skin disease, to help check hemorrhages, and toprovide sedation for nervous disorders. A crystallinecompound isolated from the plant and named lagochilinehas proved to be aditerpene. Whether or not itproduces the psychoactive effects of the whole plant isunknown. There are some 34 other species of Lagochilus.Members of the mint family, labiatae, they are nativefrom central Asia to Iran and Afghanistan.

Peganum harmala,4seeds,enlargedAowerSYRIAN RUE (Peganum harmala) grows from the Mediterraneanto northern India, Mongolia, and Manchuria.Everywhere it has many uses in folk medicine. Its seedshave been employed as a spice, and its fruits are thesource of a red dye and an oil.The seeds possess known hallucinogenic alkaloids,especially harmine and harmaline. The esteem in whichthe peoples of Asia hold the plant is so extraordinarythat it might indicate a former religious use as an hallucinogen,but the purposeful use of the plant to inducevisions has not yet been established through theliterature or field work.The caltrop family, Zygophyllaceae, to which Syrianrue belongs, comprises about two dozen genera nativeto dry ports of the tropics and subtropics of bothhemispheres.43

expansumKANNA (Mesembryanthemum expansum and M. tortuosum)is the common name of two species of SouthAfrican plants. There is strong evidence \hat one or bothwere used by the Hottentots of southern Africa as visioninducingnarcotics. More than two centuries ago, it wasreported that the Hottentots chewed the root of kenna,or channa, keeping the chewed material in the mouth,with these results: "Their animal spirits were awakened,their eyes sparkled and their faces manifested laughterand gaiety. Thousands of delightsome ideas appeared,and a pleasant jollity which enabled them to be amusedby simple jests. By taking the substance to excess, theylost consciousness and fell into a terrible delirium."Since the narcotic use of these two species has notbeen observed directly, various botanists have suggested44

that the hallucinogenic kenna may actually have beencannabis or other intoxicating plants, such as severalspecies of Sclerocarya of the cashew family. These twospecies of Mesembryanthemum do have the commonname kenna, however, and they also contain alkaloidsthat have sedative, cocainelike properties capable ofproducing torpor in man.In the drier parts of South Africa, there are altogether1,000 species of Mesembryanthemum-many,like the ice plant, of bizarre form. About two dozenspecies, including the two described here, are consideredby some botanists to represent a separate genus, Sceletium.All belong to the carpetweed family, Aizoaceae,mainly South African, and are believed to be related tothe pokeweed, pink, and cactus families.45

BELLADONNA (Atropa belladonna) is well known asa highly poisonous species capable of inducing variouskinds of hallucinations. It entered into the folklore andmythology of virtually all European peoples, who fearedits deadly power. It was one of the ingredients of thetruly hallucinogenic brews and ointments concocted bythe so-called witches of medieval Europe. The attractiveshiny berries of the plant still often cause it to be accidentallyeaten, with resultant poisoning.The name belladonna ("beautiful lady" in Italian)comes from a curious custom practiced by Italianwomen of high society during medieval times. Theywould drop the sap of the plant into the eye to dilatethe pupil enormously, inducing a kind of drunken orglassy stare, considered in that period to enhancefeminine beauty and sensuality.The main active principle in belladonna is the alkaloidhyoscyamine, but the more psychoactive scopolamineis also present. Atropine has also been found, butwhether it is present in the living plant or is formedduring extraction is not clear. Belladonna is a commercialsource of atropine, an alkaloid with a wide variety ofuses in modern medicine, especially as an antisposmodic,an antisecretory, and as a mydriatic and cardiac stimulant.The alkaloids occur throughout the plant but areconcentrated especially in the leaves and roots.There are four species of Atropa distributed inEurope and from central Asia to the Himalayas. Atropabelongs to the nightshade family, Solanaceae. Belladonnais native to Europe and Asia Minor. Until the19th century, commercial collection was primarily fromwild sources, but since that time cultivation has beeninitiated in the United States, Europe, and India, whereit is an important source of medicinal drugs.46

seed,enlarged

HENBANE (Hyoscyamus niger) was often included in thewitches' brews and other toxic preparations of medievalEurope to cause visual hallucinations and the sensationof flight. An annual or biennial native to Europe, it haslong been valued in medicine as a sedative and ananodyne to induce sleep.The principal alkaloid of henbane is hyoscyamine, butthe more hallucinogenic scopolamine is also present insignificant amounts, along with several other alkaloidsin smaller concentrations.Henbane is one of 20 species of Hyoscyamus, membersof the nightshade family, Solanaceae. They arenative to Europe, northern Africa, and western andcentral Asia.Medieval witches cooking "magic" brew with toad and henbane.

Hyoscyamus nigerfruit, inpersistentcalyxfruit withcalyx removed,showing cap49

MANDRAKE (Mandragora officinarum), an hallucinogenwith a fantastic history, has long been known and fearedfor its toxicity. Its complex history as a magic hypnoticin the folklore of Europe cannot be equaled by anyspecies anywhere. Mandrake was a panacea. Its folkuses in medieval Europe were inextricably bound upwith the "Doctrine of Signatures," an old theory holdingthat the appearance of an object indicates itsspecial properties. The root of mandrake was likened tothe form of a man or woman; hence its magic. If amandrake were pulled from the earth, according tosuperstition, its unearthly shrieks could drive its collectorWoodcuts fromHortus sanitatis, 1 st editionMayence, 1485

mad. In many regions, the people claimed strongaphrodisiac properties for mandrake. The superstitioushold of this plant in Europe persisted for centuries.Mandrake, with the tropane alkaloids hyoscyamine,scopolamine, and others, was an active hallucinogenicingredient of many of the witches' brews of Europe.In fact, it was undoubtedly one of the most potentingredients in those complex preparations.Mandrake and five other species of Mandragora belongto the nightshade family, Solanaceae, and arenative to the area between the Mediterranean and theHimalayas.Mandragora officinorum51

DHATURA and DUTRA (Datura mete/) are the commonnames in India for an important Old World species ofDatura. The narcotic properties of this purple-floweredmember of the deadly nightshade family, Solanaceae,have been known and valued in India since prehistory.The plant has a long history in other countries as well.Some writers have credited it with being responsible forthe intoxicating smoke associated with the Oracle ofDelphi. Early Chinese writings report an hallucinogenthat has been identified with this species. And it is undoubtedlythe plant that Avicenna, the Arabian physician,mentioned under the name jouzmathel in the 11thcentury_. Its use as an aphrodisiac in the East Indies wasrecorded in 1578. The plant was held sacred in China,where people believed that when Buddha preached,heaven sprinkled the plant with dew.Nevertheless, the utilization of Datura preparationsin Asia entailed much less ritual than in the New World.In many parts of Asia, even today, seeds of Datura areoften mixed with food and tobacco for illicit use, especiallyby thieves for stupefying victims, who may remainseriously intoxicated for several days.Datura mete/ is commonly mixed with cannabis andsmoked in Asia to this day. leaves of a wh ite-floweredform of the plant (considered by some botanists to bea distinct species, D. fastuosa) are smoked with cannabisor tobacco in many parts of Africa and Asia.The plant contains highly toxic alkaloids, the principalone being scopolamine. Th is hallucinogen is present inheaviest concentrations in the leaves and seeds. Scopolamineis found also in the New World species of Datura(pp. 142-1 47). Datura ferox, a related Old Worldspecies, not so widespread in Asia, is also va lued forits narcotic and medicinal properties.52

Datura mete/doublefloweredformfruitDatura feroxfruit

IBOGA (Tabernanthe iboga), native to Gabon and theCongo, is the only member of the dogbane family,Apocynaceae, known to be used as an hallucinogen.The plant is of growing importance, providing thestrongest single force against the spread of Christianityand Islam in th is region.The yellowish root of the iboga plant is employedin the initiation rites of a number of secret societies,the most famous being the Bwiti cult. Entrance into thecult is conditional on having "seen" the god plant Bwiti,which is accomplished through the use of iboga.The drug, discovered by Europeans toward the middleof the last century, has a reputation as a powerfulstimulant and aphrodisiac. Hunters use it to keep themselvesawake all night. large doses induce unworldlyvisions, and "sorcerers" often take the drug to seek informationfrom ancestors and the spirit world.Ibogaine is the principal indole alkaloid among a dozenothers found in iboga.The pharmacology of ibogaineis well known. Inaddition to being an hallucinogen,ibogaine inlarge doses is a strongcentral nervous systemstimulant, leading to convulsions,paralysis, andarrest of respiration."Payment of the Ancestors,"taking place between two shrubbybushes of Tabernanthe iboga inthe Fang Cult of Bwiti, Congo.(Photo by J. W. Fernandez.)

Tabernantheibogaflower,enlarged55

NEW WORL D HALLUCINOGENSIn the New World-North, Central, and South Americaand the West Indies-the number and cultural importanceof hallucinogens reached amazing heights inthe past-and in places their role is undiminished.More than ninety species are employed for theirintoxicating principles, compared to fewer than a dozenin the Old World. It would not be an exaggeration tosay that some of the New World cultures, particularlyin Mexico and South America, were practically enslavedby the religious use of hallucinogens, which acquireda deep and controlling significance in almostevery aspect of life. Cultures in North America andthe West Indies used fewer hallucinogens, and theirrole often seemed secondary. Although tobacco andcoca, the source of cocaine, have become of worldwideimportance, none of the true hallucinogens ofthe Western Hemisphere has assumed the global significanceof the Old World cannabis.No ethnological study of American Indians can beconsidered complete without an in-depth appreciationof their hallucinogens. Unexpected discoveries havecome from studying the hallucinogenic use of NewWorld plants. Many hallucinogenic preparations calledfor the addition of plant additives capable of altering theintoxication. The accomplishments of aboriginal Americansin the use of mixtures have been extraordinary.While known New World hallucinogens are numerous,studies are still uncovering species new to the list. Themost curious aspect of the studies, however, is why, inview of their vital importance to New World cultures,the botanical identities of many of the hallucinogensremained unknown until comparatively recent times.56

PUFFBALLS (Lycoperdon mixtecorum and L. marginatum)are used by the Mixtec Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico, asauditory hallucinogens. After eating these fungi, anative hears voices and echoes. There is apparently noceremony connected with puffballs, and they do not enjoythe place as divinatory agents that the mushroomsdo in Oaxaca. L. mixtecorum ls the stronger of the two.It is called gi-i-wa, meaning "fungus of the first quality. "L. marginatum, which has a strong odor of excrement,is known as gi-i-sa-wa, meaning ''fungus of the secondquality. "J.Although intoxicating substances have not yet beenfound in the puffballs, there are reports in the literaturethat some of them have had narcotic effects wheneaten. Most of the estimated 50 to 1 00 species ofLycoperdon grow in mossy forests of the temperatezone. They belong to the Lycoperdaceae, a family ofthe Gasteromycetes.57

The use of hallucinogenic mushrooms, which dates back several thousandyears, centers in the mountains of southern Mexico.MUSHROOMS of many species were used as hallucinogensby the Aztec Indians, who called themteonanacatl, meaning "flesh of the gods" in theNahuatl Indian language. These mushrooms, all of thefamily Agaricaceae, are still valued in Mexican magicoreligiousrites. They belong to four genera: Conocybeand Panaeo/us, almost cosmopolitan in their range;Psilocybe, found in North and South America, Europe,and Asia; and Stropharia, known in North America, theWest Indies, and Europe.58

MUSHROOM WORSHIP seems to have roots in centuriesof native tradition . Mexican frescoes, going backto A. D. 300, have designs suggestive of mushrooms.Even more remarkable are the artifacts called mushroomstones (p. 60 ), excavated in large numbers fromhighland Maya sites in Guatemala and dating back to1000 B.C. Consisting of a stem with a human or animalface and surmounted by an umbrella-shaped top, theylong puzzled archaeologists. Now interpreted as a kind oficon connected with re ligious rituals, they indicate that3,000 years ago, a sophisticated religion surroundedthe sacramental use of these fungi.It has been suggested that perhaps mushrooms werethe earliest hallucinogenic plants to be discovered. Theother-worldly experience induced by these mysteriousforms of plant life could easily have suggested a spiritualplane of existence .Detail from a fresco otTepontitlo (Teotihuocan,Mexico) representingTloloc, the god of clouds,ra in, and waters. Notethe pole bluemushrooms with orangestems and also the"colorines"-the darkerblue, bean-shaped formswith red spots. See pages96 and 97 fo r discussion ofco lorines and pi ule.(After Heim and Wasson.)59

MUSHROOM STONESTypical icons probably associated with mushroom cults dating back3,000 years in Guatemala.60

EARLY USE OF THE SACRED MUSHROOMS is knownmainly from the extensive descriptions written by theSpanish clerics. For this we owe them a great debt.One chronicler, writing in the mid-1500 's, after theconquest of Mexico, referred frequently to those mushrooms"which are harmful and intoxicate like wine,"so that those who eat them "see visions, feel a faintnessof heart and are provoked to lust''; the natives"when they begin to get excited by them start dancing,singing, weeping. Some do not want to eat butsit down . . . and see themselves dying in a vision;others see themselves being eaten by a wild beast;others imagine that they are capturing prisoners of war,that they are rich, that they possess many slaves, thatthey had committed adultery and were to have theirheads crushed for the offense.A work of Aztec medicine mentions three kinds ofintoxicating mushrooms. One, teyhuintli, causes "madnessthat on occasion is lasting, of which the symptomis an uncontrollable laughter; there are others which. . . bring before the eyes all sorts of things, such aswars and the likeness of demons. Yet others are notless desired by princes for their festivals and banquets,and these fetch a high price. With night-long vigils arethey sought, awesome and terrifying."Detail from fresco ot Socuala, Teotihuacan, Mexico, showing fourgreenish ''mushrooms" that seem to be emerging from the mouth ofa god, possibly the Sun God., --61

SPANISH OPPOSITION to the Aztecs ' worship of pagande ities with the sacramental aid of mushrooms wasstrong. Although the Spanish conquerors of Mexicohated and attacked the religious use of all hallucinogens-peyote, ololiuqui, toloache, and others-teonanacat lwas the target of special wrath. Their religious fanaticismwas drawn especially toward this despised andfeared form of plant life that, through its vision-givingpowers, held the Indian in awe, allowing him to communedirect ly with his gods. The new religion, Christianity,had nothing so attractive to offer him. Trying tostamp out the use of the mushrooms, the Spaniardssucceeded only in driving the custom into the hinterlands,where it persists today. Not on ly did it persist,but the ritual adopted many Christian aspects, and themodern ritual is a pagan-Christian blend.The pa gan gad of the underworld speak s through the mushroom,teonanocatl, as represented by a Mexican artist in the 16th century.(From the Magliabecchiano Codex, Bibl ioteca Nazionale, Florence.)62

A 16th-century illustration of teonanacatl (a), the intoxicating mushroomof the Aztecs, still valued in Mexican magico-religious rites; identityof (b) is unknown. From Sahagun's Historic general de las cosas deNueva Espana, Vol. IV (Florentine Codex).IDENTIFICATION OF THE SACRED MUSHROOMS wasslow in coming. Driven into hiding by the Spaniards,the mushroom cult was not encountered in Mexico forfour centuries. During that time, although the Mexicanflora was known to include various toxic mushrooms, itwas believed that the Aztecs had tried to protect theirreal sacred plant: they had led the Spaniards to believethat teonanacatl meant mushroom, when it actuallymeant peyote. It was pointed out that the symptomsof mushroom intoxication coincided remarkably withthose described for peyote intoxication and that driedmushrooms might easily have been confused with theshriveled brown heads of the peyote cactus. But thenumerous detailed references by careful writers, includingmedical men trained in botany, argued againstthis theory.Not until the 1930's were botanists able to identifyspecimens of mushrooms found in actual use in divinotoryrites in Mexico. later work has shown that morethan 20 species of mushrooms are similarly employedamong seven or eight tribes in southern Mexico.63

THE MODERN MUSHROOM CEREMONY of the MazeteeIndians of northeastern Oaxaca illustrates the importanceof the ritual in present-day Mexico and howthe sacred character of these plants has persisted frompre-conquest times. The divine mushrooms are gatheredduring the new moon on the hillsides before dawn bya virgin; they are often consecrated on the altar of thelocal Catholic church. Their strange growth pattern helpsmake mushrooms mysterious and awesome to the Mazetee,who call them 'nti-si-tho, meaning "worshipful objectthat springs forth." They believe that the mushroomsprings up miraculously and that it may be sent fromouter realms on thunderbolts. As one Indian put itpoetically: "The little mushroom comes of itself, no oneknows whence, like the wind that comes we know notwhen or why. "The all-night Mazatec ceremony, led usually by awoman shaman (curandera), comprises long, complicated,and curiously repetitious chants, percussive beats, andCurandera with Mazatec patient and dish af sacred mushrooms.Scene is typical of the all-night mushroom ceremony. Curandera isunder the influence of the mushrooms.64

prayers. Often a curing rite takes place during whichthe practitioner, through the "power" of the sacredmushrooms, communicates and intercedes with supernaturalforces. There is no question of the vibrantrelevance of the mushroom rituals to modern Indianlife in southern Mexico. None of the attraction ofthese divine mushrooms has been lost as a result ofcontact with Christianity or modern ideas. The spirit ofreverence characteristic of the mushroom ceremony is asprofound as that of any of the world's great religions.KINDS OF MUSHROOMS USED by different shamansare determined partly by personal preference and partlyby the purpose of the use. Seasonal and regionalavailability also have a bearing on the choice. Strophariacubensis and Psilocybe mexicana may be the most commonlyemployed, but half a dozen other species ofPsilocybe as well as Conocybe siliginoides and Panaeo/ussphinctrinus are also important. The native names arecolorful and sometimes significant. Psi/ocybe aztecorumis called "children of the waters"; P. zapotecorum,"crown-of-thorns mushroom"; and P. caerulescensvar. nigripes, "mushroom of superior reason." (See illustrationson pp. 66-67). The possibility exists thatother hallucinogenic species of mushrooms are also used.It is possible, too, that Psilocybe species are used asinebriants outside of Mexico. P. yungensis has beensuggested as the mysterious "tree mushroom" that earlyJesuit missionaries reported as being employed by theYurimagua Indians of Amazonian Peru as the source ofa potent intoxicating beverage. This species is known tocontain an hallucinogenic principle. Field work in moderntimes, however, has not disclosed the narcotic use ofany mushrooms in the Amazon area .65

THE EFFECTS OF THE MUSHROOMS include muscularrelaxation or limpness, pupil enlargement, hilarity,and difficulty in concentration. The mushrooms causeboth visual and auditory hallucinations. Visions arebreathtakingly lifelike, in color, and in constant motion.They are followed by lassitude, mental and physicaldepression, and alteration of time and space perception.The user seems to be isolated from the worldaround him; without loss of consciousness, he becomeswholly indifferent to his surroundings, and his dreamlikestate becomes reality to him. This peculiarity ofthe intoxication makes it interesting to psychiatrists.One investigator who ate mushrooms in a MexicanIndian ceremony wrote that "your body lies in thedarkness, heavy as lead, but your spirit seems to soar. . . and with the speed of thought to travel where itlisteth, in time and space, accompanied by the shaman'ssinging . . . What you are seeing and . . . hearingappear as one; the music assumes harmonious shapes,giving visual form to its harmonies, and what you areseeing takes on the modalities of music-the music ofthe spheres."All your senses are similarly affected; the cigarette. . . smells as no cigarette before had ever smelled;the glass of simple water is infinitely better than champagne. . . the bemushroomed person is poised inspace, a disembodied eye, invisible, incorporeal, seeingbut not seen . . . he is the five senses disembodied . . .your soul is free, loses all sense of time, alert as itnever was before, living an eternity in a night, seeinginfinity in a grain of sand . . . [The visions may be of]almost anything . . . except the scenes of your everydaylife." As with other hallucinogens, the effects ofthe mushrooms may vary with mood and setting.68

A scientist's description of his experience after eating32 dried specimens of Psilocybe mexicana was as follows:" . . . When the doctor supervising the experimentbent over me . . . he was transformed into an Aztecpriest, and I would not have been astonished if he haddrawn an obsidian knife . . . it amused me to see howthe Germanic face . . . had acquired a purely Indianexpression. At the peak of the intoxication . . . therush of interior pictures, mostly abstract motifs rapidlychanging in shape and color, reached such an alarmingdegree that I feared that I would be torn into thiswhirlpool of form and color and would dissolve. Afterabout six hours, the dream came to an end . . . I feltmy return to everyday reality to be a happy returnfrom a strange, fantastic but quite really experiencedworld into an old and familiar home. "69

CHEMICAL CONSTITUTION of the hallucinogenic mushroomshas surprised scientists. A wh ite crystallinetryptamine of unusual structure-an acidic phosphoricacid ester of 4-hydroxydimethyltryptamine-was isolated.This indole derivative, named psilocybin, is anew type of structure, a 4-substituted tryptamine witha phosphoric acid radical, a type never before knownas a naturally occurring constituent of plant tissue.Some of the mushrooms also contain minute amountsof another indolic compound-psilocin-which is unstable.While psilocybin has been found also in Europeanand North American mushrooms, apparently onlyin Mexico. and Guatemala have psilocybin-containingmushrooms been purposefully used for ceremonial intoxication.HbIo= P - o - +I IIPsilocin is believed by somebiochemists to be the precursorHof the more stable psilocybin.IH-C-HHH /N -T -H0 H-C -H H'H-C - HIHPsilocybinHI0HIH-C-HIN-C-H/ IH- C-H H"H-C-HIHPsilocin70

A laboratory culture of Psilocybe mexicana, grown from spores,an innovation that speeded analysis of the ephemeral mushroom.(After Heim & Wasson: Les Champignons Hallucinogimes du Mexique)CHEMICAL INVESTIGATION of the Mexican mushroomswas difficult until they could be cultivated. They arealmost wholly water and great quantities of them areneeded for chemical analyses because their chemicalconstitution is so ephemeral. The clarification of thechemistry of the Mexican mushrooms was possible onlybecause mycologists were able to cultivate the plantsin numbers sufficient to satisfy the needs of the chemists.This accomplishment represents a phase in the studyof hallucinogenic plants that must be imitated in theinvestigation of the chemistry of other narcotics. Thelaboratory, in this case, became an efficient substitutefor nature. By providing suitable conditions, scientistshave learned to grow many species in artificial culture.Cultivation of edible mushrooms is an importantcommercial enterprise and was practiced in France earlyin the seventeenth century. Cultivation for laboratorystudies is a more recent development.71

fruit ( 1 in.in diameter)RAPE DOS INDIOS (Maquira sclerophylla;known also as 0/medioperebeasclerophylla) is an enormoustree of the fig family, Moraceae.In the Parlana region of the centralAmazon in Brazil, the Indiansformerly prepared an hallucinogenicsnuff from the dried fruits.The snuff was taken in tribal ceremonials,but encroaching civilizationhas obliterated its use.Further studies of this narcoticare needed. The preliminary chemicalinvestigations made so farhave not indicated what the activeprinciple may be.

SWEET FLAG (Acorus calamus), also called sweetcalomel, grows in damp places in the north and southtemperate regions. A member of the arum family,Araceae, it is one of two species of Acorus. There issome indirect evidence that Indians of northern Canada,who employ the plant as a medicine and a stimulant,may chew the rootstock as an hallucinogen. In excessivedoses, it is known to induce strong visual hallucinations.The intoxicating properties may be due to a-asaroneand /3-asarone, but the chemistry and pharmacology ofthe plant are still poorly understood.

Colombian Indians using a snuffing tube fa shioned from bird bone.VIROLAS (Virola calophy/la, V. calophylloidea, and V.theiodora) are among the most recently discovered hallucinogenicplants. These jungle trees of medium sizehave glossy, dark green leaves with clusters of tinyyellow flowers that emit a pungent aroma. The intoxicatingprinciples are in the blood-red resin yielded bythe tree bark, which makes a powerful snuff.Virola trees are native to the New World tropics.They are members of the nutmeg family, Myristicaceae,which comprises some 300 species of trees in 1 8 genera.The best known member of the family is Myristica fragrans,an Asiatic tree that is the source of nutmegand mace.In Colombia, the species most often used for hallucinogenicpurposes are Virola calophylla and V. calophy/loidea,whereas in Brazil and Venezuela the Indiansprefer V. theiodora, which seems to yield a morepotent resin.74

flower cluster,enlarged75

Strip of bark fromVirola tree, showingoozing red resin.AN INTOXICATING SNUFF isprepared from the bark of Virolatrees by Indians of the northwesternAmazon and the headwatersof the Orinoco. An anthropologistwho observed the YekwanaIndians of Venezuela in their preparationand use of the snuff in 1909commented:"Of special interest are cures,during which the witch doctor inhaleshakudufha. This is a magicalsnuff used exclusively by witchdoctors and prepored from thebark of a certain tree which,pounded up, is bailed in a smallearthenware pot, until all the waterhas evaporated and a sedimentremains at the bottom of the pot."This sediment is toasted in thepot over a slight flre and is thenfinely powdered with the blade ofa knife. Then the sorcerer blows alittle of the powder through areed . . . into the air. Next, hesnuffs, whilst, with the same reed,he absorbs the powder into eachnostril successively.''The hakudufha obviously hasa strong stimulating effect, forimmediately the witch doctor beginsto sing and yell wildly, all thewhile pitching the upper port ofhis body backwards and forwards."

Among numerous tribes in eastern Colombia, theuse of Virola snuff, often called yakee or parica, isrestricted to shamans. Among the Waik6 or Yanonamotribes of the frontier region of Brazil and Venezuela,epena or nyakwana, as the snuff is called, is not restrictedto medicine men, but may be snuffed ceremoniallyby all adult males or even taken occasionallywithout any ritual basis by men individually. The medicinemen of these tribes take the snuff to induce atrance that is believed to aid them in diagnosing andtreating illness.Although the use of the snuff among the Indians ofSouth America had been described earlier, its sourcewas not definitely identified as the Virola tree until 1954.Waiko Indian scraping Virolaresin into pot, preparatory tocooking it.77

PREPARATION OF VIROLA SNUFF varies among differentIndians. Some scrape the soft inner layer of thebark and dry the shavings gently over a flre. The shavingsare stored for later use. When the snuff is needed,the shavings are pulverized by pounding with a pestlein a mortar made from the fruit case of the Brazil-nuttree. The resulting powder is sifted to a flne, pungentbrown dust. To this may be added the powdered leavesof a small, sweet-scented weed, Justicia, and the ashesof amasita, the bark of a beautiful tree, Elizabethaprinceps. The snuff is then ready for use.Other Indians fell the tree, strip off and gently heatthe bark, collect the resin in an earthenware pot, bailDried Justicia leaves ore groundbefore being added to snuff.78

it down to a thick paste, sun-dry the paste, crush itwith a stone, and sift it. Ashes of several barks andthe leaf powder of Justicia may or may not be added.Still other Indians knead the inner shavings offreshly stripped bark to squeeze out all the resin andthen bail down the resin to get a thick paste that issun-dried and prepared into snuff with ashes added .The same resin, applied directly to arrowheads andcongealed in smoke, is one of the Waika arrow poisons.When supplies of snuff are used up in ceremonies, theIndians often scrape the hardened resin from arrowtips to use it as a substitute. It seems to be as potentas the snuff itself.Woika Indian sifting groundJusticio leaves to make fine powderfor additive to Virolo snuff.79

A SNUFF-TAKING CEREMONY is conducted annuallyby many Waika tribes to memorialize those who havedied the previous year. Endocannibalism comprises partof the rite; the ashes of calcined banes of the departedare mixed into a fermented banana drink and areswallowed with the beverage.The ceremony takes place in a large round house.Following initial chanting by a master of ceremony, themen and older bays form groups and blow huge amountsof snuff through long tubes into each other's nostrils(p. 74). They then begin to dance and to run wildly,shouting, brandishing weapons, and making gestures ofbravado. Pairs or groups engage in a strange ritual inwhich one participant thrusts out his chest and is poundedforcefully with fists, clubs, or rocks by a companion,who then offers his own chest for reciprocation. Althoughthis punishment, in retribution for real or imaginedgrievances, often draws blood, the effects of the narcoticare so strong that the men do not flinch or showsigns of pain. The opponents then squat, throw theirarms about each other,and shout into one another'sears. All begin hoppingand crawling across thefloor in imitation of animals.Eventually all succumbto the drug, losingconsciousness for up tohalf on hour. Hallucinationsore said to be experiencedduring this time.Waika round house inclearing in Amazon forest.

EFFECTS OF VIROLA SNUFF are felt within minutesfrom the time of initial use. First there is a feeling ofincreasing excitability. This is followed by a numbnessof the limbs, a twitching of the face, a lack of muscularcoordination, nasal discharges, nausea, and, frequently,vomiting . Macropsia-the sensation of seeing thingsgreatly enlarged-is characteristic and enters into Waik6beliefs about hekulas, the spirit forces dwelling in theVirola tree and controlling the affairs of man. Duringthe intoxication, medicine men often wildly gesticulate,fighting these gigantic hekulas.CAUSE OF THE NARCOTIC EFFECT of Virola has beenshown by recent studies to be an exceptionally high concentrationof tryptamine alkaloids in the resin. Waik6snuff prepared exclusively from the resin of Virolatheiodora has up to 8 percent of tryptamines, mainlythe highly active 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine.Two new alkaloids of a different type-,8-carbolineshavealso been found in the resin; they act as monoamineoxidase inhibitors and make it possible for the tryptaminesto take effect when the resin is taken orally.OTHER WAYS OF TAKING VIROLA RESIN besidessnuffing it are sometimes employed. The primitive nomadicMaku of Colombia often merely scrape resin from thebark of the tree and lick it in crude form. The Witoto,Bora, and Muinane of Colombia prepare little pelletsfrom the resin, and these are eaten when, to practicewitchcraft or diagnose disease, the medicine men wishto "talk with the spirit people"; the intoxication beginsfive minutes after ingestion. There is .some vague evidencethat certain Venezuelan natives may smoke thebark to get the intoxicating effects.81

USE OF VIROLA AS AN ARROW POISON by theWaika Indians is one of the recent discoveries in thestudy of curare. The red resin from the bark of Virolatheiodora is smeared on an arrow or dart, which isthen gently heated in the smoke of a flre (shown inthe illustration below) to harden the resin. The killingaction of the poison is slow. The chemical constituentof the resin responsible for this action is still unknown.It is interesting that although the arrows are tippedwhile the hal lucinogenic snuff is being prepared fromresin from the same tree, the two operations are carriedout by different medicine men of the same tribe.Many other plants are employed in South America inpreparing arrow poisons, most of them members of thefamilies Loganiaceae and Menispermaceae.Waik6 Indian holding poisondarts in smoky fire to congealVirola resin, applied by dippingor spreading with fingers.82

floweringbranchJusticiapectoralisvar.stenophyllaMASHA-HARI (Justicia pectoralis var. stenophylla) is asmall herb cultivated by the Waika Indians of theBrazilian-Venezuelan frontier region. The ciromatic leavesare occasionally dried, powdered, and mixed with thehallucinogenic snuff made from resin of the Virola tree.Other species of Justicia have been reported to be employedin that region as the sole source of a narcoticsnuff.Hallucinogenic constituents have not yet been foundin Justicia, but if any species of the genus is utilized asthe only ingredient of an intoxicating snuff, then one ormore active constituents must be present. The 300species of Justicia, members of the acanthus family,Acanthaceae, grow in the tropics and subtropics of bothhemispheres.83

JUREMA (Mimosa hostilis) is a poorly understood shrub,the roots of which provide the "miraculous jurema drink, "known in eastern Brazil as ajuco or vinho de juremo.Other species of Mimosa ore also locally called jurema.Several tribes in Pernambuco-the Kariri·, Pankaruru,Tusha, and Fulnio-consume the beverage in ceremonies.Usually connected with warfare, the hallucinogen wasused by now extinct tribes of the area to • 'pass thenight navigating through the depths of slumber" justprior to sallying forth to war. They would see "gloriousvisions of the spirit land . . . (or) catch a glimpse ofthe clashing rocks that destroy souls of the dead journeyingto their gool or see the Thunderbird shootinglightning from a huge tuft on his head and producingclaps of thunder . . ." It appears, however, that thehallucinogenic use of M. hostilis has nearly disappearedin recent times.Little is known about the hallucinogenic properties ofthis plant, which was discovered more than 150 yearsago. Early chemical studies indicated an active alkaloidgiven the name nigerine but later shown to beidentical with N, N-dimethyltryptamine. Since the tryptaminesare not active when taken orally unless in thepresence of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, it is obviousthat the jurema drink must contain ingredients other thanM. hostilis or that the plant itself must contain an inhibitorin its tissues.The genus Mimosa, closely allied to Acacia andAnadenanthera, comprises some 500 species of tropicaland subtropical herbs and small shrubs. The mimosasbelong to the subfamily Mimosoideae of the bean family,Leguminosae. Most of them are American, although someoccur in Africa and Asia. Jurema is native only to thedry regions of eastern Brazil.84

Mimosahostilissingle flower,enlarged

AnadenantheraYOPO or PARICA (Anadenanthera peregrina or Piptadeniaperegrina) is a South American tree of the beanfamily, Leguminosae. A potent hallucinogenic snuff isprepared from the seeds of this tree. The snuff, nowused mainly in the Orinoco basin, was first reportedfrom Hispaniola in 1496, where the Taina Indians calledit cohoba. Its use, which has died out in the West Indies,was undoubtedly introduced to the Caribbean area byIndian invaders from South America.The hallucinogenic principles found in A. peregrinaseeds include N, N-dimethyltryptamine, N-monomethyltryptamine,5-methoxydimethyltryptamine, and severalrelated bases. Bufotenine, also present in A. peregrinaseeds, apporently is not hallucinogenic. Elucidation ofthe chemicol make-up of the seeds of the yopo tree hasonly recently been accomplished. Future studies mayincrease our knowledge of the active principle of theseseeds.86

THE PRE PARATION OF YOPO SNUFF varies somewhatfrom tribe to tribe. The pods, which are borne profuselyon the yopo tree, are Aat and deeply constrictedbetween each seed. Gray-black when ripe,the seed pods break open, exposing from three toabout ten Aat seeds, or beans. These are gatheredduring January and February, usually in large quantitiesand often ceremonially. They are first slightly moistenedand rolled into a paste, which is then roasted gentlyover a slow fire until it is dried out and toasted. Sometimesthe beans are allowed to ferment before beingrolled into a paste. After the toasting, the hardenedpaste may be stored for later use. Some Indians toastthe beans and crush them without molding them intoa paste, grinding them usually on an ornate slab ofhardwood made especially for the purpose.Several early explorers described the process.In 1 801 Alexander von Humboldt, the German naturalist87

and explorer, detailed the preparation of yopo by theMaipures of the Orinoco. In 1851, Richard Spruce, anEnglish explorer, visited the Guahibos, another tribe ofthe Orinoco, and wrote: "In preparing the snuff, theroasted seeds of niopo are placed in a shallow woodenplatter that is held on the knee by means of a broodhandle grasped firmly with the left hand; then crushedby a small pestle of the hard wood of pao d'arco . . .which is held between the fingers and thumb of theright hand."The resulting grayish-green powder is almost alwaysmixed with about equal amounts of some alkaline substance,which may be lime from snail shells or theashes of plant material. Apparently, the ashes are madefrom a great variety of plant materials: the burned fruitof the monkey pot, the bork of many different vinesand trees, and even the roots of sedges. The additionof the ashes probably serves a merely mechanical purpose:to keep the snuff from caking in the humid climate.The addition of lime or ashes to narcotic or stimulantpreparations is a very widespread custom in bothhemispheres. They are often added to betel chew,pituri, tobacco, epena snuff, coca, etc. In the case ofyopo snuff, the alkaline admixture seems not to be essential.Some Indians, such as the Guahibos, may occasionallytake the powder alone. The explorer Alexandervon Humboldt, who encountered the use of yopoin the Orinoco 175 years ago, mistakenly stated that". . . it is not to be believed that the niopo acaciapods are the chief cause of the stimulating effects ofthe snuff . . . The effects are due to freshly calcinedlime." In his time, of course, the presence of activetryptamines in the beans was unknown.88

snuffing tubewith shaftof reed anda palm fruitnosepiecebifurcatedbird-banesnuffing tubewith palmfruit nosepiecesthreehardwoodpestlesor crushersandhardwoodmortar troyfor grindi.ngyapo seedsSnuffing Paraphernalia89

A yopo tree (Anodenanthera peregrina) in Amazonian Brazil. Theseeds of this tree are the source of a potent hallucinogenic snuff.Yopo snuff is inhaled through hollow bird-bone orbamboo tubes. The effects begin almost immediately:a twitching of the muscles, slight convulsions, and lackof muscular coordination, followed by nausea, visualhallucinations, and disturbed sleep. An abnormalexaggeration of the size of objects (macropsia) iscommon. In an early description, the Indians say thattheir houses seem to '' ... be turned upside down andthat men are walking on their feet in the air. "90

South American Indians of the upper Orinoco region in characteristicgesticulating postures while under the influence of yopo snuff.91

VI LCA and SEBIL are snuffs believed to have beenprepared in the past from the beans of Anadenantheracolubrina and its variety cebi/ in central and southernSouth America, where A. peregrina does not occur. A.colubrina seeds are known to possess the same hallucinogenicprinciples as A. peregrina (see p. 86 ).An early Peruvian report, dated about 1571 , statesthat Inca medicine men foretold the future by communicatingwith the devil through the use of vilca, orhuilca. In Argentina, the early Spaniards found theComechinIndians taking seb il "through the nose" tobecome intoxicated, and in another tribe the sameplant was chewed for endurance . Since these Indiancultures have disappeared, our knowledge of vilcasnuffs and their use is limited.Ancient Snuffing Instruments92wooden mortarand pestlewith incisedabstractdesigns;Boliv iasnuff tray withbi rd-head designs;Bolivia

GE N ISTA (Cytisus canariensis) is employed as an hallucinogenin the magic practices of Yaqui medicine menin northern Mexico. Native to the Canary Islands, theplant was introduced into Mexico. Rarely does anynonindigenous plant find its way into the religious andmagic customs of a people. Known also by the scientificnome Genista canariensis, this species is the "genista"of florists.Plants of the genus Cytisus ore rich in cytisine, onalkaloid of the lupine group. The alkaloid has neverbeen pharmacologically demonstrated to hove hallucinogenicactivity, but it is known to be toxic and to causenausea, convulsions, and death through failure ofrespiration.About 80 species of Cytisus, belonging to the beanfamily, Leguminosae, ore known in the Atlantic islands,Europe, and the Mediterranean area. Some speciesare highly ornamental; some ore poisonous.93

MESCAL BEAN (Sophora secundiflora), also called redbean or coralillo, is a shrub or small tree with silverypods containing up to six or seven red beans or seeds.Before the peyote religion spread north of the RioGrande, at least 12 tribes of Indians in northern Mexico,New Mexico, and Texas practiced the vision-seekingRed Bean Dance centered around the ingestion of adrink prepared from these seeds. Known also as theWichita, Deer, or Whistle Dance, the ceremony utilizedthe beans as an oracular, divinatory, and hallucinogenicmedium.Because the red bean drink was highly toxic, oftenresulting in death from overdoses, the arrival ofa more spectacular and safer haflucinogen in the formof the peyote cactus (see p. 114) led the natives toabandon the Red Bean Dance. Sacred elements do notoften disappear completely from a culture; today theseeds are used as an adornment on the uniform ofthe leader of the peyote ceremony.An early Spanish explorer mentioned mescal beansas an article of trade in Texas in 1539. Mescal beanshave been found at sites dating before A.D. 1000,with one site dating back to 1500 B.C. Archaeologicalevidence thus points to the existence of a prehistoriccult or ceremony that used the red beans.The alkaloid cytisine is present in the beans. Itcauses nausea, convulsions, and death from asphyxiationthrough its depressive action on the diaphragm.The mescal bean is a member of the bean family,Leguminosae. Sophora comprises about 50 speciesthat are native to tropical and warm parts of bothhemispheres. One species, S. japonica, is medicinallyimportant as a good source of rutin, used in modernmedicine for treating capillary fragility.94

Sophora secundiflorafloweringbronchfruit{woody pod)seedceremonial necklace{Kiowa tribe, Anadarko, Oklahoma)95

COLORINES (several species of Erythrina) may be usedas hallucinogens in some parts of Mexico. The brightred beans of these plants resemble mescal beans(see p. 94), long used as a narcotic in northern Mexicoand in the American Southwest. Both beans are sometimessold mixed together in herb markets, and themescal bean plant is sometimes called by the same commonname, colorin.Some species of Erythrina contain alkaloids of theisoquinoline type, which elicit activity resembling thatof curare or arrow poisons, but no alkaloids knownto possess hallucinogenic properties have yet beenfound in these seeds.Some 50 species of Erythrina, members of the beanfamily, leguminosae, grow in the tropics and subtropicsof both hemispheres.Erythrinaamericana

Rhynchosiaphaseoloidesfruitingbranchseeds,enlargedPIULE (several species of Rhynchosia) have beautifulred and black seeds that may have been valued as anarcotic by ancient Mexicans. What appear to be theseseeds have been pictured, together with mushrooms,falling from the hand of the Aztec rain god in theTepantitla fresco of A.D. 300-400 ( see p. 59), suggestinghallucinogenic use . Modern Indians in southernMexico refer to them as piule, one of the names alsoapplied to the hallucinogenic morning-glory seeds.Seeds of some species of Rhynchosia have givenpositive alkaloid tests, but the toxic principles havestill not been characterized .Some 300 species of Rhynchosia, belonging to thebean family, Leguminosae, are known from the tropicsand subtropics. The seeds of some species are importantin folk medicine in several countries.97

A Y AHUASCA and CAAPI are twoof many local names for either oftwo species of a South Americanvine: Banisteriopsis caapi or 8.inebrians. Both are gigantic junglelianas with tiny pink flowers. Likethe approximately 1 00 other speciesin the genus, their botany is poorlyunderstood. They belong to thefamily Malpighiaceae.An hallucinogenic drink made fromthe bark of these vines is widelyused by Indians in the western Amazon-Brazil,Colombia, Peru, Ecuador,and Bolivia. Other local namesfor the vines or the drink madefrom them are dopa, natema, pinde,and yaje. The drink is intenselybitter and nauseating.In Peru and Ecuador, the drinkis made by rasping the bark andboiling it. In Colombia and Brazil,the scraped bark is squeezed incold water to make the drink. Sometribes add other plants to alteror to increase the potency of thedrink. In some ports of the Orinoco,the bark is simply chewed. Recentevidence suggests that in thenorthwestern Amazon the plantsmay be used in the form of snuff.Ayahuasca is popular for its "telepathicproperties," for which, ofcourse, there is no scientific bosis.

Banisteriopsiscaapi99

EARLIEST PUBLISHED REPORTS of ayahuasca date from1858 but in 1851 Richard Spruce, an English explorer,had discovered the plant from which the intoxicatingdrink was made and described it as a newspecies. Spruce also reported that the Guahibos alongthe Orinoco River in Venezuela chewed the dried stemfor its effects instead of preparing a drink from the bark.Spruce collected flowering material and also stems forchemical study. Interestingly, these stems were notanalyzed until 1969, but even after more than a century,they gave results (p. 1 03) indicating the presenceof alkaloids.In the years since Spruce's discovery, many explorersand travelers who passed through the western Amazonregion wrote about the drug. It is widely known in theAmazon but the whole story of this plant is yet to beunraveled. Some writers have even confused ayahuascawith completely different narcotic plants.Colorado Indian from Ecuador rasping the bark of Banisteriopsisastep in preparation of the narcotic ayohuasca drink.100

two examples ofpottery vesselsused inoyohuascaceremonyThe ceremonial vessel used in the ayahuasca ritual is always hungby the Indians under the eaves at the right side of a house. Althoughoccasionally redecorated, it is never woshed.EFFECTS of drinking ayahuasca range from a pleasantintoxication with no hangover to violent reactions withsickening after-effects. Usually there are visual hallucinationsin color. In excessive doses, the drug brings onnightmarish visions and a feeling of reckless abandon.Consciousness is usually not lost, nor is there impairmentof the use of the limbs. In fact, dancing is a major partof the ayahuasca ceremony in some tribes. The intoxicationends with a deep sleep and dreams.An ayahuasca intoxication is difficult to describe.The effect of the active principles varies from person toperson. In addition, preparation of the drink variesfrom one region to another, and various plant additivesmay also alter the effects.101

The Yuruparf ceremony in the Colombian Amazon involves ritualayahuasca intoxication. The Indians are blowing sacred bark flutes.CEREMONIAL USES of ayahuasca are of major importancein the lives of South American Indians. In easternPeru, medicine men take the drug to diagnose and treatdiseases. In Colombia and Brazil, the drug is employedin deeply religious ceremonies that are roated in tribalmythology. In the famous Yurupari ceremony of theTukanoan Indians of Amazonian Colombia-a ceremonythat initiates adolescent boys into manhood-the drugis given to fortify those who must undergo the severelypainful ordeal that forms a part of the rite.The intoxication of ayahuasca or caapi among theseIndians is thought to represent a return to the originof all things: the user "sees" tribal gods and thecreation of the universe and of man and the animals.This experience convinces the Indians of the reality oftheir religious beliefs, because they have "seen" everythingthat underlies them. To them, everyday life isunreal, and what caapi brings them is the true reality.102

CHEMICAL STUDIES of the two ayahuasca vines havesuffered from the botanical confusion surrounding them.However, it appears that both species owe their hallucinogenicactivity primarily to harmine, the · major,8-carboline alkaloid in the plants. Harmaline andtetrahydroharmine, alkaloids present in minor amounts,may also contribute to the intoxication. Early chemicalstudies isolated these several alkaloids but did notrecognize their identity. They were given names as "new"alkaloids. One of these names-telepathine- is anindication of the widespread belief that the drink preparedfrom these vines gave the Indian medicine mentelepathic powers.HarmineNCH3 0 HarmalineCH3CH,ON HCH3TetrahydroharmineChemical formulas of Bonisteriopsis caapi and 8. inebrians alkaloids.Indole nucleus is shown in red.103